Nutrition researchers and dietitians are increasingly interested in supermarket environments( Reference Escaron, Meinen and Nitzke 1 – Reference Surkan, Tabrizi and Lee 6 ). Supermarkets, supercentres and grocery stores are the source of extra energy and sugars in the US diet( Reference Drewnowski and Rehm 7 , Reference Drewnowski and Rehm 8 ). A majority of low-income individuals using the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) spend their benefits at supermarkets and supercentres( Reference Castner and Henke 9 ). While supermarkets are generally regarded as ‘healthy’ elements of the community food environment( Reference Babey, Diamant and Hastert 10 ), within supermarkets consumers are inundated by marketing of both healthy and unhealthy foods and beverages( Reference Rivlin 11 ). Cognitive processes, including self-control or ‘individuals’ capacity to alter, modify, change, or override impulses, desires, and habitual responses’( Reference Baumeister 12 ), play an important role in how customers respond to marketing of unhealthy items. Customers who experience lower self-control may more easily succumb to marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages( Reference Vohs, Baumeister and Schmeichel 13 ), resulting in unhealthy, impulse purchases( Reference Salmon, De Vet and Adriaanse 14 ). Shopping behaviour is complex, and purchasing decisions are the result of both cognitive processes that occur in the store combined with food access issues at the community food environment level( Reference Baumeister, Sparks and Stillman 15 ). Because of disproportionately low access to healthy foods (the community food environment) among low-income and rural populations( Reference Morton and Blanchard 16 , Reference Larson, Story and Nelson 17 ), there have been increasing initiatives to build new supermarkets in underserved areas( Reference Holzman 18 ). However, such efforts have yielded minimal impact on improving dietary behaviours of residents( Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 19 – Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 ). In sum, healthy purchasing decisions can be hampered by barriers within the cognitive or psychosocial domain and physical access barriers within the community food environment domain, particularly among lower-income populations including SNAP and Special Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants, and Children recipients.

Grocery shopping in the 21st century is changing drastically, and one major element of this change is online grocery shopping( Reference Peregrin 2 ). In a Nielsen global survey of more than 30 000 consumers in sixty countries, approximately 10 % said they currently order groceries online and pick them up in-store or at the curbside. In addition, more than half said they would be willing to use these online options in the future, indicating the growing popularity of these online shopping options( 22 ). In the USA in 2015, online grocery sales were worth approximately $US 7 billion( 23 ). The Nielsen Global E-commerce and the New Retail Survey polled 30 000 online respondents in sixty countries and found that, worldwide, Millennials (age 21–34 years) and Generation Z (age 15–20 years) are the most frequent users of online grocery shopping (both home delivery and click-and-collect)( 22 ). Close to one-third (30 %) of Millennials and 28 % of Generation Z respondents to the Nielsen survey said they ordered groceries online for home delivery, compared with 22 % of Generation X (age 35–49 years), 17 % of Baby Boomers (age 50–64 years) and 9 % of Silent Generation (age ≥65 years) respondents. According to Nielsen, 55 % of North American consumers were willing and 12 % already used an online home delivery grocery service; and 57 % were willing and 9 % already used a service where groceries are ordered online and picked up at the store( 22 ). According to Euromonitor International’s Global Consumer Trends Survey, 25 % of Americans shopped for groceries online at least once in 2013, increasing to 38 % in 2016( Reference Grant 24 ).

However, little is known about individuals’ motivations for online grocery shopping and the potential promise and pitfalls related to online grocery shopping in terms of promoting healthier eating. Park et al.( Reference Park, Perosio and German 25 ) conducted a focus group discussion among consumers who had some experience with online grocery shopping and categorized participants into ‘Hi-Tech Baby Boomers’ and ‘Older/Physically Challenged Consumers’. ‘Hi-Tech Baby Boomers’ shopped for groceries online for convenience, whereas the ‘Older/Physically Challenged Consumers’ shopped for groceries online because of physical access barriers related to shopping at brick-and-mortar stores( Reference Park, Perosio and German 25 ). Hiser et al.( Reference Hiser, Nayga and Capps 26 ) found that younger, more highly educated consumers would be more likely to be online shoppers compared with older and less educated consumers. In another study, convenience was the primary motivator for shopping online( Reference Morganosky and Cude 27 ). Other motivating factors included physical constraints, the presence of children, a more peaceful shopping experience, easier monitoring of total spending and more opportunities for planning( Reference Morganosky and Cude 27 ). Constructs from behavioural theories such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour( Reference Ajzen 28 ) could also be applied to explaining online shopping behaviour( Reference Hansen 29 ), including attitudes towards the behaviour (the positive and negative perceptions of online shopping), subjective norms (perceived social pressure to perform the behaviour) and perceived behavioural control (perceptions of ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour).

Given this prior work, when juxtaposed with in-store shopping, online grocery shopping has the potential to dramatically limit the impact of both the cognitive barriers to healthy food access as well as community access barriers related to healthy food purchase within the supermarket food environment: consumers can shop online at any time and online grocery shopping allows low-income food desert dwellers and customers with limited mobility to order groceries online and have them delivered( Reference Appelhans, Lynch and Martin 30 ). While online grocery shopping offers potential solutions to many healthy food access challenges, there are potential pitfalls that need to be better understood. For example, with online shopping, retailers have ready access to customer data on purchasing patterns( Reference Yuan, Pavlidis and Jain 31 ) and thus can target marketing to these customers. Once purchased, items usually remain on an individual’s past purchasing ‘list’ and thus are regularly seen by the customer, which could turn an unhealthy ‘once in a while’ treat into a pervasive prompt for more frequent purchases. In addition, the ease of online grocery shopping could lead to over-purchasing and, subsequently, overconsumption.

Therefore, the objectives of the current scoping review included: (i) to determine the current state of online grocery shopping, including individuals’ motivations for shopping for groceries online and types of foods purchased; and (ii) to identify the potential promise and pitfalls that online grocery shopping offers related to food and beverage purchases. We specifically examined factors related to: (i) motivations for online grocery shopping; (ii) the cognitive/psychosocial domain, including the role of impulse purchases and nutrition information on products; and (iii) the community food environment domain and alleviation of rural and urban food access issues.

Methods

We selected the scoping review methodology because online grocery shopping is a relatively new and growing phenomenon in the USA and we wanted to learn more about the ways it could encourage or hinder healthy purchasing decisions. We felt a scoping review methodology was preferable to a systematic review as we wanted to address online shopping from a broader perspective, including studies from a wide variety of disciplines and using both qualitative and quantitative research designs( Reference Dijkers 32 , Reference Arksey and O’Malley 33 ). Below we list the Arksey and O’Malley( Reference Arksey and O’Malley 33 ) steps and methodology used to our literature review.

Framework stage 1: Identify the research question

Our research question was: ‘What is known from the existing literature about online grocery shopping as it pertains to the (i) cognitive/psychosocial domain, including impulse purchases and provision of nutrition information for grocery products, and (ii) the community food environment domain including alleviation of rural and urban food access issues?’

Framework stages 2 and 3: Identifying relevant studies and study selection

In October and early November 2017, we searched for studies published in English, on or after 2007, and based in the USA or Europe. Papers were eligible if they were: peer-reviewed, published in English between 2007 and 2017; based in the USA or Europe; and focused on motivations for online grocery shopping, the cognitive/psychosocial domain (particularly impulse purchases and nutrition information/marketing on products) or the community food environment domain (alleviating healthy food access problems and barriers). The main reasons for exclusion were that studies were not conducted in the USA or Europe, or not focused on the topic areas of interest.

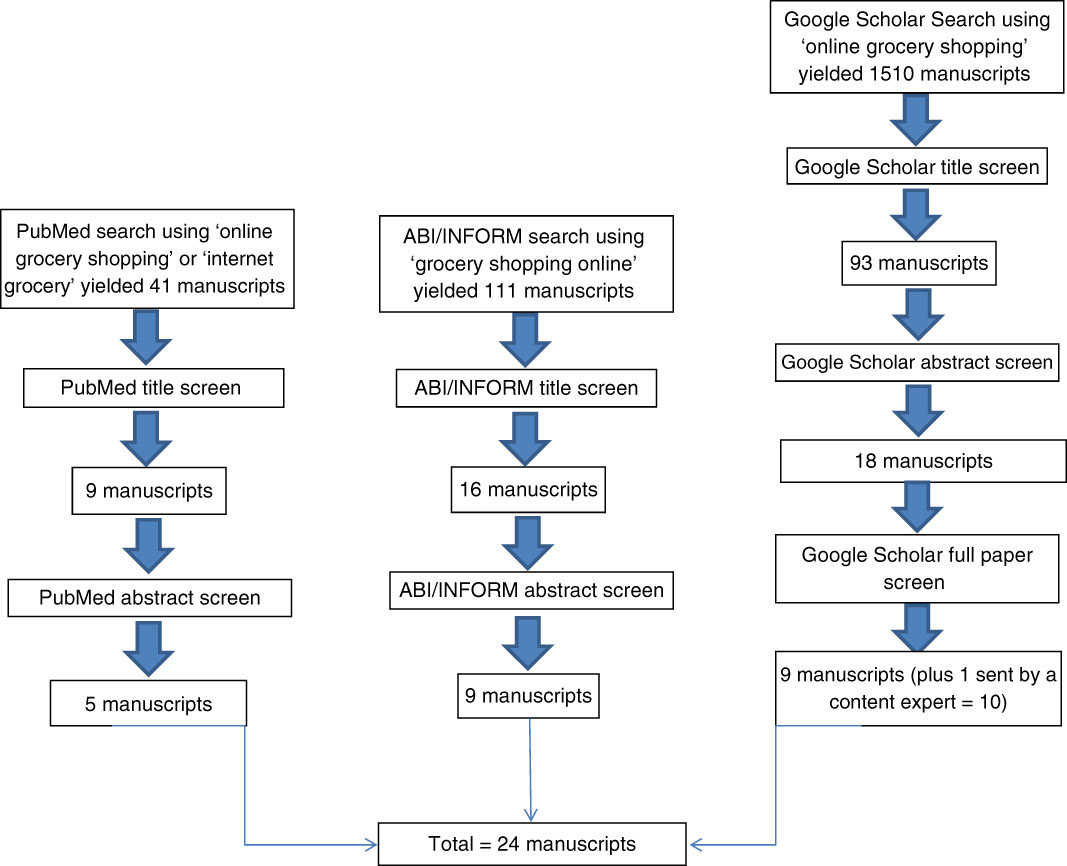

In PubMed, we used the search terms ‘online grocery shopping’ or ‘internet grocery’ which yielded forty-one manuscripts. The first author (S.B.J.P.) screened each title and nine were potentially applicable papers for an abstract screen. The first author screened all abstracts before deciding which should be included in the review. The main reason papers were excluded was because they were not related to the topic (e.g. titles such as ‘Use of a text message program to raise type 2 diabetes awareness and promote healthy behavior change’ and ‘Reference-based pricing: an evidence-based solution for lab services shopping’). After the abstract screen, five were deemed applicable to include in the review. Of the four excluded, two were set outside the USA and Europe( Reference Dixon, Scully and Wakefield 34 , Reference Machín, Arrúa and Giménez 35 ), one was a perspectives piece( Reference Peregrin 2 ) and one was about online store coupons (not online grocery shopping)( Reference Lopez and Seligman 36 ).

We searched ABI/INFORM for marketing and consumer behaviour studies, using the search term ‘grocery shopping online’, and limited the search to peer-reviewed papers. This yielded 111 peer-reviewed papers. The first author screened each title and selected sixteen potentially applicable papers for the abstract screen. The main reasons papers were excluded during the title screen were not being based in the USA or Europe, not related to the main research questions (e.g. related to personal privacy as a positive experience of grocery shopping), being about supply chain management topics and not specifically about online grocery shopping (but about online shopping in general). The abstract screen yielded nine papers for inclusion in the review. Of the seven excluded at the abstract screen, four were excluded due to not being based in the USA or Europe( Reference Sreeram, Kesharwani and Desai 37 – Reference Bhardwaj and Sharma 40 ) and three were excluded due to not being about the topic areas of interest( Reference Fiore and Kelly 41 – Reference Mortimer, Fazal e Hasan and Andrews 43 ).

Google Scholar ‘advanced search’ was used to find any potentially relevant papers that would not be indexed in PubMed or ABI/INFORM. The search included the exact phrase ‘online grocery shopping’ between 2007 and 2017. There were 1510 hits (excluding citations and patents). The first author title-screened each paper and added relevant papers to the list for the abstract screen. There were 104 papers identified for inclusion, of which eleven were identified as duplicates from PubMed or ABI/INFORM, leaving ninety-three papers for the abstract screen. The main reasons for exclusions were unpublished papers (e.g. theses or conference proceedings), not based in the USA or Europe, and not about the topic area. There were eighteen papers selected for the full paper screen and nine were selected for inclusion. One additional paper, published online in early December 2017, was forwarded to the authors by a colleague and content expert, and included in the review( Reference Martinez, Tagliaferro and Rodriguez 44 ). The reasons for exclusions during the full paper screen included papers not being peer-reviewed( Reference Cebollada 45 , Reference Chintagunta, Chu and Cebollada 46 ) (including two that were chapters in eBooks)( Reference Wriedt 47 , Reference Zhu and Semeijn 48 ) and not about the topic area( Reference Arce-Urriza and Cebollada 49 – Reference Zhang and Breugelmans 51 ). See Fig. 1 for a flow diagram of the review process.

Fig. 1 (colour online) Flow diagram of the study selection process for the present review of online grocery shopping

A second author (J.B.) conducted an abstract/full paper screen on 20 % of the papers found in each search engine, with authors agreeing on 92 % (22/24) of the reviewed abstracts. Due to the screening process, further two papers were eliminated from the review, as they were focused more on the use of front-of-package nutrition labelling (while using a simulated supermarket)( Reference Ducrot, Julia and Méjean 52 , Reference Graham and Jeffery 53 ) rather than the utility of various marketing strategies in the online grocery shopping environment.

Framework stages 4 and 5: Charting the data, and collating, summarizing and reporting the results

Each study was entered into a table describing the study setting, location, population and findings, with special emphasis on findings related to the topic areas of interest as stated above. A final column on the table specified implications related to online grocery shopping’s potential pitfalls and promise for encouraging healthy food and beverage purchases. Data were synthesized for each area of interest in the cognitive and physical access domains, drawing out implications for future research, policy and practice.

Results

We reviewed and summarized a total of twenty-four peer-reviewed papers (Table 1). We organized the results related to the following themes: (i) motivations for adoption of online grocery shopping, and types of foods and beverages purchased; (ii) the cognitive/psychosocial domain, including the role of impulse purchases and nutrition information on products; and (iii) the community food environment domain and alleviation of rural and urban food access issues. Below we highlight the main results from across the twenty-four papers by theme.

Table 1 Overview of literature reviewed related to online grocery shopping and impulse purchases, stimulus control, pester power and community food access

SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; EBT, electronic benefit transfer.

Motivations for adoption of online grocery shopping

In terms of motivation for beginning online shopping, convenience and saving time were noted as motivations in several studies( Reference Hand, Dall’Olmo Riley and Harris 54 – Reference Campo and Breugelmans 57 ). In addition, life events such as caring for a sick family member or transitioning to a new residence were also reasons for online grocery shopping( Reference Hand, Dall’Olmo Riley and Harris 54 , Reference Elms, De Kervenoael and Hallsworth 58 , Reference Robinson, Dall’Olmo and Rettie 59 ). Avoiding crowds in long lines in supermarkets and the ability to multitask while shopping were also reasons for engaging in online grocery shopping( Reference Harris, Harris and Dall’Olmo 56 , Reference Elms, De Kervenoael and Hallsworth 58 ). In a study among Belgian shoppers, those with higher education in households with young children where both adults were working were more likely to adopt online grocery shopping( Reference Van Droogenbroeck and Van Hove 60 ). Hansen et al. found that constructs of the Theory of Planned Behaviour were related to willingness to purchase groceries online, including social norms and perceived behavioural control( Reference Hansen 29 ). Studies noted that participants rarely switched to online grocery shopping for 100 % of grocery shopping needs and generally conducted in-store grocery shopping with some frequency( Reference Ramachandran, Karthick and Kumar 55 , Reference Harris, Harris and Dall’Olmo 56 , Reference Elms, De Kervenoael and Hallsworth 58 , Reference Melis, Campo and Breugelmans 61 , Reference Chu, Arce-Urriza and Cebollada-Calvo 62 ).

Barriers to online grocery shopping included the inconvenience of waiting for deliveries, delivery fees, orders not being filled appropriately, and inappropriate or inadequate substitutions( Reference Hand, Dall’Olmo Riley and Harris 54 – Reference Harris, Harris and Dall’Olmo 56 , Reference Elms, De Kervenoael and Hallsworth 58 , Reference Robinson, Dall’Olmo and Rettie 59 ). In addition, consumers tend to be less price-sensitive and are less likely to comparison shop when in the online v. in-store environment( Reference Chu, Arce-Urriza and Cebollada-Calvo 62 ).

Types of foods purchased

Shoppers are hesitant to purchase perishable items via online grocery shopping and preferred to purchase fresh, perishable items in brick-and-mortar stores( Reference Elms, De Kervenoael and Hallsworth 58 , Reference Clark and Wright 63 ). Items such as bulky detergents, diapers and other household goods were frequently purchased online( Reference Campo and Breugelmans 57 , Reference Robinson, Dall’Olmo and Rettie 59 ). The ‘favourites’ list was a helpful resource for some online grocery shoppers( Reference Robinson, Dall’Olmo and Rettie 59 , Reference Clark and Wright 63 ).

Impulse purchases

Impulse purchases are made less frequently in the online v. off-line modality( Reference Ramachandran, Karthick and Kumar 55 – Reference Robinson, Dall’Olmo and Rettie 59 , Reference Clark and Wright 63 – Reference Gorin, Raynor and Niemeier 66 ). In an ethnographic study( Reference Elms, De Kervenoael and Hallsworth 58 ), one participant noted his distaste of how supermarkets are designed to maximize impulse purchases and how grocery shopping online was beneficial to avoid such impulse purchases. However, in another study, participants viewed the opportunity to make impulse purchases positively, as a way to get ideas for meals while in the store( Reference Harris, Harris and Dall’Olmo 56 ). Two studies noted that online shopping resulted in avoidance of unhealthy ‘vices’( Reference Huyghe, Verstraeten and Geuens 65 ) or ‘want’( Reference Milkman, Rogers and Bazerman 64 ) groceries in favour of more ‘virtuous’ or ‘should’ foods and beverages.

Nutrition information on products

Six studies were focused on promotion of healthy foods or warnings regarding unhealthy foods within simulated or existing ‘real’ online supermarket environments( Reference Campo and Breugelmans 57 , Reference Benn, Webb and Chang 67 – Reference Forwood, Ahern and Marteau 71 ). In terms of promoting foods via online supermarket displays, the ‘first screen’ displays were the most powerful for increasing product choice in one study( Reference Breugelmans and Campo 68 ). In an eye-tracking study( Reference Benn, Webb and Chang 67 ), investigators found that only a small proportion of fixations were focused on nutrition information. They also found that even having a restricted diet (e.g. weight-related or allergy-related) did not influence how often participants looked at nutrition or ingredients information( Reference Benn, Webb and Chang 67 ), suggesting that more steps should be taken in the online grocery shopping environment to encourage consumers to view nutrition-related information. In an innovative study which offered lower-calorie within-category ‘swaps’ for higher-calorie options, there was some evidence of the lower-calorie ‘swaps’ improving the healthfulness of purchases( Reference Forwood, Ahern and Marteau 71 ).

Alleviation of rural and urban food access issues

Four studies examined the feasibility of using online grocery shopping to alleviate food access problems( Reference Appelhans, Lynch and Martin 30 , Reference Martinez, Tagliaferro and Rodriguez 44 , Reference Gorkovenko, Tigwell and Norrie 72 , Reference Lagisetty, Flamm and Rak 73 ). These studies generally found that it is a feasible method, with a few caveats. First, to increase access among low-income groups, there is a great need to ensure that online grocery stores accept federal food assistance benefits and have delivery timelines that meet customers’ needs( Reference Appelhans, Lynch and Martin 30 , Reference Martinez, Tagliaferro and Rodriguez 44 , Reference Gorkovenko, Tigwell and Norrie 72 , Reference Lagisetty, Flamm and Rak 73 ). It is noteworthy that Martinez et al.( Reference Martinez, Tagliaferro and Rodriguez 44 ) were not able to analyse data from their randomized controlled trial owing to the fact that only three of 166 participants randomized to the online shopping condition actually completed follow-up measures. In focus group discussions, the researchers found that SNAP/electronic benefit transfer (EBT) customers preferred being in control of the shopping experience, and wanted to be able to see, touch and smell perishable items purchased using SNAP/EBT( Reference Martinez, Tagliaferro and Rodriguez 44 ). Second, to expand access among older populations, there is a need to address concerns related to exchanging financial information over the Internet( Reference Gorkovenko, Tigwell and Norrie 72 ). Third, in rural settings, there is a need to expand home delivery options, with one study noting that rural consumers may opt for online grocery shopping to avoid the long commute to grocery stores( Reference Lennon, Ha and Johnson 74 ).

Table 2 summarizes the potential promise and pitfalls of online grocery shopping along the cognitive/psychosocial and the community food access domains. A few potentially promising strategies include increased healthy habit and meal planning through use of a list function online( Reference Robinson, Dall’Olmo and Rettie 59 , Reference Clark and Wright 63 ) and fewer impulse purchases( Reference Huyghe, Verstraeten and Geuens 65 , Reference Gorin, Raynor and Niemeier 66 , Reference Lagisetty, Flamm and Rak 73 ), emphasizing front-of-package labelling and marketing to emphasize healthy options in the online environment( Reference Wolfson, Graham and Bleich 50 , Reference Benn, Webb and Chang 67 ), and offering free trials of perishable items online to reduce perceived risk( Reference Campo and Breugelmans 57 ). Potential pitfalls include the fact that customers are not as likely to purchase perishable items (like fruits and vegetables) online( Reference Martinez, Tagliaferro and Rodriguez 44 , Reference Elms, De Kervenoael and Hallsworth 58 , Reference Clark and Wright 63 ), consumers are less price-sensitive( Reference Chu, Arce-Urriza and Cebollada-Calvo 62 ) and may not view nutrition information online( Reference Benn, Webb and Chang 67 ).

Table 2 Summary of potential promise and pitfalls of online grocery shopping to promote healthy food purchases among low-income US residents along the cognitive/psychosocial and community food environment domains

SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Discussion

Our findings regarding factors that motivate online grocery shopping were similar to what has been found by others in prior studies that were conducted before 2007 (outside the scope of our review). For example, Park et al. found that ‘Hi-Tech Baby Boomers’ were motivated by convenience and ‘Older/Physically Challenged Consumers’ shopped online due to physical barriers related to shopping at brick-and-mortar stores( Reference Park, Perosio and German 25 ). In another study, convenience was the primary motivator for shopping online( Reference Morganosky and Cude 27 ). These results are in agreement with papers in the current review, which found evidence to suggest that shoppers are motivated by convenience and the ability to save time( Reference Hand, Dall’Olmo Riley and Harris 54 – Reference Campo and Breugelmans 57 ), avoid crowds and multitask while shopping( Reference Harris, Harris and Dall’Olmo 56 , Reference Elms, De Kervenoael and Hallsworth 58 ).

Online grocery shopping offers potential promise to promote healthier food and beverage choices, including fewer impulse purchases( Reference Chintagunta, Chu and Cebollada 46 , Reference Campo and Breugelmans 57 , Reference Huyghe, Verstraeten and Geuens 65 , Reference Gorin, Raynor and Niemeier 66 ), and greater access to healthy foods (through the Internet), even when such foods are less available in the physical environment( Reference Appelhans, Lynch and Martin 30 ). However, online grocery shopping is not without its potential pitfalls. Consumers may be less likely to use online grocery shopping to make perishable food purchases (e.g. fresh fruits, vegetables, meats)( Reference Elms, De Kervenoael and Hallsworth 58 , Reference Clark and Wright 63 ) due to concerns about freshness, bruising and food safety( 22 , Reference Freud 75 ). This could lead to less healthy purchasing habits being cultivated by the online grocery shopping experience, as customers not only have healthy options, but also several unhealthy processed foods easily available in the online environment. Others found that customers purchased more bulk/heavy items online v. in stores( Reference Campo and Breugelmans 57 ). Appelhans et al.( Reference Appelhans, Lynch and Martin 30 ) found that among participants provided with a Peapod voucher for online shopping, the majority used at least some of the voucher for purchasing meats, fruits and vegetables, suggesting that consumers will purchase fresh foods online. Moreover, packaged frozen, canned and dried fruits and vegetables could be promoted to increase fruit and vegetable consumption( 22 , Reference Freud 75 ). Additional research is needed to understand how to encourage purchases of healthy, fresh foods online, given consumers’ concerns about perishability, refrigeration and storage.

Limitations of the current review include potential for publication bias, lack of assessment of study quality for all studies included and the potential to miss important papers in the field. However, we attempted to minimize missing papers in the field by searching multiple databases and including a second abstract screener. Furthermore, due to technical error, we used similar but not identical search terms across different search engines. All searches included the terms ‘online’, ‘grocery’ and ‘shopping’, but the order of terms was changed. Strengths include a very inclusive search strategy, inclusion of marketing and public health nutrition literature, and a systematic method of characterizing studies.

Conclusions and implications

Reducing unhealthy impulse purchases through online grocery shopping could promote better dietary practices and health( Reference Milkman, Rogers and Bazerman 64 , Reference Huyghe, Verstraeten and Geuens 65 ). Providing labelling and online shopping in-store displays( Reference Breugelmans and Campo 68 , Reference Epstein, Finkelstein and Katz 70 ) to promote healthier foods online might be one way public health nutrition and marketing and retailers could intersect to both promote health and increase purchase of produce and other fresh items online. As few of the studies we reviewed focused on low-income consumers specifically, online grocery shopping should be studied further particularly among lower-income consumers, to determine how federal food assistance policies can be shaped to promote healthy purchases in the online grocery shopping environment. If online grocery shopping can contribute to healthier food and beverage purchase and consumption, it could be one mechanism to promote healthful purchases among low-income participants. Currently, the US Department of Agriculture is piloting SNAP/EBT online grocery purchase at seven retailers (Amazon, FreshDirect, Safeway, ShopRite, Hy-Vee, Hart’s Local Grocers, Dash’s Market) in eight states (Iowa, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Washington)( 76 ). It will be interesting to observe how consumers respond to this opportunity and the healthfulness of their resultant purchases.

We did not review the literature related to home delivery services that provide the ingredients and recipes to make one meal (meal kits), which could potentially be leveraged to promote healthier consumption among low-income and disadvantaged consumers but were considered outside the scope of our narrative review. Given that these meal kits often involve perishable ingredients, such services could provide insights on how to encourage purchase and consumption of perishable and healthier groceries and how to best keep perishable foods looking attractive and fresh.

In conclusion, the present scoping review summarizes some key considerations and questions for future research as well as promising and innovative practice to maximize the promise of online grocery shopping, while minimizing the risks, to successfully promote improved nutrition among all sectors of society.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank Aleah Johnston and Caroline Price for their work on organizing information for this review. Financial support: The authors wish to acknowledge Healthy Eating Research, a national programme of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, for supporting this Commissioned Review on Online Grocery Shopping. Healthy Eating Research, a national programme of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, was involved in the initial scoping of the research question, but had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: S.B.J.P. led this review as an independent consultant. Authorship: S.B.J.P., S.W.N. and J.B. conceived the study, S.B.J.P. conducted the searches, and S.B.J.P. and J.B. conducted screening for study inclusion/exclusion. All authors contributed to literature review design, critiqued the paper for critical intellectual content and approved the manuscript as submitted. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.