Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected men and women in systematically different ways, with potential long-term implications for gender equality (Alon et al. Reference Alon, Doepke, Olmstead-Rumsey and Tertilt2020). In the United States and elsewhere, social distancing measures coupled with school and daycare closures took away many parents’ options to outsource childcare, a task disproportionately performed by women under traditionally gendered household arrangements. Footnote 1 How did working parents weather this shock?

As access to safe and affordable childcare became uncertain Footnote 2 , working parents were faced with having to renegotiate their household arrangements. Lewis (Reference Lewis2020) describes the pandemic as a “disaster for feminism” as it “smashes up the bargain that so many dual-earner couples have made in the developed world: We can both work, because someone else is looking after our children. Instead, couples will have to decide which one of them takes the hit.” However, it may also be an opportunity to renegotiate toward more gender-balanced arrangements (Seiz Reference Seiz2020). Indeed, evidence from across contexts shows that men increased their contributions to care work during the pandemic (Oxfam International 2020). However, women continued to shoulder the larger burden in many cases, leaving inequalities unchanged or even exacerbated.

In the United States, the pandemic has had deleterious effects on women’s labor force participation. Between February and April 2020, mothers with young children had reduced their work hours four to five times more than fathers (Collins et al. Reference Collins2021) and were more likely to have exited the labor force altogether (Landivar et al. Reference Landivar, Ruppanner, Scarborough and Collins2020); mothers working from home in April – May 2020 spent more time on housework than fathers (Lyttelton et al. Reference Lyttelton, Zang and Musick2021); in September 2020, four times as many women as men dropped out of the labor force (Kashen, Glynn and Novello Reference Kashen, Glynn and Novello2020). Even as jobs return, women – and Black and Latina women in particular – remain excluded from the recovery (Ewing-Nelson Reference Ewing-Nelson2021; Lim and Zabek Reference Lim and Zabek2021). The wins of the gender revolution of the 1960s, already stalled and uneven (England Reference England2010), now stand threatened.

In this study, we seek to understand how one aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic – the shock to the availability of childcare – shapes American parents’ preferences over how to divide work inside and outside the home. What arrangements are considered “fair” under a situation of unusual strain on the usual options? Understanding these micro-dynamics can help make sense of the visibly gendered impacts of the pandemic.

To answer this question, we conducted a conjoint survey experiment with an online sample of nearly 2000 parents in the USA during August 2020. Respondents were shown vignettes depicting different household arrangements, asked to choose which arrangement they would personally prefer to be in and to rate the perceived fairness of each. Each vignette describes the situation of a heterosexual married couple with two children and has five randomly varied attributes: the availability of childcare, the wife’s work status and income, the husband’s work status and income, how they divide time spent on household chores, and the frequency with which the husband contributes to traditionally “feminine” chores. The conjoint design allows us to estimate how each of these features affects parents’ preferences and fairness perceptions, and how sensitive these preferences are to childcare availability.

Unsurprisingly, we first document that men and women prefer situations where options for childcare are available and deem situations where it is unavailable as relatively unfair, all else equal. However, contrary to our expectations, we find that the unavailability of childcare, in the context of our experimental vignettes, does not change how parents weigh other aspects of household arrangements. We take this as suggestive evidence of the persistence of preferences over other aspects of household arrangements in face of a shock to childcare availability: a key feature of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given overwhelming evidence that women continue to shoulder the disproportionate burden of childcare in the United States, we expected that they may value the availability of childcare options more highly than men. However, we do not find a gender gap in preferences over childcare availability.

Second, we document a gendered pattern in respondents’ evaluations of income and employment. While respondents strictly prefer situations where the husband or wife is employed and earning to those where they are unemployed, this employment and earned income is not valued equally. Both men and women respondents’ preferences are more sensitive to husband’s earnings than those of wives. American parents in our sample value equal dollar amounts less when earned by wives. Moreover, in line with existing scholarship around the gendered stigma of unemployment, situations where men are unemployed are far less preferable than those where women are unemployed. Notably, women respondents evaluate situations where the husband is unemployed even more negatively than men do.

Third, we document a gendered asymmetry in preferences for equality within the home. On the one hand, both men and women respondents overall prefer – and perceive as more fair – situations where husbands and wives spend equal times on housework, and where husbands contribute to traditionally feminine tasks of cooking, cleaning, and housework relative to unequal divisions. However, women respondents value equal time spent on housework and husbands’ regular contributions to feminine tasks more highly than their male counterparts.

Our study provides timely evidence on individual preferences and perceptions of fairness over household arrangements at a moment where such arrangements are subject to renegotiation. These preferences also have potential relevance for distributive policy outcomes. Individuals’ perceived fairness of socioeconomic circumstances is shown to have a direct line to public support for re-distributive government programs (Alesina and Angeletos Reference Alesina and Angeletos2005; Krimmel and Rader Reference Krimmel and Rader2021). The perceived fairness of different aspects of household arrangements may similarly have implications for whether the US government will face pressure to reform its social safety net.

Additionally, our findings help illuminate the micro-foundations of women’s labor force participation in the United States and the hit it has taken during the pandemic. Persistent gender wage gaps, occupational segregation, coupled with a particular lack of childcare support relative to other high-income countries mean that most married American women earn less than their male partners (Blau and Kahn Reference Blau and Kahn2013). For dual-earner households, this may make mothers’ retreat from the labor market relatively less costly in terms of income loss than that of their husbands. However, a purely income-based explanation is incomplete: a rich literature in political economy and sociology establishes how the symbolic value of employment and income is deeply gendered, and how the ubiquity of “male breadwinner norms” shape women’s labor market outcomes (Bertrand, Kamenica and Pan Reference Bertrand, Kamenica and Pan2015; England Reference England2010; Gonalons-Pons and Gangl Reference Gonalons-Pons and Gangl2021; Iversen and Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006; Rao Reference Rao2020). Our study contributes to this understanding: men and women in our sample simply attach a lower value to the same dollar amount of income when it is earned by a wife than a husband, and this is more pronounced among women respondents. Our findings confirm the persistence of these gendered norms during the pandemic in the United States.

Theoretical framework

Despite having made major strides in labor force participation, women in the USA continue to perform the “lion’s share” of household labor (Lachance-Grzela and Bouchard Reference Lachance-Grzela and Bouchard2010). This situation of persisting inequality within the home is reinforced both by individually held attitudes about how household labor should be divided Footnote 3 and the unique policy environment of the USA in which individuals make these choices. In this section, we discuss theoretical predictions around how a set of individual-level factors and structural conditions shape heterosexual individuals’ preferences over household arrangements and how far they perceive different arrangements to be. We are interested in how the specific constraint of childcare availability during the COVID-19 pandemic may shape these preferences. Our predictions, and in line with this, our sample of respondents do not extend to individuals in same-sex partnerships, which differ in fundamental ways with regard to the gendered dynamics of their household arrangements (Brewster Reference Brewster2017; Solomon, Rothblum, and Balsam Reference Solomon, Rothblum and Balsam2005).

Childcare availability and COVID-19

Families’ access to childcare for young children encompasses a set of options, including care provided through facilities like day-cares and childcare centers, and the de-facto care provided through in-person schooling. It may also include care provided by other family members such as grandparents or hired help such as nannies and babysitters. American parents’ limited access to affordable care is a longstanding structural problem. School and daycare closures alongside social distancing guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic further limited access to all of these options to varying degrees and pushed the childcare crisis to a brink. Footnote 4

Findings from political science, economics, and sociology provide crucial insight into how structural constraints and institutional environments shape the decisions that families make. Iversen and Rosenbluth (Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth.2010) find that women’s propensity to take on the “second shift” at home is determined by their bargaining power within the household, which is in turn shaped by a set of macro-level variables including the legal ease of divorce, the size of the public sector, and availability of part-time employment. Pedulla and Thebaud (Reference Pedulla and Thébaud2015) find that when individuals are randomly primed with information about low institutional constraints (supportive workplace policy), they are more likely to prefer an egalitarian relationship model. The sudden removal of the means of outsourcing the traditionally feminine task of childcare represents a potent shift in the institutional environment. For the past half-century, the bargain that couples strike on who does what in the home and the labor market has been based on the availability of childcare and in-person schooling. It is an open question as to what will happen to gender equity in the home, labor market, and in politics when this key institutional feature is abruptly altered, or when states decide to “re-open” the economy even as childcare facilities remain closed.

We predict that access of childcare will condition individuals’ preferences over different household arrangements and that this effect will be stronger for some: namely women, who perform most of this care work, and those who hold gender-equitable attitudes.

The conjoint experiment also allows us to test the extent to which individuals value the availability of outside options for childcare relative to other factors such as couples’ earnings. Moreover, we are able to test whether the unavailability of such options in the context of our experimental vignettes shapes individuals’ valuation of egalitarian divisions of labor and men’s contribution to traditionally feminine tasks.

Division of household labor

Despite persisting gender inequality in the actual division of household labor, there is also a documented preference for more equitable and egalitarian distributions as the “ideal” Gerson (Reference Gerson2010); Nordenmark and Nyman (Reference Nordenmark and Nyman2003); Pedulla and Thebaud (Reference Pedulla and Thébaud2015). We thus expect that individuals will on average prefer an equitable division of time spent on household chores by male and female partners in a couple, relative to inequitable divisions where either the male or female partner spends more time.

While men’s time spent on housework has been increasing steadily since the 1960s in the USA, Footnote 5 the composition of tasks that men and women spend time on remains gendered. Footnote 6 Importantly, the composition of household tasks performed by each partner seems to matter for whether individuals perceive an arrangement as “fair.” Blair and Johnson (Reference Blair and Johnson1992) find that men’s contribution to “female-dominated tasks” such as meal preparation and cleaning is an important predictor of their wives’ perception of fairness. However, men’s contribution to “male-dominated” or gender-neutral tasks, such as yardwork, does not show a similar relationship. We thus expect that all else equal, individuals will prefer a situation where the male partner contributes to “feminine” tasks and that this preference will be stronger among women and among individuals who hold gender egalitarian views.

Work and earning status

A joint household income maximizing perspective suggests that individuals should prefer situations where male and female partners in a couple earn greater amounts and household income is maximized. However, earning status may also shape preferences over types of household arrangements. For instance, within-couple disparities in earnings and assets may prompt the relatively deprived partner to consider inequitable contributions to household tasks as “fair.” In a study of couples in the United States, Lennon and Rosenfield (Reference Lennon and Rosenfield1994) find that when accounting for actual time-use, women who have more economic options outside of marriage are more likely to view the inequitable division of labor in their own households as unfair: earning and resources thus shape perceptions of fairness. This implies that the gap in men and women’s earning status within a couple may condition the effect of other factors (like time-use) on preferences and perceptions. In this study, while we do not interrogate predictions about these conditional effects, we simply test the prediction that on average individuals will prefer arrangements that maximize household income.

Gender ideology

We expect that individual’s predispositions toward gender equality will shape their preferences for gender-equitable arrangements in a household. Moreover, we expect that gender ideology will shape how individuals make subjective assessments about the fairness of objective distributions of household labor. We operationalize “gender ideology” using a subset of the Modern Sexism Scale, which is used in the American National Election Studies (ANES). Footnote 7 Existing evidence suggests that in heterosexual couples, the female partner’s gender ideology is particularly influential in determining the relationship between marital satisfaction, perceptions of fairness, and the division of labor in the home (Greenstein Reference Greenstein1996a, Reference Greenstein1996b; Lavee and Katz Reference Lavee and Katz2002; Lee Reference Lee2002). Footnote 8 We expect those who score lower than the median within our sample on the sexism scale to have relatively stronger preferences for arrangements with a gender-equitable division of household labor and for arrangements where men contribute to traditionally feminine tasks. One caveat to this prediction is that measuring gender ideology and sexist attitudes in a survey context prior to asking respondents to state preferences over different household arrangements may “prime” these attitudes and make them especially salient to the choice. We would therefore interpret any estimated effects of these attitudes, measured as such, on stated preferences as being an upper bound of the potential effects.

Testable predictions

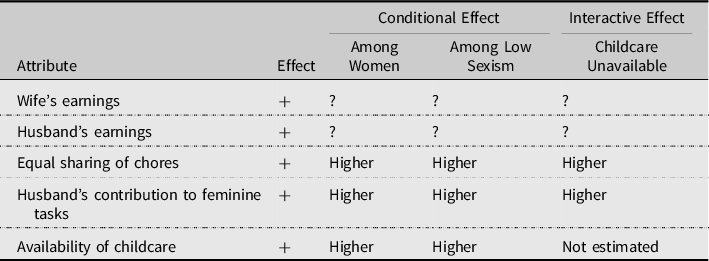

The design of our conjoint experiment study reflects the above set of factors that can be expected to affect individuals’ preferences over household arrangements and their perceived sense of fairness of these arrangements. Table 1 describes the attributes and levels included in the experiment; Table 2 summarizes our predictions about (1) the direction of the average marginal component effect of each of these factors on respondents’ preferences; (2) the conditional effect among subgroups of interest; and (3) the effect of randomized attributes in situations where childcare is unavailable. While we expect that the unavailability of childcare will have interactive effects with gender given strong evidence that women are likely to bear the brunt of additional childcare in the absence of outside options, we do not estimate these interactions as we are pessimistic about power for this analysis. Footnote 9

Table 1 Attributes and Values for Conjoint Profile Vignette

Table 2 Hypotheses of Average, Conditional, and Interactive Effects of Attributes on Respondents’ Personally Preferred Situation and Perceptions of Fairness

NOTES : “+” in Column 2 indicates expectation of a positive effect; “higher” in Column 3 indicates that we expect the size of the effect to be larger among women than men; “higher” in Column 4 indicates that we expect the size of the effect to be larger among individuals who score low on the sexism scale relative to those who score high; “higher” in Column 5 indicates that we expect the size of the effect of to be larger when childcare is unavailable. “?” indicates that we are agnostic about the direction of the effect but will estimate it.

Study context and design

We use a paired vignette conjoint experiment fielded online in the USA to test the predictions laid out in the prior section. The USA is the only OECD country that does not mandate paid family leave for new parents; it also lags behind the OECD average for public expenditure on early childhood and educational care as a proportion of country GDP (Olivetti and Petrongolo Reference Olivetti and Petrongolo2017). England (Reference England2010) describes the lack of family-friendly policies in the USA following terms: “One form the devaluation of traditionally female activities takes is the failure to treat child rearing as a public good and support those who do it with state payments.” The exacerbated crisis of child care during the COVID-19 pandemic may also be a tipping point: issues of childcare and the division of labor within the home achieved prominence on the national political stage during this time.

Our experiment was administered as part of an online survey conducted on the Qualtrics platform with 1,938 respondents recruited through the Lucid Marketplace on August 19 – 23rd, 2020. The survey was targeted to adults aged 18–45 in heterosexual partnerships with at least one child under the age of 12. Footnote 10 The characteristics of the target sample were intended to closely mirror the characteristics of the couple described in the hypothetical profiles in the conjoint experiment. Summary statistics of key background characteristics of our sample are provided in supplementary materials.

Upon consenting to participation, recruited respondents answered a set of background questions, followed by the conjoint experiment. Table 1 details the 5 attributes and the possible values that each attribute could take (either 2 or 3). Respondents were presented with four pairs of hypothetical vignettes, thus completing four “choice tasks.” Vignettes were presented side by side, with each pair displayed on a separate screen. The attributes were presented in a randomized order that was fixed across the 4 pairings for each respondent to “ease the cognitive burden for respondents while also minimizing primacy and recency effects” Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). A sample vignette is reproduced below:

Sue and Jim have two young children. She is currently [not working a job/working a job and earning 50 k/working a job and earning 100 k] . He is currently [not working a job/working a job and earning 50 k/working a job and earning 100 k] . She spends [much more/about the same/much less] time than him on household chores and childcare in the home. He [rarely/sometimes/regularly] pitches in with the cooking, cleaning and childcare. The couple has determined that there are [no/at least one] childcare options available in the coming months.

After viewing each pair of profiles, respondents answered three questions that serve as the primary outcome measures for the study. They were first asked to choose which situation they would personally prefer to be in themselves (Outcome 1) and then to rank the perceived fairness of each profile on a 5-point scale (Outcome 2). The first outcome, which is a forced choice, allows us to assess the effect of each attribute value in the evaluation of one profile relative to another. The second outcome, which is measured separately for each profile, allows us to evaluate the perception of fairness of each profile (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014).

We registered the design of the study and hypotheses with the EGAP registry prior to the collection of any survey data (Registration ID: 20200819AA). A copy of the registration which includes a pre-analysis plan is available at: https://osf.io/aq9dv.

Findings

This section presents the results from the pre-specified analysis for our conjoint experiment.

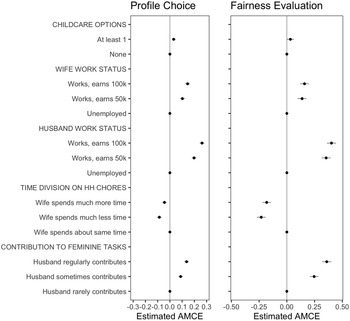

Figure 1 shows the main AMCE results for the two outcome variables (probability of choosing a given profile and perceived fairness of a profile). We find, in line with our prediction, that all else equal, respondents prefer household arrangements with least 1 option for childcare. However, the magnitude of the effect of childcare availability, relative to that of other attributes, is quite small. To illustrate, the effect of the male partner in a couple earning 100 k (relative to being unemployed) is nearly 10x greater. In fact, male earnings are the attribute with the largest effect on respondent preferences, and these effects are also large relative to those of the female partners’ earnings. A respondent is 20% more likely to choose a situation where the husband earns 50 k a year (relative to not working); the effect of a wife earning 50 k a year (relative to not working) is half that: 10%. With regard to the division of household labor, a clear preference for an equal gender division of time spent on household chores emerges. Situations where the wife spends much less (or much more) time than the husband on housework are less preferable to those where the times spent are equal. However, respondents prefer situations where women spend more time relative to those where women spend less time than husbands. Equality may be preferable to inequality, but an unequal burden borne by women is still preferable to one borne by men. However, men’s contribution to “feminine-coded” tasks has large effects, comparable in size to those of women’s earnings.

Figure 1 Conjoint Analysis Results: AMCE, OLS Regression.

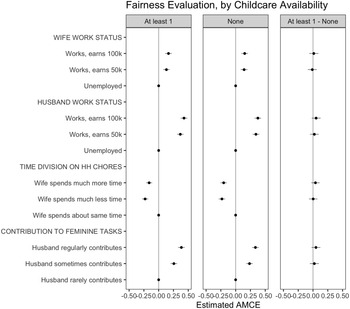

Our findings on fairness evaluation follow largely similar pattern. However, some informative differences emerge. While the effect of the childcare availability attribute on respondents’ preference for a situation is positive and statistically significant, it is smaller in magnitude and barely significant in the case of fairness evaluations. While respondents perceive unequal time spent on household chores to be less fair, in this case a wife spending “much less” or “much more” time is seen as equally unfair. Taken together with the previous results on preferred situations, this points toward a possibility of divergence between fairness perception and preferences in some domains: respondents rate women spending much more or much less time on household chores as similarly unfair situations, but when forced to choose, prefer the former.

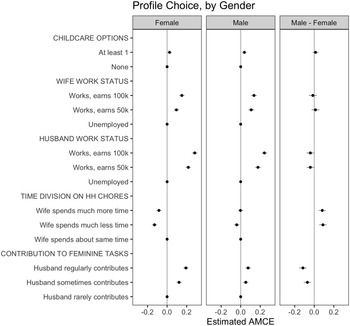

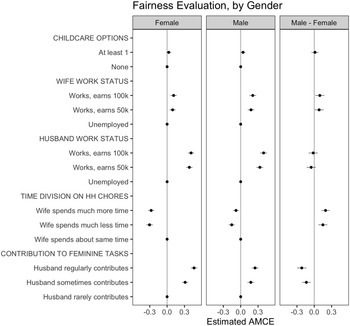

Figures 2 and 3 show the AMCE results, conditional upon a respondent’s self-identified gender. We do not find significant differences in the effect of the childcare availability attribute on men and women’s evaluations. The effect of time division shows a stark gendered pattern. Women are equally averse to situations where wives spend more or less time than their husbands on household chores. While men have a preference for equal division relative to a situation where the wife spends less time, they are in fact indifferent between an equal division and a situation where a woman does more, even though they see these situations as similarly less fair relative to equal divisions. The effect of husband’s contributions to feminine tasks is much larger for women than it is for men both when it comes to preferences and fairness evaluations; moreover, the jump in this effect from husbands contributing “sometimes” to “regularly” is large and significant for women, but insignificant for men. There is also an interesting result on the effects of earnings by the male and female partner on men and women’s likelihood of choosing a profile. Firstly, the effect of men’s earnings is simply larger than that of women’s earnings, as in the pooled results. In the case of the male partner’s earnings, both men and women are significantly more likely to prefer a situation where the man earns 100 k relative to when he earns 50 k. However, when it comes to the female partner’s earnings, the effect of 100 k is significantly greater than that of earning 50 k among women, but this difference is not significantly different among male respondents. That is, in situations where a female partner is working, male respondents seem to be indifferent between a situation where she earns 50 k vs. 100 k.

Figure 2 Conjoint Analysis Results: AMCE, OLS Regression.

Figure 3 Conjoint Analysis Results: AMCE, OLS Regression.

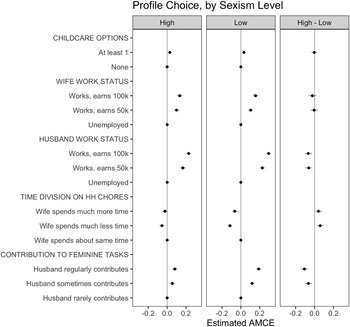

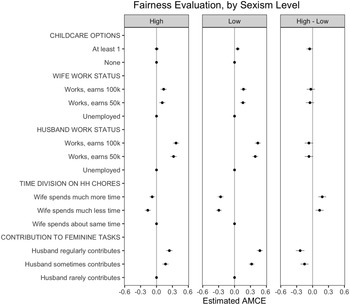

Figures 4 and 5 show the AMCE results, conditional upon a respondent’s self-identified gender ideology. This measure is based on responses to four attitudinal questions from the Modern Sexism Scale. The responses are scored on a 0–4 scale where a respondent receives a score of 4 if they strongly agree with a sexist statement, and 0 if they strongly disagree. The scores for 4 such statements are summed and we use the median of this summed quantity to categorize respondents into “High Sexism” vs. “Low Sexism.” The differences in effects by this measure of sexism emerge in the household time division and men’s contribution to feminine tasks attributes. The negative effect of unequal situations where women spend less time than men on household chores is higher among those who score low on the sexism scale, and this is especially pronounced in the case of fairness perceptions. The effect of men’s contributions to feminine-coded tasks on both preferences for a situation and perceived fairness is substantially larger for those who score lower than median on the sexism scale.

Figure 4 Conjoint Analysis Results: Conditional AMCE, OLS Regression.

Figure 5 Conjoint Analysis Results: Conditional AMCE, OLS Regression.

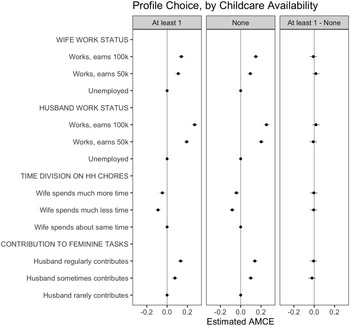

Figures 6 and 7 show the ACIE results, the effects of randomly varied attributes in the profile conditional upon the childcare availability attribute. We do not find evidence that the factors interact with childcare availability. We cannot reject the null hypotheses that these attributes have similar effects on respondent’s preferred situation or their evaluation of fairness of other attributes.

Figure 6 Conjoint Analysis Results: ACIE, OLS Regression.

Figure 7 Conjoint Analysis Results: ACIE, OLS Regression.

We interpret this as suggestive evidence that a “shock” to childcare availability like the one that so many have experienced in the past few months may not shift underlying preferences over the gendered division of labor or the value attached to male and female partners’ incomes. On the one hand, this is a positive story: in the context of our experiment, when childcare is unavailable, respondents continue to prefer (and perceive as fair) arrangements where wives and husbands spend equal times on housework to situations where wives spend much more (or much less) time; where husbands contribute to feminine-coded tasks sometimes or regularly (relative to rarely). On the other hand, we also do not find evidence for a dramatic change in preferences toward more equal sharing of burdens of household chores and care. When childcare is unavailable in the context of our experiment, and there is an objectively larger load to be shared, men and women do not place higher value on men’s contribution to household tasks; nor does the situation where a woman spends “much more time than” a man on these tasks become less acceptable. This lack of change may help understand some of the descriptive patterns emerging on the division of household labor during the pandemic: men may be taking on a greater volume of chores and care work than before, but not large enough to actually skew the division toward a more equal situation. This, coupled with the higher value placed on men’s earnings, has stark implications for women’s participation in the labor force.

Discussion

It is clear that the ongoing pandemic will have effects on gender equity within the home, in the labor market, and in the political sphere. The pandemic has also served to highlight the centrality of the home, and power contestations within it, for labor market outcomes (Kabeer et al. Reference Kabeer, Razavi and van der Meulen Rodgers2021). The political implications of women’s observed retrenchment from the labor force during this time cannot be overstated: women’s labor force participation is strongly associated with the formation of distinctive policy preferences and voting patterns and political participation (Andersen and Cook Reference Andersen and Cook1985; Iversen and Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth.2010, Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2008; Schlozman, Burns and Verba Reference Schlozman, Burns and Verba1999; Togeby Reference Togeby1994). The personal choices that households make about the division of labor within and outside the home may thus have serious political ramifications down the line.

Our study provides evidence on the gendered preferences that underlie these choices and also points to the prospects for change toward more gender-equitable outcomes. On the one hand, the importance of better childcare support and family-friendly policy is clear and urgent, particularly in light of the US’ laggard status on this front. Yet, our findings show that while men and women may agree on the importance of having access to options for childcare, they also seem to undervalue mothers’ labor force participation and earnings vis-a-vis that of fathers, and men continue to value equitable divisions of household labor less than women do. Having access to outside options for childcare, at least in the context of our conjoint experiment, does not shift these evaluations. While this certainly does not rule out the possibility of family-friendly social policy shifting gendered norms and preferences around work and household labor in the longer term, it does suggest the need to take these underlying preferences seriously. As Htun (Reference Htun2022) notes: “Without explicit attention to cultural associations surrounding reproductive labor, there is a risk that progressive policy changes will produce only a limited effect on structures of inequality.”

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2022.24

Data availability statement

The data, code, and any additional materials required to replicate all analyses in this article are available at the Journal of Experimental Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/E6J9AS The pre-registration is available at: https://osf.io/aq9dv

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding for this study from The Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale University. We thank Alexander Coppock, participants at the EGEN 2020 Junior Faculty Workshop, the journal editors, and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful feedback and comments.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement

The study design received conceptual approval from the Yale University COVID-19 Research Oversight Committee, was deemed exempt by the Yale University IRB (Protocol ID: 2000028351), and adheres to APSA’s Principles and Guidance for Human Subjects Research. Detail on the experimental procedures is included in Section A of the Supplementary Materials.