In 2015, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau appointed a gender-equal cabinet and proclaimed it a “cabinet that looks like Canada.” It included an equal number of men and women but excluded Chinese and Black Canadians, the country’s first- and third-largest racialized groups. 1 Notably, although the government’s commitment to gender parity was explicit, there was no parallel promise to increase racialized Canadians’ presence in cabinet. The presence of women instead stood in for the inclusion of other historically marginalized groups. The government’s elevation of gender equality is not unique. Women have often acquired political rights and institutional power before racialized others (Reid Reference Reid2004; Sangster Reference Sangster2018; Wolbrecht and Corder Reference Wolbrecht and Corder2020). For example, in Canada, women were granted the right to vote in federal elections in 1918, but the franchise excluded Asian Canadians until 1948, and it was not until 1960 that federal voting rights were unconditionally extended to First Nations people (Elections Canada 2021).

Likewise, political scientists have often looked first at gender and then at other equity-seeking groups. In the literature on descriptive representation, which is the focus of this study, there is now a large body of research on women candidates’ emergence and selection (Ashe Reference Ashe2020; Cross and Pruysers Reference Cross and Pruysers2019; Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2013; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2010; Kenny Reference Kenny2013; Kenny and Verge Reference Kenny and Verge2016; Medeiros, Forest, and Erl Reference Medeiros, Forest and Erl2019). However, we know much less about how race shapes candidate emergence and selection (although see Branton Reference Branton2008; Ocampo and Ray Reference Ocampo and Ray2020). One recent study argues that “the interaction between ethnicity and candidate nomination is seldom articulated” (Janssen, Erzeel, and Celis Reference Janssen, Erzeel and Celis2020, 1), while Lawless (Reference Lawless2011, 5) concludes that “almost no research specifically addresses race or ethnicity in the candidate emergence process.” As a result, (white) women’s representation has been viewed as “the best empirical proxy for representation overall” (Rahat, Hazan, and Katz Reference Rahat, Hazan and Katz2008, 669).

The relative absence of race from candidate studies has historical and methodological roots. Early on, because of formal and informal exclusions, racialized individuals were simply not present in elected institutions, and thus they were absent from their study. Now, racial diversity in politics has increased, but the persistent lack of data on race remains an empirical problem. There is also very little district-level data on the identities of candidates in electoral primaries or party nominations, which limits most research to declared candidacies and the final stages of candidate selection and election (e.g., Andrew et al. Reference Andrew, Biles, Siemiatycki and Tolley2008; Black Reference Black2020; Hughes Reference Hughes2013b). Therefore, we know very little about the racialized or intersectional processes that precede candidate selection and election.

The growth of intersectional frameworks marked a shift in the gender and politics literature. Scholars began to produce more multiple axis research (Reingold, Haynie, and Widner Reference Reingold, Haynie and Widner2021) and to collect data on identities other than gender. Even so, studies of race and intersectionality in candidate emergence and selection still focus primarily on the United States and, to a lesser extent, Europe and Britain (e.g., Brown Reference Brown2014; Celis and Erzeel Reference Celis and Erzeel2015; Freidenvall Reference Freidenvall2016; Holman and Schneider Reference Holman and Schneider2018; Janssen, Erzeel, and Celis Reference Janssen, Erzeel and Celis2020; Jenichen Reference Jenichen2020; Krook and Nugent Reference Krook and Nugent2016; Mügge Reference Mügge2016; Shah Reference Shah2014, Reference Shah2015; Shah, Scott, and Juenke Reference Shah, Scott and Juenke2018; Shames Reference Shames2015; Silva and Skulley Reference Silva and Skulley2019; Van Trappen Reference Van Trappen2021). In many other contexts, there have been almost no intersectional studies of candidate emergence and selection.

The present study asks whether (and how) gender, race, and intersectionality shape each stage of legislative recruitment. I argue that when we use gender as a proxy for race, we miss key distinctions in the legislative recruitment of racialized minorities and women of color. To do so, I constructed an original data set containing the race and gender of more than 800 political aspirants in the 2015 Canadian election. Casting backward to the pre-candidate stage, the article helps pinpoint the stage at which political opportunities widen or narrow and, by extension, when electoral underrepresentation commences. The analysis identifies variations in these pathways depending on the aspirant’s race, gender, or intersectional identities. This evidence shows that women, regardless of race, aspire to political office at roughly the same rate but in far lower numbers than their male counterparts. By adopting an intersectional perspective, I cast new light on their political pathways showing that experiences diverge at the point of party selection. Whereas opportunities for white women open when parties choose their candidates, they instead narrow for racialized minorities and especially for racialized women. I suggest that while parties have begun to address gender gaps in legislative recruitment, they do so in ways that are insufficiently attentive to race and intersectionality. As a result, party efforts to diversify candidate slates and legislatures largely benefit white women, leaving racialized women doubly burdened by their gender and their race. The article’s findings help generate new theoretical and empirical directions for future research.

Theoretical Framework

Race, Gender, and Intersectionality in Politics

In her pathbreaking work on the “politics of presence,” Anne Phillips (Reference Phillips1998) suggests that an elected assembly’s demographic composition should reflect the composition of the population it serves. The correspondence between a group’s presence in the population and its presence in elected office is referred to as descriptive representation. Formative works in gender, race, ethnicity, and politics interrogate the discrepancy between the ideal of descriptive representation and the realities of political inequality and exclusion (Htun Reference Htun2004; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Mügge et al. Reference Mügge, Montoya, Emejulu and Weldon2018). This literature identifies the processes and mechanisms that can ameliorate electoral underrepresentation, including quotas, electoral rule changes, and more diverse party selectorates (Cheng and Tavits Reference Cheng and Tavits2011; Hughes Reference Hughes2011; Krook and Norris Reference Krook and Norris2014; Ocampo Reference Ocampo2018).

Despite the emergence of this research, Hawkesworth (Reference Hawkesworth2016, 2) argues that political science continues to present a “disembodied account of politics in which race, gender, ethnicity, nationality, and sexuality play no central role.” Feminist scholars have critiqued the masculinist orientation of politics (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2016), and in response, gender has been added to the study of legislatures, political parties, and other institutions. However, just as the prototypical politician has historically been coded as male, political experiences have also been coded as white. Research on race, while growing, remains on the margin, and gendered subjects are often racially unmarked or implicitly white (Brown Reference Brown2014). To date, the call for “multiple axis thinking” and intersectional political institutions has not yet been fully realized (Krook and Nugent Reference Krook and Nugent2016).

Kimberlé Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw1989) developed the concept of intersectionality, arguing that to understand the experiences of Black women, we must look not only at their race or at their gender, but at their combined, interlocking identities. Intersectionality is often thought of as a complement to mainstream feminist theory, but it emerged fundamentally as a critique of essentialist notions of femininity that position gender as determinative of women’s fate (hooks Reference hooks2014). Individuals encounter multiple and overlapping forms of oppression, and these experiences are shaped by power structures embedded in society, politics, and the economy (Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2015; Brown Reference Brown2014; Simien Reference Simien2007; Smooth Reference Smooth2006). Intersectional approaches are thus power driven, not variable driven: they require the recognition of systemic hierarchies, not simply the addition of demographic controls to regression models (Hancock Reference Hancock2007).

Political science’s engagement with intersectionality has been more recent (see Mügge et al. Reference Mügge, Montoya, Emejulu and Weldon2018, for an overview of this history). While Norris and Lovenduski’s (Reference Norris and Lovenduski1995) canonical study of political recruitment looked at both gender and race, the approach was not intersectional, a feature that one of the authors later noted was “a product of its time” (Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2016). In Canada, researchers have employed intersectional frameworks (Dhamoon Reference Dhamoon2009; Hankivsky and Mussell Reference Hankivsky and Mussell2018; Labelle Reference Labelle2021; Nath, Tungohan, and Gaucher Reference Nath, Tungohan and Gaucher2018), but these inroads have not yet translated into the study of legislative recruitment, where women’s political pathways remain the primary focus (Cheng and Tavits Reference Cheng and Tavits2011; Cross and Pruysers Reference Cross and Pruysers2019; Medeiros, Forest, and Erl Reference Medeiros, Forest and Erl2019). Some Canadian work on candidate emergence has looked at race and gender, but not intersectionally (Andrew et al. Reference Andrew, Biles, Siemiatycki and Tolley2008; Ashe and Stewart Reference Ashe and Stewart2012), or the focus has excluded the pre-candidate stage (Black Reference Black, Tremblay and Trimble2003). As a result, political science has little to say about the legislative recruitment of racialized minorities in Canada and of racialized women in particular.

Methodologically, there is simply less data on racialized minorities’ political representation, not just in Canada but worldwide. Although there are high-level counts of gender representation in world parliaments (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2019), data collection on other minority groups has been less systematic (although see Hughes Reference Hughes2013b). Even when race is considered, gender often remains at the forefront—the so-called master variable—meaning there are data on women of color, but not men of color or racialized minorities more generally (Center for American Women and Politics 2019). Perhaps this is because women have a longer history of equity seeking in many countries, and feminist organizing has helped solidify and institutionalize these gains. Moreover, the definition of “minority” is slippery and varies across countries (Fearon Reference Fearon2003), and the markers are sometimes less evident than those related to gender, which impedes data collection (Hughes Reference Hughes2013a). Political parties frequently do not track the data themselves or release it only in aggregate form, and almost never for candidates at the party primary or nomination stage. There is thus a dearth of district-level data on candidate demographics. To fill this gap, some researchers have conducted surveys of candidates, but low response rates result in substantial missing data (Andrew et al. Reference Andrew, Biles, Siemiatycki and Tolley2008; Walgrave and Joly Reference Walgrave and Joly2018). Researchers are largely left to classify candidates’ backgrounds on their own, relying on published biographies, genealogical methods, or inference, methods that are labor-intensive and also raise questions about the scholar’s role in ascription (Shah and Davis Reference Shah and Davis2017). In some contexts, automated coding techniques hold some promise, but data reliability remains an issue (Reith, Paxton, and Hughes Reference Reith, Paxton and Hughes2016).

Conceptually, we might intuit that because gender and race are both ascriptive markers of exclusion, they provide an equivalent basis from which to understand political experiences and outcomes (Williams Reference Williams1998). However, within the same country, women and racialized minorities often experience different levels of political underrepresentation, suggesting the groups are not analogous (Andrew et al. Reference Andrew, Biles, Siemiatycki and Tolley2008). There is also evidence elsewhere that party recruiters prioritize gender equality over the representation of other diversities (Freidenvall Reference Freidenvall2016). Moreover, whereas women form a majority in most electoral districts, the proportion of minorities fluctuates, and minority candidate emergence is constrained by these population patterns. Some countries, including the United States, draw district boundaries to ensure that particular minority groups form a majority, and these are the districts in which minority candidates tend to run (Shah Reference Shah2015; Shah, Scott, and Juenke Reference Shah, Scott and Juenke2018). But even in countries without these interventions, such as Canada, racialized minorities tend to reside in a narrower cluster of districts than is the case for women (Tolley Reference Tolley2019). Finally, there is the argument that racialized women are a distinct politicized group and should be the focus of study in their own right (Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2021; Shames Reference Shames2015). Research on media coverage, quota adoption, voter behavior, and other domains (e.g., Bird et al. Reference Bird, Jackson, McGregor, Moore and Stephenson2016; Gershon Reference Gershon2012; Htun Reference Htun2004; Ward Reference Ward, Brown and Gershon2016) reveals that race and gender can have divergent effects on outcomes. This article therefore asks about the separate and combined impact of these identities in candidate recruitment.

Legislative Recruitment

In democratic contexts, legislative recruitment is the process of advancing through the stages of selection for elected office. Legislative recruitment includes four key steps (see Figure 1). First, candidates must be eligible for office, which usually includes criteria related to age, residency, and citizenship. Second, they must aspire to office and put themselves forward, usually in a primary for the party’s nomination. Third, they must win the primary to become the nominated candidate for their party. And fourth, they must be elected as legislators. Thus, there are three main points of selection: oneself (to emerge as an aspirant), one’s party (to be selected as a candidate), and one’s voters (to be elected as a legislator).

Figure 1. Legislative recruitment process. Adapted from Matland (Reference Matland1999, Reference Matland, Ballington and Kham2005) and Van Trappen, Vandeleene, and Wauters (Reference Van Trappen, Vandeleene and Wauters2021)

At each stage of legislative recruitment, there is a declining number of participants in the pool of prospective candidates. The literature consistently finds that the numbers of women and racialized minorities are disproportionately low at the final stage—election as a legislator—a phenomenon referred to as “the law of increasing disproportion” (Putnam Reference Putnam1976), “the higher, the fewer,” (Bashevkin Reference Bashevkin1985), and the “law of minority attrition” (Taagepera Reference Taagepera, Rule and Zimmerman1994). Although this general pattern is largely established, it is not clear when in the legislative recruitment process the narrowing of political opportunities occurs and how this is differentiated by race and/or gender.

Legislative recruitment is often operationalized using the metaphor of supply and demand (Krook Reference Krook2010). On the supply side are the pools of individuals who are eligible for and aspire to political office. Personal resources, political ambition, and rules about who can run for office structure the population of these pools. On the demand side, party selectors (who choose the candidates) and voters (who ultimately select the legislators) determine whether prospective candidates move forward in their quest for elected office. Each stage of legislative recruitment is an opportunity to attain or fall short of descriptive representation, and the demographic composition of legislatures is influenced by factors on both the supply and demand sides.

The research on women’s legislative recruitment suggests that the gender gap in candidate supply is driven by women’s lower levels of political ambition, more limited economic resources, time constraints, and concerns about harassment as candidates and elected representatives (Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2010). Meanwhile, the composition of party selectorates and their candidate preferences help shape the candidate pool in ways that are gendered (Ashe and Stewart Reference Ashe and Stewart2012; Cheng and Tavits Reference Cheng and Tavits2011).

When race has been the focus of research on legislative recruitment, it appears that the pathway for racialized candidates is different from that suggested in the literature on women candidates (Juenke and Shah Reference Juenke and Shah2016; Shah Reference Shah2014, Reference Shah2015; Shah, Scott, and Juenke Reference Shah, Scott and Juenke2018). On the supply side, there is evidence women’s underrepresentation is driven in part by their lower levels of political ambition, but Black political aspirants in the United States have shown high levels of political ambition (Shah Reference Shah2014, Reference Shah2015). Party gatekeepers underestimate the electoral potential of both women and racialized candidates, and they are less likely to recruit them than white men (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2013; Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Oskarsson and Vernby2015; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2006a). Local party chairs in the United States tend to view minority candidates as less viable than white candidates but believe women are as viable as men (Doherty, Dowling, and Miller Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2019). Racialized candidates report receiving less encouragement from party elites than other candidates (Moncrief, Squire, and Jewell Reference Moncrief, Squire and Jewell2001), but this difference might be offset by their higher levels of political ambition (Shah Reference Shah2015). Even when parties do select racialized candidates, they are most likely to be nominated in a small cluster of districts with large minority populations (Farrer and Zingher Reference Farrer and Zingher2018; Sobolewska Reference Sobolewska2013; Tolley Reference Tolley2019), while women are more likely than men to be nominated in less competitive electoral districts (Thomas and Bodet Reference Thomas and Bodet2013).

When race and gender intersect, the effects on legislative recruitment can be both contradictory and complementary. On the one hand, racialized women might be viewed as politically attractive candidates because they are able to capitalize on their race and gender to appeal to both women and minorities, a phenomenon referred to as the “complementarity advantage” (Celis and Erzeel Reference Celis and Erzeel2015). Party elites might view the selection of racialized women as an opportunity to “kill two birds with one stone,” while preserving white male power through the exclusion of racialized men (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2013; Celis et al. Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damstra2014; Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003; Hughes Reference Hughes2011). On the other hand, racialized women could face a “double disadvantage” or “double burden” (Black and Erickson Reference Black and Erickson2006; Celis et al. Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damstra2014; Shah, Scott, and Juenke Reference Shah, Scott and Juenke2018) because efforts to increase gender equality primarily advantage white women (Hancock Reference Hancock2009).

Women’s equality initiatives have often included only limited attention to intersectionality (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damstra2014), and thus efforts to increase representation tend to focus only on gender, to the exclusion of other identities. This pattern persists even though, in the United States, women of color are less likely than other women to be recruited (Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2006b), and they may even be actively discouraged from entering politics (Sanbonmatsu, Carroll, and Walsh Reference Sanbonmatsu, Carroll and Walsh2009). Moreover, in a number of contexts, including Canada, parties’ affirmative action measures often prioritize gender (not race) as the key dimension of interest (Freidenvall Reference Freidenvall2016; Liberal Party of Canada 2021).

Case Selection, Method, and Data

Culture is gendered (and raced), so understandings of representation are context specific (Liu Reference Liu2018). I extend the study of legislative recruitment to Canada, a case that is less prominent in the literature. Colonized by the British and French but geographically and economically intertwined with the United States, Canada is influenced by American and European norms and traditions, and therefore it exists at a midway point between countries that dominate the literature on candidate selection. Canada is also an informative case study because of conflicting racial and gender logics. Racial and gender equality rights are enumerated in the country’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and there is an official policy of multiculturalism that includes state-funded support for anti-racism and equality initiatives. These achievements foretell a country that is open to diversity.

At the same time, there is evidence of some resistance. Women of color were not elected to the House of Commons until 1993, and they currently hold just 5% of seats, compared to 24% for white women (Tolley, Bosley, and Duncan Reference Tolley, Bosley, aba Duncan, Pammett and Dornan2022). There are no legislated quotas, and a proposal to enforce a financial penalty on parties that nominate too few women candidates was quashed by Parliament in 2016. Moreover, racialized Canadians have only recently been elevated to permanent positions of party leadership. 2 Canadian political science has largely neglected the study of race, tending to privilege territorial explanations and focus on differences related to region, language, religion, and ethnicity (Nath Reference Nath2011; Nath, Tungohan, and Gaucher Reference Nath, Tungohan and Gaucher2018; Thompson Reference Thompson2008). These competing logics provide an excellent vantage point from which to examine legislative recruitment and to theorize its gendered, racialized, and intersectional dynamics. Although the empirical data are country specific, the theoretical motivations are broader reaching.

All of Canada’s major parties use direct elections to choose the candidates who will represent them in the country’s 338 federal electoral districts. Candidate selection in Canada is largely a party affair, involving only the small percentage of Canadians—some estimates suggest as low as 2%—who hold a party membership (Cross Reference Cross, van Haute and Gauja2015). Local party members in each district vote in the party primaries that ultimately select the party candidates; in Canada, these are usually called nomination contests. Candidates from each party then go on to run in single-member district plurality elections; the winning candidates become members of Parliament (MPs). Local party associations in each federal electoral district oversee candidate nominations. Although the federal parties set overarching rules and can veto a local association’s choice or impose their own, generally local party members choose who is on the ballot, and these selectors therefore have considerable control over the diversification of the candidate slate (Koop and Bittner Reference Koop and Bittner2011; Pruysers and Cross Reference Pruysers and Cross2016; Thomas and Morden Reference Thomas and Morden2019).

Federally, there are roughly two dozen registered political parties in Canada, but many do not run a full slate of candidates: they may only run candidates in a single province, or they have a very limited presence in the House of Commons. Therefore, I focus on the three largest, most electorally competitive parties: the Liberal Party, the Conservative Party, and the New Democratic Party (NDP). In their work on candidate selection, Pruysers and Cross (Reference Pruysers and Cross2016, 782) position these three parties as the “major players.” 3

The 2015 Canadian election followed a redistribution of electoral boundaries, which added new districts and reconfigured several existing ones. Some new districts contained parts that had previously belonged to other districts. Rather than protecting incumbent MPs from nomination contests, which had been the practice in past elections, all the major parties signaled they would support “open nomination contests” in every district; this practice was either modified or abandoned by the major parties in the subsequent 2019 election. The 2015 election thus gives insight into candidate selection in a best-case scenario, one in which the advantages wielded by incumbents would theoretically be dulled, and we can observe candidate selection in its most unadulterated form.

Women candidates are evenly distributed across districts, but the distribution of racialized candidates is more skewed, and many districts have very small racialized populations. A census of districts would result in the inclusion of a large number of districts where we cannot reasonably expect many racialized candidates to emerge quite simply because they do not live there. 4 Therefore, the research design focuses on districts with racialized populations of more than 15%; this percentage is the average racialized population across all electoral districts. There are 136 federal electoral districts above this threshold. 5 These are the most racially diverse districts in the country. In 2015, just 16 racialized candidates ran for the major parties in the districts outside this sample. From these districts, voters elected 136 MPs, who emerged from a slate of 408 electoral candidates; these candidates were selected from a pool of 814 aspirants. I focus on the 801 white and racialized aspirants, excluding those identified as Indigenous. 6

I constructed an original data set drawn from two main sources. First, I used an Elections Canada database to construct a list of aspirants for party nomination; parties are obligated to report these details to the election agency, although they do not always do so. In these cases, I gathered the names of aspirants from party news releases, local media stories, and other sources. Second, I used biographical materials and social media (which often includes candidates’ own self-identification), as well as photographs and surname or pronoun analysis to determine the demographic background of the individuals who ran for the nomination. I required a positive identification from at least two sources before coding an aspirant’s race or gender. No nonbinary candidates were identified, and aspirants were therefore coded as man or woman, and as white or racialized. For 19 aspirants, their race was unknown or unclear; they are excluded from analyses of race but included in analyses of gender.

This approach to coding candidates’ backgrounds is relatively common (Andrew et al. Reference Andrew, Biles, Siemiatycki and Tolley2008; Black Reference Black2017; Shah and Davis Reference Shah and Davis2017), but it comes with methodological, conceptual, and normative limitations. First, as Thompson (Reference Thompson2008, 536) points out, it uses “imposed racial identity based on visible morphological or phenological attributes, giving the power of racial definition to the observer and objectifying the racial subject” (see also Thompson Reference Thompson2016). This criticism is one that scholars have struggled with, in part because response rates to surveys asking political elites how they identify are sometimes so low that 50% or more of the cells are coded as missing data (Andrew et al. Reference Andrew, Biles, Siemiatycki and Tolley2008; Walgrave and Joly Reference Walgrave and Joly2018). Given how few racialized minorities serve in elected office and how little we know about their pathways to politics, these gaps pose a serious impediment to analysis. Were we to rely solely on self-identification, we would arrive at a very partial view of diversity in politics.

Second, there are clear limitations to macro-level “white” and “racialized” categories. Debates about racial classification cut across all social research, and they are not easily resolved, particularly in empirical studies (Song Reference Song2018; Thompson Reference Thompson2016). Initially, I set out to code more fine-grained racial identifications (e.g., Black, South Asian, Chinese Canadian). However, specific racial identifications are rarely reported in biographies or news reports, so confirmatory evidence often came from photographs and name analysis, and it is difficult to derive reliable coding on racialized subgroups from the latter sources. In the interest of accuracy, I have excluded subgroup data from the analyses, but this unfortunately elides some differences within and among racialized groups and simplifies how lived experiences translate into unique modes of political engagement among women of color and across racialized groups (Gillespie and Brown Reference Gillespie and Brown2019). My approach should not be interpreted as a legitimation of these limitations, but rather as a strategic deployment that provides a necessary but imperfect (and partial) corrective to existing data gaps.

Findings

An essential goal of this study is to understand how gender and race shape each stage of legislative recruitment, with due attention to the rich context in which these relationships emerge. My analytical strategy is therefore purposefully descriptive. I use three measures to assess the representation of gender, race, and their intersections in legislative recruitment. First, I look at each group’s relative share of the eligible, aspirant, candidate, and legislator pools. This measure helps us understand a group’s proportion of the pool in relation to comparator groups. Second, I look at each group’s rate of success at key selection points, which helps us understand who is most likely to emerge victorious at each stage. Third, I assess each group’s descriptive over- and underrepresentation, a measure that compares their presence in the aspirant, candidate, and legislator pools to their presence in the population. This is expressed as a representation ratio.

Relative Share of the Pool

Figure 2 shows each group’s relative share of the eligible, aspirant, candidate, and legislator pools. 7 The top two panels provide aggregate patterns by gender and by race. As the upper-right panel shows, racialized Canadians aspire to office in proportions that rival their presence in the eligible population, but by Election Day, their share of seats in the legislature falls below. This narrowing is less evident for women candidates. As the upper-left quadrant illustrates, once women aspire to office, they fare somewhat better than racialized candidates. Parties may help augment women’s electoral opportunities when they select candidates, but women’s presence tapers off on Election Day. In short, as women and racialized Canadians move through the stages of legislative recruitment, the political pipeline narrows, whereas it widens for those who are white or male.

Figure 2. Legislative recruitment by relative share of the pool. Panels depict a group’s share of the total pool at each stage

Consistent with research on gendered political ambition, Figure 2 confirms that male aspirants outnumber women. The panel in the upper-left quadrant shows that the proportion of women aspirants is far below their presence in the population, a pattern not mirrored by racialized minorities, whose presence in the aspirant pool is nearly on par with their presence in the population. In the aggregate, therefore, racialized Canadians aspire to politics at rates that roughly match their presence in the population, suggesting the bottleneck is not at the aspirant stage. This finding is consistent with research on Black political aspirants in the United States (Shah Reference Shah2015). The bottleneck instead appears when party selectorates are choosing their candidate and then, later, when the electorate chooses their legislator. 8

The lower-left panel of Figure 2, which compares racialized men and women, shows that high levels of political ambition are driven by racialized men, whose presence in the aspirant pool outpaces their presence in the pool of eligibles. This is not the case for racialized women. At the beginning of the political pipeline, racialized men’s trajectory is closer to that of white men than to that of racialized women, but the pattern diverges at the party selectorate stage.

When parties select candidates from the aspirants who have come forward, white women and men are chosen in higher proportions than at the preceding stage, but the opposite is true for racialized aspirants. Racialized men’s chances diminish at the party selectorate stage, and the opportunities for racialized women remain stagnant. Moreover, although white women experience a slight bump in representation at the candidate level, racialized women do not. Racialized men come forward as political aspirants in numbers that exceed their share of the population by 9 percentage points, but they lose ground at each successive stage. White men, by contrast, gain ground at each stage of legislative recruitment. White men make up 29% of the population, but their presence among legislators is 49%—that is a 69% increase! Racialized men enjoy a slight bump in representation between the eligible and legislator pools, but it amounts to an increase of just 11%, or 2 percentage points. White women’s presence decreases by 35% from the eligible to legislator stage, compared to a 50% decrease for racialized women.

Rates of Success

Another way of assessing race and gender in legislative recruitment is to compare success rates at key selection points (Freidenvall Reference Freidenvall2016). Standardizing the measure by looking at rates of success smooths out differences driven by variations in group size. To calculate the success rate for a group at the aspirant level, the number of successfully selected aspirants is divided by the total number who came forward. This calculation is repeated for each group at the next step of the legislative process, when candidates seek election as legislators. The results are shown in Table 1. The table also compares the relative success of groups.

Table 1. Success rates at each (s)election stage, by race and gender

Note: The column for relative success rate compares racialized to white, women to men, racialized women to white women, and racialized men to white men. It is calculated by dividing the success rate for groupA by the success rate for groupB. A relative success rate of 1 means the two groups had equivalent rates of success.

Consistent with the analysis of relative share, white women’s rate of success outpaces that of other groups at the aspirant-candidate stage when party selectors are making their choice, but it decreases in the candidate-legislator stage when voters decide. White aspirants have higher rates of success than their racialized competitors at both stages. Racialized women and men are equally successful at the aspirant-candidate stage, although racialized women gain a slight edge over racialized men at the candidate-legislator stage. Racialized women have lower success rates than white women at the aspirant-candidate stage when party selectors are choosing, but the pattern reverses at the candidate-legislator stage. Although racialized women are not as successful as white men in the final stage of legislative recruitment—the general election—they outpace other groups, a finding that should give parties additional confidence about their electoral potential.

Descriptive Over- or Underrepresentation

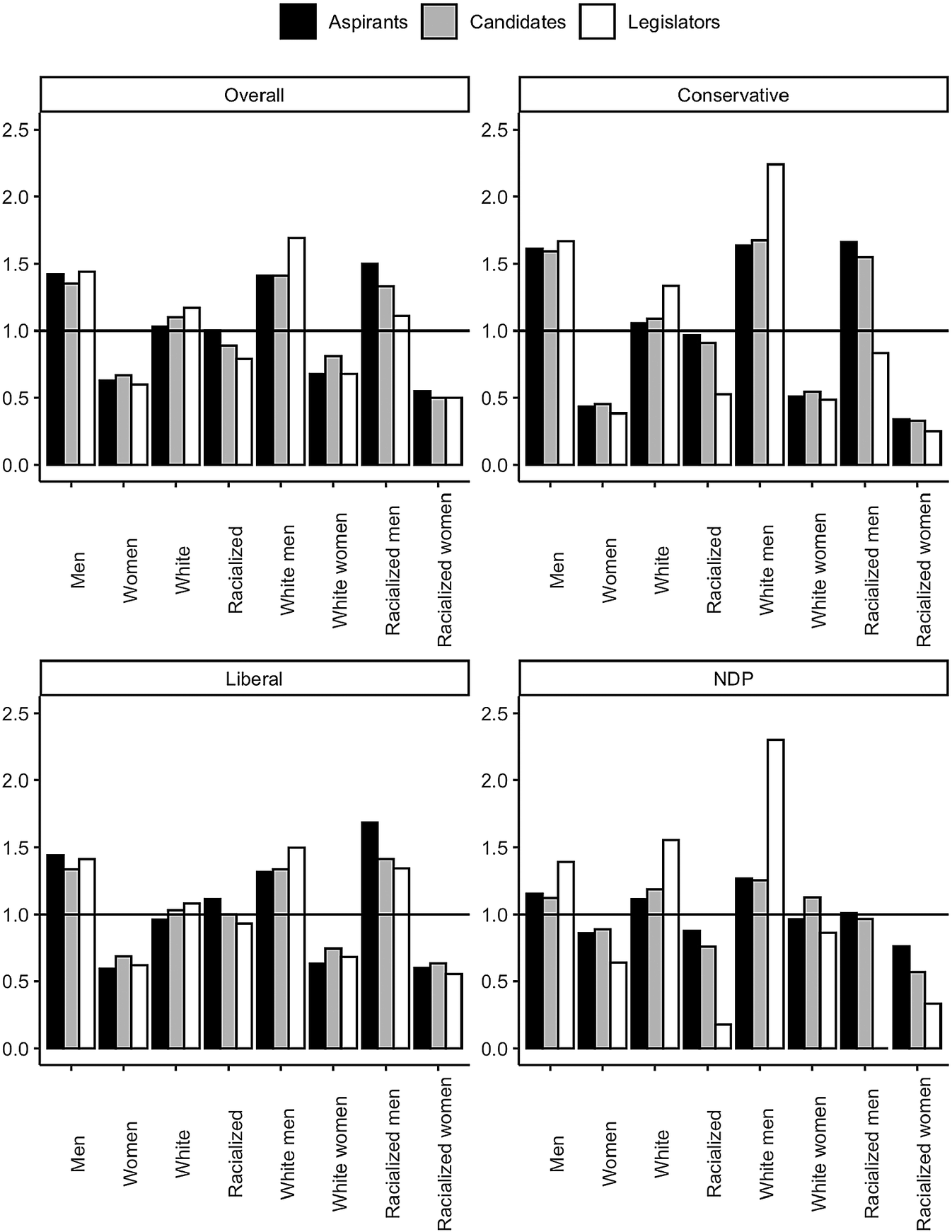

A final way to think about representational equality is to compare the presence of men, women, white, and racialized Canadians to their presence in the population (Clark Reference Clark2019). This measure illustrates a group’s descriptive over- or underrepresentation at each stage of legislative recruitment. A representation ratio of 1 indicates perfect proportionality: that is, a group’s descriptive representation at that stage of legislative recruitment exactly mirrors their presence in the population. As is shown in Figure 3, Canadians who are white and male are overrepresented at each stage of legislative recruitment, with representation ratios that exceed 1. Racialized men are also overrepresented, but the extent of this overrepresentation declines at each stage. This finding suggests racialized men have high levels of political ambition but are disadvantaged by lower levels of demand among party selectors and voters. The representation ratios for racialized women remain fairly stagnant across all stages, while white women’s representation ratio increases at the candidate stage, again suggesting party selectors may be playing a role.

Figure 3. Representation ratios at each stage of legislative recruitment, by gender, race, and party. Representation ratios for each stage of legislative recruitment are calculated as a proportion of a group’s presence in the population (see Footnote footnote 7). The horizontal line at 1.00 indicates proportionality

Figure 3 also includes the representation ratios by party. Although all parties are attentive—at least nominally—to the diversity of their candidate slates because they hope a wider tent will help broaden their appeal to voters, they differ in their commitment to affirmative action policies. In 2015, the NDP was the only federal party with an explicit affirmative action target, which proposed that candidates from historically underrepresented groups, including women and racialized minorities, make up at least 40% of the party’s slate. The Conservative Party typically adopts more of a free-market approach, encouraging a wide range of candidates to seek the nomination but not explicitly intervening to increase the number of women or racialized candidates. The Liberals, meanwhile, prefer a more middle-ground strategy. For example, through their “Ask Her” campaign in 2015, they encouraged the identification and proactive recruitment of promising women aspirants, but (unlike their commitment to a gender-equal cabinet), they did not set a specific candidate diversity target. Given these substantive differences in approach, it is somewhat surprising that the Conservatives and New Democrats do not vary much in the overrepresentation of white men on their candidate slates. The NDP’s track record with racialized women is also weaker than expected: it is below parity at each stage of the party’s legislative recruitment and dips noticeably when NDP selectors choose their candidate. This is not the case for white women, who are proportionately represented among NDP aspirants and experience a boost at the party selector stage. Although racialized men are proportionately represented on the NDP’s candidate slate, the party failed to elect even one. 9

Allocation of Open Seats

The preceding analysis demonstrates how race, gender, and intersectionality influence the relative share, rates of success, and proportionate presence of race and gender groups at each stage of legislative recruitment. Of course, these outcomes do not occur in a vacuum, but rather in a specific electoral context. In what remains, I discuss two features that may influence whether more diverse candidates come forward or are selected: first, the allocation of open seats, and second, the overall composition of candidate and aspirant slates.

Because the 2015 election followed a redistribution of electoral boundaries, there were new districts and many without any incumbents on the ballot. 10 When parties are not beholden to the sitting MP, they can nominate whomever they want. Theoretically, then, open electoral districts are an opportunity for parties to inject diversity into their slates. From the perspective of political newcomers, these districts are especially attractive since the advantages associated with incumbency, including electoral experience and name recognition, are absent, and all candidates can campaign on relatively equal footing (Kendall and Rekkas Reference Kendall and Rekkas2012). Whether parties opt to select women or racialized aspirants in these highly desirable districts provides some indication of their commitment to candidate diversity (Tremblay Reference Tremblay and Roth2010).

In the 136 districts included in this study, 43 had no incumbent running. All three parties selected a single candidate in these districts, so there were 129 nomination contests in which aspirants could come forward for an open seat. I look at the likelihood that an aspirant will emerge in an open seat rather than an incumbent-held seat, and I compare these proportions by race and gender. Data shown in the supplementary materials (Table S1a) reveal that nearly half of white aspirants (47%) emerge in open seats, compared to 35% of racialized aspirants. The gender gap is smaller, with 43% of female aspirants emerging in open seats compared to 42% of male aspirants. Given the comparative advantages of open seats, it is possible the competition for them is fiercer, and perhaps this deters racialized aspirants from coming forward. But why are women aspirants not similarly deterred? They are as likely as men to seek their party’s nomination in open districts, a finding that runs counter to the expectation that women would be turned off by a more competitive context. A more plausible explanation is that parties prioritize gender diversity over racial diversity and therefore more actively recruit women aspirants in these districts, provide organizational support to them, or discourage competitors from coming forward. 11 As a result, women aspirants are more likely than other aspirants to find themselves seeking their party’s nomination in a district where there is no incumbent.

At the point of selection, women also have an edge, with 46% of women aspirants ultimately being chosen as their party’s candidate across all open seats, compared to 37% of men. Among white and racialized aspirants, there is no difference; 41% are selected in open seats as their party’s candidate (see Table S1a). The absence of a racial gap on this measure suggests that while parties may not be openly discriminating against racialized aspirants who emerge in open seats, they certainly are not using these nominations to elevate racialized candidates. This is not the case for women, and particularly white women, who are more likely than any other group to emerge and be selected as candidates in open seats.

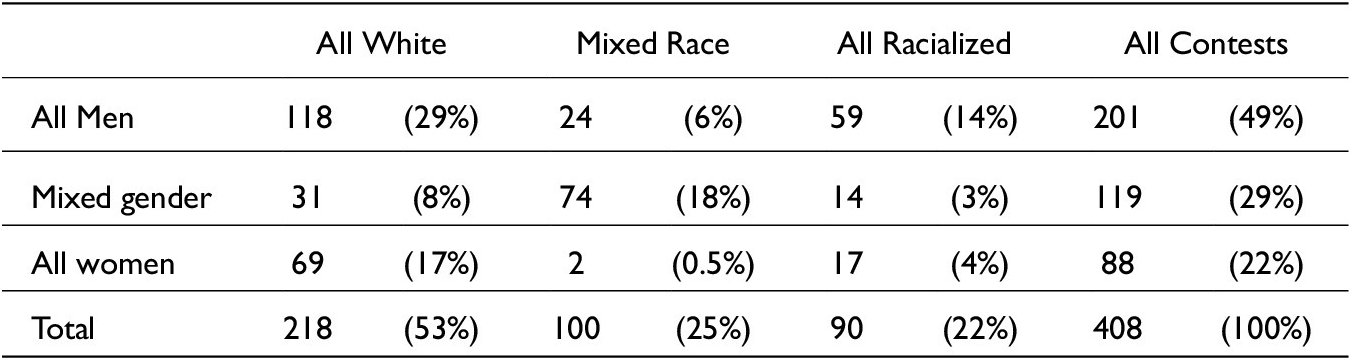

Overall Composition of the Slate

Finally, I consider the composition of nomination and election slates to understand the race and gender of competing aspirants and candidates. Looking at the 408 nomination contests in this analysis, what is perhaps most striking is how many include no women and no racialized Canadians (data shown in Table 2 in the entries for “All Men” and “All White”). This result is surprising because these nomination contests took place in diverse districts, in cities and metropolitan areas, and most with the features associated with upward mobility and less rigid gender roles, including higher levels of income and education. But even in districts where one would most expect to find diverse candidate slates, 29% of nomination contests do not have a single woman or racialized aspirant on the slate. More than half of all nomination contests (53%) include only white aspirants, and 49% have no women aspirants. Nearly one-quarter of nomination contests include only racialized or only women aspirants, but this is not the norm, and contests featuring only men or only white candidates are commonplace. This starting point influences each additional stage of legislative recruitment.

Table 2. Race and gender composition of nomination slates, by proportion of all nomination contests

Note: Percentages have been rounded and are calculated as a proportion of all nomination contests (n = 408).

Single-aspirant nominations are relatively frequent (54% of all nomination contests). These are, by definition, single-race and single-gender affairs. Single aspirants are about as common in all-white and all-racialized contests, but they are most common in all-women contests (see Figure S2 in the supplementary materials). Mixed-race nomination contests are larger on average than same-race contests, but there is little difference in the number of aspirants coming forward in all-white versus all-racialized contests. Moreover, although 70% of same-race contests have just one aspirant, this occurrence happens about as often in all-white and all-racialized contests.

In cases in which there are multiple competitors for a nomination, one consequence of all-white or all-racialized slates is that same-race aspirants square off against one another, but only one candidate can win. Intra-ethnic competition may thus be responsible for the successive decline in racialized competitors at each stage of legislative recruitment. I find that in all-white and all-racialized contests with two or more competitors, there is almost no difference in the number of aspirants coming forward (see Figure S2). Intra-ethnic competition is relatively rare, and it mostly occurs in nomination contests with two competitors. Just 10% of nomination contests with all-racialized slates had three or more competitors, which compares to 11% of nomination contests with all-white slates. The sheer frequency of all-white contests—more than double that of all-racialized contests—essentially washes away any effect, but it is notable that white aspirants are just as likely as racialized aspirants to engage in intra-ethnic competition. At the candidate stage, all-white slates again outnumber all-racialized slates. When voters in the 136 districts included in this study selected their legislator on Election Day, 50 districts had slates in which none of the candidates for the three major parties was racialized. Most districts (n = 73) had mixed-race slates on Election Day, and just 13 districts featured all-racialized slates. These data suggest that intra-ethnic competition is also not driving differences in representational outcomes at the legislator stage, not even in these diverse districts.

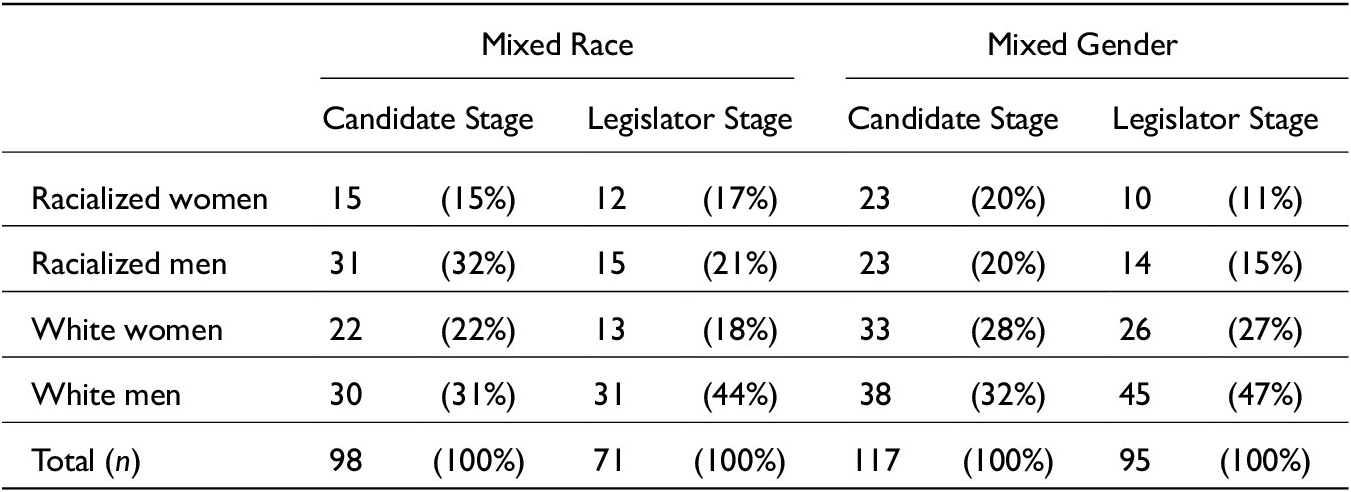

What happens when (s)electors are presented with mixed-race or mixed-gender slates? Table 3 shows the race and gender of candidates and legislators selected in those scenarios. When party selectors are presented with mixed-race slates, they choose racialized and white men in roughly equal numbers. When party selectors are presented with mixed-gender slates, they prefer white aspirants over racialized ones, and they more often select men than women. When electors in the district are presented with mixed-race or mixed-gender slates on Election Day, white men are preferred over all others. These findings suggest that even when (s)electors have the opportunity to choose diversity, they nonetheless gravitate toward those candidates and legislators who fit the traditional political archetype—namely, white men.

Table 3. Race and gender of winners in mixed-race and mixed-gender contests

Note: Two of the winners at the candidate and legislator stages are Indigenous, and they have been excluded from the totals for race.

Discussion and Conclusion

By focusing on the expansion and contraction of electoral prospects throughout legislative recruitment, this study illustrates the gendered and racialized dynamics that underpin each stage. Whether we rely on measures of relative share, rates of success, or proportionate presence to understand representational equality, the findings show that race and gender shape legislative recruitment in different ways. As a result, any elision of “women and minorities” will obscure substantive differences between and within these groups, while also concealing outcomes for racialized women and men whose own pathways converge and diverge.

Substantively, the findings show that candidate emergence is raced, gendered, and intersectional. Although racialized minorities are present in the aspirant pool, their presence declines at each stage of legislative recruitment. Strategies to increase political inclusion, therefore, should focus not only on women’s electoral prospects, but also on the racialized distribution of these electoral advantages (see also Krook and Nugent Reference Krook and Nugent2016). Racialized men come forward for party nomination in proportions that exceed their share of the population, suggesting that political ambition is not the barrier confronting these aspirants. Although racialized women are, like white women, underrepresented in the aspirant pool, the latter experience a boost at the point of candidate selection, while the former do not, suggesting that racialized women’s legislative recruitment is different from that of white women. Party selectorates seem more willing to choose white women as candidates, and parties’ efforts to diversify politics have therefore mostly benefited white women. Racialized women do not experience this same acceleration. These findings broadly confirm the laws of increasing disproportion (Putnam Reference Putnam1976), minority attrition (Taagepera Reference Taagepera, Rule and Zimmerman1994), and “the higher, the fewer” (Bashevkin Reference Bashevkin1985), although white women’s progression through legislative recruitment more closely resembles a diamond than a pyramid.

For all women, however, the initial entry point into politics is a hurdle. For white women, parties and party members help overcome women’s relative absence by selecting them as candidates in numbers that exceed their presence in the aspirant pool, but racialized women never recover from this initial blockage in the pipeline. Responses to address electoral underrepresentation should look more closely at the power party selectors and voters have and how their preferences determine the racial diversity of candidate and legislator slates.

Importantly, women’s relative absence in the candidate pool is not evidence that they are simply choosing not to participate. In some cases, women opt out of politics or delay their entry, but those choices are made in the context of an electoral arena that often appears ambivalent or even hostile toward women’s presence. It is only in the past decade that legislatures have begun to seriously discuss how to accommodate politicians who are new parents, including provisions for maternity leave and the relaxing of parliamentary rules to permit the nursing of infants in the House of Commons. Women politicians talk openly about the sexism they face, and a number of MPs have been removed from their parties’ caucuses because of sexual misconduct (Collier and Raney Reference Collier and Raney2018). The decision not to enter politics is made in this context, and that context includes an environment not as open to women as to men.

For racialized minorities, the context is somewhat different, but the roots are similar. Just as the electoral arena is a male-dominated space, it is also a space steeped in Eurocentric cultural norms. The foundations of Canadian democracy privileged white, upper-class men, explicitly excluding Indigenous peoples and racialized Canadians. Although those explicit exclusions have now been removed, it is not difficult to understand how a historical ethos of exclusion leaks into the present day (Bouchard Reference Bouchard2021). It is in this context that racialized Canadians are emerging as candidates. In doing so, they are forced to convince party selectors and voters they deserve to be there, that they will be assets not albatrosses. Even in the most racially diverse districts that are the focus here, it is clear such appeals have often gone unrealized. Public pressure to diversify politics or incentives to encourage it may help overcome the impulse to choose archetypal white candidates, but thus far, most initiatives aimed at improving electoral representation in Canada have targeted gender not race.

For women at the intersection, there is little evidence of a complementarity advantage; racialized women fare more poorly than white women at each stage of legislative recruitment, and it does not appear party selectorates are particularly keen to choose them. Although research in some contexts suggests that party elites maintain white male power in politics by strategically choosing racialized women over racialized men (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2013; Celis et al. Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damstra2014), in Canada, it appears parties often opt for neither. At the same time, the gender imbalance among racialized candidates suggests that the patterns that influence women’s overall representation are also present in minority communities. Research on South Asian candidates in Britain attributes men’s overrepresentation to “clan politics” and misogynistic practices within the candidates’ own communities (Akhtar and Peace Reference Akhtar and Peace2019). Intracommunity misogyny might dissuade racialized women from coming forward and thus hamper their political aspirations. Even if they forge ahead, such dynamics are likely to depress racialized women’s electoral successes because of a lack of support from their own communities, particularly in districts where co-ethnic selectors form a plurality. Not only would limited community support reduce their chances of winning the nomination in the district, it is also likely to taint party elites’ impressions of racialized women’s electability. In these cases, racialized women might be viewed as double liabilities.

The recruitment model employed here encourages an understanding of the political pipeline as a series of discrete stages. Although the framework helps to conceptualize legislative recruitment, it obfuscates how the initial decision to run is shaped by candidates’ assessments of the challenges they anticipate they will face in the electoral arena (Carroll and Sanbonmatsu Reference Carroll and Sanbonmatsu2013; Wylie Reference Wylie2020). For racialized women, these anticipated challenges are amplified by resistance to their candidacies from party selectors (and sometimes their own communities), the absence of role models, and raced and gendered institutions that have often been hostile to them (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003). As Dittmar (Reference Dittmar2015, 761) points out, “Incentivizing women requires more than asking them to run.”

In theorizing the politics of presence, parties are often conceptualized as gatekeepers to representation (Jensenius Reference Jensenius2016; Mügge Reference Mügge2016; Tolley Reference Tolley2019; Van Trappen Reference Van Trappen2021; Van Trappen, Vandeleene, and Wauters Reference Van Trappen, Vandeleene and Wauters2021). To some extent, the data bear this out, but not for all groups. For white women, parties emerge as facilitators; this group experiences a bump in their proportionate presence at the candidate stage, and they are also more likely to be selected in electorally advantageous open seats. Perhaps because of pressure to diversify their candidate slates, party selectors may opt to propel certain aspirants to victory or at the very least smooth the path, a process that Albaugh (Reference Albaugh2019) refers to as “affirmative gatekeeping.” These impulses appear to extend less often to racialized women or racialized men whose presence drops at the party selector stage. Future research should investigate these patterns to understand how party selectors’ demand-side considerations are shaped by ideology, policy, and practice. Preliminary analysis of legislative recruitment in the NDP suggests that on their own, a leftist orientation and explicit affirmative action policy are not sufficient conditions for increased descriptive representation.

The conclusions presented here are consistent with research on “acceptable difference,” which suggests when party selectors choose candidates, they gravitate to those who most closely fit their archetype of an ideal candidate. However, in Canada, as elsewhere, “there is a hierarchy of inequalities in which gender appears to be a much more accepted social category for inclusion in candidate selection than other categories” (Freidenvall Reference Freidenvall2016, 360). When pressured to expand beyond the usual archetype, selectors will do so by choosing a candidate who is the least threatening to the status quo (Durose et al. Reference Durose, Richardson, Combs, Eason and Gains2013). As a result, white women emerge as a primary beneficiary of parties’ diversification efforts. Analyses that center gender or rely on a universal woman to understand political experiences therefore ignore the racialized and gendered pathways trod by other candidates. The patterns documented here likely also reflect the close, homophilous networks that underpin candidate recruitment, and party elites’ own assumptions about the districts in which candidates can win, as well as the ways in which both shape individual choices (Cheng and Tavits Reference Cheng and Tavits2011; Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Oskarsson and Vernby2015; Ocampo Reference Ocampo2018; Thomas and Bodet Reference Thomas and Bodet2013; Tolley Reference Tolley2019).

Given the central role of parties in shaping descriptive representation at the aspirant-candidate stage, this is a fruitful space for future inquiry. Researchers may want to explore explanations for the patterns documented here, which could include causal approaches to untangle the effects of contextual factors, including party affiliation, competitiveness, and district demographics. Qualitative work could focus on party selectors’ motivations and might help unpack the considerations that underpin the selection of candidates, particularly in diverse or intersectional contexts. Researchers should work to collect pre-candidate data, in addition to data at the other stages of legislative recruitment. Buy-in from parties to obtain these data directly from candidates might help overcome the reliance on ascription and could also facilitate the use of more fine-grained racial categories. More complete data would also allow for an expansion of the analysis beyond the current study’s focus on the most diverse districts and for an exploration of dynamics in a broader range of contexts. These extensions would help address some of the limitations of the research design employed here.

Finally, it is noteworthy that gendered and racialized barriers to representation are present in a country like Canada, which has made explicit legislative commitments to multiculturalism and to gender and racial equality. Even when there is a normative stance that is favorable to inclusion, equitable political representation has not been realized. These findings do not bode well for countries that are less hospitable to diversity. More promisingly, however, they suggest that while parties are one of the most significant hurdles to political representation, they also have the capacity to facilitate inclusion. The case of white women in Canada illustrates this plainly. Party selectors have helped elevate white women to elected office through proactive, targeted recruitment and selection at the aspirant stage. They can apply these same measures to address representational deficits for other historically marginalized groups. Intersectional analysis helps to untangle the discrete, overlapping, and analogous effects of race and gender and will sharpen our understanding of political processes, institutions, and outcomes across a range of contexts.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X22000149

Acknowledgments

Reem Ayad, Ryan Atkinson, Anna Johnson, Rupinder Liddar, and Erica Rayment provided excellent research assistance; Alexandre Fortier-Chouinard aided with the production of the figures. The journal’s editor and two anonymous reviewers offered constructive feedback that helped improve the work, as did comments from an earlier round of revision at another journal. This manuscript has had a longer lifespan than I care to admit, and I have received advice from more colleagues and discussants than I can name individually. You know who you are, and I appreciate all of you. Funding from a University of Toronto Connaught New Researcher Award and the Canada Research Chairs Program is gratefully acknowledged.