The importance in Roman society of the family, and especially of an extensive family line, has long been taken for granted. It is the pattern that dominates literary texts concerned with the social elite as well as legal sources. During the Republic, the family group that mattered most was the gens, an extended clan whose members all descended in the male line from a common ancestor – which is what we call the ‘agnatic family’.Footnote 1 Later, so it is assumed, the agnatic family became less important while cognate family relations – that is, relations that also include kin in the female line – became more relevant.Footnote 2 In 1983, Keith Hopkins challenged this model fundamentally, and argued:

it looks as though, in the period from which such evidence survives (i.e. after about 200 BC), the Roman and Italian family was a small, short-lived social unit. It also seems as though broader kinship units, such as clans or clan segments (gentes), at least from this period onwards, played an unimportant role in burials.Footnote 3

While Hopkins’ conclusions were primarily based on insufficient awareness of the evidence, a year later Richard Saller and Brent Shaw reached similar conclusions through a statistical approach to 12,000–13,000 tomb stones from various parts of the Roman empire. They counted each attested type of relationship between commemorator and commemorated, and then classified and added them up as either nuclear family (i.e. parents with their children) or extended relationships.Footnote 4 For the city of Rome, this resulted in 72 per cent nuclear relationships in the senatorial class, 77 per cent in the first two orders combined and 78 per cent in the lower classes.Footnote 5 Independently of Hopkins, but explicitly endorsing views previously expressed by De Visscher, they concluded that ‘Most tombs of the imperial period were de facto personal tombs and were not tied to any strong conception or practice of maintaining long agnatic family lineages.’Footnote 6

Their approach was challenged in 1996 by Dale Martin, who argued that counting individual relationships would not adequately represent family burials.Footnote 7 While, in Saller and Shaw’s counting, a dedication by a man to his wife, his children, his brother and his parents would result in four nuclear relationships, the actual inscription commemorated three generations, thus representing what in their terms is an extended family. The dedication by a man to his wife, child, brother and amicus would result in three nuclear relationships and one extended, while assessing the epitaph as a whole would again result in the commemoration of one extended group of relations. Drawing on 1,161 epitaphs from seven different places in Asia Minor, and classifying entire inscriptions, Martin arrived at markedly different numbers from those of Saller and Shaw, even though figures for individual places differed considerably. Yet he still maintained that, while not strictly nuclear, the family groups he found were normally small and clustered around a nuclear family unit.Footnote 8

Martin in particular has taken his observations to reflect not only funerary customs, but family structures as such. While Saller and Shaw were more cautious in this regard, they still suggested that funerary customs reflected Roman familial relations more generally, which were dominated by the nuclear family of a married couple and their children as opposed to the extended family. The Roman family thus became an early predecessor of our modern circumstances.Footnote 9 Such far-reaching conclusions have been duly criticised,Footnote 10 and Sabine Huebner has demonstrated for Egypt that the 86.9 per cent of epitaphs representing nuclear family commemorations present a stark contrast to domestic cohabitation practices as documented in census registers.Footnote 11 It is therefore worth keeping in mind that evidence from epitaphs informs us first and foremost about commemorative practices, and the greatest of caution is needed when drawing more general conclusions about family relationships and compositions.Footnote 12 Today, far more flexible models of what a family may have been are prevalent. They allow for the possibility that familial relations may be conceptualised differently in different contexts, for instance in (inheritance) law; in the composition of domestic units; in informal, ideologically determined relationships of obligation; or in personal affection, all potentially varying again depending on social class and economic means. They take account of changes in individual household composition and size over time, resulting from death, marriage, remarriage, childbirth, adoption and so on, and of the fact that the household may be both larger and smaller than a ‘family’ (depending on its definition) as it can include unrelated servants without comprising all kin.Footnote 13

For research on the funerary sphere, however, Saller and Shaw’s conclusions are still hugely influential, not least since they coincide with what legal historians have always thought could be extracted from law codes and epigraphy.Footnote 14 The vast number of inscriptions and tombs preserved, and the very limited attention paid to the later history of tombs by excavators and historians alike, further encourages the general view that, during the imperial period, long family lines were irrelevant in the funerary realm, and any Roman man (and many women as well) who could afford to build a tomb would do so.Footnote 15 Moreover, there is a prevailing assumption among certain scholars that Roman society of the imperial period was on the road to ever-increasing individualism at the cost of both societal and family coherence.Footnote 16

However, there is little actual evidence to support these views. Through a careful analysis of individual tomb contexts, this chapter aims to demonstrate how problematic are both the conclusions and the methodologies by which they were arrived at. In a first step, I take a look at the senatorial class, who proudly presented their family history in their tombs, and sometimes referred to it in their epitaphs, well into late antiquity. I shall then turn to the lower classes and argue that they too shared the ideals of the senatorial elite, but expressed and adapted them in a class-specific manner that differed in key aspects from senatorial habits.

Elite Burials

It is generally acknowledged that at least some of the great families of the Republic erected mausolea that were used over several generations. Most of the evidence comes from literary texts, and it has become customary to quote Cicero’s list of examples outside Porta Capena (Tusc. 1.7.13). Only one of these mausolea has been identified in the archaeological record, the tomb of the Scipios.

The Tomb of the Scipios

The tomb was founded as a family tomb of the patrician Cornelii Scipiones, either by L. Cornelius Scipio Barbatus (cos. 298 BCE) himself or by his sons, and around 280 BCE Barbatus was the first to be buried within it in his unique and famous sarcophagus (Figures 3.1 and 3.2).Footnote 17 Around 150, the main burial chamber probably contained some thirty-three sarcophagi and was filled to capacity, so that a second chamber was cut into the adjacent rock. At the same time, and above a frieze that had long displayed frescoes of military deeds and other political matters in which the family was involved,Footnote 18 the rock face received a showy façade containing three statues (Figure 3.3): of Scipio Africanus, the famous victor over Hannibal; of his brother Scipio Asiagenus (Asiaticus), the victor over Antiochos III of Syria; and of Ennius, who had immortalised the family and its history in his poetry.Footnote 19 The tomb probably continued to be used into the early first century BCE, and may have fallen out of use after the last descendant of the Cornelii Scipiones had died.

Figure 3.1 Tomb of the Scipios off the via Appia, updated plan by Lucia Domenica Simeone and Roberta Loreti

Figure 3.2 Sarcophagus of L. Cornelius Scipio Barbatus, around 280 BCE, copy in situ of the original casket

Figure 3.3 Reconstruction of the façade of the tomb of the Scipios based on recent research by the Sovrintendenza ai Beni Culturali di Roma Capitale

Unfortunately, only eight inscriptions pertaining to these burials have survived and not all the individuals can be identified with certainty. Still, those that feature inscriptions allow for some further conclusions (cf. Stemma 1). According to the epitaphs, the tomb contained the remains of Scipio Barbatus; his son L. Cornelius Scipio (cos. 259 BCE); a grandson of Scipio Africanus; the son and grandson of Scipio Asiagenus; as well as the sons and wife of Scipio Hispallus (cos. 176 BCE). Since both his sons and his wife were buried in the tomb, it is almost certain that Hispallus himself was also put to rest there.

Stemma 1 Stemma of the Cornelii Scipiones and Cornelii Lentuli. Bold: individuals buried in the family tomb according to epigraphic evidence; regular: individuals likely buried in the family tomb; italics: individuals potentially buried in the family tomb or buried elsewhere; ††: violent death

Whether the same is true for Scipio Africanus, who was commemorated in one of the statues, is debated. After his political enemies had accused him of corruption, he had retreated to his villa in Liternum in Campania. It is clear from Livy (38.56.1–4), Seneca (Ep. 86.1) and other sourcesFootnote 20 that some thought he had died and been buried there, but both Livy and Seneca acknowledge that the veracity of this tradition is far from certain.Footnote 21 Be that as it may, even if Africanus was buried in his villa, it would have been a singular and individual decision, and not the end of the family mausoleum or a sign of his family branch opting out of it. Nothing is known about the time or place of Asiagenus’ burial, but since his statue equally decorated the façade and, more importantly, since his son and at least one grandson were buried in the family mausoleum, it is highly likely that the same applies to him.

Two aspects of the epitaphs found in the mausoleum are particularly interesting to note. First, up to this time only agnate relatives were buried in the mausoleum; that is, family in the male line.Footnote 22 Secondly, this is true not just for one single strand of the family, but for members of different family lines, stirpes, which is particularly remarkable since some family members (Africanus and Asiagenus) had offspring and were sufficiently prominent that they could have established separate stirpes, with their own tombs – just as Barbatus had done. The tomb therefore reflects the idea of the family clan, which consists of all male family lines descended from a common ancestor.Footnote 23

It is possible, and generally assumed, that the tomb went out of use for some time after the last agnate descendants of Barbatus had died in the first century BCE. However, three epitaphs for members of the Cornelii Lentuli, and two niches for cinerary urns cut into the rock, attest to further burials during the first century CE.Footnote 24 The Cornelii Lentuli must therefore have inherited the family tomb in the cognate line after the extinction of the Scipios, probably through a daughter of P. Cornelius Scipio Nascia Serapio (cos. 111 BCE), who married P. Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus (monetalis in 101 BCE) (Stemma 1). The details of stemmata through the first centuries BCE and CE are debated,Footnote 25 and it is unclear how many first-century CE burials we should expect to have occurred. While only three inscriptions have been recorded, with the change to marble containers and tabulae a material was chosen that was far more prone to being carried away and repurposed or burnt to produce lime.Footnote 26 Nevertheless, some speculation may be permitted. The earliest epitaph commemorates Ser. Lentulus Maluginensis,Footnote 27 who is most likely the consul suffectus of 10 CE.Footnote 28 The latest epitaph commemorates M. Iunius Silanus Lutatius Catulus,Footnote 29 who boasts in his epitaph of being the great-grandson of Cossus (Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus, cos. 1 BCE), grandson of Gaetulicus (probably Cn. Lentulus Gaetulicus, cos. 26 CE) and son of D. Silanus.Footnote 30 Some members of the Lentuli therefore used the tomb over at least four generations. Moreover, Cossus and Maluginensis, as well as P. Cornelius Lentulus Scipio (consul suffectus 2 CE), were most likely brothers, whose father took their cognomina from famous but by then extinct branches of the Cornelii.Footnote 31 The strong sense of family tradition displayed in this choice certainly fits very well with the family’s reopening of the Scipios’ tomb.

The Plautii Tumulus

The mausoleum of the patrician Plautii was an impressive tower-like tumulus just across the Ponte Lucano near Tibur (Figure 3.4). Its titulus high up on the tambour commemorates the founder of the tomb, M. Plautius Silvanus, consul in 2 BCE with Augustus, and his wife. The street front of the tomb’s rectangular base featured further inscriptions on panels framed by Corinthian half-columns, three of which have been recorded (cf. Stemma 2).Footnote 32 In the centre we find Silvanus and his wife, as well as their son A. Plautius Urgulanius, who died at the age of nine. Another son of Silvanus, P. Plautius Pulcher, who was elevated to patrician status but died before his consulship in the early 50s, was commemorated together with his wife in the right-hand aedicula. Finally, the left-hand aedicula honoured Ti. Plautius Silvanus Aelianus, who died shortly after his second consulship in 74 (and before 79).Footnote 33 After the tomb had been in use over four generations by the agnate family of its founder, the last descendant of the family seems to have been L. Aelius Lamia Plautius Aelianus, the consul of 80,Footnote 34 and it was closed after the family name became extinct.Footnote 35

Figure 3.4 Tumulus of the Plautii (first century CE) drawn by Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Stemma 2 Stemma of the Plautii. Bold: individuals buried in the family tomb according to epigraphic evidence; regular: individuals likely buried in the family tomb; italics: individuals potentially buried in the family tomb or buried elsewhere

Tomb of the Licinii and Calpurnii

The tomb of the Licinii just outside Porta Collina between via Salaria and via Nomentana is the other most frequently mentioned example of a family tomb used over several generations, although it has long been regarded with equal measures of amazement and suspicion. The excavations were poorly documented, and many of the objects found were exported illegally with the inglorious help of Wolfgang Helbig. Margherita Guarducci cast serious and general doubts on Helbig’s reliability as a source, and consequently it has often been questioned whether all the objects Helbig mentioned actually did come from a single tomb.Footnote 36 However, in 1986 Dietrich Boschung put forward strong arguments against Guarducci’s concerns, and in favour of a common provenance from the Licinian tomb of thirteen portraits now in Copenhagen.Footnote 37 In 2003, Frances Van Keuren published new archival material that clarified matters further, demonstrating not least that Lanciani, who published a plan of the tomb complex in his Forma Urbis Romae (Figure 3.5), visited the tomb on various occasions.Footnote 38 His plan cannot therefore be dismissed as mere fantasy, but rather confirms Helbig’s claim that the three ‘chambers’ eventually excavated all formed one building complex.Footnote 39 We can thus be fairly confident in studying the evidence taken together as attesting to a tomb of one of the most powerful Roman families that was in use for over 150 years.

Figure 3.5 Plan of the tomb of the Licinii and Calpurnii on via Salaria as recorded by Rodolfo Lanciani in his Forma Urbis Romae, location and close-up

Originally, the tomb was a very small building of just 1.5 x 3.6 m, perhaps containing some of the inscribed altars (Figure 3.6) and featuring aediculae containing cinerary urns and possibly also portraits.Footnote 40 The first generation to use the tomb that is attested by inscribed altars is that of M. Licinius Crassus Frugi pontifex and his wife, and it is likely that they were its founders (cf. Stemma 3).Footnote 41 Licinius Crassus Frugi and his family were among the most powerful actors on the political stage during the first century CE, related not only to prominent figures of the Republic, but also to several imperial dynasties. Yet precisely for this reason they posed a threat to the emperors, and none of the more prominent (and some less prominent) family members died of natural causes.Footnote 42 The consul himself, his wife Scribonia and their son Cn. Pompeius Magnus were killed, probably in 47, on the order of Claudius (possibly on the initiative of Messalina), who also was Pompeius’ father-in-law.Footnote 43 Another son, M. Licinius Crassus Frugi, consul in 64, was executed for treason in 67, while yet another, L. Calpurnius Piso Frugi Licinianus, had been adopted by the short-lived emperor Galba, but was murdered together with his wife after the emperor’s downfall in 69, the same year that the fourth brother, Scribonianus, also fell victim to the power struggles.Footnote 44 Further family members buried in the tomb probably include the founder’s daughter Licinia Magna, certainly her sister Licinia, who probably died as a child, and Calpurnia Lepida, probably a granddaughter of Frugi pontifex.Footnote 45 Later, Crassus Frugi’s grandson C. Calpurnius Crassus Frugi Licinianus, consul in 87, plotted against Nerva, and was first exiled and later killed in 117, shortly after Hadrian’s accession. He or his homonymous son, who died at a young age, must have been the last male member of this branch of the family.Footnote 46

Figure 3.6 Four altars from the Licinian tomb, Rome, Museo Nazionale delle Terme inv. 78163 (Cn. Pompeius Magnus), 78163 (L. Calpurnius Piso Frugi Licinianus and his wife Verania Gemina), 78161 (Calpurnia Lepida Orfiti), 78167 (Licinia Cornelia Volusia Torquata)

Stemma 3 Stemma of the Licinii and Calpurnii. Bold: individuals buried in the family tomb according to epigraphic evidence; regular: individuals likely buried in the family tomb; italics: individuals potentially buried in the family tomb or buried elsewhere; ††: violent death

A strong sense of family and pride in its ancestry was expressed and advertised through the famous portraits originating from the tomb, which comprised both statues and busts or herms.Footnote 47 Statues in front of the small mausoleum honoured Licinius Crassus Frugi and his wife as well as a woman of a previous generation, tentatively identified by Van Keuren as Scribonia’s mother (Figure 3.7).Footnote 48 Two portraits of female relatives of roughly the same generation as Scribonia may equally have belonged to statues.Footnote 49 The same goes for a highly expressive head of a youth that is usually identified as Pompeius Magnus, who was killed with his parents.Footnote 50 However, given that this portrait is later than the others,Footnote 51 and that Pompeius was well over twenty when he died – after all, he had held the office of quaestor and been given the honour of announcing in Rome Claudius’ victory over Britain on his return – it is highly unlikely that his commemorative portrait would have depicted him with the features of a boy.Footnote 52 The head must show an anonymous son or, more likely, grandson of Crassus Frugi pontifex.

Figure 3.7 Heads of the portrait statues, herm portraits and busts from the Licinian tomb: a) IN 749 (Crassus triumvir); b) IN 733 (Pompey the Great); c) IN 736; d) IN 738; e) IN 737; f) IN 741; g) IN 734 (Frugi pontifex?); h) IN 751 (Scribonia?); i) IN 747; j) IN 754; k) IN 735

All other portraits associated with the tomb depict ancestors. Their exact number and composition are debated, but a core of four items can be attributed with some certainty based on the documentary evidence mentioned above. The triumvir Pompey the Great, an ancestor of Scribonia who also lent his name to the couple’s son, featured prominently. Whether his head belonged to a bust – the format chosen for the other Republican ancestors – or to a statue is not clear but the latter should not be ruled out, especially since it is the largest head among the group.Footnote 53 The other three portraits, this time busts that were on display either in aediculae inside the tomb or set into herm shafts belong to women and display hairstyles from the 30s BCE, and thus must equally show ancestors (Figure 3.7). As Boschung observed, the age and the fashion of the elderly woman, as well as her family resemblance to Pompey the Great, may suggest that she is his daughter Pompeia, who was the ancestor establishing Scribonia’s relation with the triumvir.Footnote 54 The two young women, so like each other that they could be sisters but quite different in technical execution, cannot be identified.Footnote 55 To these Republican ancestral portraits must probably be added a bust of M. Licinius Crassus triumvir, ancestor of Licinius Crassus Frugi.Footnote 56

It is not necessary for our purposes to discuss in any detail the other portraits potentially belonging to the tomb, as the picture is already clear enough.Footnote 57 An enthusiastic Helbig wrote in 1887: ‘I drew the conclusion that the cella in a certain sense had represented a tablinium adorned with ancestral portraits which, however, were made of marble rather than wax.’Footnote 58 His excitement was certainly justified. Despite all our dissatisfaction with the documentation of this aristocratic tomb, it gives us a rare glimpse into the ways in which elite families used the funerary realm for the display of their ancestry, which, in turn, was a major factor in the establishment of their power.Footnote 59 As Tacitus notes, Scribonia’s uncle dwelled ‘ostentatiously on his great-grandfather Pompeius, his aunt Scribonia, who had formerly been wife of Augustus, his imperial cousins, his house crowded with ancestral busts’ in order to challenge imperial power (Tacitus, Ann. 2.27, transl. A. J. Church), and these types of argument were not uncommon (cf. Tacitus, Ann. 3.76).Footnote 60 What is remarkable about our tomb is the predominance of women’s portraits, while the tomb itself was clearly used and handed down in the agnatic line as long as it continued. It is possible that some male portraits have fallen victim to damnatio memoriae,Footnote 61 or that the family was prevented from displaying the portraits of some of those who were condemned to death.Footnote 62 Yet the display of these women, independently of their original numerical proportion, is certainly also an acknowledgement of their role in establishing the family ties with the famous triumviri, and has parallels in the genealogical praise of women in funerary orations, and women’s role as ancestors more widely.Footnote 63

In any case, the story of the tomb does not end with the termination of the agnate descendants of Crassus Frugi. When the male line became extinct, a branch of the Calpurnii that was related by the female line, probably through the daughter of Crassus Frugi, Licinia Magna, must have inherited the mausoleum and used it throughout the second century (Stemma 3).Footnote 64 This is suggested by a number of observations. First, an extension to the tomb was built in the Antonine period, as Lanciani’s drawing (Figure 3.5) and brick stamps attest.Footnote 65 Secondly, at least ten sarcophagi were found in the tomb that commence around the time when the altars leave off (see earlier Figures 1.28–1.30). Thirdly, an alabaster bust of Licinia Procula, a close relative of L. Calpurnius Proculus Piso, consul in 175, was found close by and potentially comes from our tomb; and finally, a number of epitaphs from the area attest to the burial of freedmen of the Calpurnii in the vicinity.Footnote 66

No inscriptions for other Calpurnii are preserved, but the sarcophagi from the tomb can be dated fairly well and attributed to adults and children according to their size. They appear to belong to three or four distinct groups, each representing a generation of the family.Footnote 67 In the so-called second chamber, a huge plain sarcophagus appears to be the earliest piece.Footnote 68 It was carefully divided into two separate compartments by a marble panel fixed in grooves on the small sides, and cushion-like headrests supported the deceased. It was probably set up by and for the first Calpurnius family head and his wife. Two sarcophagi of smaller size appear to have belonged to their children (Figure 1.28a–b):Footnote 69 a garland sarcophagus from about 130Footnote 70 and a griffon sarcophagus from c. 130–40.Footnote 71 Whether a garland sarcophagus imported from Asia Minor c. 140–50 (Figure 1.28c) contained another of their children or a grandchild (or the child of another relative) is not entirely clear from its date.Footnote 72 Equally, the next full-size sarcophagus from around 150, showing a Dionysiac thiasos (Figure 1.29a),Footnote 73 may represent an adult son or, less likely, a daughter or first wife of paterfamilias no. 2. The next, more monumental sarcophagus with the Rape of the Leucippidae and Victories sacrificing bulls on the lid, was again extra wide for a double burial, and has a terminus post quem indicated by a coin of Antoninus Pius found within but may date around 170 (Figure 1.29b).Footnote 74 A child’s sarcophagus depicting the childhood of Dionysus from around 160,Footnote 75 and a child’s Cupid Race sarcophagus dated only roughly to 150–75, are likely to be associated with the patrons of this sarcophagus (Figures 1.29c–d).Footnote 76

The final three sarcophagi were found in a third chamber that may never have been fully excavated (Figure 1.30).Footnote 77 They are the most imposing pieces from the tomb for both their size and their quality of craftsmanship. Their date is disputed, except for the Ariadne casket from the first decade of the third century.Footnote 78 The sarcophagus showing the Indian Triumph of Dionysus is clearly older, probably dating to the late 170s or 180s, while the Victory sarcophagus with its muscular and still rather stocky putti seems to belong somewhere in between the others.Footnote 79

Without inscriptions, any detailed attribution of these sarcophagi must remain speculative, but it may be worth testing whether a plausible scenario can be suggested at all. Henning Wrede has tentatively and convincingly attributed the Dionysiac Victory sarcophagus from the final group to either Ser. Calpurnius Piso Orfitus (cos. 172), who died after 191, or to his brother L. Calpurnius Proculus Piso (cos. 175), who died after 204.Footnote 80 It is equally tempting to attribute the other casket from the third group with its ostentatious display of victory motifs, which contained one skeleton with some residues that could hint at an attempt at embalming of the corpse, to the other brother. The Ariadne sarcophagus may then have served either a wife of one of the consuls or a daughter or sister of either brother as a final resting place.Footnote 81 The family tree of this branch of the Calpurnii is partly conjectural (Stemma 3). Yet, assuming that the generally accepted prosopography is correct,Footnote 82 the plain double sarcophagus that started the series could have belonged to C. Calpurnius Piso, grandson of Licinia Magna and consul in 111, who could have inherited the tomb after the consul suffectus of 87 had been killed, shortly after Hadrian’s accession, leaving no (male) descendants.Footnote 83 The Leucippidae sarcophagus, equally wider than normal and thus designed for a couple, would have belonged to the father of Orfitus and Piso, who was perhaps Ser. (Calpurnius Piso/Scipio?) Orfitus, and his wife.Footnote 84

This remains mere speculation, but it demonstrates that the dates and types of sarcophagi are in tune with the family history as we know it. Here, it is most important that the evidence strongly suggests that, after it was taken over by another stirps of the Calpurnii, the tomb continued to be used by at least three consecutive generations of the agnate family, most likely including two adult brothers, and thus in a gentilicial fashion. They took pride in the long family history that went back even to the late Republic, a history that was right in front of their eyes through portraits, inscriptions and a multitude of containers for the remains of their ancestors.

The three family tombs discussed so far are clearly the best-documented senatorial mausolea at Rome, which also allow for the greatest detail of information over the longest period of usage. However, additional, more fragmentary evidence suggests that they were not exceptional at their time. In Tusculum, at least eight cinerary urns of the patrician Furii were found in the seventeenth century, all commemorating male members of the family by inscription.Footnote 85 A large tumulus in the horti of Agrippa in the Vatican area, first dedicated to Vipsania Agrippina, daughter of Agrippa, who married C. Asinius Gallus after a forced divorce from Tiberius, was used by the Asinii at least into the early second century.Footnote 86 An even longer period of usage may be attested by an epitaph for Q. Gallonius C. f. Fronto Q. Marcius Turbo and his son.Footnote 87 He has been identified as the governor of Thrace in 145–55, and may be either an adoptive son of Hadrian’s powerful praetorian prefect Q. Marcius Turbo Fronto Publicius Severus, or his biological son, who was later adopted by one Gallonius, which is far more likely.Footnote 88 The two fragments were found with other debris from monuments in one of the towers of the ancient Porta Flaminia. Yet, as the inscription fragments are curved and framed by a kyma that has close parallels in the Augustan period, it is possible that they belong to a tumulus monument of roughly that period.Footnote 89 It is thus possible that Q. Gallonius C. f. Fronto Q. Marcius Turbo’s inscription (also commemorating his son) was added to a family monument of the Gallonii that went back to the late Republic or Augustan period.Footnote 90 According to the Historia Augusta (Did. 8.10), the short-lived emperor Didius Iulianus was buried in the mausoleum of his great-grandfather at the fifth mile of the Labicana.Footnote 91 In other cases, at least the burials of father and adult son are attested for the same tomb.Footnote 92 A rare late third-century double epitaph commemorates two brothers in the same titulus, T. Flavius Postumius Quietus, consul in 272, and T. Flavius Postumius Titianus, consul c. 283–84 and 310, suggesting that both of their families used the tomb.Footnote 93

I have discussed elsewhere further senatorial tombs that are likely to have been used in a similar fashion all the way through to late antiquity. These include the tomb of the Acilii Glabriones, established in the late first or early second century on the via Salaria and used until the family left Rome at the beginning of the fourth century, when the entire area was handed over to the Church.Footnote 94 The tomb of the Sempronii not far from the mausoleum of the Scipios must have been founded at roughly the same time, and was then extended in one or two steps in a similar way to the Licinii tomb.Footnote 95 Some anonymous tombs may equally have belonged to senatorial families due to their prominence, location and treatment. The tower-like tumulus called the Sepolcro dei Servilii at the third mile of the Appia, founded towards the end of the first century BCE, shows signs of continued use until at least the early second century CE.Footnote 96 A tumulus 23 m in diameter at the eleventh mile of the same road was updated with a showy colonnade for sculpture display at the end of the second or beginning of the third century.Footnote 97 A splendid temple tomb attached to the so-called ‘Villa ad duas lauros’ on the via Latina, one of the largest and most impressive late antique villas in the Roman suburbium, was used, or at least maintained, from its foundation around 200 to the early fifth century (see Figure 1.11).Footnote 98

Admittedly, even including these examples, the sample of senatorial tombs used over several generations is limited. Nevertheless, what we have observed in these examples must actually have been common practice.Footnote 99 This is most clearly demonstrated by the main tituli of senatorial tombs.Footnote 100 The more than seventy examples from the vicinity of Rome that have preserved their patron’s name pertain almost exclusively to homines novi; that is, to social climbers who had only recently been promoted to senatorial status, and who often moved to Rome on that occasion.Footnote 101 It follows that their descendants as well as members of the old families are highly likely to have been buried in the tombs of their forefathers, albeit mostly without leaving any epigraphical trace. Apparently, only those who first achieved a family’s promotion to the highest status group founded tombs.

The evidence, lacunose as it may be, leaves little room for doubt about the great importance not only of the extended family with a long tradition, but of the use of family mausolea for showcasing the fact. Senatorial mausolea were often used over several generations and were preferably bequeathed in the agnatic line. After the extinction of the family line, the tomb may have been closed forever, or else inherited by a cognate branch of the family in the female line.

This result also demonstrates an important methodological point. When we only look at individual epitaphs – say, a single titulus or inscribed altar – we get the statistical pattern that Saller and Shaw produced for the senatorial class more generally. Where a commemorator is mentioned at all, it is normally a close relative. This pattern largely remains the same whether we count individual relationships, as they did, or inscriptions as proposed by Martin, although commemoration beyond the nuclear family becomes more apparent in the latter case.Footnote 102 Counting only tomb tituli, Saller and Shaw’s method results in 75 per cent nuclear family relations, 14 per cent extended family and 11 per cent non-kin relations, while the figures for Martin’s method are 70, 15 and 15 per cent, respectively.Footnote 103 It is notable, however, that over 54 per cent of tituli that are sufficiently well preserved to allow for a judgement are lacking a commemorator, and just over 36 and 11 per cent, respectively, commemorate a single man or woman.

While all these statistics are interesting in their own way, they obviously fail to account for the use of the tombs to which the tituli were affixed, and for the prominent role these monuments played in the promotion of the extended family. Each epitaph is only a snapshot of a moment in time, a single event in the long history of a tomb. This is true even for Hadrian’s mausoleum (see Figure 2.10): its main inscription declares its dedication by Antoninus Pius to Hadrian and Sabina even though it was founded as a dynastic tomb – and by Hadrian.Footnote 104 In some cases, later generations were commemorated in additional inscriptions on the outside of the tomb, as was again the case for the Mausoleum of Hadrian, but also for that of the Plautii, the Asinii and the third-century Postumii,Footnote 105 and probably for the Mussidii and Appii.Footnote 106 Given the lacunarity of our evidence, it is likely that additional tituli from other tombs have been lost. Yet it would also be wrong to draw conclusions about the use of a tomb from its façade tituli only. If we want to assess the role of tombs and commemorative practices in Roman senatorial families, we need to look at both the relationship between commemorator and deceased and that between these two parties and the entire user group of the mausoleum. The first is what Saller and Shaw have in fact examined. Theirs is an important result, as it tells us something about the hierarchy of obligations, pietas in Roman terms, but perhaps also about the closest emotional bonds within a family. The larger context, however, demonstrates very clearly the continuing importance of a long family line, and the key role that the family mausoleum played in promoting it after the use of imagines maiorum in the domestic atria had lost importance.Footnote 107

Sub-elite Tombs

The first element to note when we are considering non-elite Roman burials is that we are really mainly talking about the freedman milieu. As Lily Taylor and Henrik Mouritsen have argued, we know almost nothing about the burial customs of the freeborn non-elite population; they estimated that up to 90 per cent of all extant tomb tituli refer to freedmen and their first-generation descendants.Footnote 108 While this is an important and interesting observation in itself that merits further examination, it also constitutes one of the strongest arguments for the use of their tombs. As in the case of senators, the inescapable consequence is that the descendants of these freedmen normally continued to use their ancestral tomb. The only occasional exception are the first-generation descendants of freedmen, who had achieved a further social advancement since they were freeborn. We thus see the same principles at work as among the elite: only those who had considerably advanced their status founded a new tomb.

Much has been written about the significance of familyFootnote 109 as demonstrated on or in the tombs of freedmen of the first centuries BCE and CE.Footnote 110 Whoever could afford it, so it seems, decorated their tomb with relief portraits, which often depicted entire family groups, and prominently displayed their legal marriage by showing husband and wife clasping hands and by presenting freeborn children in a prominent place with their formal markers of status, the toga and bulla (Figure 3.8).Footnote 111 After all, these were major achievements attached to their new legal status, and freeborn children were expected to fulfil all the ambitions which their parents were barred from achieving by their servile birth. More recently, it has also been pointed out that a legal family had particular value beyond being a marker of status. These freedmen were also celebrating their escape from the precarity of the informal slave family,Footnote 112 which could be broken up any time by its owner or an heir, and whose members were prone to physical, including sexual, assaults.Footnote 113 These relief representations are discontinued after the Augustan period (although they experience a revival in lesser numbers in the second century) and it is hard to tell to what extent busts or statues took over their function in later tombs due to a lack of archaeological context in most cases. A rare exception is the lost Trajanic tomb of the Caltilii at Ostia, where the portraits of three generations were shown in pairs of shallow reliefs on the walls, and additions such as avia or mater clarify their relation to one another.Footnote 114 Yet I would argue that the tomb tituli as we find them in their thousands from tombs of the first to third centuries CE take over a similar function.

Figure 3.8 Tomb relief of the Servilii family, early Augustan; Rome, Musei Vaticani, Museo Gregoriano Profano 10491

Tituli

The reasons for the above statement may not seem obvious. The great legal historian Max Kaser in particular observed that tomb tituli often only name the founder of a tomb, and frequently a spouse, while children and the rest of the family are not always mentioned and, where they are, are often designated only as suis (‘his own’), liberi (‘free’) or posteri (‘descendants’). The explanations Kaser offered were ‘increasing childlessness and a waning sense of family’, as well as the tomb founder’s expectation that his children would build their own tombs.Footnote 115 Yet, in most cases, senatorial tituli equally only mention the tomb’s founder or the individual to whom the tomb was first dedicated (over 74 per cent), and rarely a spouse or child (9 per cent each).Footnote 116 From this point of view, it is remarkable that the freedmen mention their spouses and offspring at all,Footnote 117 and that the numbers are even the reverse. Over 64 per cent of all tituli from the ‘house’ and ‘terraced’ tombs in the Isola Sacra include at least one named child (c. 33 per cent) or unnamed offspring in general (c. 31 per cent), and the collective terms used could easily encompass later generations of descendants as well.

In some instances, the idea of founding a multigenerational family mausoleum modelled on aristocratic patterns is already clear from the titulus. A funerary altar from the early second century, for instance, was dedicated by L. Tossius Successus, who was lictor of the emperor and clearly familiar with elite ideology, to his wife, his parents and his three sons, thus establishing three generations already in the epitaph, and surely implicitly expressing the hope that his sons would carry on the name with their families.Footnote 118

Perhaps the most striking feature distinguishing senatorial from sub-elite tituli is that the latter frequently include freedmen among those with burial rights. This is typically done with the phrase libertis libertabusque posterisque eorum; that is, including not only male and female ex-slaves but even their descendants. In the Isola Sacra, 90 per cent of all ‘house’ tombs feature the phrase. To consider this addition only in legal terms, as is usually done, in fact misses the point, especially since the formula does not signify what it seems to say. It appears to admit to burial all freed slaves of a founder and all of their offspring, and it has often been taken to mean just that by modern scholars.Footnote 119 However, in reality only those libertini and their descendants were admitted who either were themselves heirs of the tomb or got permission from its founder while he was still alive, or from his heirs. This is confirmed by well-documented tombs as well as by the jurists, and first attested for Ulpian, a jurist of the early third century, who explains:

Freedmen can neither be buried nor bury others, unless they are heirs to their patron, although some people have inscribed on their tomb that they have built it for themselves and their freedmen: this view was given by Papinian [142–212 CE], and there has often been a ruling to this effect.Footnote 120

The formula was thus by no means a free-for-all, but neither was it necessary for protection of the rights of heirs to mention them in a titulus as long as a will attested to their admission. The formula’s main function must therefore be sought outside the legal realm. One effect was obviously to demonstrate another achievement of the tomb patrons’ new status. Only as (wealthy) citizens did they have the opportunity to acquire slaves of their own, and to set them free.Footnote 121 Moreover, as John Bodel observes, their care for a respectable final resting place for their dependants presents them as generous benefactors.Footnote 122 Stelae and other small tombs, which are occasionally dedicated to an entire household even when it must have been obvious from the start that there was not enough space for multiple burials over a long period of time, are best suited to demonstrate these points.Footnote 123 In addition, where the tomb was large enough to offer liberti burial space, they were also seen as an insurance for lasting commemoration of the tomb’s founder, especially when no natural descendants could fulfil this duty. As Detlef Liebs has shown, this is sometimes explicitly stated in epitaphs.Footnote 124

However, as with former slaves’ legal offspring, having a familia was not just a one-time achievement, nor was making them heirs only about commemoration of the tomb’s founder. The latter task could easily be performed by external heirs, or by liberti who were not admitted to burial, as is again demonstrated by epitaphs.Footnote 125 Since slaves, being ‘property’, had neither legal parents nor children, freedpeople lacked legal ancestors. Often they will have died without a legal son to become male heir, either because their natural children remained in the possession of their patrons, they died prematurely or the freed slaves’ age at manumission prevented them from producing sufficient numbers of surviving male offspring.Footnote 126 Both these deficits could be mitigated to some extent by drawing upon the familia.

Patrons as Pseudo-ancestors

Occasionally, we find patrons buried with and by their own former slaves. This is less striking a thing to do than one may think. We can probably assume that these patrons often belonged to a similar milieu as the freedpeople with whom they were buried. They will not already have built a tomb of their own, thus appreciating the opportunity of being offered one, especially one in which they received a place of honour and could hope for commemoration for a prolonged period of time. One may even wonder whether at least some of these patrons made their burial in their ex-slaves’ tomb a condition for manumitting them.Footnote 127

One of many cases is Tomb 87 in the Isola Sacra, the necropolis of Portus, the ancient port city of Rome. It comprised a wide range of different types and sizes of tombs, among which the ‘house’ or ‘terraced’ tombs are the most prominent.Footnote 128 Their patrons were mostly freedpeople, but some were freeborn, probably in the first generation. Tomb 87 was erected as a medium-sized but delicately decorated terraced tomb around 140, and consisted of the actual tomb building, a forecourt and two built dining couches in front of the entrance.Footnote 129 The tomb featured two tituli with identical texts, above the street entrance to the courtyard and above the door of the cella, telling us that it was erected by P. Varius Ampelus and Varia Ennuchis for themselves as well as their freeborn patron Varia Servanda, and their freedpeople and their descendants.Footnote 130 Even though Servanda’s name is written in smaller letters than the names of her liberti, it is notable that she is mentioned at all in the titulus. Moreover, she received the place of honour in the central niche of the rear wall, with another inscription giving her name,Footnote 131 while the founders of the tomb and later occupants did not label their own ollae.Footnote 132

A similar arrangement is documented in a Trajanic funerary altar of the Iunii in the Capitoline Museum, which was set up by Iunia Venusta for her patron, her husband, a son and a daughter (Figure 3.9).Footnote 133 Portraits of all four are arranged carefully. The patron is depicted alone in the tympanum, while husband and children feature in the main relief below.

Figure 3.9 Funerary altar of the Iunii family, Trajanic; Rome, Museo Nazionale Centrale Montemartini 2886 (NCE 2969)

Such examples also confirm literary sources that tell us how close could be the relationship between owner and slave, and patron and freedperson.Footnote 134 Freedpeople belonged to the familia of their patrons, whose family name, the nomen gentile, they adopted on manumission. Their patrons could therefore stand in for their ancestors, as Lauren Petersen and others have observed.Footnote 135 In the case of women, one might object that they do not make proper ancestry. Yet we have seen their importance in the Licinian tomb and for aristocratic families.Footnote 136 Moreover, in the freedman milieu, they bestowed their family name on their ex-slaves as much as male patrons did, a name that the Varii in Isola Sacra Tomb 87 treasured enough to deny burial to any external heir; that is, an heir with a different family name. The general idea of creating a family line is beautifully illustrated by the Iunii altar (Figure 3.9). The portraits are clearly differentiated in age, with the patron shown as a bald old man and the husband as an adult between his two children. Moreover, all four are depicted in bust format, which is clearly not meant to portray the living, thus hinting at the imagines maiorum of the aristocracy.Footnote 137 The allusion to ancestral portraits, the hierarchical arrangement of the portraits and the explicit portrayal as three generations leave no doubt about Iunia’s intention to present here a multigenerational family with her (their?) patron featuring as its founder.

A patron did not always have to be buried in a freedman’s tomb in order to serve as an ancestor. In the splendid mausoleum of C. Valerius Herma in the necropolis underneath St Peter’s, the patron was perhaps depicted in the rich stucco decoration covering the walls.Footnote 138 The western wall features three niches in which the tomb’s founder, his wife Flavia Olympias and their daughter Valeria Maxima are portrayed in the form of statuettes on pedestals, alluding to both public statue honours (which they probably never received) and funerary statues, which could fulfil a similar role (Figure 3.10).Footnote 139 The eastern wall opposite features only one equivalent niche in which the stucco statuette on a pedestal depicts a balding elderly man, whose age and beardlessness suggest that he belongs to a previous generation (Figure 3.11).Footnote 140 As inscriptions are lacking, it cannot be ruled out that the statuette depicts Herma’s natural father, but this is unlikely, and not only because Herma did not legally have a father. The decorative programme does not look like it is ruled by sentimental impulses. The location of this portrait – at a distance, opposite the family and alone on its wall – is reminiscent of the likeness of the Iunii patron on the altar, and suggests that he is in fact Herma’s patron, who would have taken on the role Pompey played in the tomb of the Licinii, as it were.

Figure 3.10 Mausoleum of C. Valerius Herma (Mausoleum H, around 160 CE) in the necropolis underneath St Peter’s, west wall

Figure 3.11 Mausoleum of C. Valerius Herma (Mausoleum H) in the necropolis underneath St Peter’s, east wall

Freedmen as Pseudo-descendants

Conversely, and for the same reasons, freedmen could guarantee the continuity of a family name when there was no natural heir.Footnote 141 Herma’s tomb is again an excellent example.

The Tomb of C. Valerius Herma (Mausoleum H) in Vaticano

Herma’s mausoleum is worth studying in more detail, as no other sub-elite tomb allows for so much detail of the history of its usage to be gleaned from the surviving evidence.Footnote 142 The necropolis, situated on the slope of the Vatican Hill just north of the Circus of Nero and the via Cornelia, was remarkably well preserved by the basilica of St Peter’s that Constantine built over it, since the tombs had to be filled in to create a platform for the church. The area had long been imperial property, and it is fitting that the necropolis was used by many imperial and other wealthy freedmen.Footnote 143

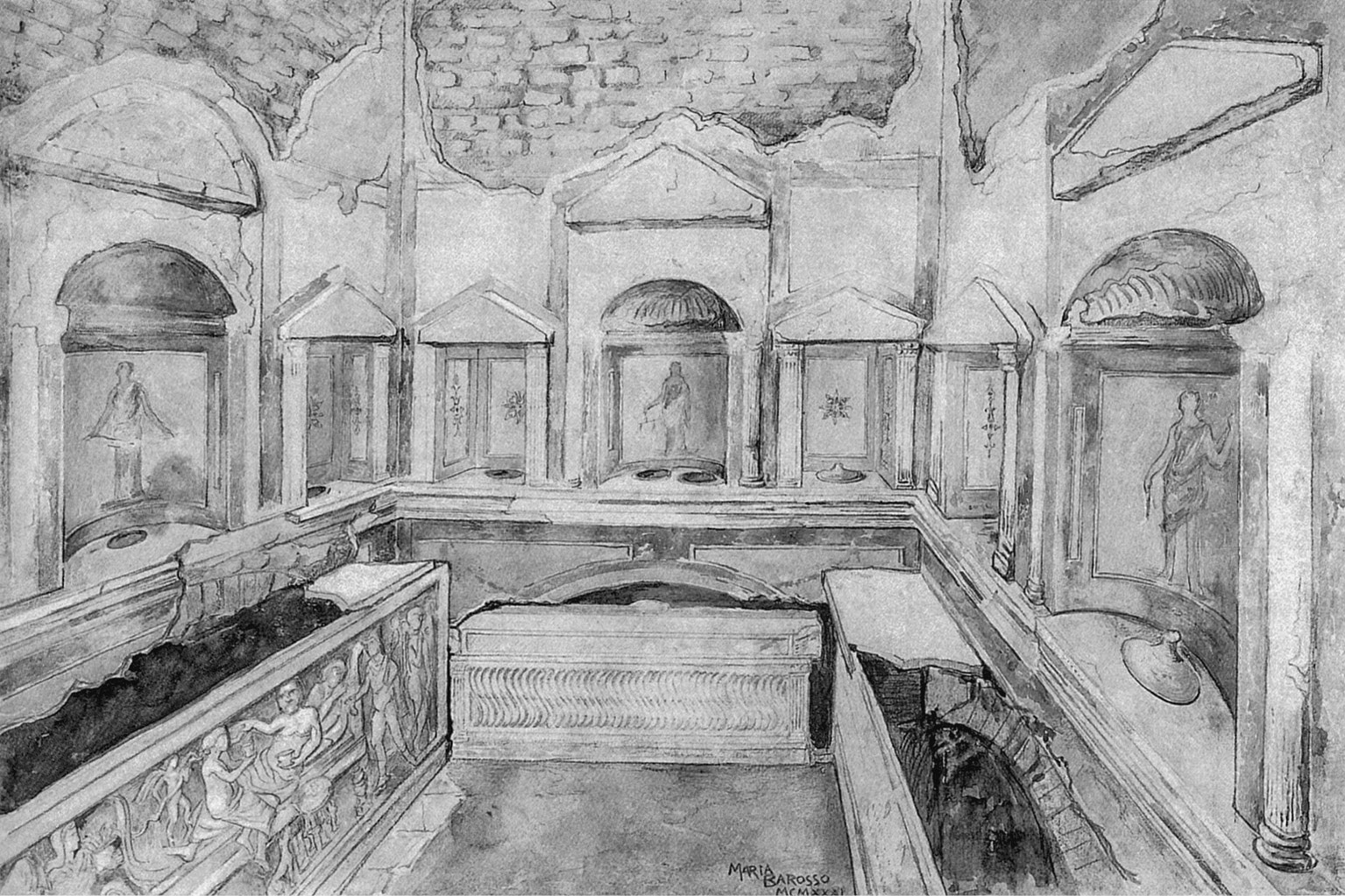

Herma founded his particularly luxurious tomb around 160, when his wife and two children had already died, and it was probably their death that instigated the erection of the mausoleum.Footnote 144 One entered the tomb through an asymmetrical forecourt with twenty niches of two ollae each. The tomb’s façade was built of the finest brickwork, decorated with four pilasters with marble bases and capitals. A large marble titulus, as wide as the door and framed by two pilasters, features above the entrance. The interior consists of a large main chamber and a smaller adjacent room extending westward to pass underneath the stairs to the roof terrace. The entrance wall was covered with twelve niches for twenty-four ollae, while the rest of the chamber was adorned by a particularly rich stucco decoration of aediculae with figures in high relief alternating with rectangular niches for further urns above a dado that contained arcosolia for inhumation (Figures 3.10 and 3.11). The adjacent room featured the same type of decoration only on its north wall.

An unusually large number of inscriptions allows for the partial reconstruction of the tomb’s burial history (Figure 3.12). Herma’s freeborn wife, Olympias, was buried in the central arcosolium of the rear wall that was later to contain Herma’s bones too, while his children occupied the smaller flanking arcosolia, all covered with inscribed marble slabs of identical design and workmanship (a–c).Footnote 145 After his wife’s death, Herma does not seem to have remarried. He buried an alumnus, Valerius Asiaticus, aged four, and donated the space for the burial of another, C. Appaienus Castus, who died aged eight, in front of the entrance wall (d–e).Footnote 146 One Valeria Asia, most likely Asiaticus’ mother, was commemorated and buried in the arcosolium in the small annex’s north wall by (her husband?) Valerius Princeps (f). The style of the inscription, almost identical to those of Herma and his family, suggests that her burial was among the earliest in the tomb. Because of the prominent location, Eck suspected that Princeps may have been Herma’s brother.Footnote 147 It is notable that no involvement of Herma is mentioned, so that Princeps may have had the right to burial there either through a family relationship or, less likely chronologically, as an heir.Footnote 148

Figure 3.12 Mausoleum of C. Valerius Herma (Mausoleum H) in the necropolis underneath St Peter’s, distribution of named burials within the chamber

After Herma’s own departure, the tomb was inherited by some of his freedmen. A certain Valerius Philomelus and his wife Valeria Galatia, surely his liberti, donated or sold the western part to their ‘well-deserving friend’ (locum obt(ulerunt) Valerii Philumenus et Galatia amico bene merenti) T. Pompeius Successus, who buried several children within and in front of the western wall.Footnote 149 Successus himself is likely to have been buried with his homonymous son in the north-western arcosolium, which also carries his name (α).Footnote 150 In the second quarter of the third century, the marble sarcophagus of Pompeia Maritima, suitably decorated with sea creatures and her portrait, was set up by her son, probably against the southern part of the west wall, thus leaving visible Successus’ name and the inscription attesting to rightful ownership (δ).Footnote 151 Later, this part of the tomb must have been inherited by external heirs, who placed two sarcophagi in front of the northern part of the western wall. The first one, a large lenos showing lions savaging their prey, was dedicated to T. Caesennius Severianus by his sons Faustinus Pompeianus and Faustinus Rufinus (ε).Footnote 152 As the name Pompeianus suggests, there may have been a family relationship between the Pompeii and their late heirs, potentially through the female line.Footnote 153

Philomelus and Galatia do not appear again in the epigraphic record, so it is not clear whether they inherited the entire tomb and used the rest of the space for themselves, or whether they only inherited the western part and built a tomb for themselves elsewhere.Footnote 154 Yet it seems clear that the main part of the mausoleum continued to be used by Valerii. Unfortunately, though further Valerii are commemorated by inscriptions, most of these cannot be dated precisely. One Valerius Valens and his son Valerius Dionysius may have been buried in the arcosolium of the western wall, in two terracotta sarcophagi covered by the inscribed tabula (g).Footnote 155 Because of the relatively prominent position within the tomb, we may assume that they were heirs of either Herma or his heirs. If Eck’s restoration of another inscription is correct, an evocatus C. Valerius Iulianus buried his daughter in an unknown location in the tomb (h). He may have been a freeborn son of one of Herma’s freedman heirs, whose rank in the military corps required at least sixteen years of service, so that the burial did not occur before the early third century.Footnote 156 The third century saw continued burial activity in an orderly manner, both in simple terracotta sarcophagi and ‘bench-graves’ and in marble sarcophagi.Footnote 157 In the 270s, Valeria Florentina set up an inscribed hunting sarcophagus for her husband Valerius Vasatulus in the left-hand corner in front of Caesennius’ casket (i), which confirms that the tomb was still in use by Valerii at that time.Footnote 158

The mausoleum of the Valerii is a rare well-documented example of a family tomb founded by a rich freedman that was used continuously over more than 100 years by parts of his familia. Notably, burial took place in a very orderly way; it occurred solely in those parts of the tomb that were inherited by the user group; and only a limited number of people were actually admitted for burial. The most prominent part of the tomb remained in the hands of Valerii, although they were not natural descendants of Herma, and it is also highly doubtful that they were all agnatic descendants of his heirs: Vasatulus’ wife has the same nomen gentile as her husband and confirms that we are still looking at the freedman milieu.

Over all those years, the tomb façade boasted its original titulus and the interior decoration remained unchanged, even though its third-century occupants were obviously wealthy. Herma’s arcosolium and inscription remained visible until a very late stage, and his family’s portraits continued to be on display. They included not just a relief in front of the tomb and the stucco relief portraits (Figures 3.11 and 3.12), but also stucco portraits in the round, including those of Flavia Olympias and Valeria Maxima.Footnote 159 The exact purpose of the death masks of a man (possibly Valerius Herma) and two children is unclear, but the rarely attested practice again harks back to aristocratic tradition.Footnote 160 Whether fragments of gypsum busts also depicted members of the founder’s generation is unclear, but the gilded stucco portrait of a boy with a youth lock of mid to late Severan dateFootnote 161 demonstrates that the heirs of this tomb continued to set up portraits just like the Calpurnii had done in the Licinian tomb. Herma’s later heirs were surely proud of the richly furnished mausoleum, but also of its long-standing tradition and age. In the same way as Herma’s patron had served the tomb’s founder as ancestor, Herma later fulfilled this role for the occupants of future generations. Herma and his family had become the founders of a multigenerational freedman ‘family line’ that replaced natural kin, carried on his name, kept alive his memory as founder and honoured his tomb.

The history of no other tomb’s usage can be reconstructed with as much precision and detail as that of the Valerii, but a few additional examples can demonstrate that the observed burial patterns and the ideology behind them were typical, and only their documentation is unique.

Isola Sacra, Tomb of the Terentii (11)

Tomb 11 in the Isola Sacra was erected around 135–40 in a slightly oblique angle to, but facing, the road (Figure 3.13).Footnote 162 Of its original Greek titulus, only the bottom right part is preserved and legible.Footnote 163 It mentions a [Th]amyres pater, perhaps a son, followed by a daughter and mother. At least the latter two remained anonymous, which makes the focus on family rather than individuals even more obvious. All other epigraphic evidence belongs to a later phase of the tomb. After some time, when also the level of the ground around the tomb had risen, a small forecourt was added to the building. It seems likely that a Latin titulus with a dedication by C. Terentius Eutychus or Eutychianus to his wife Su[l]picia Acte, his son C. Terentius Felix and his natural brother C. Terentius Rufus, as well as libertis libertabusque posterisque eorum, was affixed to this forecourt.Footnote 164 Inside the tomb, which was originally designed for both incineration and inhumation, sarcophagi and pseudo-sarcophagi were added. The first was an inscribed, marble-clad pseudo-sarcophagus in front of the right-hand wall that was originally dedicated by Terentius Vitalis to (his wife?) Terentia Kallotyche and her or their children.Footnote 165 Later, the name Vitalis was replaced by that of Lucifer, and an et added in front of Kallotyche’s name, so that the inscription now reads somewhat oddly: Terentius Lucifer et Terenteae Kallotyceni. After this pseudo-sarcophagus, a strigilated uninscribed marble sarcophagus that eventually contained two bodies was set inside the rear arcosolium, which had to be extended on both sides in order to contain the casket. Finally, another pseudo-sarcophagus, decorated at its front with a banqueting scene, was built in front of the left-hand wall.Footnote 166 It shows among other figures a couch with a sleeping woman and a reclining man holding a kantharos and a wreath, and another, semi-nude woman sitting on the couch and presenting him with a cup. The hairstyles of the women suggest a date for the relief in the late Antonine period,Footnote 167 providing a terminus ante quem for the other burials. A tabula commemorates a dedication to C. Terentius Felix and his wife Ulpia Chrysopolis by C. Terentius Lucifer and his colliberti and coheres. This Lucifer is highly likely to be the one we have already met, while Felix is likely to be the son of Eutych[ian]us featuring in the entrance titulus.Footnote 168

Figure 3.13 Mausoleum of the Terentii family (Isola Sacra Tomb 11), founded around 140 CE

From this evidence, the history of Tomb 11 can be reconstructed with varying degrees of certainty. The date when C. Terentius Eutych[ian]us extended an existing tomb and added a secondary titulus to it has not been established precisely by archaeology, but was prior to the elevation of the terrain in the wake of the resurfacing of the road.Footnote 169 He and his wife were almost certainly buried by their son, C. Terentius Felix, and one would assume that, as they extended the tomb and could be regarded as (re-)founders, they were buried in the most prominent location still available. The strigilis sarcophagus occupies the most privileged position, but seems too small for a couple of adults, and is said to have contained the skeletons of youngsters.Footnote 170 It is therefore tempting to think that Eutych[ian]us and his wife were buried in the left-hand pseudo-sarcophagus. If this is the case, the tomb was used by Terentii before the two took over and extended the mausoleum, since Terentius Vitalis’ pseudo-sarcophagus on the right predates both the strigilis sarcophagus and its counterpart on the left. While we cannot prove that the original founders of the tomb were already Terentii, this is surely possible, and it is notable that Eutych[ian]us did not remove or cover the original titulus above the main entrance to the mausoleum. His son Felix and his wife Ulpia Chrysopolis must have inherited the tomb, but died without children, and were therefore buried by their freedman and heir Lucifer in an unspecified place, possibly in the courtyard.

According to the epitaph for Felix and his wife, Lucifer was not the tomb’s only heir, but probably its main one, and was certainly determined to leave a mark. For his own burial, he chose the existing pseudo-sarcophagus on the right, erasing its original dedicant’s name. This was certainly not de rigueur, but the violation was perhaps not quite as ruthless as one might think. Vitalis does not specify his relationship with Kallotyche, and the inscription leaves it open whether or not he intended to be inhumed in the place as well. Lucifer’s alteration is minimal, only replacing Vitalis’ cognomen and adding an et. The grammar is clearly not correct here and one could amend the inscription in two possible ways. One could either go by the nominative of Lucifer’s name and ignore the et, in which case he would appear to be the donor; but one could also ignore the nominative, already predetermined by the remaining nomen gentile of the original inscription, and focus on the et, which only makes sense if Lucifer was to be buried in the same grave. This intention seems beyond doubt and Lucifer may have liked sitting on the fence with the present formula. His relation to Kallotyche is as uncertain as that of Vitalis, but since her children were admitted to burial in the casket as well, Lucifer may in fact have been one of them.Footnote 171

The Iulii Plot on the Via Appia

An interesting case is also attested by six altars and a tabula from a plot at the first mile of the Appia, close to the so-called ‘columbarium of the liberti of Augustus’. As Dietrich Boschung first recognised, these attest to the burial of several generations of (imperial) freedmen and their descendants,Footnote 172 but also allow unique insight into the way a burial plot, apparently of considerable size, was managed and passed on to later heirs (Stemma 4). The first generation attested is represented by (C.) Iulius Eutactus and C. Iulius Theophilus, who permitted the burial of C. Iulius Atimetus, his wife, her patron and their delicatus (a young boy kept for amusement).Footnote 173 Next, the mother of one-year-old C. Signius C. f. Zoilos obtained permission from Theophilus and two other CC. Iulii, Oriens and Peculiaris, to bury her son. It may be concluded that Eutactus had died in the meantime and left his share in the plot to the two men.Footnote 174 In the next altar, these two are again giving permission, but Theophilus is missing.Footnote 175 He may now have died as well and left his share to three other Julii who join in the permission, Anicetus, formerly Theophilus’ dispensator and so surely his libertus, Lalus Theophili libertus and Anthus, whose relationship with Theophilus remains unclear.Footnote 176 Next, Peculiaris died and was replaced by Iulius Pyrriches.Footnote 177 The final group of socii, attested on an altar from the first quarter of the second century, consists of Lalus and the daughters and heirs of his socii: Iulia Hieria, daughter of Oriens; Iulia Ingenua, daughter of Anicetus; and Iulia Hieria, daughter of Anthus.Footnote 178 In at least two instances we also have evidence that the heirs of the plot cordoned off an area for their own family’s burial.Footnote 179 While not all individuals commemorated share the same nomen gentile, the non-Iulii can be identified as being related to Iulii by marriage, and it is very clear that the socii made an effort to ensure that the burial plot passed on to heirs of the same family name.

Stemma 4 Changing ownership of a funerary precinct of Iulii near the first milestone of the via Appia as attested by permissions given for burial

Consortium Tomb on the Via Appia and Other Renovations

This same intention is made explicit in another inscription that was found near the Porta San Sebastiano on the Appia and provides us with the following information.Footnote 180 The now-lost tomb was founded in 3 BCE by a consortium of four men and a woman, including L. Maelius Papia and Maelia Hilara, who may have been his wife and either his fellow freedwoman or his own former slave. The socii dedicated the monument to their male and female ex-slaves, stating explicitly that this was done in order to preserve their family names:

Lentulo et Corvino | Messala co(n)s(ulibus) | qui hoc monimentum(!) aedificaverunt cum ustrina | L(ucius) Maelius Papia et Maelia Hilara et Rocius Surus et M(arcus) Caesennius et Furius | Bucconius hoc monimentum(!) libertis libertabus ut de nomine non exeat | ita qui testamento scripti fuerint |

In the consulship of Lentulus and Corvinus Messala. Those who erected this monument with ustrinum, L. Maelius Papia and Maelia Hilara and Rocius Surus and M. Caesennius and Furius Bucconius, (dedicated) this monument to their freedmen (and) freedwomen, so that (it) will not go out of the name; so they have written in their will.

In 81, the complex was extended by a plot of land opposite, and the only individuals mentioned by name are one L. Maelius Successus and his mother Maelia Syntychene. Their names not only confirm that that of the Maelii had been preserved for over eighty years, but also that this was done through freedman pseudo-genealogy, since Successus bears the same nomen gentile as his mother. Finally, in 110 the tomb had to be renovated, and we are again given a list of names of the individuals involved. They include some new ones, but also three Maelii, one Furius and one Rocia, whose nomina had all featured in the original, by now over 110-year-old list of founders. Their aim to preserve their family names, despite their tomb or plot being owned by a consortium and despite their apparent lack of (legitimate) children, had been achieved, with impressive results.

Similar intentions are occasionally found in other tituli where a tomb is left to freedpeople with the explicit intention of preserving the family name(s). In CIL 6.26940 (p. 3918), Terentia Secundilla specifies that the tomb must not go out of the name of her male and female ex-slaves and their offspring (ita ne de nomine libertorum libertarum<q>ue meorum posterisqu(e) eorum exeat). In CIL 6.22208, one L. Marius Felix builds a tomb for his patrons as well as for himself and his freedpeople and their offspring ita ne unquam de nomine familiae nostrae hic monument[um exeat]. In CIL 6.1521, the concern is about several family names, most likely because we are dealing with a family comprising imperial freedmen with different names, whose own freedpeople would thus equally carry different names.Footnote 181 In CIL 6.22303, one Mattius Adiutor erected his tomb while still alive for himself and his freedpeople and their offspring for the same reason. The same expectation follows the libertis libertabusque formula in some other cases even when there is, or is hoped to be in the future, natural offspring.Footnote 182

In other cases, the renovation of tombs, which normally required permission from the pontifex maximus, the emperor or a magistrate and was therefore sometimes recorded in an inscription,Footnote 183 attests to the long life of a tomb. The Roman knight L. Salvius [---]ens renovated a tomb, probably around the middle of the third century, to be used by his family, their descendants, their freedmen and freedwomen and their offspring.Footnote 184 The tomb is unfortunately lost, but when Salvius refurbished the tomb, he erased and recarved the titulus except for the final line with the measurements of the plot, which was executed in beautiful letters of the early second century. While it cannot be excluded that he was given the tomb because it had been abandoned for some time and no heirs survived, it is equally possible that it was his ancestral mausoleum.Footnote 185

A marble block from a round tomb at the second mile of the via Latina was erected by C. Iulius Divi Aug. l. Delphus Maecenatianus, who must have been the slave of first Maecenas and later Augustus, for himself, his wife (probably his liberta) and their freeborn daughter. Around a century later, a certain C. Iulius Trophimas, most likely a descendant of one of their liberti, restored (refecit) the tomb for himself, his descendants and his freedpeople.Footnote 186 In this case, the original inscription was not erased but merely supplemented, suggesting that pride over the tomb’s long history and the longevity of the familia was part of the message.

Equestrian Descendants

Arguably, pride in a family tomb becomes most obvious within the freedmen milieu where a descendant achieved further advancement by gaining the status of a knight, but still preferred burial in the family mausoleum. In Ostia’s Porta Romana necropolis, for instance, a certain L. Combarisius Hermianus erected a tomb for himself, his wife and his children as well as his brother.Footnote 187 He was a member of the freedman college of augustales and appears in a list of 196 CE. Through inscriptions from within the tomb, at least three more Combarisii are attested. One of them, perhaps the grandson of the founder, was a Roman knight who had held all of the most prestigious offices at Ostia and was pontifex Laurentium Lavinatium.Footnote 188 Since these offices were only available to the rich, he clearly had the means to erect a tomb for himself elsewhere. And yet he chose to be buried in his family mausoleum, not ashamed of his servile heritage but proud of his ancestors, who had made it from slaves to eminent citizens of Ostia and managed to acquire a burial plot in one of the most prominent locations available.

In another case the evidence looks more elusive, as we have lost not only the tomb but also the inscribed objects in question, but the situation seems to be similar to that of the Combarisii. The tomb near Portus is described by the seventeenth-century sources as particularly impressive.Footnote 189 The titulus gives the size of the unusually large plot as 89 x 29 m, and its lavish decoration included now-lost statues. Several inscribed marble sarcophagi and other objects further confirm the luxurious burial style as well as some features of the history of usage. The tomb was founded by one A. Caesennius Herma, whose patron, A. Caesennius Gallus, is known to have been legatus pro praetore in Asia Minor in 80 and 82, as well as one A. Caesennius Italicus and his wife Caesennia L. l. Erotis.Footnote 190 The exact relationship between these founders and the other Caesennii buried in the tomb is not clear, but we can see that they included liberti of the original founders. At some stage, a garland sarcophagus was dedicated to the knight L. Fabricius Caesennius Gallus by his son, who proudly lists his father’s extraordinary achievements in the epitaph, identical to those of his later peer in Ostia.Footnote 191

Families with Different Nomina Gentilicia

As already indicated, these are some of the best-documented examples of the general ideology I want to demonstrate from Rome and its port cities. Even the relatively well-known necropoleis of Ostia and Porto suffered late antique looting; the modern excavations also paid little attention to contextual detail. For all too long, inscriptions have been treated simply as texts rather than as objects that give away their full message only in the context in which they used to be viewed. Yet it is not only poor preservation or documentation that prevents us from tracing the history of mausolea in detail. Few tombs from Rome and its vicinity are as well-known as those excavated underneath St Peter’s Basilica and the papal palaces, and among these Herma’s has yielded by far the largest number of inscriptions. In most tombs, later generations did not feel the need to set up epitaphs, nor even tabellae marking individual graves.

Admittedly, especially when we do not know the exact original location of inscriptions, even many instances where multiple epitaphs are preserved can look rather messy. Nevertheless, there is no need to conclude that this is the result of carelessness, or even anarchy and usurpation. Where we gain some insight into the way a tomb was used and passed on, this process is normally guided by clear rules. For a range of reasons, parts of a tomb could be given over to a family with a different nomen, usually relatives of a wife or friends, amici, of the heirs, as was the case with Herma’s tomb. The desire to keep the tomb in the family name could recede behind other needs (such as financial ones) or desires, especially that to pass on the tomb within the natural family even when this family does not share the same name. This is the case when daughters inherit, but also within families of imperial libertini, whose members were often enfranchised at different times and by different emperors, and thus given different nomina. Let us look at two examples.

Mausoleum F in Vaticano

In Mausoleum F of the Vatican necropolis, erected in the early Antonine period with an extraordinary façade decorated with multicoloured brick ornaments, the single large interior again provided for inhumation in arcosolia and incinerated remains in ollae and marble urns in the brightly coloured decorated walls above (Figure 3.14).Footnote 192 The main titulus of the tomb is not preserved, but the epigraphic evidence from inside suggests that it was founded by M. Caetennius Antigonus and his wife Tullia Secunda, who were commemorated on an altar that stood in the centre of the space (a).Footnote 193 Tullia already had a burial place assigned in her parents’ tomb, Mausoleum C, just a few metres down the road, but ‘moved’ into Mausoleum F together with her husband.Footnote 194 Before setting up their own altar, however, Antigonus dedicated a cinerary urn to his patron M. Caetennius Chryseros, who appears to be the first person buried in the tomb.Footnote 195 This suggests that Antigonus may have been freed on his master’s death with the obligation to provide him with an adequate burial place. The urn was found not in the central niche of the back wall but to the right of it (b), and it cannot be excluded that Antigonus was not as keen to capitalise on his pseudo-ancestry in the same way as others were. However, is it really plausible to assume that Antigonus assigned his patron a lateral place when the entire tomb was still empty and Antigonus did not intend to use the central niche for himself?Footnote 196 Urns are relatively easy to move around and the lateral niche also seems too narrow for Chryseros’ urn.Footnote 197 In light of the use of tombs as discussed previously, it is therefore possible, if not likely, that the patron’s urn was originally set up in the centre, in the background of and in the line of sight of the founders’ altar, and flanked by their now-lost cineraria.

Figure 3.14 Mausoleum of the Caetennii and Tullii (Mausoleum F, early Antonine) underneath St Peter’s, distribution of named burials within the chamber

Two further marble urns were dedicated to Caetennii by their colliberti and set up in prominent positions, namely in the central niche of the left, western wall and in the upper northernmost niche of the east wall (c–d).Footnote 198 The exact relationships these people had with Antigonus and each other are not clear, but the urns are dated to the second half of the century, when Antigonus had already died.Footnote 199 It is therefore likely that they were Antigonus’ freedmen and heirs, or freedmen and heirs of his heirs.