Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Map

- Foreword

- PART 1 Introduction: Africa is Seldom What It Seems

- Chapter 1 White South Africa and the South Africanisation of Science: Humankind or Kinds of Humans?

- PART 2 Introduction: Fossils and Genes: A New Anthropology of Evolution

- PART 3 Introduction: The Emerging Stone Age

- PART 4 Introduction: The Myth of the Vacant Land

- PART 5 Introduction: The Racial Paradox: Sterkfontein, Smuts and Segregation

- Epilogue: Voice of Politics, Voice of Science: Politics and Science After 1945

- Notes, references and recommended reading

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Index

Chapter 1 - White South Africa and the South Africanisation of Science: Humankind or Kinds of Humans?

from PART 1 - Introduction: Africa is Seldom What It Seems

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 31 May 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Map

- Foreword

- PART 1 Introduction: Africa is Seldom What It Seems

- Chapter 1 White South Africa and the South Africanisation of Science: Humankind or Kinds of Humans?

- PART 2 Introduction: Fossils and Genes: A New Anthropology of Evolution

- PART 3 Introduction: The Emerging Stone Age

- PART 4 Introduction: The Myth of the Vacant Land

- PART 5 Introduction: The Racial Paradox: Sterkfontein, Smuts and Segregation

- Epilogue: Voice of Politics, Voice of Science: Politics and Science After 1945

- Notes, references and recommended reading

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Index

Summary

The opening address to a conference on the ‘African Renais-Science’, held in Durban in 2002, was delivered by the world-renowned anatomist Phillip Tobias, who spoke on ‘Africa: The Cradle of Humanity’. In a brief survey of hominid development and human evolution, Tobias lent his personal authority to what is rapidly becoming part of a key set of tropes in the discourse of the African Renaissance: that Australopithecus africanus is the progenitor of all living humans; that ‘Africa gave the world its first culture’; and that hominids in southern Africa were ‘not a southern African aberration, but a pan-African revelation’ (Tobias 2002: 6, 10).

It is not without irony that one of the central tenets of the new African Renaissance amounts to a neat inversion of what was once a core component of the country's tradition of scientific racism and white South Africanist assertion (Dubow 1995). In segregationist South Africa the discovery of australopithecines and other fossil remains was commonly held up as proof of underlying typological racial difference in modern human beings: it emphasised evolutionary diversity over unity, and it proclaimed scientists like Raymond Dart and Robert Broom as exemplars of colonial South African scientific achievement.

Until quite recently, insistence on a linked evolutionary past did not necessarily imply a belief in a common humanity: humankind, it was widely assumed, was composed of different kinds of humans. Paradoxically, Dart's revelation that the African continent harboured the origins of humankind is now actively seguing into a romantic vision of indigenous initiative and achievement. The ‘back to Africa’ model which portrays the African continent as the original cradle of civilisation serves, in the words of Dialo Diop, as a key prop of ‘the cultural foundation of the African renaissance’. UNESCO's proclamation of the fossil-bearing sites at Sterkfontein as a World Heritage Site in 1999 has given an international seal of approval to a narrative that is also being marketed as the basis of ‘Afrikatourism’ (Diop 1999: 3–4, 8; see also Moaholi 1999).

Jan Smuts and the ‘Great Divide’

It is well to remember that to proclaim a linked evolutionary past is quite different from asserting a universal sense of humankind.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

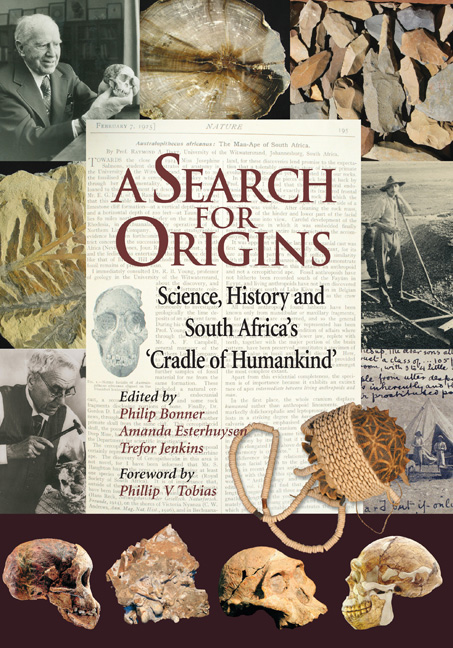

- A Search for OriginsScience, History and South Africa's ‘Cradle of Humankind’, pp. 9 - 22Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2007