The early social history of handaxes

Acheulean handaxes are one of the most heavily investigated Palaeolithic artefacts. They also represent one of the few stone artefact types to have made their way into popular culture. In part, this is due to their substantial temporal and geographical archaeological presence (de la Torre Reference de la Torre2016; Gowlett Reference Gowlett2015; Key et al. Reference Key, Jarić and Roberts2021; Moncel et al. Reference Moncel, Vialet and Arzarello2018), which is only exceeded by expedient stone flake technologies. Their scientific and cultural dominance can also be linked to the formation of prehistoric archaeology as a discipline and the public's subsequent fascination with human origins research (Sackett Reference Sackett2000; Schlanger Reference Schlanger2002). Indeed, as White (Reference White2022, 1) recently stated, the handaxe ‘is a most iconic and emotive object, one that sometimes fills the modern beholder with a vivid sense of their ancestors’ feelings by drawing on the same basic emotional and reward systems’.

The history—as opposed to prehistory—of handaxes being used within human social systems is not widely researched, but it can be traced in the English written record to the mid 1600s. At this time, widespread gravel aggregate extraction, the rise of antiquarianism and the European Enlightenment resulted in increased discovery rates of, and subsequent interest in, these unusually flaked stone objects (Goodrum Reference Goodrum2008; Johanson Reference Johanson2009). With this increased interest came increased scrutiny and, in turn, the first published accounts of handaxes as human-made objects (Dugdale Reference Dugdale1656; Bagford Reference Bagford and Hearne1715). The depth of their antiquity was not accepted until the nineteenth century (Frere Reference Frere1797; Boucher de Perthes Reference Boucher de Perthes1847; Rigollot Reference Rigollot1854; Prestwich Reference Prestwich1860; Evans Reference Evans1872), and their pre-Homo sapiens origin was not revealed until much later (Sackett Reference Sackett2000). It is, nonetheless, known that from 1656 onwards handaxes started to be formally investigated and went on to become a major focus in the emerging field of archaeology (Schlanger Reference Schlanger2002), and later, prehistoric archaeology. Sackett (Reference Sackett2000), Key and Lycett (Reference Key and Lycett2017) and White (Reference White2022) provide detailed reviews of seventeenth- to nineteenth-century developments concerning the handaxe, while Gowlett (Reference Gowlett, Hosfield, Wenban-Smith and Pope2009), McNabb (Reference McNabb, Hosfield, Wenban-Smith and Pope2009), Pope and Roberts (Reference Pope, Roberts, Hosfield, Wenban-Smith and Pope2009), Pettitt and White (Reference Pettitt and White2011), and others (see Hosfield et al. Reference Hosfield, Wenban-Smith and Pope2009) provide reviews of the key individuals involved in these debates. We refer the reader to these texts for further information.

Here, we are concerned with the pre-seventeenth-century social history of handaxes. For such information we often rely on the early oral histories of European populations, as recorded in the above-stated seventeenth- to nineteenth-century works (e.g. King Reference King1867; Evans Reference Evans1872; Van Andel Reference Van Andel1924). From these texts, it is widely stated that prior to the Enlightenment handaxes were often considered to be of natural origin and were thought to have been ‘shot from the clouds’ when lightning struck the ground (King Reference King1867, 77). Sixteenth-century natural historians across Europe noted the presence of ‘ceraunia’ or ‘thunderstones’, which were ‘curiously shaped stone objects … treated as a naturally occurring geological phenomenon’ formed through lightning strikes (Goodrum Reference Goodrum2002, 257). This explanation for the presence of handaxes has a long history, with Turner and Wymer (Reference Turner and Wymer1987) suggesting 44 Roman-deposited Palaeolithic handaxes from Witham, UK, to have been a possible tribute to Jupiter, a Roman god often depicted wielding thunderbolts. Moreover, Pliny the Elder (Natural History 37.51) describes red ‘elongated’ ceraunia ‘resembling axe-heads’, which were considered by the Magi to be found ‘only in a place that has been struck by a thunderbolt’.

Ceraunia were a broad category of objects that not only included handaxes, but also included other prehistoric implements of both flaked and ground origin, and fossilized sea urchins (Goodrum Reference Goodrum2008; King Reference King1867). Descriptions of some ceraunia are, however, undeniable in their resemblance to handaxes and other later bifacial tools, being ‘a heterogeneous category of stones of varying color that are shaped like pyramids, wedges, hammers, spheres, or are sometimes triangular’ (Goodrum Reference Goodrum2002, 488). It is reported that Mercati (1541–1593) was the first to note similarities in the form of ceraunia and lithic arrowheads being brought back from the Americas (Accordi Reference Accordi1980). The publication of Mercati's ideas did not, however, occur until 1717, more than a century after his death, which means that his original insight was lost until after the Enlightenment.

Prior to 1717, handaxe-like stone ceraunia forms had already been discussed, with pyramidal shapes being described by Camillo Leonardi as early as 1502 (Goodrum Reference Goodrum2008; Leonardi Reference Leonardi1610) and pyramidal to wedge forms being described by Konrad Gesner (Reference Gesner1565). Whether pyramidal ceraunia mean handaxes is hard to say with any certainty, but it is surely the case that Gesner (Reference Gesner1565) was talking about at least one type of bifacially flaked stone implement. For these early accounts, and others (e.g. Tittelmans Reference Tittelmans1545), it was still often the case that ceraunia—handaxes or not—originated in the sky and were deposited where lightning struck (Goodrum Reference Goodrum2008). Gesner (Reference Gesner1565), as described by Goodrum (Reference Goodrum2008), even notes a specific instance of a thunderstone supposedly falling to earth during a storm in 1492. Earlier oral accounts of ‘thunderbolts’ or ‘thunderstones’ can occasionally be traced to the eleventh to thirteenth century in northern Europe (Johanson Reference Johanson2009), but in at least some instances these are in latitudes above the known European Acheulean range, suggesting they refer to later Palaeolithic, Mesolithic or Neolithic technologies. The German scholar Georgius Agricola (Reference Agricola1546) notably and uniquely took exception with a lightning-strike origin, writing that ‘ceraunia received its name in the same manner as the above minerals for the ignorant believe [sic] it falls during flashes of lightening [sic]’ (translation Bandy & Bandy Reference Bandy and Bandy1955).

To our knowledge, the mid 1500s provide the earliest recorded (written or otherwise) instances of ceraunia or ‘thunderstones’ which likely include handaxes. Whether Pliny the Elder (first century ce) and other pre-sixteenth-century accounts (Johanson Reference Johanson2009) were only discussing Neolithic or other axe heads, we do not know. It is possible (even likely) that references to handaxes—in one form or another, potentially even in reference to them being human-made—exist in other early texts and may one day come to interest medieval or classical historians. Regardless, there are strong indications that the social history of handaxes extends beyond their seventeenth-century acceptance as human-made objects. What is currently lacking in the Palaeolithic literature is any conclusive—not just suggestive (e.g. ‘pyramidal’ or ‘triangular’ ceraunia forms)—evidence of handaxes prior to the seventeenth century. Moreover, there is little record of their role within society in these earlier occurrences (although see Johanson Reference Johanson2009; King Reference King1867), or unequivocal evidence of their acceptance as objects with societal value prior to the seventeenth century. Indeed, despite the widely repeated interpretation of Turner and Wymer (Reference Turner and Wymer1987), we can only securely state that a collection of prehistoric handaxes was intentionally deposited by Romans beneath a structure. This does not go much further than Frere's (Reference Frere1797) reporting of workmen depositing baskets full of handaxes to fix ruts in roads. Here, we provide a brief report on the fifteenth-century depiction of a stone object with a striking resemblance to an Acheulean handaxe. Importantly, the image in question securely places the object within an important social context.

Jean Fouquet's Étienne Chevalier with Saint Stephen

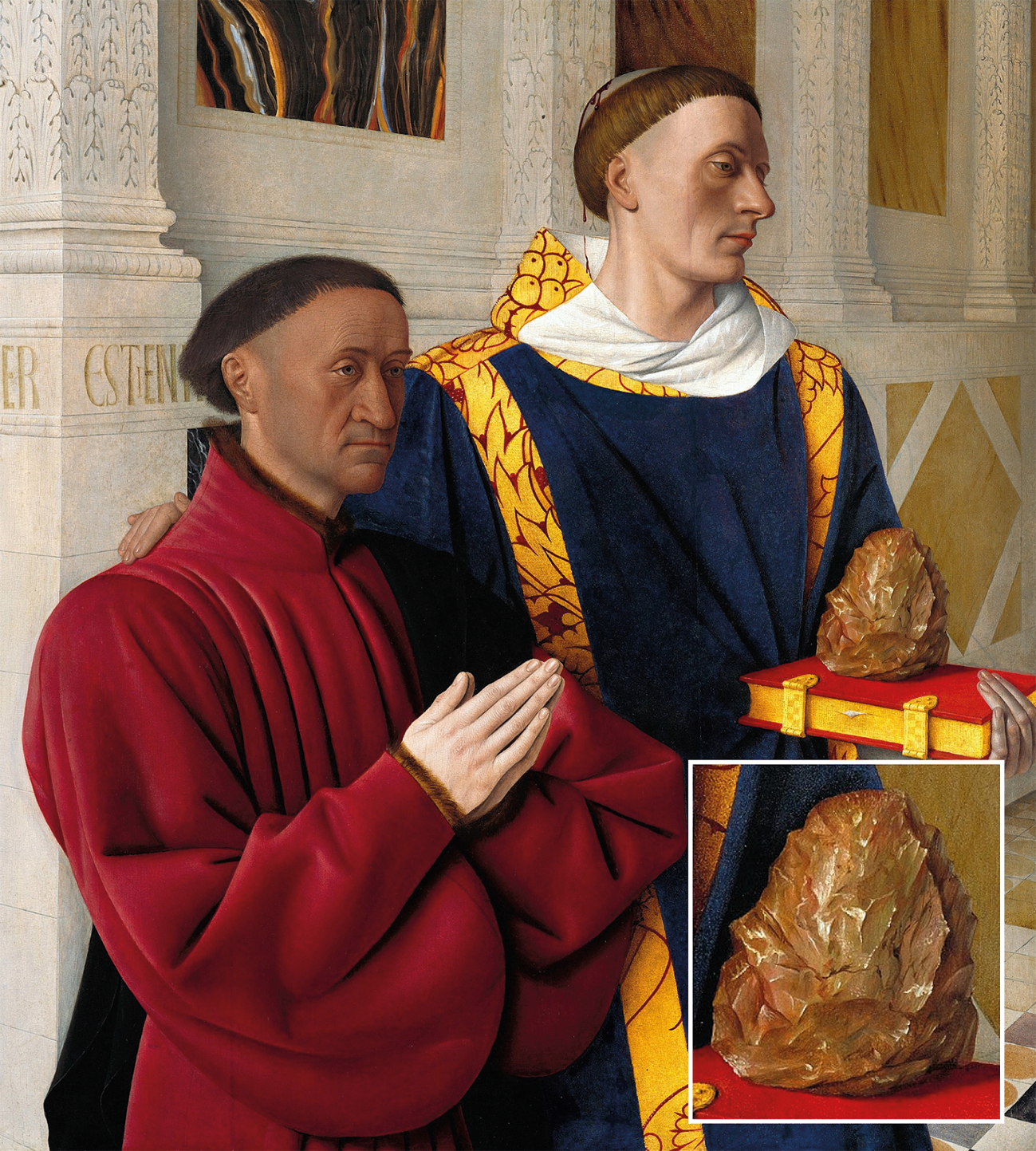

The object under discussion appears in Étienne Chevalier with Saint Stephen, an oil-painting on wood that is currently housed in the Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Germany) (Fig. 1). Painted c. 1455, it is one of the two panels of the so-called Melun Diptych (Supplementary Material 1). Although unsigned, the Melun Diptych is ascribed to the French artist Jean Fouquet, who was later to become the court painter to King Louis XI of France (Seidel & Kemperdick Reference Seidel and Kemperdick2018). The diptych's inclusion among many introductory art history textbooks underlines its significance within the corpus of fifteenth-century northern European art (Inglis Reference Inglis2011; Stokstad Reference Stokstad2009). We suggest that this work's significance extends in previously unrecognized ways to include a singular contribution to the history of science, in particular the social history of Acheulean handaxes.

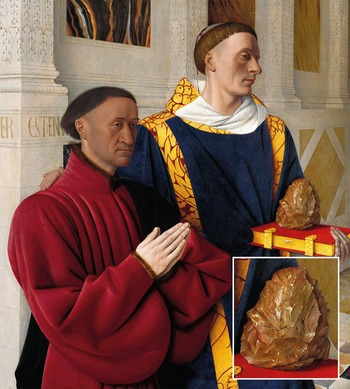

Figure 1. Jean Fouquet's Étienne Chevalier with Saint Stephen, left panel of the Melun Diptych, painted c. 1455. Étienne Chevalier is in red, while Saint Stephen, in blue, accompanies him. The handaxe-like object (inset) rests upon a book and serves to identify Saint Stephen, who was stoned to death. (Reproduced and modified here under a creative commons licence after a provision by the Yorck Project (Directmedia) to Wikimedia Commons.)

Fouquet is considered one of the most important French artists immediately prior to and during the birth of the early Renaissance. He worked in a variety of mediums but is especially known as a painter of illuminated manuscripts, as well as wooden panels executed in the then new medium of oil paint. Oil permitted unparalleled accuracy and detail in rendering objects through the layering of colours. In addition, oil has the extraordinary capacity to reflect light, resulting in rich, luminous images, and thus became a medium of great distinction (Inglis Reference Inglis2011; Kemperdick Reference Kemperdick2018). The Melun Diptych and the Hours of Étienne Chevalier are considered among Fouquet's most famous and important works.

The Melun Diptych was commissioned by Étienne Chevalier, a native of Melun, France, who was Treasurer for Louis XI's predecessor King Charles VII. It was composed of two wooden panels hinged together and was originally displayed in the collegiate church of Notre-Dame in Melun, in the private chapel and above the tomb of the donor, Chevalier (Inglis Reference Inglis2011). The left panel (Fig. 1) features the donor himself, who appears in a prayerful pose, wearing a fur-lined, crimson robe, as often worn by royal officials (Fircks Reference Fircks and Kemperdick2018). He is rendered in a realistic, portrait-like style. His presence in a sacred context signifies the private devotional function of the work. Indeed, in northern Europe the fifteenth century witnessed the emergence of a class of private art patrons who wished to be immortalized in public frameworks such as a church altarpiece, showcasing their piety, status and wealth (Gelfand Reference Gelfand1994). In the diptych, Chevalier is shown alongside St Stephen, his patron saint, whom the New Testament presented as the first Christian martyr and whose martyrdom entailed death by stoning. The donor and St Stephen are rendered as life-like, three-dimensional figures in a clearly defined realistic architectural setting of ornate pilasters and marble panels.

Around 1773 the left panel was separated from its companion, which shows the enthroned Virgin Mary and the Christ Child (Kemperdick Reference Kemperdick2018; Kren Reference Kren and Kemperdick2018), toward whom both male figures directed their attention (Supplementary Material 1). The right panel is now in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp. Both panels underscore the artist's painstaking observation, especially notable, for example, in the rendering of the Virgin's gold and veined-marble throne, which is embellished with sparkling jewels and golden tassels, or in St Stephen's costume. As the queen of heaven, the Virgin wears a magnificent crown adorned with strikingly naturalistic pearls and precious stones. The employment of naturalism is, however, selective. The rendering of the two male figures of the left panel is marked by stylization, idealization and geometry, while the Virgin is even more highly idealized. Despite the idealization of the human figures, both panels display the same precise rendering of inanimate features, ‘realia’ such as cloth, jewels, architectural details, as well as the stone object held by St Stephen, which is our focus in this article. This large, ‘sharp-edged stone’ is the instrument of the standing saint's martyrdom (Kemperdick Reference Kemperdick2018). It rests on a closed, vermilion book with gold-tipped pages and gold hinges held by the saint's left hand. Stephen rests his right hand on Chevalier's shoulder. He is further characterized by his tonsure, which bears another sign of his martyrdom, a trace of blood visible at the top of his scalp. Although the Virgin's gaze is downturned, the child's gaze engages with St Stephen's attributes of book and stone object, as does his pointing finger, which also directs the viewer.

Scholarly interest in this work has focused exclusively on the figures and the painting's context, while little attention has been paid to the stone object the martyr holds, which is typically referred to simply as a ‘stone’ (Davies et al. Reference Davies2012, 494; Kleiner Reference Kleiner2010, 412; Stokstad Reference Stokstad2009, 610), a ‘jagged stone’, or a ‘large sharp stone’ (Gombrich Reference Gombrich1966, 199). Fouquet emphasizes the stone's luminous surface and texture, which matches the style of other contemporaneous Flemish artists who were accomplished at creating the illusion of the here-and-now. The stone object is evidently sharp-edged with a tapering tip and globular ‘butt’—typical features for Acheulean handaxes (Gowlett Reference Gowlett, Goren-Inbar and Sharon2006). In the knowledge that works of art are not exact transcripts of reality, it would be difficult, if not impossible, conclusively to identify whether a handaxe is represented in this fifteenth-century painting. We can, however, potentially strengthen the inference that a handaxe is depicted through three artefact-based routes of inquiry.

Is a handaxe depicted?

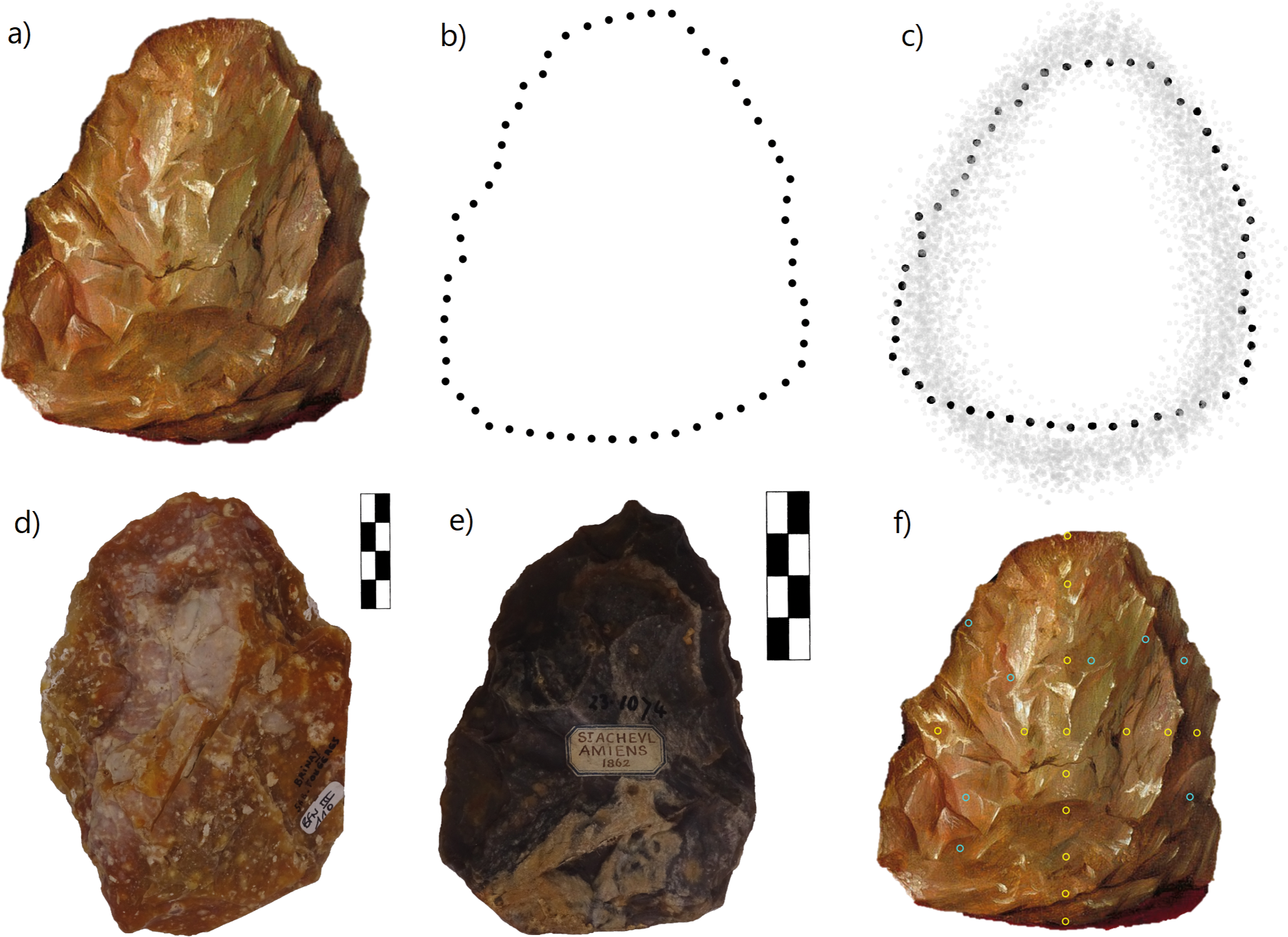

First, the stone object appears to have been painted square-on to the observer, so that if it was a handaxe then the 2D outline of the tool is visible within the painting. That is, the shape profile of the potential handaxe, and therefore the shape information potentially imposed by an Acheulean hominin, has been retained. In turn, it is possible to compare the shape of this stone object to handaxe artefacts from known Acheulean assemblages. If the object is found to be within the shape space of confirmed Acheulean assemblages, particularly those from northern France, then it strengthens the inference that an Acheulean handaxe is depicted in the painting, and the social history of these artefacts can be pushed back to the fifteenth century.

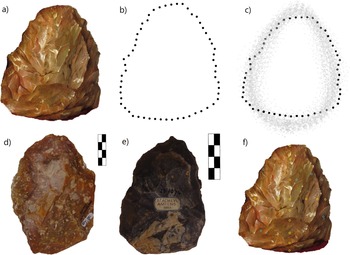

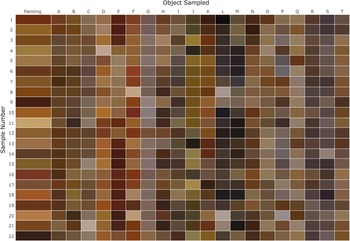

Second, the stone object's colouration is notable for its similarity to numerous flint handaxes recovered from Quaternary gravel and sand deposits in northwest France and eastern Britain (Fig. 2) (e.g. Antoine et al. Reference Antoine, Moncel and Limondin-Lozouet2016; Dale Reference Dale2022; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Ashton, Hatch, Hoare and Lewis2021; Hosfield Reference Hosfield2011; Moncel et al. Reference Moncel, Despriée and Voinchet2013; Reference Moncel, Despriée and Voinchet2016). If the colours in the painting match those on artefacts from deposits found in northern France, where Fouquet lived and worked, then the inference that a handaxe is depicted will again be strengthened.

Figure 2. (a) A close-up of the stone object depicted in Étienne Chevalier with Saint Stephen alongside (b) the raw outline coordinates used for the EFA analysis and (c) the Procrustes-transformed coordinates for the painted stone object are shown alongside all other artefacts used in the EFA. Acheulean handaxes from La Noira (d) and Saint Acheul (e) are also shown. Note their similar colours and shape to the object painted by Fouquet. A representation of the colour-sampling method is also shown (f), with the vertical and horizontal axis sampling location in yellow, and the eight locations of maximum colour diversity in teal.

Third, while the object is not depicted using the black-ink line illustrations traditionally used in Palaeolithic studies, it nonetheless appears that flake scars have been depicted. Some appear unusually abrupt and irregular—and somewhat akin to frost-fractures found in some flint nodules or flaked flint cores—but others, particularly on the right edge, have the characteristic shallow concavity left behind by flake platforms, and the majority of ridges lead invasively toward the centre of the object. If the number of ‘flake scars’ visible on the painting is similar to those from northern European Acheulean exemplars, then again the inference that a handaxe artefact is depicted will be strengthened.

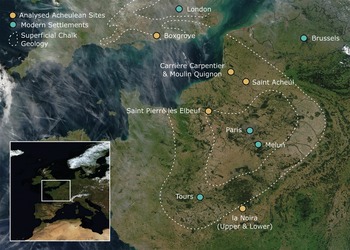

Further, it is important to highlight circumstantial factors that suggest Fouquet, and the wider medieval population of northern France, may have been exposed to Acheulean handaxes c. 1455. To start, evidence indicates ancient handaxes to have been rediscovered after millennia and repurposed in prehistory (Brumm et al. Reference Brumm, Pope, Leroyer, Emery, Overmann and Coolidge2019), or to naturally appear on the surface of landscapes as a result of geological processes (Blundell Reference Blundell2016; Pope et al. Reference Pope, Blundell, Scott and Cutler2016), suggesting their presence in natural landscapes absent of the industrial quarrying processes often linked to their discovery in northwestern Europe (e.g. Bridgland et al. Reference Bridgland, Antoine, Limondin-Lozouet, Santisteban, Westaway and White2006; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Ashton, Hatch, Hoare and Lewis2021; Moncel et al. Reference Moncel, Antoine, Hurel and Bahain2021a). Beyond this, however, medieval populations did quarry gravels and stone from Quaternary deposits, with some of these medieval quarries having since been demonstrated to retain prehistoric artefacts, while other Palaeolithic deposits are located very close to medieval abbeys, settlements and fortifications (e.g. Bradley & Gaimster Reference Bradley and Gaimster2002; Clarke Reference Clarke2006; Fletcher Reference Fletcher2010; Key et al. Reference Key, Lauer, Skinner, Pope, Bridgland, Nobel and Proffitt2022; Leroyer & Cliquet Reference Leroyer and Cliquet2010; Moncel et al. Reference Moncel, Antoine, Herisson, Locht, Voinchet and Bahain2021b). Moreover, and as noted earlier, flaked stone artefacts—irrespective of whether they are handaxes or not—were known to populations at this time under the guise of being ceraunia or ‘thunderstones’ (see above).

Tours (France), where Fouquet was born and undertook much of his work, is also close to chalk bedrock, meaning that if Acheulean hominins had made handaxes in this region, then flint would have been available (Fig. 3). Indeed, northern Europe's earliest handaxe artefacts, found at the site of la Noira ~100 km to the southeast of Tours (Moncel et al. Reference Moncel, Despriée and Voinchet2013; Reference Moncel, Despriée and Voinchet2016; Reference Moncel, Despriée, Courcimaut, Voinchet and Bahain2020), are made from millstone (lower level) or flint and millstone (upper level). Further, la Noira is located on the river Cher, a tributary of the Loire, on which the more westerly Tours is located. Both the Cher and Loire valleys are known for their Quaternary terraces, with other flint Acheulean sites having been reported in addition to la Noira (Despriée et al. Reference Despriée, Voinchet, Tissoux and Moncel2010; Reference Despriée, Voinchet, Tissoux and Bahain2011; Hérisson et al. Reference Hérisson, Airvaux, Lenoble, Richter, Claud and Primault2016). The same can be said about the town of Melun, where the panel was located. Furthermore, assuming that the panel had been painted locally to Notre Dame de Melun, it is significant that flint handaxe artefacts and Quaternary gravels are known to be present in this area of the Paris Basin (Blaser & Chaussé Reference Blaser and Chaussé2016; Cliquet et al. Reference Cliquet, Lautridou, Antoine, Lamothe, Leroyer, Limondin Lozouet and Mercier2009; Leroyer & Cliquet Reference Leroyer and Cliquet2010; Lhomme Reference Lhomme2007; Limondin-Lozouet et al. Reference Limondin-Lozouet, Nicoud and Antoine2010). Indeed, the idea that at least some flint Acheulean handaxes were found during the medieval period of northern and central France and made their way into the cultural sphere of Fouquet appears likely.

Figure 3. A map of northern Europe detailing the regional Acheulean sites used as part of the investigation (yellow), an outline of the superficial chalk geology of the region (white dotted line), and several modern settlements discussed in the article (teal). (Original satellite image: NASA Visible Earth Project.)

Shape analysis

It is only possible to undertake 2D analyses of the painted stone object's shape, meaning that the Acheulean assemblages it is compared to must be treated similarly. While some of the most characteristic shape attributes of handaxes are visible through 2D analyses (e.g. Costa Reference Costa, Lycett and Chauhan2010; Herzlinger et al. Reference Herzlinger, Goren-Inbar and Grosman2017; Iovita Reference Iovita, Lycett and Chauhan2010; Lycett & von Cramon-Taubadel Reference Lycett and von Cramon-Taubadel2008; McPherron Reference McPherron2000; Saragusti et al. Reference Saragusti, Sharon, Katzenelson and Avnir1998; Vaughan Reference Vaughan2001), this is nonetheless an important limitation of the present analyses (Lycett et al. Reference Lycett, von Cramon-Taubadel and Foley2006). We employed two widely used 2D shape analysis methods to investigate how the stone object's outline shape compares to Acheulean handaxe assemblages. The artefact samples for each method vary as they are drawn from previous studies independently undertaken by AK and JC (Clark Reference Clark2023, preprint; Key Reference Key2019).

The first method uses a Cartesian coordinate grid system widely applied to record the outline shape of the superior or inferior surfaces of Acheulean handaxes (Costa Reference Costa, Lycett and Chauhan2010; Lycett et al. Reference Lycett, von Cramon-Taubadel and Foley2006). The method is known to reliably describe the outline shape of lithic artefacts, facilitating comparisons between different handaxe assemblages and the placement of individual handaxes within the wider assemblage-level contexts (Arroyo et al. Reference Arroyo, Proffitt and Key2019; Eren et al. Reference Eren, Roos, Story, von Cramon-Taubadel and Lycett2014; Lycett & von Cramon-Taubadel Reference Lycett and von Cramon-Taubadel2008; Pargeter et al. Reference Pargeter, Khreisheh and Stout2019; Schillinger et al. Reference Schillinger, Mesoudi and Lycett2014). A detailed description of the Cartesian coordinate analyses can be found in Supplementary material (online). Shape data were recorded from the painted stone object at an arbitrary scale where its maximum length equalled 100 mm. The same data were collected from five Middle Pleistocene Acheulean sites using accurately scaled digital photos of individual artefacts. These sites included Boxgrove (UK, n = 214), Saint-Acheul (France, n = 38), Porzuna (Spain, n = 133), Cunette (Morocco, n = 40) and Tabun (Israel, n = 75), providing a comparative sample from across Europe and its immediate geographic neighbours.

The second technique uses Elliptical Fourier Analysis (EFA), which has again previously been used to study the 2D outline shape of handaxes (Hoggard et al. Reference Hoggard, McNabb and Cole2019; Iovita Reference Iovita, Lycett and Chauhan2010; Iovita & McPherron Reference Iovita and McPherron2011), through the reduction of a handaxe's outline shape into a series of harmonics, each comprising four trigonometric Fourier coefficients. The EFA methods applied here can also be viewed in the Supplementary material. For the EFA analysis, we restricted the artefact sample to five Acheulean sites from northern and central France, comprising six assemblages. This included Moulin Quignon (n = 5) (Antoine et al. Reference Antoine, Moncel and Voinchet2019; Moncel et al. Reference Moncel, Antoine, Herisson, Locht, Hurel and Bahain2022), Carrière Carpentier (n = 5) (Antoine et al. Reference Antoine, Moncel and Limondin-Lozouet2016), Saint-Pierre-Lès-Elbeuf (n = 30) (Cliquet et al. Reference Cliquet, Lautridou, Antoine, Lamothe, Leroyer, Limondin Lozouet and Mercier2009; Leroyer & Cliquet Reference Leroyer and Cliquet2010), Saint-Acheul (n = 30) (Antoine & Limondin-Lozouet Reference Antoine and Limondin-Lozouet2004) and both the upper and lower levels from la Noira (n = 30 for both) (Moncel et al. Reference Moncel, Despriée and Voinchet2013; Reference Moncel, Despriée and Voinchet2016; Reference Moncel, Despriée, Courcimaut, Voinchet and Bahain2020). Note that the Saint-Acheul assemblage is the same one used in the Cartesian coordinate analyses, but the sample of individual handaxes varies. The majority of artefact data were derived from digital photos, with the exception of four of the five handaxes from Moulin Quignon, which were analysed from 2D images presented in Antoine et al. (Reference Antoine, Moncel and Voinchet2019).

Prior to applying both techniques, the outline shape of the stone object was isolated from the background of the painting. PCA analyses were used to reduce the 20 Cartesian coordinate measurements and first 30 EFA harmonics, for all tools in the two sets of analyses respectively, into individual data points (principal components) that describe each tool's shape. Principal component plots were then used to display the shape space of handaxes in each of the analysed handaxe assemblages. The shape of the Fouquet object was then plotted against these assemblages. As noted already, artworks are not necessarily accurate depictions of reality, but Fouquet appears to have rendered the stone object with care and detail. Thus, while some distortion to the original object—whether recreated from memory or from direct observation of a stone that was in front of the artist—could be considered inevitable, we believe its form to be intentional and a broadly faithful representation of a known object. As we shall note below, Fouquet's rendering deviates from traditional depictions of the stones that martyred St Stephen.

Colour analysis

The open-source image-editing software Inkscape was used to identify RGBA colours from the surface of the painted object. The painting's colouration was used as depicted in Figure 1. In total, 22 pixels on the object's digital image were sampled; 14 were selected from the vertical and horizontal midlines of the object (i.e. vertical axis midway [50%] along the line of maximum width, and the horizontal axis midway [50%] down the line of maximum symmetry, both after orientation), while a further eight were sampled from any location on the tool (Fig. 2). In all instances, locations were chosen with the intention of maximizing the range of colours sampled from any one tool. The only areas excluded were those painted white (or off-white) to depict the object's shiny surface. This process was repeated for 20 randomly selected handaxes from the French Acheulean site sample outlined above (i.e. Moulin Quignon, Carrière Carpentier, Saint-Pierre-Lès-Elbeuf, Saint-Acheul, la Noira Upper and la Noira Lower). Almost all areas on the superior surface of the handaxe artefacts were sampled, including portions of the cortex. The only exceptions were paper labels or writing used to catalogue the tools. Due to the pigments and varnish applied, and the length of time since their application, we recognize that a degree of colour distortion—but not fundamental alteration—may now be present in the painting relative to when it was originally crafted by Fouquet, and potentially even to when it was restored in the 1980s (Kemperdick Reference Kemperdick2018).

Flake scar count

The number of flake scars present on the surface of the painted stone object were estimated independently by AK, JC and three other experienced lithic specialists. A sample of 30 randomly selected handaxes from the six above-mentioned French handaxe assemblages also had their flake scars counted by AK and JC, allowing us to contextualize the flake scars in the painting alongside known handaxe artefacts. All artefact flake scar counts were from the most convex surface of the tools. Analysts were not aware of any other scar count predictions prior to completing their assessment of the tools. As no accurate scaling information was present for the painted stone object, we did not apply a threshold above which flake scars were only counted if they exceeded this size.

Results

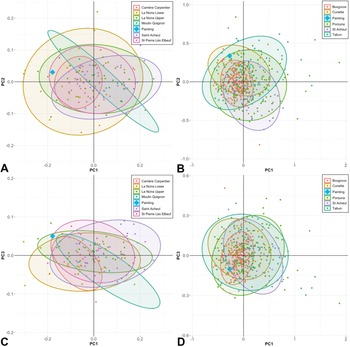

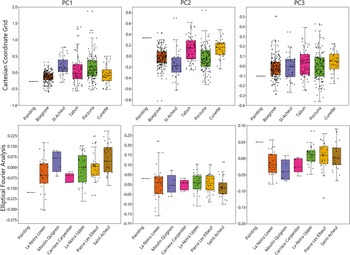

Both shape analysis methods reveal the painted stone object to be within the shape space of diverse Acheulean handaxe assemblages. Using the Cartesian coordinate data, plots of PC1 against PC2, and PC1 against PC3, reveal the shape of the painted object to be within the 95 per cent ellipses of almost all Acheulean assemblages (Fig. 4B) demonstrating that the object sits within expected shape range of diverse Middle Pleistocene Acheulean handaxe assemblages. In this instance, PC1 explained 59 per cent of the shape variation, while PC2 and PC3 explained 25 per cent and 9 per cent, respectively. Using the EFA data, the PC1 versus PC2 plot reveals the painted object to be within the 95 per cent ellipses of three French handaxe assemblages (St-Pierre-Lès-Elbeuf, la Noira Upper and la Noira Lower: Fig. 4A). For the remaining sites, its shape is close to all of their distributions and is clearly within the polled variation, suggesting the object's shape to be consistent with the Acheulean of northern and central France. Here, PC1, PC2 and PC3 explained 62 per cent, 16 per cent and 7 per cent of the shape variation, respectively. The painted object's Cartesian coordinate PC1 and PC3 values, and EFA PC2 values, are on the edges of multiple Acheulean assemblages’ interquartile ranges (Fig. 5). Together, these data suggest the painted object's shape not only to be within the expected shape space for an Acheulean handaxe, but that in some respects its shape is fairly standard for the Acheulean.

Figure 4. Shape space plots of PC1 against PC2 and PC1 against PC3 with 95 per cent ellipses created using the Cartesian and EFA data. (A) and (C) represent the EFA data created using Acheulean samples from northern France, while (B) and (D) represent the Cartesian data created using Acheulean assemblages from France, Spain, Israel, Morocco and the UK. In all instances, the 2D shape of the painted stone object (blue diamond) is within the 95 per cent ellipses of one to four Acheulean handaxe assemblages.

Figure 5. Box-and-whisker plots for PC1, PC2 and PC3 values attributes to each Acheulean handaxe assemblage in both the Cartesian and EFA shape analyses. The painting's principal component value in each instance is presented on the left by a single line/dot. In three instances (Cartesian PC1 and PC3, EFA PC2) the painting is within the 25–75 per cent quartile ranges of multiple handaxe assemblages, while for the others it is more of an outlier but still within the ranges presented by the artefacts. In turn, this supports the inference that the painted stone object represents an Acheulean handaxe artefact.

Figure 6 details the RGBA colours sampled from the surface of the painted object, alongside those collected from 20 French Acheulean handaxes. While there is clearly variation in the colours observed on these artefacts, the yellow-to-brown-to-red hue of the painted object is consistent with many of the artefacts. It is important to note that the lighting used when photographing the handaxes will have made them seem duller relative to the painting, and this explains some of the differences observed. Colour variation within the painted stone could be considered high, but this appears to be replicated in some of the artefacts (for example, objects ‘E’ and ‘K’), and is not unexpected, given the highly variable nature of flint and flint patination.

Figure 6. RGBA colours sampled from the surface of the painted object, alongside those collected from 20 French Acheulean handaxes (A–T). Handaxes A and B are from Carrière Carpentier, C–F are from la Noira Lower, G–I are from la Noira Upper, J was sampled from Moulin Quignon, K–N were selected from Saint-Acheul and O–T were drawn from the Saint-Pierre-Lès-Elbeuf sample.

The estimates returned for the number of flake scars present were 20, 24 (AK), 40, 41 (JC) and 42 flake scars, with an average of 33.4, seemingly indicating two groupings of scar counts, likely dependent on the willingness of each researcher to include small flake scars as intentional removals or not. AK and JC counted flake scars on a further 30 French Acheulean handaxes. The average number of flake scars on these artefacts was identified to be 25.3 (AK) and 41.8 (JC), depending on the analyst, with an average of 33.5. These mean artefact results are, then, near-identical to the painting. These findings indicate that, as far as it is possible to ascertain from the painting, the flake scar count of this object is consistent with those observed on Acheulean handaxes from France.

Discussion and conclusion

We cannot state with absolute certainty that an Acheulean handaxe was painted by Jean Fouquet c. 1455. What we have done is demonstrate, as far as it is possible, that the stone object in the image is likely to be one. This finding pushes the evidenced social history of handaxes back to the mid fifteenth century, a century before probable instances of ‘handaxe-ceraunia’ are described and two centuries before we have secure written and illustrated evidence of handaxes (Frere Reference Frere1797; Boucher de Perthes Reference Boucher de Perthes1847; King Reference King1867; Goodrum Reference Goodrum2002).

While we cannot rule out that a Middle Palaeolithic handaxe could be represented instead, the painted object's colouration—if corresponding to flint—does suggest a heavy patination more often associated with early northern European Acheulean assemblages (Fig. 6). This interpretation is supported by our shape and flake scar analyses, which demonstrate the object to be typical for European Acheulean assemblages. Arguably, the painting's origin in northern France, which is known for its Acheulean assemblages, is another point favouring a mid-Pleistocene age for the depicted object.

Our finding may not be surprising given the substantial number of handaxe artefacts present in Europe, and the ease with which they erode from river terraces or are discovered during farming or building practices. Indeed, in line with previous understanding (Goodrum Reference Goodrum2008; White Reference White2022), the painting is simply confirmation of earlier inferences that handaxes would have been known to pre-seventeenth-century populations (even if not as objects of human creation). While the painting cannot speak to ideas in this period about the creation of handaxes—which may again focus on lightning strikes—the prominent presence of a handaxe within a prestigious and public-facing religious context suggests a symbolic value or social meaning beyond its being an oddly shaped natural rock (see below). Surely, Chevalier must have commissioned the diptych as an expression of his religious piety but also as a signal of his wealth and status.

It is difficult to provide any firm resolution on why a handaxe was used by Fouquet within the painting. It could have been due to this object's ubiquity within society, in which case it would have been depicted due to a shared understanding about such objects. Alternatively, it could have been considered an exceptional object that potentially held an important role within religious, royal and/or ‘learned’ social spheres, and was thus used because it was unfamiliar within wider society. It is equally plausible that Fouquet's depiction of a handaxe is an exceptional one-off that informs us about the artist, without there being a wider medieval context or systematic understanding. If one of the former two options is the case, then there may be further evidence of a social, and potentially religious, role for handaxes within late medieval European contexts.

Certainly, Fouquet's rendering of the object of St Stephen's martyrdom is very unusual. In most depictions of St Stephen, both the narrative ones of his martyrdom and the iconic, the stones that killed him are unremarkably painted, with no great definition or artistic distinction. Rarely do they appear with any detailing. For example, Carlo Crivelli's 1476 depiction of St Stephen in the National Gallery in London showcases three round stones resting, one each, on the head and shoulders of the saint. A notable exception is another work by Jean Fouquet, a miniature included in one folio of his illustrated book of Hours of Étienne Chevalier, which dates to about the same time as the diptych. Currently in the Condé Museum in Chantilly, the miniature represents a kneeling Chevalier together with his patron saint, who solemnly proffers a roughly shaped four-sided stone. The stone has mass (i.e. is perceived to be of substantial weight), and its surface is marked by faint ridges and crevices with a smooth golden-tinged edge. Another exception is a small wood sculpture dated c. 1525–1530 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The work of the German sculptor Hans Leinberger, this St Stephen is seated on a bench holding in his right hand an open book with three stones on top (Fig. 7). The stones look like carefully fashioned polygonals, thus conveying an allusion to human-flaked stone objects. Both the miniature and the sculpture are intriguing in suggesting a potentially modified stone, but neither is clearly diagnostic, and it is not possible to undertake the kind of analyses presented here.

Figure 7. Hans Leinberger's sculpture of St Stephen seated on a bench holding a book with three stones on top of it. The angular shape of the stones may be inferred to portray the properties of knapped stone, but it is difficult to comment on this in any detail. (Image used here under the Metropolitan Museum of Art's open access policy.)

In the Melun Diptych, Fouquet has rendered the stone as a very special object (detail, Fig. 1). Its red-to-brown colour, typical of patinated flint and millstone artefacts (Fig. 6), stands in marked contrast to the luxurious blue and red robes of the donor and the saint. Its large size, its shimmering surface sheen and the angular, jagged topography of the stone clearly suggest a geological outlier, a ‘wonder’ of nature. A fascinating result of an infrared reflectography analysis of the left panel reveals an under-drawing and an under-painting, and significant reworking of the jagged stone (Kemperdick Reference Kemperdick2018, fig. 96). The initial appearance of the stone in the under-drawing did not include the many detailed ridges and flake scars seen on the finished version, but it did already suggest some obvious attention given to its edges, along with some shaping. It is as if it was first rendered at a stage prior to the removal of the outer flakes and cortex (Supplementary Figure 2). Thus, the artist seems unknowingly to have repeated the stages of a handaxe's chaîne opératoire. This strikes us as one of the most interesting areas of revision and elaboration revealed by the recent technical analysis to which the panel was subjected (Kemperdick Reference Kemperdick2018, 143–9).

Did Fouquet understand the object he depicted to have been a curious natural phenomenon, potentially a ceraunia (Goodrum Reference Goodrum2002; King Reference King1867), or a part of the natural world modified by human hands, or, in a religious vein (Buettner Reference Buettner2022; Honour & Fleming Reference Honour and Fleming1982; Robertson & Hutton Reference Robertson and Hutton2021), a supernatural creation? The former and latter are not mutually exclusive. Although Fouquet's (and his patron's) understanding and intent are largely unknowable, it is plausible that the artist reproduced an Acheulean handaxe discovered locally in Tours, possibly by himself or someone in his immediate social sphere.

Certainly, the prominence of the ‘jagged rock’ in this religious context encodes some symbolic significance, perhaps imbued with a certain potency, and a link to the divine (Buettner Reference Buettner2022). Evidently Jean Fouquet saw something extraordinary in this object and chose to render it with as much precision and detail as that given to the jewelled crown of the Virgin or the perspectival architecture. The stone object emerges as more than an accidental instrument for the martyrdom of the saint and now becomes a sacred relic. It is very possible that the painter knew of a special stone in St Stephen's story (see Rotelle Reference Rotelle and Hill1994) and then chose an extraordinary object for its depiction. The special stone appears in one of the sermons of the theologian St Augustine in the fourth century, Sermon 323, which addresses the miracles of St Stephen in the Italian city of Ancona and mentions a local shrine honouring the saint (Rotelle Reference Rotelle and Hill1994, 162–3). Augustine mentions that some innocent people had been present at the stoning of the saint in Jerusalem. One of the stones bounced off the martyr's elbow and then landed at the feet of a pious man, who picked it up and brought it to Ancona. A revelation told him to deposit it there, and a shrine developed around the miraculous stone.

Handaxes could potentially have played social or religious roles in fifteenth-century France—be it for a very limited period or even only in Fouquet's regional (Tours) social sphere—but other sources of evidence are required to expand on these possibilities further. What is evident through the painting is that the handaxe-like stone had social significance, and as such, the painting now adds to our already complex understanding of the social implications of handaxes across Palaeolithic, historic and modern periods (Kohn & Mithen Reference Kohn and Mithen1999; Lycett et al. Reference Lycett, Schillinger, Kempe, Mesoudi, Mesoudi and Aoki2015; McNabb Reference McNabb2012; Pope et al. Reference Pope, Russel and Watson2006; White Reference White2022; Wynn et al. Reference Wynn, Berlant, Overmann, Coolidge, Overmann and Coolidge2019). We undertook the shape, flake scar and colour analyses here out of curiosityFootnote 1 and a shared fascination with the history of Palaeolithic archaeology and the field's epistemology. Identifying a fifteenth-century painting of a handaxe does not change what we know about Acheulean individuals. What our finding does do is push back securely attributed evidence for when Acheulean handaxes became part of the ‘modern’ social and cultural world. Moreover, it raises more questions about how and when these objects may have been incorporated into the cultural systems of earlier historical and prehistoric societies.

Acknowledgements

JC is supported by a doctoral training scholarship funded by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council. JDS would like to thank the Dartmouth College Montgomery Fellows Program, C. Musiba, N. Dominy and B. Pobiner. SK thanks Ada Cohen of the Art History Department at Dartmouth College for helpful conversations on the Melun Diptych.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774323000252