The number of people with dementia is rising rapidly with increased longevity. Although dementia’s core symptom is cognitive deterioration, agitation is common, persistent and distressing. Nearly half of all people with dementia have agitation symptoms every month, including 30% of those living at home. Reference Ryu, Katona, Rive and Livingston1 Four-fifths of those with clinically significant symptoms remain agitated over 6 months, Reference Savva, Zaccai, Matthews, Davidson, McKeith and Brayne2 and 20% of those initially symptom-free develop symptoms over 2 years. Reference Savva, Zaccai, Matthews, Davidson, McKeith and Brayne2 Agitation in dementia is associated with poor quality of life, Reference Wetzels, Zuidema, de Jonghe, Verhey and Koopmans3 because it is unpleasant, impedes activities and relationships, causes helplessness and anger in family and paid caregivers, Reference Draper, Snowdon, Meares, Turner, Gonski and McMinn4 and predicts nursing home admission, Reference Morris, Morris and Britton5 where the agitated behaviour adversely influences the environment. Reference Draper, Snowdon, Meares, Turner, Gonski and McMinn4 Several reviews, including our previous systematic review, Reference Livingston, Johnston, Katona, Paton and Lyketsos6 considered all neuropsychiatric symptoms’ management together. We found direct behavioural management therapies (BMT) with the person with dementia and specific staff education had lasting effectiveness, but this may be limited to affective symptoms. 7 A recent meta-analysis of family caregiver interventions for overall neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia found an effect size of 0.23, but did not consider which symptoms improved. Reference Brodaty and Arasaratnam8

Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia are heterogeneous, therefore symptoms should be considered individually as successful strategies may differ. The one published, well-conducted systematic review of non-pharmacological management of agitation in dementia included only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published before 2004 in English or Korean; it found just 14 papers and evidence of effectiveness only for sensory interventions. Reference Kong, Evans and Guevara9 The review did not consider whether interventions were effective only during the intervention or whether the effect lasted longer; the settings in which the intervention had been shown to be effective (e.g. in the community or in care homes); or whether the intervention reduced levels of agitation symptoms and was preventive or treated clinically significant agitation.

Psychotropic medication was routinely used to treat agitation but is now discouraged since benzodiazepines and antipsychotics increase cognitive decline, Reference Bierman, Comijs, Gundy, Sonnenberg, Jonker and Beekman10 and antipsychotics cause excess mortality and are of limited efficacy. Reference Maher, Maglione, Bagley, Suttorp, Hu and Ewing11 Similarly, citalopram has some efficacy but has cardiac side-effects and reduces cognition. Reference Porsteinsson, Drye, Pollock, Devanand, Frangakis and Ismail12 Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine appear ineffective. Reference Howard, Juszczak, Ballard, Bentham, Brown and Bullock13,Reference Fox, Crugel, Maidment, Auestad, Coulton and Treloar14 Preliminary evidence suggests mirtazapine may reduce agitation. Reference Banerjee, Hellier, Dewey, Romeo, Ballard and Baldwin15 One RCT (not placebo-controlled) found analgesics improved agitation in people with dementia, with an effect size comparable to antipsychotics. Reference Husebo, Ballard, Sandvik, Nilsen and Aarsland16

Effective agitation management could in theory improve the quality of life of people with dementia and their caregivers, reduce distress, decrease inappropriate medication, enable positive relationships and activities, delay institutionalisation and be cost-effective. We aimed therefore to review systematically the evidence for non-pharmacological interventions for agitation in people with dementia, both immediately and longer-term; the costs of the successful interventions are reported in a separate paper. Reference Livingston, Kelly, Lewis-Holmes, Baio, Morris and Patel17

Method

We registered our protocol with the Prospero International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42011001370). We began electronic searches on 9 August 2011, repeating them on 12 June 2012. We searched PubMed, Web of Knowledge, British Nursing Index, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme Database, PsycINFO, NHS Evidence, System for Information on Grey Literature, The Stationery Office Official Publications website, the National Technical Information Service, INAHL and the Cochrane Library. Search terms were agreed in consultation with caregiver representatives, older adults and professionals. We hand-searched included papers’ reference lists and contacted all authors about other relevant studies. We translated eight non-English papers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies in any language that met the following criteria:

-

(a) the participants all had dementia, or those with dementia were analysed separately;

-

(b) the study evaluated non-pharmacological interventions for agitation, defined as inappropriate verbal, vocal or motor activity not judged by an outside observer to be an outcome of need, Reference Cohen-Mansfield and Billig18 encompassing physical and verbal aggression and wandering;

-

(c) agitation was measured quantitatively;

-

(d) a comparator group was reported or agitation was compared before and after the intervention.

We excluded studies if every individual was given psychotropic drugs or some participants received medication as the sole intervention. In this paper we report the highest-quality studies - randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with more than 45 participants - since none of the trials with a smaller sample size provided a full and appropriate sample size calculation.

Data extraction

The first 20 search results were independently screened by G.L. and L.K. to assess exclusion procedure reliability. No paper was excluded incorrectly. All other papers were screened by L.K. and E.L.H. If exclusion was unclear, L.K., E.L.H. and G.L. discussed and reached consensus. Data extracted from the papers (by L.K. and E.L.H.) included methodological characteristics; description of the intervention; whether the intervention was applied to the person with dementia, family caregivers or staff; statistical methods; length of follow-up; diagnostic methods; and summary outcome data (immediate and longer-term). Paper quality, including bias, was scored independently by L.K. and E.L.H., discussing discrepancies with G.L. and/or G.B. They used Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) RCT evaluation criteria (http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025); this approach gives points for randomisation and its adequacy, participant and rater masking, outcome measures validity and reliability, power calculations and achievement, follow-up adequacy, accounting for participants, and whether analyses were intention to treat and appropriate. Possible scores range from 0 to 14 (highest quality). Where a randomised design was used but the intervention was not compared with the control group, we considered this a within-subject design, for example the study by Raglio et al. Reference Raglio, Bellelli, Traficante, Gianotti, Ubezio and Villani19 We assigned CEBM evidence levels as follows:

-

(a) level 1b: high-quality RCTs (these were at least single-blind, had follow-up rates of at least 80%, were sufficiently powered, used intention-to-treat analysis, had valid outcome measures and findings reported with relatively narrow confidence intervals);

-

(b) level 2b: lower-quality RCTs.

Intervention categories

The authors L.K., E.L.H. and G.L. categorised the interventions independently and then by consensus. The interventions were activities; music therapy (protocol-driven); sensory interventions (all involved touch, and some included additional sensory stimulation such as light); light therapy; training paid caregivers in person-centred care or communication skills (interventions focused on improving communication with the person with dementia and finding out what they wanted), with and without supervision; dementia care mapping; aromatherapy; training family caregivers in behavioural management therapies or cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT); exercise; cognitive stimulation therapy; and simulated presence therapy.

Agitation level

We separated studies according to the inclusion criteria of participants in terms of level of symptoms of agitation: 1, no agitation symptom necessary for inclusion; 2, some agitation symptoms necessary for inclusion; 3, clinically significant agitation level; 4, level unspecified. We used the usual thresholds: a score above 39 on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI), Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, Dakheel-Ali, Regier, Thein and Freedman20 and a score above 4 on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) agitation scale, Reference Ryu, Katona, Rive and Livingston1 to denote significant agitation.

Statistical analysis

We decided a priori to meta-analyse when there were three or more RCTs investigating sufficiently homogeneous interventions using the same outcome measure, but no intervention met these criteria. To facilitate comparison across interventions and outcomes, where possible, we estimated interventions’ standardised effect sizes (SES) with 95% confidence intervals. Reference Hedges21 In some studies the outcome was measured and reported at several time-points during the intervention. We used data from the last time-point to estimate the SES, since individual patient data were not available to incorporate repeated measures in the calculation. We also recalculated results for studies not directly comparing intervention and control groups but reporting only within-group comparisons and with one-tailed significance tests, so some of our results differ from the original analysis.

Results

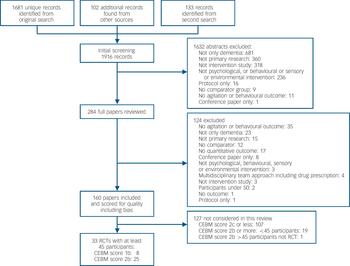

We found 1916 records, including 33 relevant RCTs with at least 45 participants (Fig. 1). Online Tables DS1 and DS2 list methodological characteristics, SES and quality ratings; Table DS1 contains the findings from interventions for which there appeared to be adequate evidence, and Table DS2 contains those for which there was not adequate evidence (either evidence that they were not effective or where there was simply insufficient evidence).

Efficacious interventions

Working with the person with dementia

Activities. Five of the included RCTs implemented group activities; those with standard activities reduced mean agitation levels, and decreased symptoms in care homes while they were in place. Reference Lin, Yang, Kao, Wu, Tang and Lin22,Reference Buettner and Ferrario23 One high-quality RCT found no additional effect on agitation of individualising activities according to functional level and interest, Reference Kolanowski, Litaker, Buettner, Moeller and Costa24 although two lower-quality RCTs did. Reference Kovach, Cashin, Taneli, Dohearty, Schlidt and Silva-Smith25,Reference Cohen-Mansfield and Jensen26 All studies were in care homes except one, in which some participants attended a day centre and others lived in a care home. Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Parpura-Gill and Golander27 None specified a significant degree of agitation for inclusion. Only one study measured agitation after the intervention finished, and did not show effects at 1-week and 4-week follow-up. Reference Kolanowski, Litaker, Buettner, Moeller and Costa24

Although activities in care homes reduced levels of agitation significantly while in place, there is no evidence regarding longer-term effect, and it is unclear whether individualising activities further reduces agitation. There is no evidence for activities in severe agitation or outside care homes.

Fig. 1 Study search profile (CEBM, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; RCT, randomised controlled trial).

Music therapy. Three RCTs, all in care homes, evaluated music therapy by trained therapists using a specific protocol - typically involving warming up with a well-known song, listening to and then joining in with the music. Reference Lin, Chu, Yang, Chen, Chen and Chang28-Reference Cooke, Moyle, Shum, Harrison and Murfield30 The largest study, which included participants irrespective of agitation level, found music therapy twice a week for 6 weeks was effective compared with the usual care group. Reference Lin, Chu, Yang, Chen, Chen and Chang28 A second study found a significant effect in comparison with a reading group, Reference Cooke, Moyle, Shum, Harrison and Murfield30 and the third found a borderline significant effect. Reference Sung, Lee, Li and Watson29 Reduction in symptoms of agitation was immediate (SES = 0.5-0.9). There is little evidence longer-term, and no evidence for people with severe agitation or outside care homes.

Sensory interventions

Five RCTs of sensory interventions, all in care homes, targeted perceived understimulation of people with dementia. Some focused on touch, such as massage; others were multisensory interventions of tactile, light and auditory stimulation, such as Snoezelen therapy. Reference Lin, Yang, Kao, Wu, Tang and Lin22,Reference Hawranik, Johnston and Deatrich31-Reference Van Weert, van Dulmen, Spreeuwenberg, Ribbe and Bensing34 Studies comparing touch found a significant improvement in symptomatic and clinically significant agitation compared with usual care. Reference Lin, Yang, Kao, Wu, Tang and Lin22,Reference Van Weert, van Dulmen, Spreeuwenberg, Ribbe and Bensing34 We report three ‘therapeutic touch’ studies; defined as a healing-based touch intervention focusing on the whole person. Reference Hawranik, Johnston and Deatrich31-Reference Woods, Beck and Sinha33 Despite therapeutic touch being efficacious in before-and-after analyses, in between-group analyses therapeutic touch tended towards being less efficacious than ordinary massage or usual treatment. Sensory interventions significantly improved symptomatic agitation and clinically significant agitation during the intervention, but therapeutic touch did not demonstrate added advantage, and there is insufficient evidence about long-term effects or in settings outside care homes.

Working through care-home staff

Person-centred care, communication skills training and dementia care mapping all seek to change the caregiver’s perspective, communication with and thoughts about people with dementia, encouraging the caregiver to see and treat them as individuals rather than being task-focused. Training paid caregivers in these techniques was investigated in five RCTs. Reference Chenoweth, King, Jeon, Brodaty, Stein-Parbury and Norman35-Reference Sloane, Hoeffer, Mitchell, McKenzie, Barrick and Rader39 All interventions included supervision during training and implementation.

Person-centred care. One high-quality study of person-centred care training found severe agitation significantly improved during the intervention and 8 weeks later. Reference Chenoweth, King, Jeon, Brodaty, Stein-Parbury and Norman35 Two studies of improving communication skills or person-centred care for participants with symptomatic agitation found significant improvements compared with the control group during the intervention, Reference McCallion, Toseland and Freeman37,Reference McCallion, Toseland, Lacey and Banks38 and up to 6 months afterwards. Reference McCallion, Toseland and Freeman37 A large study including participants without high agitation levels found agitation improved significantly during 8 weeks of person-centred care training and 20 weeks later. Reference Deudon, Maubourguet, Gervais, Leone, Brocker and Carcaillon36 One small study, where participants’ agitation levels were unspecified, showed immediate improvement in agitation during bathing compared with the control group. Reference Sloane, Hoeffer, Mitchell, McKenzie, Barrick and Rader39

Dementia care mapping. One large, high-quality care home study evaluated dementia care mapping. The researchers observed and assessed each resident’s behaviour, factors improving well-being and potential triggers; explained the results to caregivers, and supported proposed change implementation. Severe agitation decreased during the intervention and 4 months afterwards. Reference Chenoweth, King, Jeon, Brodaty, Stein-Parbury and Norman35

Effect sizes. Training paid care-home staff in communication skills, person-centred care or dementia care mapping with supervision during implementation was significantly effective for symptomatic and severe agitation immediately (SES = 0.3-1.8) and for up to 6 months (SES = 0.2-2.2). There was no evidence in other settings.

Interventions without evidence of efficacy

Working with the person with dementia

Light therapy. Light therapy hypothetically reduces agitation through manipulating circadian rhythms, typically by 30-60 min daily bright light exposure. We included three RCTs, all in care homes. Reference Ancoli-Israel, Martin, Gehrman, Shochat, Corey-Bloom and Marler40-Reference Dowling, Graf, Hubbard and Luxenberg42 Among participants with some or significant agitation, light therapy either increased agitation or did not improve it. The SES was 0.2 (for improvement) to 4.0 (for worsening symptoms) compared with the control group. There is therefore no evidence that light therapy reduces symptomatic or severe agitation in care homes and it may worsen it.

Aromatherapy. The two RCTs of aromatherapy both took place in care homes. Reference Ballard, O'Brien, Reichelt and Perry43,Reference Burns, Perry, Holmes, Francis, Morris and Howes44 One large, high-quality blinded study found no immediate or long-term improvement relative to the control group for participants with severe agitation. Reference Burns, Perry, Holmes, Francis, Morris and Howes44 The other, non-blinded, study found significant improvement compared with the control group. Reference Ballard, O'Brien, Reichelt and Perry43 When assessors are masked to the intervention, aromatherapy has not been shown to reduce agitation in care homes.

Training family caregivers in BMT. Two high-quality studies found no immediate or longer-term effect (at 3 months, 6 months or 12 months) of either four or eleven sessions training family caregivers in BMT for severe or symptomatic agitation in people with dementia living at home. Reference Gormley, Lyons and Howard45,Reference Teri, Logsdon, Peskind, Raskind, Weiner and Tractenberg46 Two studies training family caregivers in CBT for people with severe agitation also found no improvement compared with controls. Reference Wright, Litaker, Laraia and DeAndrade47,Reference Huang, Shyu, Chen, Chen and Lin48 There is thus high-quality evidence that teaching family caregivers BMT or CBT is ineffective for severe agitation, but insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding symptomatic agitation.

Interventions with insufficient evidence

For the following interventions there was insufficient evidence to make a definitive recommendation.

Exercise

There is no evidence that exercise is effective. The one sufficiently sized exercise RCT was conducted in a care home and found no effect on agitation levels either immediately or 7 weeks later.

Training caregivers without supervision

Training in communication skills and person-centred care without supervision was ineffective. Reference Magai, Cohen and Gomberg49,Reference Finnema, Droes, Ettema, Ooms, Ader and Ribbe50

Other interventions

One study found that simulated presence therapy - playing a recording mimicking a telephone conversation with a relative when the participant was agitated - was not effective. Reference Camberg, Woods, Ooi, Hurley, Volicer and Ashley51 One study testing a mixed psychosocial intervention, including massage and promoting residents’ activities of daily living skills, did not find agitation improved significantly compared with the control group. Reference Beck, Vogelpohl, Rasin, Uriri, O'Sullivan and Walls52

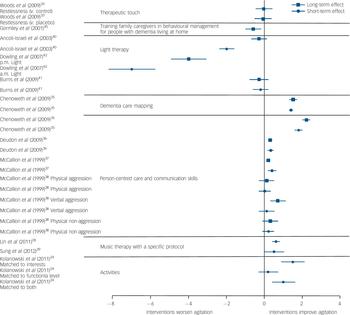

Standardised effect sizes

Figure 2 illustrates the effect of person-centred care, communication, dementia care mapping, music therapy and activities in reducing agitation. Long-term effects (in months) of changing the way caregivers interact with residents are at least as good as the short-term effects. Reference Chenoweth, King, Jeon, Brodaty, Stein-Parbury and Norman35,Reference McCallion, Toseland, Lacey and Banks38

Discussion

This is the first up-to-date systematic review to focus on agitation. It uniquely analyses whether the intervention was potentially preventive, by reducing mean levels of agitation symptoms including those not clinically significant at baseline or managed clinically significant agitation; whether effects were observed only while the intervention was in place or lasted longer; and the settings in which the intervention had been shown to be effective: the community or in care homes.

Effective interventions

Effective interventions seem to work through care staff, particularly in the long term. There is convincing evidence that when implementation is supervised, interventions that aim to communicate with people with dementia, helping staff to understand and fulfil their wishes, reduce symptomatic and severe agitation during the intervention and for 3-6 months afterwards. This suggests that training paid caregivers in communication, person-centred care skills or dementia care mapping are clinically important interventions, as shown by a 30% decrease in agitation Reference Ballard, O'Brien, Reichelt and Perry43 or a standardised effect size of 0.2, which is clinically small, 0.5 medium and 0.8 large. Reference Long53

Sensory interventions significantly improved agitation of all severities while in place. Therapeutic touch had no added advantage. We also found replicated, good-quality evidence that activities and music therapy by protocol reduce overall and symptomatic agitation in care homes while in place. Although we were surprised that individualised activities were no more effective than prescribed activities, the low numbers in the activity intervention groups may suggest that it was only those who were particularly suited to the activity who participated. There is no evidence for severe agitation. Theory-based activities (neurodevelopmental and Montessori) were no more effective than other pleasant activities.

Other interventions

Light therapy does not appear to be effective and may be harmful. Non-blinded interventions with aromatherapy appeared effective, possibly owing to rater bias, but masked raters do not find it effective. Training family caregivers in BMT and CBT interventions for the person with dementia was not effective. Learning complex theories and skills and maintaining fidelity to an intervention may be almost impossible to combine with looking after a family member with dementia and agitation on a 24-hour basis.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This is an exhaustive systematic review; two raters independently evaluated studies to ensure reliability in study inclusion and quality ratings. We searched all health and social sciences databases, translated non-English publications, reduced publication bias by searching the grey literature and asking experts about other studies, then repeated our searches. Some interventions were multicomponent and we made judgements about which category they belonged in and described them in the text. Most interventions had been tried only in care homes and we do not know their effect or practicality in people’s own homes where most people with dementia live. Although we excluded interventions in which all participants received medication, we cannot assess if medication use was uneven in different arms. Most studies included participants with any dementia and we cannot comment on the effect of interventions on different dementia subtypes.

Fig. 2 Standardised effect size and 95% confidence intervals where calculable of randomised controlled trials compared with controls for each reported outcome immediately and in the longer term.

Studies were heterogeneous in both intervention and measuring effects. This meant we were unable to meta-analyse and our conclusions are mostly based on a qualitative synthesis. Many studies were underpowered, possibly because residents were unwilling or unable to participate, or of low quality and therefore excluded. There were only eight level 1 studies and this is not evidence of lack of efficacy; there were several interventions with insufficient evidence to draw conclusions. Several interventions were implemented differently to usual practice and this may have altered the effect, for example in dementia care mapping. Reference Chenoweth, King, Jeon, Brodaty, Stein-Parbury and Norman35 Finally, although most studies used the CMAI many did not, and the definition of agitation varied between studies.

Other research

Early studies did not have the opportunity to use valid instruments for agitation; these now exist but may vary in their sensitivity to detect change. Differences in effect sizes between study results may therefore sometimes be due to instrument difference. Thus although our study’s strength is the literature integration, it underlines how much more work is needed. There are some RCTs currently in progress which should add to the evidence base. A recent study, considering overall neuropsychiatric symptoms (in contrast to our review specifically about agitation) found working with family caregivers to be effective, and it would be useful to examine which symptoms contributed to this effect and if it were mood rather than agitation. Reference Brodaty and Arasaratnam8

Study implications

Although agitation in dementia has been regarded as due to brain changes, our findings suggest agitation also arises from lack of understanding or unmet needs in someone whose dementia makes them unable to explain or understand this. This is in line with the need-driven, dementia-compromised behaviour theory of Algase et al, Reference Algase, Beck, Kolanowski, Whall, Berent and Richards54 and the hypothesis of Kitwood & Bredin that behaviours arise from need and occur when care is task-driven not person-centred (relevant to all neuropsychiatric symptoms). Reference Kitwood and Bredin55 Our findings suggest clinicians should stop considering agitation as an entity but instead often as a symptom of lack of understanding or unmet need that the person with dementia is unable to explain or understand. This may be physical discomfort or need for stimulation, emotional comfort or communication.

Future research

More evidence is required about implementing group activities in care homes over longer periods to prevent agitation. We recommend the development and evaluation of a manual-based training for staff in care homes employing interventions with evidence for efficacy, to allow translation to different settings. We suggest these interventions should focus on changing culture to implement programmes permanently. In general it seems that there is no evidence about settings outside care homes. The lack of effective interventions, despite 70-80% of people with dementia living at home and the potential of interventions to delay care home admission, suggests further research should start from qualitative interviews considering how agitation is experienced by people with dementia living at home, and how their families manage. This, together with synthesised evidence from other settings, could help in the development of a pilot intervention. Our review may suggest that it should have elements of sensory stimulation (including music), activities and teaching the family caregiver communication skills, to change themselves rather than the person with dementia.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Shirley Nurock, dementia family carer, for her thoughts and contributions.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.