Under unfavourable conditions, proteins can fold and aggregate abnormally, which can lead to the formation of amyloids. The monomeric protein macromolecules in amyloid fibrils are non-covalently bonded (Arnaudov and De Vries, Reference Arnaudov and De Vries2005) and the resulting structures are rich in β-sheets (Sunde et al., Reference Sunde, Serpell, Bartlam, Fraser, Pepys and Blake1997). The presence of amyloids in the human body is associated with serious diseases including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and spongiform encephalopathies (Chiti and Dobson, Reference Chiti and Dobson2006). Amyloidogenesis appears to be universal process which results from an intrinsic property of the polypeptide chain (Chiti et al., Reference Chiti, Webster, Taddei, Clark, Stefani, Ramponi and Dobson1999).

Food processing conditions can destabilise the native conformation of proteins and thus may promote protein fibrillation (Jansens et al., Reference Jansens, Rombouts, Grootaert, Brijs, Van Camp, Van der Meeren, Rousseau, Schymkowitz and Delcour2019; Lambrecht et al., Reference Lambrecht, Jansens, Rombouts, Brijs, Rousseau, Schymkowitz and Delcour2019; Monge-Morera et al., Reference Monge-Morera, Lambrecht, Deleu, Gallardo, Louros, De Vleeschouwer, Rousseau, Schymkowitz and Delcour2020). So far, the presence of amyloids in common foodstuffs has been confirmed for only a few products. Probably, the most widely cited work in this matter is by Solomon et al. (Reference Solomon, Richey, Murphy, Weiss, Wall, Westermark and Westermark2007). It provides the proof that foie gras contains amyloids and has amyloidogenic potential. Recently, it has been shown that amyloids can be formed during the boiling of egg white (Monge-Morera et al., Reference Monge-Morera, Lambrecht, Deleu, Gallardo, Louros, De Vleeschouwer, Rousseau, Schymkowitz and Delcour2020). According to a study by Yoshida et al. (Reference Yoshida, Zhang, Fu, Higuchi and Ikeda2009), renal and muscular tissues of aged cattle may also contain amyloids. The reports on detection of amyloids in food products are limited and thus more research are needed.

Although studies on the presence of amyloid in foods are scarce, efforts to obtain and test these aggregates from food proteins for potential use in the food industry are extensive (Mohammadian and Madadlou, Reference Mohammadian and Madadlou2018). Research such as this aims to improve the properties of the product or to give them new features (Cao and Mezzenga, Reference Cao and Mezzenga2019). Exceptionally large number of studies were performed for milk proteins. The comprehensive description of these works can be found in the review of Lambrecht et al. (Reference Lambrecht, Jansens, Rombouts, Brijs, Rousseau, Schymkowitz and Delcour2019). On the basis of experimental evidence, it is apparent that milk proteins readily form amyloids in-vitro (Al-Shabib et al., Reference Al-Shabib, Khan, Malik, Sen, Alsenaidy, Husain, Alsenaid, Khan, Choudhry, Zamzami, Khan and Shahzad2019).

Taking all this into consideration, it would be interesting to address the hypothesis that amyloids are present in highly processed dairy products. In this work, we conducted tests to detect amyloids in powdered milks. For this purpose, we performed thioflavin T fluorescence assay, X-ray powder diffraction, atomic force microscopy and fluorescence microscopy imaging. The obtained results suggest that reconstituted powdered milk may contain amyloid-like fibrillar objects.

Materials and methods

Preparation of solutions

Three brands of powdered milk were selected for the research. The composition of these products is presented in Table S1 in the online Supplementary File. The products were purchased from a local supermarket. Two brands of milk were intended for feeding infants after birth (milk 1 and 2) and one for feeding older babies over 12 months of age (milk 3). These products are legally classified as ‘foodstuffs for particular nutritional uses’. Milks 1 and 2 were, therefore, infant formulae, originally labelled by the producer as ‘infant milk’. Milk 3 was follow-on formula, originally labelled by the producer as ‘modified milk’. We chose these particular products for several reasons. This type of milk must be of the highest quality. Its composition must be well-balanced to meet the nutritional needs of young babies, and above all, the product must be safe to consume. It is obvious that infants are a very special and fragile group of individuals, and our work can help identify potential hazards, should they exist.

All powdered milks were produced by Europe-wide known manufacturers. The milks were reconstituted in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions and further diluted for analysis. The deionised water used for the solutions preparation was filtered using 0.1 μm syringe filters (Minisart Cat. No. 16553).

Thioflavin T fluorescence assay (ThT assay)

The solution of the milk was diluted in the filtered phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH = 6.7) to a final concentration of 0.8 mg of protein per ml. The 2.5 mM Thioflavin T solution (Sigma-Aldrich Cat. No. T3516) was introduced to milk solution to obtain 25 μM ThT solution. The samples were analysed in a Jasco FP 8300 spectrofluorometer. The excitation wavelength was 440 nm and the emission spectra were collected from 460 to 550 nm. The excitation bandwidth was equal to 5 nm and the emission bandwidth was set to 10 nm. The scan speed was 200 nm/min, the data interval was equal 0.5 nm and the response time was set to 50 ms. The voltage of the photomultiplier was set to 370 V. Three spectra were averaged for each sample.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

The sample of milk was diluted with filtered water to a concentration of 0.05 mg of protein per ml. Fifty microlitres of this solution was placed on the freshly cleaved surface of the mica plate. After 5 min of incubation the plate was washed twice with 50 ul of filtered water and then dried and stored in desiccator. The AFM scans were collected using Nanosurf Easyscan 2 microscope (contact mode). The speed of scan was equal 1.5 s per line, and the images with resolution 512 × 512 px were recorded. The applied force was equal 20 nN. The data were analysed using Gwyddion 2.50 software.

Fluorescence microscopy (FM)

Fluorescence was recorded with the Olympus IX73 inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with the UCPlanFL N 20x/0.70 or LUCPlanFL N 40x/0.60 objectives, a Olympus U-HGLGPS fluorescence light source and a Hamamatsu Orcaflesh 2.8 CMOS digital camera. Blue fluorescence of milk protein aggregates was generated using exciter-emitter filter set dedicated to DAPI (Semrock, IDEX Corporation). Images were recorded using the Olympus cellSens Dimension 1.18 software. The milk solutions were prepared as for the Thioflavin T fluorescence assay.

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD)

The structure of the samples and phase composition were investigated by X-ray powder diffraction (Cu K-α radiation, Rigaku MiniFlex 600 X-Ray diffractometer). The sample of powdered milk was deposited in the glass holder at room temperature, and crystal structures were determined from an XRD pattern measured in the range of 2θ = 20–80°. The analysis and Rietveld refinements were performed with the HighScorePlus software package (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern UK) and the ICDD database.

Results and discussion

The measurement of the thioflavin T fluorescence (ThT assay) is considered as a gold standard for the detection of amyloids in the sample (Biancalana and Koide, Reference Biancalana and Koide2010). The recorded emission spectra for the analysed solutions of the powdered milks are presented in Figure 1. The fluorescence intensities for the samples containing ThT and milk were significantly higher than intensities recorded for the milk in the buffer or the solution of ThT in the absence of milk. This increase is typical for the systems containing amyloid fibrils (Frare et al., Reference Frare, Polverino De Laureto, Zurdo, Dobson and Fontana2004). The positive results of the ThT assay have been previously reported for a raw milk (Lencki, Reference Lencki2007). The authors of the work cited above analysed the casein micelles using the transmission electron microscope. However, they did not show that the tested samples contained mature amyloids.

Fig. 1. Plots of the ThT fluorescence intensity against wavelength for samples of (a) milk with buffer and ThT (b) milk in buffer without ThT (c) buffer with ThT without milk. The fluorescence spectra are shown for Milk 1, Milk 2 and Milk 3 (counted from the left side).

In the current work we analysed the structure of aggregates with atomic force microscopy (AFM). The obtained height images are presented in Figure 2. We observed fibrillar objects in all samples. The morphology of the fibrils was similar to amyloids formed from β-lactoglobulin (Bolisetty et al., Reference Bolisetty, Adamcik and Mezzenga2011) and α-lactalbumin (Antosova et al., Reference Antosova, Bednarikova, Koneracka, Antal, Zavisova, Kubovcikova, Wu, Wang and Gazova2019) but different than for κ-casein amyloids (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee, Paik, Yeom and Char2019). The objects found in samples of milk 1 and 2 were 0.5–2.5 μm long and 5–7 nm high. There were fewer fibrils in the sample of milk 3 and their morphology was different. These fibrils were longer (1.2–2.8 μm) and somewhat thicker (5–13 nm). Moreover, they did not form clusters and were rather straight. In all samples, small spherical objects were adsorbed to the fibrils. The aggregates reported by us have different morphology than objects presented in earlier research (Lencki, Reference Lencki2007; Qi, Reference Qi2007) in which authors analysed the structure of the casein micelles.

Fig. 2. Atomic force microscopy height images of the analysed samples (a) milk 1 (b) milk 2 (c) milk 3. Scale bar 1 μm.

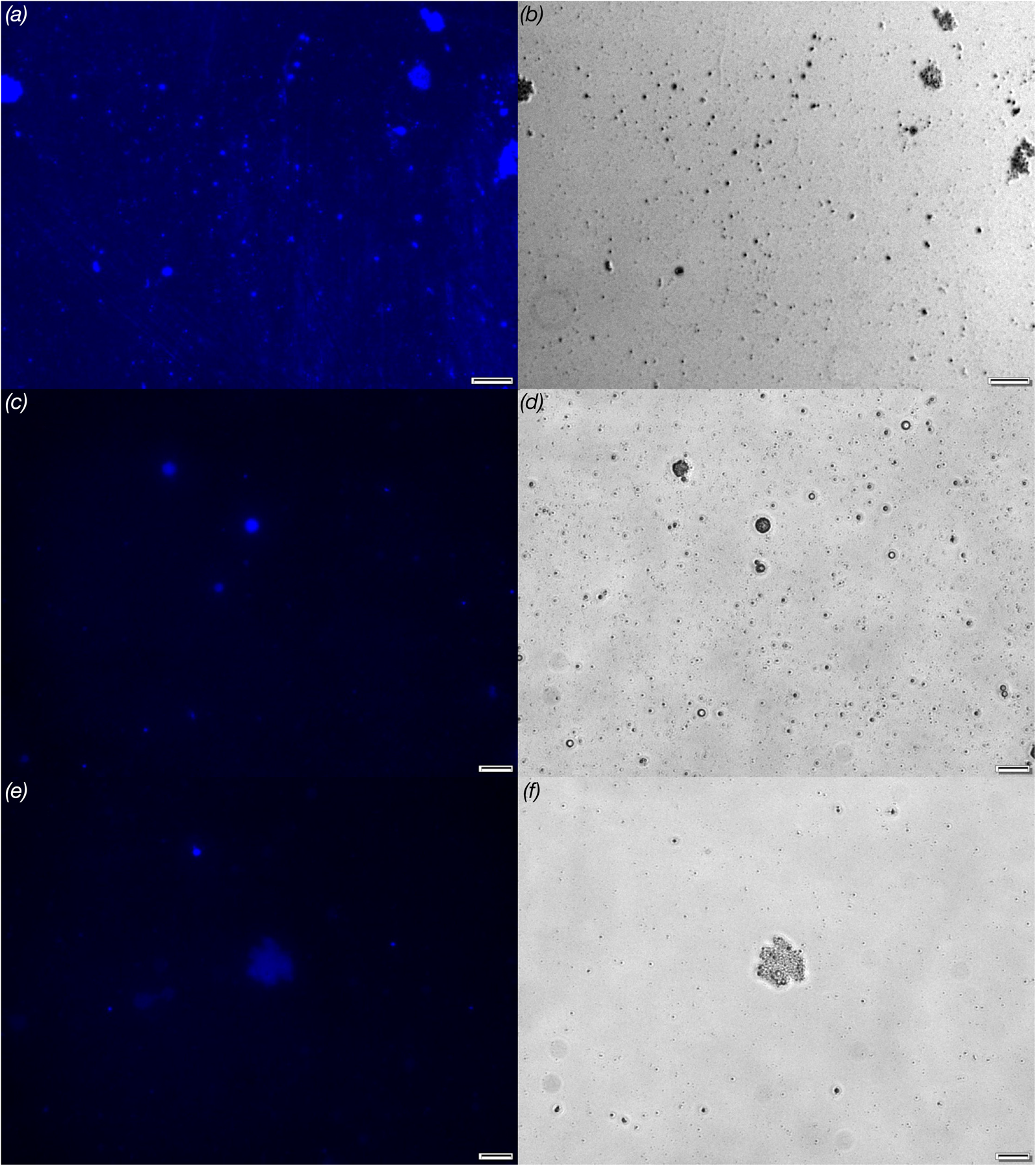

The aggregates in samples of milks were visualised by fluorescence microscopy. We performed the analysis using Thioflavin T as a molecular probe and the samples were prepared as for the fluorescence spectroscopy. The obtained results are shown in Figure 3. In all samples small spherical objects were observed with size around 1–2 μm. Larger clusters with the diameter ranging from 10 μm to more than 20 μm were also present. These aggregates had a similar granular morphology and substructure composed of smaller objects. Unfortunately, the fluorescence microscopy does not have sufficient resolution to show the amyloids directly. However, the fact that the detected aggregates were fluorescent indicates that they may contain amyloid fibrils.

Fig. 3. Fluorescence microscopy visualisation of free floating milk protein aggregates labelled by Thioflavin T: (a) milk 1, (c) milk 2 and (e) milk 3. The panels (b, d, f) represent phase-contrast images of corresponding fluorescence images. Scale bars correspond to 20 μm.

Additionally, the powdered milks were analysed using X-ray powder diffraction (see online Supplementary File materials and methods). The sharp diffraction peaks indicate that the samples contained well-ordered crystalline compounds. The recorded pattern can be interpreted as evidence of the presence of amyloids or may result from the presence of crystalline forms of low molecular weight compounds.

As mentioned in the introduction, the hypothesis that food products may contain amyloids has been presented before (Jansens et al., Reference Jansens, Rombouts, Grootaert, Brijs, Van Camp, Van der Meeren, Rousseau, Schymkowitz and Delcour2019; Lambrecht et al., Reference Lambrecht, Jansens, Rombouts, Brijs, Rousseau, Schymkowitz and Delcour2019; Monge-Morera et al., Reference Monge-Morera, Lambrecht, Deleu, Gallardo, Louros, De Vleeschouwer, Rousseau, Schymkowitz and Delcour2020). Our study confirms these predictions. It is possible that the fibrillar nano-structures discovered in the powdered milks were generated during food processing (Broersen, Reference Broersen2020) or were intentionally added by manufacturers. It also cannot be ruled out that the amyloids were introduced through the starting material. Therefore, it would be advisable to conduct additional research, preferably in the form of comparative studies. The raw milk and the powdered milk synthesised from it could be analysed to search for amyloid fibrils and verify this hypothesis.

The use of amyloids in the food industry raises concerns about their impact on consumers' health (Chaudhry et al., Reference Chaudhry, Scotter, Blackburn, Ross, Boxall, Castle, Aitken and Watkins2008). Risk may result from several reasons:

• The amyloids of food proteins may be cytotoxic (Mocanu et al., Reference Mocanu, Ganea, Siposova, Filippi, Demjen, Marek, Bednarikova, Antosova, Baran and Gazova2014)

• Amyloid seeds introduced to solution of protein monomers eliminate induction time of amyloidogenesis and thus the fibrillation may be significantly faster (Dubey et al., Reference Dubey, Anand, Temgire and Kar2014).

• Cross-seeding experiments showed that the introduction of preformed fibrils to various systems increased the risk of transformation of unlike proteins into amyloids (Dubey et al., Reference Dubey, Anand, Temgire and Kar2014).

• Amyloids from food proteins may have amyloidogenic potential. This risk was highlighted in in-vivo experiments (in mouse models) using amyloids isolated from tissues of aged cattle (Yoshida et al., Reference Yoshida, Zhang, Fu, Higuchi and Ikeda2009) and foie gras (Solomon et al., Reference Solomon, Richey, Murphy, Weiss, Wall, Westermark and Westermark2007). The other examples of the oral transmission of amyloid related diseases in animals can be found in published research by Murakami et al. (Reference Murakami, Ishiguro and Higuchi2014).

• Ingestion of products contaminated with amyloids may induce neurodegenerative diseases in humans.

The transmissible spongiform encephalopathies are the most widely known amyloid-related diseases that might potentially be caused by consumption of contaminated food products. The family of these fatal disorders includes Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and Kuru disease, the latter transmitted during cannibalistic rituals (Sikorska and Liberski, Reference Sikorska and Liberski2012). Worryingly, both these diseases have a long incubation period, years or even decades (Ghani et al., Reference Ghani, Ferguson, Donnelly, Hagenaars and Anderson1998; Collinge et al., Reference Collinge, Whitfield, McKintosh, Frosh, Mead, Hill, Brandner, Thomas and Alpers2008). This fact potentially makes it more difficult to take preventive action and limit damage to the population caused by infectious agents. The suggestion that diet may play an important role in development of protein misfolding diseases was formulated over 20 years ago (Cathcart and Elliott-Bryant, Reference Cathcart and Elliott-Bryant1999) but currently remains a hypothesis. Our research can lead to the identification of additional dietary guidelines for people from at-risk groups.

The results obtained by us can be interpreted in two opposite ways. The presence of amyloids could be considered as a hazard due to the fact that food products may induce amyloid related diseases. On the other hand, prevalence of amyloids in traditionally consumed foodstuffs could serve as a non-direct proof that fibrils of food proteins are safe and do not pose a threat for consumers. To resolve this dilemma more studies are needed (Cao and Mezzenga, Reference Cao and Mezzenga2019; Jansens et al., Reference Jansens, Rombouts, Grootaert, Brijs, Van Camp, Van der Meeren, Rousseau, Schymkowitz and Delcour2019).

Another challenge is to determine how contaminants and legally added substances influence the amyloidogenesis of food proteins. For instance, milk and milk-based products may contain various additives (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Min, Duan, Wu and Li2014), each of which may alter the course of amyloid generation. Our previous works (Wawer et al., Reference Wawer, Szociński, Olszewski, Piątek, Naczk and Krakowiak2019, Reference Wawer, Kaczkowska, Karczewski, Augustin-Nowacka and Krakowiak2021) show that fibrillation can be strongly affected by these types of compounds.

In conclusion, our data point to the presence of amyloid structures in powdered milks. The origin of these amyloids and the significance (if any) of their presence to consumers is still to be elucidated.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S002202992300002X

Acknowledgement

Support from the Faculty of Chemistry of the Gdańsk University of Technology is acknowledged.