In the musical history of the United States, “Hispanics” have traditionally been associated with popular music. However, this is only one segment of their contribution, and although U.S. art music historiography has given more attention to the European émigrés when it considers composers born outside the country, composer Aurelio de la Vega (b. 1925) shows that inside the American continent's art music flows “a fascinating series of influences, consequences, interactions, stylistic developments, passionate searches for identity, and slow growth toward esthetic and technical maturity,” and “the Latin American composers in the United States are certainly and decisively contributing to this fascinating process.”Footnote 1 A representative example of the previous statement is Max Lifchitz (Mexico, 1948), who has displayed a poly-artistic persona as a composer, pedagogue, conductor, performer, and cultural entrepreneur based in the United States. During an interview in 2005, the composer, when asked to define his eclectic style, expressed that doing so is a difficult task because of the probability of not being objective with himself; nevertheless, with some hesitation, Lifchitz articulated, “I think my style fits perfectly into post-modernism.”Footnote 2 Although the current article dialogues with this notion, it seeks to illustrate aspects of transmodernism in Lifchitz's holistic approach to music. Accordingly, Lifchitz, who operates in New York City—a city that has played a crucial role in defining twentieth-century Western art music modernism—displays a transmodern difference that transcends the predominant Euro-American postmodernism.

Postmodern and transmodern are philosophical concepts used by Argentinean/Mexican philosopher Enrique Dussel. With the aim of constructing a worldly and inclusive conceptualization of modernity, rather than the provincial European one, Dussel previously applied the term postmodern.Footnote 3 In his book Philosophy of Liberation (1977), Dussel wrote: “Philosophy of liberation is [a] postmodern, popular (of the people, with the people), profeminine philosophy.”Footnote 4 Thus, Dussel presented the term postmodern before the later publications by his Euro-American contemporary colleagues.Footnote 5 However, Dussel, who identified himself with the term postmodern about five decades ago, soon realized that postmodernity morphed into the critique of modernity from a Eurocentric perspective.Footnote 6 Thereby, he quickly diverted from it and began constructing his transmodern philosophy, which he defines as a liberation project of “mutual creative fertilization,” in an exterior space of solidarity that lay beyond (not after) the border of Western modernity (postmodernity), which he calls analectic.Footnote 7 In other words, analectic represents the incorporative solidarity between the traditional modern binaries “center/periphery, man/woman, different races, different ethnic groups, different classes, civilization/nature, Western culture/Third World cultures, et cetera.”Footnote 8 In his words, the philosopher explains further:

I have called “transmodernity,” a worldwide ethical liberation project in which alterity, which was part and parcel of modernity, would be able to fulfill itself. The fulfillment of modernity has nothing to do with a shift from the potentialities of modernity to the actuality of European modernity. Indeed, the fulfillment of modernity would be a transcendental shift where modernity and its denied alterity, its victims, would mutually fulfill each other in a creative process.Footnote 9

Dussel's proposal, which lacks any fundamentalist or anti-Occidental intention, seeks to generate an analogical and transversal intercultural dialogue between the allegedly multiple “peripheries” inside the analectic space. This space would be beyond the borders of modernity, including Western modernity.Footnote 10 Such an intercultural dialogue would therefore use the principle of analogy, a dimension of communication that achieves similarity by allowing respect for the “other” with the intention “to overcome the univocal character of modern Eurocentrism.”Footnote 11

Therefore, transmodernism opens a path for a pluriversal knowledge apart from Eurocentric “universality” to decenter this notion and share different epistemological creations. Nelson Maldonado Torres defines Dussel's transmodern philosophy as an “ethical recognition of the other as a subject of knowledge and culture.”Footnote 12 Dussel proposed a complete project of decolonization from the position of what Walter D. Mignolo defines as the knowledge produced from colonial difference.Footnote 13 Latin American, Latinx, and Chicanx philosophers have been revisiting and contesting Eurocentric philosophy as a result of experiencing the same epistemological marginalization.Footnote 14

After establishing briefly the historical and theoretical grounds to understand the necessity for the creation of transmodern philosophy and its relation to music, this article explores Lifchitz's early life in Mexico and then in the United States, a period that is of importance because it shows how his path begins to shape his multilayered transmodern approach to music. Although some will argue that his eclectic compositional style is postmodern, this article aims to demonstrate that, on closer examination, Lifchitz's overall approach to music and composition is transmodern. The article begins with a succinct historical introduction to modern art music across the American continent to understand the reasons behind the establishment of the North/South Consonance (1980) as a venue, and later as a record label (1992), in which concert and recording programs represent an intercultural sonic space with a firm anti-canonical political statement. Historically speaking, demographic changes have always impacted the creation of knowledge. Ultimately, what is at stake here is the consolidation of an intercultural epistemological approach as a way to make real the principles of equity and inclusion beyond a superficial multiculturalism. I argue that the organization engages with a repertoire produced by a varied and eclectic group of neglected composers. Accordingly, I also examine Lifchitz's approach toward recontextualizing music within education, another aspect of his transmodern approach. Thus, the article's goal is to demonstrate how the transmodern theoretical perspective is valuable to explain some of Max Lifchitz's multifaceted musical and cultural contributions.

Modernity, Transmodernism, and Western Art Music

Modernity, which materialized formally in 1492 with the reciprocal encounter between Europe and America, impacted humankind's history with its global expansion, including the circulation of ideas, goods, and people in all directions.Footnote 15 Before the Renaissance, Europe was peripheral to the Islamic world, Hindustan, Southeast Asia, and China. However, during the sixteenth century, the opportunity to relocate the geopolitical “center” from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic region allowed Europe, particularly Spain and Portugal, to create the first world-system, or the “first modernity.”Footnote 16 This turning point is also what Walter D. Mignolo (b. 1941) calls the “first global design of the modern/colonial world.”Footnote 17 The current discourse of modernity was born when Europe, once emancipated as periphery, became capable of constituting as the Self from an Other. Fernando Coronil (1944–2011) contends that “the Spanish and Portuguese colonization of the Americas made it possible to think for the first time in global terms and to represent Europe as the center of the world.”Footnote 18 Unlike Africa and Asia, America was considered an extension of Europe; a space where the Atlantic system and the genesis of capitalism, coupled with the expansion of Christianity, had initiated a process that Fernando Coronil described as “a process/discourse of Westernization or Occidentalization.”Footnote 19 With America, according to Aníbal Quijano (1930–2018), an entire universe of new material relations and intersubjectivities was initiated “between individuals and the peoples integrated into the new world-system and its specific model of global power.”Footnote 20 Arturo Uslar Pietri (1906–2001) argues that the American continent similarly transformed European cosmology, cartography, sciences, philosophy, and culture and generated a global vision of the planet that broke with mercantilism and the feudal city-states and progressively enabled the rise of capitalism and nation states.Footnote 21

Regarding music during this first phase of modern expansion, Western art music arrived on the American continent with the Spaniards, and to some extent the Portuguese, as part of their cultural arsenal to convert Indigenous people to Christianity (Catholicism). Thereby, Western art music became a tool to colonize (acculturate) the Indigenous communities and thus to construct and lead a vertical and asymmetrical intercultural relationship in Hispanic/Luso-American colonial society. However, the American continent's composers progressively integrated this musical tradition and have been transforming it according to their agency, culture, and history.

Since the Hispanic/Luso world's fall, the Central European world repositioned the Enlightenment as the genesis of modernity. The new designation of Spain and Portugal as second-rate powers raised the stigmatization of the cultural products produced both before and after by them and their former colonies. In music, Western art music historiography, as Judith Etzion clarifies, has halted “the history of Spanish music after its so-called ‘Golden Age’ of the sixteenth century,” as a result of the positioning of Spain in the Western periphery, and whose anachronism was due to the ‘Black Legend.’Footnote 22 Therefore Spain, and by extension Hispanic America, were treated by composers and musicologists as a highly exoticized and anti-modernity object and area during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This argument partly explains why Latin American art music, for instance, despite its more than 500 years of history, remains ghettoized as a musical/cultural/epistemological category, as Lifchitz's colleague, Venezuelan/U.S. American composer Ricardo Lorenz (b. 1961), points out, because of “assumptions that constrain Latin America's art music to the fringes of a historically and culturally ‘authentic’ Western art music.”Footnote 23 Therefore, following the fall of the era of Luso-Spanish global imperial dominance, the Reformation (1517–1648), the Enlightenment and its encyclopedism (ca. 1715–89), and the French Revolution (1789–99) arose and retained the same topoi about the American continent reproduced by the historiography of different European intellectual (scientific and artistic) disciplines.Footnote 24 Enlightenment philosophers from Germany, France, and England have been, since then, constructing a narrative to position them as the Self in terms of knowledge production.Footnote 25 Quijano explains that Europe, representing Western culture, positioned itself in a new geocultural role, although “Modernity is a phenomenon of all cultures, not just of Europe or the West.”Footnote 26 In addition, the structure of modern power became sustained by the theorizing of race as a category to construct epistemological hierarchies, which also applies to its (art) music.Footnote 27

Regarding music, Philip V. Bohlman, who argues for the (transmodern) pluralism of musics, explains that “the traditions of Western art music were content with a singular canon—any singular canon that took a European-American concert tradition as a given—they were excluding musics, peoples, and cultures.”Footnote 28 Accordingly, he explains that the disciplinary performance of the canon “covers up the racism, colonialism, and sexism that underline many of the singular canons of the West, and the canonic “authority” generates a dynamic of exclusion/inclusion that the scholar defined “not so much by what it was as by what it was not.”Footnote 29 This statement is connected to how modernism developed in the West and its relation to its art music tradition.

Max Lifchitz: His Years in Mexico and the Early Years in the United States

Max Lifchitz was born in Mexico City on November 11, 1948 into a family of Russian-Jewish émigrés.Footnote 30 The youngest of five siblings, he began taking piano lessons with a private teacher and then with the eminent pianist, piano pedagogue, and musicologist Pablo Castellanos Cámara (1917–81).Footnote 31 During this time Lifchitz also began composing music and wrote his Cinco Preludios for piano as well as his Trío para instrumentos de cuerdas (Trio for String Instruments), while taking lessons from the Spanish composer Rodolfo Halffter (1900–88) at the National Conservatory of Mexico. Spanish émigré composers and musicologists arrived in Mexico and other Latin American countries in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), and promoted a geocultural agenda known as Pan-Hispanism via neoclassicism, which in the field of art music regarded Manuel de Falla (1876–1946) as its highest model. Pan-Hispanism not only opposed both the Latin-Americanism promoted by France and the Pan-Americanism promoted by the United States, but also represented itself as the path to achieving the Eurocentric musical notion of “universality.”

In Latin America, musical modern aesthetics and techniques such as neoclassicism, dodecaphony, and serialism circulated across the continent, but similarly there was a twentieth-century musical modern Americanist trend created by a younger generation of composers that contributed to musical modernism. In post-revolutionary Mexico, for example, Carlos Chávez (1899–1978) used music as a medium for social and political transformation. Chávez became a crucial agent of change by decentering Germanic and Italian romanticism as hegemonic models in Mexican art music and, simultaneously, constructing a mestizo twentieth-century Mexican musical identity. It is also important to clarify that a quantitative measure of the degrees of Europeanism in Mexico and Latin America vis-à-vis the United States would be equal in sustaining culture as a fixed category, and European music is neither an authentic nor a pure category but the result of many cultural encounters in time and space. Thereby, qualitatively speaking, it is important to explain that cultural/musical encounters from Latin American constantly flow because of identity and internal/external aesthetical negotiations, as well as dialogues from composers and artists across the globe.

With the Cold War (1947–91) international milieu, for instance, several political, cultural, and even demographic reasons explain the fact that in Mexico, as clarified by Gerard Béhague, “Strict twelve-tone composition has not attracted the attention of young Mexican composers. Atonality and serialism (i.e., the serialization of more than one parameter) have found more acceptance.”Footnote 32 Argentinian/Uruguayan composer, Graciela Paraskevaídis (1940–2017), similarly clarifies the misconception that twelve-tone and serialist music in Latin America were thoughtlessly integrated by the younger composers in the 1930s and 1940s, stating that they were rather adapted to their aesthetical and ideological needs. In Latin America, twelve-tone music and serialism represented a modernization of language and a political posture against academicism. Paraskevaídis explains with great precision that while in Europe both were censored by fascist regimes as “degenerate art” and widely unknown between 1933 and 1945 (before Darmstadt), in Latin America (Argentina and Brazil) works of twelve-tone and serialist music were publicly performed and discussed.Footnote 33 At the same time, scores by Latin American modern composers circulated across the continent (e.g., Alberto Ginastera [Argentina, 1916–83], Antonio Lauro [Venezuela, 1917–86], Camargo Guarnieri [Brazil, 1907–93], Silvestre Revueltas [Mexico, 1899–1940], Carlos Guastavino [Argentina, 1912–2000], Julián Orbón [Cuba, 1925–91], Juan Orrego Salas [Chile, 1919–2019], Alejandro García Caturla [Cuba, 1906–40], just to name a few), creating a South–South dialogue among them that decentered Europe as the sole source for Western modern music.Footnote 34 In sum, the imaginary of Latin American music as a heterogeneous and transnational category, as Pablo Palomino explains, was formed by different actors that generated a regional space and created new musical products.Footnote 35

In 1966, having recently enrolled at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México to study philosophy, Lifchitz visited his brother in the United States. Travel can signify a ritual for change, and the young composer happened to meet Vincent Persichetti (1915–87) in Philadelphia. This meeting was a turning point on his musical path, as he recalls:

Persichetti was very kind and asked to see my music. I showed him the score of Trío para instrumentos de cuerdas [Trio for String Instruments]. He looked at it and then sat down at the piano and played from memory … I was so impressed that I said, “this is a real musician and I want to be like him!”Footnote 36

Thus, Lifchitz applied in 1966 to the Juilliard School of Music in New York City to study composition and was awarded a scholarship to attend. Although this was an honorable achievement it is important to acknowledge that it was in Mexico that Lifchitz gained his foundation of musical and cultural knowledge, which enabled him to further develop as a musician in the United States.Footnote 37 As an intersectional haven of divergent cultures, artistic events, and institutions, New York City became a significant venue for constructing identities, engaging in intercultural dialogue, and displaying the works of Latin American and Latinx composers throughout the twentieth century, who profited from the city's cultural capital. Marc Gidal indicates that this artistic and cultural migration to Western metropolitan centers created some challenges, because Latin American and Latinx composers had to become fluent in cosmopolitanism to navigate and negotiate the Eurocentric art music circles’ discourses of “multiculturalism” and “universalism.”Footnote 38 Although the music scene projects an image of inclusion, in reality it retains systemic privilege for the Euro-American canon. Consequently, Latin American and Latinx composers must construct polysemic adaptations to be able to navigate the Western art music tradition.

Latin American and Latinx composers are two heterogeneous musical/cultural categories from the twentieth century due to historical, political, and demographic changes in the Western Hemisphere. Both groups share similar cultural and ethnic roots and, at the same time, they both have to face cultural obstacles such as Euro-American power structures. On the one hand, art music in Latin America encompasses a history of more than 500 years, which shows a progressive appropriation and transformation of this music tradition according to their culture and history. On the other, the American continent's political dynamics during the twentieth century produced migrations into the United States, especially from the Caribbean, including Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Puerto Rico, and Central America. Furthermore, these populations settled mainly in metropolises such as Miami, Los Angeles, and New York City. Their musical cultures and identities blended with those from the United States, and a newer category of music and musicians appeared. Although members of both groups primarily belong to popular music scenes, some Latinx musicians embraced a Western art music tradition through U.S. mediation. Latinx composers are descendants of Latin American émigrés, born and musically trained in the United States. In fact, Ricardo Lorenz, who is a colleague of Lifchitz in the United States, expresses that Latin American and Latinx art music composers must deal with cultural and epistemological obstacles. Among them are the Western art music canon's construction of a racial and cultural division of the “Self” and “Others,” the global music industry's imposition of marketing tastes and distribution channels, and the representation of Latin American art music works and composers as exotic or byproducts.Footnote 39

Beginning in 1966, Lifchitz studied with the Italian composer Luciano Berio (1925–2003) and also received instruction from Vincent Persichetti and Roger Sessions (1896–1985) at the Juilliard School of Music. Lifchitz commented that Berio, unlike Persichetti, was not a natural pedagogue, adding that “he did not like to teach…he hated it.” Instead, he focused on his compositions. However, Berio invited him to work for him in Italy, and one of Lifchitz's assignments there was to analyze art music by European composers from different time frames, such as Guillaume Machaut (1300–1377) and Josquin Desprez (ca. 1440/55–1521), and find common elements in their styles. According to Lifchitz, “Berio used this material for the composition of the third movement of his work Sinfonia (1968–69).”Footnote 40 Later, Berio invited Lifchitz to move to France and work with him at the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique; ultimately, Lifchitz, who had a different calling, decided to stay in New York, “breaking off” with Berio to advance his own artistic persona.Footnote 41 In New York, Lifchitz received a scholarship to attend the doctoral program in composition at Harvard University, where he recalls that his experience with composers Leon Kirchner (1919–2009) and Earl Kim (1920–98) was simply a “disaster and I did not learn anything.”Footnote 42 After being named a Junior Fellow to the Michigan Society of Fellows, he then left for the University of Michigan to work as a composer for 3 years. Furthermore, U.S. music festivals served as venues where Lifchitz gained experience and presented his works. During summers at the Aspen Music Festival and School (1967 and 1968) he studied with Darius Milhaud (1892–1974), and he did the same in the summer of 1972 with Bruno Maderna (1920–73) at the Tanglewood Music Center. Curiously, both European composers had a connection to Latin American modern music history before meeting Lifchitz. Darius Milhaud lived in Brazil for a brief but intense and prolific period in his artistic life. Bruno Maderna went to Argentina to work as a visiting faculty in 1964 at the Latin American Center for Advanced Musical Studies (CLAEM) at the Torcuato di Tella Institute, where he taught the course “My Experiences in Electronic Music.”Footnote 43

Part of Lifchitz's engagement as a cultural broker in new music has been his role as facilitator in the classroom—where most of his students have been non-music majors—which he carries out in addition to his concerts and recording series with North/South Consonance, which for over 40 years has been active in the New York new music arena. Accordingly, after his time in Michigan, the composer returned to New York City, where he taught Counterpoint and Music Theory at the Manhattan School of Music for a brief period and, in 1977, he was hired as an Assistant Professor at Columbia University, where he taught a course about Latin American music—the first offered in that music department since the 1940s.

Later, the University at Albany, State University of New York, appointed him as Professor, and he has served there as Chair to the departments of Music and Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies. His academic positions have provided opportunities for Lifchitz to share and theorize about different music traditions, which aligns with the transmodern principle of interculturality. Lifchitz's life story is significant and helps clarify the reasons for his decision to develop his professional path differently, and to understand how a member of the Jewish diaspora circulates and interacts with various cultures and beliefs (e.g., Mestizo and Indigenous communities in Mexico, the Euro-American and Latinx in the United States, and the European). This quality made him aware and sensitive about different constructions and interpretations of modernity. Historically speaking, the dialectic between selfness and otherness generated by Western modernity has been a difficult milieu to deal with for the Jewish people and Jewish musicians, and music has represented a way to assert their identity within this complex dynamic.Footnote 44 It is not surprising that for Lifchitz transmodernism can offer a more harmonious philosophical path to manage and navigate this historical period. Transmodernity offered the unconscious conditions for liberation, allowing the composer to display his agency and develop his compositional and pedagogical voice. These reasons simultaneously relate to some of the ideals proposed by Dussel's transmodern theorizing, as I will demonstrate in subsequent sections.

Eclectic Musical Language

Max Lifchitz asserts that in the twentieth century composers enjoyed “complete freedom to cultivate highly personal style.” The composer reflects on his compositional style and summarizes it as “a syncretic amalgam of diverse trends and conventions.”Footnote 45 This philosophy allies with Dussel's transmodernity, because Lifchitz's agency allows him to reject the notion of what Dussel defines as Eurocentric modernity's “univocity of identity”; a “possession of the truth.”Footnote 46 Instead, Lifchitz's music represents the transmodern ideal of analogical dialogue, which can be described as an interaction with other musical cultures and periods of human existence within the frame of cultural similarity. Therefore, the process of analogical dialogue leads toward transmodern analogical pluriversality, in which the composer's musical language embraces distinct cultures while articulating the principle of similarity.Footnote 47 The works conceived with a hybrid knowledge do not fit the Western logos because of ethnocentric and epistemological hierarchies that generate their classification and reception as a subaltern knowledge. Accordingly, the dilemma of being forced to choose between nationalism and universalism is a commonly heard topos among Latin American and Latinx composers, whose works’ position within the Western art music tradition suffers from objectification. This binary division is typical within modern structuralism; therefore, transmodernism as a philosophical path can help Latin American and Latinx composers to find their compositional voices in their music works.Footnote 48 This is the reason why transmodernism helps to open a pluriverse where these musical works are not peripherals. For Dussel, the transmodern intellectual/artist subject is located in an area of critical thinking and creation (analectic space) beyond these two contrasting elements or cultures.Footnote 49 In other words, transmodernism supports the notion of eliminating geocultural epistemological determinism because it decolonizes the idea of universalism from the globalized coloniality and postulates a worldwide pluriverse with epistemic cultural emancipation.Footnote 50

As a transmodern composer, Lifchitz is not afraid of using a combination of folklore, classical forms, and avant-garde techniques.Footnote 51 For the composer, moreover, there is no modern barrier between the Eurocentric binary of so-called high and low culture, but the opposite; for him, music is a point of encounter between diversified cultures. “People will ask me if a musical phrase was an actual quote from a folk song or dance,” said the composer, “and I say, ‘No, but it is from very old-fashioned sounds, done with contemporary technique’… I am in other words very much an eclectic composer, and I'm not ashamed of that.”Footnote 52 Therefore, for Lifchitz as a transmodern composer, folklore does not represent backwardness or pre-modernity. Instead, folklore can dialogue with classical forms and avant-garde techniques without losing its cultural distinctiveness inside the analogy's logic, whose “fusion of horizons” permits their mutual understanding and distinction's respect within the composer's works.Footnote 53 Scholars, for instance, have recently contended that the discourses and definitions of “avant-garde” art or “experimentalism” reinforce an ontologically fixed and privileged Euro-American center. This political/cultural trend excluded Latin American composers, whose musical works, as an example, had already experimented with sounds and intervened in Western art music conventions.Footnote 54 Lifchitz approaches composition as an intercultural process and rejects the strict aesthetic limitations of genre, style, and period.

Lifchitz does not hesitate to borrow from old composition techniques or genres from previous music periods to compose his music, in this case, the Italian Renaissance. His intertextual approach reminds us of music's transtemporal quality. In his work Three Concerted Madrigals (2012), Lifchitz plays with the genre's style—for example, the interplay of homophonic and polyphonic sections or emotional word painting. This is another exercise in transmodernism because Lifchitz does not assume the postmodern posture of repudiating modernism, specifically what Philip Bohlman has described as its “conscious repudiation of the past.”Footnote 55 Thus, transmodernism is present when Lifchitz exercises his agency and decides to create a border musical knowledge between binaries, and, at the same time, his works do not repudiate either popular music or previous Western art music styles.

The work Yellow Ribbons no. 44 (2007) for flute and piano is part of a series dedicated “To All the Victims of Terrorism.” Lifchitz wrote an introduction to the work's history in the score.Footnote 56 The transmodern quality of the series is evidenced in a musically symbolic text that responds to the fundamentalist and complete negation of the pluriversal analogical character because of its political/cultural Manichaeism, which eliminates “the dialogue between distinct existent cultures which recognize the dignity of others, and also of modernity.” The Yellow Ribbons series, therefore, positions itself as a musical transmodern text between two excluding loci that Dussel defines as the “univocal European identity” and the “destruction of modernity.”Footnote 57 Namely, these series represent a group of musical texts against the fundamentalism that eliminates the legitimate human right to exercise responsible freedom of speech and agency, and their political message is contrary to the intellectual and artistic repression of totalitarian regimes and projects. For Lifchitz, these series represent a sonic symbol about the connection between the freedom of expression and creation, which have enabled, for instance, the use of the arts to encode and convey claims about rights.

The first movement begins with the work's thematic exposition by the flute within a monophonic texture. This texture symbolizes the hostage's solitude. Further, it presents, in a condensed form, the phrases and motives with a variety of rhythms, articulations, tempo markings, and dynamics using the first octatonic scale. Then the piano appears (rehearsal A) with a half-note dotted tetrachord, which descends and ascends symmetrically, and the composer permutates these chords with the augmentation and diminution procedure across the movement. The piano tetrachords function as a sound mass, which is reinforced with the pedal and establishes the beginning of an interplay (action–reaction) with the flute. This kind of aggressive interaction in combination with the symmetrical sound mass coming from the piano represents the anxiety of dealing with an uncertain liberation as well as the loss of freedom. Meanwhile, the flute plays descending, almost chromatic, lines while employing the flutter technique, which provides a particular performance practice timbre (like a tremolo), and this kind of segment appears in alternation with less active rhythmical sections.

The second movement is the longest and is introduced fortissimo by the piano in the first measure with tetrachords. From the second measure this texture breaks, exposing the beginning of an arpeggiated pattern of three (p) against an ostinato in two (mp). The flute joins the piano in this measure with disjunct melodic material. The composer generates a climactic intensity by combining these musical ideas with rhythmic diminution, strategically prepared rests, and more chromaticism. From rehearsal mark E the perception of speed and intensity increases with ascending and descending arpeggios combining to form an ostinato, which includes quintuplets, sextuplets, decuplets, and dodecuplets. The movement's climax arrives when the flute and the piano come together in a pointillistic segment in which the piano performs symmetrical ascending heptachord clusters, leading toward the flute's cadential section, which functions as a coda. The third movement embraces a similar idea and aesthetic as the first. In general, the three-movement work's macro form is A-B-A′, and it explores different tessituras and timbres.

Lifchitz has defined himself as an eclectic composer, and this self-representation includes the notion that, despite surface differences, the music of the pluriversal world shares polysemic similarities, whether in America, Africa, Europe, Asia, or elsewhere. This polysemic element is present in his work Confrontación (2006). Hence, in transmodern theory this polysemic difference, facilitated through intercultural dialogue, generates a mutual and similar, not identical, comprehension within the music work. In discussing the work's nature, he refers to its “confrontation and eventual reconciliation of opposing musical materials. … [T]he musical discourse juxtaposes and contrasts melodic and rhythmic gestures of various ethnic origins and historical eras,” which includes stile concertato throughout the work and the sublimation of several melodies: “Hanacpachap Cussicuinin” (Peru, ca. 1600), the Spanish Renaissance romance “Vos me matastes” (“You have slain me”), and the plaintive Libyan caravan song “Ajjamal Wanna.”Footnote 58 In this work the viola begins with a cadenza, using idiomatic resources (tremolo, pizzicato, chords) on a synthetic scale that suggests Asia/North Africa. During the subsequent movements, Lifchitz's narrative develops elements such as modality, tonality, and atonality, polyphonic and polyrhythm textures, and contrasting registers within the permanent interplay and dichotomy of conflict/resolution. Confrontación's transmodern conceptualization entails the pluriversal, transversal, and transtemporal dialogue between all these different cultures. As Dussel would argue, this dialogue is neither modern nor postmodern but transmodern, because the work's creative analectic union of opposites does not come from modernity's interior but from the “borders.”Footnote 59 This approach and process, to cite an instance, enables him to create contrasting aesthetical and sonic music works such as his series Yellow Ribbons, Rhythmic Soundscape, and Mosaico Latinoamericano (1991).

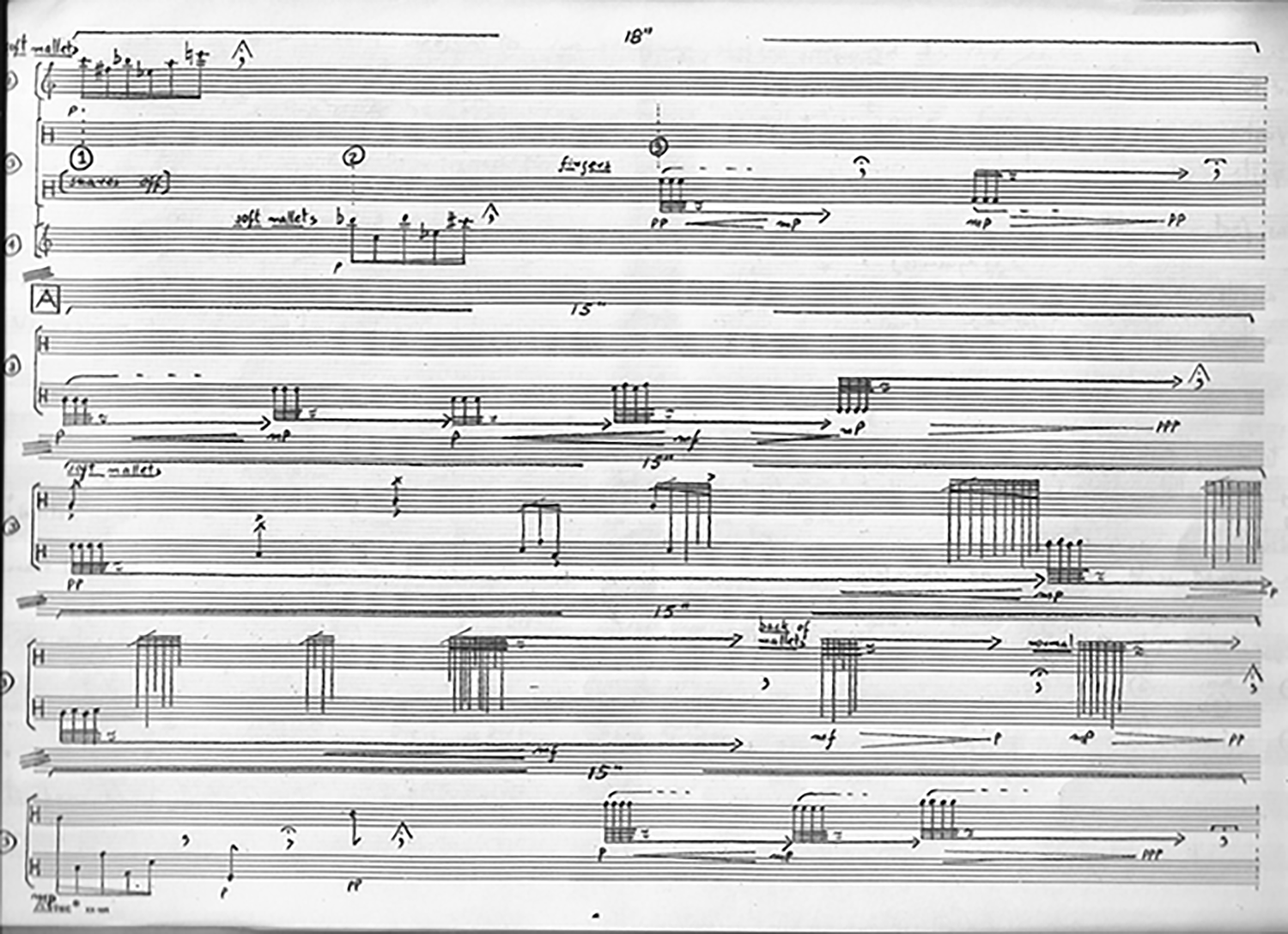

In Music for Percussion (1977, Figure 1), a work in three movements for five performers, Lifchitz explores the sounds of a group of over fifty percussion instruments. The transmodern philosophy is represented by the utilization of percussion instruments hailing from a multitude of different cultures, dialoguing throughout the work. The first movement, “Whispers” (performers 2, 3, and 4), creates its sound atmosphere by combining different musical elements. For instance, motives with dynamics centered on p and its variants (ppp, pp, mp) dominate most of the movement. The melodic design is pointillist, and it is based on the octatonic scale (0, 1) with added chromaticism. Additionally, the composer juxtaposes its motifs within cross-rhythms. The second movement, “Provocations” (performers 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5), begins with a voice (saying the vocables ketcho, kotcha, kutcha, and katchu) with a pointillistic rhythm, sometimes simultaneously, sometimes asynchronously. The movement then builds up the sonic intensity with ostinato and isorhythmic patterns of thirty-second and sixty-fourth notes on chromatic or octatonic scales, and the instruments’ inter-crossing generates a polyrhythmic climax. Lifchitz then decreases its tempo and density while augmenting the rhythm toward the end. The third movement, “Repercussions,” shares feature with its predecessors by using tempo modulations and polymeter. A general feature is a unique timbre that results from the combination of unpitched and pitched percussion instruments throughout the work.Footnote 60

Figure 1. “Music for Percussion” manuscript. Composer's personal collection, used with permission.

Lifchitz's personalization of his musical language also creates contrast with techniques such as expanding versus contracting intervals, the juxtaposition of metered versus non-metered sections, and the counterpoint of tempi or superimposing several tempi and contrasting sonorities in the orchestration. Regarding this approach, Lifchitz says that he is conscious of creating a shape and direction, something that atonal music often lacks because of the lack of tension between tonic and dominant. By using rhythms, motives, textures, and timbre, Lifchitz provides the necessary means for audiences to feel the direction of his music.Footnote 61

The North/South Consonance as a Transmodern Space for Music

In 1980, Lifchitz founded and became artistic director of North/South Consonance because “while there were many ensembles performing music by U.S. composers, there were no classical music ensembles regularly performing the music of composers from Latin America in New York City.”Footnote 62 Lifchitz says of his own experience, “Hardly anybody had heard composers from Latin America. So one of my ideas was to perform [the] music of Latin American composers; many of them were writing in a contemporary idiom, but nobody bothered to program them.”Footnote 63 Later, North/South Consonance became “a non-profit organization based in New York City devoted to the promotion and performance of music by composers from the American continent.” The ensemble expanded from being a space for a South–South compositional dialogue and exchange to fostering a North–South exchange as well.Footnote 64 Composer Hilary Tann articulates a clear image about her colleague and the ensemble when she explains, “The name says it all. North/South is not only North America/South America but also an acknowledgment that differences can be reconciled. Then the word ‘consonance’ brings us into a musical territory and the last thirty years of superior music-making.”Footnote 65

Lifchitz explains that one of his initial ideas for his organization was “not to segregate the composers … so they'd get to know each other, and the public too.”Footnote 66 This argument supports the performances of works by “underrepresented North American composers, including women and African-Americans.”Footnote 67 Furthermore, it represents a highly transmodern political position because the composer and North/South Consonance never took any side concerning the postmodern “aesthetic battles between ‘uptown’ intellectual music and ‘downtown’ experimentation [that] raged through the ’80s and the ’90s.”Footnote 68 Therefore, within the dynamics of the New York City new music scene, for instance, North/South Consonance self-identifies as an out-of-town platform—that is, a metaphorical way to promote the transmodern analectic space of cohesive cross-fertilization and welcome works created in the worldwide global pluriverse, beyond the uptown and downtown aesthetics of New York City. At the same time, works submitted from either of the two sides should not be excluded from the concerts. Joseph Dalton, furthermore, interprets this as a move by Lifchitz to remain “below the radar of musical politics and trends.”Footnote 69 However, Lifchitz's neutrality is a transmodern political position because it symbolizes the analectic space pluriversity. Hence, North/South Consonance has been demonstrated to be a holistic organization, whose programs, for instance, reflect a transmodern philosophy in their diversity of aesthetics.Footnote 70

In other words, this musical territory transforms North/South Consonance into a transmodern aural anti-canonical space to reframe the “global” network of new music contemporary composers. The idea is to transform the ensemble stage into a transmodern intercultural “contact zone” for multiple musical languages and identities within the world.Footnote 71 Thus, the reality of modern canonic formations impacts composers by narrowing the opportunities to share their music publicly in live or recorded performances. Since then, the spectrum of the organization's repertoire has continued expanding: The main objective is about performing “music by composers of our time … from every corner of the world.”Footnote 72 Although the organization's name has remained the same, its purpose and meaning has been transforming itself in time and space. Thereby, in recent decades the organization has become a space for an intercultural musical dialogue between composers, whose musical identities do not necessarily root them in a specific geographical register because their cultural uniqueness is in constant exchange with various cultures, soundscapes, and real or virtual locations. This is musical translocality as a transmodern practice of going beyond pre-established modern cultural and political borders.

The organization holds its call for scores every year to select compositions to feature in its concert series. Indeed, composers from across the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Africa submit works for performance consideration. Lifchitz confirmed that he has performed works by West, East, Southeast, and Pacific Asian and African composers with the North/South Consonance.Footnote 73 To illustrate, by examining a microcosmos sample, the programs include works such as Eun Young Lee's Mool (2012), Füsun Köksal's Dances of the Black Sea (2013), Niloufar Nourbaksh's Fixed (2017), Joyce Wai-Chung Tang's Aurora (2008), Mei-Fang Lin's Time Tracks (2001), Tonia Ko's Still Life Crumbles (2012), and Talia Amar's Morphing (2009).

As shown, the organization's focus is not only on reconceptualizing new music culture, but also on the lack of gender diversity within it, because of asymmetrical male/female participation (power), which reduces women's contributions and excludes their musical creations.Footnote 74 Gender similarly plays a role in the Western art music canon, whose traditionally male-dominated history directly impacts the performances and commissions of musical works by women composers.Footnote 75 In this context, North/South Consonance is a forum for intercultural communication for new music musicians and audiences. This political and organizational restructuring and vision was described as follows: “Lifchitz's agenda with his long-running North/South Consonance concerts is to cross-pollinate on a global level and promote the work of composers from across the American continent alongside their counterparts from literally everywhere.”Footnote 76 Thus, North/South Consonance exercises its political and cultural agency by promoting these composers’ music, and in so doing, the organization is also a way to interconnect and re-articulate their meanings and identities with audiences. In short, race, age, nationality, and gender, among other significant categories, play a role in redefining aural spaces, that similarly defines the organization's identity in the concert arena (see Figure 2), which could be summarized in the following statement about the organization's “advocacy efforts on behalf of music by living composers. North/South Consonance concerts and recordings consistently feature music by composers hailing from throughout the world and representing a wide spectrum of aesthetic views.”Footnote 77

Figure 2. Program of North/South Consonance Inc. Used with the permission of Max Lifchitz

Funding is also crucial to keeping transmodern spaces open to the public. Establishing and sustaining a new music ensemble is not an easy task, especially when larger and older orchestras, whose yearly programs include Western art music's canonical works to ensure a reliable and financially generous audience, are struggling to survive. Andrea Moore writes that in the United States no musical ensemble covers its costs only with ticket sales, and therefore, “they must rely on individual donations, foundation grants, corporate largesse, and, occasionally, government support at the local, regional, or federal level.”Footnote 78 Lifchitz speaks about his experience regarding the cultural and historical connections between funding and arts in the United States, where the state is absent and the responsibility to ensure financing depended on the artists’ entrepreneurial skills and, mostly, the private sector.Footnote 79 “Arts institutions in the United States,” argues Lifchitz, “function primarily through the generosity of private individuals. In general, official support does not exceed more than a third of the budget of any institution. Contrary to what is happening in France or Germany, the [U.S.] government does not want to have much to do with the arts. Out of ignorance, it is suspected that the arts are elitist or even undemocratic.”Footnote 80

The composer and the ensemble fall into the category of cultural entrepreneurs, which Andrea Moore defines as not only “those who introduce wealth-creating products or technologies, but also those who propose new forms of organization, uncover or create new markets, or develop new ways of working.”Footnote 81 Therefore, with the aim of promoting access to culture (not Culture), for instance, the concerts by North/South Consonance are free, because as Lifchitz explains, “We don't want the ticket price to be an issue in deciding to go to concerts.”Footnote 82

In 1992, North/South Consonance launched a record label that has released more than sixty CDs. The North/South Recordings label emphasizes an eclectic mix of musical aesthetics, compositional techniques, genres, and ethnicities.Footnote 83 Lifchitz expresses that the “organization also was established to become a recording forum for works by this neglected group of artists.” Audiences may assume that both are merely an outlet for new music. Although I agree with them up to a point, I still insist that with this career path, the North/South Consonance and Lifchitz joined the group of musicians in the United States who have occupied a position of musical leadership, and they have been contributing to the diversification of art music in the United States, whose primary narrative tends to leave any group different from the Euro-American on the outside. Thus, the organization's transmodern approach is about being a space for those composers whose music has been positioned as Other in the music programs of regular symphonic orchestras.Footnote 84 By presenting the new music of his colleagues, Lifchitz, already a well-established composer with many performances of his works, commissions, prizes, and a large catalog to his name, is showing his belief in the transmodern principle of solidarity.Footnote 85 Lifchitz could easily have concentrated only on promoting his own work, but his transmodern approach to music detached him from the traditional modern composer's ego. As a result, he invested his time, energy, and resources to create an analectic space where the distinct works of his colleagues could be performed and appreciated.Footnote 86

As a composer, Lifchitz believes that twenty-first-century composers must constantly reinvent themselves to reach audiences through their music. Despite the present resources for creation, finding an audience for new music has been challenging. Thus, Lifchitz asks a simple question: When will audiences follow?Footnote 87 Hence, he points out that contemporary obstacles such as the music industry, technology, and the lack of venues, performers, and institutional support for new music must be a motivational opportunity to transform this reality.Footnote 88 It requires artists to redefine the study of composition and accept that the current environment for living composers is not the same as that of the nineteenth century or earlier periods.Footnote 89 Ergo, Lifchitz had to deconstruct the historical role of the traditional composer and reconstruct a new one that reflects his versatile musical persona and articulates what composers must do to succeed.

Music, Equity, Inclusion, and Education

Beyond concert halls, classrooms are powerful spaces to engage new audiences with music and its connection to culture and society. The combination of education and music has enabled Lifchitz to interact with varied communities of students throughout his life. Consequently, he experiences how a permanently changing milieu challenges the role of music educators and composers alike. Within the modern era of globalization, in which technological speed means that changes occur faster than before, Lifchitz recognizes how non-musical transnational dynamics related to power, identity, tradition, and ethnicity, for instance, circulate globally and impact music and music-making, among other socio-cultural structures and webs. Accordingly, he acknowledges the impact of non-musical globalization dynamics in the classroom and, in general, how knowledge is now shared:

Rapid demographic and technological transformations are having a profound impact on existing political institutions throughout the land. These changes have strong implications for institutions of higher learning and are fueling the need to reexamine our roles as both pedagogues and practicing musicians.Footnote 90

Demographic changes, for instance, permanently leave their cultural footprints, as culture historian Adelaida Reyes articulates. She points out that, in the United States, diversity generates a cultural wealth for the nation and defines its musical life.Footnote 91 Reyes explains that the musical synergy within U.S. America society embraces:

Hybridity in all its forms and musical sources worldwide now flourishes in an environment where European immigration no longer dominates. An unprecedented number of musical hybrids have come into existence. They now seem poised to become the rule rather than the exception.Footnote 92

With this focus, Lifchitz works toward avoiding the construction, reproduction, and stigmatization of traditionally excluded ethnicities from higher education and, at the same time, deconstructing the structural paradigm of societies in which music and the music-making process have been displaced and deconceptualized. Therefore, in the field of music, Lifchitz proposes, “The study of musical concepts derived from European musical thinking should be balanced with exposure to aesthetic concepts underlying art from non-western cultures.”Footnote 93 This statement represents Lifchitz's transmodern educational approach, because it invites us to rethink educational institutions as spaces where the barriers that marginalize epistemic subjects can be deconstructed. This approach allies with Dussel's ideal of an “epistemological, cultural, and technological decolonization that has a distinct project (…) to advance towards another that ought to continue with the ontological, ethical, cultural traces of one's own traditions, which are alive, within a new future [transmodern] civilization.”Footnote 94 Furthermore, Lifchitz's proposal amounts to much more than a mere ethnomusicology class. First, all music, including the Western art of music, is an ethnic cultural product. Second, he seeks to create an analectic space in the classroom for an epistemic conversation among similar subjects that are not identical, because ontologically speaking that is impossible.

In recent years, this idea has been reiterated by scholars such as Phillip Ewell and Loren Kajikawa, who identify structural systemic elements that reproduce epistemological imbalances within the U.S. music school system and Western culture. Ewell points out that the conceptualization of music theory courses at the college level, with its current emphasis on Euro-American theorist and composers, is racialized.Footnote 95 Accordingly, race and epistemology intersect in music theory courses in higher education programs and significantly reduce it into a univocal area of knowledge that leaves behind various cultural music theories that can also benefit students. Ewell affirms that:

If we truly “embraced all approaches and perspectives,” then we would make them—the music theories of Asia, Africa, or the Americas—part of required music theory classes in our curricula, from freshman theory to doctoral comprehensive exams, and our undergraduate textbooks would not be based solely on the music of whites.Footnote 96

Loren Kajikawa also indicates that “possessive investment” in Western art music by schools of music and departments establishes a synergy to generate prestige and attract funding, but this dynamic simultaneously creates the dichotomy of inequality and privilege, depending on the racial and ethnic group, because these reproduce racial developmentalist and evolutionist tropes. Kajikawa explains that “U.S. music schools helped reinforce the supremacy of Euro-American culture by maintaining a strict separation between classical music and other genres considered to be less cultivated.”Footnote 97 Ewell and Kajikawa call for an intercultural and transmodern approach in which Western art music theory forms dialogues with different cultural music traditions and theories.

This position aligns all of them with transmodern philosophy, which promotes epistemological decolonization within social institutions such as universities. Ramón Grosfoguel explains that Dussel's transmodernity engages with an intercultural dialogue and exchange that, from a position of critical border thinking, aims to decolonize Eurocentric modernity and, at the same time, open the path for a pluriversal knowledge.Footnote 98 Therefore, Lifchitz joins the group of college faculty members who wish to participate in the dialogue between distinct epistemic horizons to generate pluriversalism and, by extension, an institutional pluriversity, which includes the “Others” as knowledge producer subjects.Footnote 99 In other words, the composer promotes the more inclusive pluriversalism and pluriversity, instead of the Eurocentric model and notion of universalism/university. Thereby, the composer, for example, also speaks out about embracing various rich musical cultures beyond the Western culture by avoiding the commercial label “world music.” Because old institutions such as colonialism have not yet disappeared but have adapted to the new times, the dominant culture (supported by its wealth and capacity to reproduce it) created the label “world music” as a form of coping and, according to Jocelyn Guilbault, used it as a mechanism to “reinforce their control and power over emerging sociopolitical, cultural, and economic destabilizing forces.” At the same time it “reproduce[s] with a different strategy the reinvention of the old connection center/periphery.”Footnote 100

Lifchitz aims to bring more diversity and equity, which he argues are “often overlooked by traditional academic and concert institutions,” as a path to enhance the students’ educational experience from the perspective of an insider who can engage and navigate different cultures with fluency.Footnote 101 This is a different ideal than that proposed by multiculturalism, in which the differences are erased under superficial rhetoric of ignoring power hierarchies (fictional sameness). Moreover, Lifchitz criticizes efforts to eliminate Affirmative Action because, without this law, he feels that communities will be deprived of their deserved educational opportunity. After all, discrimination promotes and reproduces systemic inequalities against groups traditionally excluded from the higher education system in the United States. Lifchitz indicates, “Affirmative Action has been legally abolished in some states forcing institutions of higher learning to adopt admission and recruiting policies completely divorced from previously accepted ethnic and gender considerations.”

Lifchitz concludes that “as teachers, administrators, composers, and performing artists, we have an obligation to reach out to all constituents of today's society.” Accordingly, for him, pluriversality increases educational and cultural capital because, “Diversity enriches the educational experience of all individuals. Student bodies and faculty who truly represent all segments of the entire population enhance the educational experience for all constituents of the academic environment.” In short, Lifchitz summarizes his pluriversal vision of education when he states, “We cannot escape the pressing exigency to make our artistic and teaching institutions truly reflective and inclusive of a diverse populace espousing a multitude of aesthetic viewpoints.”

At the same time, one of Lifchitz's educational and new music goals is to have active audiences who think, question, decode, and resist manipulation, especially by modern mass media or the status quo. This is the type of reception that Stuart Hall defines as “the cultural turn” because the audiences participate in the process of meaning production and exchange that circulates inside the circuit of culture.Footnote 102 Hence, the composer aims to teach his students about the connections between culture, society, and music (on-site as well as on-line), in addition to simply teaching traditional composition or piano lessons. Lifchitz's course “Music and Society in Latin America: Past and Present” at SUNY Albany, for instance, is a good example of his approach to interdisciplinary instruction. The goal of the course is to introduce students to the music, life, and culture of Latin America and of Latinx in the United States, from the perspective of the polysemic concept of analogical pluriversality. Consequently, it also illustrates how including distinct narratives, cultures, and scholars in the course content, for example, contrary to the permanent reproduction of canonical knowledge from a dominant cultural and racial group, is an effective action to bring decolonization and equity into the classroom space. Therefore, he advocates for changes that promote and practice the inclusion and equity of ethnicities and genders in classrooms and curricula.Footnote 103 In other words, he joins the voices of those scholars, artists, and citizens who want to transform the modern university experience into a transmodern pluriversity. Lifchitz's educational philosophical approach is aligned to Dussel's philosophical concept of transmodernity in order to decenter the Eurocentric and Euro-American modern and postmodern projects with the aim of opening intercultural dialogues and exchanges that “seek[] to foster new, better, and alternative knowledges and ways of being human.”Footnote 104

Conclusion

Max Lifchitz is a multidimensional artist whose contribution extends beyond his catalog of musical works. As an artist-citizen who displays transmodern characteristics, Lifchitz seeks to transform his reality by using music to create an analectic space in his compositions, in the North/South Consonance Ensemble concert series, and in education. As a member of the Jewish diaspora who was first based in Mexico and then in New York City, Lifchitz's personal and artistic life has contributed significantly to his creation of spaces for analogical dialogue among different ethnocultural groups. In these spaces there is communication between alterities that is distinct from postmodern multiculturalism. Although Lifchitz does not articulate this philosophy verbally (to cite an instance, in interviews), his holistic approach to music shows that he is closer to the ideal of transmodernism than that of postmodernism. In line with Enrique Dussel's theory of transmodernity, Lifchitz believes in a plural world that has the potential for mutual understanding and peace.