Parents play a central role in the development and maintenance of their children’s early eating behaviours, and this role is particularly important during early childhood when children’s health-related behaviours are forming(Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Kim1,Reference Birch and Davison2) . Parents’ knowledge of nutrition; their influence over food selection, meal structure and home eating patterns; their modelling of healthful eating practices; and their parenting styles and practices all influence their children’s life-long eating habits that contribute to their weight status(Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Kim1,Reference Birch and Davison2) .

Although traditionally mothers have had the primary responsibility of child caregiving, fathers’ involvement in childcare has increased over the past decades(Reference Cabrera, Hofferth and Chae3–Reference Raley, Bianchi and Wang5). This increase has been linked to socioeconomic demands and to changes in the labour market with more women in the workforce(Reference Bianchi4,Reference Raley, Bianchi and Wang5) . Furthermore, changes in family structure have led to a decreased reliance on large extended family members, and increased participation of fathers in child care(Reference Hofferth and Lee6).

To date, most research examining parental influences on child’s feeding practices and eating has been conducted with mothers(Reference Shloim, Edelson and Martin7–Reference Lumeng, Ozbeki and Appugliese11). Overall, evidence indicates that maternal beliefs, attitudes, parenting feeding styles and practices are associated with children’s eating behaviours and weight status(Reference Shloim, Edelson and Martin7–Reference Lumeng, Ozbeki and Appugliese11).

Results from available studies conducted with Latino groups in the USA indicate that mothers are the primary caregivers responsible for their children’s feeding(Reference Gauthier and Gance-Cleveland12–Reference Lora, Cheney and Branscum21). Moreover, studies with Latina mothers indicate that their perceptions of child weight status are influenced by their personal, familial and cultural beliefs(Reference Gauthier and Gance-Cleveland12–Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney14,Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty17,Reference Lora, Cheney and Branscum21) . Such beliefs have been attributed to the mothers’ personal experiences with childhood poverty and food insufficiency(Reference Gauthier and Gance-Cleveland12,Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty17) . For example, a common belief held by Latina mothers is that a chubby baby is a healthy baby(Reference Gauthier and Gance-Cleveland12–Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney14,Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty17,Reference Lora, Cheney and Branscum21) . Furthermore, environmental factors such as access to, availability and cost of foods, food insecurity, immigration status, maternal acculturation, including dietary acculturation, etc., have all been found to influence mothers’ feeding practices(Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney13–Reference Evans, Chow and Jennings16,Reference Lora, Cheney and Branscum21–Reference Turner, Navuluri and Winkler23) .

Similarly, studies conducted with Brazilian immigrant mothers living in the USA have determined that sociocultural and environment transitions influence mothers’ beliefs and practices relating to child’s feeding and weight status(Reference Lindsay, Wallington and Greaney24–Reference Tovar, Hennessy and Must27). Time spent living in the USA and acculturation level also have been identified as factors affecting Brazilian immigrant mothers’ feeding styles and feeding practices, and their children’s eating habits(Reference Lindsay, Wallington and Greaney25–Reference Tovar, Choumenkovitch and Hennessy28). For example, Tovar et al. (Reference Tovar, Hennessy and Pirie26–Reference Tovar, Choumenkovitch and Hennessy28) in a community-based randomised controlled lifestyle intervention conducted with a diverse sample of immigrant mothers, including Brazilians, found that most mothers had low demanding/high responsive feeding styles, and these feeding styles were associated with higher child weight status.

Furthermore, previous studies have found that Brazilian immigrant mothers view themselves as being responsible for ensuring that their children eat healthfully(Reference Lindsay, Wallington and Greaney25–Reference Tovar, Hennessy and Must27). Nevertheless, these studies also show that Brazilian immigrant mothers also face a number of challenges such as social and environmental changes, pressures, demands and stress of raising a family in a new country to ensure their children’s healthy eating(Reference Lindsay, Wallington and Greaney25–Reference Tovar, Hennessy and Must27).

Increasingly research suggests that the fathers’ perspectives and practices should be considered when designing parenting and family interventions to promote healthy eating and prevent obesity among children(Reference Khandpur, Blaine and Fisher29–Reference Khandpur, Charles and Blaine31). Although research exploring the role and involvement of fathers in child’s feeding has expanded(Reference Lloyd, Lubans and Plotnikoff32–Reference Guerrero, Chu and Franke38), there is a dearth of research with minority immigrant fathers(Reference Harris and Ramsey36,Reference Lindsay, Wallington and Muñoz39) . Furthermore, most of the available research with Latino fathers has focused on Mexican immigrant fathers(Reference Parada, Ayala and Horton40–Reference Penilla, Tschann and Deardorff42).

A recent integrative review synthesising findings from studies examining Latino fathers’ role in promoting healthy eating and physical activity for their children determined that overall mothers are the primary decision-makers for their children’s eating, while fathers are more involved in their children’s physical activity and sedentary behaviours(Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43). Nonetheless, some of the qualitative studies included in this review found that fathers encouraged their children to eat healthy(Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43). However, like mothers, fathers faced barriers to modelling healthy eating and to ensuring their children develop healthy eating habits(Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43).

Findings from the same review also indicated that Latino fathers help determine what foods are available and served in their homes, and this was viewed as influencing their children’s eating(Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43). Moreover, some studies included in this review found that fathers are permissive about what their children eat, while mothers are more likely to report actively working to change their own or their family’s eating behaviours(Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43). Finally, an important finding of this review was that both Latino fathers and mothers seem to underestimate how influential fathers are in helping their children develop healthy eating behaviours(Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43).

Brazilians are a rapidly growing Latino immigrant group in the USA(Reference Lima and Siqueira44,Reference Jouët-Pastré and Braga45) , and a recent study conducted in Massachusetts with a multi-ethnic sample of immigrant mothers and children, including Brazilians, found that about 20 % of all the children aged 3–12 who participated in the study were overweight, and 25 % had obesity(Reference Tovar, Hennessy and Pirie26). Brazilians share many of the cultural characteristics as other Latin American population groups: however, Portuguese is the official language of Brazil, and this is an important cultural difference between Brazilians and other Latin American population groups whose predominant language is Spanish(Reference Lima and Siqueira44,Reference Jouët-Pastré and Braga45) .

As in other Latin American groups, family is a central aspect of Brazilian culture(Reference Lindsay, Wallington and Greaney25,Reference Jouët-Pastré and Braga45) . Children are viewed as their parents’ lifelong responsibility, and adult children until marriage often live with their parents(Reference Lindsay, Wallington and Greaney25,Reference Jouët-Pastré and Braga45) . Extended family members tend to have close ties, and grandparents are seen as an integral part of children’s rearing and parenting. Although gender equality has become more common in Brazil(Reference Jouët-Pastré and Braga45), some perceptions of appropriate gender roles remain. For example, the mother, in general, is seen as being the person who is most responsible for running the household and completing tasks such as food shopping, planning and preparing meals, housecleaning, etc.(Reference Jouët-Pastré and Braga45) Food is also a central part of Brazilian culture, and preparing and serving meals is often seen as an expression of love and care for family members(Reference Lindsay, Wallington and Greaney25,Reference Jouët-Pastré and Braga45) . Moreover, although Brazilian women may be important contributors to the family’s income, in general, Brazilian men view themselves as being responsible for and the main provider for the family(Reference Jouët-Pastré and Braga45).

To our knowledge, no research has examined the perspectives and practices relating to child’s eating and feeding of Brazilian immigrant fathers living in the USA. This research is needed to gain a more complete understanding of Brazilian immigrant parents’ influences on their children’s eating behaviours, and to identify factors that should be considered when designing family and parenting interventions to promote healthy eating and healthy weight status of children of Brazilian immigrant families in the USA. Therefore, the current study was designed to address this gap by exploring the perspectives and practices of Brazilian immigrant fathers relating to their preschool-aged children’s eating and feeding.

Methods

The present qualitative study was part of a larger ongoing mixed-methods research study with Brazilian immigrant families living in Massachusetts (to date 233 unique families) examining parenting styles and parenting practices relating to the risk of early childhood obesity (e.g. promoting healthy eating, physical activity and adequate sleep, as well as limiting screen time)(Reference Lindsay, de Oliveira and Wallington46–Reference Lindsay, Arruda and De Andrade50).

Theoretical framework

We used the socio-ecological model(Reference McLeroy, Bibeau and Steckler51) and the social contextual model(Reference Sorensen, Emmons and Hunt52) as frameworks for the current study. The socio-ecological model and the social contextual model consider the complex interplay of multi-level influences on health behaviours and outcomes(Reference McLeroy, Bibeau and Steckler51,Reference Sorensen, Emmons and Hunt52) . These models informed the development of an interview guide used in the current study and were also used to categorise emergent themes by multiple levels of influences: (i) individual (e.g. beliefs, attitudes, practices, daily hassles); (ii) interpersonal (e.g. family, friends, social support, social networks); (iii) environmental (e.g. exposure to different physical environments) and (iv) organisational (e.g. childcare programmes)(Reference McLeroy, Bibeau and Steckler51,Reference Sorensen, Emmons and Hunt52) .

Study design and sample

Using an exploratory descriptive qualitative methodology, we conducted one-on-one, semi-structured interviews with Brazilian immigrant fathers who had at least one child between 2 and 5 years of age(Reference Sandelowski53). We chose to conduct semi-structured interviews as they allow for the collection of valuable and in-depth information in diverse cultural settings(Reference Patton54,Reference Peters and Halcomb55) . In addition, individual interviews also address the challenge of gathering a group of immigrant fathers, who may have multiple jobs with irregular hours, to attend focus group discussions(Reference Peters and Halcomb55). The current study received ethical approval from the University of Massachusetts Boston’s Ethics Board (Internal Review Board no. 2013060).

Fathers were eligible to participate in the current study if they: (i) had at least one child aged 2–5 years, (ii) were of Brazilian ethnicity and born in Brazil, (iii) were ≥21 years of age, (iv) lived in Massachusetts, (v) had lived in the USA for at least 12 months and (vi) provided signed informed consent. Fathers were recruited for the current study using the same methods employed in the larger ongoing mixed-methods research study(Reference Lindsay, de Oliveira and Wallington46–Reference Lindsay, Arruda and De Andrade50). More specifically, purposive sampling was used to recruit a convenience sample of fathers through flyers posted at local Brazilian businesses and community-based social and health services agencies, and through announcements and events at predominant Brazilian churches. Interested participants called the telephone number listed on the flyer or spoke to study staff at church events(Reference Lindsay, de Oliveira and Wallington46–Reference Lindsay, Arruda and De Andrade50). Participants also were recruited through network sampling, a ‘word-of-mouth’ approach of acquiring participants(Reference Faugier and Sargeant56). Research staff that was native Brazilian immigrants and members of the Brazilian communities who participated in the study used their personal, family and community contacts to recruit participants. Moreover, participants also were recruited using a snowball sampling technique, with fathers enrolled in the study asking their Brazilian male friends with preschool-aged children if they would be interested in participating(Reference Faugier and Sargeant56).

All interested individuals were screened by research staff for study eligibility in-person or via telephone. After determining study eligibility, study staff scheduled interviews with eligible participants. In total, twenty-eight interested individuals contacted study staff between October 2017 and March 2018. Two of the twenty-eight participants did not meet study eligibility criteria (e.g. did not have at least one child between 2 and 5 years, had not lived in the USA for 12 months). Three eligible participants did not complete their scheduled interview despite follow-up calls and were classified as having dropped out of the study.

Data collection

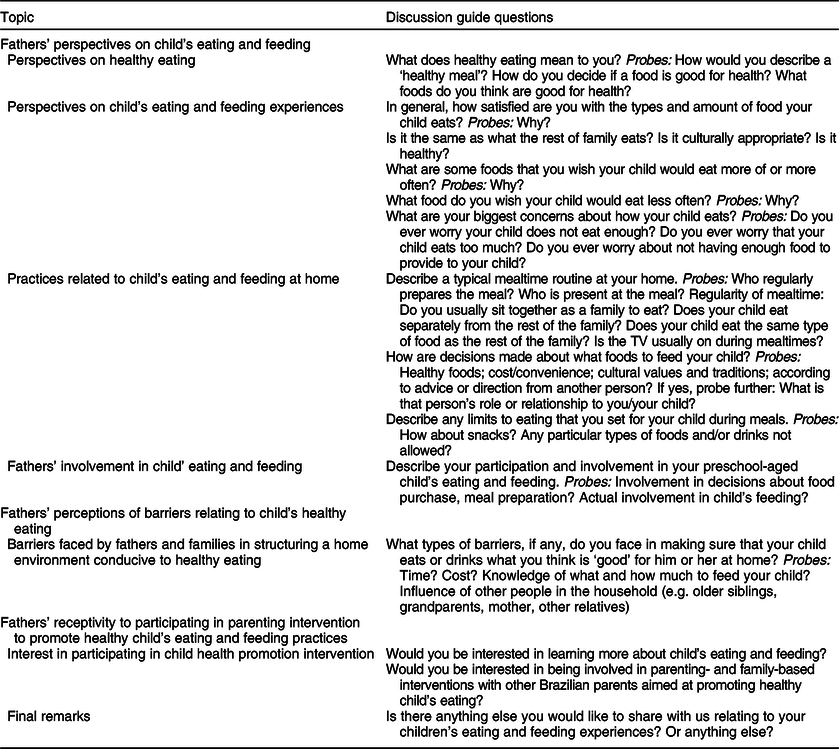

We interviewed twenty-three Brazilian immigrant fathers between November 2017 and April 2018. Interviews were conducted in Portuguese by one of two qualitative researchers who are native Brazilian-Portuguese speakers (G.V.B.V., A.C.L.) using a semi-structured discussion guide. The guide was pilot-tested with two Brazilian fathers, and these data were not included in the current study, but the results of these interviews were used to refine the guide prior to use in the subsequent twenty-one interviews. The guide, adapted from a previous study(Reference Lindsay, Wallington and Muñoz39) with Latino fathers, explored fathers’: (i) definitions of healthy eating, (ii) beliefs and attitudes relating to young children’s healthy eating, (iii) practices relating to children’s eating and (iv) barriers to children’s healthy eating. In addition, the guide explored fathers’ beliefs about physical activity and screen time, and these results are presented elsewhere (AC Lindsay, ASM Alves, GBV Vianna, CAM Arruda, MH Hasselmann, MM Tavares Machado and ML Greaney, unpublished results). Table 1 presents the questions with prompts from the interview guide.

Table 1 Questions from the interview guide relating to Brazilian immigrant fathers’ perspectives and practices of their preschool-aged children’s eating behaviours and feeding

Before each interview, the interviewers (G.V.B.V. or A.C.L.) explained study’s purpose and interview procedures in Portuguese, including confidentiality of information, and obtained written informed consent. In addition, participants were asked to think about their preschool-aged children (2–5 years) when answering all interview questions. A trained, bilingual (native Portuguese-speaker and English) research assistant (A.T.M.) took notes during all interviews, which were audio-recorded and lasted approximately 30–35 min.

At the end of each interview, participants completed a brief, self-administered questionnaire in Portuguese that assessed educational attainment, marital status, access to healthcare services, including participation in government-sponsored health and nutrition programmes (e.g., Special Supplemental Nutrition Programme for Women, Infants, and Children; Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programme, etc.), country of origin, and length of time living in the USA. In addition, participants’ acculturation level was assessed via the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics, a twelve-item scale validated for use in Latinos(Reference Marin, Sabogal and Marin57). Items are measured on a scale of 1–5 (1 = least acculturated, 5 = fully acculturated), and an acculturation score was computed by averaging across the twelve items. The Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics assesses language use, media use and ethnic social relations, and has a good reliability. Previous studies have found an overall Cronbach’s α reliability of 0·92–0·89, 0·89 for language use, 0·88 for media preference and 0·72 for ethnic and social relations(Reference Marin, Sabogal and Marin57,Reference Ellison, Jandorf and Duhamel58) . Participants received a $25 gift card at the end of the interview for their participation.

Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed within a few days of the interview. A professional transcriptionist and native Brazilian speaker transcribed all audio-recordings verbatim in Portuguese. The qualitative data were analysed manually using thematic analysis, an analytical approach that uses an iterative multistep process of coding data in phases to identify meaningful patterns(Reference Miles and Huberman59,Reference Braun and Clarke60) . A hybrid thematic analysis approach was used, which incorporated: (i) a deductive approach including a priori themes based on the socio-ecological model and social contextual model, and (ii) a data-driven inductive approach that allowed for new themes to emerge during analysis, thus expanding the possible a priori categories of themes(Reference Sandelowski53,Reference Patton54) .

Data collection and the preliminarily data analysis were undertaken concurrently(Reference Sandelowski53,Reference Patton54) . The interviewer and research assistant met for about 20 min after each interview to discuss recurring themes and identify new additional themes. Coded text describing similar ideas were grouped and sorted to identify themes and subthemes(Reference Sandelowski53,Reference Patton54,Reference Braun and Clarke60) . Themes were entered into a grid that was used to closely follow emerging themes and to determine when data saturation occurred, with no new themes emerging after the 14th–16th interview(Reference Sandelowski53,Reference Patton54,Reference Braun and Clarke60) .

After all twenty-one interviews were transcribed, two authors who are native Portuguese speakers (A.C.L., C.A.M.A.) read and manually coded all transcripts independently, but met regularly to discuss coding and to identify and resolve coding disagreements, with inputs from a third study member who is a native Brazilian (M.M.T.M.). Finally, salient text passages were extracted, and translated into English to illustrate emergent themes. It is important to note that content analysis was not the aim of the data analysis, and, consequently, a single comment was considered as important as those that were repeated across the interviews. Descriptive statistics and frequencies were calculated for the data collected by the sociodemographic survey using Microsoft Excel 2008.

Results

Twenty-one fathers participated in the current study, and their ages ranged from 27 to 43 (mean 34·4, sd 2·84) years. Fathers had lived in the USA for an average of 7·3 (sd 2·68) years, and their mean acculturation score was 1·21 (sd 0·77), indicating that they identified more closely with Brazilian than American culture. In contrast, the mean acculturation score for their children, as reported by the fathers, was 3·22 (sd 0·53), meaning that children more closely identified with American culture than Brazilian culture, although most fathers viewed their children as ‘bicultural’ (score of 2·5). Additional participants’ characteristics are provided in Table 2.

Table 2 Sociodemographic and acculturation characteristics of fathers (n 21)

Although we purposively recruited fathers with children aged 2–5 years, most fathers discussed their parenting and feeding practices and their children’s eating behaviours within the context of the entire family, including mothers, older children and extended family members (e.g. grandmothers, other older relatives). Emergent themes and subthemes identified during analyses are presented below with illustrative quotes. Additional representative quotes selected to illustrate themes and subthemes are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 Themes and subthemes with representative quotes (n 21)

Theme 1: Ethnicity and low dietary acculturation influence fathers’ beliefs about healthy eating and child’s feeding practices

Fathers defined healthy eating for themselves and their children in a variety of ways, although most offered definitions focusing on eating a balanced and traditional Brazilian diet that included rice, beans, meat, fruits and a variety of vegetables. Some fathers cited several vegetables common to the Brazilian diet, such as collard green, squash, okra, etc., as being healthy.

Fathers viewed food as being an important part of their Brazilian identity. They preferred that their children eat a traditional Brazilian diet (e.g. rice, beans, meat, variety of vegetables, etc.) and stressed the important role food plays in their children’s learning about Brazilian culture and of preserving their Brazilian identity. Fathers also spoke of the importance of exposing their children to ethnic Brazilian foods from a very young age to help children develop a liking for such foods. As one father explained, ‘A healthy meal for us Brazilians is the typical Brazilian meal – rice, beans, meat, vegetables and such. From my point of view this is like eating healthy and I try to keep a healthy diet for me and for my kids’.

Furthermore, fathers’ discussion of their personal eating habits, as well as their preferences for their children to eat Brazilian foods, revealed their low dietary acculturation, with nearly all fathers reporting that they ate little or no typical American foods (e.g. hamburgers, pizza, etc.). Additionally, several fathers expressed concerns about their children’s eating of typical American foods when away from home. One father reported,

‘Like my wife and me, I know we grew up in Brazil, but our parents also taught us a liking for our foods and for our culture. Living here in the US, far away from our country, we still like them [children] to learn about our culture, we always talk about Brazil and for Brazilians food is very important and I feel we [parents] need to show them [children] at home our culture. So, in our house when we close the door [to our home], it’s like we are in Brazil … the food, the language we speak, the way we live.’

Theme 2: Fathers’ perspectives about child’s eating and food environments

Fathers’ perceive the home food environment as influencing their children’s eating habits

As previously mentioned, fathers’ viewed food as an important opportunity for their children to learn about the Brazilian culture. Some fathers explained that the home food environment would be the only place where their children would be exposed to Brazilian foods. Furthermore, fathers felt it was important that healthy and traditional Brazilian foods were available and accessible at home for their children. Fathers also spoke of the importance of limiting ‘junk’ (‘porcaria’, ‘bobagem’ – e.g., sweets, candy, etc.) and fast foods (e.g. hamburgers, chips, French fries, etc.), and several noted that it is important that neither they nor their child drink soda (soft drinks). In this context, some fathers mentioned avoiding ‘junk’ food (e.g. sweets, chips, soda, etc.) at home to limit their children’s consumption of such foods. Fathers felt that if children had easy access to unhealthy food options at home, it may lead to them eating too much of these types of foods and developing unhealthy eating habits. One father explained, ‘My son loves to eat chips and cookies, so we don’t buy these foods very often because we know that if we have these types of foods in the house he will eat until it’s all gone’.

Nevertheless, some fathers felt that it is not realistic to expect children not to eat some unhealthy foods once in a while. In addition, a few fathers felt it is difficult not to have these types of foods at home, and cited special occasions (birthdays and family parties) and older siblings as the main reasons for having unhealthy foods at home. One father reported, ‘They are kids and every kid likes to eat candy and cookies and you can’t always say no. So, once in a while we let them eat [junk food]’.

Across all interviews, fathers also spoke about the importance of having family meals. Fathers viewed this time as an important part of daily family life as it provided an opportunity for children to observe and learn from adults about healthy eating habits. Nonetheless, most fathers mentioned that conflicting work schedules prevented their families from eating together on most weekdays. Many fathers explained that on weekdays their children, especially young children, sometimes ate before the whole family, and were often fed by a parent or caregiver due to conflicting work schedules and family obligations (e.g. activities for older children, church events, etc.). One father explained, ‘Here [the USA] it’s not possible to have family lunch given that we work so far from home, have [parents] different working schedules, and the kids are in school all day long. So, we try to have dinners together on a regular basis … We cook Brazilian meals and I think when they [kids] see us eating these foods regularly they learn and get used to eating our typical Brazilian foods … It’s very important for them [children] to learn [eating habits] from us, parents’.

The majority of fathers reported having family rules such as not watching television during meals, and not allowing electronics at the table. For example, one father reported, ‘We have a rule at our house that he [son] cannot watch TV or use his iPad during meals. But sometimes when we do not eat in the kitchen, the television is close and sometimes he [son] wants to eat watching the television or the iPad, but we always take away’.

Family members influence preschool-aged children’s eating habits

Several fathers mentioned that their older children influenced their preschool-aged children’s eating habits. Some fathers spoke of their school-aged children being exposed to unhealthy foods away from home. As one father reported,

‘The older one [child] goes to school and he’s learning to eat the foods that the other kids eat. He likes foods that we [parents] are not used to because we did not grow up eating these foods. So, the little one who is not in school sees his brother asking for foods like chicken nuggets, mac and cheese, you know, the American foods, and he also asks for. He likes and eats the foods the older one eats’.

More than one-third of fathers reported that older relatives, especially grandmothers who cared for their young children while the parents were at work, influenced their young children’s eating behaviours. Fathers had mixed feelings about this. Some fathers credited grandmothers with introducing their children to the traditional Brazilian diet and were happy to have their children ‘learn to eat the way they grew up’. In contrast, other fathers reported that sometimes the beliefs and practices of the grandmothers differed from theirs. For example, some fathers spoke of grandmothers offering children unhealthy foods as treats, giving in to children’s demands, etc., and that this created tension between them and grandmothers or older relatives. As one father reported,

‘My mother-in-law lives with us and sometimes my wife and her don’t always agree about everything. She’s older and has her own way of doing things. But we are just happy she is here and helping us raise our kids the way we were raised in Brazil; with the foods we grew up eating, and with our [Brazilian] customs.’

Increased access and availability of unhealthy foods

Although fathers reported a preference for family and home-cooked meals, several spoke of eating away from home, with most reporting that they preferred eating out at ethnic Brazilian restaurants. Nonetheless, fathers felt that children ate ‘less healthy food choices’ (e.g. pizza, hamburgers and fries, etc.) when eating out.

Moreover, nearly all fathers reported that their children are exposed to and consumed these types of foods away from home (i.e. day-care, schools, friend’s houses), and that this happens more often as children get older. Some fathers mentioned being attentive to their children’s access to unhealthy foods, and trying to limit their consumption of such foods away from home. As one father reported, ‘It’s easy to take the kids to a fast food restaurant and every now and again we take them to McDonald’s or a pizzeria … My wife and I don’t really like to eat these fast foods, but the kids love it. So sometimes we take them. It’s not super healthy, but every so often it’s not so bad’.

Theme 3: Fathers’ perceived role in child’s eating: modelling, responsibility and involvement

All fathers spoke of the importance of parents being good role models. Fathers articulated that they felt it is their parental responsibility to set a good example and eat a healthy diet. The majority of fathers viewed themselves and their child’s mother as their young children’s primary role models for healthful eating. As one father reported, ‘As a parent, we need to set an example for our children. If they see us eating healthy foods – rice, beans, vegetables, meat, they [children] will want to do the same. As parents we need to set a good example. So, if I tell my children that they cannot have Coca-Cola, I shouldn’t drink it either. We need to set a good example and be a good role model’.

Brazilian cultural norms, such as prevailing gender roles that expect the mother to be the primary child caregiver and to be in charge of household chores, emerged as important influences on fathers’ perspectives of child’s eating and feeding practices. Although most fathers mentioned being involved in feeding their preschool-aged child, the majority reported that their children’s mothers were the primary decision-makers when it comes to what their children eat. Fathers felt it was natural for mothers to be more closely involved with children’s eating and feeding, especially when their children are young. Nevertheless, fathers felt that they were much more involved in their child’s eating and feeding than their own fathers were, or extended family members and friends in Brazil are. Several fathers reported they needed to be more involved in and supportive of their wives/partners as they were raising their children away from an extended family and their home country. As one father reported, ‘Here [USA] we don’t have a lot of family around to help us. So, I help [at home] as much as I can with the children. The days that I get home earlier from work than my wife, I am the one who pick the children up from school and day care and give them something to eat’.

Still, fathers felt that they mostly agreed with their wives/partners about what their child should eat, and often engaged in decisions made regarding family food practices and child’s eating and feeding. A few fathers, however, spoke about defaulting to mothers to make the final decisions about child’s feeding practices, as they wanted to avoid conflicts about what their child was fed and ate (e.g. what child ate, how much, etc.). As one father explained, ‘Like my wife is the main person in charge of the household and the cooking. I try to help, but it’s not like I really know how to cook. She’s really good and she takes care of everything; our meals, the children’.

Theme 4: Fathers’ feeding practices

Several fathers spoke of their children’s preference for certain foods, dislike of new foods and being ‘picky eaters’ that affected their children’s eating habits. For example, one father mentioned, ‘Sometimes the only way we can get her [daughter] to finish all her food is by telling her that she will have ice cream if she eats everything. She [daughter] can be really picky and she’s so skinny we want to make sure she eats’. Moreover, a few fathers mentioned that they use electronics for entertainment and to distract their children who are ‘difficult eaters’ or ‘picky eaters’ while being spoon-fed.

Some fathers mentioned that their perception of their child’s weight status influences their feeding practices. A few fathers reported that they and their children’ mothers sometimes allowed children to eat foods that are not considered healthy (e.g. chicken nuggets, macaroni and cheese, pizza, sweets, ice cream, etc.) because they were concerned that their child was not eating enough. In contrast, some fathers reported monitoring their child’s food consumption and intake to make sure they did not eat ‘too much’ unhealthy foods. As one father said,

‘My son loves eating junk food. If we left it for him to decide he would eat those colourful cereals, chips, chicken nuggets, and apple juice. So, we are always controlling and watching what he eats to make sure that he eats some healthy food too like rice, beans, chicken … It’s a constant struggle in our household dealing with his feeding’.

Fathers’ personal experiences with food insecurity while growing up in Brazil shaped fathers’ feeding practices and their views of the importance of making sure that children eat a bountiful diet and the ‘right amount’. Fathers felt it is their responsibility as a parent to provide enough food for their families, and the majority spoke with gratitude of being able to afford large homemade family meals. For example, one father mentioned, ‘Food is something that we value having plenty of. I know because I experienced not having enough to eat in my childhood, so what I experienced as a child I do not want my son, my wife, you know all of us to have to experience. So food is really important for me’. In addition, several fathers described feeding practices such as spoon-feeding (‘dar na boca’) young children to ensure their child ate ‘enough’. One father reported, ‘We encourage with typical incentives and games. Like, using the spoon as a little airplane. “Look at the plane coming”. Or, something like, talking about the food being powerful, things like, “You will get stronger like a Superman”’.

The majority of fathers reported using food such as sweets, deserts and soda to control child’s behaviours (e.g. reward for good behaviour, etc.). Fathers felt that food rewards and other incentives (e.g. screen time) were acceptable when used to help or ensure healthy eating (e.g. eat all food served, eat vegetables, etc.), or to award child’s good behaviour.

Moreover, several fathers spoke of sometimes acquiescing to their young children’s demands for sweets, deserts, soda, etc. The majority of fathers appeared to accept that eating these foods is part of childhood (straight translation ‘being a child’). As one father articulated, ‘We try to make sure they don’t eat junk food. Like we know it’s not good for their health, but they are children, and like other children they like to eat candy, cookies and you can’t always say no’.

Theme 5: Day-care arrangements influence children’s eating habits

Fathers whose preschool-aged children attended day-care reported that their child’s caregiver influenced their children’s eating habits. They also reported a preference for family childcare homes run by Brazilians, and that they liked their children being cared for by fellow Brazilians due to their common culture and child-rearing practices, including diet and child’s feeding practices. Nevertheless, a few fathers mentioned that sometimes their preschool-aged child consumed foods at day-care that they did not think were healthy. For example, one father reported,

‘She [daughter] goes to a family day care and we like that the provider is also Brazilian, but sometimes my wife gets upset that she [daughter] comes home saying she ate sweets at the family day care. My wife can get upset, but for the most part the provider is really good, but sometimes we don’t agree with all she does’.

Theme 6: Fathers’ interest in participating in intervention to promote child’s healthy eating habits

When asked about their interest in participating in interventions to promote healthy eating habits for their young children, all but one father expressed interest in learning more about child’s eating and feeding and were receptive to participating in parenting and family-based interventions to promote early child health behaviours, including healthy eating. As one father said,

‘As a parent you want to do the right thing, we want the best for our children, right? I believe that we are always learning and it’s important to want learn more. That’s always good. So, I would be interested and would participate if a programme or a class was offered for fathers’.

Discussion

The current study adds to the dearth of research on immigrant fathers’ role and involvement in child’s feeding by exploring the perspectives and feeding practices of Brazilian immigrant fathers relating to their preschool-aged children. Findings indicate that factors across multiple levels of the socio-ecological model and social contextual model, including intrapersonal, interpersonal, environmental and organisational levels, influence fathers’ perceptions of healthy eating and their parenting feeding practices.

At the intrapersonal level, findings showed that Brazilian immigrant fathers who participated in the current study believed in the importance of healthy eating. Fathers’ cultural ethnic background and experiences growing up in Brazil influenced their views of what constitutes healthy foods and healthful eating for themselves and their children, with all fathers equating the traditional Brazilian diet with healthy eating. Furthermore, cultural beliefs were evident in fathers’ descriptions of family meals and their feeding practices, with fathers’ preferences for typical Brazilian foods influencing the home food environment. These findings are consistent with prior research with other immigrant groups, including Latino fathers and mothers, that showed cultural influences on family’s diet, parenting feeding practices and children’s eating behaviours(Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney13–Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty17,Reference Davis, Cole and Blake19,Reference Snethen, Hewitt and Petering20,Reference Turner, Navuluri and Winkler23) .

In addition, fathers’ experience with food insecurity growing up in Brazil appeared to shape their views of and beliefs about their children’s eating habits and feeding strategies. For example, fathers wanted to ensure that they had plenty of food at home and that their children ate a bountiful diet. Previous research has documented the association between food insecurity and risk of child obesity, and suggests that this association may be mediated by parental feeding beliefs and practices(Reference Orr, Ben-Davies and Ravanbakht61,Reference Gross, Mendelsohn and Fierman62) . Moreover, consistent with prior research, fathers in the current study perceived themselves as being role models and that it was their parental responsibility to ensure their children ate healthfully(Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney14,Reference Grubb, Salemi and Gonzalez18,Reference Davis, Cole and Blake19,Reference Lora, Cheney and Branscum21,Reference Turner, Navuluri and Winkler23,Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43) . Nevertheless, they also reported personal and cultural beliefs of prevailing gender roles with mothers seen as the main caretaker and being responsible for child’s feeding(Reference Lindsay, Sussner and Greaney14,Reference Grubb, Salemi and Gonzalez18,Reference Davis, Cole and Blake19,Reference Lora, Cheney and Branscum21,Reference Turner, Navuluri and Winkler23,Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43) .

In addition, similar to research with other Latino fathers and mothers, the present study findings also indicate that fathers engaged in permissive feeding and acquiesced to children’s food demands, which influenced their children’s eating behaviours(Reference Grubb, Salemi and Gonzalez18,Reference Lora, Cheney and Branscum21,Reference Turner, Navuluri and Winkler23,Reference Lindsay, Wallington and Muñoz39) . Taken together, these findings suggest the importance of accounting for personal, cultural and psychosocial factors such as gender roles, family values, past food insecurity, etc., when designing parenting and family-based interventions to promote healthy parental feeding practices and child’s eating(Reference Gauthier and Gance-Cleveland12,Reference Pineros-Leano, Tabb and Liechty17,Reference Orr, Ben-Davies and Ravanbakht61–Reference Horodynski, Brophy-Herb and Martoccio63) .

At the interpersonal level, study findings found that fathers’ perceptions of the mother as the primary child and household caretaker influenced fathers’ feeding practices and their children’s eating. In addition, findings also indicated the influence of extended family members (e.g. older siblings, grandmothers) on preschool-aged children’s eating. These findings concur with previous studies conducted with other groups of Latino fathers and mothers(Reference Turner, Navuluri and Winkler23,Reference Parada, Ayala and Horton40–Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43) . For example, previous studies indicated that despite fathers’ influences and involvement in child’s feeding, both Latino fathers and mothers often viewed mothers as having a more direct role in child’s feeding(Reference Evans, Chow and Jennings16,Reference Grubb, Salemi and Gonzalez18,Reference Snethen, Hewitt and Petering20,Reference Lora, Cheney and Branscum21,Reference Turner, Navuluri and Winkler23) . Previous studies also pointed out the influences of the larger family context on children’s feeding, including the role of other family members such as siblings and grandparents(Reference Davis, Cole and Blake19–Reference Lora, Cheney and Branscum21,Reference Turner, Navuluri and Winkler23) .

Furthermore, an important finding of the current study is the difference in the levels of acculturation between fathers and their preschool-aged children that was measured both quantitatively (Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics scores) and qualitatively (fathers’ descriptions). Fathers were found to have low acculturation levels, while their preschool-aged children had high acculturation levels. Previous research has found that fathers’ perspectives and practices relating to their feeding practices and their children’s eating behaviours are associated with their level of acculturation(Reference Lindsay, Wallington and Greaney25,Reference Batis, Hernandez-Barrera and Barquera64–Reference Pérez-Escamilla and Putnik66) . These findings are important and supported by prior research that suggests that the development of family interventions should accommodate cultural preferences and values (e.g. familismo, gender roles, primary language, different intergenerational acculturation levels, etc.) of the target population(Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43,Reference Pérez-Escamilla and Putnik66–Reference Quick, Martin-Biggers and Povis68) .

Fathers who participated in the current study also identified environmental factors such as exposure to a different food environment and increased access to and availability of unhealthy foods as influencing their preschool-aged children’s eating(Reference Grubb, Salemi and Gonzalez18,Reference Turner, Navuluri and Winkler23,Reference Penilla, Tschann and Sanchez-Vaznaugh67) . Study findings showed that the exposure to a new food environment in the USA coupled with families’ competing demands of increased work obligations, conflicting schedules and the pressures of living in a new country, affected families’ eating routines and parental feeding practices. These findings concur with previous studies with other low-income, minority and immigrant groups that have determined the influence of the larger food environment on child’s eating and parental feeding practices that are associated with an increased risk of overweight and obesity(Reference Colón-Ramos, Monge-Rojas and Cremm15,Reference Turner, Navuluri and Winkler23,Reference Penilla, Tschann and Sanchez-Vaznaugh67–Reference Berge, Trofholz and Tate70) .

At the organisational level, fathers identified child care as influencing their children’s eating behaviours and feeding. This finding is in agreement with previous research(Reference Benjamin, Haines and Ball71–Reference Francis, Shodeinde and Black73). In fact, recent research suggests that childcare providers may be as influential as parents in shaping food preferences of young children, as children’s increased attendance and hours spent in these settings make these settings influential in the development and maintenance of children’s early healthy eating behaviours(Reference Lindsay, Greaney and Wallington72,Reference Francis, Shodeinde and Black73) . Our findings suggest the importance of addressing multiple environments that influence young children’s eating behaviours, including the home environment and childcare settings(Reference Benjamin, Haines and Ball71–Reference Mazarello Paes, Ong and Lakshman74).

Study findings also indicate that Brazilian fathers who participated in the current study face several contextual factors that influence the day-to-day lives of Brazilian immigrant families (e.g. family constraints such as working hours and conflicting working schedules, multiple competing demands, etc.). These findings are important and should be considered in the planning and logistics of child nutrition and health promotion interventions designed to include Brazilian immigrant fathers’ participation.

Finally, an important finding of the current study is that most fathers were receptive to learning more about child’s feeding, and their interest in participating in parenting and family-based interventions aimed at promoting their children’s healthy eating behaviours. When asked if they would like to add anything before the interview ended, nearly all fathers said they were happy to talk about their feeding practices and their children’s eating behaviours, and wanted to learn more and do ‘what’s right’ for their children. This finding is supported by prior research(Reference Khandpur, Blaine and Fisher29,Reference Jansen, Harris and Daniels75–Reference Davison, Charles and Khandpur77) , and suggests that some fathers are receptive to participating in family interventions aimed at promoting healthy eating behaviours of preschool-aged children in Brazilian immigrant families. Previous studies have documented the underrepresentation of fathers in child nutrition and health promotion interventions, suggesting the need for future research to recruit diverse samples of fathers(Reference Khandpur, Blaine and Fisher29). Furthermore, in a recent study with a diverse sample of over 300 fathers, Davison et al. (Reference Davison, Charles and Khandpur77) found that the vast majority (approximately 80 %) reported that fathers are underrepresented in research because they have not been asked to participate. These studies indicate the need for interventions designed to promote children’s healthy eating and healthy weight status to include fathers, and especially minority fathers(Reference Khandpur, Blaine and Fisher29,Reference Davison, Charles and Khandpur77,Reference Tan, Domoff and Pesch78) .

Although more research is needed, findings from this exploratory qualitative study point to some important targets that should be considered in family interventions designed to promote healthy parental feeding practices in Brazilian immigrant families living in the USA. For example, interventions designed to promote healthful parenting feeding practices and children’s healthy eating should consider the roles of both fathers and mothers. Interventions also should address intrapersonal (e.g. parental beliefs, parents’ eating habits) and interpersonal factors (e.g. parents’ feeding styles and practices, role of older siblings and grandmothers) of the shared home environment(Reference Sorensen, Emmons and Hunt52–Reference Peters and Halcomb55).

Furthermore, fathers who participated in the current study reported several social contextual factors and logistical barriers affecting their and their families’ daily lives, such as parents’ time constraints, long working hours, conflicting work schedules, multiple competing family demands, etc., which should be considered when developing family interventions (e.g. mode of delivery, length, time commitment, etc.) for Brazilian immigrant families. For example, these findings coupled with prior research suggest that family interventions involving Brazilian immigrant fathers might be more acceptable and feasible if requiring small time commitment and clearly stating the benefits for fathers and their families(Reference Parada, Ayala and Horton40,Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43,Reference Penilla, Tschann and Sanchez-Vaznaugh67,Reference Lindsay, Greaney and Wallington72–Reference Jansen, Harris and Daniels75) . In addition, family interventions should also consider offering fathers a flexible means of participation, such as online training modules and other activities that can be completed at home via the Internet (desktop computer or mobile devices) when fathers have available time(Reference O’Connor, Perez and Garcia43,Reference Jansen, Harris and Daniels75,Reference Davison, Charles and Khandpur77) .

Findings of the current study should be viewed in light of some limitations. This was an exploratory study with a purposive sample of Brazilian immigrant fathers living in Massachusetts who may have an increased interest in the topic of the study. The small convenience sample, although appropriate for a qualitative exploratory study, might lead to biases in study’s findings, especially as it relates to fathers’ receptivity and interest in participating in future interventions, which applies only to the small group of fathers who participated in the study.

Future research is needed to quantify Brazilian immigrant fathers’ feeding styles and practices, and solicit and include fathers’ inputs when designing child nutrition and health promotion interventions. Future research should also assess fathers’ preferences for content, degree of participation and means of delivery of culturally sensitive family interventions designed to meet the specific needs of this ethnic group. In addition, future research should also consider including Brazilian immigrant fathers from other communities across the USA.

Conclusions

Using a socio-ecological approach, this exploratory qualitative study presents new information on multiple factors that interact across multiple levels of influence, including intrapersonal, interpersonal, environmental and organisational levels, to shape fathers’ beliefs about their children’s eating and their parenting feeding practices. This information is important in understanding paternal influences on children’s eating behaviours, and helps provide a more complete picture of Brazilian immigrant parents’ perspectives and practices relating to child’s feeding and their preschool-aged children’s eating behaviours. Given the central role of the family in the Brazilian culture, the development of effective family interventions targeting the promotion of healthful parenting feeding practices, child’s healthy eating and healthy weight should take into consideration the role of fathers.

Findings showed fathers’ awareness of the importance of healthy eating for their children, their role in influencing their children’s eating through their influence on what’s cooked and served for meals, their role modelling, their permissive feeding styles, etc. Moreover, findings identified influences within the immediate home environment (e.g. family function and routines, older siblings, grandparents, etc.), as well as the out-of-family environment (larger food environments, child day-care, etc.) that affect fathers’ feeding practices and preschool-aged children’s eating behaviours. Moreover, fathers who participated in the current study reported several social contextual factors (e.g. time pressures, working schedule, competing family demands, etc.) that impact their and their families’ day-to-day lives and that have implications on the development of interventions targeting Brazilian immigrant families.

Finally, although limited by the small convenience sample, nearly all fathers who participated in the current study showed interest and receptivity to participating in parenting and family interventions aimed at promoting their children’s healthy eating. This finding is important and should be further explored and considered in the planning of future studies and the development of family interventions aimed at promoting healthy eating and healthy weight status of preschool-aged children in Brazilian immigrant families.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We thank the fathers who participated in the study as well as the faith- and community-based agencies in Massachusetts, USA, for support in recruitment efforts. Financial support: The current study was funded by the Aetna Foundation Inc. (A.C.L., PI). At the time of the current study, G.V.B.V. was supported by a scholarship (Doctoral Program Abroad) from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil. Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Authorship: The following co-authors contributed to the work: A.C.L. designed the study, oversaw data collection, participated in data analysis, led manuscript preparation and review. G.V.B.V. participated in data collection, interpretation of findings and manuscript preparation and review. C.A.M.A. participated in data analysis, interpretation of findings and manuscript preparation and review. A.D.S.M.A. participated in data collection and manuscript review. M.M.T.M. participated in interpretation of findings and manuscript preparation and review. M.H.H. participated in interpretation of findings and manuscript preparation and review. M.L.G. contributed to study design, led data analysis, participated in interpretation of findings, and manuscript preparation and review. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Massachusetts Boston’s Internal Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Verbal consent for the audio-recording of individual interview was witnessed and formally recorded.