More than half of Portuguese adults are overweight, creating a significant public health crisis due to the concomitant increased risks to physical and psychological health. According to the latest statistics, in 2012, 40 % of the Portuguese adult population was overweight and almost 20 % was obese( Reference Sardinha, Santos and Silva 1 ), which represents a significant economic cost (about 3·5 % of total health-care expenditures per year( Reference Pereira and Mateus 2 )) and a great loss of quality of life as well as earlier mortality.

Dietitians are at the forefront of providing nutrition management. As reported in previous studies, weight management forms a substantial component of dietitians’ workload, being the problem they encounter most often in their clinical practice. They rank themselves as the most prepared, trained and effective providers of weight-management advice, see this area as an important part of their job and are willing to engage lifestyle interventions( Reference Campbell and Crawford 3 – Reference Endevelt and Gesser-Edelsburg 5 ). However, as happens among other health-care professionals, their practices do not seem to be immune to prejudicial attitudes and stereotypes towards obese people. Despite the widespread literature, there is no consensus regarding dietitians’ attitudes about obesity and obese patients, with several studies reporting positive( Reference McArthur 6 , Reference Harvey, Summerbell and Kirk 7 ), neutral( Reference Harvey, Summerbell and Kirk 7 , Reference McArthur and Ross 8 ) and negative attitudes( Reference Campbell and Crawford 3 , Reference Oberrieder 9 ), not only among registered dietitians but also among trainee students( Reference Swift, Hanlon and Puhl 10 – Reference Puhl, Wharton and Heuer 12 ). Still, little is known about the way those attitudes influence dietitians’ practices, representing a gap in terms of qualitative research exploring this topic in depth( Reference Budd, Mariotti and Graff 13 ). In Portugal, nothing is known about dietitians’ beliefs, attitudes, role perception and practices regarding obesity treatment and, at present, there are no national obesity practice guidelines. So, the present study is the first to access the beliefs, attitudes and practices of Portuguese dietitians using a qualitative approach to systematically assess and understand how they perceive this epidemic and these patients, how they perceive their role in the management of this disease and what they are doing about it.

In addition, there is currently a lack of literature comparing practices in public primary-care and private settings. Much research including participants from both settings rarely explores differences between them( Reference Barr, Yarker and Levy-Milne 4 , Reference Chapman, Sellaeg and Levy-milne 14 , Reference Almajwal, Williams and Batterham 15 ), and the few studies accessing practices in the private setting reveal more positive outcomes and perceptions and differences in dietitians’ approaches and practices( Reference Zinn, Schofield and Hopkins 16 – Reference Brown, Mitchell and Williams 19 ). In Portugal, most dietitians perform private self-funded practice and clients usually have to pay for the consultation entirely since this service is not usually covered by health insurance. On the contrary, nutrition consultations in public primary-care services are entirely free since they are delivered through government-funded public institutions, but access to this service is difficult due to the lack of human resources and is determined by general practitioners’ referrals. These contrasts emphasize the need to investigate differences among these settings, what is behind them and what implications they bring to intervention and weight-loss outcomes.

The present paper aims to fill some of the described gaps by exploring (i) Portuguese dietitians’ beliefs and attitudes about obesity and their implications for practice and (ii) possible differences in dietitians’ beliefs and practices between the public primary-care setting and private setting. To explore these issues, we conducted a qualitative study guided by two related questions:

-

1. What are Portuguese dietitians’ beliefs and attitudes about obesity and obese people and how are they handling obesity treatment?

-

2. How do the dietitians’ beliefs, practices and role perception change according to their work setting?

Methods

Approach

To address the identified gaps in the current literature relating to the lack of qualitative studies about the perceptions of health-care professionals concerning obesity( Reference Budd, Mariotti and Graff 13 ), we undertook a thematic analysis following the guidelines developed by Braun and Clarke( Reference Braun and Clarke 20 ). According to these authors’ terminology, we adopted an essentialist paradigm as a research theoretical framework since we were interested in reporting experiences, meanings and the reality of participants, with some level of interpretation. Thematic analysis as a qualitative method, used for ‘identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data’( Reference Braun and Clarke 20 ), provided a systematically and deeper understanding of dietitians’ views and meanings regarding obesity management by going beyond the data achieved through quantitative surveys. Indeed, while statistical information is needed and important, it does not capture descriptions and meanings of the human experiences. In the present study, qualitative research methods appeared a better fitting method since we were trying to get access to an unexplored theme in the literature and we wanted a complex, context-dependent and detailed understanding of the dietitians’ meanings and experiences regarding obesity management, that could generate in-depth evidence to improve practices( Reference Taylor and Francis 21 , Reference Creswell 22 ).

The study was approved by the Health Committee of Ethics of the North of Portugal and by the Ethics Board of the University of Porto.

Participants and data collection

We purposively sampled dietitians working within urban and rural public primary health-care institutions and private health clinics with nutrition consultation service, both in the north of Portugal (restricted to this area for reasons of convenience). For the purposes of the present study, a private practice dietitian refers to a dietitian who is employed in the private sector or self-employed to provide dietetic services outside the public health system. Dietitians were invited to participate by telephone and/or after the approval of the heads of the health-care institutions. After the first contacts, a snowball sampling was also undertaken to get access to other institutions and professionals. To be included in the sample, dietitians had to be registered, have a degree in nutrition, work in the public primary health-care setting and/or private health clinics, and have at least two years of experience.

Semi-structured face-to-face interviews of 55–90 min were conducted between January 2012 and June 2014. All interviews were conducted by the first author at dietitians’ workplace and at a time convenient to the participant. Written consent to participate in the study and to audio-record the interview was obtained. Handwritten notes were made at the end of each interview to record emergent thoughts and ideas. After a review of the literature, the research team developed a provisional interview guide schedule with eight open questions concerning general knowledge about obesity, feelings towards obese patients and practice approaches. Adaptations and questions were added to the script according to the interview setting, as shown in Table 1. Probing questions were also used to clarify information and gain additional data. Data collection and analysis were conducted concurrently. We employed an iterative approach, using data from earlier interviews to inform later questioning and to refine the interview schedule. Recruitment of participants discontinued upon saturation, i.e. when no new insights were arising from the data, which occurred around the fourteenth interview (public setting n 8; private setting n 6). However, to increase study quality and trustworthiness, three extra interviews were conducted (public setting n 2; private setting n 1). Participants also completed a short survey in the end of each interview eliciting demographic data.

Table 1 Interview schedule developed for semi-structured interviews with Portuguese registered dietitians working in public primary-care (n 10) and private settings (n 7), January 2012–June 2014

Data analysis

The qualitative software QSR NVivo 10 was used to manage, code and analyse the data. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and a nominated code (RD (registered dietitian) plus a number) was given to each participant to preserve confidentiality and anonymity. We conducted an inductive thematic analysis( Reference Braun and Clarke 20 ), meaning that we adopted a data-driven approach rather than from a priori theory, whereby significant topics, recurring terms, statements or ideas, interesting features or patterns were highlighted. A constant comparative method was adopted throughout. The first four interviews were open-coded by the first author to develop an initial coding frame that was discussed afterwards with the other two authors, who also read and developed a set of themes. Discrepancies were recorded and discussed until mutual agreement was reached (≥85 % agreement). An iterative approach was taken in which the initial coding frame developed was used as a guide to systematically code and review the other interview transcripts. As analysis of transcripts progressed, the authors meet frequently (every fourth interview) and the coding frame was discussed and revised in response to new data until the most commonly cited concepts were identified and a logical, coherent, clear and consistent pattern emerged. Reflexive diaries were written during this process. Thematic maps (tree maps) were modelled to visually represent the relationships between key themes and sub-themes and consequently interpreted to comprise the findings. Themes saturation was achieved by the fourteenth interview. Frequent meetings and discussions between the authors ensured thorough coding and agreement in the development of framework themes and sub-themes.

Results

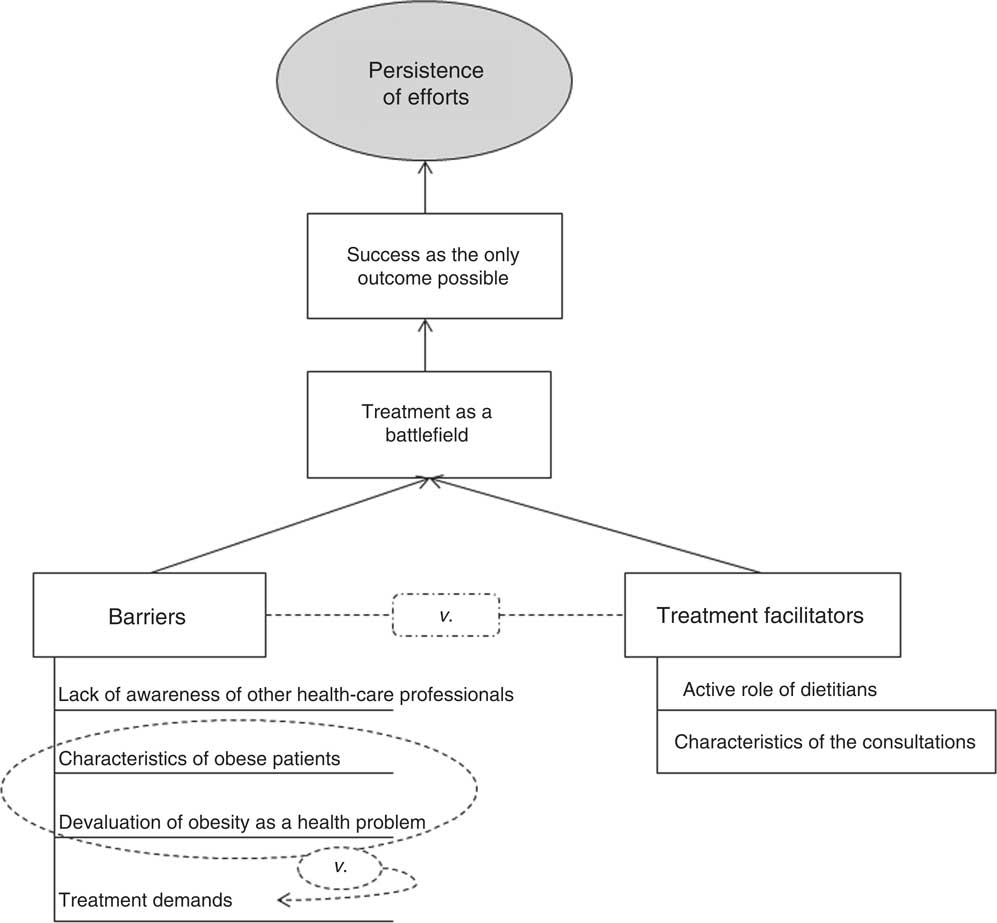

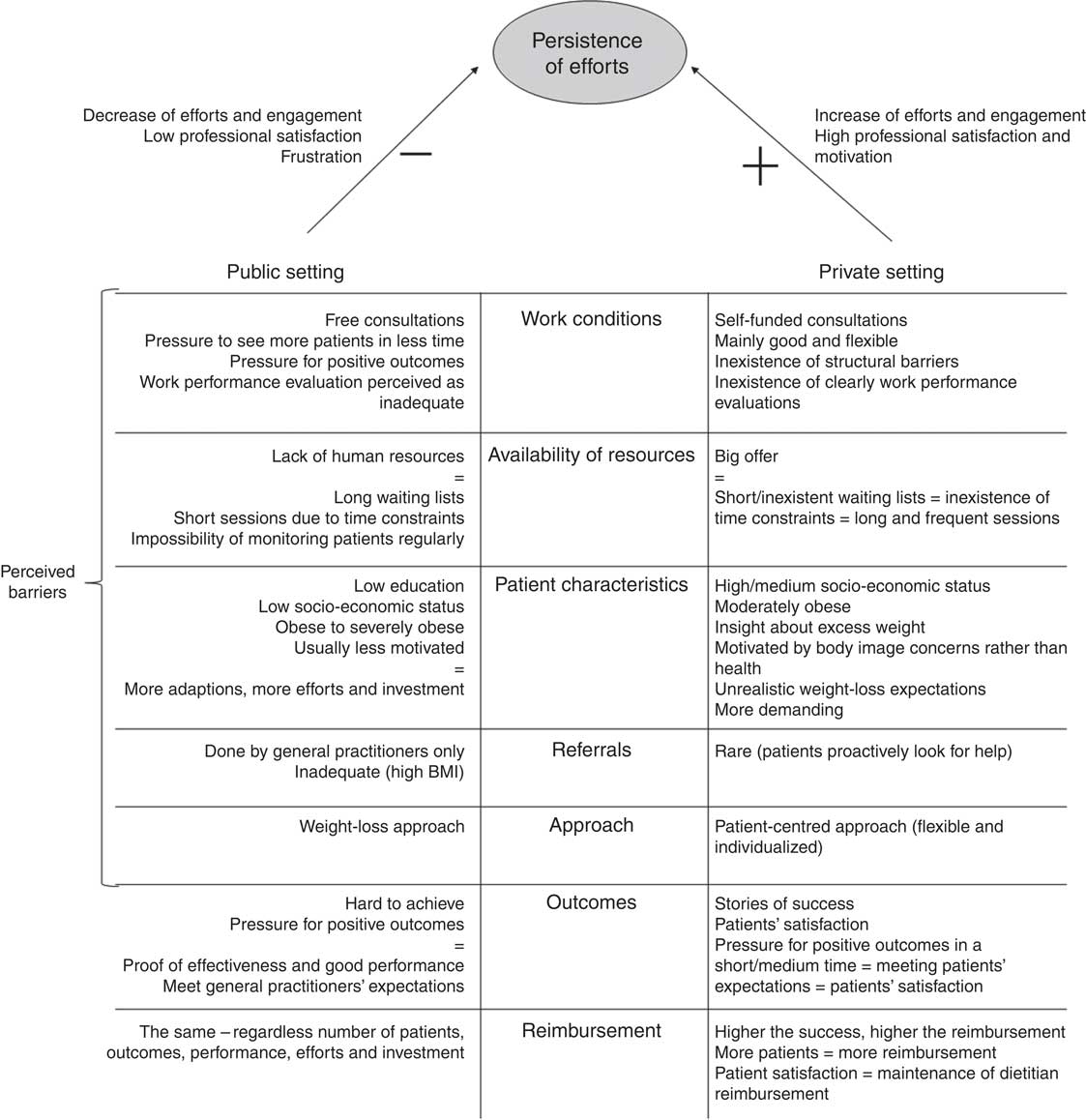

From the seventeen dietitians interviewed, ten worked in public primary care and seven in private settings. The participants’ characteristics are described in Table 2. ‘Persistence of efforts’ (Fig. 1) emerged as the main theme regardless of setting. However, this persistence seems to occur in different ways according to the setting in which dietitians are working, evidenced by an increase of efforts and investment in the private setting and a decrease in the public setting. Therefore, we divided the findings into similarities and differences, where, following a bottom-up approach, we describe the chain of sub-themes related to ‘persistence of efforts’ and summarize the contradictions emerging from both work contexts. The final and intermediate tree maps of the main findings concerning similarities between settings can be found in Figs 1–3, whereas Fig. 4 contains a map synthesizing the differences between public and private settings.

Fig. 1 Final tree map of the main theme, entitled ‘persistence of efforts’, derived from the analysis of the semi-structured interviews with Portuguese registered dietitians working in public primary-care (n 10) and private settings (n 7), January 2012–June 2014

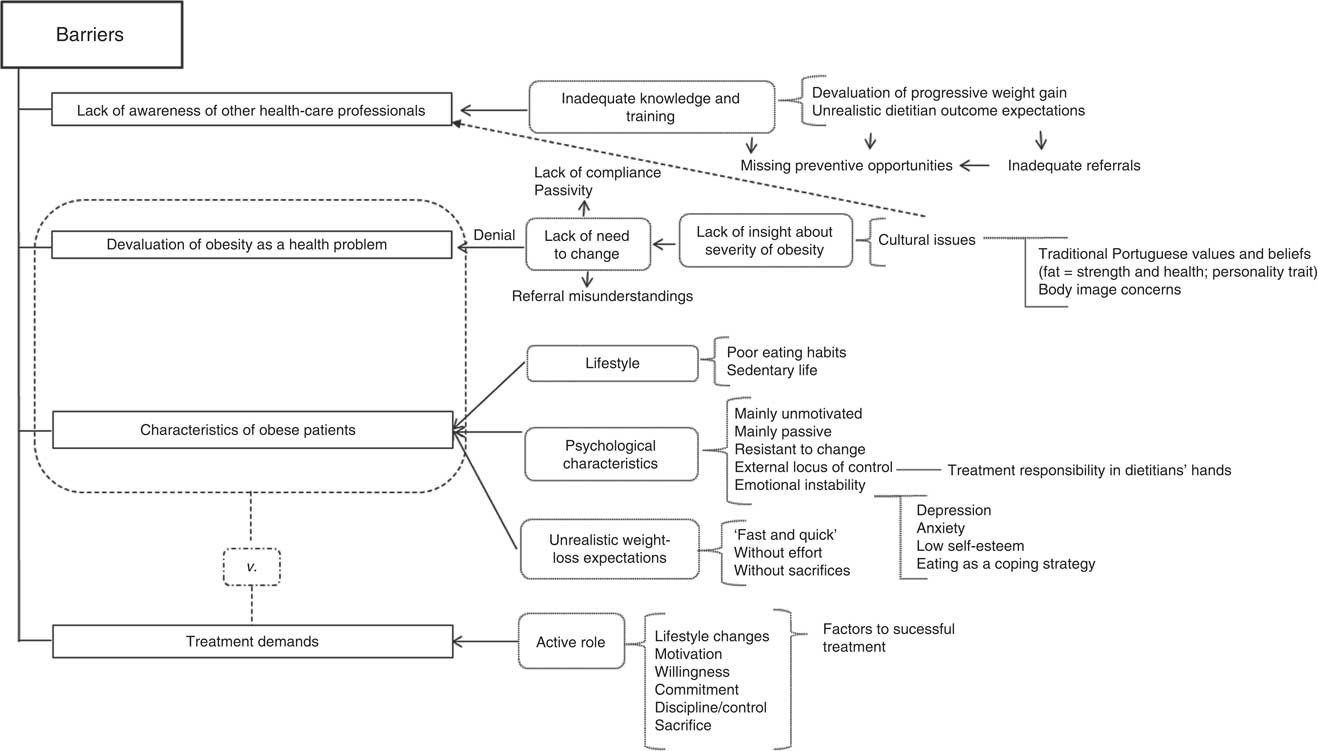

Fig. 2 Intermediate tree map of ‘barriers’ derived from the analysis of the semi-structured interviews with Portuguese registered dietitians working in public primary-care (n 10) and private settings (n 7), January 2012–June 2014

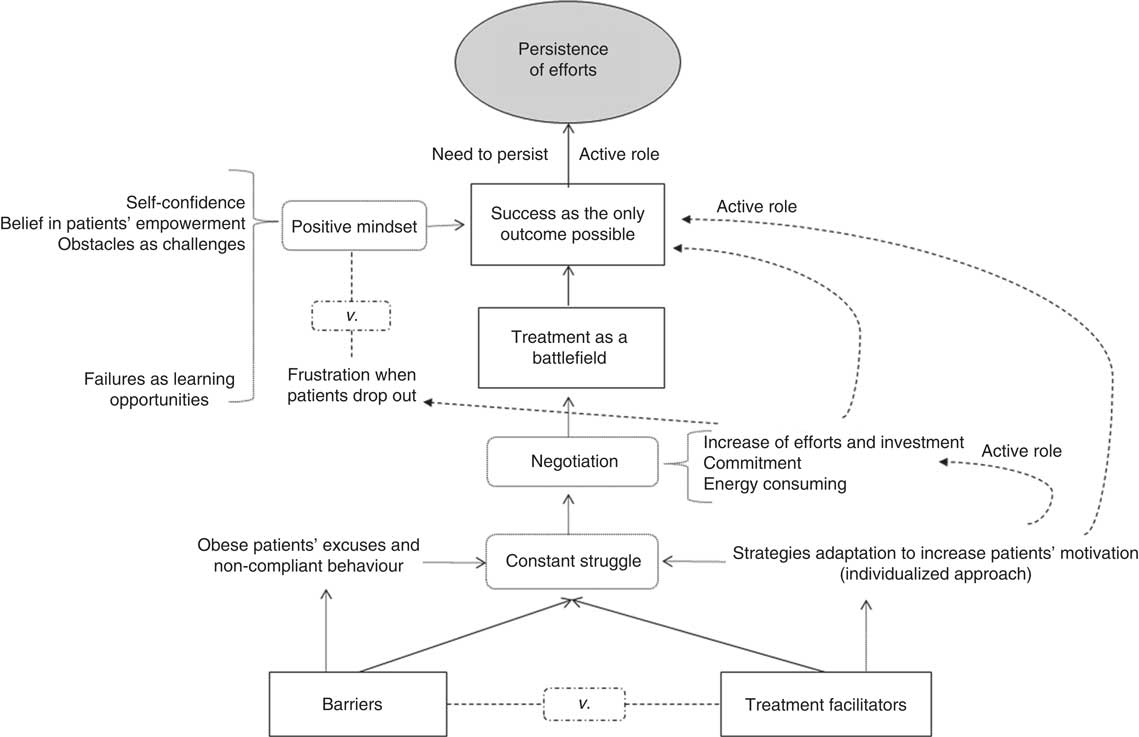

Fig. 3 Intermediate tree map of second-level sub-themes, ‘success as the only outcome possible’ and ‘treatment as a battlefield’, derived from the analysis of the semi-structured interviews with Portuguese registered dietitians working in public primary-care (n 10) and private settings (n 7), January 2012–June 2014

Fig. 4 Intermediate tree map of the differences between public and private settings derived from the analysis of the semi-structured interviews with Portuguese registered dietitians working in public primary-care (n 10) and private settings (n 7), January 2012–June 2014

Table 2 Characteristics of Portuguese registered dietitians from public primary-care (n 10) and private settings (n 7), January 2012–June 2014

Similarities between public primary-care and private settings

Barriers ( Fig. 2 )

Characteristics of obese patients

Although making an effort to avoid stigmatization, dietitians describe obese patients mainly as unmotivated and non-compliant, presenting a passive coping, holding unrealistic weight-loss expectations and misconceptions about food, perceiving lifestyle changes as a sacrifice, and therefore being unwilling to make time to diet or exercise. They want dietitians to take responsibility over the treatment, and they use to present psychological problems such as anxiety, depression and lack of self-control, using food as a coping strategy to deal with emotional impairment.

Devaluation of obesity as a health problem

Dietitians believe the lack of compliance and passivity of these patients occur because obese people do not perceive obesity as a health problem: they do not recognize the nature, consequences and severity of the problem, tend to deny their condition or perceive it as an unchangeable trait of their personality, and therefore do not understand the need to change and are not committed or motivated to do it. In dietitians’ opinion, this explains why many obese individuals feel sometimes offended about being referred or are very sceptical about this treatment option:

‘Some obese patients ask for help to lose weight “because I’m fat”, but being fat, for the majority of them, is not a health problem, it’s just a body image concern (...) they perceive the term “obesity” or “obese” as an insult or an expression with a negative connotation (...) most of them haven’t the slightest idea about what we do, don’t understand why they were referred to this service and feel upset because, suddenly, they have to deal with an extra problem and face a condition they don’t want to accept.’ (RD2)

Treatment demands

The previous characteristics are opposed to what dietitians report as being essential to a successful treatment. They emphasize the active role of patients in achieving the necessary lifestyle changes to lose weight, as well as motivation, willing to change, commitment, discipline and sacrifice:

‘They have to be willing to do sacrifices, they have to be really committed with themselves, with me, with the treatment, with their family, if they want results.’ (RD3)

Lack of awareness of other health-care professionals

Dietitians believe that general practitioners are not truly aware and well prepared to deal with the obesity pandemic, especially in primary care. According to dietitians, general practitioners are more worried with other diseases such as diabetes or hypertension than obesity, devaluing progressive weight gain and missing preventive opportunities by doing referrals mostly when patients are already obese rather than overweight. Therefore, positive outcomes are more difficult to achieve, which, in the participants’ opinion, creates in general practitioners a perception that nutrition counselling is not effective:

‘Of course, they [general practitioners] think we are not effective! What they are not understanding is that they are the ones reinforcing that belief! (…) They see the patient gaining weight consult after consult but they don’t ask for our advice. They just give them standard advices and don’t do the referral. They are not giving us opportunity to engage a nutrition preventive approach (…) when they came to us, they are already too heavy! Of course, the weight loss will take more time, the results won’t be visible in a short period of time – as they are used to achieve with medication – so, of course, they perceive us as ineffective!’ (RD3)

Treatment facilitators

Contrary to the described barriers, two different factors seem to facilitate dietitians’ work. On the one hand, dietitians perceive themselves as playing an active role in obesity treatment: although placing the treatment responsibility in patients’ hands, they believe they are the gatekeepers of change, being responsible for educating and motivating patients, feel confident about their performance and perceive themselves as the best-trained professionals to give nutrition advice. One the other hand, the consultation characteristics such as some flexibility of time of the encounter, the type of assessment and the strategies used, the opportunity given to patients talk about their difficulties, seem to create a positive environment favouring change and strengthening the dietitian–patient relationship. These characteristics were described by all participants as opposed to general practitioners’ consultations. However, when raising this topic, dietitians also started to naturally mention characteristics of encounters in public and private settings that led us to the perception and questioning of differences existing between these settings, resulting in the theme explored later in the present paper.

Treatment as a battlefield ( Fig. 3 )

Due to the conflict between the obstacles v. the facilitators of a successful treatment, dietitians feel they are continuously struggling with obese patients’ excuses for their non-compliant behaviour and resistance to change, frequently demystifying obese patients’ misconceptions about food, and constantly developing and adapting strategies to motivate these patients. ‘Negotiation’ emerges as a resolution of this fight but it is described as something involving a lot of effort, investment and commitment, leading to the perception of treatment as a difficult thing to do:

‘[I]t is really demanding. They are always presenting excuses (…) I feel I spend almost all my time giving them alternatives ... and they are still capable of presenting obstacles. We are constantly negotiating with them! We almost have to bet or make deals with the patients to motivate them.’ (RD10)

Success as the only outcome possible ( Fig. 3 )

This belief seems to drive dietitians’ action and role in obesity treatment. They not only trust in their own capacity in promoting the necessary behavioural changes, but they also believe that every patient is capable of achieving success in weight loss. Patients’ resistance to change is perceived as a challenge, requiring more effort, investment and creativity to adapt strategies, therefore leading to feelings of frustration when, even after all efforts, they drop out. However, these cases are perceived as opportunities for professional development rather than failures:

‘[O]f course, I think “What have I done wrong? Where did I fail? What can I do better in a next case?” I review the strategies, my involvement and engagement, sometimes I do some research (...) The most important thing is to learn from it, not take it personally and keep your motivation to always do your best.’ (RD5)

Persistence of efforts

In previous sub-themes, a persistent behaviour and viewpoint emerged throughout dietitians’ speeches, reflecting their perception as active agents in the weight-loss process. This ‘persistence of efforts’ is considered one of the main characteristics of dietitians’ work. It leads to repeated experiences of success that reinforce this persistence and promotes feelings of professional satisfaction and reward, increasing dietitians’ perception of self-efficacy. Because they are driven by this ‘need to persist’, they adjust standard treatments when they are not working by adopting a more individualized approach, valuing small behavioural changes instead of focusing only on the amount of weight lost, and adapting strategies and approaches that best fit patients’ characteristics, increasing the chances of patients’ adherence and achieving success:

‘We have to continuously motivate the patients, making them believe they can get it, that they will be succeed and always giving them motivational strategies to enhance long-term lifestyle changes even when you are tired of trying and the changes are very poor. It’s a constant battle but we need to use every possible strategy to keep the patient on the right path.’ (RD17)

Differences between public primary-care and private settings

Public primary-care setting

Dietitians working in this setting describe more intervention barriers and a range of stressful factors that seem to decrease their persistence of efforts and professional satisfaction. Dietitians feel pressure to achieve positive outcomes in a short period of time as a way of proving their effectiveness. By doing this, in terms of work performance evaluation, they demonstrate they are doing their job and, at the same time, they try to meet the expectations of the referring general practitioner, who also seems to hold unrealistic weight-loss expectations:

‘I don’t know what they are thinking about, when they send me a patient that has to lose 20 kg in three months to get an orthopaedic surgery! It is as if they don’t know that a sustainable healthy weight loss takes time! It is not the same thing as taking a pill and in a few days you start to see results. But this is what they are used to and it is want they want from us.’ (RD6)

This forces dietitians to prioritize the weight-loss approach and make them feel frustrated with the referrals done:

‘They see nutrition counselling as the last resource. I feel they only refer the patient when they are tired and sick of patients’ lack of adherence (…) when they come to us they are already very complicated cases of obesity, presenting poor motivation and compliance or even psychological problems that should be treated in the first place.’ (RD10)

The majority of patients also have low education and a low socio-economic status, which requires more investment to adapt the language and the strategies according to each patient’s budget. In some cases, dietitians consider that patients devalue the consultation because it is free of fees, which increases the feelings of frustration since dietitians do not see their efforts being recognized and feel that their waiting list is being poorly managed:

‘I sometimes think I gave an opportunity and wasted time and effort with someone that wasn’t caring or prepared to change instead of dedicating my time to someone that could actually be motivated and willing to change and would benefit from my help.’ (RD13)

In fact, the long waiting lists, resulting from a lack of human resources in this setting, appears as a big concern for these professionals. They would like to schedule more frequent and longer sessions (more than the average 30 or 40 min for a first session and 20 min for a follow-up session), but time constraints are not letting them do it:

‘[R]ight now I have patients waiting, at least, for six to nine months to get a first session (...) I really would like to see the patient again, two weeks after the first session or, at least, one time per month but it’s impossible! I do that in the beginning of the counselling but after noticing some changes I give him a dietary plan and star to follow him every two or three months ... some patients continue to comply, others don’t ... some just drop out or look for help in private setting.’ (RD6)

Although considering these barriers as continuous challenges in their workplaces, dietitians refer to feeling sometimes frustrated, professionally unrewarded, disappointed and less committed.

Private setting

This setting is characterized mainly by stories of success, inexistence of structural barriers, strong engagement and persistence of efforts, as well as client and professional satisfaction. The workplace conditions are mainly good, without clearly work performance evaluations, leading to a flexible, client-centred, small-changes approach. The waiting lists are short, which eliminates time pressures and creates more opportunities for weekly or monthly follow-up sessions with an average length of 45–60 min. Referrals are rare but professionals tend to collaborate with each other:

‘The main reason they flee from public to private setting is the waiting time. Not only for the first consultation but also for the following ones (...) There’s a lot of offer out there! If you don’t want to wait and it’s affordable to you, you can choose between left or right side of the street – you’ll definitely find a dietitian’s door there.’ (RD8)

‘On the contrary of public setting where they [obese patients] are always and exclusively referred by their GPs [general practitioners], here [private setting] they look for me and ask for my help. Referrals are rare … sometimes, the Internal Medicine or Surgery departments ask for my help and send me patients but it’s rare. More than 70 % of my clients looked themselves for help.’ (RD12)

The majority of clients are moderately obese, come from a high/medium socio-economic level and are more proactive by looking for help for themselves, reflecting greater awareness of their excess weight. However, that does not mean they are ready or willing to change. In dietitians’ opinion, because these clients are motivated mainly by body image issues rather than health, they tend to present even more unrealistic weight-loss expectations, looking for the ‘miracle’ and, sometimes, demanding treatment options such as weight-loss pills or other options that usually do not include lifestyle changes:

‘As far as I’m concerned, in public practice patients are less demanding, have problems in understanding the severity of obesity, have less education and all you are able to do is small changes. In private practice, people are more informed, have more education and are more demanding.’ (RD12)

‘Some of them just go from nutritionist to nutritionist until they find someone who gives them what they want: the weight-loss pills or the magic recipe.’ (RD9)

Because they are paying for the consultation themselves, private clients want to see their weight-loss expectations met, creating an urgency for positive outcomes that needs to be negotiated:

‘Paying means “I demand to see results”. They want to feel they are receiving value for money. If they are not satisfied, they simply drop out and look for nutrition advice in another private clinic. That’s why it is important to access client expectations in the beginning of the counselling and make them understand that their beliefs and expectations are not valid. Empathy and a good dietitian–client relationship are crucial in this setting. It sustains the counselling, helps clients to understand their problem and facilitates the goals negotiation.’ (RD14)

Nevertheless, this creates a pressure for outcomes in a short/medium period of time, resulting in dietitian bigger engagement and investment since achieving clients’ goals represents an increase in their satisfaction, further presence in the consultation and maintenance of dietitians’ reimbursement. In this context, patients seem to drop out only due to budget constraints or because their expectations are not met.

Discussion

In the present study we aimed to investigate, for the first time, the beliefs, attitudes and practices of Portuguese dietitians concerning obesity and obese patients and also identify differences between public primary-care and private settings, understand what might explain those differences and what implications they bring to practices and outcomes. Regardless of work context, ‘persistence of efforts’ emerged as the main characteristic of dietitians’ action in the treatment of obesity, with dietitians showing a strong belief not only in a successful treatment, but also in their ability to promote lifestyle changes. However, differences in reimbursement, work environment, perceived barriers, patient characteristics and availability of resources seem to contribute to differences in persistence of efforts according to the setting in which dietitians are working, evidenced by an increase of efforts and engagement in private practice and a decrease in public primary-care practice.

Similarly to other health-care providers( Reference Leverence, Williams and Sussman 23 ), the current study participants hold negative attitudes about obese patients deriving from feelings of frustration due to their lack of commitment and motivation( Reference Campbell and Crawford 3 , Reference Oberrieder 9 , Reference Stone and Werner 24 ). Negative feelings and stigmatization towards obese individuals among health-care professionals have been associated with perceptions of limited efficacy, little investment and avoidance behaviours( Reference Stone and Werner 24 – Reference Brownell and Puhl 27 ). However, contrary to what might be expected, dietitians present positive beliefs concerning treatment outcomes as well as favourable and appropriate practices, perceiving themselves as active agents in the treatment process( Reference Campbell and Crawford 3 , Reference Barr, Yarker and Levy-Milne 4 , Reference Harvey, Summerbell and Kirk 7 ). In addition, the experiences of success, even when related to small changes, reinforce dietitians’ self-efficacy and seem to trigger their positive belief in ‘success as the only outcome possible’, where persistence of efforts emerges as a key component of dietitians’ role. These findings are opposed to the ones reported by Campbell and Crawford( Reference Campbell and Crawford 3 ), because the Australian dietitians surveyed by those authors, although perceiving themselves as potential leaders in weight-loss treatment, are pessimistic regarding intervention outcomes. According to the findings of Stone and Werner( Reference Stone and Werner 24 ), who aimed to define different dimensions of professional stigma attached to obese patients, dietitians seem to be aware of the consequences that their negative attitudes and emotions may represent to the treatment (e.g. shorter sessions, decrease in efforts and engagement, blaming patients). Therefore, by recognizing the association between these emotional and behavioural aspects, they attempt to overcome their negative feelings by emphasizing their positive feelings and beliefs concerning their capacity and ability to achieve success (cognitive dimension), expressing therefore a strong willingness and desire to help patients even when they fail to follow professional advice, causing dietitians to experience frustration( Reference Stone and Werner 24 ). These assumptions are in line with dietitians’ persistence of efforts and empowerment of patients, as well as with the use of as many management strategies and approaches as possible to promote lifestyle changes. Participants tend to use a patient-centred approach which has shown positive health outcomes for a range of chronic diseases and settings( Reference Campbell and Crawford 3 , Reference Stewart 28 , Reference MacLellan and Berenbaum 29 ). They demonstrate flexibility, adopting the traditional portion prescription approach (not energy intake) or a lifestyle small-changes approach, according to intervention aims and patient characteristics( Reference Campbell and Crawford 3 , Reference Barr, Yarker and Levy-Milne 4 , Reference Zinn, Schofield and Hopkins 16 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer 30 ), confirming that ‘different approaches suit different people’( Reference Zinn, Schofield and Hopkins 16 ).

Similar to the findings of Chapman et al.( Reference Chapman, Sellaeg and Levy-milne 14 ), ‘negotiation’ emerged as a coping strategy to deal with the struggle between what dietitians consider to be the best treatment options for patients to succeed v. the barriers derived from obese patients’ unrealistic expectations and lack of adherence, enhancing patients’ motivation through education and the adjustment of goals and strategies (e.g. revision of the dietary plan). Therefore, the perception of ‘treatment as a difficult thing to do’ may derive from the lack of adequate training in behaviour change skills( Reference Rapoport and Perry 31 ). If the core role of dietitians is to help people to change their behaviours, these skills have become critical to the set required by these professionals to optimally manage weight loss. These findings shed light regarding current weaknesses in Portuguese nutrition programmes that fail in providing structured education and training concerning cognitive-behavioural strategies, motivational techniques and relapse prevention.

MacLellan and Berenbaum( Reference MacLellan and Berenbaum 29 ) indicated that the characteristics of the work environment intensify dietitians’ struggle, which was illustrated in our findings, especially in the public setting. The main limitation of effective practices and the reason for the decrease in persistence of efforts and job satisfaction in the public setting seem to derive from barriers coming from the organization of the health system( Reference Rapoport and Perry 31 ). The increase of obese patients in the health system requires the increase of available resources specialized in obesity treatment( Reference Harvey, Summerbell and Kirk 7 , Reference Cowburn and Summerbell 18 ) which, in our participants’ opinion, seems to be failing in the Portuguese health system’s organization. Also, individual sessions are still prevailing, leading to constraints in terms of duration and sustainability of sessions. The inclusion of behaviour change strategies requires a lengthier time frame of at least an hour and frequency of contact with the health professional is essential in the beginning of the counselling as well as in the maintenance of the weight lost( Reference Zinn, Schofield and Hopkins 16 , Reference Cowburn and Summerbell 18 ). Therefore, adherence and maintenance of weight loss in this setting may be compromised. In the same way, if multidisciplinary collaboration is considered a prerequisite for effective care, considerations about available resources should be taken into account in the development of health policies. However, the perceptions of general practitioners may be hindering effective multidisciplinary nutrition management in overweight and obesity( Reference Ball, Hughes and Leveritt 32 , Reference Nicholas, Pond and Roberts 33 ). Previous research has shown that, contrary to dietitians, whose nutrition counselling contributes to meaningful weight loss( Reference Zinn, Schofield and Hopkins 16 ), general practitioners’ nutrition care is superficial and ineffective( Reference Ball, Hughes and Leveritt 32 ). However, they continue to be the primary providers of nutrition care, even though they present inadequate knowledge, perceive dietetic counselling as ineffective and are resistant to do referrals( Reference Ball, Hughes and Leveritt 32 , Reference Wynn, Trudeau and Taunton 34 , Reference Mowe, Bosaeus and Rasmussen 35 ). General practitioners may require broader education and understanding of nutrition’s role in the treatment of obesity so that potential opportunities for patient nutrition management are not missed. Nevertheless, dietitians could also improve their communication with these professionals and help them to improve their knowledge and nutrition counselling strategies( Reference Kuppersmith and Wheeler 36 ).

On the contrary, the lack of barriers and limitations in private practice seems to be behind the successful treatments and the clients’ and professionals’ satisfaction, reinforcing the increase of dietitians’ persistence of efforts and perception of self-efficacy. Nevertheless, more research is needed to confirm the assumption that the private setting is more successful than the public setting, since it is based on participants’ perceptions which could be biased due to (non) existence of structured barriers and differences in obese patients’ profile. However, similar to the findings of Brown et al.( Reference Brown, Mitchell and Williams 19 ), financial factors seem to be an important reason driving the work in private practice. Keeping clients motivated and satisfied and meeting their weight-loss expectations means clients’ attendance at further consultations, avoids dropouts and guarantees dietitians’ reimbursement. In this setting, persistence of efforts is seen to have the potential for higher remuneration; whereas in the public setting, no matter how many patients dietitians see or how efficient they are, their reimbursement will always be the same. More research is needed to clarify these findings.

Strengths and limitations

The use of a sound qualitative framework with detailed description of the procedures of collecting and analysing data, the reflexive diaries kept by the main interviewer, the use of the constant comparative method, and the shared comments, discussion and revision during analysis enhanced the rigour and trustworthiness of the findings and allow further decisions concerning transferability. However, the generalizability of these findings requires verification in larger and more diverse samples. The differences in age and years of experience between interviewees from the public and private settings may also constitute a limitation, since they could have biased the views about obesity and the description of the setting and the practices. The study is also limited in geographical scope to the north of Portugal.

Conclusion and implications for research and practice

Although no national guidelines exist regarding the management of obesity, Portuguese dietitians present not only actions in accordance with the main international guidelines but also a positive mindset about obesity treatment outcomes. However, the findings highlight the need for health authorities to acknowledge the constraints to provision of weight management services within the public health-care system and to develop policies that address the improvement of health-care professionals’ education, increase the available recourses, and enhance interdisciplinary collaboration where physicians and other health professionals support each other and refer obese patients to dietitians routinely. A dietetic guideline development initiative would ideally address some additional factors: health professionals’ role in practice decisions, organizational and resource considerations, the targeting of specific practices (e.g. screening, advice giving, appropriate referral practices), long-term management strategies and dietetic training. In the same way, the organization of the health system should take account of collaborations with the private setting since it seems to meet the gap in public services in terms of offer (number of dietitians), less barriers, short waiting lists and best environment, taking some of the pressure off predominantly in public services. However, as mentioned previously, more research is needed concerning the effectiveness in these settings, barriers in health professionals’ collaboration and the influence of reimbursement on dietitians’ practices.

Finally, in the present study, dietitians focused on their own beliefs, attitudes and practices and on the face-to-face interventions developed with obese patients at an individual level, highlighting their own role in treatment outcomes as well as the role of patients’ behaviour in the process of weight loss. Their speeches were focused on their actions and patients’ behaviours rather than external factors contributing to patients’ weight problem or influencing dietitians’ actions. However, the food environment, meaning both food prepared and consumed at home as well as out-of-home sources, is one of the elements fuelling the obesity pandemic that must be considered when discussing obesity interventions( Reference Townshend and Lake 37 ). Because this topic was not explored in depth, it is important to develop further research exploring dietitians’ perceptions of the food environment, how it might represent an obstacle in their individual practice and how they handle it. Also, in the same way dietitians are at the forefront of providing nutrition management at an individual level, they also have a role to play at community and society levels. Future research should also address dietitians’ role perception in the collaboration and development of health policies related to the food environment.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank all participants interviewed for their time and contribution. They also would like to acknowledge the support from the Faculty of Psychology and Education of the University of Porto, where the study was conducted. Financial support: This study was partially conducted at the Psychology Research Centre (UID/PSI/01662/2013), University of Minho, and supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology and the Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education through national funds and co-financed by FEDER through COMPETE2020 under the PT2020 Partnership Agreement (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007653). The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: The authors’ contributions were as follows. Literature review: F.V.T., J.L.P.-R. and A.M. Ethics application: J.L.P.-R. Contacting participants: F.V.T., J.L.P.-R. and A.M. Conducting interviews: F.V.T. Transcriptions: F.V.T. First framework: F.V.T. Progressive analysis and interpretation: F.V.T., J.L.P.-R. and A.M. Final discussion of the interpretation and tree maps: F.V.T., J.L.P.-R. and A.M. Writing the manuscript: F.V.T. Commenting on manuscript drafts: J.L.P.-R. and A.M. Proof-reading/formatting the manuscript: J.L.P.-R. and A.M. Ethics of human subject participation: The study was approved by the Health Committee of Ethics of the North of Portugal and by the Ethics Board of the University of Porto. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.