Introduction and Goal of the Article

One of the most commonly used clichés in border studies is the metaphor of borders as “scars caused by history.” Many borders are the sites of historical conflicts between rival neighbors in Europe. Cross-border cooperation (CBC) has helped to eliminate the consequences of these conflicts, and it has contributed to understanding the border as a (development) opportunity (Decoville et al. Reference Decoville, Durand, Sohn and Walther2013). Divided towns are often the places of former conflict, where the CBC has helped to eliminate the negative barrier effect of the border (Böhm and Drápela Reference Böhm and Drápela2017).

The studied townsFootnote 1 Cieszyn and Český Těšín lie in the heart of the historical Těšín/Cieszyn Duchy (see figure 1), which existed from the end of the 13th century until 1918 (Korbelářová and Žáček Reference Korbelářová and Žáček2008). They were divided after an armed conflict between Czechoslovakia and Poland after the end of World War I. After an international arbitrage, the town and the whole region were divided, and the Olza River became a national border (Böhm and Drápela Reference Böhm and Drápela2017). Mainly Poles felt (and some still do) that this division was unfair because most of the inhabitants of the territory obtained by Czechoslovakia have self-identified as Poles. One hundred years later, approximately one-fifth of the entire population living in the Czech part of the territory uses Polish as its mother tongue.

Figure 1. Localization of the Těšín/Cieszyn Region.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on OpenStreetMaps.

Cross-border contacts were maintained in the region after its division. Separated families were also able to meet during the communist period, when the border crossing between Poland and Czechoslovakia was partially complicated. In contrast to the rest of the Czech-Polish border, from where the original majority German-speaking population was expelled after World War II (Dołzbłasz Reference Dołzbłasz and Hall2017), there was no significant population change in the Cieszyn/Těšín Region.

After the end of communism in Eastern Europe, the two towns started to cooperate more closely. In 1993, regional cooperation between both Cieszyn and Český Těšín was formalized by means of their mutual agreement. Both parts of the divided town hold joint meetings of municipal assemblies annually and cooperate closely. Their successful cooperation contributed to the establishment of the Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia Euroregion in 1998. The Euroregion covers an area of 1,400 km2 with 630,000 people (of whom 360,000 live in the Czech part and 270,000 in the Polish part). Cooperation of the divided town is vital for the operations of the Euroregion (Boháč Reference Boháč2017; Böhm Reference Böhm2021, 144).

After the EU enlargement, the EU funds provided a unique financial incentive for the development of the divided town. The new joint leisure-time cross-border infrastructure and relaxation zones in both parts of the divided town were connected by a new footbridge for pedestrians and cyclists. This helped to initiate a number of common Czech-Polish cultural and sporting events that use this infrastructure. The organization of joint theater and film festivals or sporting events, such as the regular joint cross-border jogging, has contributed to the emergence of a local cross-border civic society and the feeling of cross-borderness. This was enabled also thanks to the absence of the language barrier in the divided towns, because the local dialect is actively used, or at least understood on both sides of the border (Böhm Reference Böhm2018, 83).

In 2007, the Schengen area enlargement helped to further strengthen cross-border ties in the divided town. Poles began to purchase cheaper properties on the Czech side and settle there. Students from the Polish side of the divided town began to attend schools on the Czech side on a larger scale – there are nursery, elementary, and secondary schools with Polish as a language of instruction in the Czech part of the Euroregion, given the high presence of Polish minority in this region. Cross-border commuting started to occur more and more frequently because the Poles started to take advantage of the higher earnings and available job vacancies on the Czech side of the border (Böhm and Opioła Reference Böhm and Opioła2019). One hundred years after the division of the town, Cieszyn-Český Těšín was perceived as one of the model examples of successful cross-border cooperation (Boháč Reference Boháč2017) in the “new EU,” where the border is not a barrier between communities anymore. However, this image was significantly damaged when free border crossing was restricted as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The following months helped to highlight the principal features on which mutual cooperation is based in the divided town. The pandemic showed that “…people living in border areas are re-shaping the European narrative of borders and especially they are the agents who make the European story through their daily life” (Medeiros et al. Reference Medeiros, Ramíréz, Ocskay and Peyrony2021, 979).

The article asks whether the divided town can also be considered a joint “living space” in the shadow of the pandemic. It evaluates the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on three key dimensions of cross-border integration in the divided town: cross-border flows, cross-border structures/institutions, and the ideational dimension of cross-border togetherness. The added value of this research is an attempt to prove that a divided town in the “new EU,” where the level of cross-border integration is generally considered lower than the one in the “EU core” (Eurobarometer 2015; Durand and Decoville Reference Durand and Decoville2019, 174), can surpass those expectations. Moreover, the studied territory is shared by Poland and Czechia, which are considered to be enfants terribles of European integration. Consequently, the use of argumentation based on the “European values” against the border closures in Cieszyn-Český Těšín was examined.

The article is organized as follows: the next section provides an overview of the main research directions in border studies, with attention dedicated to the divided cities’ scholarship. The third section outlines the methodology used and the main materials analyzed in the article. The fourth section presents and discusses the research findings. The final section draws conclusions and highlights the principal elements of cross-border integration of the divided town Cieszyn-Český Těšín.

Theoretical Framework to Study Divided Cities/Towns

Cross-Border Cooperation Scholarship

Cross-border cooperation (CBC) has become a popular research topic for many social scientists in the last years. The current border studies constitute a specific interdisciplinary field where sociology meets geography, political sciences, cultural sciences, legal and administrative sciences, economy, and history (Brunet-Jailly Reference Brunet-Jailly2005). CBC has been realized by public actors at the subnational level. It has contributed to the changed border function from a closed filter to an open border of meeting and opportunity. From a very preliminary stage, it has been understood as a micro–foreign policy/paradiplomacy (Duchacek Reference Duchacek, Michelmann and Soldatos1990), deliberately differentiated from other forms of cooperation that had been intensified at the nation-state level across Europe after World War II (Beck Reference Beck2019). The earliest beginnings of such cooperation between directly adjoining regions of neighboring states date back to the 1950s. German-Dutch Euroregio, or Regio Basiliensis – the tri-border region between Germany, France, and Switzerland – can be mentioned here (Beck Reference Beck2019, 14).

At the central state level, CBC has officially been recognized and supported as of the 1970s, given that intergovernmental agreements and mixed government commissions were established. In the second half of the 1980s, the European Communities took up the issue of CBC and made it a part of its regional policy. European funding policy has contributed to an enduring upgrading and differentiation of cross-border policies. Since 1990, the EU’s Cohesion Policy has supported CBC with the Interreg initiative, with a total of €30 billion (Scott Reference Scott, Scott and Pete2016; Beck Reference Beck2019). Residents of border regions have been encouraged to exploit free movement and to actively engage in creating cross-border living spaces, where daily life activities such as residence, work, education, shopping, and other leisure activities span borders (Klatt Reference Klatt2020). For a long time, researching CBC has had a very “Western” bias, given the longer period of institutionalized cooperation in the “old EU” (Beck Reference Beck2019). The EU eastern enlargements offered this possibility also for the citizens of border regions from the new Member States.

Consequently, borders in the “new EU” have also become a subject of scholarly attention since then, which has not excluded the Czech-Polish territory. Lewkowicz (Reference Lewkowicz2019) sees the Polish-Czech border as one of the better integrated ones, from the comparative perspective of all Polish borders. Dołzbłasz (Reference Dołzbłasz2015, Reference Dołzbłasz and Hall2017), Böhm and Šmída (Reference Böhm and Šmída2019), and Vaishar et al. (Reference Vaishar, Dvořák, Hubačíková, Nosková, Nováková and Zapletalová2011) underscored the importance of cross-border tourism for mutual CBC initiatives. The social and cultural dimensions of the Polish-Czech borderland were analyzed inter alia in the studies of Śliz and Szczepański (Reference Śliz and Szczepański2016), Dębicki (Reference Dębicki2010), Czepil and Opioła (Reference Czepil and Opioła2013).

According to many scholars, Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia, with its Polish minority living on the Czech side, is the most integrated part of the borderland with a high volume of multiple cross-border flows (Pásztó et al. Reference Pásztó, Macků, Burian, Pánek and Tuček2019; Böhm and Opioła Reference Böhm and Opioła2019), and where CBC contributed to mutual post-conflict reconciliation (Böhm and Drápela Reference Böhm and Drápela2017; Wróblewski and Kasperek Reference Wróblewski and Kasperek2019).

In academic discussions on cross-border integration, border scholars observe its higher level in the “EU core.” In one of the most recent articles on cross-border integration, Durand and Decoville (Reference Durand and Decoville2019) conducted a multidimensional analysis of cross-border integration along the EU internal borders. It was based on the flow approach (van Houtum Reference van Houtum2000), which analyzes cross-border practices (the functional dimension of cross-border integration), the level of mutual social trust between border populations (the ideational dimension, based on the Eurobarometer [2015]), and the involvement of stakeholders in cross-border cooperation projects (the institutional dimension). They came to the conclusion that the cooperating entities in the new EU can be characterized by low mutual social trust between populations living on either side of the border and low interpenetration of neighboring border territories by the populations (few cross-border activities are observed). Their conclusions are in line with findings of the official documents of the European Commission (2016) on removing cross-border obstacles in border regions and on the number of cross-border public services in the EU (ESPON 2018).

Divided Cities/Towns

Historically, there have been situations – mostly wars and subsequent conventions – when the state border has divided one settlement into two separate units, especially in ethnically heterogeneous regions. The Versailles System, defining borders between former parts of Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Potsdam Conference, outlining Europe’s geography after World War II, caused the emergence of the highest number of divided towns/cities in current Europe. Those newly set borderlines changed the positions of divided towns from often centrally located spaces to the periphery, with difficult transport, economic, and ethnic situations (Boháč Reference Boháč2017, Dębicki and Tamaska Reference Dębicki and Tamáska2014).

Currently, there are 60 divided towns along borders in Europe (Dębicki and Tamáska Reference Dębicki and Tamáska2014; Buursink Reference Buursink1994; Ehlers Reference Ehlers2001; Joenniemi and Sergunin Reference Joenniemi and Sergunin2011; Waack Reference Waack2000; Schultz Reference Schultz2003). They are often divided by a river; consequently, they are also referred to as bridge cities/towns. Those divisions have often resulted in national minorities having their kin-states just across the river. The divided cities often have a name in each of the involved languages that is also comprehensible to people on the opposite side of the border. Examples are Komárno/Komárom (Slovakia/Hungary), Görlitz/Zgorzelec (Germany/Poland), or Cieszyn/Český Těšín. The complicated history of Central Europe has even led to the reunifications and, later on, repeated divisions of bridge towns. This was the case of Cieszyn/Český Těšín and Komárom/Komárno.

Divided cities are sometimes confused with partner cities that strive to build cultural connections between their organizations and individuals – although in many cases, including Cieszyn/Český Těšín, the partner is the other part of a divided town. Given the geographical proximity of cities, this option makes sense and substantially eases fundraising for the joint projects (Boháč Reference Boháč2017).

It was mainly the European integration that helped divided towns in Europe overcome the traditional realistic paradigm, eliminate the negative consequences of the location on the borderline, and become one of the integration symbols (Zumbusch and Scherer Reference Zumbusch, Scherer and Beck2019, 32). The divisive borders have gradually eroded, and consequently, various substate entities – including cities – have been able to establish relations of their own. This opened the way for cities to aspire to togetherness breaching previous divides (Joenniemi and Sergunin Reference Joenniemi and Sergunin2011, 25). They have been able to participate in the endeavors of reconciliation, which was mainly visible and symbolic across the French-German border (cf. Wagner Reference Wagner1995).

There is no single conclusion about the level of cross-border integrations in divided towns. Dębicki and Tamáska (Reference Dębicki and Tamáska2014) claimed that interactions are reduced mostly to nonpersonal actions: shopping or taking a walk in the other part of a twin town. They argue that divided twin towns are far from being integrated and “reunited” urban structures. This is because the borderlines and frontier zones of the present urban places more or less overlap with the mental (ethnic and linguistic) zones of their inhabitants, and due to the economic differences in both sections of the twin town. Joenniemi and Sergunin (Reference Joenniemi and Sergunin2011, 128) expressed a different opinion. They argue that “…the twin city concept has enabled several cities to use their location in order to opt for new forms of being and acting. The providing of a new and broader twist to the concept of the twin city and reproducing it in a trans-border context constitutes one specific aspect of an increasingly integrated political landscape.” In some divided towns, we can observe the introduction of joint cross-border public services, as is the case for the cross-border health care in Gmünd/České Velenice in the Austrian-Czech borderland (ESPON 2018; Böhm and Kurowska-Pysz Reference Böhm and Kurowska-Pysz2019).

Joenniemi and Jańczak (Reference Joenniemi and Jańczak2017, 425) underscore that recent decades have also brought about both new forms of twinning and manifestations of cities being “ahead of states.” European integration identified city partnerships that presented themselves as “forerunners of integration.” City pairing is positioned as part of a broader trend of togetherness and unity, albeit with cities being ahead of the states, and as showing the way for other national policies to follow. City twinning is viewed as an agent of change, helping to blur the ordinary distinction between so-called high and low forms of politics.

Kaisto (Reference Kaisto2017, 464) applied a spatial framework, inspired by Lefebvre’s spatial triad (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1974), which distinguishes between “perceived space, conceived space and lived space.” She argues that “individuals are likely to identify with the twin city if their spatial perceptions of and lived experiences in the twin city correspond with the associations they have of the concept” (Kaisto Reference Kaisto2017, 459). She recommends paying more attention to how local citizens understand twin cities as concepts and as spaces for everyday life.

Pandemic-Related CBC Research

Until recently, mainstream border studies focused on studying debordering and analyzed the borderline as a source of opportunities (Decoville et al. Reference Decoville, Durand, Sohn and Walther2013). The recent COVID-19 pandemic outbreak might cause a substantial increase of rebordering processes and a return to nationalist discourse (Medeiros et al. Reference Medeiros, Ramíréz, Ocskay and Peyrony2021; Jańczak Reference Jańczak2020; Böhm Reference Böhm2021) because the pandemic challenged the fundamental freedoms of the EU in a very complex way (Unfried Reference Unfried2020). Its consequences have been negative, primarily in border regions (Klatt Reference Klatt2020). The pandemic showed that although national borders were once thought to be a feature of Europe’s past, the pandemic has underscored how resilient and meaningful they continue to be (Castan Pinos and Radil Reference Castan Pinos and Radil2020). It appears that national states continue to be the basic “social containers” that define the world system (Rufí et al. Reference Rufí, Richard, Feliu and Berzi2020) – even in the EU.

Medeiros et al. (Reference Medeiros, Ramíréz, Ocskay and Peyrony2021) used the term “covidfencing” to explain the systematic closing of national borders to the circulation of people. This covidfencing proves that these perceptions of territorialism enjoy an overwhelming global acceptance, despite the fact that the authors denied that the issue is black and white and understand CBC to be an important element of European integration. However, the reintroduction of physical borders has demonstrated not only the power of national states but also the high level of cross-border integration in certain border regions, especially in divided towns. Jańczak (Reference Jańczak2020), Hennig (Reference Hennig2020), and Opiłowska (Reference Opiłowska2021) analyzed the impact of the pandemic on the German-Polish border, where they observed the high level of cross-border integration, driven mainly by cross-border flows. They also underlined the importance of divided towns in cross-border integration. Hennig (Reference Hennig2020) highlighted the significance of civil society actors in times of crisis, who were able to lobby for a less restrictive border management response and helped to hold bilateral relations together. Böhm (Reference Böhm2020) advised understanding covidfencing as a possible new “fuel” for CBC actors.

Materials and Methodology

First, the theoretical framework for studying cross-border cooperation and divided towns was written. Then, it was necessary to summarize the reactions of border scholars and CBC practitioners to the impacts of pandemic-related covidfencing on the border regions in Europe, especially on the Czech-Polish borderland. Consequently, we conducted a content analysis (see Krippendorff Reference Krippendorff2004 or Neuendorf Reference Neuendorf2017) of those first reactions, covering the period from April 2020 to November 2020. We worked exclusively with papers and oral contributions presented during online conferences held in English, Polish, and Czech. Regarding the e-events, we used the outcomes of the conference panel organized by Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań on May 21, 2020 and the e-meeting “Cross-Border Cooperation in the Age of the Pandemic” organized by the Association of European Border Regions on June 5, 2020.Footnote 2

Then, we organized the work so as to cover three principal aspects of cross-border integration. We analyzed the impacts of pandemic-related restrictions on (1) cross-border flows, (2) cross-border institutions, and (3) the ideational dimension of living in a divided town. We made a content analysis of adopted anti-epidemic measures at the level of the Czech and Polish governments. We also analyzed the responses of the local institutions, which had to comply with the restrictions imposed by the national governments and to respect the specific milieu of the borderland at the same time. Special attention was given to the analysis of Euroregion Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia.

Then, we focused on the coverage of the (ontological) narratives (Somers Reference Somers1994) of the locals on border closure in the divided town. Covering the period from the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020 until the end of 2020, we analyzed the Facebook (FB) groups gathering or followed by the local inhabitants. We worked with the official FB pages of both parts of the divided town, the Euroregion page, local information pages, and community groups pages. Special attention was dedicated to the pages gathering cross-border commuters, NGOs promoting cross-border culture, and FB presentations of the Polish minority living in Czechia. Jointly, we identified up to 42 possibly relevant pages, but we decided to work with the ones with the highest numbers of members/followers.Footnote 3 Then, we went through 126 individual entries – three per page. We planned to have a balance of studied entries in both languages (which was not possible due to the higher number of contributions in the Polish language) and from the gender perspective.

To get an opinion about the public narrative (Kulas Reference Kulas2014), we analyzed 23 media articles covering the consequences of border closures in the east of the Czech-Polish border. We covered both mainstream (including tabloids) and regional media.Footnote 4 We worked with the articles published between March and October 2020. We maintained balance in selecting the respected (printed and online) media as well as tabloids from both parts of the border – despite the fact that Polish media outlets covered this region more than Czech ones.

Institutions promoting cross-border cooperation in both countries use Facebook. For this reason, we decided to look at whether these FB pages target audiences from both parts of the divided town. An eventual positive answer could attest to a rather high ideational dimension of cross-border integration. We foresaw that the higher level of cross-border integration in the studied divided town (in comparison to the rest of the Czech-Polish border) should also be reflected in the higher turnout on their FB pages and in a higher number of these pages per se, but we did not know to what extent. Therefore, we identified the pages of actors in Czech-Polish cross-border cooperation. A set of partial criteria, allowing for the (rough) identification of the engagement of the civic society and other actors in cross-border cooperation in six Czech-Polish Euroregions, was applied. We assessed (1) the number of followers of the page and its eventual increase/decrease after the beginning of the pandemic; (2) the language regime of these pages – the use of both could imply a higher cross-border cooperation intensity; (3) the frequency of posts to judge whether the page is active and regularly (at least on a weekly basis) updated; and (4) the number and nature of FB pages (other than those managed by the Euroregions themselves) focusing on cross-border cooperation in each Euroregion. The result gave us information about an intensive use of cyberspace also in the cross-border context.

The impact of border closures on cross-border flows was chiefly obtained thanks to the findings of an online survey in which 1,519 respondents participated. The questionnaire, based on the Google Forms platform, was prepared in Polish and Czech language variants and was online in November 2020. It contained metrics and 13 single- and multiple-choice questions that asked the inhabitants of the divided town and adjacent border region about the impact of the pandemic-related border closures on their daily lives. The survey was intended to serve multiple purposes, but opinions were gathered primarily for the sake of proposing a set of measures that would prevent the repetition of problems experienced in the spring of 2020 in the event of subsequent border closures. The aim of the survey was to obtain as many responses as possible because the team working on the set of recommendations had to have a high number of interviews in order to have a strong mandate for the proposed set of measures. Thanks to the active promotion of the survey by the local cross-border cooperation stakeholders, NGOs, and local media, the final number of respondents was high.

Overview of the Border Closures in Cieszyn/Český Těšín in the First Half of 2020

Both parts of the divided town experienced the pandemic-related reintroduction of the hard border. Poland reintroduced border control at all internal Schengen land, air, and sea borders from March 15, 2020 to June 12, 2020. Czechia did it at land borders with Germany and Austria and at air borders from March 14, 2020 to June 13, 2020. Because Poland had ceased to allow foreigners into its territory, there was no need for the Czech government to “close” the (Czech-Polish) border. The strictness of the border closures was softened by the fact that cross-border commuters were allowed to cross the border. Because the flow of cross-border commuters is one-way – Poles benefit from the higher salaries and greater availability of jobs in Czechia –cross-border commuting was still possible. This was changed by the decision of the Polish Government (decree 2020/566) to implement an obligatory 14-day quarantine for all people crossing the Polish border. It also applied to cross-border commuters and students, who crossed the border on a daily basis. This quarantine obligation for cross-border commuters and students was abolished on May 4, 2020, also thanks to the endeavors of local politicians (Opioła and Böhm Reference Opioła and Böhm2021).

Despite the fact that June 13, 2020, brought a reintroduction of the borderless regime to the majority of the Czech-Polish border, this was not the case for Cieszyn/Český Těšín. Given the high numbers of COVID-19 occurrences in the coal mines in Polish Silesian Voivodeship, the Czech government prolonged border-crossing restrictions in this part of the border by two weeks. Local politicians jointly raised their voices against this prolongation, as is described in the next section.

Principal Findings

Findings Based on Media and Social Networks Analysis: No Comeback of Nationalism

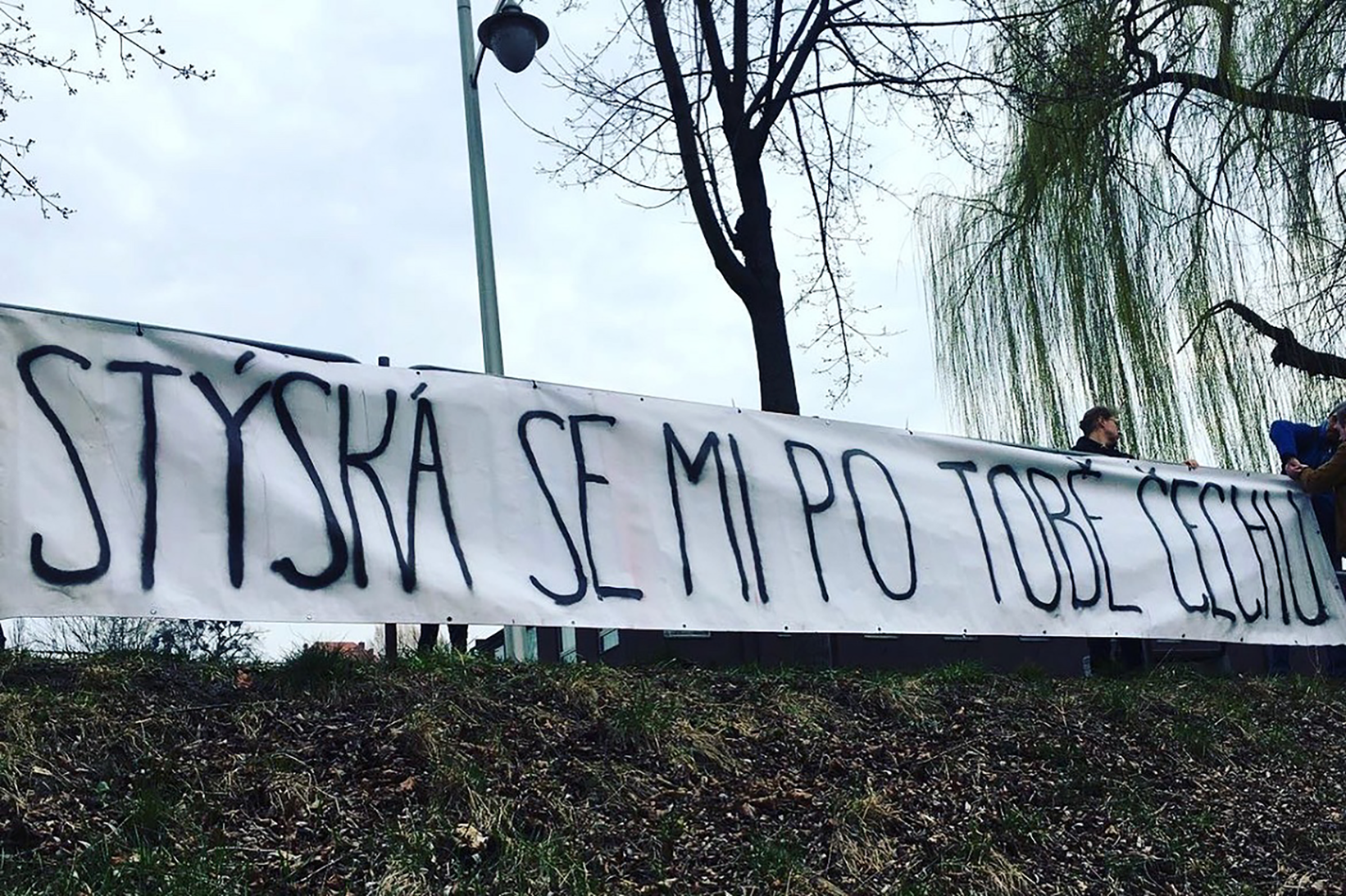

The border closures came as a shock to the locals and suspended many cross-border social practices. On the other hand, it also pointed to the existence of a cross-border civic society in the divided town. The visible manifestation of civic society activity came a week after the reintroduction of border closures, when the Polish activists in the morning and their Czech counterparts in the evening placed banners that read “Stýská se mi po Tobě, Čechu” (I Miss You, Czech) on railings on their side of the border river (see figure 2). Stefan Mańka, initiator of the idea and coauthor of the Polish banner, regretted the “unexpected and suddenly limited contact with Czech friends” (Seznam Zpravy, March 21, 2020) and underscored that he wanted to lift the mood of the locals. He claimed, “A lot of Poles stayed on the Czech side of the border because they profit from the lower living costs or are part of mixed Polish-Czech families. The border-crossing restrictions have negative economic consequences, as the shops in Poland miss their Czech customers. And last but not least, cultural life, which is made up jointly by both Czechs and Poles here, suddenly encountered an unimaginable obstacle – the border” (Seznam Zpravy, March 21, 2020).

Figure 2. Banner: “Stýská se mi po Tobě, Čechu” (I Miss You, Czech).

Source: Reprinted by permission from Stefan Mańka, author of the banner.

In the same vein, the local Czech band Izabel reacted to the situation with their song “Two Banks”(Izabel and Bartnicky 2020). This song, cowritten with Bartnicky, a band from the Polish part of the divided town, calls for the immediate return to normality – the end of the border closure. This rather unknown band experienced major media interest and a high number of YouTube views.Footnote 5 Dominik Folwarczny, the band member who was also responsible for the banner on the Czech side of the river, emphasized that the musicians wanted to please the locals: “Especially for us, the young ones living here at the border, it was natural to jump over the bridge to see our friends, to have fun or to do shopping. We can’t do it now, but we believe the situation will return to normality soon" (Hutník Reference Hutník2020).

These posters and the song attracted substantial media attention – which rarely occurs – from both Polish and Czech media. We found additional articles in the Polish media, which can be attributed to the size of Poland and a certain asymmetry of Czech-Polish relations – that is, Poles declare more interest in their southern neighbors than vice versa (Böhm and Drápela Reference Böhm and Drápela2017). Their discourse described the feelings of the local politicians and local inhabitants, who were surprised by the rebordering, because they consider free border-crossing to be a norm. The local people seemed ready to accept it as a short-term solution to cope with the outbreak of the pandemic, but they would then demand an immediate reopening the border and an end to sudden uncertainty. We have not been able to find any media article that reported about the opposite feelings in the first weeks of the health crisis. On both sides of the border, media coverage reflected the stories of the locals and created the commonly accepted narrative that asked for a return to (borderless) normality. This was shared even by tabloids, which reported about the divided families.

The FB analysis offered a similar picture: the private and public narratives almost overlapped and reinforced each other. FB entries asking for prolongation of the border closure and expressing hostility vis-à-vis the neighbors were extremely rare, and the authors of those that did seem to have similar “hate speech” posts on most of the public issues they commented on.

The local and regional politicians from both sides of the border expressed the same opinions during the first pandemic wave. They declared their support for border region residents by referring to catchphrases such as “united Europe,” “two banks – one city” and “transnational life of borderlanders” – which is exactly the same rhetoric as the one in the German-Polish borderland (Opiłowska Reference Opiłowska2021). The decision of the Polish government to introduce an obligatory 14-day quarantine for everybody arriving in Poland caused sharp rhetoric against the national government and later even led to demonstrations. Local politicians criticized the “top-down imposed” restrictions and demanded the opening of the border for local traffic so as to enable cross-border commuting.

After the introduction of the quarantine, the cross-border commuters started to act publicly and express their demands. They established the Facebook page “The Voice of Cross-Border Commuters in Czechia” to enable the networking of individuals whose primary goal was to end the 14-day quarantine requirement. The posts on social media pointed at the precarious situation and uncertainty of cross-border commuters, and they both highlighted the lack of coordination between both governments and underscored the concerns of Polish cross-border commuters that the decisions of Polish authorities could contradict the Czech ones (Opioła and Böhm Reference Opioła and Böhm2021).

In April 2020, the protests left the virtual space and materialized into demonstrations in both parts of the divided town, demanding softening of the imposed quarantine measures. The protesting (Polish) breadwinners in Czechia, who decided to avoid quarantine obligations, found accommodation and continued working on the Czech side of the river, whereas their families protested on the Polish side of the river (Opioła and Böhm Reference Opioła and Böhm2021). These requirements were partially accepted by the Polish government at the end of April 2020, thanks to a significant intervention by the Euroregion, as demonstrated by the correspondence between its (Polish) secretariat and the prime minister of Poland. Euroregion Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia led the dialogue with the Warsaw government and became an important and successful advocate of the interests of cross-border commuters.

Despite the fact that Polish actors were always first to protest against the border closure in the spring of 2020 (also in the banner exchange, given that the first banner was installed on the Polish side of the border on March 20, 2020, in the morning, and the Czech response came the same day in the evening), local politicians from both sides of the border acted in agreement in their endeavors to soften the consequences of the border closures. This unity was partly disrupted in mid-June 2020, when the president of the (Czech) Moravian-Silesian Region initiated the unilateral prolongation of the border closures in the eastern part of the border, given the high incidence of COVID-19 in the neighboring Silesian Voivodeship. This decision was strongly criticized by local politicians from both sides of the border.

The chairman of the Cieszyn self-administrative district, Mieczysław Szczurek, who contested the decision of Czech authorities, gave a good illustration of the feelings of many people from the Polish part of the divided town: “I am shocked that on the other side of the river there is a legal act that painfully discriminates people living in the Silesian Voivodeship, compared to the rest of the Polish regions…We have been painfully divided and discriminated against by the Prague authorities, only because we live here. I remind our Czech brothers that, in the face of illness, we should help each other, we should support each other, because we all belong to one great European Community. I appeal to the Polish government to offer its support to the inhabitants of Silesian Voivodeship and to start talking to its Czech counterpart until the reopening of borders for all Poles” (Beskidzka24, June 15, 2020). Similar anger could have been observed on social networks, with an important difference: the frustrated inhabitants of the Polish part of the divided town protested against the decision made in Prague by the Czech government, not against their Czech neighbors living on the other side of the river.

The mayors of both parts of the divided town joined in protesting, using somewhat softer vocabulary. "The lives in border area are very different from the ones in national capitals, Warsaw or Prague. We are really one town here," said Gabriela Hřebačková, the mayor of the Czech part of the divided town, referring to the close ties between people on both sides of the border. “The decisions came from the capital and disregarded the local specificities," she said (Głos Ludu, June 16, 2020). Local politicians from both parts of the border along with representatives of the cross-border society initially planned to gather on a border bridge to express their silent protest against the prolongation of border closures. The whole event ended up to be a loud demonstration, attended by the citizens from both parts of the town. The local politicians jointly underscored the European dimension of life in the divided town and criticized the representatives of the central governments of both countries. “Our powerlessness is frustrating,’’ said Bogdan Kasperek, director of the Polish part of the Euroregion, summarizing the feelings of local politicians and borderlanders. The town assembly of the (Czech) Český Těšín even accepted a resolution protesting against this prolonged border closure (Irozhlas, June 15, Reference Kasperek and Olszewski2020).

Analysis of Facebook Pages

The analysis of FB pages of all six Czech-Polish Euroregions underscored the unique position of the Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia Euroregion. It is the only Euroregion that has a single FB page gathering both national parts of the Euroregion – the opposite of the practice of other five Czech-Polish Euroregions, where each national part has a separate page in its own language. Moreover, the Euroregion Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia has the highest number of followers out of all the Euroregions. The COVID-19 crisis and the closed border led to an increase of the followers of this page, which rose from 1,469 (February 2020) to 2,026 (March 2021).

The cross-border integration of the studied divided town might also be evidenced by the existence of bilingual FB pages. We identified 42 FB pages in total, which can be considered as targeting both sides of the town. The FB page of the “Cinema on the Border” festival, organized annually by the NGO Man on the Border in both parts of the divided town, has both the highest number (12,818) and the greatest increase of followers (+1,592) since the beginning of the pandemic – although this could be partially attributed to the migration of festival visitors to cyberspace, given that the 2020 festival could only be held online. Posts on this regularly updated FB page are bilingual.

There are also other FB pages that focus on both parts of the divided town. These are mostly written in Polish only, which is due to the fact that their contributors or authors from the Czech side of the border are members of Polish minority living in Czechia. However, the existence of these FB pages and their focus on both sides of the border (which is not the case in the rest of the CZ-PL borderline) indicates that the divided town is perceived as a joint (living) space.

Findings Based on the Questionnaire

The online questionnaires addressed cross-border flows. Promotion of this survey occurred via the web pages of the Euroregion Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia, both parts of the divided town, local printed and e-media, and social networks, which helped to reveal that there are FB pages in the divided town covering the cross-border territory and target group. The research team recorded 1,519 filled-in questionnaires (59% of respondents were women, and 41% were men), out of which 600 came from the both parts of the divided town itself, and the rest from the close municipalities. We observed a major difference in the response rate from both parts of the border: 81% of all answers came from Polish respondents but only 19% from Czech respondents. Of those respondents, 61% work in Czechia and 39% in Poland. This indicates a rather one-sided orientation of cross-border flow, as will be explained in the next paragraphs. It also reflects that the questionnaire was completed mainly by Polish cross-border commuters working in Czechia. However, the high number of people who took part in the questionnaire also documents an interest of the locals in the topic.

The survey confirmed the findings of the media and the analysis of social networks. It showed that the COVID-19 pandemic introduced uncertainty in the daily lives of inhabitants of the studied divided town. Of all 1,519 respondents, 68% indicated that the pandemic and related border closures had a major impact on their perception of “life securities considered for granted.” For 14%, this impact was average; for 6%, it was minor. Only 10% of all respondents stated they had not observed any impact on their daily lives.

This element of uncertainty had an influence on multiple aspects of daily life. Of all respondents, 64% claimed the restrictions had the biggest impact on their professional lives, whereas 55% experienced them in travel and freedom of movement. The third highest impact, mentioned by 30% of respondents, was the impossibility of having a social life and meeting friends freely. The pandemic also restricted the cross-border use of health care (22%) and of activities in the areas of culture, sports, and education (20%).

Of all respondents, 68% emphasized that the border closures influenced their family lives: 57% claimed that they had to seriously change their plans for the first half of 2020, and 47% stressed that they experienced a temporary forced separation of their family. This was the case of the Polish cross-border commuters working in Czechia, who were forced to make a choice either to earn money in Czechia and to rent accommodation there (to avoid the obligatory two-week quarantine obligation imposed by Polish authorities) or to stay at home with their family without any income or compensation from national sources (which was the case of employees working in their country of permanent residence, who received at least partial compensation when they were unable to work because of the pandemic).

The pandemic also changed the daily organization of family obligations (30%) and worsened family relations (27%) of those surveyed. This heavy impact on the quality of life of borderlanders was chiefly caused by the sudden decision of the Polish government to impose an obligatory 14-day quarantine for everyone entering the country, including cross-border commuters. This led to two principal reactions among Polish cross-border commuters. One group decided to continue working in Czechia, find accommodation there, and be separated from their families. The other group decided to stay home and relinquish either all or part of their income, which also caused significant difficulties for their Czech employers. In many cases of employment in the production sector, these cross-border commuters are men who lack higher education (Kasperek and Olszewski Reference Kasperek and Olszewski2020; Medeiros et al. Reference Medeiros, Ramíréz, Ocskay and Peyrony2021) and who mostly do manual work in professions that require fewer qualifications. Moreover, they are quite often the sole breadwinners in their families. Therefore, the sudden suspension of income brought those families into very challenging situations – which would not have been so severe in the centrally located regions. The image of the borderland as a place offering a good life was damaged.

Despite the efforts of local politicians, the border closures damaged both the perception and the actual process of cross-border commuting. Although border closures did not influence 40% of respondents, almost half experienced a change in their work status or working habits: 15% mentioned that they lost their job because of the pandemic-related border closures. Even though 29% of respondents were able to keep their jobs, their working conditions worsened, and 6% started to work online. Moreover, 60% of respondents feared the possibility of job loss seriously and 10% moderately, whereas only 22% of all respondents declared the opposite.

Although cross-border commuting is an important element of cross-border integration of the studied territory, it is not the only one. According to 37.5% of all respondents, border closures forced them to seek an alternative to their planned health-care treatment. Of these respondents who were influenced by the border closure in the health-care sector, 58% mentioned the necessity to look for an alternative to the already planned treatment in the neighboring country. Of those respondents, 52% complained that the border closures increased the actual level of their health-care costs. In addition, 25% of the respondents mentioned that border closures had complicated their (or their children´s) school attendance. This can be attributed to the fact that children from the Polish part of the town attend schools for the Polish minority members on the Czech side of the border, where Polish is the primary language of instruction.

Conclusions

The findings of this article showed that the studied divided town has achieved a high level of cross-border integration: there are considerable levels of cross-border flows, an existing network of cross-border cooperation institutions coordinated by the Euroregion Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia, and a strong sense of togetherness. The latter is reflected in the active cross-border civic society, and it is also visible in cyberspace, as evidenced by numerous FB groups targeting audiences from both parts of the divided town. Following Kaisto’s (Reference Kaisto2017) interpretation of Lefebvre´s spatial triad, there are many inhabitants of the studied space who identify with the twin-city concept. Their spatial perceptions, cross-border flows, and lived experiences involve both sides of the river and reflect a developed communality (Joenniemi and Sergunin Reference Joenniemi and Sergunin2011, 120). They also understand the open border as a norm and perceive both sides of the river as a joint living space. There is also a functional network of institutions cooperating across the border, coordinated by the Euregion Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia.

This might seem to contradict Durand and Decoville (Reference Durand and Decoville2019, 174), who foresee “…the low mutual social trust between populations living on either side of the border and only few cross-border activities in the new EU.” However, the divided town can instead be considered a rule-confirming exception, given that both sides share a common history, the language barrier is minimal, the Polish minority in Czechia acts as a cooperation bridge, and there are numerous job vacancies available for Poles on the Czech side of the border.

However, the border closures damaged the image of this divided town as a good place to live because they introduced an element of uncertainty, which was experienced mainly by Polish cross-border commuters working in Czechia and using public services there. The questionnaires showed that cross-border commuters started feeling uncertain about their job security: at the beginning of 2020, cross-border commuting was considered to be a “normal” option, whereas only a year later, it was deemed a potential risk.

On the other hand, even though the reinstatement of the border barriers and checks worsened the quality of life in the divided town, it has not contributed to the rise of animosities between the residents of one part of the town and their neighbors living in the other. All protests observed during the studied period were against the national capitals as symbols of the low sensitivity of central governments vis-à-vis border regions. Moreover, these protests – often claiming that restrictions of border crossing were against European values – were sometimes directed against both national capitals at the same time and might even have contributed to the increased feeling of (local) togetherness.

Therefore, we can conclude that there is a high probability of the return to borderless normality in the divided town once the pandemic is under control. The existing functional and ideational dimensions of cross-border integration are reflected in a strong network of local actors, supported by the Euroregion as a key cross-border institution. To avoid dramatic worsening of life in the divided town, the Euroregion proposed a special scenario of cooperation in emergency situations, which would be applied in the case of repeated border closures. This could eliminate uncertainty, which has been causing problems as serious as the restricted borders themselves (Böhm Reference Böhm2021, 144).

Acknowledgements

The author wants to thank the Euroregion Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia and Dr. Jacek Siatkowski. He also wants to thank both anonymous reviewers, who helped to improve this article.

Disclosures

None.

Financial support

This article was written with financial support from the NCN of Poland, Programme Opus19, project no 2020/37/B/HS5/02445.