Book contents

- Texts and Violence in the Roman World

- Texts and Violence in the Roman World

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Comic Violence and the Citizen Body

- Chapter 2 Contemplating Violence

- Chapter 3 Discipline and Punish

- Chapter 4 Make War Not Love

- Chapter 5 Violence and Resistance in Ovid’s Metamorphoses

- Chapter 6 Tales of the Unexpurgated (Cert PG)

- Chapter 7 Dismemberment and the Critics

- Chapter 8 Violence and Alienation in Lucan’s Pharsalia

- Chapter 9 Tacitus and the Language of Violence

- Chapter 10 Cruel Narrative

- Chapter 11 Violence and the Christian Heroine

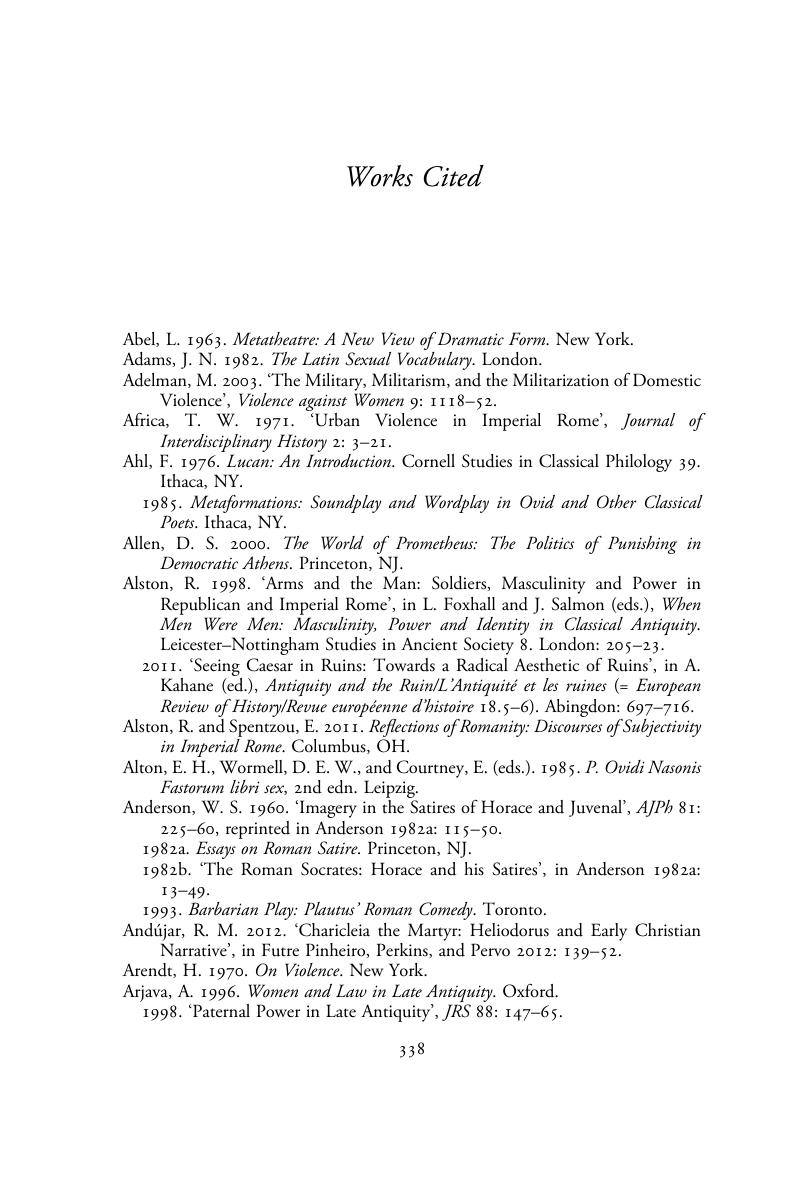

- Works Cited

- Index

- References

Works Cited

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 March 2018

- Texts and Violence in the Roman World

- Texts and Violence in the Roman World

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Comic Violence and the Citizen Body

- Chapter 2 Contemplating Violence

- Chapter 3 Discipline and Punish

- Chapter 4 Make War Not Love

- Chapter 5 Violence and Resistance in Ovid’s Metamorphoses

- Chapter 6 Tales of the Unexpurgated (Cert PG)

- Chapter 7 Dismemberment and the Critics

- Chapter 8 Violence and Alienation in Lucan’s Pharsalia

- Chapter 9 Tacitus and the Language of Violence

- Chapter 10 Cruel Narrative

- Chapter 11 Violence and the Christian Heroine

- Works Cited

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Texts and Violence in the Roman World , pp. 338 - 373Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2018