Introduction

Patient safety is a key priority for healthcare providers. However, it is estimated that up to 600 incidents occur daily in UK primary care (Esmail, Reference Esmail2013). A systematic review suggests that two to three safety incidents occur in every 100 consultations; 4% of these were associated with severe harm (Panesar et al., Reference Panesar, deSilva, Carson-Stevens, Cresswell, Salvilla, Slight, Javad, Netuveli, Larizgoitia, Donaldson, Bates and Sheikh2016).

Safety huddles, ‘brief, daily, focused team meetings involving all professional and clinical managerial staff in a non-judgmental setting’ (Cracknell, Reference Cracknell2017), are a well-established concept in high reliability organisations (Goldenhar et al., Reference Goldenhar, Brady, Sutcliffe and Muething2013). A systematic review of safety briefings in various healthcare settings suggests positive outcomes after safety huddle introduction, including improved risk identification, enhanced relationships, increased incident reporting and ability to voice concerns (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Ward, Vaughan, Murray, Zena, O’Connor, Nugent and Patton2019). In the United Kingdom, safety huddles have been introduced into secondary care with some promising early evaluation (Cracknell et al., Reference Cracknell, Lovatt, Winfield, Arkhipkina, Mcdonagh, Green and Rooney2016). However, the feasibility and acceptability of similar meetings in primary care are unknown and there have been no formal evaluations. We therefore explored the feasibility and acceptability of huddles in general practice.

Methods

Survey

We adapted an existing questionnaire on patient safety huddles (Alison Lovatt, personal communication, HUSH), which was based on the Theoretical Domains Framework (Michie et al., Reference Michie, Johnston, Abraham, Lawton, Parker and Walker2005) and the Improvement Academy’s Achieving Behaviour Change Toolkit (Yorkshire Quality and Safety Research Group, 2017), to use in general practice and refined questions on a convenience sample of general practitioners (GPs). We distributed the questionnaire electronically to all 314 practices in West Yorkshire (Supplementary Material, Appendix 1). We assessed findings using descriptive statistics.

Interviews

We sought interest from primary care professionals attending postgraduate meetings in Leeds during early 2018. We conducted semi-structured interviews based on the survey findings and exploring work schedules, meeting frequency and content, and individual’s experiences and views of safety huddles. We attempted to include a reasonably diverse sample of clinical and non-clinical staff from multiple practices. We initially planned to recruit a sample of around 20 participants and then judge the degree to which data saturation had been achieved.

We obtained written, informed consent prior to all interviews, which were recorded on an encrypted electronic device and transcribed verbatim. We used a framework approach to analysis. As the interviews were partially dictated by the findings of the survey, our a priori knowledge shaped the framework. One researcher (H.P.) familiarised herself with the transcripts, identifying issues and emerging concepts; sections of text were then coded, indexed and then charted into the framework. The coded concepts were subsequently interpreted (Srivastava and Thomson, Reference Srivastava and Thomson2009).

Results

In total, 34 general practices (practice response rate 11.1%) completed our survey, including 47 individuals participated with varying practice roles, duration of experience and sex (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of survey respondents

CCG – Clinical Commissioning Group.

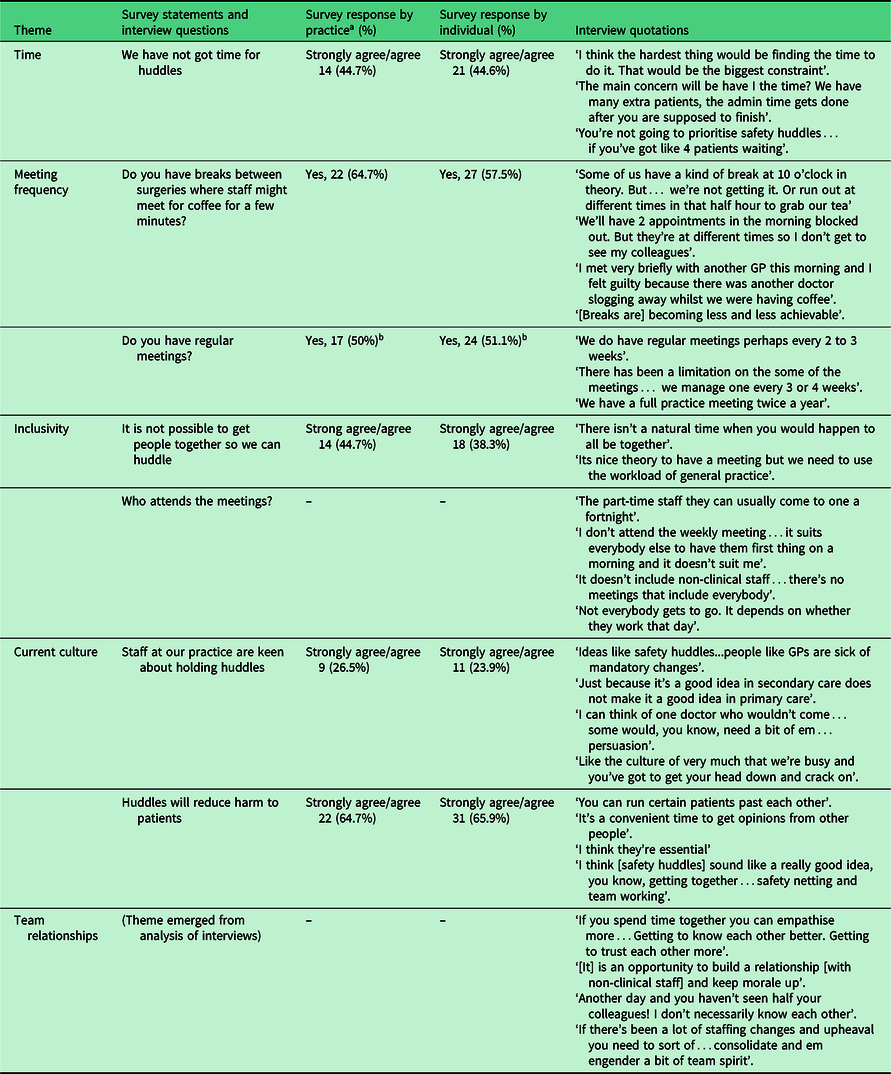

Twenty-two practices (64.7%) reported meeting for staff breaks, whilst eight (23.5%) reported that such meetings had ceased (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of survey and interview findings

a Counted as ‘yes’ for whole practice when over half of individuals from that practice responded yes.

b Includes daily, weekly and monthly meetings.

Lack of time was identified as the main barrier to adopting huddles and less than a third of respondents agreed they would be keen to start safety huddles (9; 26.5%).

In terms of facilitating factors more than half of the staff felt huddles may reduce harm (31; 65.9%); the majority of respondents felt they had the communication skills needed to contribute to huddles (41; 87.3%) and suitable places within the practice to huddle (32; 68.0%).

Seven professionals participated in interviews. Five key themes were identified: time, meeting frequency, meeting inclusivity, staff culture and relationships (Supplementary Material, Appendix 2).

Time. Consistent with survey findings, lack of time was the biggest barrier to either taking breaks or introducing safety huddles. Interviewees believed that time for breaks or meetings might be taken out of available appointments, meaning fewer patients would be seen or that clinics would overrun. There was an expectation that huddles or breaks would not be a priority in a busy system.

Meeting frequency. This varied, although no practice met more frequent than weekly. A variable staff working pattern, for example, working less than full-time, further hindered timetabling of meetings. Often this was tackled by meetings being on alternating days; however, this meant certain individuals were only able to attend a maximum of half all scheduled meetings and some could not attend any. Although some practices had a scheduled break, interviewees reported that, in reality, none of them managed this.

Inclusivity. Most practices had multiple meetings for different staff groups, for example, partners meetings, clinical meetings and practice meetings. Frequently, these meetings only included the clinical staff; others might include the practice manager but rarely other non-clinical staff such as receptionists. As with meeting frequency, less than full-time working patterns often prevented individuals from attending meetings.

Current culture. General practice was perceived by interviewees as a relatively isolating profession, with individuals working independently in separate rooms; this contrasts hospitals where multidisciplinary teams, physically working together, are the norm. Interviewees used this independent culture as an argument both for and against meetings and huddles. Interviewees believed introduction of huddles would be resisted due to the perception of them as a secondary care intervention, which would not fit with primary care working culture and structure. However, some individuals expected that meetings could provide clinical support within growing culture of GPs working in isolation.

Team relationships. Meetings and breaks can nurture team relationships and reduce conflict, particularly between individuals who do not work closely together. Scheduled meetings or breaks were perceived as important for newer employees and as clinical support networks. Interviewees also revealed the experience of guilt on casual interactions with colleagues, such as having coffee outside of allocated times. This is due to the experience that other colleagues may be unable to take a break that day and is closely related to the perception of workload, scheduling and time efficiency.

Discussion

Patient safety huddles appear promising in secondary care, but there are distinct challenges to their introduction in primary care. We identified time as the greatest barrier, along with workload pressures, and uncertainty about who should participate. Practice staff now appear to have fewer opportunities for meeting, but did recognise the potential professional and social value of huddles.

We believe that our modest, exploratory study is the first to assess the feasibility of huddles in UK primary care. However, our survey has not been validated for use in general practice and we only had limited time available for the interview study and recognise that we did not achieve data saturation. Our findings are susceptible to social desirability and respondent bias; we attempted to minimise the former by making the survey anonymous.

O’Malley et al. reported positive experiences in a small US primary care study, where 23 of 27 practices using huddles regularly perceived their value in enhancing staff communication (O’Malley et al., Reference O’Malley, Gourevitch, Draper, Bond and Tirodkar2015). Our interviewees generally considered that safety huddles were challenging to integrate within existing primary care time and resources.

Riley et al. identified that in a field where levels of stress and burnout are high, culture change and access to support are crucial to enable GPs to do their job effectively (Riley et al., Reference Riley, Spiers, Buszewicz, Taylor, Thornton and Chew-Graham2018). Currently, new opportunities for practices to meet are declining, which may have a perceived negative impact on practice relationships and contribute further to staff burnout (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Johnson, Watt and O’Connor2019).

General practice meetings are variable in terms of frequency and inclusivity. Overall, although staff are open to the idea of a huddle-type meeting, it is evident that the perceived positive benefits of team meetings are largely outweighed by the potential negative impact on other responsibilities. Given the small number of respondents in our study, we are cautious about its overall generalisability to UK general practice.

Any efforts to introduce huddles into general practice should consider tight time constraints and impact on staff morale, as well as sustainability. With growing evidence of individual pressure and burnout in GP (Riley et al., Reference Riley, Spiers, Buszewicz, Taylor, Thornton and Chew-Graham2018; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Johnson, Watt and O’Connor2019), further research into the role and feasibility of safety huddles is merited. Changing ways of working within general practices during the COVID-19 pandemic may add impetus to such work (Thornton, Reference Thornton2020; O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2020). However, the key litmus test will ultimately be whether huddles can be shown to improve patient outcomes, specifically the reduction of safety incidents in general practice.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423620000298

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Alison Lovatt at the Yorkshire and Humber Improvement Academy for providing the barriers to and enablers of huddles survey questions; Sam Stringer for organising recruitment at TARGET meetings; the West Yorkshire Research and Development team for their continued support and help throughout the project; the general practitioners at the Leeds Institute of Health Sciences for pre-testing our survey; and all participants of this research study for their time and contributions.

Author Contributions

R.F., C.H. and H.P. conceived and designed this study. C.H. and H.P. collected and analysed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in making further revisions and approving the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding

This work was supported by the Royal College of General Practitioners, Grant-SFB 2018-03.

Ethics

This study received ethical approval from the University of Leeds School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (MREC17-037) and approval from the Health Research Authority.