Diet-related noncommunicable diseases (NCD) and obesity impose a significant health and economic burden in Australia and globally(Reference Naghavi, Abajobir and Abbafati1,Reference Crosland, Ananthapavan and Davison2) . In 2018, 1 in 2 Australians were affected by at least one NCD, including CVD, diabetes and cancer(3). Rates of overweight and obesity have steadily increased over the past three decades, with most recent estimates indicating 67 % of Australian adults (aged ≥18 years) and 24·9 % of children (aged 5–17 years) are overweight or obese(4).

Globally, the rise in prevalence of NCD and obesity has been attributed to major shifts in food systems, including the proliferation of obesogenic environments characterised by the increased availability, marketing intensity and consumption of cheap ultra-processed foods(Reference Swinburn and Egger5,Reference Monteiro, Moubarac and Cannon6) . To attenuate these systemic drivers of obesity and NCD, a comprehensive national nutrition policy containing a broad package of synergistic policy actions that engages multiple sectors of government (e.g., health, agriculture and trade) is required(Reference Sacks, Swinburn and Lawrence7-9). Although not a guarantee for implementation, institutions such as the WHO have recommended that countries adopt this whole-of-government approach to policy in order to meet the WHO’s targets on diet-related NCD and Sustainable Development Goal Target 2.2 on ending all forms of malnutrition by 2030(9-11). Despite this however, global uptake has been slowly and largely focused on discrete and disjointed policy actions that have had little effect on population health outcomes(12).

Australia is a liberal-democratic federation with a governmental structure that is comprised of federal, state/territory and local level administrations, with allegiances to the United Kingdom’s Commonwealth of Nations. The federal government is elected by popular vote for a 3-year term through a bicameral system of Parliament, consisting of the House of Representatives (Lower House) and the Senate of Australia (Upper House). The Executive branch, often referred to as the ‘Australian Commonwealth government’, consists of the Prime Minster and Cabinet and is determined by a political party or parties holding the majority of seats within the House of Representatives. This branch is responsible for developing and implementing federal policy, including nutrition policy, through the various bureaucratic departments and agencies, collectively known as the Australian Public Service(Reference Woodward, Parkin and Summers13).

In 1992, Australia launched a comprehensive and intersectoral national nutrition policy that not only sought the promotion of healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet-related NCD but also included considerations for environmental sustainability and social justice(14). Recently, leading public health groups have repeatedly called for the development of a new comprehensive national nutrition policy, similar to that launched in 1992(15,16) . In 2011, the Australian Commonwealth government commissioned a review of Australian food labelling laws and regulations, resulting in the ‘Labelling Logic’ report which made a number of recommendations including that the federal government initiates the ‘development of a comprehensive Nutrition Policy’(Reference Blewett, Goddard and Pettigrew17). The recommendation has yet to be fully adopted. However, in the absence of a comprehensive nutrition policy, initiatives such as the ‘Healthy Food Partnership’ (the Partnership) have seemingly gained priority amongst health policy-makers in recent years(18). Established in November 2015, this public–private partnership (PPP) involves a collaboration between representatives from government, health and consumer organisations, and the food industry. The Partnership focuses primarily on voluntary policy actions that target three primary objectives: consumer education; portion and serving size standardisation; and food reformulation, complemented by the Health Star Rating (HSR) front-of-pack labelling system(19).

In recent decades, PPP have gained significant traction globally as governance structures for responding to a wide range of social and environmental challenges, including nutrition(Reference Hawkes and Buse20,Reference Kraak, Swinburn and Lawrence21) . However, nutrition-related PPP have been widely criticised for their inability to dissociate inherent food industry conflicts of interest from their intended public health objectives(Reference Ludwig and Nestle22-Reference Kraak, Harrigan and Lawrence24). Moreover, recent research has illustrated the disproportionate power and influence of the food industry over Australian nutrition policy decision-making, relative to that of nutrition and public health professionals(Reference Cullerton, Donnet and Lee25). This, coupled with the significant barriers posed by political actors (e.g., politicians) and the tendency for government departments to limit the scope of decision-making to noncontroversial policy issues, has resulted in little political appetite for the crucial regulatory components (e.g., taxes on unhealthy food and drinks) of a national nutrition policy that are required for promoting a healthier food system(Reference Baker, Gill and Friel26-Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender28).

Despite these developments, few studies have investigated how the scope of Australian federal nutrition policy actions has changed over time to the currently preferred PPP-centred approach(Reference Swinburn and Wood29-31). It remains unclear whether nutrition policies in recent years have reflected the comprehensive approach required to drive systemic changes and effectively improve nutrition outcomes(Reference Sacks, Swinburn and Lawrence7-9). Furthermore, factors that are likely to have led to such changes in policy direction remain under-explored.

In addressing these research gaps, the current study aims to critically analyse trends in the scope of Australian federal nutrition policy actions during the period 2007–2018. The year 2007 corresponds with the election of a Commonwealth Labor government and a commitment to a renewed preventative policy health agenda, including nutrition policy, for Australia(Reference Roxon32,Reference Roxon33) . It adopts an Australian case study design with two objectives: first, to describe the changes in the scope of nutrition policy actions benchmarked against an international best-practice policy framework; second, to investigate how and why the scope of nutrition policy actions changed over time, by examining the decision-making processes that led to the establishment of the Partnership.

Methods

The current study used a single, case study design, chosen for its suitability for investigating a complex multi-variant phenomenon(Reference Yin34). The investigation proceeded in two stages. First, Australian Commonwealth government policy documents were organised along a chronological timeline of key policy developments and then analysed against a best-practice nutrition policy framework to determine the content and scope of policy actions. Second, members of the Partnership’s Executive Committee and Reformulation Working Group (RWG) were recruited to be interviewed as key informants. Executive Committee members were selected from the list of organisations involved in the Partnership in order to explain how the scope of nutrition policy in Australia may have narrowed over the past decade. Many of these organisations were similarly involved with the Food and Health Dialogue(35) – the Partnership’s predecessor – suggesting that these members have been involved in nutrition policy-making in Australia for some time. Food reformulation is a key policy area within the Partnership, and thus, RWG members were recruited based on their potential to provide insights into its internal and operational decision-making processes.

Trends in the scope of nutrition policy and actions

Document collection

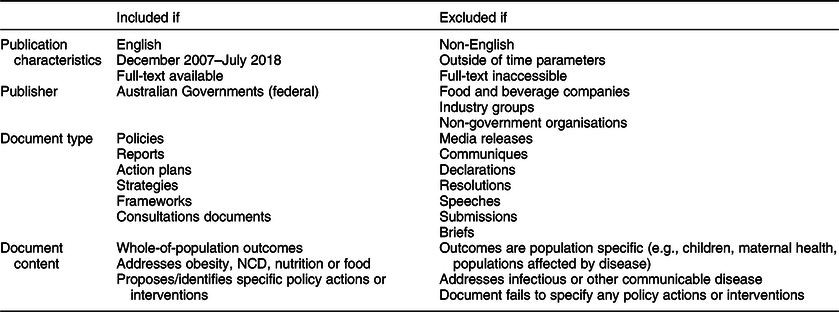

Policy documents published by Australian Commonwealth governments between December 2007 and July 2018 were collected. Policy documents published by state/territory or local level governments were not included as this paper primarily focused on federal level policy actions. A full list of document inclusion and exclusion criteria was discussed and agreed to by all authors and is presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria for policy document analysis

A combined systematic and snowball search strategy, involving three phases, was used to source relevant policy documents. Phase one involved searching the grey literature using Google Advanced. Key search terms included ‘health’, ‘noncommunicable’, ‘chronic’, ‘nutrition’, ‘food’, ‘preventative’, ‘plan’, ‘framework’ and ‘strategy’. Domain parameters were limited to websites of the Australian Department of Health, Freedom of Information Disclosure Log, state and territory health departments and national library or internet archives. Phase two involved an on-site search, using the terms described above, to identify potentially missed publications. Phase three involved the examination of the reference lists of any retrieved documents.

To give greater context, documents were organised chronologically into a timeline of Australian nutrition policy developments. Publicly recorded key events relating to the identified policy documents were also searched and added as timeline items. Timeline items included media releases, communiques, news articles, reports, speeches, Parliamentary Hansards and any other published materials that were relevant to Australian nutrition policy.

Document analysis

To compare the scope of policy actions contained within each document, the current study enlisted the World Cancer Research Fund International’s NOURISHING framework(Reference Hawkes, Jewell and Allen36). The NOURISHING framework formalises the comprehensive package of nutrition policy actions proposed by the WHO Global Action Plan(9) by outlining ten evidence-based policy areas by which policy actions can be developed and implemented to address the nutrition challenges faced within a regional, national or local context. A coding-tree was adapted from NOURISHING and organised in accordance to the frameworks, domains, policy areas and sub-policy areas. Documents were coded in line with well-established document analysis techniques(Reference Bowen37) using QSR NVivo (version 11) qualitative analysis software.

Decision-making processes that led to the Partnership’s establishment

Data collection

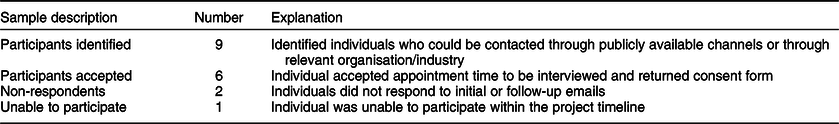

Five key-informant interviews were conducted, with a sixth responding by email (Table 2). The participants were representatives of the government (n 1), private sector (n 3) and non-government sector (n 2). Participants were identified and recruited using a purposive sampling strategy, which targeted individuals from the Partnership’s Executive Committee and RWG. Relevant Executive Committee members were identified by consulting the documents used to develop the chronological timeline of Australia’s nutrition policies and cross-referencing likely members with committee organisations.

Table 2 Number of key-informant participants

Contact was established using publicly sourced email addresses or through a participants’ relevant organisation and requesting a direct contact. After initial contact and expression of intent, participants were sent a formal letter of invitation, language statement and consent form containing further details of the study.

Single, semi-structured and audio-recorded interviews were conducted over an agreed 50–60 min telephone call between July and August 2018. An interview guide was developed, containing primarily open-ended questions, which ensured a consistent line of enquiry, but also allowed for relevant information to be probed(Reference Draper and Swift38,Reference Patton39) . Participants were profiled for past involvement with nutrition policy initiatives and had their interview subsequently tailored to prioritise the most relevant questions. All interview transcripts were member checked and de-identified. Participants are referred to by number only (e.g., Informant 5).

Data analysis

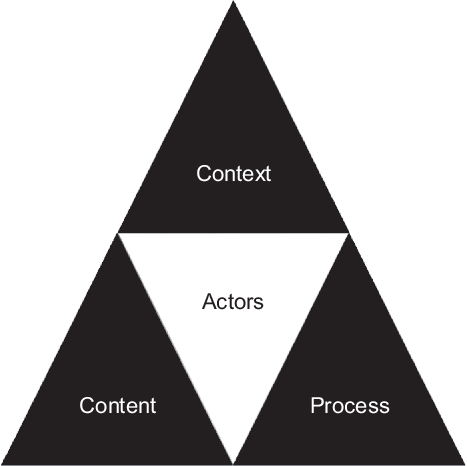

Transcripts underwent a multiphase thematic analysis described by Saldaña(Reference Saldaña40) and were theoretically guided by the health policy triangle framework (Fig. 1)(Reference Walt and Gilson41). The health policy triangle provided an analytical framework that was able to capture the complex interactions between actors, context, policy content and processes during policy-making, and in this case, the factors that led to the Partnership’s establishment and focal policy actions(Reference Walt, Shiffman and Schneider42). Transcripts were coded using QSR NVivo (version 11) software. Inter-coder reliability was tested by each author coding one transcript and discussing any points of contention until consensus was reached.

Fig. 1 Health policy triangle

Results

Trends in the scope of nutrition policy and actions

In December 2007, the Australian Labor Party (ALP) was elected to govern after 11 years of a Liberal and National coalition government (the Coalition). The election of the ALP government meant a comparatively rejuvenated commitment to a preventative health policy agenda. This was evident in Nicola Roxon’s designation of obesity prevention as a ‘National Health Priority Area’ as the newly appointed Minister for Health and Ageing(Reference Roxon32,Reference Roxon33) . Over the ensuing decade, Australia’s nutrition policy priorities have received fluctuating levels of commitment from both major political parties, the ALP and Coalition governments, as outlined in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Timeline of Australia’s nutrition policy agenda from December 2007 to July 2018. ANPHA, Australian National Preventative Health Agency; COAG, Council of Australian Governments; DOH, Department of Health; HFP, Healthy Food Partnership; HSR, Health Star Rating; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NPAPH, National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health

This period was characterised by a ‘start-stop’ sequence of events in which nutrition challenges were recognised, a nutrition policy response was formulated and occasionally implemented, but then momentum was stopped by a change in government, resulting in the decision-making process restarting all over again. For instance, nutrition underpinned much of the ALP governments’ preventative health policy architecture between 2008 and 2013. This architecture saw a number of policy measures including the establishment of the National Preventative Health Taskforce(43), National Partnership Agreement on Preventative Health(44) and Australian National Preventive Health Agency(45). Furthermore, the ALP initiated the Food and Health Dialogue(35) – the precursor to the Partnership – and had allocated funding for a scoping study and evaluation of evidence to inform the development of a comprehensive national nutrition policy(46,Reference Lee, Baker and Stanton47) .

However, with the election of the Coalition government in late 2013, much of the previous government’s preventative health architecture was dismantled and many of nutrition policy initiatives de-funded(48). Following this, a multi-stakeholder consultation workshop was held in March 2014 to discuss the translation of the scoping study into a nutrition policy (confirmed by personal communications with Rodger Watson, ThinkPlace Sydney Studio Lead, 2018). However, no further actions eventuated from this workshop and progress towards the comprehensive national nutrition policy effectively ceased. It was not until the 8 November 2015 that the Australian Commonwealth government released a media statement announcing the establishment of the Partnership(18).

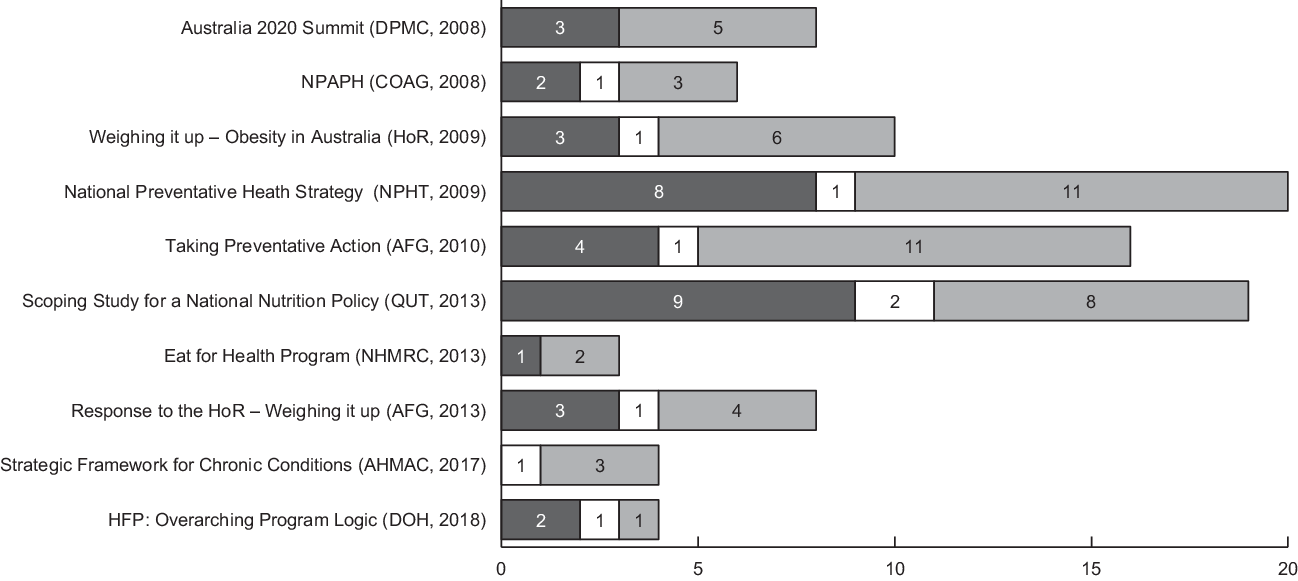

Ten documents published by Australian Commonwealth governments were retrieved. Across all documents, ninety-eight policy actions were identified and categorised using the NOURISHING framework (Fig. 3). There is a noticeable skew towards behavioural change communication policy actions, which comprised 55·1 % of all policy actions, followed by 35·7 % in food environment and 9·2 % in food system. The full distribution of policy actions across all documents can be viewed in online Supplementary Material 1.

Fig. 3 Scope of Australian national nutrition policy actions published between 2007 and 2018 categorised against NOURISHING framework. AFG, Australian Federal Government; AHMAC, Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council; COAG, Council of Australian Governments; DOH, Department of Health; DPMC, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; HFP, Healthy Food Partnership; HoR, House of Representatives; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NPAPH, National Partnership Agreement for Preventive Health; NPHT, National Preventative Health Taskforce; QUT, Queensland University of Technology. *Document titles shortened. ![]() , food environment;

, food environment; ![]() , food system;

, food system; ![]() , behavioural change communication

, behavioural change communication

Document analysis indicates that the scope of nutrition policy and actions adopted in Australia since December 2007 has narrowed to four, mostly discrete, policy actions contained within the Partnership. Commonwealth documents published during the ALP governments (2007–2013) proposed a greater number and variety of policy actions than those published during the Coalition governments (2013–2018). Federal government documents such as the National Preventative Health Strategy (n 20) and scoping study for a National Nutrition Policy (n 19) documents contained the greatest number of policy actions. The Partnership Overarching Program Logic (n 4) and Reformulation Program: Public consultation (n 3) documents contained the least.

How and why was the Partnership established?

Presented below are the findings from a thematic analysis of key-informant interviews which sought to understand why the scope of Australian nutrition policy and actions has narrowed over time.

Pragmatism and compromise

There was an emphasis amongst stakeholders to be pragmatic and make compromise when participating within the Partnership and engaging with other stakeholders, particularly food industry representatives. This approach heavily influenced the outcomes of decision-making processes, at both the Executive Committee and working group levels of the Partnership. Pragmatism was evident in some informants’ perspectives regarding the need to engage the food industry to ensure policy success. For example, one informant spoke of the necessity for government to harness the resources and expertise of industry to ensure that nutrition policies could be effectively implemented at scale.

Industry has the ability to innovate and renovate at a speed that government cannot and government doesn’t have the resources to do that… you need to engage the food industry, there’s just no other way. (Informant 1)

More generally, when reflecting on their involvement with PPP, one informant spoke of their experience when participating in both the previous Food and Health Dialogue (the Dialogue) and Partnership, and how pragmatism and compromise informed a large part of their approach.

…all the things that I’ve achieved have all been about making compromise and finding the art of the possible. Have we compromised too much? That’s an open debate … in the end, it’s really a judgement call. (Informant 3)

The same informant explained further that this approach of compromise served a larger strategic goal to foster better relations between their organisation and the government. Participation in both PPP meant greater proximity to policy-makers and opportunities for advocacy.

Attitudes of pragmatism and compromise were also evident at the working group level. For example, RWG informants described reformulation as a realistic policy approach to improve the consumption of core food groups without having to drastically change consumer behaviour.

The way I look at reformulation is in a pragmatic, real-world sense, in that I look at peoples diets and how hard it is to change those through policy measures. And reformulation is a tool that doesn’t rely on any change in behaviour… (Informant 4)

More specifically, most RWG informants suggested that their limited selection of three reformulation nutrient targets (i.e., total sugar, saturated fat and Na) stemmed from a compromise between considerations of feasibility, evidence gaps and food industry receptiveness. For instance, two participants stated:

…there’s a huge cost of goods implications for introducing more core food ingredients in products … that is why you don’t get reformulation programs targeting fruit and vegetables [for example] at a government level. (Informant 4)

…it was considered too difficult to set [other] targets … we don’t know how much wholegrains, for example, is in different products. We don’t have a baseline to then [say] “ok we want to increase the wholegrain content of bread by X percent” … there’s a lot of data gaps there… (Informant 5)

Actors: relationships and lobbying actions

Actors played an important role in influencing the establishment of the Partnership through lobbying actions and leveraging relationships, all of which contributed to the narrow scope of policy actions. Most informants could not comment on the activities of individual or organisational actors. However, one informant provided key insights on how the lobbying efforts of the food industry were critical to the recruitment of individuals who had a tendency towards pragmatism and compromise:

[Our experience was] we could disagree on quite fundamental matters, but… work on the areas that we could achieve things together… [food industry representative] said to me “if I could talk [the government] into taking you onto the Food and Health Dialogue, would you be prepared to use the same approach?” I said “yes” and so that’s really how I wound up on the Food and Health Dialogue, ironically, with the [food industry] luring me onto it. (Informant 3)

Lobbying actions were also crucial to establishing nutrition policy priorities for Prime Minister Abbott’s Coalition government, which had dismantled much of the previous ALP government’s preventative health policies shortly after being elected in September 2013. The informant explained that lobbying was targeted towards key individuals within the Coalition government to re-establish the Dialogue or an equivalent. They further explained that there were a number of public health and consumer organisations actively involved in lobbying the newly elected Coalition government in order to re-establish nutrition as a policy priority. However, the establishment of the Partnership itself appears to have been a product of negotiations between a small number of individuals, as opposed to a broader consultation, indicating that the agenda-setting power lies with a select few individuals.

… the strongest [lobbying] that I was aware of… came from the discussions between [two other individuals] and myself. (Informant 3)

Furthermore, strong inter-organisational relationships between the health advocacy groups, in both the Dialogue and the Partnership, were important during conflicts with other stakeholder groups, particularly the food industry representatives. Collective actions between these groups are likely to have contributed to the overall scope of the Partnership.

…there was certainly a number of times that [other health advocacy groups and] ourselves talked about “is it time to resign?”. Because if we were going to resign, we would do it very publicly… and I think industry and other members sensed it and compromised under those circumstances. (Informant 3)

Political context

The establishment of the Partnership also appears to have been enabled by the Australian political context, namely ideological resistance towards regulation and the alignment of lobbying actions with key political events. Responses from two informants indicate that the ‘voluntary’ nature of the Partnership was driven by ideological preferences for minimal government regulation and the expanded role of the private sector in public policy and governance. Additionally, it was noted that the Partnership’s establishment was not informed by a review of international evidence on best-practice approaches to nutrition policies, further indicating the role of political values within policy decision-making processes. One informant stated, for example:

The coalition government’s preferred approach is to collaborate rather than regulate … There was not a specific literature review process [of voluntary versus mandatory initiatives]. A policy decision was made by the then Minister Nash and the Partnership Executive Committee that initiatives under the Partnership will be voluntary. (Informant 6)

Another participant commented:

…I believe we were never going to get one of those [mandatory nutrition initiatives] in Australia because we have such a strong anti-regulation drive… from both major [political] parties. So in the end, politics is the art of the possible. (Informant 3)

Most participants were unable to comment on the immediate events preceding the Partnership. However, one informant suggested that its establishment was a result of the political controversy surrounding the shutdown of the HSR system website in February 2014, under the directive of the then Minister Nash, just hours after it launched. A number of media articles had reported that Minister Nash’s Chief of Staff was married to the owner of a food industry lobbying group and had seemingly requested the website be taken down(Reference Jabour and Chan49,Reference Harrison50) . The informant explained that a number of public health groups immediately responded by coordinating a media effort with the goal of re-launching the HSR website. These actions provided certain health advocates with the opportunity to re-assert nutrition policy back onto the national agenda.

…you have to see this in the context also of the HSR because I was working with others on the media effort regarding the HSR website coming down and was subsequently involved in a series of discussions with the federal minister… which led to the HSR being adopted [by the Coalition government] and the establishment of the Healthy Food Partnership. (Informant 3)

Discussion

Our findings indicate that Australian policy-makers were working towards developing a comprehensive national nutrition policy in 2013, but this process suddenly stopped from 2014 onwards. When compared with past Australian nutrition policy documents that were analysed against a best-practice policy framework, it was found that the Partnership is a relatively discrete policy approach with its scope of actions too narrow to address many of the systemic drivers of diet-related NCD. For instance, there were no actions that involved a contribution from government sectors beyond Commonwealth and state/territory health departments or that addressed the socio-ecological determinants of nutritional health. Interviews with Partnership key informants provided insights into how and why this narrowing of policy actions occurred. Thematic analysis of interview transcripts revealed: pragmatism and compromise; actor relationships and lobbying actions; and the political context as explanations for the establishment of the Partnership in its narrow scope.

Critically, our analysis shows that Australia’s current nutrition policy approach, the Partnership, is narrow in scope, both in terms of the number and variety of policy actions. We identified the Partnership to contain four specific nutrition policy actions. These findings indicate that the scope of the Partnership’s actions falls short of system-wide recommendations to effectively reduce obesity and diet-related NCD(Reference Sacks, Swinburn and Lawrence7,Reference Sacks, Swinburn and Lawrence8) as well as those outlined within the 2013 nutrition policy scoping study(Reference Lee, Baker and Stanton47). Furthermore, the narrow scope of the Partnership is inconsistent with the most recent Lancet Commission for obesity, which recommends a greater commitment to broader ecological approaches in policy and regulation in order to drive meaningful change away from unhealthy food systems(Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender28).

Explanations for the narrowing of the nutrition policy scope can be found in the key informants highlighting that the establishment of the Partnership was driven by views of pragmatism and compromise, the influence of key actors and the realities of the political context during decision-making processes. Calls for academics to engage with the nutrition policy-making process in a less rigid and more pragmatic manner are not new(Reference Winkler51). More specifically, previous works have discussed the need for a pragmatic approach for how academics and health advocates use scientific evidence to bridge the ‘evidence-policy gap’(Reference Ansell and Geyer52,Reference Cairney and Oliver53) . The key question that follows from this situation is ‘what level of compromise regarding the nature and scope of nutrition policy should nutrition advocates accept as pragmatically necessary for achieving national nutrition policy?’

In the case of the Partnership, pragmatism and compromise between government, NGO and food industry stakeholders, may have come at the cost of stronger nutrition policy. Recent research indicates that the involvement of food industry stakeholders within PPP has meant the proliferation of largely ineffective self-regulatory actions over mandatory regulation(Reference Challies54,Reference Clapp and Scrinis55) . These PPP have often resulted in the tendency to narrow down policy responses to options that are more palatable and considered ‘safe’ by food industry stakeholder(Reference Clapp and Scrinis55,Reference Baker, Machado and Santos56) . In a more specific example, corporate political activity research indicates that voluntary reformulation – a key component of the Partnership – serves as a policy substitution mechanism that forms part of the broader food industry strategy to pre-empt regulatory action(Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Allender57,Reference Scott, Hawkins and Knai58) . This, coupled with the arguably little progress made by the Dialogue(Reference Elliott, Trevena and Sacks59-Reference Jones, Magnusson and Swinburn61) and the growing evidence that mandatory reformulation initiatives substantially out-perform voluntary approaches(Reference Downs, Bloem and Zheng62-Reference Hyseni, Elliot-Green and Lloyd-Williams64), calls into question the voluntary nature of the Partnership, as well as the subsequent utility of the pragmatic approach to decision-making during its establishment.

Our findings are broadly consistent with those reported from previous research by the Healthy Food Environment Policy Index project(30,31) , which aimed to track the implementation status of nutrition policy actions across federal, state and territory jurisdictions from 2016 onwards. Despite having broadly similar aims, the two analyses are not entirely comparable in two particular respects. Firstly, our analysis utilises a more critical approach towards Australian policy actions (e.g., voluntary reformulation within the Partnership) and refrains from adopting the Commonwealth government’s own parameters in determining their appropriateness and utility for achieving public health outcomes. Secondly, Healthy Food Environment Policy Index focused largely on tracking food environment type policy actions, whereas our analysis utilised the NOURISHING framework to broaden the lens and encapsulate behaviour change communication and food system type policy actions. As such, our findings were able to demonstrate that on a ‘macro’ level, federal policy actions in Australia have been relatively skewed towards behavioural change communication compared with food environment and food system type actions. Broadening our lens has meant that our analysis did not necessarily reflect the same degree of sensitivity in tracking individual policy actions as Healthy Food Environment Policy Index. Nevertheless, combined with key-informant interviews, our findings provide additional insights into why a comprehensive national nutrition policy in Australia is yet to be established.

These findings are the first to demonstrate a trend of a narrowing policy scope and actions in Australia over the past decade. The current study is the first investigation to provide detailed key informant insights into factors that help explain the establishment of the Partnership. However, the trend analysis cannot be used to assess the degree to which those policy actions have been implemented, nor how successful they are within their respective contexts. Furthermore, some documents were specifically single interventions, whereas others were more broadly focused, which presents a limitation when comparing the number of policy actions between them. Moreover, this paper focuses on the federal level does not consider nutrition policy actions that have been developed and implemented at the state, territory and local government levels. It is important to acknowledge the myriad of nutrition policy work being conducted by these jurisdictions, as well as their likely involvement in the development and implementation of a future national nutrition policy. However, a detailed analysis of state, territory and local government level policy actions was beyond the scope of this paper. Lastly, all the key informants were involved with the Partnership in various capacities and thus were potentially subject to bias in viewing the Partnership’s activities in favourable terms.

Conclusions

A comprehensive national nutrition policy containing a broad package of synergistic policy actions that engages all sectors of government and targets the food system as a whole is needed to help promote public health nutrition. The current study has found that the scope of nutrition policy actions in Australia has narrowed over the past decade to a relatively small number of discrete policy actions. This narrowing of the nutrition policy agenda can largely be attributed to attitudes among the involved stakeholders of pragmatism and compromise, the influence of actor relationships and lobbying, and the constraints and opportunities presented by the political context during decision-making processes. In this political dynamic, nutrition policy advocates in Australia and around the world are faced with the difficult dilemma: should (and if so, how) a balance be sought between advocating for aspirational, but possibly unrealistic goals, and accepting the limited but likely outcomes during policy-making processes? The announcement of the new National Preventive Health Strategy in June 2019(65) and consultation for a National Obesity Strategy in November 2019(66) presents public health policy-makers with an opportunity to broaden the scope of policy actions beyond that of discrete measures such as the Partnership and elevate political commitment towards a comprehensive national nutrition policy. We believe these present findings will provide relevant insights for public health nutrition stakeholders involved in the decision-making and consultation processes for these new policy developments.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to extend their gratitude to the Australian Commonwealth Department of Health for providing advice, background and commentary, as well as all of the Healthy Food Partnership members who volunteered their time to participate in this research. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: B.I. declares no conflicts of interest. M.L. declares that at the time of this research his spouse was a member of the Reformulation Working Group. This individual was excluded as a potential key informant. P.B. declares no conflicts of interest. Authorship: M.L. conceived the study, B.I. and P.B. contributed to the study design. B.I. collected and analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the paper. M.L. and P.B. provided guidance throughout the study’s conduct and contributed by reviewing, editing and approving all drafts and final version of the paper. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Deakin University Human Ethics Advisory Group. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020003389