Dietary risk factors, such as low fruit and vegetable intake and high sodium intake, are a primary cause of death and disability. In 2010, the Global Burden of Disease study reported that over 11 million deaths worldwide were due to dietary risk factors alone( 1 ). Dietary patterns and food preferences developed in childhood are known to track into adulthood and influence the risk of future chronic disease( Reference Shrestha and Copenhaver 2 ). Therefore, developing healthy eating patterns in childhood is recommended by the WHO as a key chronic disease prevention strategy( Reference Waxman 3 ).

Childcare services are an important setting for public health intervention. Systematic review evidence suggests that improvements to the childcare nutrition environment can have a positive impact on child dietary intake( Reference Mikkelsen, Husby and Skov 4 ). Australian childcare services are required to comply with licensing and accreditation standards as outlined in the National Quality Framework. There are seven National Quality Standards (NQS) which provide a national benchmark for services, allowing for assessment of the quality of each childcare service. Of particular relevance to the present study is NQS 2, ‘children’s health and safety’, which states that childcare services implement policies and practices to support children’s health and well-being, and makes specific reference to the provision of healthy foods( 5 ). Childcare services also provide access to a large number of children for prolonged periods of time at a critical stage of development( Reference Mikkelsen, Husby and Skov 4 ). In Australia, 52 % of children up to 6 years of age attend formal care at a pre-school or a long day care centre( 6 ) for on average 18 h/week and can consume a large proportion (50–67 %) of their daily dietary requirements during attendance( Reference Radcliffe, Cameron and Baade 7 , 8 ).

Many countries, including Australia, Canada and England, recommend that childcare services provide foods to children consistent with their national dietary guidelines( 9 , Reference Benjamin Neelon and Briley 10 ). International and Australian research, however, suggests that foods and beverages provided by services often do not meet dietary guideline recommendations. Assessment of menus from 118 nurseries in England found that all childcare service menus failed to comply with sector nutrition guidelines( 11 ). Furthermore, an analysis of lunch menus from eighty-three childcare centres in Oklahoma, USA concluded that the menus did not provide sufficient carbohydrates, dietary fibre, iron, vitamin D and vitamin E; and provided excessive sodium. Similarly, in Australia, a menu audit of forty-six long day care service menus found that no service provided food that was compliant with all sector nutrition guideline recommendations( Reference Yoong, Skelton and Jones 12 ).

Without implementation, childcare dietary guidelines cannot yield improvements in child health. Few trials, however, have been conducted to assess how to best support the implementation of nutrition guidelines in this setting. A recent Cochrane review (2017) found only two randomised trials of interventions targeting the implementation of dietary guidelines( Reference Gosliner, Paula and Yancey 13 , Reference Johnston Molloy, Kearney and Hayes 14 ). While both studies demonstrate that implementation strategies such as staff professional development and ongoing support may be effective at improving food provision, neither study measured the impact of improving food provision on child dietary intake.

Given the limited research available in this field, the primary aim of the present study was to assess, relative to usual care, the effectiveness of a multi-strategy implementation intervention in improving childcare compliance with nutrition guidelines. As a secondary aim, the impact on service-level child dietary intake was also assessed.

Methods

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (reference 06/07/26/4.04) and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (reference H-2012-0321). The trial was registered on the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ID: ACTRN12615001032549).

Design and setting

A detailed protocol has been published elsewhere( Reference Seward, Wolfenden and Finch 15 ). A randomised controlled trial was conducted with childcare services, specifically long day care services in a single local health district in the state of New South Wales, Australia. There are currently 368 childcare services in the study region, of which the 106 long day care services that prepare and provide food onsite to children while in care served as the sampling frame.

Participants

Eligible childcare services were those that prepared and provided one main meal and two mid-meals to children while in care, and that were open for at least 8 h/d. Services that did not prepare and provide meals to children onsite or that did not have a cook with some responsibility for menu planning were excluded. Services catering exclusively for children requiring specialist care, mobile pre-schools and family day care centres were also excluded, given the different operational characteristics of these services compared with centre-based long day care services.

Recruitment procedures

Service managers were mailed information about the study approximately one week prior to recruitment. A random number function in Microsoft® Excel 2010 was used to determine the order at which services were approached to participate in the study. Services were telephoned and consent was obtained through the service manager agreeing to provide the service’s current two-week menu for baseline assessment.

Randomisation and allocation

When consent was obtained via telephone, consenting childcare services were immediately randomly allocated to an intervention or control group in a 1:1 ratio via block randomisation using a random number function in the statistical software package SAS version 9.3. Block size ranged between 2 and 6. All trial outcome data collectors were blinded; however, childcare service staff were aware of their group allocation.

Implementation intervention

The implementation intervention was delivered to participating childcare services over a 6-month period. Given their primary role in menu planning and the food preparation process in such services, long day care service managers and service cooks were the service personnel targeted by the intervention.

The multi-strategy implementation intervention was developed by an experienced team of health promotion practitioners, implementation scientists, dietitians and behavioural scientists in consultation with childcare service cooks and service managers( Reference Wolfenden, Yoong and Williams 16 ). The intervention aimed to increase the implementation of the sector nutrition guidelines by addressing barriers and enablers to the implementation of such guidelines, and was developed based on the Caring for Children resource (which outlines the nutrition guidelines for childcare services in the state of New South Wales included in Table 1)( 17 ), the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and previous research conducted in the childcare setting( Reference Cane, O’Connor and Michie 18 – Reference French, Green and O’Connor 21 ).

Table 1 Recommended daily servings of food groups to be provided to children aged 2–5 years who attend childcare for ≥8 h daily in New South Wales, Australia

Application of the Theoretical Domains Framework

The TDF( Reference French, Green and O’Connor 21 – Reference Hujg, Gebhardt and Crone 24 ) is an integrative theoretical framework of factors considered to influence behaviour change and incorporates thirty-three theories of behaviour change. The framework includes fourteen health behaviour change domains thought to play a role in successful implementation of best practice guidelines and policies, and has been empirically validated in the childcare as well as health-care settings( Reference Cane, O’Connor and Michie 18 , Reference French, Green and O’Connor 21 , Reference Phillips, Marshall and Chaves 25 – Reference French, McKenzie and O’Connor 30 ). The TDF was used to develop a semi-structured interview, completed with a convenience sample of seven centre-based childcare service cooks, to identify factors (barriers and enablers) that influenced childcare services’ implementation of nutrition guidelines. The factors identified in these interviews informed the selection and design of the implementation intervention strategies.

Intervention strategies

The implementation intervention consisted of the following strategies:

-

1. Securing executive support( Reference Jones, Riethmuller and Hesketh 31 ). A memorandum of understanding outlining each party’s responsibilities to implement the nutrition guidelines was signed by the implementation support officer, the service manager and the service cook. Service managers were also asked to communicate support and endorsement of adhering to nutrition guidelines to other staff and update the service nutrition policy accordingly (if required).

-

2. Provision of staff training( Reference Forsetlund, Bjørndal and Rashidian 32 – Reference Read and Kleiner 35 ). A one-day face-to-face menu-planning workshop was provided to service managers and cooks aiming to improve their knowledge and skills in the application of nutrition guidelines to childcare food service. The workshop incorporated both didactic and interactive components including small group discussions, case studies, facilitator feedback and opportunities to practice new skills. Experienced implementation support staff and dietitians facilitated the workshop.

-

3. Provision of resources( 17 ). All intervention services received a resource pack to support the implementation of the nutrition guidelines which included the Caring for Children resource, menu-planning checklists, recipe ideas and budgeting fact sheets.

-

4. Audit and feedback( Reference Ivers, Jamtvedt and Flottorp 36 ). Intervention services had a dietitian complete an audit of their two-week menus at two time points (baseline and mid-intervention), with written and verbal menu feedback provided at each time point.

-

5. Implementation support( Reference Abraham and Michie 37 , Reference Soumerai and Avorn 38 ). Intervention services were each allocated an implementation support officer to provide expert advice and assistance to facilitate nutrition guideline implementation. Each implementation support officer offered two face-to-face contacts with the service following the menu-planning workshop. In addition to the support visits, two newsletters were also distributed to intervention services during the intervention period.

Control group

Services randomised to the control group were posted a hard copy of the Caring for Children resource and received usual care from the local health district health promotion staff. The control services did not receive any other implementation support from the research team.

Data collection procedures and measures

Service cook demographics and menu-planning practices

Service cooks were asked to complete a mailed pen-and-paper questionnaire at baseline and follow-up. Data collected by the questionnaire included data regarding the service cook (education level, years employed as a service cook, age, weekly hours worked) and information about their menu-planning processes and the provision of healthy foods (such as how frequently the service plans a menu) in their service. Questionnaire items were adapted from items previously used in a state-based survey of childcare service providers conducted by the research team( Reference Dodds, Wyse and Jones 39 ).

Childcare service operational characteristics, nutrition environment and menu-planning practices

Service managers were also asked to complete a pen-and-paper questionnaire mailed to them at baseline and follow-up. The questionnaire captured childcare service operational characteristics (including the hours of operation; the total number of children who are enrolled at the service; and the number of children who attend each day) and the service nutrition environment (including presence of a nutrition policy; role modelling behaviour of staff; and staff provision of positive comments and prompts to children during meal times). The items used in the questionnaire have been used in previous Australian surveys of childcare service managers conducted by the research team( Reference Dodds, Wyse and Jones 39 , Reference Finch, Wolfenden and Falkiner 40 ).

Primary trial outcomes: compliance with nutrition guidelines

Services provided a copy of their current two-week menu to the research team. An independent dietitian, blinded to group allocation, assessed the menu and calculated servings of food groups per child based on the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating (AGHE) food groups. Menu compliance with nutrition guidelines was assessed via a comprehensive menu assessment undertaken by a dietitian in accordance with best practice protocols at baseline and follow-up( Reference Seward, Wolfenden and Finch 15 , Reference Ginani, Zandonadi and Araujo 41 ). Compliance to the nutrition guidelines was determined based on the calculations of servings of each food group provided per child each day. The calculated servings of each food group were rounded to the nearest 0·25 of a serving.

Two primary trial outcomes were assessed:

-

1. Full compliance with nutrition guidelines. Guidelines for the sector indicate menus must provide 50 % of the recommended daily servings of the five food groups specified in the AGHE across a two-week menu cycle (ten days). Specifically, to be fully compliant, services must list on their menu each day for two weeks: (i) 2 servings of vegetables and legumes/beans; AND (ii) 1 serving of fruit; AND (iii) 2 servings of wholegrain cereal foods and breads; AND (iv) 0·75 servings of lean meat and poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, seeds and legumes; AND (v) 1 serving of milk, yoghurt, cheese and alternatives (see Table 1)( Reference Wolfenden, Yoong and Williams 16 ). Full compliance was defined as the proportion of services providing food servings (per child) compliant with nutrition guideline recommendations for all five food groups across all ten days of a two-week menu.

-

2. Compliance with nutrition guidelines for individual AGHE food groups. Six measures were used to assess compliance with nutrition individual guideline recommendations for each of the five food groups specified above and discretionary foods. Discretionary foods are those which are high in kilojoules, saturated fat, added sugars and added salt, and are not recommended for provision in childcare services. Specifically, for this outcome, we assessed the proportion of services providing, across every day of a two-week menu, the recommended servings of each food group listed in Table 1, as well as discretionary foods( 17 ).

Secondary trial outcomes

Two secondary outcomes were also included to provide greater description of any changes occurring in the primary measures of menu compliance. These measures were not prospectively registered:

-

3. Menu compliance score (mean number of compliant food groups). A score for menu compliance was generated by summing the number of food groups and discretionary foods provided in sufficient quantity to meet guideline recommendations for each service. Mean score could range between 0 and 6, with a score of 1 allocated for each of the food groups of (i) vegetables and legumes/beans; (ii) fruit; (iii) wholegrain cereal foods and breads; (iv) lean meat and poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, seeds and legumes; (v) milk, yoghurt, cheese and alternatives), as well as for ‘discretionary’ foods.

-

4. Mean number of servings of each food group provided. The mean number of servings of each food group and discretionary foods listed on menus was also assessed.

Theoretical Domains Framework constructs

At post intervention, TDF constructs (knowledge, skills, professional role and identity, optimism, reinforcement, goals, environmental context and resources, social influences) targeted by the intervention were assessed via an online survey completed by service cooks for both intervention and control groups. The survey included sixty-one-items covering the fourteen TDF domains and was previously validated with long day care service cooks in Australia( Reference Seward, Wolfenden and Wiggers 29 ). Cooks were asked to rate their barriers and enablers to implementing the sector nutrition guideline on a 7-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. The study measured only the post-intervention difference in the TDF domains as awareness of the sector nutrition guidelines at baseline was low.

Service-level child food group consumption

Child consumption was assessed in a sub-sample of twenty-eight randomly selected (intervention, n 15; control, n 13) services. The aggregate servings of each of the core food groups and ‘discretionary’ foods consumed by children, for two mid-meals and one main meal while in care, was assessed at the service level at baseline and follow-up. Plate waste data were collected by two trained research assistants during a full-day data collection site visit at each time point. On the day of data collection, the research assistants collected the services’ menu and the pre- and post-serving weights of two mid-meals (morning and afternoon tea) and one main meal (lunch). The process for collecting plate waste measures was based on procedures previously reported in the literature( Reference Jacko, Dellava and Ensle 42 ) and is detailed in the published protocol paper( Reference Seward, Wolfenden and Finch 15 ).

Contamination, co-intervention and context

Intervention contamination and receipt of other interventions that may have influenced menu planning and food preparation was assessed in both intervention and control groups at follow-up via pen-and-paper questionnaires completed by service cooks and service managers.

A systematic search to identify any changes in government policy, standards, sector accreditation requirements and nutrition guidelines that may impact on the healthy eating environment and the provision of healthy foods within the childcare setting, was conducted to aid the assessment of the external validity of the trial findings and to describe the context in which the trial was conducted. The search was based on procedures applied in previous implementation trials in this setting( Reference Jones, Wyse and Finch 19 ) and involved reviewing local news archives, websites of national and New South Wales health and education departments, accreditation standards and national healthy eating guidelines, to identify the existence of or changes in government policy, standards, funded programmes or guidelines that may influence the healthy eating environments of childcare services. The search included the 12 months prior to and during the 6-month intervention.

Adverse effects

Information on adverse effects was assessed via items included in the cooks’ pen-and-paper questionnaire completed at baseline and follow-up. Measures included: (i) receipt of negative feedback about the service menu in the last month (received from educators, children and/or parents); and (ii) the estimated average percentage of each meal not consumed by the children and classified as waste (morning tea, lunch, afternoon tea).

Intervention delivery

Project records maintained by implementation support staff were used to monitor the delivery of the intervention strategies.

Sample size and power calculations

Compliance with nutrition guidelines

Based on results of a preliminary study undertaken by the research team, the recruitment of twenty-nine services in the intervention group and twenty-nine services in the control group will enable the detection of an absolute difference of 32 % between groups in the primary outcome at follow-up, allowing for a 13 % overall compliance rate in the control group, with 80 % power, with a two-sided α of 0·05. If the intervention were made available to all services within New South Wales, approximately 1118 childcare services (~30 %) in the state would be compliant with the state guidelines, impacting on the diet of thousands of children who attend these services.

Statistical analyses

The SAS statistical software package (version 9.3 or later) was utilised for all statistical analyses. Socio-economic characteristics were determined using service postcodes, which were classified as being in the top or bottom 50 % of New South Wales according to the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas( 43 ). All statistical tests were two-tailed with an α value of 0·05 and all available data were used for the analysis. All trial outcomes were analysed under an intention-to-treat framework using all available data with services analysed based on the groups to which they were allocated, regardless of the treatment type or exposure received. Logistic regression models, adjusted for baseline values of the outcome, were used to determine effectiveness of the intervention in improving full compliance with nutrition guidelines and compliance with nutrition guidelines for individual AGHE food groups. Linear regression models, adjusted for baseline values of all outcomes, were used to determine effectiveness of the intervention on modifying the mean number of compliant food groups, the mean number of servings of each food group planned on the service menu and the mean number of servings consumed for each AGHE food group and ‘discretionary’ foods. Analyses using multiple imputations for missing data were also performed.

Similar to previous studies, average scores for each TDF construct were calculated by summing all scores for all items within the domain (‘strongly disagree’=1 to ‘strongly agree’=7) and dividing by the total number of responses within the domain. The t test was used to assess between-group differences on TDF constructs at follow-up.

Results

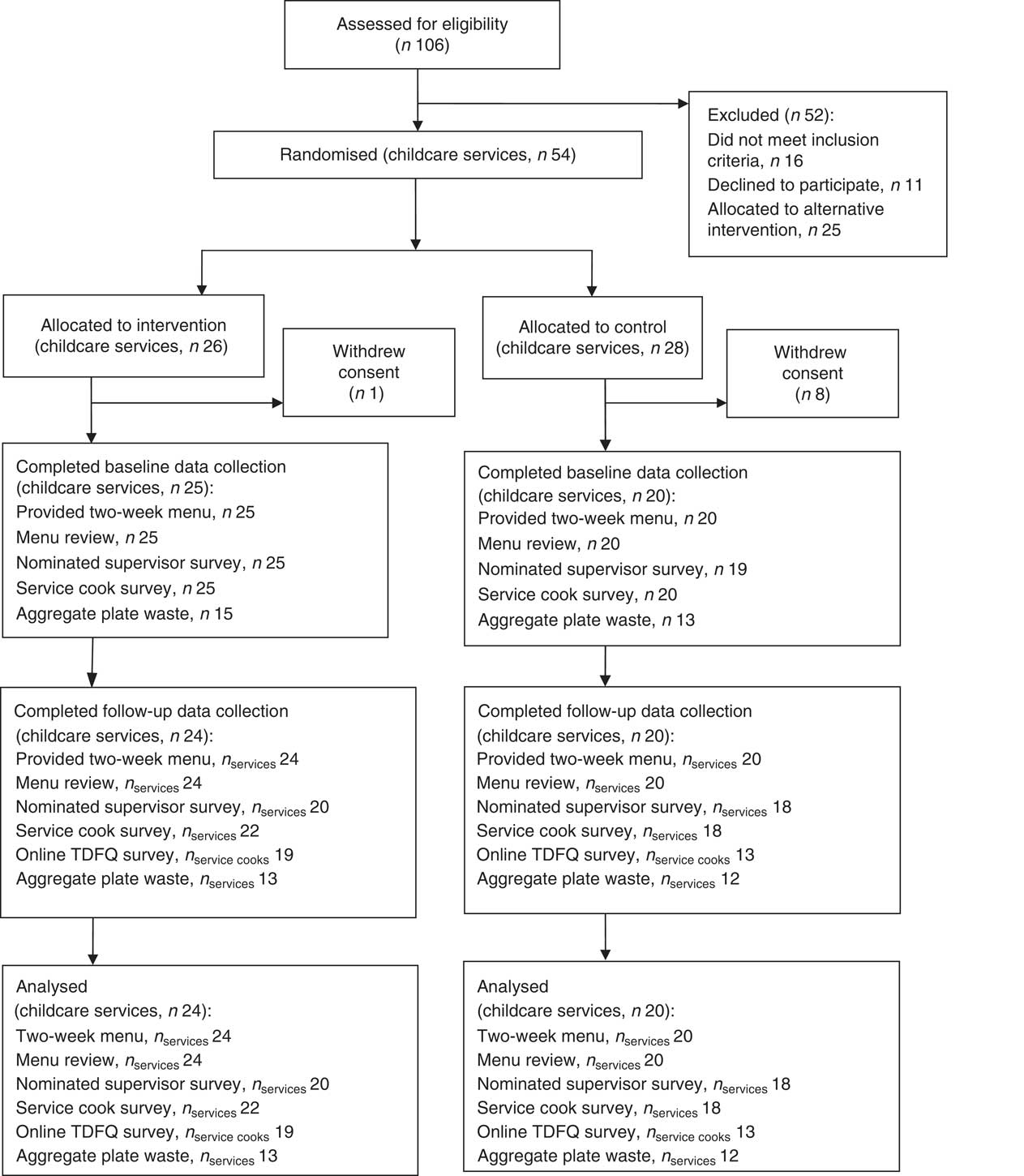

Of the 106 long day care services in the study region that were eligible, ninety (85 %) nominated supervisors were eligible, seventy-nine (88 %) consented for their service to participate in the study and fifty-four were randomised into the study (intervention, n 26; control, n 28). The remaining twenty-five services were allocated to receive an alternative intervention consisting of training only due to service team resource availability (Fig. 1). Of the fifty-four services in the study, nine services (intervention, n 1; control, n 8) withdrew consent prior to baseline data collection and without knowledge of group allocation. Only one service did not complete follow-up data collection. The baseline characteristics of the long day care services are described in Table 2. There was a significant difference in cooks’ qualifications between the intervention and control services (52 % had university or TAFE qualification in the intervention services v. 90 % in the control; P ≤ 0·05).

Fig. 1 Retention of long day childcare services throughout the randomised controlled trial of a multi-strategy implementation intervention aimed to improve childcare compliance with nutrition guidelines (TDFQ, Theoretical Domains Framework questionnaire)

Table 2 Baseline characteristics of long day childcare services and service cooks from Hunter New England region, New South Wales, Australia, participating in the randomised controlled trial of a multi-strategy implementation intervention aimed to improve childcare compliance with nutrition guidelines

SEIFA, Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas.

* Eleven intervention services and eleven control services completed the survey item.

† Twenty-four intervention services completed the survey item.

‡ Nineteen control services completed the survey item.

Primary trial outcomes

Full compliance with nutrition guidelines

At follow-up, one intervention service (4 %) and zero control services were fully compliant with the sector nutrition guidelines (all 5/5 food groups; see Table 3). Statistical analyses were not able to be performed given zero values across multiple cells.

Table 3 Baseline and follow-up results for the outcomes: full compliance with nutrition guidelines, compliance with nutrition guidelines for individual AGHE food groups and mean number of servings of each food group planned on the service menu, among long day childcare services from Hunter New England region, New South Wales, Australia, participating in the randomised controlled trial of a multi-strategy implementation intervention aimed to improve childcare compliance with nutrition guidelines

AGHE, Australian Guide to Healthy Eating.

Compliance with nutrition guidelines for individual AGHE food groups

Relative to control, significantly greater compliance among services allocated to the intervention group was reported for four of the six food groups: fruit (OR=10·84; 95 % CI 1·19, 551·20; P=0·0024); meat and meat alternatives (OR=8·83; 95 % CI 1·55, –; P=0·023); dairy (OR=8·41; 95 % CI 1·60, 63·62; P=0·006); and discretionary foods (OR=17·83; 95 % CI 2·15, 853·73; P=0·002; see Table 3).

Secondary trial outcomes

Menu compliance score (mean number of compliant food groups)

There was a significant difference between groups at follow-up in the mean number of food groups compliant (mean difference=1·57; 95 % CI 0·82, 2·33; P ≤ 0·001) favouring the intervention services.

Mean number of servings of each food group provided

There were significant differences (Table 3) between groups at follow-up in the mean number of servings of each food group planned on the menu for all six of the food groups.

Theoretical Domains Framework constructs

At follow-up there was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups in the TDF domain scores that were targeted by the intervention: knowledge (P=0·45); skills (P=0·21); social/professional role and identity (P=0·12); reinforcement (P=0·99); goals (P=0·37); environmental context and resources (P=0·77); and social influences (P=0·75).

Service-level child food group servings consumption

Significant improvements in consumption in the intervention services, relative to control, were found for two out of the six food groups: vegetables (adjusted difference=0·70; 95 % CI 0·33, 1·08; P<0·001); and fruit (adjusted difference=0·41; 95 % CI 0·09, 0·73; P=0·014; see Table 4).

Table 4 Service-level child food group serving consumption at baseline and follow-up among long day childcare services from Hunter New England region, New South Wales, Australia, participating in the randomised controlled trial of a multi-strategy implementation intervention aimed to improve childcare compliance with nutrition guidelines

Contamination, co-intervention and context

At follow-up, no intervention and no control service cooks or service managers reported receiving any additional intervention or support beyond the prescribed intervention.

The systematic search undertaken did not identify any changes in childcare government policy, standards, sector accreditation requirements and nutrition guidelines related to healthy eating environment and the provision of healthy foods within the childcare setting. However, the trial was conducted concurrently with a state-wide childhood obesity prevention initiative where by services were eligible to receive training or support regarding healthy eating and physical activity, which may have included support or training to improve food provision( 44 ). Internal service records identified ten services (intervention, n 5; control, n 5) that had completed the state-wide training between the specified period (12 months prior to intervention delivery and during the 6-month intervention). For all except one service (intervention), the training was completed by service educators.

Adverse events

At follow-up there was no significant difference, after adjusting for baseline values, observed between groups for service cooks reporting negative feedback received about the service menu in the past month from educators (intervention 32 % (n 7/22) v. control 25 % (n 4/16); P=0·62), children (intervention 32 % (n 7/22) v. control 6 % (n 1/16); P=0·07) or parents (intervention 9 % (n 2/22) v. control 0 % (n 0/16); P=0·95).

At follow-up there was also no significant difference, after adjusting for baseline values, observed between groups for the estimated average percentage of food classified as waste for each meal: morning tea (adjusted difference=−0·41; 95 % CI −2·35, 1·52 %; P=0·66); lunch (adjusted difference=3·31; 95 % CI −2·64, 9·27 %; P=0·26); and afternoon tea (adjusted difference=−1·24; 95 % −3·77, 1·28 %; P=0·31).

Delivery of intervention strategies

All services were offered and accepted six months of implementation support via telephone contact from an implementation support staff member. Over 90 % of intervention services signed the memorandum of understanding, received all of the intervention resources and newsletters, participated in two service visits, completed the mid-point menu review and were provided with a feedback report. Eighty-eight per cent of nominated supervisors and 92 % of service cooks attended the one-day menu-planning workshop.

Discussion

The present study is one of the few randomised controlled trials measuring the effectiveness of a multicomponent implementation intervention on childcare service compliance with nutrition guidelines. The study found that the intervention improved compliance with individual core food groups (fruit; meat and meat alternatives; dairy; and discretionary foods) and that child intake of some core foods (vegetables and fruit) increased as a consequence. In addition, the intervention had no adverse effects on food wastage or the service receiving negative feedback about the menu. Such findings provide one approach for policy makers and service delivery organisations to enhance childcare service guideline compliance and children’s intake of healthy foods while in care.

The intervention did not improve full compliance with nutrition guidelines, however. This finding suggests that achieving a fully compliant two-week menu represents a considerable challenge for centre-based childcare services – even with comprehensive implementation support. The findings also support those of reviews of implementation practice guidelines which suggest that perfect compliance with guideline recommendations is rarely achieved( Reference Durlak and DuPre 45 ). In retrospect, the primary trial outcome selected for the trial may have been unrealistic, given the complexity of menu-planning processes and of the operating environments of childcare services. While the Caring for Children resource represents an attempt to develop guidelines that are acceptable and suitable for the childcare setting, the complexity with planning meals and beverages so that they meet the recommended servings for all core food groups is likely to represent a significant challenge for cooks who do not typically have any formal training in nutrition. Future updates to the guidelines should consider that full compliance is unlikely to be achievable in this context, Generally, this is a key finding for the formation and measurement of nutrition guideline compliance in the setting.

Nevertheless, improvements in food provision were achieved. The magnitudes of improvements in implementation of menus compliant with four of six individual food groups (fruit, meat and alternatives, dairy, discretionary) achieved by intervention services (21·5 % for fruit; 25·2 % for meat and alternatives; 22·5 % for dairy; 50·0 % for discretionary) were somewhat similar to yet slightly lower than those reported among trials using similar implementation strategies in childcare services to improve menus (40–68 %)( Reference Gosliner, Paula and Yancey 13 , Reference Johnston Molloy, Kearney and Hayes 14 , Reference Bell, Davies and Finch 46 , Reference Williams, Bollella and Strobino 47 ). The effect sizes were also similar to those reported in trials of implementation strategies in schools to improve the availability of healthy foods (25–42 %)( Reference Bell, Davies and Finch 46 , Reference Nathan, Wolfenden and Bell 48 ). The findings of the present study, therefore, reinforce the capacity to improve food provision in line with menu dietary guidelines in education settings as a potentially effective public health nutrition strategy.

Despite significant improvements among intervention services in the mean servings planned on the menu for all six food groups, changes in service-level child consumption improved significantly for vegetables (0·70 servings) and fruit (0·41 servings) only. The findings indicate that improvements in food availability do not uniformly translate into improvements in intake. Statistical significance aside, smaller improvements in consumption of foods relative to improvements reported in menu availability were also reported across other food groups. Additional strategies beyond targeting foods provided, such as the use of positive statements during meal times and educators’ role modelling healthy eating behaviours, and addressing other known determinants of child intake may be required to improve the effectiveness of the intervention on child diet.

Interestingly, the implementation strategy did not change the TDF constructs that it targeted. The findings may suggest that the intervention exerts its effects in improving menu planning and food provision through other pathways. Future research to identify such pathways is warranted. Alternatively, the findings may reflect challenges in measurement of implementation constructs. While validated, and used in previous randomised trials, TDF scores for a number of constructs were high and skewed. Such ceiling effects may hinder the capacity of the measure to detect meaningful changes in hypothesised implementation mediators. Work to improve the TDF questionnaire tool in the childcare setting and the measurement of implementation constructs more broadly would be valuable for future research in the field.

Strengths of the study include the randomised controlled trial design, the application of theory for intervention design and the blinding of outcome assessors. However, the study findings should be considered in the context of its limitations. Previous studies have identified that time is a key determinant of implementation( Reference Gabor, Mantinan and Rudolph 49 , Reference Hughes, Gooze and Finkelstein 50 ). The short intervention period of 6 months may have not have provided sufficient time for the intervention services to reach full compliance, particularly considering the complexity of the menu-planning process. Second, with such a short intervention period, we do not know if the changes will be sustained long term. Future research is warranted to assess the sustainability of such interventions. Finally, the research was conducted in a region in which childcare services have been exposed to obesity prevention intervention and implementation support for more than a decade( Reference Jones, Wyse and Finch 19 , Reference Finch, Wolfenden and Falkiner 40 , Reference Bell, Davies and Finch 46 , Reference Bell, Hendrie and Hartley 51 ). The effects of the implementation strategies on services operating under different contexts are unknown.

Conclusion

The present study is one of the few randomised controlled trials measuring the effectiveness of a multicomponent support intervention on the implementation of menu dietary guidelines in the childcare setting. The findings indicate that service-level changes to menus in line with dietary guidelines can result in improvements to children’s dietary intake. Despite the lack of effect on TDF constructs/outcomes, the chosen implementation strategies were effective in supporting practice change, despite a short intervention period. As such they should be considered for future programmes/interventions targeting dietary guideline implementation in the setting.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank members of the ‘Good for Kids Good for Life’ Early Childhood Education and Care advisory group. Financial support: This project was funded by the Priority Research Centre for Health Behaviour and received infrastructure funding from Hunter New England Population Health and the University of Newcastle. L.W. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship and a Heart Foundation Future Leaders Fellowship. Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests. Authorship: K.S. led the development of this manuscript. K.S., S.Y., L.W. and M.F. conceived the intervention concept. K.S., S.Y., L.W., M.F., J.W. and J.J. contributed to the research design and trial methodology. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of this manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (reference 12/08/15/5.01) and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (reference H-2012-0321).