Preamble

Tejumola (Teju) Olaniyan is the source of inspiration for this article. He reached out to me at the conceptual stage of the conference on “Pleasure and the Pleasurable in Africa and the African Diaspora” that he organized at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in April 2017. His email of February 6, 2016 reads in part: “I am in the early stages of planning [the conference]…Please think with me, and help with possible names I can interest, including, if possible, specific areas of coverage of the topic a name might fit into. I am hoping you too will consider imagining something on the topic from the vantage point of your discipline.” I had not written anything explicitly on “pleasure” before Teju’s invitation. So, I was reluctant at first to offer any advice or even to participate in the conference. But he persisted, and I relented. This article is the result of his vision and encouragement.

Introduction

The Palm-Wine Drinkard (1952) by Amos Tutuola is the first novel in English by an African, published outside Africa. Authored by a Yorùbá with sixth-grade formal schooling, it is also the first novel by an African to attract the serious attention of the North Atlantic literary circle. Critics have widely commented on the author’s literary style and the book’s phantasmagoric panache and place in the African folkloric genre. Many of them, however, have overlooked the subject of the book: palm-wine and a man’s insatiable love of it. The main character’s name in the novel, Drinkard, derives from what he does best—drinking palm-wine. The child of the richest man in his town, Drinkard started imbibing palm-wine at the age of ten. He was the oldest of eight children, and all but Drinkard were hardworking. In contrast, Drinkard did not know how to do any work; all he wanted was to drink “from morning till night and from night till morning” (Tutuola Reference Tutuola1953:7). Surprisingly, Drinkard’s rich father rewarded him for his spirituous dedication. He gave him a nine-mile square plantation of 560,000 palm trees and hired a wine tapper to serve him alone. Drinkard tells us that at the peak of his drinking career (when he was about 25 years old), he consumed 225 kegs of palm wine every day (5625 liters, assuming 25-liter kegs). With a life committed to the enjoyment of palm-wine, it is not surprising that Drinkard had an “uncountable” number of friends who drank with him from morning until late at night. He was only 25 years old when his tapper suddenly died after falling off one of Drinkard’s palm trees. The main focus of the book is the quest of this palm-wine-loving young man to bring back his tapper from the land of the dead.

The weeks and months following the tapper’s death were challenging for Drinkard. He looked in vain for a new tapper, but none could tap palm-wine to his satisfaction (Tutuola Reference Tutuola1953:9). His social life began to unravel. With the supply of palm-wine gone, Drinkard’s friends also stopped visiting him. As a Yorùbá proverb puts it, ẹsẹ̀ gìrìgìrì nílé à ńjọ̀fẹ́, á ńjọ̀fẹ́ kú a kò rí ẹnìkankan mọ́: “the multitude of visitors is ever-present in the house of a generous person, but they will disappear when the generous person or the act of generosity is no more.” Once the supply of palm-wine dried up, Drinkard lost his drinking friends. When he saw one of them in the town and greeted him, the “friend” politely responded, “but he did not approach me (Drinkard) at all, he hastily went away” (Tutuola Reference Tutuola1953:9). The morality of the story is obvious: his drinking companions were only involved in a transactional relationship with him, based on the endless supply of palm-wine, and they had no use for him once it dried up. Depressed but hopeful, dogged and yet unremorseful, Drinkard embarked on a journey to bring his tapper back from the land of the dead. Finding his tapper was the only way for him to regain his hedonistic ways and the conviviality of his drinking companions.

The object of the plot of Amos Tutuola’s first and most successful novel —palm-wine—is useful for thinking about the Yorùbá ideas of pleasure. What pleasure stands for in contemporary English language is close to what the Yorùbá call ìgbádùn, transliterally “lived sweetness.” Ìgbádùn can also be interpreted as enjoyment. There are many other stories in the vast Yorùbá literary corpus (oral and written) in which palm-wine is at the center of pleasure or ìgbádùn but not in the indulgent way as portrayed in The Palm-wine Drinkard, where the ultimate desire and objective of living was to drink palm-wine. As many critics (e.g., Ogundipe-Leslie Reference Ogundipe-Leslie1970; Owomoyela Reference Owomoyela1999) have noted, The Palm-Wine Drinkard draws heavily on the plot and spirit of Yorùbá folklores, but the entire narrative is ultimately the invention of the author. This invention is about the decomposition and recomposition of language to generate wonders and fantasies about pleasure. Hence, some recent critics have described the novel as a “pioneering work of African science fiction” (Moonsamy Reference Moonsamy2020). For Drinkard, the ultimate purpose of living is the pleasure of drinking palm-wine, and the quest to achieve this purpose trumps all other desires, aspirations, and feelings. The mainstream Yorùbá thought neither holds this hedonistic desire nor even conceptualizes the world in absolute or extreme terms. Therefore, in Yorùbá ontology, there is not a single ultimate pleasure in and of itself, and pleasure is not contrasted with pain.

Nevertheless, the scintillating narrative of the pleasure and ordeal of the protagonist in The Palm-Wine Drinkard is useful for interrogating the Yorùbá theory of pleasure. The centrality of palm-wine in that phantasmagoric novel originated from the situatedness of this powerful drink at the intersection of different signs of Yorùbá culture and its sociology. Hence, just as Tutuola used it to ground his imaginative rendering of an alternative world to the one he lived in, I also find it a useful entry point for contemplating the Yorùbá ontology of pleasure. My task here is two-fold. In the first part, I examine the Yorùbá ontology of pleasure through the analysis of one Yorùbá myth-historical source in which palm-wine is implicated. In the second part, I use archaeological evidence to explore the objective reality of pleasure in the long-term history of the Yorùbá. In both approaches, I focus on the ontology and materiality of pleasure to achieve two goals: first, to understand how the ancestral Yorùbá conceptualized and lived the experience of pleasure, and second, how they used the ideas and practices of pleasure at the levels of ordinary experience and high culture to construct social order, delineate social difference and power relations, build community, and navigate the process of being and becoming in the past millennium.

Yorùbá Myth of Origin and Ontology of Pleasure

It is not an accident that palm-wine is at the center of the first internationally famous novel written in the English language by a Yorùbá author. Palm-wine has been the object and subject of many Yorùbá performative genres of pleasure that simultaneously speak to critical reflections about value, meaning, and social order, as well as entertainment. There is hardly a safer “subject” or “commentary” that explores the serious and the playful than a palm-wine story. In this sense, it may not be surprising that the experience of pleasure, and the role of palm-wine in it, is also at the center of the Yorùbá origin myth or creation story. This is my retelling of it.

Once upon a time, the supreme deity and sky-god, Olódùmarè, decided to create the earth. At that time, there was only the sky and the water below it. There was no land or rock, mountains, or vegetation. Olódùmarè wanted his deity-deputies (Òrìṣà) to descend from the sky, create land (the earth), and populate it with plants, animals, and people. In order to make this happen, the sky-god turned to Ọbàtálá, the most senior and trusted among these deity-deputies. Olódùmarè gave him the àṣẹ (the power-authority “to make things happen and change,” Drewal et al. Reference Drewal, Pemberton and Abiodun1989:16) to lead a group of divinities to perform this important task.

The project started well, and Ọbàtálá was effectively discharging his duties as a leader. He motivated all the divinities to perform their assigned roles. He led them to a place they called Ilé-Ifẹ̀, and he used all the tools of àṣẹ that Olódùmarè had given him to create land, plants, and animals. He was also a sculptor, so he modeled anthropomorphic figures with clay from the soils he created. He took these figures to Olódùmarè, who breathed into them and transformed them into human beings. Everything was going well as planned until Ọbàtálá began to indulge in drinking the wine tapped from the palm trees that had just been created. He was not the only deputy-deity enjoying the alcoholic beverage. Others joined in the tasty but intoxicating drink. It was, however, only Ọbàtálá who drank himself into a stupor and became unable to fulfill the role of leadership he was charged to perform. Under the influence of alcohol, he sculpted deformed figures who were turned into people with physical challenges. Another member of the team and a rival, Odùduwà, took advantage of the situation by taking over the paraphernalia of authority that gave Ọbàtálá the àṣẹ to lead. By the time Ọbàtálá became sober and regained consciousness, it was too late. Odùduwà had completed the task that Ọbàtálá had started.

Under the leadership of Odùduwà, a new world had been created; the swamps had been drained, gullies filled, and Ilé-Ifẹ̀ was transformed into a thriving city with Odùduwà as its recognized king. In that “moment” of unconsciousness, Ọbàtálá had lost all his political powers to Odùduwà. The former regretted his palm-wine over-indulgence, but he was not bitter. He atoned for his transgressions by vowing never to drink palm-wine again. This vow did not enable him to regain his lost political power, but he regained his spiritual and moral authority among the other Òrìṣà. Since then and to the present day, Ọbàtálá’s descendants and devotees (priests and priestesses) have abstained from drinking palm-wine. As part of this atonement, all the materialities of pleasure that give power its raison d’etre are rejected by the Ọbàtálá ritual field. His devotees do not wear the red and blue glass beads that became the paraphernalia of power and authority under Odùduwà, although these have since become objects of universal desire and pleasure among the Yorùbá (I will return to this later). And, as part of Ọbàtálá’s periodic cleansing rituals, his diet eschews palm oil and salt, basic ingredients of taste in Yorùbá culinary culture. With this atonement, Ọbàtálá became the spiritual leader of the world and the father-figure for all the other deities (Òrìṣà), according to the Yorùbá belief. He regained his credibility at the cost of eschewing the pleasures that the other deities were ordinarily able to enjoy. The consequence of all of this was that the political and spiritual power that originally concentrated in the hands of Ọbàtálá alone was divided in half, with spiritual power going to Ọbàtálá and political power to Odùduwà. However, the latter realized that he needed Ọbàtálá as an ally to govern the new city effectively, and this laid the foundation for the complementarity between these two as the basis for creating social order.

The above story is at the core of Yorùbá cosmology. It is a moral code and a point of reference for the danger of unbridled pleasure. Ọbàtálá’s over-indulgence in palm-wine and his abdication of sacred duty almost aborted Olódùmarè’s plan to create the world. He paid dearly for it by losing his political leadership. Therefore, his lapse in judgment over a pleasurable drink is a cautionary tale in the Yorùbá ontology of power, leadership, and morality. The story defines human relationships with the environment (palm-wine), with one another (leaders and followers), and with Olódùmarè (the supreme being). It is a reference point for measuring and interrogating appropriate behavior in one’s self and others. That momentary lapse in judgment based on pleasure and over-indulgence in palm-wine also allowed a series of redemptive actions that are canonized in Yorùbá cosmology. From Ọbàtálá’s drunkenness to his redemptive act, we can begin to understand the Yorùbá theory of pleasure and how the ontology of pleasure is implicated in the construction of personhood, nature, society, statehood, and power, and in the very ideas of excess, moderation, and self-denial.

Of all the Yorùbá deities, it is only in Ọbàtálá’s practical experience and spiritual essence that the social critique of unbridled pleasure, defined by excess and greed, is most elaborated as the foundation of anarchy and ruin for society and the individual (Eleburuibon Reference Eleburuibon1988:67–69). In Ọ̀bàrà, one of the sixteen books of Ifá (the Yorùbá divination corpus), Ọbàtálá is described as an ascetic deity who rejects the everyday materialities of pleasure that define the norms of tastefulness, self-realization, and social mobility.

Ọbàtálá defies the social norms of pleasure. He has access to all the materialities of normative pleasure; however, he chooses the alternatives that others may characterize as displeasure or untasteful such as eating plain food (without palm oil and salt) and wearing only white clothing. Ọbàtálá’s experience poses a challenge to the exterior theory of pleasure, that “what makes a feeling pleasurable is something external to the experience” (Smuts Reference Smuts2011:242). The experience of Ọbàtálá is internal to the satisfaction derived from his rejection of ordinary and normalized everyday practices. That rejection (and its substitute) is what defines who Ọbàtálá has become and will always be. It can be argued that this satisfaction is a form of pleasure because it is a choice. Ọbàtálá had the abundance of what defines pleasurable taste and aesthetics, but he shunned those pleasurable things and instead chose an ascetic lifestyle. Ọbàtálá’s post-drunken state marked a moment of self-consciousness, redemption, and alertness from which he derived the pleasure that rehabilitated him in the Yorùbá cosmological realm. However, Ọbàtálá did not condemn those things he rejected, but he became a critic of their excessive use. In the literary corpus of the deity, the everyday pleasure and the pleasure that came with political power, conquest, and economic prosperity were necessary and desirable. However, the Ọbàtálá School warns of moderation, compassion, and justice for the marginalized. This grand old deity of the Yorùbá pantheon does not stop there. He also extolls a different kind of pleasure associated with piety, frugality, simplicity, cleanliness, and good health. In addition, his cultural biography emphasizes that self-denial is the virtue and pleasure of self-realization (Ogunsina Reference Ogunsina2013; Eleburuibon Reference Eleburuibon1988).

The pleasure in Ọbàtálá’s experience is about desire, moderation, and responsibility. It also raises moral and spiritual questions about service to others. The framing of pleasure in the Ọbàtálá School of Thought is a sharp contrast to the atomistic self-interest of Tutuola’s Drinkard, for whom pleasure exists for its own sake, extreme, addictive, and non-consequential. Therefore, in Drinkard’s world, there is no possibility of reflection or redemption. Yet, both palm-wine stories call attention to the sociality and shared experience of pleasure. That is, the individual cannot pursue and achieve pleasure on his or her own, but only within the community. This could be the organic community of the family, the community of the deputy-deities led by Ọbàtálá, or the transactional community of the Drinkard’s friends. Hence, the Yorùbá saying: ẹnìkan kì í jẹ kí’lẹ̀ ó fẹ̀ (“A one-person feast cannot fill the house, or attract and create the multitudes and abundance of people, things, and ideas”). And another Yorùbá adage says, ẹni t’ó d’áyé jẹ á dá’yà jẹ (“a person who enjoys pleasurable life alone will also suffer misfortune alone”). These aphorisms sum up the ontology of the Yorùbá, that pleasure is the basis of sociability. Pleasure cannot be realized through the personal corporeal but via the social network of people, and it must serve the purpose of reinforcing and expanding the community. A person is enlarged socially by creating pleasurable moments that bring many people together. Hence, what the Yorùbá call ìgbádùn (pleasure) emphasizes performative, public, and shared experience for it to be moral, ethical, purposeful, and justified, and to serve the ultimate purpose of community-building.

Abundance and Pleasure in History

To illustrate specific aspects of the above generalizations, I will turn to an ancient Yorùbá city whose name means “house of abundance,” “house of cosmopolitanism,” or “house of diversity” (Ogundiran Reference Ogundiran2020:108; also see Abiodun 2015:221–22). This is the very same Ilé-Ifẹ̀ where the creation of the world began, according to Yorùbá cosmology. It was there that the deities created the first land and people. Hence, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ is the cosmological city of the Yorùbá; the first home of the òrìṣà (deities) on earth; the place where Ọbàtálá created the first people; and where Ọbàtálá’s transgression and redemption took place. And, according to Yorùbá myth-history, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ is also the place where the first divine kingship was established and whence the other dynasties that later populated the Yorùbá region originated. Archaeological and other lines of historical evidence indicate that Ilé-Ifẹ̀ produced and dispensed the paraphernalia of divine kingship authority—iyùn and ṣẹ̀gi—to those other dynasties (Horton Reference Horton and Akinjogbin1992; Ogundiran Reference Ogundiran2020).

The novelty of the art and the unique array of the material culture of classic Ilé-Ifẹ̀, from approximately AD 1000 to 1420, is second to none in the repertoire of Africa’s cultural history, south of the Sahara (Blier Reference Blier2015; Drewal & Schildkrout Reference Drewal and Schildkrout2009; Willett Reference Willett1967). The archaeological records of the past century attest to the broad range of pleasurable living that sustained the ancient city. If pleasure originated from want and deprivation in Western ontology (e.g., Sahlins Reference Sahlins1996:398), it originated from abundance in Yorùbá thought. The origins of the “House of Abundance” go back to the seventh or eighth century, but it was in the eleventh century that it developed into a significant urban center (Ogundiran Reference Ogundiran2020). The archaeology of Ilé-Ifẹ̀ has revealed that the city lived up to the meaning of its name. It was an emporium and the most important commercial center in West Africa south of the River Niger between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries. The city was also a cynosure of diversified crafts production ranging from iron, glass, and textiles to terracotta, stone, and copper-alloy sculptures. Most important, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ produced epistemic objects through which the pleasure of self-realization was materialized, and its residents were engaged in elaborate performative pleasures of memory-making, community formation, and identity-making.

Epistemic Objects as Objects of Pleasure

Recent archaeological investigations and geochemical studies have now convincingly confirmed that Ilé-Ifẹ̀ developed a unique technology for glass manufacturing sometime around the eleventh century, if not earlier (Babalola Reference Babalola2017; Lankton et al. Reference Lankton, Ige and Rehren2006; Ogundiran & Ige Reference Ogundiran and Ige2015). In the ancient city’s major industrial park, Igbó Olókun, indigenous scientists and artisans experimented with and perfected the primary manufacture of glass using the recipe of granitic materials (especially pegmatite) and snail shells. The result is the chemical signature of High Lime, High Alumina (HLHA) which Ogundiran & Ige (Reference Ogundiran and Ige2015) have named “Yorùbá glass” (for the uniqueness of this glass chemistry in the ancient world, see Rehren & Freestone Reference Rehren and Freestone2015). The Ifẹ̀ glassworkers used the pegmatite/snail shell recipe to produce two major types of glass beads, ṣẹ̀gi (blue beads, based on the addition of cobalt to the recipe) and iyùn (red beads, derived from adding copper and tin to the mixture). They also made other color types, ranging from different hues of yellow and green to brown and black. Their mastery of glass production using locally abundant materials demonstrates a sound understanding of the mineralogical properties of their environment’s geology. Irrespective of color, these beads are dichroic. They show one of two different colors in different light exposures ranging, for example, from blue-green to blue-yellow for ṣẹ̀gi (blue beads). This dichroic quality is a product of the large composition of mica (in addition to quartz and feldspar) in the granites that served as the bulk raw material for glass production. This dichroism is believed to “emit” the energy of beauty, transcendence, and magical qualities and was a constant source of wonderment, admiration, and desire among the Yorùbá and their neighbors (Euba Reference Euba1981; Fage Reference Fage1962; Ige Reference Ige and Roemich2010).

These Yorùbá glass beads, especially iyùn and ṣẹ̀gi, were objects of power, wealth, and social potency in classic Ifẹ̀ as well as in the surrounding Yorùbá region and many parts of West Africa. For the Yorùbá, in particular, these beads were the means of legitimizing divine kingship and ritual authority. Likewise, they were the ultimate objects of aspiration for self-realization, since they served as a means of storing value across generations (for elaboration on Yorùbá self-realization, see Barber Reference Barber and Guyer1995). The pursuit of pleasure, in any society, cannot be divorced from the desire for self-realization, a sociological and psychological condition that usually has a strong material signature. Hence, the objects that fulfill the quest for self-realization also tend to be objects of ultimate desire and pleasure. For this reason, the glass beads manufactured in Classic Ilé-Ifẹ̀ were the ultimate objects of desire in the Yorùbá world and beyond. They were situated in multiple locales of practice—political, social, economic, cultural, philosophical, religious, and spiritual—where they signified meaning and value. In this regard, glass beads were epistemic objects for the ancestral Yorùbá. They disclosed the meaning of the practices and ideas in which they were embedded and made the meaning of other objects possible. For example, it is through the glass beads that we begin to understand the meanings and meaningfulness of the Yorùbá divine kingship, and it is through these beads that the identities of the various òrìṣà in the Yorùbá pantheon are manifested (Drewal & Mason Reference Drewal and Mason1997).

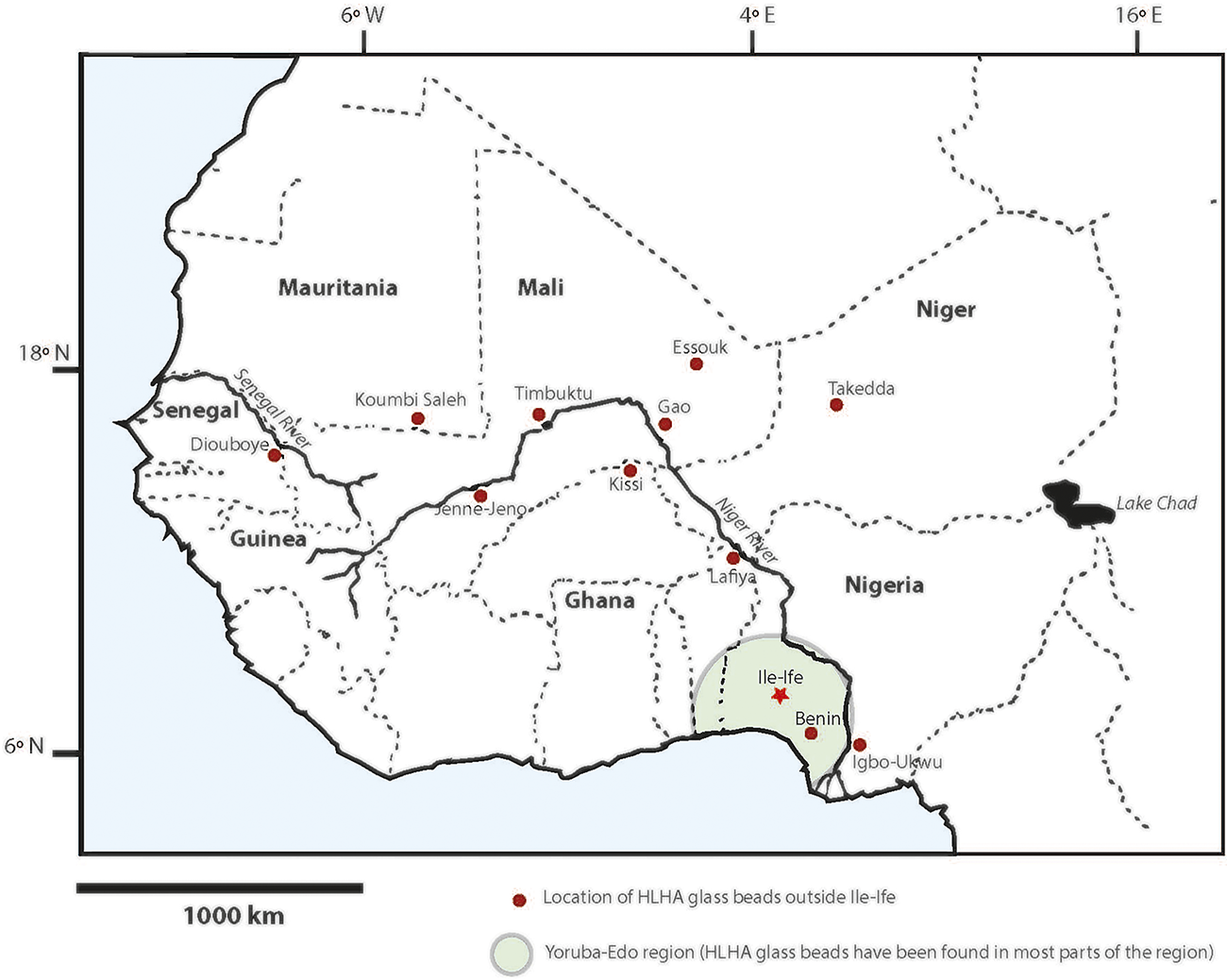

The universal qualities of glass beads as objects of desire, value, power, and self-realization also give them their meaning as objects of pleasure. They can be converted into many categories of pleasure and be used to grant or withhold pleasure to others. Between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries, the glass beads produced in Ilé-Ifẹ̀ were used to mediate social relationships in the Yorùbá world, especially between the powerful and their subordinates, and in inter-state relations (Ogundiran Reference Ogundiran2020:93–149). As epistemic objects and objects of everyday desire, they were the primary means for asserting legitimacy (political power) and promoting and demoting people on the social ladder. The elaborate use of beads in sartorial culture is indicative of this desire and the pleasure derived from it (see Fig. 1). Of course, the men and women of power and wealth were the individuals who had the most glass beads and who could use them most effectively to project their status, sartorial splendor, and self-realization. The human figures in the classic art of Ilé-Ifẹ̀, Ọ̀wọ̀, and Èsìẹ́ show that beads were central to sartorial pleasure in the ninth through the early fifteenth centuries, with related traditions continuing in the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. As beads were held to be objects that brought joy and pleasure, signified power, prestige, wealth, and authority, radiated wellness, and projected self-realization, the wearer was by association a subject of desire and emulation ( àwòkọ́ṣe ) and an object/subject of aspiration.

Figure 1. Representation of beads in the attire of a Classic Ifẹ̀ brass figure

As the site for primary glass manufacture, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ became the emporium of the Yorùbá world and the legitimizing city for the Yorùbá divine kingship. The city stood for the utopian experience of abundance, wellness, and pleasure for many potentates and people living across and beyond the Yorùbá-speaking world. During the Yorùbá classic period, it was in Ilé-Ifẹ̀ where beads were most elaborately worn as adornments, encircling all the joints and different parts of the body, from the head to the ankle (see Fig. 1). Ọsìnfẹ́kundé (b. ca. 1795), an enslaved Yorùbá in Brazil, gave us an idea of the sartorial importance of beads during the later period (early nineteenth century). He noted that the size, quality, and quantity worn “are a sign of rank and wealth … The important people wear up to four strings of … beads, hanging down to the navel, and the king wear[s] a great number” (Lloyd Reference Lloyd and Curtin1967:265). Men of means sewed beads onto their clothing, and women adorned their woven and plaited hair with stringed beads. These beads, as an integral part of clothing, “enhance the image of their wearer, affirming an authoritative and substantial presence that hints at the divinity believed to reside in every Yorùbá person” (Abiodun Reference Abiodun2014:168). The Europeans traveling through the Yorùbá region during the 1820s variously commented that the kings and nobles found “large handsome coral beads” the most agreeable gift. One such gift of beads from British explorer Hugh Clapperton in 1826 threw the king of Ọ̀yọ́, Aláàfin Ọmọ́ṣọlá Májǒtú, “into a transport of joy” (Lander Reference Lander1830:113).

The classic Ifẹ̀ glass beads were among the social goods that circulated and exchanged hands locally and across the region in the eleventh century, but their dichroic luminosity and use as a symbol of power and authority soon set them apart from other social goods. They were held as magical and spiritual objects. Mass production of ṣẹ̀gi pushed these blue glass beads into the sphere of mass consumption. As a material representation of self-realization, joy, and pleasure, they were possibly used by the thirteenth century as a unit of measuring value and a means of payment for other goods, services, and debts. In this regard, they fulfilled the functions of money, and as a result, glass beads were not only reified but also fetishized (Ogundiran Reference Ogundiran2002). To meet the considerable demands for this object of multivalent pleasure, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ increased its bead production. It has been estimated that over four hundred years (ca. AD 1000–1400), billions of glass beads were produced in Igbó-Olókun, the largest industrial park in the city (Ogundiran Reference Ogundiran2020:102).

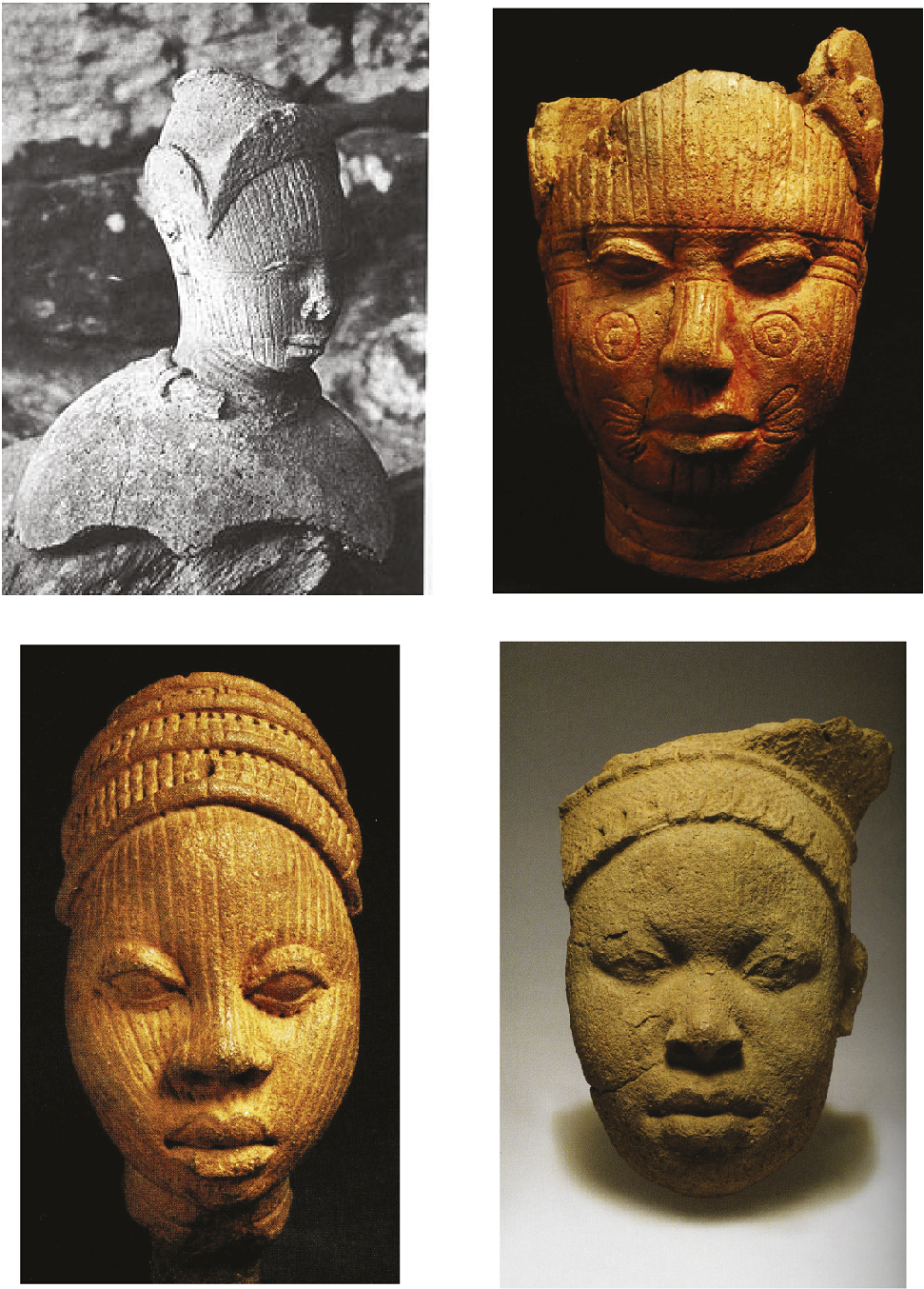

The desirability of the Yorùbá glass beads for the pleasure and well-being of the body, mind, and soul spread across the West African region. We now know that Ilé-Ifẹ̀ traded its glass beads as far as Koumbi Saleh in Ghana Empire; Gao, Timbuktu, Essouk-Tadmekka in Mali Empire; Igbo-Ukwu in present-day southeast Nigeria; and other places in between (see Fig. 2). The dichroic qualities of these beads made them objects of desire and pleasure across West Africa down to the early modern period, when the Portuguese and the Dutch made a lucrative profit trading the Ifẹ̀ blue glass beads from one port to another along the western and central African coastlines as far as the Kongo Kingdom in the east and Gold Coast in the west (Fage Reference Fage1962). As the sole maker and distributor of these highly desired epistemic objects, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ was able to define and institutionalize the rituals of pleasurable “practices, norms, values, morals, and beliefs” that these bead products represent (Styhre Reference Styhre2002:231). These objects were also the basis for the rationalization of power, war, political expansion, imperial thinking, labor organization, and the hierarchization of the political landscape during the Classic Yoruba period. The physical (embodied) was united with the psychic in this rationalization and signification of glass beads. The names of the two dominant bead forms produced in Ilé-Ifẹ̀ came to define desire and pleasure in gendered terms. Even today, both ṣẹ̀gi and iyùn are used as gender-female names, thereby feminizing the ultimate object of desire and pleasure in Yorùbá thought and practice.

Figure 2. Distribution of HLHA (Yorùbá) glass in West Africa, ca. 1100–1420 AD

The Pleasure in the Art of Commemoration

One of the hallmarks of Classic Ilé-Ifẹ̀ was its prolific plastic art traditions, especially the naturalistic sculptures devoted to commemorating the ancestors. These terracotta and copper-alloy (mostly brass) figures of the ancestors were produced in various workshops that could be found in the city between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries. At the peak of the city’s prosperity in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, many families commissioned near life-size sculptures of their departed elders. The sculptures were used in the commemorative ceremonies and solemn religious activities that connected the past and present and provided directions for the future. Hundreds of these sculptures have been found all over the ancient city. A few others, in the same style and artistic traditions, have also been excavated in other parts of the Yorùbá region, including Ọ̀wọ̀, Òṣogbo, and Ìkìrun. They were sculpted with fidelity to the personality and individual characteristics of the deceased ancestors being immortalized, including the clothing style and facial markings that defined the identity of their lineages and historical backgrounds (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Classic Ifẹ̀ naturalistic figures

These commemorative heads were placed on the lineage altars and were the focus of veneration by the descendants. However, the display of these ancestral heads was not all private. They were part of the annual public displays in ceremonies and parades, during which the descendant communities reaffirmed their rooted identity and renewed their loyalty to the ancestral lineage and to one another. These festive occasions were periods of pleasure-making that included pomp and pageantry as well as feasting. The current égúngún festivals—the annual commemoration of the ancestors, so ubiquitous in almost all contemporary Yorùbá villages, towns, and cities—are indicative of the kind of spectacle that would have characterized the ceremonies in which these sculptures were embedded in Classic Ilé-Ifẹ̀ (Willis Reference Willis2018). The passing of an elder, survived by children and relatives, was a moment of celebration. The survivors were required to give the deceased elders a befitting burial and set up an altar in their honor and for their commemoration. The burial ceremonies and the annual commemorative festivities were rituals of regeneration which involved feasting and reveling. They were moments of pleasure that required huge investments of resources—labor and material—in planning and execution. Therefore, these festive occasions were often the drivers of local and regional economies in many parts of the ancient world (McAnany & Wells Reference McAnany and Wells2008). At the height of Ilé-Ifẹ̀’s prominence, in the mid-fourteenth century, hundreds of such ancestral figures were paraded annually in the streets and alleys of the city, most of which were ornately paved with potsherd tiles in red and black colors (see Fig. 4). The descendants would have accompanied each figure, with drummers leading the songs of praises to the ancestor it represents.

Figure 4. A potsherd pavement in Ilé-Ifẹ̀

Pleasure in the Private Space

Aside from the pleasure embedded in sartorial performances and public festivals, the interiority of the domestic space offers an intimate insight into everyday pleasure and pleasurable living at different periods of Yorùbá history. The excavations of residential units in Ẹdẹ-Ilé, a colony of the Ọ̀yọ́ Empire during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, have yielded rich material records of the embeddedness of pleasure in the everyday lives of the inhabitants. These materialities provide a wealth of information for thinking about pleasure during the era of the merchant capital revolution in West Africa, a period when the region was entangled in the global circulation of goods and enslaved people via the Atlantic trading voyages. In the domestic spaces of Ẹdẹ-Ilé, pleasure was highly gendered, and the experience of pleasure has imprints of class differentiation. Of the various domestic contexts that were excavated in Ẹdẹ-Ilé, the archaeologically richest site is the governor’s residence (Ogundiran Reference Ogundiran2009). Here, we came across a wide range of feminine grooming artifacts in the cooking area of the residence. These artifacts include combs, a hairpin, and pendants made of bone and wood (see Fig. 5). We also encountered spindle whorls (for spinning cotton into thread), tobacco pipes, a gaming disk, a fragment of an imported gin bottle, and imported seed beads, among other items. Based on the logic of the Yorùbá division of labor, this must have been a place in which women congregated, cooking meals for the household, spinning cotton, and performing other chores. However, they also spent some time in between these activities for the pleasure of personal grooming and gaming.

Figure 5. Artifacts from Governor’s Quarter, Ẹdẹ-Ilé, seventeenth and eithteenth centuries

In addition, of all the nine excavation loci in the town, the governor’s residence has produced the only evidence of horsemeat consumption. Of more than 113 bones and teeth of horses identified, all but one were found in the governor’s residence. Horses were the backbone of the Ọ̀yọ́ Empire’s military strength, and they were also the most expensive properties. Only the political elite owned them for prestige and military purposes. As a frontier colony and outpost of the Ọ̀yọ́ Empire, Ẹdẹ-Ilé enjoyed the privilege of receiving supplies of horses from the capital to maintain the military might of the empire in the borderland. A large number of the horse remains in the governor’s quarters show that whenever these horses were no longer able to support the defensive and military needs of the colony (due to old age and infirmity), they were deployed to satisfy the gastronomic needs of the governor’s household.

It should be noted that the sumptuary law of Ọ̀yọ́ only permitted the political elite and their households to eat horsemeat. As Richard Lander observed during his visit to the capital (Ọ̀yọ́-Ilé) in 1827, horsemeat is agreeable to the “refined palate of the higher ranks; the lower orders being forbidden to eat of it…” (Lander Reference Lander1830:203). The law also forbade the selling of horsemeat in the market. Therefore, horsemeat was a delicacy and its consumption a mark of rank, class, or affiliation with power. Considering the high price of horses, only the old or infirm horses were used for food. The spatial restriction of horse bones to the governor’s quarters in Ẹdẹ-Ilé demonstrates a strict adherence to the sumptuary law, showing that only those in the governor’s compound enjoyed the slightly sweet, tender meat of horses. This location also produced the only evidence, in the form of case bottle fragments, for consumption of aguardiente and rum, imported from Brazil and Europe, respectively. Likewise, the combs, hairpin, and pendants made of bone, wood, and possibly ivory and found in the governor’s compound were not present in other excavation loci at Ẹdẹ-Ilé. The concentration of artifacts that reference different activities, work and personal grooming, gaming, and consumption of assorted and restricted foods and drinks marked out this site as a multivalent space of gendered and class-specific pleasure.

Conclusion: On the Senses and Meaningfulness of Pleasure

I opened this essay with a discussion of a novel by a Yorùbá writer to explore the implication of pleasure in the way a fictional character constructed his identity in relation to the world. I contrasted this with the Yorùbá myth-historical story of origin in which pleasure is also implicated in the construction of a people’s consciousness of who they are, where they came from, how they arrived in (or made) the world, and the quest to establish social order and meaningful life on earth. The Yorùbá identity and sense of self as a community of practice cannot be understood without their myths. The myth of creation and the relationship between Ọbàtálá and palm-wine enable us to reflect on the meaning and meaningfulness of pleasure in deep-time Yorùbá thought and practice. The myth provides insights for framing the ontology of pleasure, which, in turn, helps us to better understand the lived experience and objective realities of pleasure as a social and sensory practice.

Pleasure is a hyper-material experience that permeates the different domains of senses—gastronomical (food and drink), aural (instruments and music), sartorial, visual, and olfactory. With archaeology as our window into the past, one cannot avoid unrolling the scroll of material indicators of pleasure. However, my interest here is not to establish an inventory of pleasurable things in the Yorùbá past. Rather, I have focused on exploring how pleasure is implicated in deep-time Yorùbá history, what it meant, how it was meaningful, and what the Yorùbá practices of pleasure reveal about the other domains of culture and social lives. Pleasure was more than a background to the history of those cultural domains and social lives. It was a major driver. It is true for the Yorùbá and other societies that pleasure has shaped the contours of war and peace, as well as cooperation and hostility, and served as the impetus for discoveries and innovations, interactions and exchanges, including trading relations over short and long distances (as exemplified by the pleasure of glass beads).

I have explored a few of the senses of pleasurable experience in Yorùbá history, emphasizing the shared experience of pleasure through sartorial expression, festivals and arts of ancestor veneration, and domestic interiority mediated by class and gender. One of the highlights of this article is that pleasure as a subject of inquiry is more than the sum of the experiences, senses, and materialities which constitute it. Pleasure transcends the moments or feelings of desire, comfort, leisure, relief, and taste. The pleasure of feasting, for example, neither begins with nor ends with feasting. It is located in the matrices of worldview, power, sociality, self-realization, identity formation, community building, rituality, political economy, and the nexus of production-distribution-consumption, to mention but a few.

Also, as a materiality of worldview, the pleasure of wearing beads of dichroic glass in Classic Ilé-Ifẹ̀ was more than a fashion statement. The sartoriality of glass beads activates the pleasure embedded in the worldview of political and social order and the place of the individual and community in that order. Ilé-Ifẹ̀ packaged its technological know-how (glass bead production) as knowledge capital. It used this capital (cultural materiality) to build the first empire in the Yorùbá world, frame a new theory of knowledge about the world, create a new system of values and beliefs about sociality and self, and refashion a new vision of social order for a vast region (Ogundiran Reference Ogundiran2020; see also Wells & Davis-Salazar Reference Wells, Davis-Salazar, Wells and Davis-Salazar2007:4 for a related context in ancient Mesoamerica). The city of abundance used this knowledge capital to satisfy the desire for glass beads as objects of pleasure, aspiration, and self-realization. Hence, it is important to think of pleasure beyond its materiality and sensuality. Instead, we should use the sociality of pleasure to explore how its sensuality makes the other domains of human existence possible and meaningful.

Pleasure is also a resource and social capital. The acquisition of pleasure and attainment of pleasurable experience has always shaped the organization of labor, what is produced, and how these products are distributed, allocated, and consumed by individuals and different social groups. Pleasure as a resource is pertinent to the understanding of power and social inequity. Like every resource, pleasure is not evenly distributed, even when it is abundant. Therefore, pleasure is a “site” or “subject/object” of negotiation among individuals and social groups whose positionalities place them at different and unequal spectra of power relationships. It is central to the process of managing social relationships and hierarchies of power and authority, and of defining what those relationships mean. As an experiential phenomenon, it is through pleasure that the state, community, corporate, and individual identities are realized, created, and validated.

For this reason, any organized society is always preoccupied with the regulation of pleasure, things of pleasure, places of pleasure, and anatomies and senses of pleasure. This would explain, for example, why the mouth, legs, hands, eyes, genitalia, and vocal cords have been the most policed human anatomies in any society, past as well as present (Linden Reference Linden2011:4). Pleasure is a contested and negotiated locus of human interactions and a site for debating and establishing values. For example, Ọbàtálá’s ascetic and critical stance toward certain materialities and mores of pleasure offers an alternative vision of pleasure. Also, the Drinkard character in Tutuola’s novel is on a defiant one-person quest to circumvent the control of the production and distribution of pleasurable things, including the timing, organization, and management of the pleasure of palm-wine drinking. Drinkard jettisons work and drinks palm-wine all day as an over-indulged son of a rich man. Tutuola offers a different vision of pleasure in his novel, although one that violates the dominant morals of palm-wine consumption in his culture. This vision is fantastical, but it is also an allegory of social inequality, whereby the rich make merry all day while their laborers (such as the tapper) work all day. The dependency of the rich on their laborers is illustrated in Drinkard’s trouble and his quest to bring back his tapper from the land of the dead.

Those who determine what is pleasurable (and who can have it, or when) tend to be the ones who have control or, at the least, have situational authority in society (as the case of Drinkard shows). Hence, the sumptuary laws that governed who had the right to wear certain types of beads and who was allowed to eat horsemeat in ancient Yorùbá cities and towns, as well as the enforcement of certain calendars of festivals and cycles of work and pleasure, are central to maintaining social order. As a resource, pleasure is also a way of being and becoming, transforming human aspirations from one domain or level to the other. It accounts for much of what makes the life course dynamic and full of movement. Finally, pleasure as a freestanding subject tells us very little about human conditions. Its elasticity as a social concept is realized when we think of it in relation to everyday lives and its embeddedness in the ontology and epistemology of a community. As this and other articles in this issue show, there is more to explore about pleasure in Africa.

Acknowledgments

From the writing of the original conference paper on which this article is based to the post-conference revisions, Teju Olaniyan gave many encouraging words. I owe him immense gratitude for his generous and collaborative spirit, and for challenging me and others to imagine sources and data in new ways. I also thank all my collaborators and students who participated in the original research on which this article is based. Finally, my appreciation goes to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback, but I alone bear responsibility for any error that may be present in the article.