Introduction

Nogami (Reference Nogami1966, Reference Nogami1967) published the first studies on Cambrian conodonts recovered from North China. An (Reference An1981, Reference An1982) and An et al. (Reference An, Zhang, Xiang, Zhang, Xu, Zhang, Jiang, Yang, Lin, Cui and Yang1983) greatly expanded systematic studies on Cambrian conodonts of northern and northeastern China. Wang (Reference Wang1985) and Chen and Gong (Reference Chen and Gong1986) focused on conodonts across the Cambrian–Ordovician boundary in northern and northeastern China. Wang and Luo (Reference Wang and Luo1984), An and Zheng (Reference An and Zheng1990), and Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Zhang and Xiao2000) found only sporadic Cambrian conodonts in northwestern China.

An (Reference An1982) used a more biostratigraphic approach. He made good use of the favorable geological conditions in northern and northeastern China, mainly in four key sections in Liaoning, Hebei, and Shandong. There, he founded conodont zones of the Zhangxia Formation (middle Cambrian) through the Fengshan Formation (upper Cambrian). Paraconodont zones below the Fengshan Formation were the first to be proposed for this interval anywhere in the world.

An et al. (Reference An, Du, Gao, Chen and Li1981) also initiated studies of Cambrian conodonts in South China, although they focused on conodonts across the Cambrian–Ordovician boundary. They found Cordylodus proavus Müller, Reference Müller1959 and other important elements, such as Monocostodus sevierensis (Miller, Reference Miller1969), in the dolostone in the top part of the Sanyoudong Formation in Yichang, Hubei. An et al. (Reference An, Du, Gao, Chen and Li1981) first proposed that the Cambrian–Ordovician boundary should be drawn at ~10 m below the top of the Sanyoudong Formation, which previously had been considered to be entirely upper Cambrian. Dong (Reference Dong1983, Reference Dong1985) restudied conodonts in the interval across the Cambrian–Ordovician boundary in Yichang, where he found Cordylodus intermedius Furnish, Reference Furnish1938 and Cordylodus angulatus Pander, Reference Pander1856. Dong founded three conodont assemblage zones in these Yichang strata and proposed that the Cambrian–Ordovician boundary there should be drawn at the base of the Monocostodus sevierensis–Cordylodus intermedius Assemblage Zone, which is 14 m below the top of the Sanyoudong Formation in Yichang. Dong (Reference Dong1987) recognized the Proconodontus Zone, Cordylodus proavus Zone, and C. intermedius Zone in Chuxian, Anhui, South China. Based on conodonts from western Zhejiang and Chuxian, Anhui in South China, Ding et al. (Reference Ding, Cao, Bao and Yang1993a, Reference Ding, Chen, Zhang, Cao, Bao and Yangb) distinguished the Proconodontus Zone and the C. proavus Zone. Western Hunan has a favorable geological setting for systematic studies of Cambrian conodonts in South China because of relatively continuous carbonate deposition, but conodont research there was in a pioneer state before the late 1980s. Xi-ping Dong began studying Cambrian through lowermost Ordovician conodont biostratigraphy and taxonomy in western Hunan in 1985. An and Hu (Reference An and Hu1985) and An (Reference An1987) studied two sections, namely at Luoyixi in Guzhang County and Likouzui in Fenghuang County. Because they recovered only a few Cambrian conodonts, it was not possible to propose conodont zones. Recently, Bagnoli and colleagues did excellent work on the Cambrian conodonts of South China (Qi et al., Reference Qi, Bagnoli and Wang2006; Bagnoli et al., Reference Bagnoli, Qi and Wang2008; Bagnoli and Qi, Reference Bagnoli and Qi2011).

One difficulty in biostratigraphic study of Cambrian conodonts has been the lack of a detailed zonation based on paraconodonts below the upper upper Cambrian. A regionally applicable zonation based on earliest euconodonts, which first appear in the upper upper Cambrian, was largely established in North America in the 1980s and has been improved subsequently (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Evens, Loch, Ethington, Stitt, Holmer and Popov2003). This zonation based on early euconodonts played an important role in delimiting the Cambrian–Ordovician boundary and should prove to be useful in defining the terminal stage of the Cambrian (Miller, Reference Miller1980, Reference Miller1981, Reference Miller1987, Reference Miller1988; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Taylor, Stitt, Ethington, Hintze and Taylor1982, Reference Miller, Ethington, Evans, Holmer, Loch, Popov, Repetski, Ripperdan and Taylor2006, Reference Miller, Evens, Freeman, Ripperdan and Taylor2011, Reference Miller, Evens, Freeman, Ripperdan and Taylor2014a; Forty et al., Reference Fortey, Landing and Skevington1982; Taylor and Landing, Reference Taylor and Landing1982; Nowlan, Reference Nowlan1985; Bagnoli et al., Reference Bagnoli, Barnes and Stevens1987; Barnes, Reference Barnes1988; Fåhræus and Roy, Reference Fåhræus and Roy1993; Landing, 1979, Reference Landing1993; Landing and Westrop, 2006; Landing et al., Reference Landing, Barnes and Stevens1986, Reference Landing, Westrop and van Aller Hernick2003, Reference Landing, Westrop and Keppie2007, Reference Landing, Westrop and Adrain2011; Ji and Barnes, Reference Ji and Barnes1994; Taylor and Repetski, Reference Taylor and Repetski1995; Nicoll et al., Reference Nicoll, Miller, Nowlan, Repetski and Ethington1999; Parsons and Clark, Reference Parsons and Clark1999; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Nowlan and Williams2001; Pyle et al., Reference Pyle, Barnes and Mcanally2007). Since 1982, several of these zones and subzones have been successively recognized in North China (An, Reference An1982; An et al., Reference An, Zhang, Xiang, Zhang, Xu, Zhang, Jiang, Yang, Lin, Cui and Yang1983; Wang, Reference Wang1985; Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986; Nowlan and Nicoll, Reference Nowlan and Nicoll1995), South China (Dong, Reference Dong1985, Reference Dong1987; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Repetski and Bergström2004c), Australia (Nicoll, Reference Nicoll1990, Reference Nicoll1991; Nicoll and Shergold, Reference Nicoll and Shergold1991), Kazakhstan (Dubinina, Reference Dubinina2000), Mexico (Landing et al., Reference Landing, Westrop and Keppie2007), New Zealand (Wright and Cooper, Reference Wright and Cooper1994), Turkey (Göncüoğlu and Kozur, Reference Göncüoğlu and Kozur2000), and South Korea (Lee, Reference Lee2001, Reference Lee2002a, Reference Leeb, Reference Lee2004, Reference Lee2008a, Reference Leeb; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee, Miller and Jeong2009).

Despite all of this published work, conodonts in the middle Cambrian and most of the upper Cambrian have not been recognized worldwide as useful index fossils. There are several reasons for this. First, trilobites have been, and remain, the key fossils for biostratigraphic subdivision and correlation of Cambrian rocks, and most biostratigraphic studies have been centered on this group. Other groups, including conodonts, were largely neglected until the late 1960s. Second, the routine technique of etching samples with acetic acid for conodonts is suitable for processing only carbonate rocks. Conodonts are generally rare or absent in many dolostones, so only limestones are suitable in most cases for large-scale processing. However, continuously deposited and well-exposed middle Cambrian to Lower Ordovician limestone successions occur only in a few countries, such as China. Third, there has been a tendency among many conodont workers to consider the Cambrian paraconodont taxa to be stratigraphically long ranging and hence of limited use for stratigraphic subdivision and correlation.

In Europe, the well-studied middle to upper Cambrian sections in Scandinavia are stratigraphically very condensed, and the trilobite biostratigraphy has been well studied. These strata have particularly great potential for study of paraconodonts. Conodont faunas in these successions were described in a magnificent monograph by Müller and Hinz (Reference Müller and Hinz1991). However, because the aim of their study was taxonomic rather than biostratigraphic, they focused their sampling on fossiliferous limestone nodules in the black shale succession. The age of each sample was subsequently established based on the trilobite taxa present. As a result, ranges of conodont species are known only in terms of trilobite zones, and the range of each conodont taxon within a specific trilobite zone is currently unknown unless it is present in the overlying and underlying zones. Müller and Hinz (Reference Müller and Hinz1991) established no conodont zones, but their study suggests that many taxa are long ranging, although some of their species have restricted stratigraphic ranges (Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, table 2). It seems likely that their classic monograph has contributed to the belief that many paraconodonts are stratigraphically long ranging and hence of limited biostratigraphic use. In addition, several other studies in Europe and elsewhere have been mainly general or taxonomic in nature, with relatively little attention paid to the potential use of especially paraconodonts as guide fossils (Müller, Reference Müller1959).

The fourth factor contributing to the lack of established Cambrian paraconodont biostratigraphy in most regions of the world is the lack of detailed research. Outside of China, there has been relatively little conodont research in strata older than the late late Cambrian, especially compared with the extensive work on euconodonts from younger rocks. For instance, many promising Cambrian sections in eastern and western North America remain unexplored for conodonts (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Bergström and Repetski2004a). For the past 25 years, the middle and lower upper Cambrian conodont biostratigraphic work in the world has largely been centered in China, and especially in South China.

The purpose of this paper is to describe conodonts of the upper Cambrian (Furongian Series) through lowermost Ordovician from Hunan, South China and to redescribe conodonts of the middle Cambrian, based on the material that has been accumulated for the past quarter century. The taxonomy of some conodont genera is revised. In light of histological investigation, some genera can now be assigned to euconodonts, paraconodonts, or protoconodonts.

Geological setting

In terms of the paleogeography of China, the Southeast Stratigraphic Region is characterized by flyschoid sediments. In the Yangtze Stratigraphic Region, the middle and upper Cambrian succession mainly is composed of dolostone. Only in the Langyashan Subregion does the middle and upper Cambrian consist mainly of dolomitic limestone. The upper part of the middle Cambrian through the lowermost Ordovician is made up chiefly of limestone in the Danzai-Baojing-Qinyang Subregion of the Jiangnan Stratigraphic Region. Within that area, mainly in western Hunan, are well-developed and continuously deposited stratigraphic successions. Accordingly, western Hunan is an ideal area for the study of Cambrian conodonts in South China.

Three sections in Hunan were selected as key sections. These are the Paibi section in Huayuan County, the Wangcun section in Yongshun County, and Wa’ergang section in Taoyuan County. Three other sections in Hunan were selected as auxiliary sections, including the Xiaoxi section in Jishou County, the Xiaoxiqiao section in Qianzhou, and the Yangjiazhai section in Jishou. Two additional sections in Hunan were selected as reference sections; these are the Tieqiao to Liangshuijing section in Fenghuang County and the Huaqiao section in Baojing County (Fig. 1). Some of the data gathered from these investigations have been published (Dong, Reference Dong1990a, Reference Dongb, Reference Dong1991, Reference Dong1992, Reference Dong1993, Reference Dong1997, Reference Dong1999a, Reference Dongb, Reference Dubinina2000, Reference Dong2001; Dong and Bergström, Reference Dong and Bergström2000a, Reference Dong and Bergströmb, Reference Dong and Bergström2001a, Reference Dong and Bergströmb; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Repetski and Bergström2001, Reference Dong, Repetski and Bergström2004a, Reference Dong, Bergström and Repetskic). The present study is the continuation of these previous studies and includes the first systematical description of the conodonts of upper Cambrian through lowermost Ordovician from Hunan, South China, taxonomic revision of some Cambrian conodonts, review of the problems in the zonation of paraconodonts recovered from western Hunan, South China, and assignment of some genera to euconodonts, paraconodonts, or protoconodonts in light of histological investigation.

Figure 1 Location of the studied sections: ☆ Location of the key sections, ▲ location of the auxiliary sections, △ location of the reference sections.

Conodont samples were collected from the three key sections on 15 occasions from 1986 to 2008 and from the three auxiliary sections from 1986 to 1995. The two reference sections were collected only sporadically, in 1986 and 1987. The average sampling interval is 2.5 m and the average sample mass is 4.6 kg. A total of 3,100 conodont samples have been collected, including re-sampled ones and 388 conodont-barren samples, with a total mass of more than 14,000 kg.

In the study area, there are mainly five types of lithology in the interval from the middle Cambrian Huaqiao Formation to the lower part of the lowermost Ordovician Panjiazui Formation.

-

1. Dark-gray, thin-bedded to medium- to thin-bedded, laminated, argillaceous, very fine to finely crystalline limy dolostone. Protoconodonts, but almost no other fossils, occur in this lithology.

-

2. Alternating layers of dark-gray, medium-bedded, laminated, argillaceous dolostone, and dark gray, medium-bedded micrite and biomicrite. The argillaceous dolostone does not yield fossils, whereas the limestones yield abundant conodonts, fossil embryos (Dong, Reference Dong2007a, Reference Dong2009a, Reference Dongb; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Donoghue, Cheng and Liu2004b, Reference Dong, Donoghue, Cunningham, Liu and Cheng2005a, Reference Dong, Bengtson, Gostling, Cunningham, Harvey, Kouchinsky, Val’kov, Repetski, Stampanoni, Marone and Donoghue2010; Peng and Dong, Reference Peng and Dong2008; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Peng, Duan and Dong2011), fossils of typical Orsten-type preservation (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Donoghue, Liu, Liu and Peng2005b; Liu and Dong, Reference Liu and Dong2007, Reference Liu and Dong2009, Reference Liu and Dong2010; Zhang and Dong, Reference Zhang and Dong2009; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Dong and Maas2011a, Reference Zhang, Dong and Xiaob, Reference Zhang, Dong and Xiao2012; Duan et al., Reference Duan, Dong and Donoghue2012), highly modified sponge spicules (Dong and Knoll, Reference Dong and Knoll1996; Chen and Dong, Reference Chen and Dong2008), radiolarians (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Knoll and Lipps1997), small shelly fossils (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Dong and Chen2003, Reference Zhu, Li and Dong2004; Zhu and Dong, Reference Zhu and Dong2004), as well as trilobites and brachiopods.

-

3. Dark-gray, thin- to medium-bedded biomicrosparite that yields abundant conodonts as well as some trilobites, brachiopods, and bradoriids.

-

4. Gray, thick-bedded calcirudite. Fragmentary trilobites have been found occasionally in this lithology. No conodont samples have been collected from this lithology.

-

5. Dark-gray, thin-bedded micrite intercalated with dark-gray, thin-bedded to laminated, dolomitic calcisiltite, containing organic matter and scattered pyrite. Burrows and bioturbation may occur. The micrite yields abundant conodonts, as well as trilobites, brachiopods, small shelly fossils, sponge spicules, and radiolarians.

Except for type 4, the calcirudites, the other four types of lithology were collected with specific sampling intervals from the key sections and auxiliary sections on the first sampling round. Mainly type 2, type 3, and type 5 were collected from the key sections during the second and third sampling rounds. Mainly type 3 and type 5 were collected during the fourth to the twelfth sampling rounds. The purpose of the fourth to the fifteenth sampling rounds was to recover, in addition to conodonts, sponge spicules, radiolarians, and soft-bodied fossils, such as embryos, and typical Orsten-type fossils, especially arthropods.

Materials and methods

The samples were processed by routine etching with ~10% technical acetic acid in plastic pails with a capacity of 10 L. The cycle of sieving and changing acid required 7–10 days. The samples (including duplicate samples) generally needed to be processed in three to four cycles for complete dissolution. During processing, the reaction time and the pH value of the solution were adjusted according to the lab temperature (~20°C in winter and up to 35°C in July and August). Some samples were processed in plastic pails with two-layered screens to recover better specimens for histologic studies as well as for recovery of phosphatized soft-bodied fossils. Results using the two-layered screens were very good.

For histological study, protoconodont-like elements were examined by double-polished thin sections and by etching both the thin sections and artificially fractured specimens with 0.5% orthophosphoric acid for 10 minutes, and then their images were taken by scanning electron microscope. Because of the small size and thin-walled nature of these paraconodonts and earliest euconodonts, the oil immersion technique is used for those elements (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Donoghue and Repetski2005c). Clove oil was used as the immersion medium, and specimens were examined using a Zeiss Axiophot or Olympus microscope fitted with differential interference contrast (Nomarski) optics. Photomicrographs were obtained using a Nikon Coolpix 990 or Olympus BH2 BHS UMA camera fitted via a c-mount and interchange lens to the microscope.

Repository and institutional abbreviation.—

All the figured specimens are deposited at the Geological Museum, Peking University (GMPKU).

Chronostratigraphy

The Ordovician is divided into Lower, Middle, and Upper Ordovician series. The current classification of Cambrian is divided into four series; Series 2 and Series 3 have not been formally named. The Terreneuvian and Series 2 are sometimes informally referred to as lower Cambrian, Series 3 is sometimes informally referred to as middle Cambrian, and the fourth series, the Furongian Series, is sometimes referred to as upper Cambrian. Therefore, we use the term Lower Ordovician formally, but also use the terms middle Cambrian and upper Cambrian informally.

Conodont biostratigraphy

Based on the stratigraphic ranges of conodont species, the middle Cambrian through lowermost Ordovician succession at Wangcun, Wa’ergang, and Paibi, South China, is subdivided into 13 conodont zones (Figs. 2–4; see also Dong and Bergström, Reference Dong and Bergström2001a).

Figure 2 Chart showing the stratigraphic ranges of the upper middle Cambrian through upper Cambrian (Furongian) conodonts and conodont zones in the Wangcun section in Hunan, China.

Figure 3 Chart showing the stratigraphic ranges of the upper middle Cambrian through lowermost Ordovician conodonts and conodont zones in the Wa’ergan section in Hunan, China.

Figure 4 Chart showing the stratigraphic ranges of the upper middle Cambrian conodonts and conodont zones in the Paibi section in Hunan, China (modified after Dong and Bergström, Reference Dong and Bergström2001a).

Gapparodus bisulcatus-Westergaardodina brevidens Zone.—

This zone is recognized in the lower part of the middle Cambrian Huaqiao Formation in the Paibi section, Huayuan and in the Wangcun section, Yongshun. Its lower limit is marked by the First Appearance Datum (FAD) of Gapparodus bisulcatus (Müller, Reference Müller1959), and its upper limit is defined by the FAD of Shandongodus priscus An, Reference An1982. The entire zone is characterized the dominance of protoconodonts and the first occurrence and high diversity of the genus Westergaardodina Müller, Reference Müller1959. The main taxa of the zone are Furnishina bigeminata Dong, Reference Dong1993, F. kleithria Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, G. bisulcatus, Gumella cuneata Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, Huayuanodontus tricornis (Dong, Reference Dong1993), Laiwugnathus hunanensis n. sp., Muellerodus? oelandicus (Müller, Reference Müller1959), Paibiconus proarcuatus Dong, Reference Dong1993, Phakelodus tenuis (Müller, Reference Müller1959), Westergaardodina brevidens Dong, Reference Dong1993, W. horizontalis Dong, Reference Dong1993, and Yongshunella polymorpha Dong and Bergström, 2001a.

Shandongodus priscus-Hunanognathus tricuspidatus Zone.—

This zone is recognized in the upper part of the middle Cambrian Huaqiao Formation in the Paibi and Wangcun sections. Its lower limit is defined by the FAD of Shandongodus priscus and its upper limit by the FAD of Westergaardodina quadrata (An, Reference An1982). It is characterized by the extreme diversity of paraconodonts and the maximum numbers of protoconodonts. Its main taxa are Coelocerodontus bicostatus van Wamel, Reference van Wamel1974, Furnishina cf. alata Szaniawski, Reference Szaniawski1971, F. cf. gladiata Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, F. cf. kranzae Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, F. longibasis Bednarczyk, Reference Bednarczyk1979, F. pernica An, Reference An1982, F. cf. quadrata Müller, Reference Müller1959, Hunanognathus tricuspidatus Dong, Reference Dong1993, Muellerodus? obliquus (An, Reference An1982), M. pomeranensis (Szaniawski, Reference Szaniawski1971), Nogamiconus sinensis (Nogami, Reference Nogami1966), S. priscus, Westergaardodina elegans Dong and Bergström, 2001a, W. tetragonia Dong, Reference Dong1993, and Westergaardodina sp. D. In addition, there are taxa ranging upward from the underlying zone, including F. bigeminata, Gapparodus bisulcatus, Gumella cuneata, Huayuanodontus tricornis, M.? oelandicus, Paibiconus proarcuatus, Phakelodus tenuis, W. brevidens, and Yongshunella polymorpha.

Westergaardodina quadrata Zone.—

This zone can be recognized in the lower part of the middle Cambrian Chefu Formation in the Paibi and Wangcun sections. Its lower limit is defined by the FAD of Westergaardodina quadrata and its upper limit by the FAD of W. matsushitai Nogami, Reference Nogami1966. It is characterized by the great abundance of W. quadrata. Its main taxa are Furnishina quadrata Müller, Reference Müller1959, Prosagittodontus compressus n. sp., W. cf. behrae Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, W. quadrata, W. cf. quadrata and W. sola n. sp. In addition, there are taxa ranging into this zone from the underlying zone, such as Furnishina cf. alata, F. bigeminata, F. kleithria, F. longibasis, F. pernica, F. cf. quadrata, Gapparodus bisulcatus, Gumella cuneata, Huayuanodontus tricornis, Hunanognathus tricuspidatus, Nogamiconus sinensis, Muellerodus? obliquus, M.? oelandicus, M. pomeranensis, Paibiconus proarcuatus, Phakelodus tenuis, W. elegans, W. tetragonia, and Yongshunella polymorpha.

Westergaardodina matsushitai-Westergaardodina grandidens Zone.—

This zone can be recognized in the upper part of the middle Cambrian Chefu Formation in the Paibi, Wangcun, and Wa’ergang sections. Its base is marked by the FAD of Westergaardodina matsushitai, and its top is defined by the FAD of Westergaardodina lui Dong, Repetski, and Bergström, 2004c. It is characterized by a notable reduction in the number of protoconodonts and by the occurrence of morphologically unusual species of Westergaardodina. Its main elements are Laiwugnathus transitans n. sp., L. cf. kouzhenensis An, Reference An1982, Prosagittodontus dahlmani (Müller, Reference Müller1959), Westergaardodina cf. horizontalis Dong, Reference Dong1993, W. gigantea n. sp., W. grandidens Dong, Reference Dong1993, and W. matsushitai. In addition, there are taxa ranging from the underlying zone, such as Coelocerodontus bicostatus, Furnishina cf. alata, F. bigeminata, F. cf. kranzae, F. longibasis, F. quadrata, F. cf. quadrata, Gapparodus bisulcatus, Gumella cuneata, Huayuanodontus tricornis, Muellerodus? obliquus, M.? oelandicus, M. pomeranensis, Nogamiconus sinensis, Paibiconus proarcuatus, Phakelodus tenuis, Prosagittodontus compressus n. sp., W. elegans, W. cf. quadrata, W. sola n. sp., W. quadrata and Yongshunella polymorpha.

Westergaardodina lui-Westergaardodina ani Zone.—

This zone occurs in the lower part of the upper Cambrian Bitiao Formation in the Wangcun and Wa’ergang sections. This zone supersedes the Westergaardodina proligula Zone as used in Dong and Bergström (Reference Dong and Bergström2001a). Its lower boundary is defined by the FAD of W. lui, and its top by the FAD of W. cf. calix Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991. It is characterized by a notable reduction of the diversity of species of Westergaardodina compared with strata below. Its main taxa are Furnishina dayangchaensis Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986, F. furnishi Müller, Reference Müller1959, F. cf. furnishi Müller, Reference Müller1959, F. gladiata Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, F. kranzae Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, F. primitiva Müller, Reference Müller1959, F. tortilis (Müller, Reference Müller1959), F. cf. ovata Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, Muellerodus cambricus (Müller, Reference Müller1959), M. guttulus Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, Proacodus obliquus Müller, Reference Müller1959, P. pulcherus (An, Reference An1982), Prooneotodus gallatini (Müller, Reference Müller1959), P. terashimai (Nogami, Reference Nogami1967), Prosagittodontus cf. eureka Müller, Reference Müller1959, Wangcunella conicus n. gen. n. sp., Wangcunognathus elegans n. gen. n. sp., Westergaardodina ahlbergi Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, W. ani Dong et al., Reference Dong, Donoghue, Cheng and Liu2004c, W. dimorpha n. sp., W. lui, W. microdentata Zhang in An et al., Reference An, Zhang, Xiang, Zhang, Xu, Zhang, Jiang, Yang, Lin, Cui and Yang1983, W. tricuspidata Müller, Reference Müller1959, and Westergaardodina sp. B. In addition, there are taxa that continue from the underlying zone, such as Coelocerodontus bicostatus, F. bigeminata, F. cf. kranzae, F. cf. gladiata, F. longibasis, F. quadrata, F. cf. quadrata, Gapparodus bisulcatus, Gumella cuneata, Huayuanodontus tricornis, Laiwugnathus transitans n. sp., M.? obliquus, M.? oelandicus, M. pomeranensis, Nogamiconus sinensis, Phakelodus tenuis, Prosagittodontus compressus n. sp., P. dahlmani, W. elegans, and Yongshunella polymorpha.

Westergaardodina cf. calix-Prooneotodus rotundatus Zone.—

This zone is recognized in the upper part of the upper Cambrian Bitiao Formation in the Wangcun and Wa’ergang sections. This zone supercedes the Westergaardodina cf. behrae-Prooneotodus rotundatus Zone as used in Dong and Bergström (Reference Dong and Bergström2001a). Its base is marked by the FAD of Westergaardodina cf. calix and its upper limit by the FAD of Proconodontus tenuiserratus Miller, Reference Miller1980. It is characterized by the maximum number of species of Prooneotodus observed in the various zones. Its main taxa are Furnishina wangcunensis n. sp., Granatodontus ani (Wang, Reference Wang1985), Hispidodontus resimus Nicoll and Shergold, Reference Nicoll and Shergold1991, Prooneotodus rotundatus (Druce and Jones, Reference Druce and Jones1971), Serratocambria minuta Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, Tujiagnathus gracilis n. gen. n. sp., W. cf. calix, W. wimani Szaniawski, Reference Szaniawski1971, Westergaardodina sp. A., and Westergaardodina sp. E. In addition, there are taxa ranging from the underlying zone, such as Coelocerodontus bicostatus, F. bigeminata, F. dayangchaensis, F. furnishi, F. cf. furnishi, F. kleithria, F. cf. kranzae, F. cf. gladiata, F. longibasis, F. cf. ovata, F. cf. quadrata, Huayuanodontus tricornis, Muellerodus cambricus, M.? oelandicus, M. pomeranensis, M.? obliquus, Phakelodus tenuis, Proacodus obliquus, P. pulcherus, Prooneotodus terashimai, Prosagittodontus dahlmani, Wangcunella conicus n. gen. n. sp., Westergaardodina ani, W. lui, and W. tricuspidata.

Proconodontus tenuiserratus Zone.—

This zone can be recognized in the lower part of the upper Cambrian Shengjiawan Formation in the Wa’ergang section. Its lower boundary is defined by the FAD of Proconodontus tenuiserratus and its upper boundary by the FAD of Proconodontus muelleri Miller, Reference Miller1969. Its main taxa are Coelocerodontus hunanensis n. sp., Millerodontus intermedius n. gen. n. sp., and P. tenuiserratus. In addition, there are taxa ranging from the underlying zone upward into this zone, such as Coelocerodontus bicostatus, Furnishina bigeminata, F. dayangchaensis, F. furnishi, Granatodontus ani, Huayuanodontus tricornis, Muellerodus cambricus, M.? oelandicus, Phakelodus tenuis, Proacodus obliquus, Prooneotodus gallatini, P. terashimai, P. rotundatus, Wangcunella conicus n. gen. n. sp., Westergaardodina ani, W. lui, and W. cf. calix.

Proconodontus Zone.—

This zone is recognized in the lower part of the upper Cambrian Shengjiawan Formation in the Wangcun and Wa’ergang sections. In addition, this zone can be identified in the upper Cambrian Cheshuitong Formation in Chuxian, Anhui (Dong, Reference Dong1987). Its lower and upper limits are defined by the FAD of Proconodontus muelleri and Eoconodontus notchpeakensis (Miller, Reference Miller1969), respectively. Its main taxa are Dasytodus transmutatus (Xu and Xiang in An et al., Reference An, Zhang, Xiang, Zhang, Xu, Zhang, Jiang, Yang, Lin, Cui and Yang1983), P. muelleri, P. posterocostatus Miller, Reference Miller1980, P. serratus Miller, Reference Miller1980, and Proacodus cf. pulcherus (An, Reference An1982). In addition, there are taxa that range from the underlying zone into this zone, such as Coelocerodontus bicostatus, C. hunanensis n. sp., Furnishina bigeminata, F. furnishi, F. cf. furnishi, F. dayangchaensis, F. cf. ovata, Granatodontus ani, Millerodontus intermedius n. gen. n. sp., Muellerodus cambricus, M.? obliquus, M.? oelandicus, Phakelodus tenuis, Proacodus obliquus, P. pulcherus, Proconodontus tenuiserratus, Prooneotodus gallatini, P. terashimai, P. rotundatus, Prosagittodontus dahlmani, Wangcunella conicus n. gen. n. sp., Westergaardodina ani, W. lui, and W. cf. calix.

Eoconodontus Zone.—

This zone can be recognized in the upper part of the upper Cambrian Shengjiawan Formation in the Wa’ergang section. Its lower and upper boundaries are defined by the FAD of Eoconodontus notchpeakensis and Cordylodus proavus, respectively. Its main taxa are E. notchpeakensis, Lugnathus hunanensis n. gen. n. sp., Hirsutodontus nodus (Zhang and Xiang, 1983), Mamillodus ruminates Dubinina, Reference Dubinina2000, Miaognathus multicostatus n. gen. n. sp., Prooneotodus? sp. A, Teridontus nakamurai (Nogami, Reference Nogami1967), Westergaardodina cf. nogamii Müller Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, and Westergaardodina sp. C. In addition, there are taxa ranging from the underlying zone into this zone, such as Coelocerodontus bicostatus, C. hunanensis n. sp., Furnishina bigeminata, F. dayangchaensis, F. furnishi, F. cf. furnishi, F. primitiva, F. cf. ovata, Dasytodus transmutatus, Granatodontus ani, Millerodontus intermedius n. gen. n. sp., Muellerodus cambricus, M.? oelandicus, Phakelodus tenuis, Proacodus obliquus, Prooneotodus gallatini, P. terashimai, P. rotundatus, Proconodontus muelleri, P. posterocostatus, P. serratus, Prosagittodontus dahlmani, Wangcunella conicus n. gen. n. sp., Westergaardodina cf. calix, W. ani, and W. lui.

Cordylodus proavus Zone.—

This zone is recognized in the upper part of the upper Cambrian Shengjiawan Formation in the Wa’ergang section. Moreover, this zone can be recognized in the upper Cambrian Cheshuitong Formation at Chuxian, Anhui (Dong, Reference Dong1987). Its lower and upper boundaries are defined by the FAD of Cordylodus proavus and C. intermedius Furnish, Reference Furnish1938, respectively. Its main taxa are C. proavus and Eodentatus bicuspatus Nicoll and Shergold, Reference Nicoll and Shergold1991. In addition, there are taxa ranging from the underlying zone, such as Coelocerodontus bicostatus, C. hunanensis n. sp., Dasytodus transmutatus, Eoconodontus notchpeakensis, Furnishina bigeminata, F. furnishi, F. dayangchaensis, F. primitiva, Lugnathus hunanensis n. gen. n. sp., Muellerodus? oelandicus, Phakelodus tenuis, Prooneotodus gallatini, P. rotundatus, P. terashimai, Prosagittodontus dahlmani, Teridontus nakamurai, Westergaardodina cf. calix, W. ani, and W. lui.

Cordylodus intermedius Zone.—

This zone is recognized in the lowermost part of the Panjiazui Formation in the Wa’ergang section. It can also be recognized in the lowermost part of the Cheshuitong Formation in Chuxian, Anhui (Dong, Reference Dong1987); that formation originally was assigned to the Lower Ordovician. Its lower boundary is marked by the FAD of Cordylodus intermedius, and its upper boundary by the FAD of C. lindstromi Druce and Jones, Reference Druce and Jones1971. Its main taxa are C. intermedius and C. prolindstromi Nicoll, Reference Nicoll1991. In addition, there are taxa ranging from the underlying zone, such as Coelocerodontus bicostatus, C. hunanensis n. sp., Cordylodus proavus, Eoconodontus notchpeakensis, Furnishina primitiva, Lugnathus hunanensis n. gen. n. sp., Muellerodus? oelandicus, Phakelodus tenuis, Prooneotodus gallatini, P. rotundatus, Teridontus nakamurai, Westergaardodina ani, W. cf. calix, and W. lui.

Cordylodus lindstromi Zone.—

This zone is recognized in the lower part of the Panjiazui Formation in the Wa’ergang section. Its lower and upper boundaries are defined by the FAD of Cordylodus lindstromi and C. angulatus, respectively. Its main taxa are C. caseyi Druce and Jones, Reference Druce and Jones1971, C. lindstromi, Iapetognathus fluctivagus Nicoll, Miller, Nowlan, Repetski, and Ethington, Reference Nicoll, Miller, Nowlan, Repetski and Ethington1999, I. jilinensis Nicoll, Miller, Nowlan, Repetski, and Ethington, Reference Nicoll, Miller, Nowlan, Repetski and Ethington1999, and Monocostodus sevierensis. Taxa that continue from the underlying zone include Coelocerodontus bicostatus, Cordylodus intermedius, C. proavus, C. prolindstromi, Eoconodontus notchpeakensis, Lugnathus hunanensis n. gen. n. sp., Phakelodus tenuis, Teridontus nakamurai, and Westergaardodina ani.

Cordylodus angulatus Zone (lower part).—

This zone is recognized in the lower part of the Panjiazui Formation in the Wa’ergang section. Its lower limit is defined by the FAD of Cordylodus angulatus, but its upper limit is not delimited herein because the upper portion of this zone is beyond the scope of the present study. Its main taxa are C. angulatus and Iapetognathus aengensis (Lindström, Reference Lindström1955). In addition, there are taxa that range from the underlying zone, such as C. intermedius, C. lindstromi, Monocostodus sevierensis, and Teridontus nakamurai.

Correlation of conodont zones

The formal conodont zonation older than the Fengshan Formation in North China and the Shengjiawan Formation in South China (Furongian, upper Cambrian) has been mainly established in China (Figs. 5, 6). Outside China, the middle Cambrian conodont zone Gapparodus bisulcatus-Westergaadodina mossebergensis is erected in the lower part of the Machari Formation, Yeongweol area, Gangweon Province, in South Korea (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee, Miller and Jeong2009).

Figure 5 Correlation of the upper middle Cambrian through lowermost Ordovician conodont zones in Hunan, South China, and those in North China, western USA, and Newfoundland, Canada.

Figure 6 Correlation between the conodont zones and trilobite zones of the upper middle Cambrian through lowermost Ordovician in Hunan, South China.

At present, the paraconodont zones below the Shengjiawan Formation in Hunan can be correlated only with those in North China (An, Reference An1982; Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986). In contrast, eucondont zones in Hunan can be correlated widely with related zones in North China and elsewhere (Fig. 5).

Gapparodus bisulcatus-Westergaardodina brevidens Zone.—

In terms of species, this zone shares only a few elements with the Laiwugnathus laiwuensis Zone of North China (An, Reference An1982). The upper boundary of the Hunan zone and the L. laiwuensis Zone are both marked by the FAD of Shandongodus priscus, so the top of both zones may be correlated. In Hunan, the lowest occurrence of Gapparodus bisulcatus is in the lowermost part of the middle Cambrian Huaqiao Formation, and this level is equivalent to the lowest occurrence of the trilobite Ptychagnostus atavus (Tullberg, Reference Tullberg1880). The lowest occurrence of P. atavus in Hunan corresponds to that of Crepicephalina Resser and Endo in Kobayashi, 1935 in North China (Peng, Reference Peng2009a). Accordingly, it is inferred that the lower part of the G. bisulcatus-Westergaardodina brevidens Zone correlates with the lower part of the Zhangxia Formation in North China (Fig. 6).

Shandongodus priscus-Hunanognathus tricuspidatus Zone.—

This zone shares the zonal index species Shandongodus priscus with the S. priscus Zone in North China, so the two zones can be easily correlated with each other. The bases of the two zones are marked by the FAD of S. priscus, so the bases of these zones may be correlated. The top of the S. priscus-Hunanognathus tricuspidatus Zone in Hunan is marked by the FAD of Westergaardodina quadrata. W. quadrata and Westergaardodina orygma are associated in North China, and their FAD is at the same horizon. Accordingly, the top of the S. priscus-H. tricuspidatus Zone in Hunan appears to be identical to that of the S. priscus Zone in North China.

Westergaardodina quadrata Zone.—

Westergaardodina quadrata and W. orygma occur together and basically have the same range in the W. orygma Zone in North China. The base of both these zones precisely corresponds with each other. Because the tops of both zones are defined by the FAD of W. matsushitai, these zones represent the same stratigraphic interval, and the W. quadrata Zone in South China is equivalent to the W. orygma Zone in North China.

Westergaardodina matsushitai-Westergaardodina grandidens Zone.—

Westergaardodina matsushitai occurs in the W. matsushitai Zone in Hunan and in North China (An, Reference An1982). As mentioned above, the bases of both zones are defined in the same way and hence represent the same stratigraphic level. The top of the Hunan zone is defined by the FAD of W. lui, which is only a few meters higher than the last occurrence of W. grandidens and W. matsushitai, so it is nearly identical to the top of the latter zone. Therefore, the Hunan zone is correlated with the W. matsushitai Zone in North China.

Westergaardodina lui-Westergaardodina ani Zone.—

In Hunan, this zone shares only Proacodus pulcherus with the fauna of the Muellerodus? erectus Zone in North China (An, Reference An1982; Dong and Bergström, Reference Dong and Bergström2001a; Dong et al., 2004c). The base of the Hunan zone is defined by the FAD of Westergaardodina lui, and the base of the North China zone is defined by the last occurrence of W. matsushitai. In Hunan, the FAD of W. lui is only a few meters higher than the last occurrence of W. matsushitai and W. grandidens. Accordingly, the bases of both zones are roughly coeval. The top of the Hunan zone is marked by the FAD of W. cf. calix, whereas the top of the North China zone is defined as the level of the last appearance of M.? erectus. Precise correlation of the tops of these zones is difficult, and these zones are only approximately equivalent to each other.

Westergaardodina cf. calix-Prooneotodus rotundatus Zone.—

This zone shares Prooneotodus terashimai, and abundant P. gallatini with the Westergaardodina aff. fossa-P. rotundatus Zone in North China (An, Reference An1982; Dong and Bergström, Reference Dong and Bergström2001a; Dong et al., 2004c). The bases of both zones are broadly equivalent. The tops of both these zones are marked by the FAD of Proconodontus tenuiserratus, so these zones appear to represent the same stratigraphic interval.

Proconodontus tenuiserratus Zone.—

Proconodontus tenuiserratus occurs in the P. tenuiserratus Zone in Hunan, in the P. tenuiserratus Zone in North China (An, Reference An1982; Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986), and in the western United States of America (Miller, Reference Miller1988; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Evens, Loch, Ethington, Stitt, Holmer and Popov2003). Because of the rather short stratigraphic range of this species, this zone in these three regions can be approximately correlated with one another.

Proconodontus Zone.—

Proconodontus muelleri and Teridontus nakamurai occur in the Proconodontus Zone in Hunan and in North China (An, Reference An1982; Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986), and both taxa are also present in western USA (Miller, Reference Miller1988; Nicoll et al., Reference Nicoll, Miller, Nowlan, Repetski and Ethington1999; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Evens, Loch, Ethington, Stitt, Holmer and Popov2003). Because P. posterocostatus has been found only in two horizons in Hunan, the P. posterocostatus Subzone and the P. muelleri Subzone recognized in North China cannot be distinguished in Hunan. However, the Proconodontus Zone in Hunan roughly corresponds to the Proconodontus Zone in North China (An, Reference An1982; Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986). The Hunan zone corresponds to the interval of both the P. posterocostatus Zone and the P. muelleri Zone recognized in the western USA (Miller, Reference Miller1988; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Evens, Loch, Ethington, Stitt, Holmer and Popov2003).

Eoconodontus Zone.—

Eoconodontus notchpeakensis occurs in the Eoconodontus Zone in Hunan and in the Cambrooistodus Zone of North China (Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986) and in the Eoconodontus Zone in the western USA (Miller, Reference Miller1988; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Evens, Loch, Ethington, Stitt, Holmer and Popov2003, Reference Miller, Evens, Freeman, Ripperdan and Taylor2014a). In the western United States, the Eoconodontus Zone is subdivided into the E. notchpeakensis Subzone and the Cambrooistodus minutus Subzone. The correlation between these subzones and the Cambrooistodus Zone in North China (Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986) is not clear because in North China the lowest part of the range of E. notchpeakensis is within the Proconodontus Zone (Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986, text-fig. 26), and a separate Eoconodontus Zone is not recognized there. Cambrooistodus is not found in Hunan, and the Cambrooistodus Zone is only recognized at Dayangcha, North China in the warm (shallow) water realm (Miller, Reference Miller1988, fig. 3). The Eoconodontus Zone in Hunan is interpreted as broadly equivalent with the Eoconodontus Zone in the western United States (Miller, Reference Miller1988) and with the Cambrooistodus Zone of North China (Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986). The Eoconodontus Zone in Hunan also roughly corresponds with the E. notchpeakensis Zone in western Newfoundland, Canada (Barnes, Reference Barnes1988), and with the Eoconodontus Zone in Black Mountain, western Queensland, Australia (Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Nicoll, Laurie and Radke1991).

Cordylodus proavus Zone.—

Cordylodus proavus occurs in the C. proavus Zone in Hunan and in the C. proavus Zone in North China (An, Reference An1982; Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986), and the two zones can be correlated with each other. The base of the zone is marked by the FAD of C. proavus and the top by the FAD of C. intermedius. The C. proavus Zone in Hunan is also correlated with the C. proavus Zone in the western USA (Miller, Reference Miller1980, Reference Miller1988; Nicoll et al., Reference Nicoll, Miller, Nowlan, Repetski and Ethington1999; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Evens, Loch, Ethington, Stitt, Holmer and Popov2003), and with the interval containing the proavus Fauna in western Newfoundland (Barnes, Reference Barnes1988; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Nowlan and Williams2001).

Cordylodus intermedius Zone.—

This zone is recognized worldwide. In the western United States, according to Miller (Reference Miller1988), “the base of the Cordylodus intermedius Zone is at the lowest occurrence of several euconodonts (Hirsutodontus simplex, Monocostodus sevierensis, Semiacontiodus lavadamensis, Utahconus utahensis, and C. intermedius), and the paraconodont Albiconus postcostatus Miller, Reference Miller1980. In some sections, all of these species begin at the same level or if one occurs below the others, it is often H. simplex.” The C. intermedius Zone is divided into the H. simplex and Clavohamulus hintzei Subzones in the western United States. In the Dayangcha sections in northeastern China, the first appearance of C. intermedius, H. simplex, U. utahensis, S. lavadamensis, M. sevierensis, and A. postcostatus is at the same, or nearly the same, horizon, so the base of the C. intermedius Zone there correlates with the base of the H. simplex Subzone of the North American zonal scheme (Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986). However, H. simplex and C. hintzei have not yet been found in Hunan, probably because these two species were shallow water taxa. Rare specimens of these species have been found at the Green Point section, Newfoundland, but these specimens may be reworked from shallow water platform strata (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Nowlan and Williams2001). The precise correlation of the C. intermedius Zone in Hunan with the C. intermedius Zone in other regions is somewhat unclear. This is particularly the case with correlation of the top of the C. intermedius Zone in Hunan with that of the C. intermedius zones in other regions. Therefore, we interpret the C. intermedius Zone in Hunan as only roughly equivalent to the C. intermedius Zone in North China (Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986), the C. intermedius Zone in the western United States (Miller, Reference Miller1988; Nicoll et al., Reference Nicoll, Miller, Nowlan, Repetski and Ethington1999; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Evens, Loch, Ethington, Stitt, Holmer and Popov2003), and the interval of the intermedius Fauna in western Newfoundland (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Nowlan and Williams2001).

Cordylodus lindstromi Zone.—

This zone is recognized widely in the world. We tentatively consider the Cordylodus lindstromi Zone in Hunan as broadly corresponding to the C. lindstromi Zone in North China (Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986). The Hunan zone corresponds to the combined Iapetognathus Zone and the Cordylodus lindstromi Zone in the western USA (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Hintze, Ethington, Miller, Taylor and Repetski1997; Nicoll et al., Reference Nicoll, Miller, Nowlan, Repetski and Ethington1999; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Evens, Loch, Ethington, Stitt, Holmer and Popov2003), and roughly to the Iapetognathus fluctivagus Zone (lindstromi-prion-Iapetognathus Fauna) in western Newfoundland (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Nowlan and Williams2001). Terfelt et al. (Reference Terfelt, Bagnoli and Stouge2012) restudied the Global boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the base of the Ordovician System in the Green Point section, Newfoundland, Canada. They found I. fluctivagus is not present at the boundary interval. As a result, the identification of the Cambrian–Ordovician boundary level outside the GSSP section has proven to be problematic. Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Evens, Loch, Ethington, Stitt, Holmer and Popov2003, Reference Miller, Repetski, Nicoll, Nowlan and Ethington2014b) suggested the base of Iapetognathus Zone should be the Cambrian–Ordovician boundary level, i.e., the FAD of lowest species of Iapetognathus. In Hunan, I. jilinensis Nicoll et al., Reference Nicoll, Miller, Nowlan, Repetski and Ethington1999 is the lowest species of Iapetognathus. Consequently, the FAD of I. jilinensis is the base of the upper part of the C. lindstromi Zone and the Cambrian–Ordovician boundary level. Unfortunately, I. jilinensis has been found at only one level in Hunan, so this correlation is only approximate.

Cordylodus angulatus Zone (lower part).—

Cordylodus angulatus occurs in the C. angulatus Zone in Hunan and in the C. angulatus-Chosonodina herfurthi Zone in North China (Chen and Gong, Reference Chen and Gong1986), in the C. angulatus Zone in the western United States (Miller, Reference Miller1980, Reference Miller1988; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Hintze, Ethington, Miller, Taylor and Repetski1997; Nicoll et al., Reference Nicoll, Miller, Nowlan, Repetski and Ethington1999; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Evens, Loch, Ethington, Stitt, Holmer and Popov2003), and in the interval of the angulatus Fauna in western Newfoundland (Barnes, Reference Barnes1988; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Nowlan and Williams2001). It appears that the C. angulatus Zone in Hunan corresponds to the lower part of the zone in the regions mentioned, and the top of this zone is above the stratigraphic interval studied herein.

Correlation of conodont zones with trilobite zones

Many workers have investigated the trilobite biostratigraphy of Cambrian sections in Hunan, e.g., Lu (Reference Lu1956), Jegorova et al. (Reference Jegorova, Xiang, Lee, Nan and Kuo1963), Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Wang and Liu1966), Yang (Reference Yang1978, Reference Yang1981, Reference Yang1984), Lin (Reference Lin1991), Dong (Reference Dong1990a, Reference Dongb, 1991), Peng (Reference Peng1987, Reference Peng1992), Peng and Robison (Reference Peng and Robison2000), Peng et al. (Reference Peng, Babcock, Robison, Lin, Rees and Saltzman2004), Peng (Reference Peng2009a, Reference Pengb) and Peng et al. (Reference Peng, Babcock and Cooper2012). Peng (Reference Peng2009a, Reference Pengb) and Peng et al. (Reference Peng, Babcock and Cooper2012) presented a comprehensive summary with much new information that allows detailed correlation with the Cambrian conodont zones in Hunan (Fig. 6).

Conodont histology

Although histological study on conodonts can be traced back to the 1930s (Branson and Mehl, Reference Branson and Mehl1933), systematic histological investigations on conodonts began in the 1970s (Müller and Nogami, Reference Müller and Nogami1971) and since then has been carried out by many authors (Bengtson, Reference Bengtson1976, Reference Bengtson1983; Szaniawski, Reference Szaniawski1982, 1983, 1987; Andres, Reference Andres1988; Szaniawski and Bengtson, Reference Szaniawski and Bengtson1993, Reference Szaniawski and Bengtson1998; Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1998, etc.). The discovery of the entire conodont animal (Briggs et al., Reference Briggs, Clarkson and Aldridge1983; Aldridge, Reference Aldridge1987; Aldridge et al., Reference Aldridge, Briggs, Smith, Clarkson and Clark1993; Gabbott et al., Reference Gabbott, Aldridge and Theron1995) greatly stimulated the comparative histological study on euconodonts so as to verify their biological affinity, and many papers were involved in the “conodont controversies” (Purnell et al., Reference Purnell, Aldridge, Donoghue and Gabbot1995; Aldridge and Purnell, Reference Aldridge and Purnell1996; Donoghue et al., Reference Donoghue, Forey and Aldridge2000). In contrast to the debate, Szaniawski did refined work on the affinity of protoconodonts based on their hard tissues and the fossils of chaetognaths recognized in the Burgess Shale (Szaniawski, Reference Szaniawski2002, Reference Szaniawski2005). Philip C. J. Donoghue and Xi-ping Dong investigated well-preserved elements of protoconodonts, paraconodonts, and the earliest euconodonts from the middle and late Cambrian in the Paibi, Wangcun, and Wa’ergang sections in werstern Hunan. They found that conodont elements recovered from western Hunan are of great significance in terms of histology. Our comparative histological study on the earliest euconodonts has been published (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Donoghue and Repetski2005c; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Dong, Zeng and Zhao2005a, Reference Guo, Dong, Zeng and Zhaob), and the study on paraconodonts will be published in a separate paper.

Assignment of taxa to either protoconodonts, paraconodonts, or euconodonts is vitally important in the study of Cambrian conodonts. The present paper is only involved in the histological study as it relates to assigning taxa to one of those three groups. Bengtson (Reference Bengtson1976) proposed a model showing an evolutionary sequence from protoconodonts through paraconodonts to euconodonts. A direct evolutionary relationship between protoconodonts and paraconodonts remains unproved and is much more hypothetical than that between paraconodonts and euconodonts (Szaniawski and Bengtson, Reference Szaniawski and Bengtson1993; Donoghue et al., Reference Donoghue, Forey and Aldridge2000; Murdock et al., Reference Murdock, Dong, Repetski, Marone, Stampanon and Donoghue2013). At present, protoconodonts are assigned to phylum Chaetognatha Leuckart, Reference Leuckart1854, whereas paraconodonts and euconodonts are assigned to different classes of phylum Chordata Bateson, Reference Bateson1886 (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee, Miller and Jeong2009).

Histological investigations by Philip C. J. Donoghue and Xi-ping Dong (unpublished data) indicate that it is not always possible to distinguish reliably among the elements of these three taxonomic groups based only on study of their external morphology, even by experienced observers, and histological study is often required to determine the correct taxonomy. Paibiconus Dong, Reference Dong1993 and Huayuanodontus Dong and Bergström, 2001a were both considered originally to be protoconodonts (An and Mei, Reference An and Mei1994; Dong and Bergström, 2001a). Histological investigation by Philip C. J. Donoghue and Xi-ping Dong verified that Paibiconus is a protoconodont (Dong, Reference Dong2004). However, longitudinal cross sectioning of elements of Huayuanodontus showed a two-layered structure that is different from that of protoconodonts, paraconodonts, or euconodonts. Therefore, further histological work is needed to determine the taxonomic assignment of Huayuanodontus (cf. Dong, Reference Dong2007b). Coelocerodontus Ethington, Reference Ethington1959 has thin-walled coniform elements with large basal cavities. The cross section is extremely narrow. Clusters are very common. It has been referred to as a protoconodont, paraconodont, or euconodont by different authors (Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1991, p. 53). Müller and Hinz (Reference Müller and Hinz1991) considered it to be a euconodont, although they did not elucidate their histological evidence in 1991 or later (Müller and Hinz, Reference Müller and Hinz1998). Philip C. J. Donoghue and Xi-ping Dong tested many specimens of this genus recovered from Hunan by means of immersion in clove oil (unpublished data). Unequivocal crown material was found in all the tested specimens, so this genus should be considered as a euconodont.

Prooneotodus rotundatus is a cosmopolitan paraconodont species. Miller (Reference Miller1980) recognized a new genus and species that resembles P. rotundatus. He stated that the new genus and species differs from P. rotundatus in possessing a thin layer of apatite (crown material) that covers a massive white basal cone (Miller, Reference Miller1980, p. 32). Unfortunately, he has not performed any histological investigations that he mentioned would be needed to confirm his interpretation (personal communication, J.F. Miller, 2007). We investigated well-preserved elements that appear to be P. rotundatus from upper Cambrian strata in Hunan, South China by means of the oil immersion technique (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Donoghue and Repetski2005c). Some of the investigated elements show typical paraconodont strucure. However, some investigated elements have crown tissues, in which we found crystals of apatite perpendicular to the conodont grown axis, and regeneration could be observed at the apical portion of the elements. Both features are typical of euconodonts, and these elements are considered euconodonts rather than paraconodonts. Herein, they are assigned to Millerodontus intermedius n. gen. n. sp., and the species is interpreted as a transition between the paraconodont Prooneotodus and the primitive euconodont genus Proconodontus. Regenerated tips of elements are found also in Proconodontus, which occurs with Millerodontus. This is the first report to establish a new conodont genus in the light of histological study.

Post-Tremadocian conodonts are all euconodonts, but protoconodonts, paraconodonts, and euconodonts co-occur in Cambrian through Tremadocian strata. Therefore, histological investigation of Cambrian conodonts is of great importance not only in the differentiation of protoconodonts, paraconodonts, and euconodonts, but this information is the foundation on which to explore the taxonomy and the early evolution of conodonts.

Systematic paleontology

Recently, Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Lee, Miller and Jeong2009) separated the Cambrian and Tremadocian conodnts into three groups: paraconodonts, euconodonts, and protoconodonts in their Systematic Paleontology and proposed an updated classification of conodont faunas in terms of phylum, class, and order. We follow their taxonomic treatment herein.

Euconodonts

Phylum Chordata Bateson, Reference Bateson1886

Superclass Conodonta Pander, Reference Pander1856

Class Conodonti Branson, Reference Branson1938

Genus Coelocerodontus Ethington, Reference Ethington1959

Type species.—

Coelocerodontus trigonius Ethington, Reference Ethington1959.

Remarks.—

This genus consists of thin-walled coniform elements with large basal cavities. The cross section is extremely narrow. Clusters are very common. As mentioned above, histological investigation indicates that it is a euconodont. It is probably the oldest known euconodont.

Coelocerodontus bicostatus van Wamel, Reference van Wamel1974

Figures 7.1–7.12, 7.16–7.18, 8.1–8.4

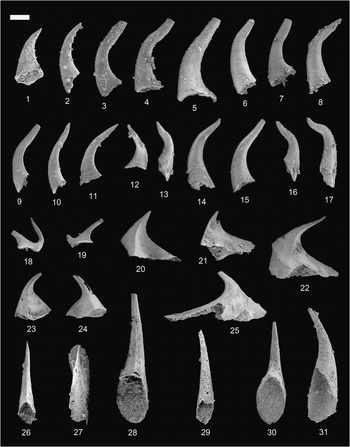

Figure 7 (1–12, 16–18) Coelocerodontus bicostatus van Wamel, Reference van Wamel1974; (1) Shenjiawan Formation, Wangcun section, GMPKU2399, lateral view; (2) Bitiao Formation, Wangcun section, GMPKU2400, lateral view; (3) Bitiao Formation, Wangcun section, GMPKU2401, lateral view; (4) Bitiao Formation, Wangcun section, GMPKU2402, lateral view; (5) Bitiao Formation, Wangcun section, GMPKU2403, lateral view; (6) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2404, lateral view; (7) Bitiao Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2405, lateral view; (8) Huaqiao Formation, Wangcun section, GMPKU2413, (9) Bitiao Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2406, lateral view; (10) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2407, lateral view; (11) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2408, lateral view; (12) Bitiao Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2409, lateral view; (16) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2410, lateral view; (17) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2411, lateral view; (18) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2412, lateral view; (13–15, 19–25) Coelocerodontus hunanensis n. sp.; (13) Shenjiawan Formation, Wangcun section, GMPKU2414, lateral view; (14) Shenjiawan Formation, Wangcun section, GMPKU2415, lateral view; (15) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2416, cluster; (19) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2417, lateral view; (20) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2418, lateral view; (21) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2419, lateral view; (22) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2420, lateral view; (23) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2421, lateral view; (24) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2422, lateral view; (25) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2423, lateral view. Relative scale bar represents 147 μm (1–11, 14, 16–25), 135 μm (12, 13, 15).

Figure 8 Conodont images using oil immersion techniques (Dong et al., 2005c) with Differential Interference Contrast (Nomarski) illumination. (1–4) Coelocerodontus bicostatus van Wamel, Reference van Wamel1974; (1) overview, GMPKU2254, showing the crown structure of euconodont; (2) close-up of (1); (3) overview, GMPKU2255, showing the crown structure of euconodont; (4) close-up of (3). Relative scale bar represents 109 μm (1, 3), 38 μm (2, 4).

1974Coelocerodontus bicostatus Reference van Wamelvan Wamel, p. 55, pl. 3, fig. 2.

1974Coelocerodontus latus Reference van Wamelvan Wamel, p. 56, pl. 1, fig. 2.

1983“Coelocerodontus” bicostatus van Wamel; Reference LandingLanding, p. 1172, fig. 10A, B.

1986Stenodontus compressus Reference Chen and GongChen and Gong, p. 186, pl. 24, figs. 11, 16, pl. 25, figs. 2–5, 7–13, 16, text-fig. 76.

1986Stenodontus jilinensis Reference Chen and GongChen and Gong, p. 187, pl. 18, figs. 2, 4–7, 9, 17, 18, pl. 19, figs. 3, 7, pl. 24, figs. 1, 9, 18, pl. 34, figs. 9, 14, 15, 19, text-fig. 77.

1987Coelocerodontus bicostatus van Wamel; Reference AnAn, p. 104, pl. 1, fig. 11.

1987Diaphanodus latus (van Wamel); Bagnoli et al., p. 155, pl. 2, figs. 11, 12.

1988Coelocerodontus cambricus (Nogami); Reference Heredia and BordonaroHeredia and Bordonaro, p. 190, pl. 2, figs. 2, 3.

1988Rotundoconus mendozanus Reference Heredia and BordonaroHeredia and Bordonaro, p. 194, pl. 3, fig. 5, pl. 4, fig. 3.

1988Coelocerodontus cambricus (Nogami); Reference Lee and LeeLee and Lee, pl. 1, fig. 27.

1988Coelocerodontus apparatus, Andres, pl. 9, figs. 3–8, text-fig. 19.

1991Coelocerodontus bicostatus van Wamel; Reference Müller and HinzMüller and Hinz, p. 53, pl. 41, figs. 1–21, text-figs. 20A–D.

2000“Proacontiodus” latus entis Reference Pyle and BarnesDubinina, p. 175, pl. 3, figs. 15, 16, 20, 21 (not figs. 1, 1a, 7, 8).

2000“Proacontiodus”latus Reference Pyle and BarnesDubinina, p. 174, pl. 3, figs. 30, 31.

2001Coelocerodontus cambricus (Nogami); Reference LeeLee, p. 449, figs. 6, 11.

2002aCoelocerodontus cambricus (Nogami); Reference LeeLee, p. 165, pl. 2, fig. 16.

2002bCoelocerodontus cambricus (Nogami); Reference LeeLee, p. 25, pl. 1, figs. 16, 17.

? 2006Coelocerodontus bicostatus van Wamel; Reference Qi, Bagnoli and WangQi et al., p. 187, pl. 3, fig. 17.

2007Coelocerodontus bicostatus van Wamel; Reference Landing, Westrop and KeppieLanding et al., p. 922, fig. 9a, b.

2009Coelocerodontus bicostatus van Wamel; Reference Lee, Lee, Miller and JeongLee et al., p. 423, figs. 7, 18.

2011Coelocerodontus bicostatus van Wamel; Reference Bagnoli and QiBagnoli and Qi, p. 12 (G, H, I).

2014Stenodontus compressus Chen and Gong; Reference Bagnoli and StougeBagnoli and Stouge, p. 20, fig. 11, N–R.

Description.—

Bimembrate apparatus of asymmetrical and subsymmetrical elements. The asymmetrical element is thin-walled and coniform. It is laterally compressed, with keeled anterior and posterior edges. Its cross section is extremely narrow. Both lateral sides have a costa that extends up to the apex. The pointed apex extends far beyond the posterior basal margin, leading to a recurved triangular outline in lateral view. The basal cavity is very deep. The subsymmetrical element differs from the asymmetrical element in the hook-like apical portion and the inconspicuous carinae instead of costae on both lateral sides.

Materials.—

469 specimens.

Occurrence.—

Known from the Wangcun and Wa’ergang sections, where it ranges from the Shandongodus priscus-Hunanognathus tricuspidatus Zone through the Cordylodus intermedius Zone.

Remarks.—

Müller and Hinz (Reference Müller and Hinz1991) described Morphotype alpha and Morphotype beta of this species. Of the material at hand, the asymmetrical element and subsymmetrical element correspond, respectively, with Morphotype alpha and Morphotype beta in terms of overall morphology.

Coelocerodontus hunanensis new species

Figures 7.13–7.15, 7.19–7.25, 9.1–9.14, 9.18, 9.19

Figure 9 (1–14, 18, 19) Coelocerodontus hunanensis n. sp.; (1) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2424, lateral view; (2) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2425, lateral view; (3) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2426, cluster, lateral view; (4) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2427, lateral view; (5) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2428, lateral view; (6) Shenjiawan Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2429, cluster, lateral view; (7) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2430, cluster, lateral view; (8) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2431, lateral view; (9) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, holotype, GMPKU2432, lateral view; (10) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2433, lateral view; (11) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2434, cluster, lateral view; (12) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2435, lateral view; (13) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2436, cluster, lateral view; (14) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2437, cluster, lateral view; (18) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2438, lateral view; (19) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2439, lateral view; (15, 17, 20, 22–24) Cordylodus angulatus Pander, Reference Pander1856; (15) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2440, lateral view; (17) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2441, lateral view; (20) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2442, lateral view; (22) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2169, lateral view; (23) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2170, lateral view; (24) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2171, lateral view; (16) Cordylodus proavus Müller, Reference Müller1959, Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2443, lateral view; (21, 25, 26) Cordylodus caseyi Druce and Jones, Reference Druce and Jones1971; (21) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2444, lateral view; (25) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2446, lateral view; (26) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2447, posterior view. Relative scale bar represents 158 μm (1, 2, 4–19, 22), 150 μm (3, 20, 21, 23–26).

Diagnosis.—

Elongate proclined, thin-walled coniform elements with very deep basal cavities, laterally compressed, with keeled anterior and posterior edges. Both lateral sides are characterized by costae or only one lateral side is characterized by a costa. The outline is extremely slender, with a high length/maximum width ratio.

Description.—

Elongate, thin-walled coniform elements, proclined, asymmetrical, laterally compressed, with keeled anterior and posterior edges. The cross section is extremely narrow. Both lateral sides are characterized by costae or only one lateral side is characterized by a costa, each of which extends up to the apex; position of these costae is highly variable. The outline of the element is extremely slender. The length/maximum width ratio is more than 3.5. The tip of the cusp is usually not preserved. The basal cavity is very deep.

Etymology.—

Named for its provenance in Hunan Province.

Types.—

Holotype: GMPKU2432, from the Cordylodus intermedius Zone, Furongian (upper Cambrian), Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, Wa’ergang village, Taoyuan County, Hunan Province.

Materials.—

368 specimens.

Occurrence.—

Known from Wangcun and Wa’ergang sections, where it ranges from the Proconodontus tenuiserratus Zone through the Cordylodus intermedius Zone.

Remarks.—

It differs from Coelocerodontus bicostatus in its much more slender outline and much higher length/maximum width ratio.

Genus Cordylodus Pander, Reference Pander1856

Type species.—

Cordylodus angulatus Pander, Reference Pander1856.

Remarks.—

Most species of this genus are cosmopolitan in distribution and are of great significance in biostratigraphy and the evolution of early euconodonts. There has never been a consensus on their apparatus reconstruction. Miller (Reference Miller1980) established a two-element apparatus of this genus, and he identified them as rounded and compressed elements based on the cross section of the cusp. This interpretation was accepted by some authors based on their own collections, e.g., An et al. (Reference An, Zhang, Xiang, Zhang, Xu, Zhang, Jiang, Yang, Lin, Cui and Yang1983), Chen and Gong (Reference Chen and Gong1986), and Dong (Reference Dong1987) (only Cordylodus proavus). Viira et al. (Reference Viira, Sergeeva and Popovu1987) recognized three element types of C. proavus, whereas Barnes (Reference Barnes1988) suggested four element types. Nicoll (Reference Nicoll1990) reinterpreted the apparatus reconstruction of this genus as a septimembrate apparatus containing M, S, and P elements. We still use the apparatus reconstruction by Miller (Reference Miller1980). Although this two-element model does not seem to be refined and updated, it is more practical than more complex models. Miller’s rounded element includes Nicoll’s S elements and probably Nicoll’s P elements, and Miller’s compressed elements correspond to Nicoll’s M elements.

Cordylodus angulatus Pander, Reference Pander1856

Figures 9.15, 9.17, 9.20, 9.22–9.24, 10.1, 10.2

Figure 10 Conodont images using oil immersion techniques (Dong et al., 2005c) with Differential Interference Contrast (Nomarski) illumination, showing the shapes of basal cavities. (1, 2) Cordylodus angulatus Pander, Reference Pander1856; (1) the same specimen as Figure 9.17; (2) the same specimen as Figure 9.20; (3–6) Cordylodus intermedius Furnish, Reference Furnish1938; (3) the same specimen as Figure 12.1; (4) the same specimen as Figure 12.2; (5) the same specimen as Figure 12.3; (6) the same specimen as Figure 12.7. Relative scale bar represents 167 μm (1), 109 μm (2, 5), 103 μm (3, 4, 6).

1856Cordylodus angulatus Reference PanderPander, p. 33, pl. 2, figs. 28–31, pl. 3, fig. 10.

1856Cordylodus rotundatus Reference PanderPander, p. 33, pl. 2, figs. 32, 33.

1938Cordylodus subangulatus Reference FurnishFurnish, p. 338, text-fig. 2D, pl. 42, fig. 3.

1955Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference LindströmLindström, p. 551, pl. 5, fig. 9, text-fig. 3 (G).

1955Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference LindströmLindström, p. 553, pl. 5, figs. 17–20, text-fig. 3 (F).

1971Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Druce and JonesDruce and Jones, p. 66, pl. 3, figs. 4–6, text-figs. 23a, b.

1971Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference Druce and JonesDruce and Jones, p. 71, text-figs. 23t, pl. 3, figs. 8–10.

1971Cordylodus sp. A Reference Druce and JonesDruce and Jones, p. 72, text-fig. 23u, pl. 8, fig. 10a, b.

1971Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference Ethington and ClarkEthington and Clark, pl. 1, fig. 17.

1971Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Ethington and ClarkEthington and Clark, pl. 1, 15, 16, 20.

1973Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference MüllerMüller, p. 27, pl. 11, figs. 1–7, text-fig. 2G.

1973Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference MüllerMüller, p. 36, text-figs. 2H, 10a, b, pl. 11, figs. 8–10.

1974Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference van Wamelvan Wamel, pl. 1, fig. 14.

1980Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference MillerMiller, p. 13, pl. 1, figs. 22, text-fig. 4Q.

1980Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference MillerMiller, p. 20–21, pl. 1, fig. 24, text-fig. 4p.

1981Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference AnAn, pl. 2, fig. 17.

1981Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference AnAn, pl. 1, figs. 18–19.

1982Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference RepetskiRepetski, p. 16, pl. 4, fig. 9, text-fig. 4 (L).

1982Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference RepetskiRepetski, p. 18, pl. 5, fig. 3, text-fig. 4 (N).

1983Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference An, Zhang, Xiang, Zhang, Xu, Zhang, Jiang, Yang, Lin, Cui and YangAn et al., p. 84, pl. 8, figs. 1, 2.

1983Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference An, Zhang, Xiang, Zhang, Xu, Zhang, Jiang, Yang, Lin, Cui and YangAn et al., p. 88–89, pl. 8, figs. 3–7.

1985Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference NowlanNowlan, p. 111, text-fig. 4 (3).

1985Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference WangWang, p. 215, pl. 1, figs. 1–3, pl. 7, figs. 11–14, pl. 10, figs. 17 (not 15), pl. 11, figs. 17, 18 (?), pl. 12, figs. 18 (?), 19, 20 (?), pl. 14, fig. 7 (not 8) (part).

1985Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference WangWang, p. 219, pl. 1, fig. 5, pl. 7, figs. 25, 26; pl. 11, fig. 22.

1985Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference DongDong, p. 394, pl. 1, fig. 6, pl. 3, fig. 5, text-fig. 1 (J).

1985Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference DongDong, p. 396, pl. 2, fig. 8, pl. 3, fig. 9, text-fig. 1L.

1986Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Chen and GongChen and Gong, p. 125, pl. 34, figs. 2–4, text-fig. 36.

1986Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference Chen and GongChen and Gong, p. 133, pl. 37, figs. 3, 8, 18, text-fig. 41.

1987Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference DongDong, p. 153, pl. 1, figs. 17, 18, 22, text-figs. 3H, J, 4F.

1987Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference DongDong, p. 155, pl. 1, fig. 20 only (not 23), text-fig. 3I only (not K).

1990Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference NicollNicoll, figs. 3 (4b–c only), 5 (3a–4c only), 12.

1994Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Ji and BarnesJi and Barnes, p. 31, pl. 5, figs. 1–9.

1994Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Wright and CooperWright and Cooper, p. 471, fig. 17B.

1996Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Lee, Lee and KoLee et al., p. 99, pl. 2, fig. 1.

1998Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Rao and TortelloRao and Tortello, p. 43, pl. 1, figs. 1, 2, 3, 6.

2000Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Zhao, Zhang and XiaoZhao et al., p. 194, pl. 37, figs. 13, 14, 16, 17.

2000Cordylodus rotundatus Pander; Reference Zhao, Zhang and XiaoZhao et al., p. 194, pl. 37, figs. 7–12.

2001Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Pyle and BarnesPyle and Barnes, p. 1397, pl. 1, figs. 3, 4.

2002Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Pyle and BarnesPyle and Barnes, p. 177, pl. 4, figs. 1–3.

2003Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Heinsalu, Kaljo, Kurvits and ViiraHeinsalu et al., p. 147, text-fig. 5, 24 (only).

2004cCordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Dong, Donoghue, Cheng and LiuDong et al., p. 1201, pl. 2, figs. 17, 28, 30, pl. 4, figs. 4, 6, 12, 14.

2005Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Ortega and AlbanesiOrtega and Albanesi, p. 365, fig. 5 (14).

2007Cordylodus angulatus Pander; Reference Pyle, Barnes and McanallyPyle et al., p. 1735, fig. 11.8, 11.9.

Description.—

Bimembrate apparatus of rounded and compressed elements. Rounded element with cusp and denticles rounded or oval in cross section and composed mostly of white matter. Basal cavity shallow to moderately deep, usually extending not higher than top of posterior denticulate process. Anterior edge of basal cavity strongly concave and tip recurved. Anterobasal margin slightly rounded to well rounded. Posterior process without carina or with a carina on one side. Compressed element symmetrical or subsymmetrical, with long posterior denticulate process. Cusp and denticles compressed laterally with sharp edges. Basal cavity shallow to moderately deep. Anterior edge of basal cavity slightly concave.

Materials.—

12 specimens.

Occurrence.—

Known from the Wa’ergang section, where it occurs in the Cordylodus angulatus Zone (lower part).

Remarks.—

Miller (Reference Miller1980) suggested that the two form-species Cordylodus angulatus and Cordylodus rotundatus belong to two multielement species mainly based on the minor differences between them. However, many conodont workers considered the two form-species to be a single apparatus, because the two form-species commonly occur together. Based on the common association of the two form-species recovered from Hunan, we follow the opinion of the majority.

Cordylodus caseyi Druce and Jones, Reference Druce and Jones1971

Figures 9.21, 9.25, 9.26, 11.4

Figure 11 (1–3, 5–27) Cordylodus intermedius Furnish, Reference Furnish1938; (1) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2452, lateral view; (2) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2453, lateral view; (3) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2454, lateral view; (5) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2455, lateral view; (6) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2456, lateral view; (7) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2457, lateral view; (8) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2458, lateral view; (9) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2459, lateral view; (10) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2460, lateral view; (11) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2461, lateral view; (12) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2462, lateral view; (13) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2463, lateral view; (14) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2464, lateral view; (15) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2465, lateral view; (16) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2466, lateral view; (17) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2467, lateral view; (18) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2468, lateral view; (19) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2469, lateral view; (20) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2470, lateral view; (21) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2471, lateral view; (22) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2472, lateral view; (23) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2473, lateral view; (24) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2474, lateral view; (25) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2475, lateral view; (26) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2476, lateral view; (27) Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2477, lateral view; (4), Cordylodus caseyi Druce and Jones, Reference Druce and Jones1971; Panjiazui Formation, Wa’ergang section, GMPKU2451, lateral view. Relative scale bar represents 180 μm (1–21, 24–27), 145 μm (22), 154 μm (23).

1971Cordylodus caseyi Reference Druce and JonesDruce and Jones, p. 67, pl. 2, figs. 9–12, text-figs. 23d, e.

1990Cordylodus caseyi Druce and Jones; Reference NicollNicoll, p. 543, figs. 3 (3b), 13 (4a–5c), 14 (1–2) only.

1993Cordylodus caseyi Druce and Jones; Reference LandingLanding, p. 14, fig. 8, 3–13, p. 15, fig. 9, 1–11.