INTRODUCTION

The Friedenstein Palace in Gotha, Germany, holds under the inventory number Eth7R one of the most astonishing extant mosaic-encrusted Mesoamerican objects of its kind, at first sight apparently representing the head of a long-beaked bird. Despite its extraordinary craftsmanship, the artifact has been largely overlooked by scholars in the last 100 years, with the exception of a recent notable contribution (Schwarz Reference Schwarz2013) and its latest inclusion in an international exhibition and catalog on Aztec art (Berger Reference Berger, Berger and Castro2019). Based on a meticulous visual inspection of the object carried out by the authors in July 2019, this article provides additional information regarding the artifact's collection history and its possible identification and meaning, as well as new images and a detailed description facilitating a new understanding of the piece.

PRIOR REFERENCES AND STUDIES

The earliest direct record of a mosaic-encrusted bird's head sculpture in the Gotha collections is an entry in the second volume of the 1840 Inventarium der Herzogl. Kunst-Kammer auf Friedenstein. In the section on American objects, entry number 14 on page 64 reads: “The upper part of a bird's head, manufactured of mahogany and covered with pieces of turquoise, malachite, red coral, and mother-of-pearl” (Das Obertheil von dem Kopfe eines Vogels aus Mahagoniholz verfertigt und mit Türkisen, Malachit, rothen Korallen und Perlmutterstückchen besetzt) (Anonymous 1840: vol. II, p. 64). The entry also states the object had been recorded in a now-lost 1830 inventory of the same collection and it was “bought by valet Buttstädt in Rome.” The same description, together with the reference to the 1830 inventory (now stating that the object was recorded in entry 93, folio 58), is repeated in a later inventory of 1852. A few years earlier, in 1846, another Kunst-Kammer inventory was published by Bube (Reference Bube1846:68), in which the author stated, “Although it was bought in Rome, it probably originated from a Mexican idol,” thus asserting for the first time the correct cultural attribution of the artifact. Both the 1830 and 1840 inventories were carried out during the dukedom of Ernst I of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (1826–1844). Nevertheless, the references to valet Buttstädt and to Rome make clear that the arrival of the object in Gotha was related to his predecessor, Friedrich IV, who became Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg in 1822 and who, before that time, spent long periods of his life in Rome. We will return to this individual in the final section of the article on the provenance of the artifact.

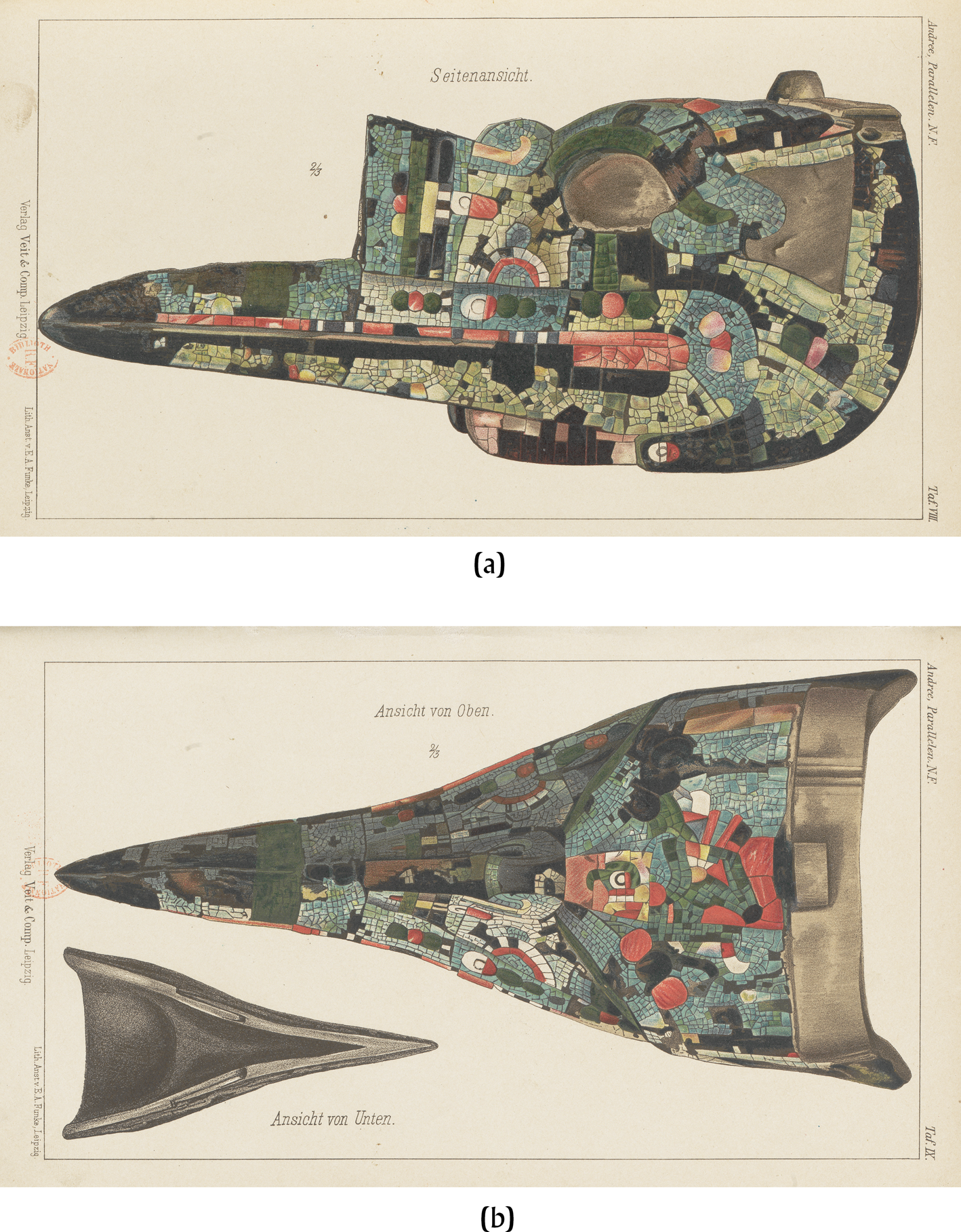

Given the thorough history of scholarly studies on the Gotha bird's head sculpture by Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2013), we offer only a brief synthesis. The earliest mention of the artifact specifically addressed to the Mesoamericanist community is from Italian paleoethnologist Pigorini (Reference Pigorini1885:3, n5) who, in an article on the mosaics he had just secured for his museum in Rome, stated that a similar one was “maybe in Gotha,” adding in a footnote that he was informed of the object's existence by [Augustus Wollaston] Franks—then at the British Museum's Department of Antiquities—but that he was unaware “if it really exists and where it is.” The sculpture was then described in detail by the geographer and ethnographer Andree (Reference Andree1888, Reference Andree1889, Reference Andree1890), who examined it thanks to the help of Aldenhoven, then Director of Gotha's Ducal Museum. In the 1889 publication, which includes two excellent color lithographs of the object (Figure 1), Andree (Reference Andree1889:129, Reference Andree1890:147) stated it “was brought by a valet of Duke Friedrich IV of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg in the first decades of our century from Rome and comes from the collections of the local Jesuits.” Andree (Reference Andree1889:128–129, Reference Andree1890:148) identified the artifact as the representation of a woodpecker or a crow, adding that the “stylized figure of a parrot” appears on the animal's forehead.

Figure 1. Lithographs of the sculpture known as the Bird Head published by Andree (Reference Andree1889): (a) Plate VIII, lateral view of the Bird Head; (b) Plate IX, top view and underside of the Bird Head.

Later references to the Gotha sculpture were penned by Oppel, Lehmann, Pogue, Saville, and Seler. The geographer Oppel (Reference Oppel1896), in an article on turquoise mosaics published in the Globus journal, reproduced a long, direct citation from Andree's Reference Andree1889 work and included a black-and-white drawing of the object clearly created after Andree's lithograph. Lehmann (Reference Lehmann1906:319) briefly mentioned the Gotha piece—again drawing on Andree's Reference Andree1889 work—in an erudite article also published in Globus, in which he speculated the Mesoamerican mosaics in European collections were some of the gifts received by Cortés and Juan de Grijalva from Indigenous elites. Pogue, in turn, succinctly referred to the bird's head in an article (Pogue Reference Pogue1912:445, 449), as well as in a book on turquoise (Pogue Reference Pogue1915:93, 95–96), repeating information from Andree's text and even publishing a black-and-white reproduction of one of Andree's Reference Andree1889 lithographs upside down. Saville (Reference Saville1922:48, 81) included another concise mention of the object in his famous book Turquois Mosaic Art in Ancient Mexico, where he published a new black-and-white drawing, arguably based again on Andree's lithographs (Saville Reference Saville1922:Plate XXXIVB). The following year, in a contribution on Mexican mosaics also drawing on Andree's work, Seler (Reference Seler and Seler1967 [1923]:365) simply stated that “the excellent piece in Gotha is a bird mask.”

After these early contributions, references to the Gotha bird's head have been quite cursory, some illustrated with the same color photo (e.g., Anton Reference Anton1986; Duyvis Reference Duyvis1935; Eberle Reference Eberle2010; Izeki Reference Izeki2008; Steguweit Reference Steguweit1985; Toscano Reference Toscano1984 [1944]). As far as we know, it was Toscano (Reference Toscano1984:179) who first affirmed in 1944 that the sculpture represented the Nahua Wind God—known as Ehecatl and Quetzalcoatl—as a “stylized bird head,” an identification that was not supported by a systematic iconographic analysis, but that was repeated by later authors without additional arguments (e.g., Izeki Reference Izeki2008:139; Schwarz Reference Schwarz2013:31–32). The relative oblivion into which this marvelous piece had fallen among Mesoamericanists finally ended with the above-mentioned study by Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2013), in which the author provided stimulating interpretive insights. Schwarz, who published two new photos of the object, also stressed the potential relevance of scientific analyses, which remain to be done in the future.

PHYSICAL FEATURES AND ICONOGRAPHY

Most authors who have discussed the Gotha piece simply state that it represents a bird's head, with no further indication of the avian species and its possible symbolism; only Andree (Reference Andree1889:128–129) has proposed it might be a woodpecker or a crow. Another line of interpretation identifies the object as the head of the Nahua Wind God, Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl. Our description and analysis of the physical features of the piece and its iconography enable us to provide a more thorough interpretation of it as a sculpted image of the Postclassic Nahua and Mixtec Wind God and culture hero—generally known in these societies as Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl and 9-Wind—as well as to characterize the specific aspects of this entity manifested in this particular representation. This in-depth study led us to request our colleague, an expert in archaeological art, Nicolas Latsanopoulos, to recreate the original appearance of the Bird Head sculpture in a series of drawings included in the present article. We invite readers to refer to them, with the caveat that, due to the fragmentary character of some sections of the mosaic, the proposed reconstruction is hypothetical in some respects and inspired by what we observed in the rest of the artifact (compare Figures 2–4).

Figure 2. Recreation of the original appearance of both sides of the Bird Head sculpture and top view. Drawings by Nicolas Latsanopoulos.

The sculpture is made of a single piece of wood (length = 30 cm, height including the top wooden knob = 13.5 cm, and width =16.5 cm), which presents a few cracks that were consolidated at some point, but remain visible on its inner surface and even in specific areas of its outer surface—for example, on the right side of the top of the head, from the back edge of the sculpture to the upper part of the eye socket (right and left are meant from the point of view of the bird, not of the viewer) (Figures 3, 5, and 6). Although the earliest available reference to the object (1840 inventory) states the wood is mahogany, it appears to be an unfounded guess; lack of scientific studies precludes the identification of the origin of the wood support. Furthermore, it is worth remembering that analyses of other Mesoamerican mosaic-encrusted wood sculptures in the British Museum revealed that most of them were carved of Cedrela odorata, with two exceptions: a shield made of Pinus sp. and a small animal head carved of Erythrina coralloides (Cartwright et al. Reference Cartwright, Stacey, McEwan, King, Carocci, Cartwright, McEwan and Stacey2012:7–12; McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:35). The visual appearance of the Bird Head's wood suggests it could be Cedrela odorata.

Figure 3. Right side of the Bird Head sculpture. Photograph by Domenici ©Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.

The outer surface of the wood piece was carefully carved to create a shape suggesting a bird head with a long, sharp bill in the front, with anthropomorphic and fantastic features (Figures 3 and 4). A prismatic protuberance topped by a volute starts between the eyes and projects on top of the bill. The eyes, in turn, were deeply cut in the wood's surface making it so thin that it cracked in the lower part of the left eye socket, where a tiny fragment of wood is now missing (Figures 4 and 7a). Other parts of the head, for instance the eyebrows, the edges of the bill, and the “lips” were also delicately outlined through woodcarving. The top of the head is crowned by a flat wooden bar, devoid of any mosaic, with a trapezoidal knob in the center. On the right side, this bar has a notch that might have resulted from a blow to the piece, which probably produced the above-mentioned crack. At the back of the head, just below the edges of the wooden bar, there is a perforation on each side (Figures 3–5). The piece of wood was cut out in its interior to produce a concave opening when seen from below or the back. The inner surface was roughly hewn and shows the wedge-shaped marks left by the sculptor's tools (Figure 6), as in other sculptures of this kind (McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:40). Given the hollowed out opening in the back, the artifact has been repeatedly interpreted as a mask as discussed below, but the hollow part is far too narrow and not at all flat as to allow its placement on a human face (Figures 6 and 8).

Figure 4. Left side of the Bird Head sculpture. Photograph by Domenici ©Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.

Figure 5. Right side of the Bird Head sculpture, detail of the eye, temple, and flat wooden bar with a notch. Photograph by Domenici ©Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.

Figure 6. The Bird Head sculpture seen from the back. Photograph by Domenici ©Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.

Figure 7. Details of the left side of the Bird Head sculpture: (a) the eye socket; (b) the back of the head; (c) section with pink tesserae at the bottom of the head; (d) tesserae and pigments on the front edge of the wood bar at the back of the head; (e) and the mosaic under the eye. Photographs by Domenici ©Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.

Figure 8. The carved interior of the Bird Head sculpture. Photograph by Domenici ©Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.

Almost the entire outer surface of the wood was covered in mosaic. The 1840 inventory indicates it was made of turquoise, malachite, red coral, and mother-of-pearl. Although the constituent materials of this piece have not been scientifically analyzed, clearly the green palette of the mosaic includes turquoise and some of the various minerals known as cultural turquoise (such as chrysocolla, azurite, amazonite, etc.; Weigand Reference Weigand1993:300–303; Weigand et al. Reference Weigand, Harbottle, Sayre, Earle and Ericson1977:16), as well as malachite, materials often found in other Late Postclassic mosaics (McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:27–30; Melgar Tisoc et al. Reference Tisoc, Emiliano, Ciriaco and Desruelles2018; Stacey et al. Reference Stacey, Cartwright, Verri, McEwan, King, Carocci, Cartwright, McEwan and Stacey2012; Thibodeau et al. Reference Thibodeau, Luján, Killick, Berdan and Ruiz2018). The turquoise and/or cultural turquoise are in two tones—a light green and a bright blue-green—while the malachite creates darker zones of green. The light-green and brilliant blue-green gemstones cover most of the sculpture. The light tone tesserae are irregular in size and shape and cover peripheral areas of the object, filling areas in between forms, thus constituting a sort of background (Figures 7b and 9a). By contrast, the vibrant blue-green tesserae and the dark green ones are smaller, generally square, forming harmonious mosaics principally used to create the designs that compose the figure, as discussed below. Apart from its less meticulous craftsmanship, the light-green mosaic sections are also the areas where we detected a reused tessera—specifically on the left side of the protuberance (Figure 4).

Figure 9. Details of the right side of the Bird Head sculpture: (a) the back of the head; (b) the curved part of the lips and tooth; (c) the tip of the bill. Photographs by Domenici ©Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.

Beyond green gemstones, the mosaic includes other materials that make the sculpture not only polychrome, but also a multimedia artwork (Caplan Reference Caplan2019:14–15; Domenici Reference Domenici2020), which involves shells and organic substances. Based on our visual inspection, we posit that the red tones were not obtained from coral as proposed by early observers; instead, we suggest these tesserae were made of Spondylus sp. shells, as in other Mesoamerican mosaic pieces (Cartwright et al. Reference Cartwright, Stacey, McEwan, King, Carocci, Cartwright, McEwan and Stacey2012:12; McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:32–34; Velázquez et al. Reference Velázquez Castro, Arellano and Maldonado2014). These tesserae were primarily employed to create specific motifs, as well as the background highlighting an important figure on the forehead (Figure 10a). We have detected two red tones in the Gotha Bird Head. An intense red was used to create the lips seen on the bill, the background of the forehead figure, and various other details, while a lighter tone, tending to pink, was applied on the lower parts of the piece (Figures 3, 4, and 7c). The mosaic also displays two types of white tesserae: a lustrous yellowish white that can be tentatively identified as mother-of-pearl (Pinctada mazatlanica), and a matte white (Figures 5 and 11), which is probably Strombus sp. based on results from scientifically analyzed specimens (Cartwright et al. Reference Cartwright, Stacey, McEwan, King, Carocci, Cartwright, McEwan and Stacey2012:12; McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:32–34).

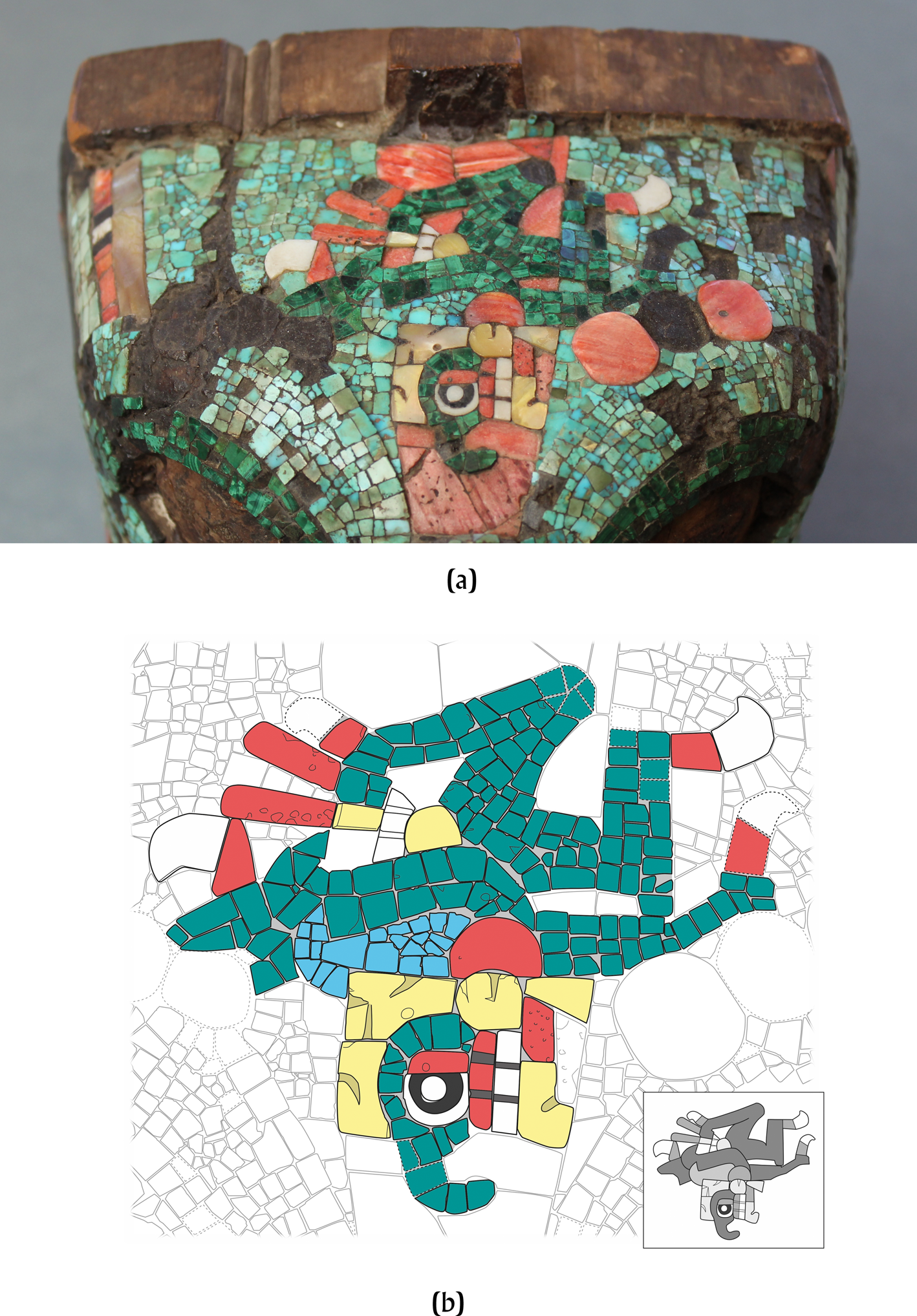

Figure 10. Detail of the forehead and top of the head of the Bird Head sculpture. (a) Photograph by Domenici ©Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha. (b) Drawing by Nicholas Latsanopoulos.

Figure 11. Detail of the right side of the Bird Head's protuberance. Photograph by Domenici ©Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.

Finally, the mosaic on the artifact includes two types of blackish materials. One appears only in a small black-and-white motif repeated several times on the piece (Figures 5, 9b, and 11). Its appearance is dull and from what is known from other mosaics it might be lignite (McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:30). The second blackish material is clearly not mineral in origin and is actually a very dark brown substance with golden reflections, which served to create the fan-shaped areas behind the figure's eyes (Figures 3, 4, and 9a). We believe it might be an application of the adhesive used to make the mosaic, which is seen in the parts where the tesserae are lost. It is worth remembering that on other mosaic-encrusted objects, a resin (in one instance mixed with beeswax) was used to shape three-dimensional details, perhaps originally covered with gold leaf, as on one of the masks and the shield in the British Museum (McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:50, 64). Andree (Reference Andree1889:129) suggested the adhesive employed to create the mosaic on the Gotha sculpture might have been asphalt, but analyses performed on similar artworks revealed a predominance of resins extracted from Pinaceae, at times mixed with copal resins extracted from Burseraceae (Bursera sp.; Protium sp.) and beeswax (McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:35–37, 40–41; Pecci and Mileto Reference Pecci and Mileto2017; Stacey et al. Reference Stacey, Cartwright and McEwan2006). A specific group of Mixtec mosaics shows the use of a visually different material, a gritty cement containing conifer resin, at times mixed with different kinds of wax (Berger et al. Reference Berger, Moreau, Lemaitre, Martinez, Sears and Seig2021; Domenici Reference Domenici, Martinez, Sears and Seig2021a; McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:37; Montero Reference Montero1968; Newman Reference Newman2002; Saville Reference Saville1922:76).

In addition to the polychrome and multimedia character of the gemstone and shell mosaic, the Gotha head exhibits minute pigment remains. We observed traces of a blue-green pigment on the front edge of the flat wooden bar on top of the head, inside and below an eye socket, and on the inner surface of the piece, while a white pigment was applied in the interstice between the figure's lips. In some instances, the blue-green pigment appears where tesserae were once applied, suggesting its visibility may be due to the loss of the tesserae and the adhesive. This is the case of the wooden bar at the back of the head, which consists of exposed wood except for the narrow frontal edge that was originally covered with blue-green tesserae (Figure 7d). The situation of the figure's right eye is comparable, since we noted a tiny trace of blue-green pigment on its lower edge and a blue-green tessera stuck on its upper edge (Figure 5). This evidence coincides with historical testimonies, which describe objects encrusted with mosaics first being painted, for the artists who applied the gemstones and shells to follow the guidelines outlined with pigments on the wood support (e.g., Toscano Reference Toscano1984:174–175). Interestingly, traces of paint—with pigments such as cinnabar, red ocher, and indigo-based Maya blue—in areas not covered by mosaic have been detected on other specimens (McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:47, 50, 53). Additionally, on the lower part of our sculpture, the adhesive used to affix now missing Spondylus tesserae shows a reddish coloration, but we cannot say if the glue was colored or if a red pigment was applied beneath the adhesive; a similar reddish coloration under a missing Spondylus tessera has been noted on the mosaic-covered Yacatecuhtli mask at the Museo delle Civiltà in Rome (Domenici Reference Domenici2020). For comparative purposes, it is worth recalling that hematite-colored resins were used to attach the teeth of a mask and the double-headed serpent in the British Museum; in those cases, such material was probably aimed at representing the red gum between the teeth (McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:50, 57).

At first sight, the most remarkable element of the Gotha sculpture is certainly the bird's bill that spans three quarters of the artifact's length. Its delicate mosaic decoration is primarily based on a pattern of alternating bands of green tones that differs on the upper and lower parts of the bill—that is, above and below the lips—and that is not strictly symmetrical on the right and left sides of the head. On the rear “half” of the bill, the upper part has four bands—more or less rectangular—of blue-green and light-green mosaic, which alternate in a neat chromatic rhythm, but are not symmetrical on the two sides of the object (compare Figures 3 and 4). In this upper section, the work is particularly meticulous: the tesserae are often nearly squared, and most are smaller than those on the lower part—as in the rest of the mosaic, however, the blue-green tesserae are decidedly smaller than the light-green ones (Figures 3, 4, and 9b). In contrast, light-green tesserae predominate in the lower section of the bill where the irregularity in tesserae size and shape stands out. The pattern of bands is subtler here, for light-green bands alternate with darker and somehow multicolor bands, in which a predominantly light-green mosaic is spotted with dark green and blue-green tesserae (Figures 3, 4, 7c, and 9b). In general, the lower part of the bill and the peripheral zones of the piece display less care in their execution, as illustrated, in particular, by the size and shape of the tesserae. In fact, the darker bands in the lower part of the bill were perhaps manufactured with the leftover tesserae after the creation of the principal sections of the object.

On the front “half” of the bill, the decoration increases in complexity, incorporating bands of malachite that along with the bands of blue-green and light-green tesserae create the following chromatic pattern: blue-green, dark green, light green, blue-green, dark green (Figures 3, 4, and 9c). The preservation of these tesserae bands deteriorates moving toward the tip of the bill: only one tessera remains in the last band of malachite on the left side and a few on the right side, while the end of the bill is now completely bare (Figure 9c). Our close examination of the object, however, revealed that on the immediate edge of the last—almost completely lost—band of malachite, the remaining adhesive retains traces of the tesserae that were once affixed there. If we follow the chromatic pattern created by the bands of different green tones in this section of bill, this last band of tesserae should have been light green, a hypothesis consistent with the large size of the marks left by the missing tesserae on the adhesive. The very tip of the bill, in contrast, does not hold any clue that could lead us to determine its original appearance; however, the color sequence observed in this section again suggests it might have been covered by blue-green tesserae.

Besides its band decoration, the bill of the Gotha sculpture also had red (Spondylus), black (lignite?), and white (mother-of-pearl and Strombus shell?) tesserae, introducing some naturalistic features in this section, while enhancing the beauty and impact of the whole piece, for this masterful blend of materials turns it into a veritable polychrome masterpiece. In particular, large elongated Spondylus tesserae—virtually all lost on the lower part of the bill, although their marks remain on the adhesive—represent the lips (Figures 3, 4, 9b, and 9c). This red portion of the mosaic thus outlines the figure's mouth, which is almost closed with only a narrow interstice dividing the upper and lower lips, where we observed vestiges of a white pigment. We should emphasize that although the mouth is particularly long—and remarkable in the object, due to the chromatic contrast between the green tesserae of the bill and the red of the lips—it does not reach the tip of the bill. In fact, the last and almost completely lost bands of tesserae originally wrapped themselves like ribbons around this protruding tip, without any interruption by the red tesserae of the lips—although, in this section, the interstice between the lips was carved and is still visible in the wood support (Figures 3 and 9c). At the other end of the bill, connecting the upper and lower lips, curved segments of red mosaic are made of a unique semi-circular Spondylus tessera on the right side and three triangular ones on the left side (Figures 3, 4, and 9b).

Right beside these curved sections, the lower part of the mouth has wider zones of irregular red tesserae evoking gums where teeth were added below (Figures 3, 4, and 9b). Only one of the teeth was preserved on the right side of the head, but thanks to the marks visible on the adhesive we know that three of them were originally placed on each side. The remaining tooth is made of a unique tessera of white shell that exhibits a vertical incision on the lower part (Figure 9b). This said, while the irregular appearance of these red sections of the mosaic evokes the texture of gums, the original rows of three teeth seem to emerge, in a counterintuitive way, from the lower edge of the lower lip/gum, instead of being placed over it as one would expect. In our view, this should be interpreted as a stylistic convention, since a similar configuration is seen on the Copenhagen Xolotl head, pertaining to the same stylistic “family” of mosaics (Domenici Reference Domenici2020). Additionally, the intentional use in these specific sections of the mouth of small, irregular Spondylus tesserae instead of the usual, rectangular elongated ones might suggest another identification. Indeed, this technical detail, as well as the apparently erroneous representation of the teeth beneath the lower lip, lead us to suggest that these red sections over the teeth do not represent gums or part of the lower lip, but rather the sagging, scalloped edge of the upper lip, which is a distinguishing trait of Ehecatl (Figure 12b), also seen on Xolotl, for example in the Codex Borgia (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plate 65).

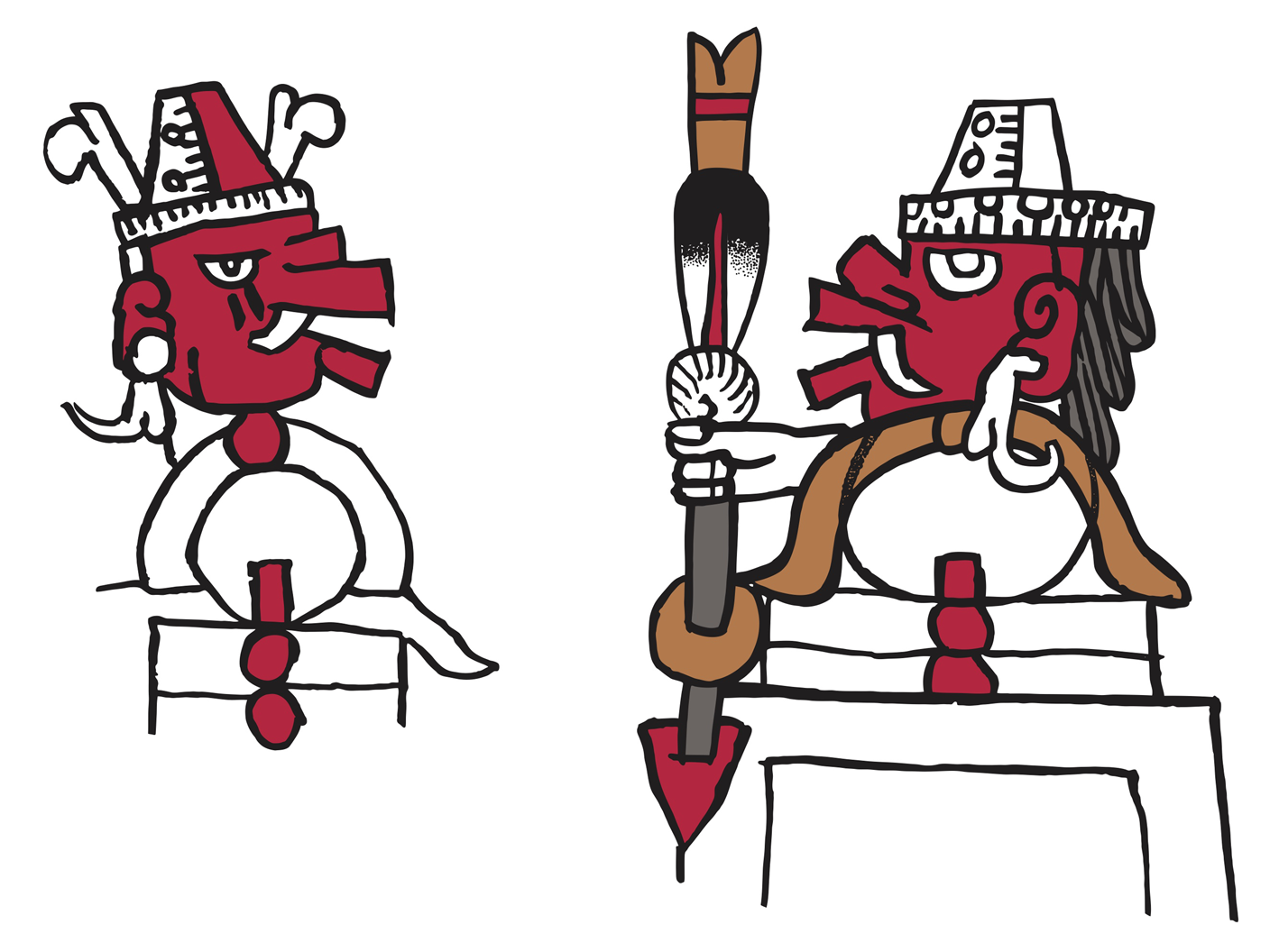

Figure 12. The god Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl in Postclassic Nahua imagery. (a) Full-length Wind God statue from Calixtlahuaca. (b) Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl, Codex Borgia, Plate 19, detail. (c) Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl, Codex Laud, Plate 23, detail. Drawings by Nicolas Latsanopoulos. (d) Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl, Codex Borbonicus, Plate 22, detail. ©Bibliothèque de l'Assemblée nationale, Paris. (e) Face of Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl in the “manta del ayre,” Codex Magliabechiano, f. 7v, detail. Drawing by Nicolas Latsanopoulos. (f) Priest or human embodiment of Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl, Codex Borbonicus, Plate 26, detail. ©Bibliothèque de l'Assemblée nationale, Paris.

Moving toward the front part of the bill, after these sections of sagging lips and teeth, both sides of the sculpture display small areas in which all the tesserae are lost (Figures 3, 4, and 9b). The marks on the adhesive, however, reveal that these areas perhaps included another series of tesserae referring to the flaccid upper lip of Ehecatl—because these sections are of similar dimensions to those of the preserved areas discussed above—and a large single tessera. On the left side, it had a rectangular shape and might have been another tooth, but on the other side of the head the mark left by the corresponding tesserae shows a puzzling large rounded shape (Figure 9b). Other enigmatic sections are the rectangular areas at the very bottom of the head, slightly behind the bill. These areas were encrusted with large irregular pinkish tesserae that are almost completely lost on the right side of the head and fortunately better preserved on the left side (Figure 7c); the adhesive where the mosaic is missing shows a reddish hue.

As we have shown, the multiple colors and diverse materials used in the decoration of the Gotha Bird Head served to outline naturalistic features, while they transformed the piece into a polychrome work highly valued and prized by its creators (Dupey García Reference Dupey García2021). This polychromy is the hallmark of a specific style in extant mosaic objects—probably developed in a specific region, period, or by certain artistic schools or workshops—that is represented in only one of the “family” of mosaics held in early European collections (Domenici Reference Domenici2020). Moreover, not only the multimedia and polychrome character of the Gotha mosaic-encrusted sculpture, but likewise some specific motifs in its decoration are found in this specific “family” of Postclassic, central Mexican mosaics. This is the case of three ornamental designs employed along the bill: the polychrome series of disks, the stellar eye, and what we call the black-and-white motif. The polychrome series of disks, which the senior author interpreted elsewhere as qualifying the object as “precious” (Domenici Reference Domenici2020), can cluster two, three, and even four round tesserae—or, more rarely, groups of tiny tesserae that form disks—made of different materials and colors, some of which are missing today. The lower part of the bill presents groups of only two disks. In the upper part of the bill, where the decoration is richer, a missing series of disks was originally located on the ridge, right in front of the prismatic protuberance, while others are placed right above the upper lip, in what seems to be a continuous line of disks following the shape of the bill (Figures 3 and 4). A closer look at this section, however, reveals that each series of three or four disks is included in a specific band of the green toned mosaic (Figures 3, 4, 9a, and 9b), thus increasing the complexity of this decoration with the introduction of other media, multiple colors, and the various manifestations of shine generated by the gemstones and shells.

Sometimes, one of the disks in these polychrome series is replaced by a more complex motif that is well-known in Postclassic imagery and commonly called “stellar eye.” On the bill, it appears as part of the series of disks on the upper lip (Figures 4), but it also occurs alone, for example in the dark green mosaic “ribbon” at the tip of the bill (Figure 9c). The stellar eye is round or oval in shape and is composed of a red “half” made of Spondylus and a white “half” made of shell, in which a three-quarter circle is traced in black (Figures 3, 4, and 9b). In the Gotha Bird Head as well as in other mosaic-encrusted objects from the same stylistic “family,” this three-quarter circle was incised into the white shell and filled with a black substance, probably the adhesive used to glue the tesserae. This manufacturing technique, already noted by McEwan and colleagues (Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:76) on a knife in the British Museum, is clearly visible in those instances where the adhesive filling is completely or partially lost, revealing the carved groove (Figures 9b, 9c, and 11). The third decorative motif on the Gotha sculpture—as well as on other mosaic-encrusted artworks of the same “family”—is one that we call the black-and-white motif, for it alternates small black-and-white square tesserae in a line, usually two white ones made of shell and three black ones, perhaps made of lignite. Interestingly, this black-and-white motif, which the senior author tentatively interpreted elsewhere as qualifying the marked areas as “shiny” (Domenici Reference Domenici2020), is always inserted in red lines of Spondylus tesserae (Figures 3–5, 9b, and 11). On the figure's lips, this pattern is repeated twice on each side; in one instance, on the right side of the head, only a single black tessera is still in place. In these cases, the black-and-white motif probably alludes to the wet, and thus shiny, surface of the lips.

Another exceptional component of the sculpted figure, highly significant for its identification, is the prismatic protuberance between the eyes, projecting upward and forward reaching the middle of the bill (Figures 3, 4, and 11). In terms of ornamentation, it is mainly organized in two sections. On the front section, the symmetry between both sides is striking and the decoration is again based on a series of bands, juxtaposing from front to back: a band of tiny blue-green tesserae, a band of small and almost-square dark green tesserae, a band of elongated mother-of-pearl tesserae, a band of elongated Spondylus tesserae—within which is inserted, on each side, the black-and-white motif—and another band of blue-green tesserae. In this section, few tesserae of the red and white bands of Spondylus and mother-of-pearl have survived, while the turquoise and malachite mosaics stand out for their masterful execution, probably the finest in the piece (Figure 11). At half of their height, these vertical bands display some of the decorative elements characteristic of the piece: the black-and-white motif, the stellar eye and a series of three contiguous disks—on the left side, the series juxtaposes mother-of-pearl, Spondylus, and mother-of-pearl, a composition which is inverted on the right side, where we find Spondylus, mother-of-pearl, and Spondylus. Finally, the narrow, trapezoidal front of the protuberance was encrusted with a mosaic composed of small, almost-square, blue-green tesserae, which is now severely damaged with only the lower area intact, where a round tesserae, also lost, was originally placed.

The back sides of the protuberance, closer to the eyes, bear particularly interesting motifs. At the top, a mother-of-pearl volute is surrounded by a blue-green mosaic, on top of which a disk-shaped tessera was originally encrusted. On the left side of the head, the mother-of-pearl volute is bigger and made of two tesserae, while on the right it was created from a single tessera (Figures 4 and 11). As for the lower zones of both sides of the protuberance, where it joins the bill, they exhibit a semi-circular motif elaborated with two concentric lines of tesserae, one of white shell and the other of Spondylus. The interior of this half circle is filled with blue-green tesserae and a disk-shaped mosaic of the same material is placed on top of it. The “background” of all these motifs is a mosaic of light-green tesserae (Figure 11).

The protuberance over the bill and several elements of its decoration are critical for the figure's identity. In fact, a sharp bill associated with a rectangular protuberance projecting toward the front is typical of multiple painted and sculpted images of the Postclassic Nahua and Mixtec Wind God—principally known as Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl and 9-Wind (Figure 12)—who was one of the principal demiurges and culture heroes in these societies. The prominent buccal mask, as it is often called, of this divine character has been described since early colonial times, and the sixteenth-century Codex Tudela, in particular, stresses that the Wind God gave rise to the wind when he blew through this appendage (Batalla Rosado Reference Batalla Rosado2002:f. 42). More recently, scholars have studied how the Mesoamerican Wind God's bill matches the physical features of different birds, especially ducks, whose habitats and conduct also connect them to the wind (Espinosa Reference Espinosa Pineda and Torres2001; O'Mack Reference O'Mack1991; Taube Reference Taube2004:169–173). While it is likely that the Wind God's images were inspired by different animals, it is worth noting that Whitley (Reference Whitley1973), followed by Pohl and Lyons (Reference Pohl and Lyons2010:85), identified the deity's protuberance on top of the bill as a trait of the Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata), characterized by a prominent red caruncle over its bill. Interestingly, the Muscovy duck emits a hiss-like vocalization whose blend of breath and sound might have been equated with the Wind God's gusts by Mesoamerican peoples, who also consumed this animal either wild or domesticated (Gade Reference Gade, Kiple and Ornelas2000; Whitley Reference Whitley1973).

The Gotha sculpture is of little help in further clarifying the identification of the Wind God with a specific bird, but it is striking that the protuberance on the figure's bill is crowned by a volute that is clearly a reference to the wind (Dupey García Reference Dupey García2020; Espinosa Pineda Reference Espinosa Pineda1997; Taube Reference Taube, Fields and Zamudio-Taylor2001), as well as to the Wind God's ability to blow the wind through his bill. The mother-of-pearl volute, indeed, suggests that from the “block” formed by the bill and its protuberance the wind is blown and flows upward. Significantly, a similar volute can be observed on top of the buccal mask of well-known Wind God stone sculptures, such as the Coronation Stone of Moctezuma II (McEwan and López Luján Reference McEwan and Luján2009:69) or the full-length statue from Calixtlahuaca (Estado de México, Mexico) now on display in the Museo de Antropología e Historia de Toluca (Figure 12a). As for the half circles composed of lines of white shell and Spondylus tesserae and filled with a blue-green mosaic on the lower part of the protuberance (Figure 11), they also confirm the identification of a Wind God's image whose creation was aimed at evoking blowing air in multiple ways (Dupey García Reference Dupey García2020). In fact, the representations of this deity in many pre-Columbian Mixtec and Borgia Group manuscripts are figures in which the bill's protuberance is separated from the bill and converted into the god's nose, whose essential function of breathing is accentuated by the addition of nostrils (Figures 12b and 12c; Anders and Jansen Reference Anders and Jansen1994:Plates 1, 6, 23, 32; Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Jiménez1992a:Plates 10, 24, 31, 34, 36, 38, 47, 48, Reference Anders, Jansen and Jiménez1992b:Plates 38, 65, Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plates 9, 40, 51, 72, 73, Reference Anders, Jansen and García1994a:Plates 24, 35). In these images, the nostrils are depicted as quarter circles and positioned in the same location as the half circles in the Gotha artifact; consequently, we interpret the latter as possible representations of the god's nostrils from which he exhaled air.

The identification of the Gotha sculpture as an image of the Wind God is further strengthened by the analysis of other decorative elements displayed in the piece. In particular, the blue-green mosaic disks on top of both “nostrils” may be explained on the basis of several representations of the Nahua and Mixtec Wind God in stone or gold and painted in manuscripts. Indeed, in the Calixtlahuaca sculpture (Figure 12a), the pair of “Atlantean” sculptures found on the Calle de las Escalerillas in Mexico City, or the squatting sculpture in the Museo Nacional de Antropología also in Mexico City, the deity exhibits two tubular appendages on the sides of his bill's protuberance, which might refer to the air blown by the Wind God from his “nares.” This proposal is supported by depictions of Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl in the codices Magliabechiano and Tudela, and also in a Mixtec gold earplug, where a tubular form topped by a precious bead emerges from the god's nostrils (Figure 12e; Anders Reference Anders1970:ff. 7v, 11v, 61r, 78r; Batalla Rosado Reference Batalla Rosado2002:ff. 42r, 49r, 88r; McEwan and López Luján Reference McEwan and Luján2009:102). These “tubes” could be reminiscent of the chalchihuitl nose-plug that horizontally crossed the nose of Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl in pre-Hispanic codices, such as the Codex Borgia (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plates 9, 23, 56, 60), although we are not certain that they are depictions of this specific jewel. Rather, we regard both the horizontal nose-plug and the tubes along the protuberance/nose of the Wind God as variations of a widespread Mesoamerican visual metaphor: the materialization of precious breath emitted from the nostrils (Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:141–152). And we posit that the depiction of such tubes on the two-dimensional mosaic of the Gotha sculpture could have taken the form of disks.

Other diagnostic elements are the rows of white teeth, which are seen in an image of Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl in the Codex Borbonicus (Figure 12d; Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1991:Plate 22), while in this and other codices the god frequently displays a bill full of sharp teeth or a single canine protruding in the bill commissure (Figures 12b, 12c, and 12e; e.g., Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1991:Plate 5, Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plate 19). Finally, if we are correct in interpreting the section of uneven Spondylus tesserae over the rows of three teeth in the Gotha Bird Head as the typical scalloped, sagging edge of the upper lip of Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl—as depicted, for example, in the Codex Borgia (compare Figures 3 and 12b; Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plates 16, 19, 72)—this might be another one of the god's distinctive features.

The eye areas in the Gotha sculpture have two, almond-shaped eye sockets carved out of the wood support (Figures 3, 4, and 7a), which are now devoid of any decoration except for a tiny, blue-green tessera on the upper edge of the figure's right eye socket (Figure 5). This unique trace, already noted by Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2013:36), suggests that the edges of the eyes were once decorated with small blue-green tesserae. Otherwise, we have no clue regarding the original elements in the eye sockets. It is probable, however, that large pieces of brilliant materials, such as pyrite, were placed there and outlined by a thin, blue-green mosaic decoration. Such an arrangement would be similar to that of the mosaic-encrusted human skull today in the British Museum, where two pyrite orbs are delineated by pieces of white Strombus shell. Colonial accounts, such as Díaz del Castillo's (Reference Díaz del Castillo and Maudsley1956:219–220; Bassett Reference Bassett2015:146) chronicle, confirm that sculptures of the Nahua gods could be “covered with precious stones, and gold and pearls, and with seed pearls stuck on with a paste” and had “eyes that shone, made of their mirrors,” which were made of pyrite or obsidian. The hypothesis of large elements used in the eyes is also reinforced by the complete loss of the decoration of the two eyes—with the exception of the minuscule, blue-green tessera. Andree (Reference Andree1889:129) suggested that the original ornaments might have been purposely detached because of the value they had for the piece's former owners. Other hypotheses could also be raised, such as the insertion of eyes during the manufacture of the Nahua gods’ embodiments to give them identity and agency (Bassett Reference Bassett2015), and conversely their possible removal when their human creators wanted to inactivate them.

Below each eye, we again discern a decoration composed of a series of parallel bands, reminiscent of the band or bands sometimes seen under the eye of Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl—or crossing it—in the codices Magliabechiano and Tudela (Figure 12e; Anders Reference Anders1970:ff. 7v, 11v, 61r, 78r; Batalla Rosado Reference Batalla Rosado2002:ff. 42r, 49r, 88r). Close to the protuberance, two of them are still visible: a blue-green band, well-preserved on both sides, and a dark green one. In contrast, the two bands in the middle are completely lost today, but their existence is confirmed by the marks left on the adhesive (Figure 7e). Near the outer corner of the figure's left eye another line of blue-green tesserae is still visible (Figures 4 and 7e). Assuming that the pattern of parallel vertical bands seen on the protuberance is repeated under the eye, the two missing bands of mosaic might have been made of elongated mother-of-pearl and Spondylus tesserae, whose preservation is precarious throughout the piece.

Above the eye sockets, the Bird Head exhibits thick double eyebrows. The inner part is formed by a volute made of a dark green malachite mosaic, while the outer section is an even larger volute of blue-green tesserae that coils around the inner volute at the outer corner of each eye (Figures 3–5). This naturalistic element is also crucial for the identification of the figure, since a prominent blue eyebrow is one of the distinctive features of the Wind God in several Pre-Columbian and colonial manuscripts (Figure 12b). It is even found in some synoptic forms of the deity's image representing the day sign ehecatl (wind) in several codices, which include the bill and the protuberance/nose, the god's volute-shaped ear pendants, a single white fang protruding in the bill commissure, and a prominent blue eyebrow (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1991, Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b, Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993c, Reference Anders, Jansen and Van Der Loo1994b).

The back of the head is decorated on each side with an uneven mosaic of light-green tesserae (Figures 3, 4, 7b, and 9a), while on the “jaws” the craftsmanship of the mosaic involved other materials, perhaps another series of bands, as suggested by the marks left on the adhesive. On the left side, malachite is clearly seen flanking a vertical band without tesserae but still visible on the adhesive; on the right side, the situation is more confusing because a few malachite and blue-green tesserae remain, as well as the marks of the former bands of mosaic, again visible on the adhesive, but the distribution of colors is unclear (compare Figures 3 and 4). These peripheral areas also display some of the motifs typical of the Gotha sculpture and the “family” of mosaic-encrusted objects to which it belongs. A stellar eye was included on each “jaw” (Figures 3, 4, and 9b), while each “cheek” shows a series of disks. Specifically, two disks, now lost, were originally placed on the right side of the head, while, on the left, a design inspired by a series of three disks stands out for its irregularity because it is made of various tesserae of different shapes and sizes (Figure 7b).

Behind each eye, the figure exhibits a large, fan-shaped area that was filled—possibly after being outlined by a previous incision—with a dark brown organic material, most likely the adhesive employed to attach the tesserae (Figures 3, 4, and 9a). The application of this substance creates a contrast between the sheen of the stone and shell mosaic and the opaqueness, though with golden reflections, of the adhesive layer; a contrast that probably heightened the appreciation of this multimedia object. Perhaps this unexpected decorative use of the adhesive also had a symbolic meaning and was intended to suggest that this fan-shaped element filled with an organic material stood for another fan made with organic components. Specifically, we wonder if these designs on the back portions of the Gotha Bird Head represent the Wind God's fan-shaped neck ornament, often fashioned with dark and red feathers (Figures 12b and 12c). In fact, the neck ornament and the decoration made with the adhesive share their shape and location. Furthermore, on the right side of the Bird Head, the fan-shaped element ends with small trapezoidal areas of dark green malachite mosaic, each with an added red tip made of a single Spondylus tessera (Figure 9a). These mosaic additions to the decoration made with the organic material create a trapezoidal form with flaring tips that recall the composition of dark feathers and sparkles of red characteristic of the Wind God's neck adornment (compare Figures 9a and 12b). Additionally, in the Gotha sculpture, the colors of the fan-shaped element match those of Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl's neck ornament in the codices Laud and Ixtlilxochitl, in which it displays the same hues: black, red, and green or blue-green (Figure 12c; Anders and Jansen Reference Anders and Jansen1994:Plate 23; Durand-Forest Reference Durand-Forest1976:f. 103r). Curiously, the pattern of dark green mosaic and red tesserae is conspicuous for its absence on the left side of the Bird Head, making the sculpture notably asymmetric in these areas (compare Figures 3 and 4).

Last but not least, the top of the head and the forehead of the Gotha artifact display a central anthropomorphic figure rendered in a colorful mosaic on a background made of especially large Spondylus tesserae (Figure 10). In the first place, the placement of this figure is meaningful, since in most of the known anthropomorphic and zoomorphic Late Postclassic mosaics—for example, the Yacatecuhtli mask today in the Museo delle Civiltà in Rome, or the masks from the Tehuacán region (Puebla, Mexico) in the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC—the forehead shows some kind of chromatic “enhancement,” usually darker than the rest of the “face” (Domenici Reference Domenici2020, Reference Domenici2021b). Given the relevance of the forehead as one of the key bodily parts for the expression of the self in Mesoamerican systems of thought (cf. Classic Mayan baah, “forehead,” “face,” “body,” “portrait”; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:12, 58–72), the forehead of the Gotha Bird Head could have served as an appropriate functional locus (Salazar Reference Salazar Lama2014; Salazar and Valencia Rivera Reference Salazar Lama and Rivera2017), where an image that expressed some essential quality of the Wind God was displayed.

The red forehead area is bordered by bright blue-green tesserae on both sides. This visual contrast might have further emphasized the particular significance of this section's iconography, which required an exquisite mosaic of tiny blue-green tesserae, instead of the irregular composition of light-green stones normally used for peripheral areas or to create backgrounds. Enclosed in these blue-green areas we notice a series of three disks on each side, two of which were made of Spondylus on the left, while all are lost on the right (Figure 10a). On the outer edges of these blue-green areas, that is, at the “temples,” we see a new series of bands, exceptionally well-preserved on the right side: a white band of mother-of-pearl and a red band of Spondylus, where the black-and-white motif was inserted (Figures 5 and 10a).

We will describe and explain the anthropomorphic figure in the center as seen from the front because this is how it needs to be read in order to unveil its profound meanings (Figure 10). It is a descending figure typical of Postclassic Mesoamerican iconography: the bent legs are depicted at the top of the bird's head, while the diminutive character's head was designed on the Wind God's forehead, suggesting that the figure is falling headlong. Its limbs were rendered with a delicate malachite mosaic that originally ended with claws denoted by the combination of a Spondylus tessera with a hook-shaped white shell tessera. One of the legs is bent toward the back and the other on the front suggesting movement. The left arm is extended on the side of the figure and originally ended in a claw, now lost, which probably included the same white hook attached to a red base that we see on the right side. Most of the right arm, in contrast, is covered by a pair of large, nestled volutes made of blue-green turquoise and malachite, which stand for the torso of the figure (Figure 10b). The torso area also displays a Spondylus pectoral and a dorsal ornament with two narrow pendants created with tesserae of different colors and shapes. The two nestled volutes, which cannot be associated with any known body adornment, emphasize the twisted appearance of the descending figure.

The most exciting part of the falling anthropomorphic figure is undoubtedly the head, which is tipped backward to look up. It is made of a malachite mosaic and clearly shows an ear with an adornment composed of a trapezoidal pendant, both made of mother-of-pearl. The top of the small figure's head also displays two mother-of-pearl tesserae that were carved with curled notches to suggest curly hair. Two series of three minuscule Spondylus and shell tesserae were finely combined to create the gums and teeth of the small figure, which does not have lips and thus displays a fleshless jaw. A stellar eye is seen above the gums, while a mother-of-pearl volute is placed under the teeth, suggesting that the figure is exhaling, blowing, or speaking. Finally, the front part of the head—where the nose should be—exhibits a relatively long and curiously hooked appendage, also made of malachite (Figure 10). Due to this unusual “nose,” the small figure on the forehead was initially identified as a bird with a curved bill, the “stylized figure of a parrot” according to Andree's (Reference Andree1890:148) work, where one of the lithographs shows an appendage more pointed and bill-like than it really is (compare Figures 1 and 10). Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2013:37), however, has noted that the figure is not actually a real bird because he has limbs. At the same time, Schwarz has highlighted its aggressive features, such as the claws that might connect this character to several categories of harmful beings in Nahua culture. In particular, Schwarz succinctly compared the small figure on the Wind God's head with the Tzitzimime deities—specifically, the one depicted in the Codex Magliabechiano (Anders Reference Anders1970:f. 76r)—and the Cihuateteo, women who had died in childbirth and were transformed into menacing supernatural beings.

Clearly the small figure on the Gotha sculpture's forehead has a fierce appearance, based not only on its claws but also on its fleshless mandible displaying the teeth. The descending position with the head tipped backward is also interesting, since, in Mesoamerican mythology and iconography, it symbolizes the descent of different types of beings from upper regions of the cosmos, often to attack human communities or as part of cosmogonic narratives. But among the categories of descending beings, the hooked frontal appendage makes the Gotha figure virtually unique. In our view, this protuberance seems too thin and blunt to represent a bird's bill, while its shape is quite unusual for a nose in Mesoamerican iconography. Interestingly, though, beings with similar hooked noses—sometimes coiled, when the hook is rolled onto itself—are seen in the Borgia Group codices, particularly in the enigmatic central section of the Codex Borgia. In this series of plates, as well as in the Codex Cospi, the figures with hooked—or coiled—noses exhibit the same fleshless lower mandible, tangled and curly hair, and claws like the Gotha figure (Figures 13a, 13c, and 14b; Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plates 29, 31, Reference Anders, Jansen and Van Der Loo1994b:Plates 1–8). Also, the hooked-nose figures in these codices can wear a white ear adornment made of unspun cotton that has the same trapezoidal shape as the ear pendant of the forehead figure (Figure 13c). Finally, in some images in the Cospi, the hair of these beings has the same light color, while, in one instance, this manuscript shows the hooked-nose creature in a descending position with bent legs on the top and the head tipped backward on the bottom (Figure 13a; Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Van Der Loo1994b:Plate 2). Therefore, we believe that the aggressive-looking figure on the Gotha sculpture might be an expression of a hooked-nose supernatural being that is also seen in these codices. Identifying this being or category of beings is hence critical to understanding why he/she crowns the mosaic-encrusted head of the Wind God and to formulate hypothetical overall interpretations for the piece.

Figure 13. Hooked-nose entities and descending figures. (a) Codex Cospi, Plate 2, detail, Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, Ms.4093 ©Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna—Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna. (b) North mural of the side court, Palace IV, Mitla, Oaxaca, detail, from Seler (Reference Seler, Thompson, Richardson and Bowditch1991 [1888]:vol. 2, p. 186). (c) Codex Borgia, Plate 32, detail. Drawing by Nicolas Latsanopoulos.

Figure 14. Hooked-nose entities and wind-related figures in an emergence scene. (a) Codex Borgia, Plate 29. (b) Codex Borgia, Plate 29, detail of the frame goddess's face. (c) Codex Borgia, Plate 29, detail of the emergence of a figure with the buccal mask of the Wind God. Drawings by Nicolas Latsanopoulos.

INTERPRETATION

The Birth of the Wind God or His Descent as a Tzitzimitl

The interpretation of the descending hooked-nose figure on the Wind God's forehead can be supported by a review of the so-called “central section” of the Codex Borgia (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plates 29–46), where creatures with the same nose appear, as well as recurrent figures in falling position. Furthermore, although the content and meaning of the section have been the subject of long-standing debate, what is beyond doubt is that Quetzalcoatl is constantly depicted and evoked in these 18 plates of the Borgia (Nowotny Reference Nowotny2005 [1961]:266; Seler Reference Seler1963 [1904–1909]). It is unlikely that the joint reference to descent and to these two supernatural figures—Quetzalcoatl and the being with the curious hooked nose—both in the Gotha sculpture and in the Codex Borgia is a coincidence. For this reason, we will examine the occurrences of hooked- or coiled-nose characters in the central section of this manuscript in an attempt to shed light on their identity and the nature of their relationship to Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl.

The complexity and uniqueness of the central section of the Borgia have given rise to distinct interpretations since the early twentieth century. Following Seler (Reference Seler1963 [1904–1909]:vol. 2, pp. 9–61), several authors have agreed on the narrative quality of the section (see a summary in Boone [Reference Boone2007:171–173]), on the grounds that the protagonists on different pages seem to move from one page to another. Boone (Reference Boone2007:171–210), in particular, has argued that it is a narrative of creation, full of emergence scenes in which Quetzalcoatl, in his multiple guises, plays a central role as one of the major demiurges of Postclassic Nahua and Mixtec cosmogonies. Boone (Reference Boone2007:175–176) also analyzed the presence of hooked- and coiled-nose beings in this section of the Borgia—without dwelling on the curious shape of these appendages, though—where they appear as the structural elements that organize the different episodes of the narrative, first in the form of quadrilateral frame deities and then as strip goddesses (Figures 13c, 14a, and 14b). Summarizing earlier studies, Boone explains that such entities exhibit the features of Death and Earth divinities—in particular, skeletal mouths, tangled hair, and claws instead of hands and feet—while the iconography of the strip goddesses’ skirts alludes to darkness, sacrifice, and creation (Boone Reference Boone2007:176–177, 266). Following in Nowotny's (Nowotny Reference Nowotny2005 [1961]:266–267) footsteps, Boone also underscores that these supernatural beings organize the narrative's episodes and ensure continuity between them. Through the series of bands that form their bodies or through their cut open torsos different figures cross in a descending posture—in several cases, they are manifestations of Quetzalcoatl—and appear to be leaving one scene and entering the next (Figures 13c and 14a).

In the same vein, others scholars have proposed that the strip goddesses in the central section of the Borgia could be images of the sky and its different levels, or of celestial elements such as the Milky Way, and have suggested that the protagonists that pass through these bodies could be circulating between different parts of the cosmos, in particular descending from the Sky to the Earth (Díaz Reference Díaz and Díaz2016; Jansen and Pérez Jiménez Reference Jansen and Jiménez2017:450; Milbrath Reference Milbrath and Miller1988:162–163; Nowotny Reference Nowotny2005 [1961]:267; Seler Reference Seler1963 [1904–1909]:vol. 2, pp. 40–41). Regardless, it is interesting to note that the forehead figure on the Gotha piece—perhaps because of the limited space available for the construction of the image—blends the traits of deities whose bodies are crossed and descending figures that pass through these bodies into a unique being. Indeed, the falling figure on the Bird Head shares a hooked nose with the frame deities and strip goddesses of the Borgia and the two volutes—one nestled inside the other (Figure 10)—that compose the small figure's torso are structurally reminiscent of the repetition of motifs—particularly, spirals and sequences of fleshless ribs—that creates the frame goddesses’ bodies in the Borgia (Figure 14a). In other words, this unusual creature apparently merges the identities of two categories of supernatural protagonists seen in the Borgia's narrative: one that crosses and one that is crossed. As a consequence, the small figure on the Gotha piece perhaps refers to the action of descending or passing from one sector of the cosmos to another. This proposal is strengthened by a fragment of the mural paintings of Palace IV at Mitla, where a character in the same position and with curly hair similar to the small figure on the forehead, as well as a facial painting that recalls the distribution of colors on the face of the Wind God clearly descends headfirst from the sky (Figure 13b; Seler Reference Seler, Seler, Förstemann, Schellhas, Sapper, Dieseldorff and Bowditch1904:313, Reference Seler, Thompson, Richardson and Bowditch1991 [1888]:186).

There are, of course, several lines of interpretation to explain why a descending figure with several features of a hooked-nose being was depicted on the forehead of this Wind God sculpture. A first hypothesis we would like to consider is the small descending figure as a reference to the birth or rebirth of this god, for in Mesoamerica, and particularly in Nahua and Mixtec cultures, birth was conceived of as a descent (Milbrath Reference Milbrath and Miller1988; Olivier Reference Olivier, García and Mazzetto2021). Interestingly, in the previously mentioned Mitla mural, the figure with curly hair and possibly the facial painting of the Wind God is emerging headfirst from a V-shaped cleft in the sky in the typical form of a womb in Postclassic imagery (Milbrath Reference Milbrath and Miller1988:155–158); he is also grasping a rope that could be a reference to an umbilical cord (Figure 13b). Furthermore, in the central section of the Codex Borgia, the birth of Quetzalcoatl is evoked twice in a scene where the deity is falling headfirst, exactly in the same posture as the forehead figure (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plate 32; Boone Reference Boone2007:183–185; Díaz Reference Díaz and Díaz2016:92). In plate 32, the god first emerges from the mouth-womb (Milbrath Reference Milbrath and Miller1988:160) of a flint knife, placed on the navel of an anthropomorphic figure depicted in birthing position and, second, from the wound-womb (Milbrath Reference Milbrath and Miller1988:160) of the first strip goddess with a coiled nose seen in the narrative—in this part of the composition, Quetzalcoatl is flanked by two flint knives also placed in the body opening (Figure 13c). Beyond the allusion to descent, we know these images refer to the birth of the deity because Quetzalcoatl's emergence is associated with flint knives, a common mythical motif for deities’ origins in Nahua and Mixtec cosmogonies. A Nahua narrative tells that the primordial goddess gave birth to a flint knife, which was dropped from the sky and gave rise to several gods (Mendieta Reference Mendieta1993:77–78), while imagery displays the birth of Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, and 9-Wind from flint knives (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Jiménez1992a:Plate 49, Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plate 32; Nicholson Reference Nicholson1978:66–68; Nowotny Reference Nowotny2005 [1961]; Pohl Reference Pohl1998), one of which was created by a couple of deities with skeletal mouths and claws (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993a:179).

Additionally, in the first scene of the Borgia's central narrative (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plate 29), a dark figure with claws, a fleshless mouth, and a tiny hooked nose also stands in a parturient pose and orchestrates the emergence of a mass of darkness (Boone Reference Boone2007:179–181; Díaz Reference Díaz and Díaz2016:79), from which, in turn, serpentine forms with the iconographic features of the night and the wind come forth, as well as beings of different colors with the Wind God's buccal mask (Figures 14a and 14c). Although the interpretation of such a complex image is of course challenging, we are probably viewing an origin scene that involves a creative entity with a hooked nose and death traits who gives birth to beings associated with the wind. In the lower part of the scene, two black creatures with the Wind God buccal mask—who emerge from night and wind serpents—also cross in a headfirst posture through the cut open body of a hooked-nose quadrilateral god to enter the following part of the narrative (Figure 14a). In sum, what we see on these pages of the Borgia (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plates 29 and 32) are wind-related protagonists—in plate 32, the Wind God himself in a descending posture—being born or emerging from hooked- or coiled-nose beings (other examples are seen on the remaining pages of the section). As a consequence, the fusion of both characters on the forehead of the Gotha Wind God sculpture might be an allusion to the birth of the deity, evoked here through the metaphor of descent and a reference to the being from whom Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl is born, according to the cosmogonic events seemingly depicted in the Borgia.

Other significant elements of the scene in Borgia 29 are the two ropes coming from the skeletal creature with the tiny hooked nose, who seems to be creating multiple wind-related beings (Figure 14a). Indeed, we have seen that in the above-mentioned Mitla mural, the figure emerging from a “womb” in the sky and descending headlong also grasps a rope (Figure 13b), while in the cosmogony painted in the Codex Vienna, Quetzalcoatl was born from a flint knife, and descended from the sky using a rope—in this case, the god is not shown falling headlong but walking; however, he is framed by two figures who descend headfirst (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Jiménez1992a:Plate 48). In the Codex Borgia (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plate 29), the beings descending on ropes are spiders (Figure 14a), which should be interpreted as Tzitzimime in this context (Anders and Jansen Reference Anders and Jansen1996a:48–49, Reference Anders and Jansen1996b:f. 3r; Seler Reference Seler1901–1902:51–52, Reference Seler1963 [1904–1909]:vol. 2, p. 22), a category of deities traditionally identified as descending creatures (Quiñones Keber Reference Quiñones Keber1995:f. 4v; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1953–1982:bk. VI, p. 37, bk. VII, pp. 2, 27, bk. VIII, p. 2; Thevet Reference Thevet and Jonghe1905:28). Thus, the creation of wind-related beings was associated with the descent of the Tzitzimime on ropes in plate 29 of the Borgia, in the same way that, in plate 48 of the Vienna, the birth of Quetzalcoatl from a flint knife is followed by his descent on a rope from the sky to the earth.

This interpretation makes sense because, according to the Codex Telleriano Remensis (Quiñones Keber Reference Quiñones Keber1995:ff. 4v, 18v), Quetzalcoatl was one of the large group of the Tzitzimime divinities, some of whom were the children of the primordial couple and were identified as air deities (Alvarado Tezozómoc Reference Alvarado Tezozómoc, Migoyo and Chamorro2001:176, 262), but who also stand out for their ambivalent and changing nature (Klein Reference Klein2000; Pohl Reference Pohl1998). Following the seminal work of Thompson (Reference Thompson1934), the junior author of this article has analyzed their ambivalent participation in Nahua mythology (Dupey García Reference Dupey García2010), at times as creators of the world who saw to its stability—as sky bearers (Alvarado Tezozómoc Reference Alvarado Tezozómoc, Migoyo and Chamorro2001:176, 180, 262, 291; Boone Reference Boone1999; López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin and Luján2009:450–461)—and who were providers of all sorts of natural and cultural goods, and at other times as the destroyers of life on earth, bringing illness and war, and devouring humans. To carry out both types of actions they descended from the sky, sometimes on ropes made of spiders’ webs (Torquemada Reference Torquemada1975–1983:vol. 3, bk. VI, p. 124). In the case of Quetzalcoatl, we see him descending—headfirst or walking on a rope—in the cosmogonies depicted in the Codex Vienna and probably also in the Codex Borgia (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Jiménez1992a:Plate 48, Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993b:Plate 32), while in the Codex Vaticanus A he is shown diving down to drive the world to its ruin (Anders and Jansen Reference Anders and Jansen1996b:f. 6r; Díaz Reference Díaz and Díaz2016:88–90).

Returning to the sculpture in the Friedenstein Palace's collections, the definition of the ambivalent Tzitzimime and Quetzalcoatl belonging to this group lead us to formulate a second complementary hypothesis regarding the figure represented on the forehead. Its descending position and iconography, blending Earth and Death gods’ attributes, suggest it might refer to the birth of the Wind God and his emergence in the world as well as to his Tzitzimitl nature and his cosmogonical actions and destructive behaviors. This explanation is supported by the small figure's claws and fleshless mouth, which are features of creation gods—the latter, for example, is a trait of the Mixtec primordial couple and parents of 9-Wind (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Jiménez1992a:Plate 51; Furst Reference Furst and Boone1982; Nicholson Reference Nicholson1978:66)—while they are also typical of menacing divinities who harm humans. This second hypothesis might explain why the small forehead figure seems to merge the traits of two protagonists seen in the central section of the Borgia: he combines the descending position of the deities, Quetzalcoatl in particular, moving through different levels of the cosmos—evoked by cut bodies—with a hooked nose, perhaps an attribute of Tzitzimime divinities. In fact, some scholars have identified the frame goddess with a hooked nose in Borgia 29 and the strip goddess from which Quetzalcoatl is born in Borgia 32 as Cihuacoatl (Figures 13c, 14a, and 14b), a deity whose iconographic traits and ambivalence match the Tzitzimime's appearance and nature (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993a:177–180, 192–243; Jansen and Pérez Jiménez Reference Jansen and Jiménez2017:450–458; Klein Reference Klein2000; Milbrath Reference Milbrath and Miller1988:161–163; Nowotny Reference Nowotny1977). Similarly, the skeletal entity that gives rise to multiple wind-related beings and ropes with descending spiders in Borgia 29 (Figure 14a) shares a cluster of attributes—stellar eye, fleshless mandible, face paint, series of flags in the background, not to mention a coiled-nose!—with a deity in plate 13 of the Codex Cospi, while both the appearance of these entities and their paraphernalia are reminiscent of the representation of a Tzitzimitl in the Codex Magliabechiano (Anders Reference Anders1970:f. 76r)—although in this latter image, painted during the Colonial era, the coiled or hooked nose is not present.

Last but not least, our interpretation is reinforced by the pair of volutes—one dark green and the other bright blue-green—that stand for the torso of the small forehead figure, as well as the additional volute below its teeth (Figure 10). As said, volutes could symbolize the wind's spiral gusts and were a distinctive feature of Wind Gods in Mesoamerica, as exemplified in the Gotha Bird Head, where we can see two volutes curled on top of the eyes to form the eyebrows and another one on top of the protuberance/nose to suggest the breath escaping from this appendage. In our view, the decision to render the descending figure's torso as volutes might have enhanced its characterization as a wind entity, while emphasizing this figure's connection to the Wind God manifestation represented in the Gotha sculpture. Additionally, depicting a volute near the descending figure's mouth might refer to the cosmogonical or destructive gusts blown by the Tzitzimitl Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl, a god that created the world by blowing and then ruined it with his winds (Dupey García Reference Dupey García2018b). The diminutive figure on the Gotha sculpture as a reference to the Tzitzimitl nature of the Wind God—perhaps manifested at his birth—is reinforced by its location on the forehead, a functional locus especially appropriate for expressing key aspects of the god's self or identity.

Original Appearance and Function of the Object

The flat wooden bar with a central knob on the top of the Bird Head lacks any trace of decoration except for a few tesserae on its front edge, suggesting this was originally the only visible part of it (Figures 5 and 7d). This leads us to believe the bar might have supported some kind of decoration, possibly a headdress, while the two holes on the sides of the head might have been used to tie this additional decorative item to ensure its stability (Figures 5 and 9a). But what kind of decorative attachment might be expected on the Gotha sculpture? Based on the iconography of the Nahua and Mixtec Wind Gods, their typical troncoconical headdresses come to mind (Figures 12b–12d), although it is difficult to imagine how a three-dimensional item could have stood on top of the narrow wooden bar. A perhaps more plausible idea is that the sculpture displayed a feathered head ornament. It could have had the shape and colors of Quetzalcoatl Ehecatl's fan-shaped ornament fashioned with dark and red feathers and spotted with stellar eyes, which sometimes was not fixed on the neck but on the upper back part of the god's head or, in other instances, was double and appeared on both the back and top of the head (Figure 12f; Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and García1991:Plates 3, 26, 27, Reference Anders, Jansen and García1993c:Plate 87). If so, the juxtaposition of precious stones, shells, and feathers would have further enhanced the multimedia character of the sculpture through three categories of materials whose different qualities of brilliance were highly prized in Postclassic central Mexican aesthetics (Caplan Reference Caplan2014, Reference Caplan2019; Dupey García Reference Dupey García, García and de Ágredos Pascual2018a; Russo Reference Russo, Wolf and Connors2011).

Our hypothesis is supported by references to mosaic-encrusted items decorated with feathers in diverse colonial inventories and chronicles. The Annals of Cuauhtitlan, in particular, relate the myth of the decadence of Tollan, in which Coyotlinahual, the patron deity of feather workers, fashioned a polychrome mosaic mask for king Quetzalcoatl; it had serpent teeth and was associated with a head fan (apanecayotl) and a beard made of feathers (Bierhorst Reference Bierhorst1992:30–33; Bassett Reference Bassett2015:30). Similarly, the attire of Quetzalcoatl sent to Hernán Cortés by Moctezuma II included, according to the Florentine Codex, a turquoise-mosaic mask “inserted on a high and big crown full of rich feathers, long and very beautiful, so that on placing the crown on the head, the mask was placed over the face” (engerida en una corona alta y grande, llena de plumas ricas, largas y muy hermosa, de manera que poniéndose la corona sobre la cabeza se ponía la mascara en la cara; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Austin and Quitana2000:vol. 3, p. 1167; English translation from Saville [Reference Saville1922:13–14]). A comparable association between a mosaic mask and a feathered item appears in the Tlaloc costume given on the same occasion, which included “a mask with its feather-work” (una máscara con su plumaje; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Austin and Quitana2000:vol. 3, p. 1168; English translation from Saville [Reference Saville1922:15]). It is also worth citing the list of objects that Cortés shipped to Spain together with his famous second letter, in which “two colored feather adornments that were for two gemstones helmets” (dos plumajes de colores que son para dos capacetes de pedrería) are mentioned (Cortés Reference Cortés1985:25). This last description inevitably recalls the mosaic-encrusted horned helmet today in the British Museum, which has a hole on top where feathers could have been inserted (McEwan et al. Reference McEwan, Colin, Cartwright and Stacey2006:53).