While successfully tackling the challenge of food security in Europe, the dramatic evolution of the food system since World War II has led to a well-recognized increase of nutrition-related diseases( 1 ). Food supply has increased beyond population needs, often driven by production subsidies, particularly on animal source foods. Dietary choices are influenced more by the supply and marketing of food performed by the food industry, the advertising and retail sector and the media, than by nutrition recommendations( 2 ). In addition, lifestyle, technological changes and urban design have discouraged active transport and physical activity, both at work and in leisure time.

Unhealthy diets and physical inactivity are evidently related to overweight and obesity and present major risk factors for non-communicable diseases, of which the WHO European Region is the most afflicted in the world( 3 ). Overweight affects between 30 % and 80 % of adults in the WHO European Region and up to one-third of children( 4 ).

On the other hand, deficiencies in micronutrients such as Fe, iodine, vitamin A and folate are widespread in the Region. Fe deficiency affects growth retardation and has increased in the Central Asian Republics and is also a concern in the other newly independent states, where 32–70 % of children under 5 years of age are affected( 5 ). A total of 435 million people in the European Region are affected by iodine deficiency( 6 ).

Nutrition policies should address this double burden of malnutrition through the prevention of diet-related diseases, a sustainable and safe food supply, and the integration with related risk factors. The basis for the global development of nutrition policies was provided by the 1992 World Declaration on Nutrition and Plan of Action on Nutrition( 7 ). The next major step in the European Region was the adoption of the First WHO Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy in 2000, which further encouraged Member States to develop food and nutrition policies combining nutrition, food safety and food security and sustainable development into an overarching, intersectoral policy( 8 ).

In response to the global epidemic of chronic, non-communicable diseases, the WHO Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health was adopted in 2004 to strengthen existing national, regional and international efforts to prevent and control chronic diseases and their common risk factors( 9 ).

In order to facilitate Region-wide action on the emerging public health challenge of obesity, the WHO European Charter on Counteracting Obesity was adopted in 2006( 10 ). One of the steps to implement the Charter was the development of the Second WHO European Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy, endorsed in September 2007.

In the European Union (EU), a series of council resolutions addressing nutrition was adopted in 1990( 11 ), 2000( 12 ), 2002( 13 ) and 2005( 14 ), emphasizing the importance of placing nutrition on the agenda. In 2007, the European Commission adopted the White Paper called A Strategy for Europe on Nutrition, Overweight and Obesity Related Health Issues, setting out a wide range of proposals on how the EU can tackle nutrition, overweight and obesity-related health issues( 15 ).

The present paper aims at describing the current status of nutrition policy in the WHO European Region. The different levels of policy development are analysed using a novel approach by mapping nutrition policy developments. The paper further aims to describe specific elements of existing policies, to identify common elements of successful policies and to discuss implications of the different policy patterns on public health.

Methods

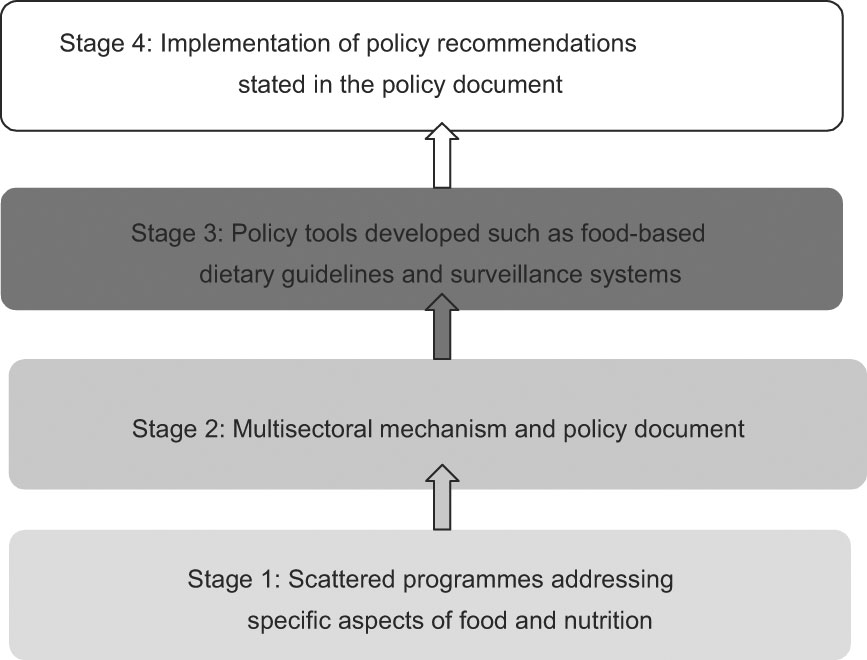

The nutrition and food security programme of the WHO Regional Office for Europe has conducted surveys on national nutrition policy in European Member States in 1994–5, 1998–9 and 2003( 16 – 18 ). Questionnaires were sent to nutrition counterparts in health ministries. Thirty-three out of fifty countries responded to the first questionnaire; forty out of fifty countries responded to the second; and the questionnaire from 2003 was returned by forty-eight out of fifty-two. In 2005, Member States were contacted again; eighteen returned an updated questionnaire and an additional questionnaire was obtained from Cyprus, which had joined the Region in the mean time. The questionnaire included questions on policy documents, institutional capacities, intersectoral collaboration, dietary reference values and food-based dietary guidelines, and monitoring and evaluation( 18 ). Based on the findings of the survey in 2005 and on observations of policy development patterns from previous analysis( 16 – 18 ), countries were classified according to three stages of policy development, indicating the increasing complexity and attention to implementation. This step approach was also used as a basis for the implementation of the Second WHO European Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy 2007–2012. In order to visualize these stages, a score was developed using collected information on policy mechanisms (policy document, intersectoral collaboration mechanism) and policy tools (food-based dietary guidelines and regular surveillance systems on dietary intake and weight and height).

At each stage, the elements of the previous stage were presumed to be present (Fig. 1): at stage 1, the presence of programmes addressing specific aspects of food and nutrition (score: 0–1); at stage 2, the presence of a multisectoral mechanism and a policy document related to nutrition (score: 0–2); at stage 3, the presence of policy tools such as food-based dietary guidelines and surveillance systems on dietary intake and weight and height (score: 0–3).

Fig. 1 Stages of nutrition policy development

In addition, fifty policy documents from thirty-three countries that were published by national bodies in Danish, Dutch, English, French, German, Italian or Norwegian were analysed. An analytical framework was elaborated to analyse the policy documents adapted from elements used in previous policy analyses( 19 –Reference Crombie, Irvine, Elliott and Wallace 21 ) and policy analysis tools(Reference Busse and Schlette 22 ). Using ANGELO as a basis(Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza 23 ), activities were divided into microenvironment (schools, workplaces and health-care services) and macroenvironment (urban planning and transport and the food supply sector).

The documents are either specific food and nutrition action plans or overall public health or environmental strategies with a nutrition component. Additional information and details about national nutrition policies were obtained from recent publications, various web sites of national health and environment ministries and health agencies.

Information and documents from Member States was collected until June 2007.

Results

National policy development

The adoption of a food and nutrition policy by the government or parliament should provide the basis for political commitment and enable public health institutions to transfer policy into action. The process of adoption varies in Member States, and in some countries policies are implemented and actions are taken even without a formal adoption process.

Norway was the first country in the WHO European Region with an approved nutrition policy in 1975, followed by Denmark, Finland, Iceland and Sweden, where political commitment towards nutritional issues was achieved in the 1980s( 24 ).

In 2003, twenty-five countries stated to have a final government-approved policy document concerned with nutrition, a number that increased in 2005 to thirty-seven countries having a final and adopted document. At present, there are forty-six countries with a policy document in a final or at least draft version.

In the 2005 survey, twenty-eight Member States stated that the First WHO European Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy had a significant impact on the development of national nutrition policies. Since 2000, thirty-eight countries have developed new policy documents or revised existing documents. Some countries reported not having a separate and finalized nutrition action plan, but having individual programmes in place addressing micronutrient deficiencies such as iodine deficiency disorders and Fe-deficiency anaemia (Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan); or the promotion of breast-feeding (Azerbaijan and Tajikistan) or food safety and food security in particular (the case in Armenia, Belarus and Kyrgyzstan)( 18 ).

The list of policy documents dealing with nutrition is provided in Table 1( 25 – 74 ).

Table 1 National policy documents related to food and nutrition

*Documents which were included in the analysis.

Institutional capacity

The presence of a national coordination body, such as a food and nutrition council, allows governments to develop, implement, monitor and evaluate nutrition policies, guidelines and action plans. Such institutes are often more than just a technical advisory body, acting as a gateway between evidence and policy and examining obstacles to policy coherence(Reference Lang, Rayner, Rayner, Barling and Millstone 75 ).

At present, thirty-seven countries have an advisory body compared with twenty-eight countries in 1998–9. In most cases the health or public health ministry funds the activities of the scientific advisory body.

In Scandinavia nutrition councils were established very early: the first recorded councils were created in Norway in 1937 and in Finland in 1954( 24 ). The Norwegian National Nutrition Council is responsible for establishing guidelines for food supply and nutrition policy to promote public health and to encourage agriculture. The tasks of the Finnish national council, for instance, are to submit proposals to the authorities, observe and monitor the developments of nutrition issues, and implement the nutrition recommendations.

Twenty-six Member States have established food safety agencies, authorities or institutes to coordinate national food safety activities, to set up food standards and/or to separate risk assessment from risk management responsibilities.

Administrative structures that are responsible for implementation and coordination are in place in forty countries. Most countries stated the ministry of health or related ministries are responsible for the implementation of the national policies. In some countries as in the Baltic and Nordic region there is a specific body responsible for the implementation of nutrition policies.

Thirteen of the forty implementing bodies were referred to as being effective, nineteen countries indicated their administrative structures were partly effective and four bodies were reported not to be effective. The reasons mentioned for non-effective bodies were lack of financial support, followed by lack of coordination, lack of political support and lack of expertise. Other reasons included insufficient legislation and lack of scientific basis due to lack of information from surveys.

Additional to a general food and nutrition institution, more and more countries are creating an institution specifically responsible for the prevention of obesity, such as the Czech Republic and Ireland.

Intersectoral collaboration

Nutrition-related health problems are multifactorial, calling for an involvement of different stakeholders and an intersectoral approach on the national, local and community level. One of the first steps in developing an effective food and nutrition policy is to ensure good collaboration between them( 76 ).

Stakeholders are ministries of health, agriculture, education, economy, finance, sport, social affairs and transport as well as other governmental institutions. In many countries, the ministry of health takes a leading role in the intersectoral collaboration.

Thirty-one countries collaborate at a ministerial level. In twenty-two countries nutrition issues are discussed with intersectoral effort, not only with different ministries but also with food industry and non-governmental organizations. There are five countries that stated not to collaborate with other sectors due to frequent changes in ministries, lack of coordination, changes in political situation and lack of clearly defined responsibilities.

Countries use different strategies in identifying the stakeholders. For instance, for the Spanish strategy for nutrition, physical activity and prevention of obesity, various collaboration agreements were signed with a wide range of stakeholders for different issues( 66 ). The Netherlands Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport created a Covenant on Overweight and Obesity with partners in the government and the private sector( 55 ). In the UK local strategic partnerships bring together local authorities, public services and private and community organizations and work together with residents( 73 ). Recently also Italy and Portugal have set up platforms to tackle obesity in collaboration with different stakeholders( 77 ).

Dietary reference values and food-based dietary guidelines

Forty-four countries stated to have dietary reference values available, although more than half of the countries are using reference values developed by the EU, WHO or other countries. The Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland and Norway) published joint Nordic nutrient recommendations( 78 ), as did three German-speaking countries, Austria, Germany and Switzerland (D-A-CH nutrient reference values)( 79 ).

Translating reference values into food-based dietary guidelines is important to make them understood by the general population. At present, forty countries report having food-based dietary guidelines, six more than observed in a survey conducted in 2002. Most of the countries use nutrition pyramids, circles or plates as graphic models. Additionally, Armenia and Uzbekistan are developing national food-based dietary guidelines.

Monitoring and surveillance

Data on health indicators are essential for comparing development in countries, for monitoring dietary intake and nutritional status of the population, for evaluating the impacts of interventions and for providing information for political decision making( 80 ).

Individual dietary intake data of adults were available from forty Member States; thirty countries undertook surveys on adults and only about half of the countries conducted surveys for the elderly, adolescents, children and infants. Among the methods used, the FFQ and the 24 h recall were the most frequently used. Some countries also rely on data from household budget surveys, and others are retrieving information of dietary intake from food balance sheets, which show the per capita food supply and not the individual food consumption.

In twenty-four countries, dietary intake in adults is monitored on a regular basis with a time interval of 1–10 years. Regular surveys on infants, children, adolescents and the elderly are conducted in about twelve countries, with an interval range of 1–16 years.

As overweight and obesity pose a dramatic threat in the European Region, regular monitoring of weight and height is essential to observe the trend and measure the effectiveness of national obesity strategies.

National representative data from adults on weight and height are available in forty countries, having several limitations, such as broad collection periods and in twenty-five national surveys weight and height are not measured, but self-reported( 81 ).

Twenty-four countries carry out regular weight and height surveys on adults at intervals of 1–10 years (TMA Wijnhoven and F Branca, unpublished results). About fifteen countries reported to regularly monitor weight and height of the elderly, children and infants with intervals of 1–15 years( 18 ).

Analysis of the stage of policy development

Member States are at different stages of food and nutrition policy development (Fig. 2). As also shown in previous policy analyses( 16 – 18 ), prior to developing national coordinated nutrition policies, countries appear to have individual programmes in place addressing particular public health nutrition challenges such as micronutrient deficiencies, breast-feeding or food insecurity (stage 1), which is currently the case in two countries. An additional nine countries already have a draft policy document available, but no institutional capacity for implementing and coordinating the policies. The following step of policy development should be to establish or to strengthen a public multisectoral mechanism to assist in effective coordination and intersectoral action (stage 2). The development of a policy document could be one of the tasks of such a mechanism. Most of the countries (n 37) in the European Region have reached stage 2.

Fig. 2 Policy development stages (▓, stage 3 fully achieved; ▒, stage 2 fully achieved, stage 3 partly achieved; ░, stage 1; ␣, no information) in the WHO European Region. The designations employed and the presentation of this material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delineation of its frontiers or boundaries

Developing tools to facilitate the implementation would be a natural step to follow the previous one (stage 3). Ten countries have fully reached this third stage, whereas twenty-seven have achieved it only partly, having maximum two of the three tools (food-based dietary guidelines, surveillance system on dietary intake and on anthropometry) in place. However, some countries do not exactly follow this pattern and start developing tools without a coordination body in place.

Analysis of policy documents

Approaches of nutrition policy

Nutrition policy is formulated in different policy documents. While some countries have specific food and nutrition action plans, others integrate diet and other risk factors in an overarching strategy on public health or chronic diseases.

The development of the Danish action plan against obesity for instance was the result of the proposed initiatives in the Danish public health strategy Healthy Throughout Life ( 32 ).

In the case of the UK, the White Paper Choosing Health – Making Healthy Choices Easier ( 73 ) served as the overall delivery plan for the action plans Choosing a Better Diet: A Food and Health Action Plan ( 72 ) and Choosing Activity: A Physical Activity Action Plan ( 82 ). In other countries, policy documents address nutrition through an environmental health approach like in Romania and a sustainable development approach like in Austria.

More and more countries have specific strategies on the prevention of obesity. The Czech Republic was the first to set up a national programme for the prevention and treatment of obesity in 2000 and Denmark was the first country in the European Region developing an action plan specifically addressing obesity in 2003, followed by the Spanish Strategy for Nutrition, Physical Activity and Prevention Of Obesity (NAOS) in 2004( 66 ), the Irish strategy Obesity: The Policy Challenges ( 43 ) and the National Programme Against Obesity of Portugal in 2005( 62 ). In 2006, Poland launched the National Prevention Programme Of Overweight, Obesity and Noncommunicable Diseases Through Diet and Physical Activity Improvement 2007–2016 ( 60 ).

Finland, The Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia and the UK developed, in addition to a public health or nutrition plan, a separate document dealing specifically with physical activity in general or specifically with active transport, such as cycling as in the Czech Republic and Germany. A comprehensive analysis of physical activity policies is being conducted within the framework of the European network for the promotion of health-enhancing physical activity (HEPA Europe)( 83 ).

Proposed actions to achieve the goals

The presentation of actions appears to be country-specific and could be related to the political infrastructure or national priority setting. Actions were found to be structured by settings( 45 , 66 , 72 ), policy area( 46 ), priority actions( 36 , 57 ), target groups( 30 ), priority risk factors or diseases( 32 , 56 ) or the three pillars of nutrition, food safety and food security( 28 , 33 , 49 , 65 , 70 , 71 ).

Looking at the types of actions, all analysed documents include actions on information to the consumer, education to the whole population, to schoolchildren and health professionals in particular. Many activities are related to creating a health-promoting environment on the local level, mainly focusing on food supply in schools, hospitals or other public institutions.

Actions addressing the macroenvironment, for instance through the accessibility, affordability, availability, promotion or composition of foods, are found less frequently. Detailed description of those actions, the responsible actors, implementers and the time frame are often missing and could present an obstacle to implementation.

The Swedish Background Material to the Action Plan for Healthy Dietary Habits and Increased Physical Activity is one of the most detailed documents, containing seventy-nine proposals for measures with a comprehensive description of the rationale for the action and responsible actors for each measure, and sometimes the estimated costs are also indicated( 67 ). The Slovenian National Programme of Food and Nutrition Policy lists not only responsible ministries in the list of tasks and activities but also the task performers, which could support the implementation of the actions( 65 ). The Norwegian document A Healthy Diet for Good Health is a good example for setting priorities. The National Council for Nutrition has assigned five high-priority areas and within each of the areas, priority actions are proposed( 58 ).

Evaluating effectiveness

Integrating monitoring and surveillance in nutrition policy is important to assess the effectiveness of health initiatives( 80 , 84 ). Thirty-eight documents from twenty-four countries state that the proposed objectives and activities will be evaluated. In most of the cases this is mentioned only briefly, while some countries developed comprehensive evaluation plans with specific indicators, regular reporting systems and development of databases. The Danish indicator programme for instance includes a wide range of indicators, covering priority areas for risk factors, target groups and settings( 32 ). The task of the Finnish National Nutrition Surveillance System is to collect, interpret, evaluate and distribute data on nutritional status and to assess the need for measures to promote nutrition and health policies. In Spain an obesity observatory was created, regularly quantifying and analysing the prevalence of obesity in the population, especially in infant and young populations( 66 ).

Discussion and conclusions

An unprecedented bout of activities in the domain of nutrition policy is taking place in the European Region( 85 ).

The First Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy of the WHO European Region, in 2000, called for the establishment of food and nutrition action plans on the country level. The 2005 survey revealed that this is realized by most of the countries, as at present forty-six out of fifty-three countries have a final or a draft policy document concerned with nutrition or are in the process of developing such a document.

Despite the progress in food and nutrition policy, most countries are still facing nutrition-related problems. A recent situation analysis indicates that most countries in the European Region have not achieved nutrition and dietary goals. Most of the countries still have excessive fat intake, whereas fruit and vegetable intake is too low and obesity is an increasing problem( 18 ).

The analysis of the available documents revealed that actions addressing the individual with information or education tools are well developed and part of all analysed documents. Current dynamics of the food system (price, availability and accessibility of food) prevent the consumption of a healthy diet, and marketing pressure addresses the demand for food in a completely different direction from what the dietary guidelines indicate.

Although evidence of large-scale interventions at the national level is not widely available, most countries recognized within their strategies that health promotion requires an environment that is supporting healthy lifestyles. The different levels of state involvement can be seen by the wide array of regulatory proposals developed over the past two years. There are some attempts to draft legislation or statutory regulations, for instance on food marketing to children or food labelling.

However, this attempt to create an environment that promotes healthy nutrition still appears very weak in most countries, and only a few documents indicate comprehensive strategies of how to achieve this shift.

The health sector cannot achieve this on its own, and the involvement of different sectors of the government as well as different stakeholders in society is needed( 76 ). In some countries, stakeholders from different sectors are identified and their responsibilities are clearly defined, but only half the countries collaborate with government bodies and the private sector. Creating partnerships could be helpful to clearly define the roles and increase the commitment of all actors. The agricultural sector, the food manufacturing sector and marketing and distribution networks are important actors in food and nutrition policies. National and international policies should create environments to facilitate the achievement of health and nutrition objectives.

Another reason for not reaching nutrition objectives is the quality of implementation. From many countries, information on the implementation and effectiveness of specific interventions is not available yet, as the majority of the strategies were just recently developed. Mechanisms to evaluate and compare the implementation of programmes within and between countries are needed in order to identify good practice, exchange experiences and facilitate the implementation process. However, the survey from 2005 revealed that countries are facing several obstacles to implementation. Countries are struggling mainly with limited political commitment and financial resources. An existing political commitment regarding nutritional issues is evident by the number of available policy documents, but still nine Member States mentioned lack of political commitment as an obstacle for implementation. Strategies to raise political awareness could include cost–benefit calculations, which then could provide a convincing argument to allocate resources.

Policy makers should develop implementation strategies that explicitly take account of financial, managerial and technical aspects of the policy (capacity) and the anticipated resistance and support from all the actors in the subsystem within and outside government, to avoid the gap between policy expectation and reality(Reference Buse 86 ). The analysis of policy documents showed that most of the documents do not include detailed implementation plans. Detailed descriptions of actions, the responsible actors, implementers and the time frame are often missing.

The methodology of the present paper calls for some caution when interpreting results. The analysis is limited to national policy documents and strongly relies on objective information provided by national nutrition counterparts of health ministries. The applied tool for analysis presents a novel approach, which has not been validated yet. The final step of implementing the recommendations stated in policy documents was not considered for the present analysis. Validated and standardized policy tools are needed to systematically analyse and compare policy implementation, as well as common elements, to identify good practice.

The present paper provides a basis to identifying stages of policy development. The different stages have important implications for setting priorities. Countries that have not yet achieved the first stage might give priority to political and institutional development, whereas countries having reached that stage have the opportunity to develop policy tools for the implementation of their policies. The Second WHO European Action Plan for Food and Nutrition provides a plan for implementation, indicating the different entry points related to the stage of policy development. It further proposes a set of specific actions, aiming to create an environment that encourages the responsibility of individuals and making healthy lifestyles the default.

Overall, the Region is doing well in the development of nutrition policies. However, there needs to be stronger support in the implementation and evaluation of those policies and a shift towards stronger environmental approaches.

Acknowledgements

F.B. designed the policy analysis model. U.T. collected and analysed the information from countries. The authors wish to thank Aileen Roberts, Rebecca Goldsmith and Dorit Nitzan Kaluski for conducting and evaluating the survey in 2003. They extend sincere thanks to country counterparts for submitting information on food and nutrition policies as well as their policy documents. No funding has been received for the preparation of this paper. There is no conflict of interest to be disclosed.