Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder that is characterised by impaired insulin secretion and poor response to insulin( Reference Miranda-Diaz, Pazarin-Villasenor and Yanowsky-Escatell 1 , Reference Willingham 2 ). Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) accounts for approximately 90 % of all patients with DM( Reference Willingham 2 ). Diabetic nephropathy (DN) affects approximately one-third of all patients with DM, and it is a major cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD)( Reference Chan and Tang 3 ).

Standard approach for management of DN includes control of blood pressure through the blockade of renin–angiotensin system (RAS) and glycaemic control; however, these interventions may not prevent the progression of DN to ESRD( Reference Chan and Tang 3 , Reference Gu, Yang and Qi 4 ). Thus, development of additional therapies to prevent progression of DN is a key research imperative.

Low-protein diet (LPD) has been designed to reduce protein overload and to ameliorate glomerular haemodynamics in patients with kidney disease( Reference Brenner BM and Hostetter 5 ). Indeed, the beneficial effects of LPD have been shown in various rodent models of kidney disease including DN( Reference Otoda, Kanasaki and Koya 6 , Reference Ran, Ma and Liu 7 ). However, definitive evidence of the clinical benefit of protein restriction in patients with kidney disease is yet to be obtained( Reference Piccoli, Vigotti and Leone 8 – Reference Noce, Vidiri and Marrone 10 ). Recently, Shah & Patel et al. ( Reference Shah and Patel 11 ) demonstrated that LPD could be prescribed to patients with slowly progressive CKD in the early stages (stages 1–3), but not to CKD patients in the late stages (stages 4 and 5). However, patients with DN were not included in this study. The effect of LPD therapy on nutritional status of patients with renal disease is a valid concern( Reference Noce, Vidiri and Marrone 10 ); this is particularly relevant in the case of patients with DN in whom impaired response to insulin leads to loss of body mass( Reference Otoda, Kanasaki and Koya 6 ). To reduce the risk of malnutrition due to LPD, use of a treatment strategy based on restricted protein intake in combination with administration of keto analogues of amino acids, to delay the progress of CKD, was assessed in several studies( Reference Kalantar-Zadeh, Cano and Budde 12 ). Ketoacids (KA) have excess N residues, which can be used for production of essential amino acids (EAA). Use of LPD supplemented with KA (LPD+KA) was shown to maintain muscle mass and decrease loss of body weight in a rat model of type 2 DN( Reference Huang, Wang and Gu 13 ). In a type 1 DN rat model, LPD+KA was shown to improve nutritional status and reduce urinary protein excretion as compared with that with LPD treatment alone( Reference Yang, Yang and Cheng 14 ). The beneficial effects of LPD+KA in type 2 DN, particularly at an early stage, are not yet known.

Histological changes including glomerular hypertrophy, mild mesangial expansion and thickening of the glomerular capillary walls can be detected as early as 2 years after the diagnosis of DM( Reference Mac-Moune Lai, Szeto and Choi 15 ). Microalbuminuria is a sign of early-stage DN, which appears before changes in serum creatinine levels( Reference Willingham 2 , Reference Molitch, DeFronzo and Franz 16 ). Early detection of DN and prevention of disease progression in the early stages is a key clinical imperative to forestall irreversible renal injury( Reference Miranda-Diaz, Pazarin-Villasenor and Yanowsky-Escatell 1 ).

Oxidative stress is a trigger for DN, which is caused by the hyperglycaemic status and the consequent renal accumulation of advanced glycation end products( Reference Forbes, Coughlan and Cooper 17 ). The imbalance in the redox state in DN is attributable to the increased production of oxidants or reactive oxygen species (ROS), which overwhelms the local antioxidant capacity( Reference Miranda-Diaz, Pazarin-Villasenor and Yanowsky-Escatell 1 , Reference Asmat, Abad and Ismail 18 ). The classical markers of oxidative stress include the products of lipid peroxidation (4-hydroxynonenal, malondialdehyde (MDA))( Reference Kumawat, Sharma and Singh 19 , Reference Fatani, Babakr and NourEldin 20 ) and protein carbonyl groups; these are abnormally expressed in DN( Reference Zheng, Wu and Jin 21 ). Oxidative-stress-induced pathological changes in DN such as albuminuria, proteinuria, glomerulosclerosis and tubule-interstitial fibrosis are mediated by multiple molecular signals( Reference Elmarakby and Sullivan 22 , Reference Domingueti, Dusse and Carvalho 23 ). Animal studies have shown that inhibition of oxidative stress attenuates the progression of DN( Reference Zhang, Wang and Yang 24 – Reference Wan, Hou and Zhou 26 ).

We previously found that the LPD+KA treatment displayed an additional antioxidant effect in 5/6 nephrectomised rats as compared with their counterparts treated with LPD alone( Reference Gao, Huang and Grosjean 27 , Reference Gao, Wu and Dong 28 ). It is not known whether LPD+KA treatment attenuates oxidative stress in DN. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the effect of LPD+KA in KKAy mice, which is a mouse model of early type 2 DN( Reference Soler, Riera and Batlle 29 ). We hypothesised that the LPD+KA exerts a renoprotective effect in early DN by reducing the degree of oxidative stress.

Methods

Experimental animals and treatment protocol

Male 8-week-old KKAy mice were obtained from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and male 8-week-old C57BL/6 J mice were obtained from the Second Military Medical University. All animals were maintained according to local regulations and guidelines. All mice were fed adaptively with the normal protein diet (NPD, 22 % casein protein) for 4 weeks. Subsequently, the KKAy mice were divided into three groups, which were administered different diets: NPD (n 10); LPD (LPD, 6 % casein protein; n 10); and LPD+KA (LPD+KA, 5 % casein protein added 1 % KA; n 10). C57BL/6 J mice were used as a control group and fed NPD. All diets contained the same amount of energy content (14·7 kJ/g), vitamins and minerals, and were formulated according to the recommendations of the American Institute of Nutrition for rodent diets (AIN-93G)( Reference Reeves 30 ). The diet formula is listed in Table 1. KA (α-ketoacids compound powder) were provided by Fresenius Kabi. The KA compound powder includes the following components( Reference Shah, Kalantar-Zadeh and Kopple 31 ): four KA analogues of the EAA (valine, leucine, isoleucine and phenylalanine); the hydroxyacid analogues of methionine; 4 EAA (lysine acetate, threonine, tryptophan, histidine) and l-tyrosine. The nutritional interventions lasted for 12 weeks and animals were killed at 24 weeks of age. The experimental protocol of the current study was approved by the Animal Care Committee at the Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China.

Table 1 Diet formula

NPD, normal protein diet; LPD, low-protein diets; LPD+KA, LPD supplemented with ketoacids.

Blood, urine and tissue sample collection

Blood and urine samples were collected at the age of 12, 16, 20 and 24 weeks. Before collection of blood samples, the mice were fasted for 6 h. Under short anaesthesia with diethyl ether (MB0678; Meilunbio), 300–500 μl of blood sample was obtained through the inner canthal orbital vein. Fasting blood glucose level was measured immediately using the blood glucose meter (ACCU-CHEK® Performa Nano; Roche). Blood samples were collected into serum separator tubes. After clot formation, the samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and serum was collected. Urine samples, 24 h, were collected with the use of metabolic cages. Urine samples were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The serum and urine samples were stored at −80°C before further processing. Albumin concentration in serum and 24-h urine was measured using a commercial ELISA assay kit (ab108792; Abcam) with a detection range from 1·56 to 400 μg/l by the colorimetric detection method (Micro-plate Reader-ST-360; Kehua). According to the product information and instructions, the calculated overall intra-assay CV is 4·5 %, and inter-assay CV is 9·9 %. Creatinine concentrations in serum and 24-h urine were measured using a commercial kit( Reference Wolley, Wu and Xu 32 ) (ab65340; Abcam) with a detection range from 4 to 20 μmol/l by the fluorometric detection method (SpectraMax i3x; Molecular Devices). According to the protocols( Reference Gai, Gui and Hiller 33 ), each sample was assayed for a minimum of two replicates, and duplicates were within 20 % of the mean value.

At 24 weeks of age, mice were anaesthetised by injection of sodium pentobarbital (70 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection, 1507002; Sigma) and were killed to collect kidney samples( Reference Ishikawa, Ito and Tanimoto 34 ). Half of the kidneys were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Some of the renal cortical tissues were fixed in 2·0 % glutaraldehyde (UFJ00964; Junruishengwu) and stored at 4°C; these were used for the examination of glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and podocytes under a transmission electron microscope (H-600; Hitachi)( Reference Ito, Tanimoto and Yamada 35 ). The remaining renal cortical and medullary tissues were frozen in liquid N2 for further protein analysis.

Histological analysis and electron microscopy

Paraffin-embedded renal samples were sliced into 3-μm sections with a pathological microtome (RM2135; Leica). The slides were stained using periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) kit (395B; Sigma) to evaluate glycogen deposition and mesangial expansion( Reference Pei, Okura and Nagao 36 ). The mesangial expansion was assessed in a blinded manner using a semi-quantitative analysis, as described elsewhere( Reference Wang, Shi and Wang 37 ). In brief, twenty cortical glomeruli cut at vascular pole per kidney were used for morphometric analysis. The amount of mesangial extracellular matrix was identified by PAS-positive material in the mesangium; the glomerular area was also traced along the outline of capillary loop using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics Inc.). The percentage of mesangial matrix occupying the selected glomerular tuft area was then calculated, and the relative mesangial area was expressed as a percentage of the glomerular surface area.

To measure the GBM thickness, three electron micrographs of non-overlapping fields were obtained for each glomerulus at a constant magnification of 10 000×. An average of ten points was measured per case, after which the arithmetic means with their standard errors for GBM thickness were determined for each animal( Reference Mac-Moune Lai, Szeto and Choi 15 ). Finally, the arithmetic means with their standard errors for each treatment group were calculated and recorded.

Protein analysis

Total renal (including cortex and medulla) tissues were homogenised using a homogeniser (Pro200, Bio-Gen Series; PRO Scientific Inc.) in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (1 µl/mg tissue, P0013B; Beyotime), which contains 1/50 (v/v) protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (P1045; Beyotime). Tissue homogenate was centrifuged at 12 000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected for further analysis. Total protein concentration was determined by the Bradford protein assay (P0006-2; Beyotime)( Reference Ernst and Zor 38 ).

The oxyblot protein oxidation detection kit (S7150; Chemicon International Temecula) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to assess the level of protein carbonyl groups( Reference Lee, Kwon and Kim 39 ). The level of oxidatively modified proteins was quantified and expressed as fold increase over that observed in normal controls via measurement of optical density using the Image lab 4 software (Bio-Rad).

For Western blot, the homogenate was subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted using a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and then incubated with the primary antibody against nitrotyrosin (NT) (ab110282; Abcam)( Reference Shu, Vivekanandan-Giri and Pennathur 40 ). The enhanced-chemiluminescence system was used to detect the signals.

The concentration of renal MDA was determined using a commercial kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (A003-1; Njjcbio). The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) (A001-1; Njjcbio) was measured as described by Gao et al. ( Reference Gao, Wu and Dong 28 ).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means with their standard errors. The Shapiro–Wilk comparisons normality test was used to assess the distribution of all variables. Comparisons for normally distributed data between two groups were conducted using two-tailed t test, and one- way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for non-parametric analysis when data were non-normally distributed. P<0·05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were carried out using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc.). Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism software version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Calculation of sample size was performed by using the ‘resource equation’ method, as described by Charan & Kantharia( Reference Charan and Kantharia 41 ).

Results

KKAy mice were treated with NPD, LPD or LPD+KA from 12 to 24 weeks of age. Wild-type C57BL/6 J mice treated with NPD from 12 to 24 weeks of age served as the control group.

Low-protein diet supplemented with ketoacids reduced albuminuria in diabetic mice.

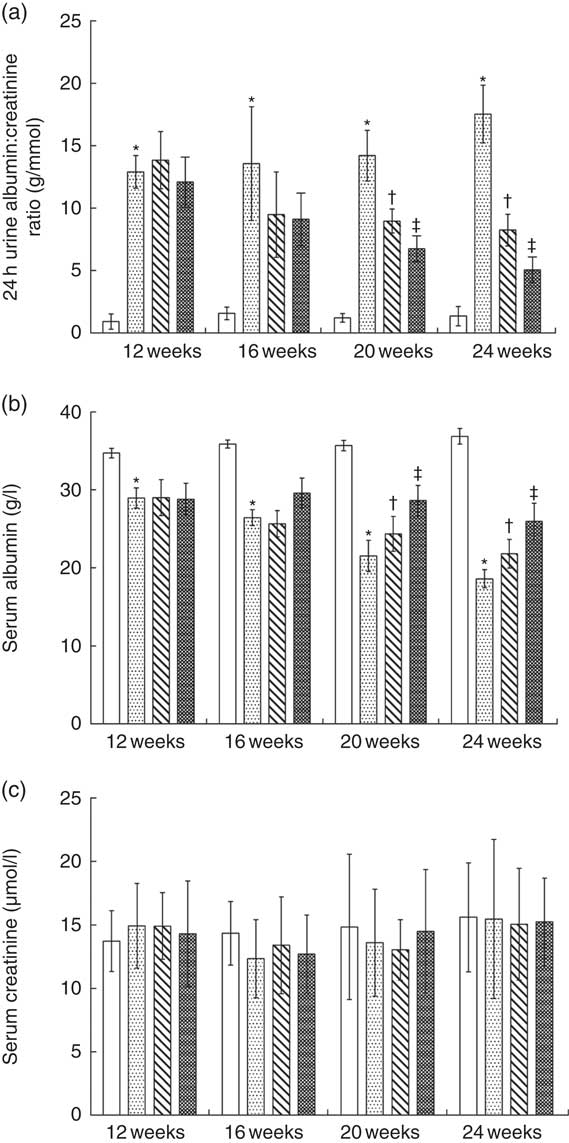

Fig. 1(a) shows that the ratio of 24-h urine albumin:urine creatinine in normal protein diet (NPD)-treated KKAy mice was significantly higher than that in control mice from 12 to 24 weeks of age. Treatment with LPD significantly reduced albuminuria in KKAy mice starting from 20 to 24 weeks of age; LPD+KA further reduced albuminuria at 20 and 24 weeks as compared with that observed with LPD treatment alone (Fig. 1 (a)). At 24 weeks, LPD+ KA treatment reduced the ratio of 24-h urine albumin:creatinine by 71 % as compared with that observed with NPD treatment (P=0·00002).

Fig. 1 Biochemical parameters of urine and serum in the experimental groups. ![]() , Control;

, Control; ![]() , normal protein diet (NPD);

, normal protein diet (NPD); ![]() , low-protein diets (LPD);

, low-protein diets (LPD); ![]() , LPD supplemented with ketoacids. * P< 0·05 v. control; † P < 0·05 v. NPD; ‡ P< 0·05 v. LPD.

, LPD supplemented with ketoacids. * P< 0·05 v. control; † P < 0·05 v. NPD; ‡ P< 0·05 v. LPD.

KKAy mice had significantly lower level of serum albumin compared with control mice from 12 to 24 weeks of age (Fig. 1(b)). LPD significantly increased serum albumin levels in KKAy mice from 20 to 24 weeks of age, as compared with that with NPD treatment (Fig. 1(b)). LPD+KA treatment further increased serum albumin levels in KKAy mice at 20 and 24 weeks of age (Fig. 1(b)). At 24 weeks of age, the LPD+KA treatment elevated the serum albumin level by 39 % as compared with that observed with NPD treatment (Fig. 1(b), P=0·003). No significant difference was observed between the four groups with respect to changes in serum creatinine level from 12 to 24 weeks of age (Fig. 1(c)).

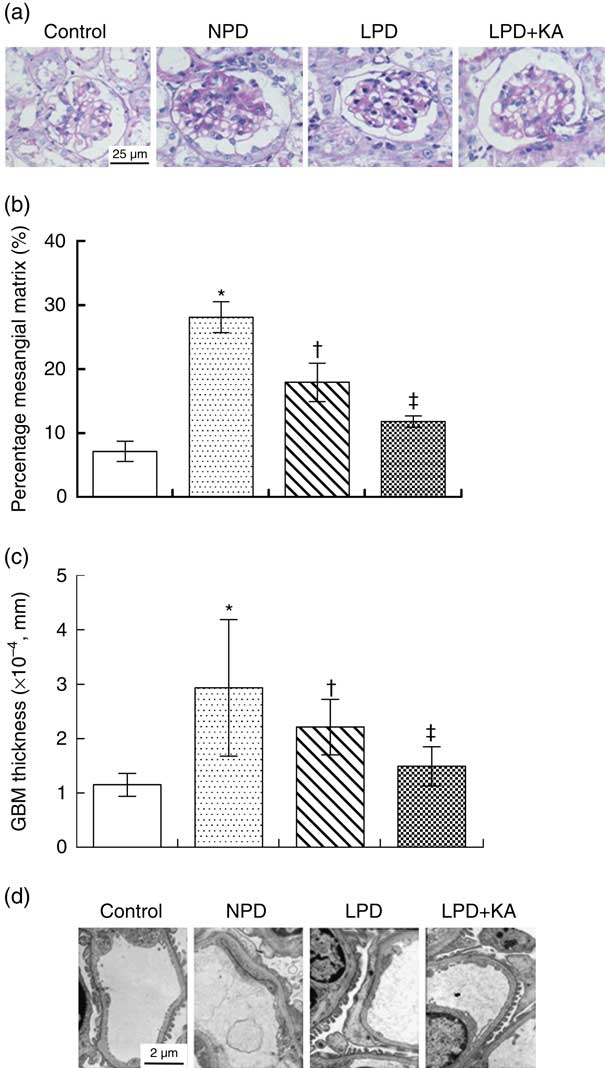

Low-protein diet supplemented with ketoacids prevented glomerular damage in diabetic mice.

PAS staining showed that the glomerular mesangial matrix was accumulated in KKAy mice at 24 weeks of age compared with control mice (Fig. 2(a)). The relative mesangial area was significantly reduced by 36 % by LPD treatment as compared with that observed in NPD-treated KKAy mice (Fig. 2(b), P=0·02). LPD+KA treatment reduced the relative mesangial area by 58 % as compared with that observed after NPD treatment (Fig. 2(b), P=0·02).

Fig. 2 Renal structural changes in KKAy diabetic mice after nutritional interventions. ![]() , Control;

, Control; ![]() , normal protein diet (NPD);

, normal protein diet (NPD); ![]() , low-protein diets (LPD);

, low-protein diets (LPD); ![]() , LPD supplemented with ketoacids (LPD+KA); GBM, glomerular basement membrane. * P< 0·05 v. control; † P < 0·05 v. NPD; ‡ P< 0·05 v. LPD.

, LPD supplemented with ketoacids (LPD+KA); GBM, glomerular basement membrane. * P< 0·05 v. control; † P < 0·05 v. NPD; ‡ P< 0·05 v. LPD.

The thickness of GBM and podocyte foot process was assessed by electron microscopy. The thickness of GBM was increased by 2·5-fold and podocyte foot process effacement was observed in KKAy mice at 24 weeks of age compared with control mice (Fig. 2(c) and (d)). The LPD treatment decreased glomerular basement thickness and improved the severity of the podocyte foot process effacement in KKAy mice; these beneficial effects were more profound in the LPD+KA group (Fig 2(c) and (d)). LPD+KA treatment reduced the thickness of GBM by 49 % as compared with that achieved with NPD treatment (P=0·03).

Low-protein diet supplemented with ketoacids did not change kidney weight and blood glucose levels in diabetic mice

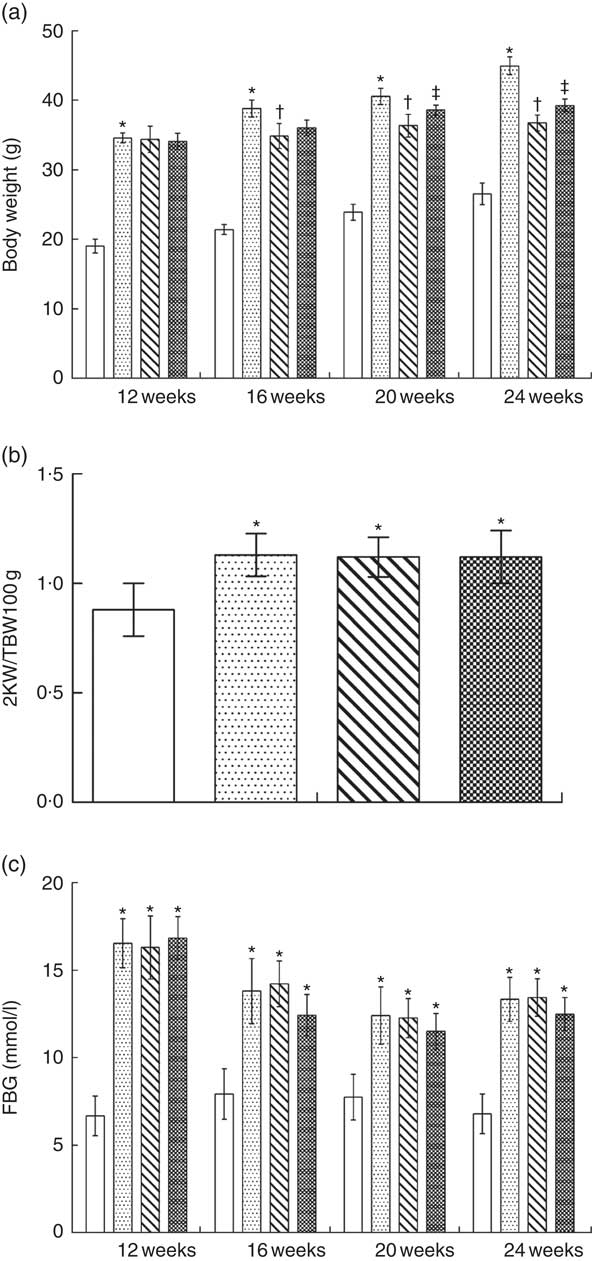

The total body weight of NPD-treated KKAy mice was significantly greater than that of control mice from 12 to 24 weeks; LPD or LPD+KA treatment reduced the body weight of KKAy mice from 16 to 24 weeks of age (Fig. 3(a)). The two kidney weight:total body weight (2KW:TBW) ratio was increased in the NPD-treated KKAy mice at 24 weeks of age compared with control mice; treatment with LPD or LPD+KA had no effect on the 2KW:TBW ratio (Fig. 3(b)).

Fig. 3 Kidney weight, body weight and blood glucose levels in KKAy diabetic mice after nutritional interventions. ![]() , Control;

, Control; ![]() , normal protein diet (NPD);

, normal protein diet (NPD); ![]() , low-protein diets (LPD);

, low-protein diets (LPD); ![]() , LPD supplemented with ketoacids; 2KW:TBW, two kidney weight:total body weight; FBG, fasting blood glucose. * P < 0·05 v. control; † P < 0·05 v. NPD; ‡ P < 0·05 v. LPD.

, LPD supplemented with ketoacids; 2KW:TBW, two kidney weight:total body weight; FBG, fasting blood glucose. * P < 0·05 v. control; † P < 0·05 v. NPD; ‡ P < 0·05 v. LPD.

Fasting blood glucose levels were measured throughout the treatment in all groups. Fasting blood glucose levels of KKAy mice were higher than those of control mice throughout the duration of the experiments; treatment with LPD or LPD+KA showed no effect on fasting blood glucose levels (Fig. 3 (c)).

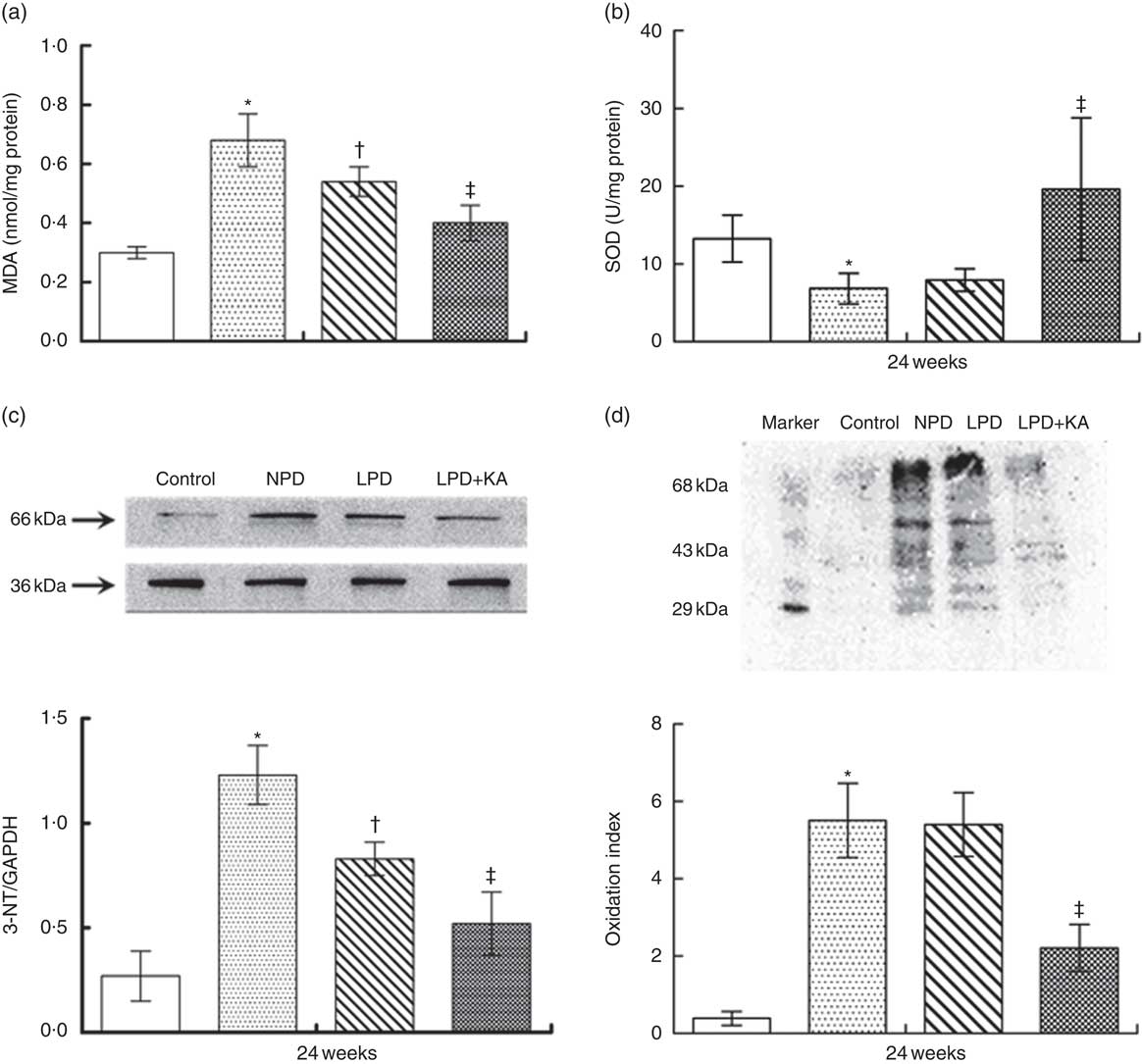

Low-protein diet supplemented with ketoacids ameliorated oxidative stress in diabetic mice

To evaluate oxidative stress in kidneys of rats with diabetes, the concentration of MDA and the activity of SOD were measured at 24 weeks. The levels of renal MDA in the NPD-treated KKAy mice were higher than those in the control mice. Treatment with LPD and LPD+KA significantly reduced the levels of renal MDA (by 21 and 41 %, respectively) as compared with that observed after NPD treatment (Fig 4(a), P=0·01). The activity of renal SOD in KKAy mice was lower than that in control mice (Fig. 4(b)). Interestingly, LPD treatment showed no effect on renal SOD activity (Fig. 4(b)). However, treatment with LPD+KA significantly increased renal SOD activity in KKAy mice (Fig. 4(b)).

Fig. 4 Amelioration of oxidative stress in KKAy diabetic mice by low-protein diet (LPD) and ketoacids (KA). ![]() , Control;

, Control; ![]() , normal protein diet (NPD);

, normal protein diet (NPD); ![]() , LPD;

, LPD; ![]() , LPD supplemented with KA (LPD+KA); MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; NT, nitrotyrosin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. * P< 0·05 v. control; † P< 0·05 v. NPD; ‡ P< 0·05 v. LPD.

, LPD supplemented with KA (LPD+KA); MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; NT, nitrotyrosin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. * P< 0·05 v. control; † P< 0·05 v. NPD; ‡ P< 0·05 v. LPD.

The oxidative stress was further evaluated by measuring the production of NT in the kidneys. Western blot analysis showed that the expression of renal NT in the NPD-treated KKAy mice was higher than that in the control mice. Treatment with LPD significantly reduced the renal NT expression, which was further reduced by treatment with LPD+KA treatment (Fig. 4(c)). Furthermore, results of oxyblot analysis revealed a 10-fold increase in carbonyl formation in kidneys of KKAy mice as compared with that in control mice, which suggests increased oxidative stress of proteins in KKAy mice (Fig. 4(d)). LPD treatment showed no effect on carbonyl formation; however, LPD+KA treatment significantly reduced carbonyl formation (by 60 %) as compared with that observed with NPD treatment (Fig. 4(d), P=0·002).

Discussion

KA have been prescribed alongside LPD to patients with CKD( Reference Aparicio, Bellizzi and Chauveau 42 ). Previous studies have shown that LPD+KA has more pronounced beneficial effects than those of LPD alone with respect to impeding the progression of CKD and in delaying the need to initiate kidney replacement therapy( Reference Garneata and Mircescu 43 ). Results of a meta-analysis suggest that protein diet restriction slows chronic renal disease progression in non-diabetic and type 1 diabetic patients, but not in type 2 diabetic patients( Reference Rughooputh, Zeng and Yao 9 ). Whether LPD+KA has beneficial effects in type 2 DN, especially in the early stage of DN, is not clear. In the current study, we focused on the effect of LPD+KA treatment in the early stages of DN, when the disease is still reversible. We showed that LPD retarded disease progression in an early type 2 DN mouse model; the beneficial effects of LPD were further enhanced by supplementation of KA. We also found that treatment with LPD+KA attenuated the degree of renal oxidative stress in KKAy mice.

Abnormal intra-glomerular haemodynamics contributes to the progression of DN. Protein overload is one of the several molecular mechanisms that are believed to underlie abnormal intra-glomerular haemodynamics in DN( Reference Otoda, Kanasaki and Koya 6 ). The renoprotective effects of LPD have been demonstrated in animal models of DN( Reference Ran, Ma and Liu 7 , Reference Yang, Yang and Cheng 14 ); further, positive results with use of LPD have been reported from several clinical trials on patients with DN( Reference Nezu, Kamiyama and Kondo 44 , Reference Koya, Haneda and Inomata 45 ). However, the results from human studies have not been consistent in different experimental settings( Reference Otoda, Kanasaki and Koya 6 , Reference Rughooputh, Zeng and Yao 9 , Reference Kiuchi, Ohashi and Tai 46 ). Protein overload activates the RAS, and LPD+KA has been shown to inhibit the intrarenal RAS( Reference Zhang, Yin and Ni 47 ). Giordano et al. ( Reference Giordano, Ciarambino and Castellino 48 ) found that a moderate-protein diet restriction (0·7 g/kg per d, 6 d/week) was successful in the management of DN in elderly individuals with T2DM. In our study, we demonstrated the renoprotective effects of LPD in T2DM as shown by reduced albuminuria and ameliorated glomerular damage.

However, the risk of malnutrition is a key concern with the use of LPD in patients with CKD( Reference Noce, Vidiri and Marrone 10 ); this is a particularly valid concern in patients with diabetes, in whom insulin deficiency can accelerate protein degradation( Reference Otoda, Kanasaki and Koya 6 ). LPD+KA has been shown to protect against malnutrition; for example, LPD+KA prevented muscle loss in 5/6 nephrectomised rats( Reference Wang, Lu and Shi 49 ). A study by Huang et al. ( Reference Huang, Wang and Gu 13 ) also supports the protective effect of LPD+KA against muscle loss in rats with DN. Compared with NPD, LPD was shown to decrease nitrogenous waste products( Reference Michael, Pedrini, Joseph, Chalmers and Wang 50 ) in the short term. However, long-term treatment with LPD was shown to enhance protein catabolism, which may lead to malnutrition; this is the most common complication of LPD treatment( Reference Noce, Vidiri and Marrone 10 ). KA have excess N residues that can be used for production of EAA( Reference Adeva, Calvino and Souto 51 ). Treatment with LPD+KA helps maintain neutral N balance by reducing protein catabolism and oxidation of amino acids( Reference Gao, Wu and Dong 28 ). Thus, we postulated that LPD+KA improves nutritional status in a mouse model of early type 2 DN, over and above that achieved with LPD treatment alone. In the current study, we found that the serum albumin levels were decreased in diabetic mice and were remarkably recovered by LPD+KA treatment, but only slightly recovered by LPD treatment. These findings suggest that supplementation of KA improved the nutritional status of diabetic mice. In addition, we found that supplementation of KA conferred an additional benefit in DN as shown by further reduced albuminuria and improved glomerular structure after LPD treatment.

We explored the renal protective mechanism of LPD+KA in a mouse model of early type 2 DN. In DN, there is an imbalance in the oxidant and antioxidant system, which leads to increased production of ROS( Reference Miranda-Diaz, Pazarin-Villasenor and Yanowsky-Escatell 1 , Reference Asmat, Abad and Ismail 18 , Reference Newsholme, Cruzat and Keane 52 ). Oxidation of important macromolecules including proteins, lipids, carbohydrates and DNA can be used as markers of oxidative stress( Reference Kumawat, Sharma and Singh 19 , Reference Elmarakby and Sullivan 22 ). Peuchant et al.( Reference Peuchant, Delmas-Beauvieux and Dubourg 53 ) found that very LPD+KA in chronic renal failure had an antioxidant effect. Indeed, a mild anti-oxidative effect of LPD was also observed in our study. KA have been shown to function as effective antioxidants and protect rat spermatozoa against exposure to H2O2 ( Reference Li, Liu and Zhang 54 ). In our previous study, supplementation of KA displayed renal protection against oxidative stress in 5/6 nephroctomised rat kidneys( Reference Gao, Wu and Dong 28 ). We therefore hypothesised that KA confer renal benefits through inhibiting oxidative stress in DN. This hypothesis was confirmed by our findings; LPD+KA treatment decreased production of renal MDA, reduced the expression of 3-NT and down-regulated protein carbonylation, alongside up-regulation of renal SOD activity in diabetic mice. These findings were either not observed or were observed to a lesser degree in diabetic mice treated with LPD alone.

The concentration of fasting blood glucose was assessed during the study, and we found that neither LPD nor LPD+KA treatment reduced the elevated concentration of blood glucose in diabetic mice, which suggests that renoprotective effect of LPD or LPD+KA treatment was independent of hyperglycaemia control.

KA compound powder was used as a supplement in our study and in several other animal experiments( Reference Zhang, Yin and Ni 47 , Reference Wang, Lu and Shi 49 ). However, the specific components of KA compound power, which are responsible for the renoprotective effect, are not known. KA supplements normally contain substantial amounts of 4-methyl-2-oxovaleric acid, the KA analogue of leucine (ketoleucine), which may suppress protein degradation( Reference Shah, Kalantar-Zadeh and Kopple 31 , Reference Meisinger and Strauch 55 ). KA supplements may also promote net protein anabolism and suppress urea formation, although the underlying mechanisms are not well characterised( Reference Meisinger and Strauch 55 ).

There are several limitations in our study. First, only four biomarkers for oxidative stress were measured in our study. More assays should be performed to fully characterise the antioxidant effect of LPD+KA in follow-up experiments. Second, the average daily consumption of feed for each mouse was not calculated, although the three kinds of diet used in this study contain the same number of energy content. Third, in the present study, we had only ten animals per group, which is a relatively small size. However, the number is large enough to ensure adequate statistical power by using the ‘resource equation’ method( Reference Charan and Kantharia 41 ), which is a crude method based on law of diminishing return. Although the method cannot be considered as robust as power analysis method, it is easy. Importantly, we first calculated the sample size with the software of NCSS-PASS 11.0 based on the thickness of GBM in this study. When sample size is nine, the power is 0·9283 and the effect size is 0·7012 (α=0·05, β=0·0717). We next calculated the sample size with the software of NCSS-PASS 11.0 again based on the result of urine protein, which was performed previously by Zhang et al.( Reference Zhang, Yin and Ni 47 ). According to this calculation, the statistic power is 0·92817 and the effect size is 0·701 (α=0·05, β=0·07183) when the sample size is nine. Thus, we believe that the same sample size (n 10) used in our experiment is large enough for statistical analysis.

Protein-restricted diets plus KA is considered as a valid therapeutic approach for patients with CKD( Reference Aparicio, Bellizzi and Chauveau 42 ). Our study showed that the renoprotective effect of LPD+KA in the early stage of type 2 DN is mediated by inhibition of oxidative stress.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81700579, 81670612) to C. M., the Three-year Project of Action for Shanghai Public Health System (GWIV-18) to C. M. and National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC0901502) to C. M.

C. M. conceived and coordinated the study. D. L. and M. W. wrote the paper. D. L., L. L., S. M., B. Y. and L. F. designed, performed and analysed the experiments shown in Fig. 1–3. D. L. and X. G. designed, performed and analysed the experiments shown in Fig. 4. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.