In the previous nine chapters linguistic layers of identity were construed as separate areas of research. This organization of the epistemological construct proposed in the present monograph has distinct advantages given that the techniques deployed in the exploration of each layer differ and that there are significant differences in the focus and structure of the layers, the role of the elites and the speakers, and the intervention type. However, this does not mean that the layers are isolated and that no communication between them exists.

There are many ways in which the three layers of lexical identity are connected. Let us consider the following example. Popović (Reference Popović1955:7), writing about Serbo-Croatian, notes its connections with two groups of languages:

Sa jednima je u genetskoj vezi, tojest s njima ga vezuje zajedničko poreklo … Sa drugim jezicima nije u genetskoj vezi … ali ga je u realnu vezu dovela istorijska stvarnost: zajednički život na istom tlu … ipak se i do danas srpskohrvatski jezik tretira izolovano, kao da od vremena izdvajanja iz opšteslovenske zajednice nije primio nikakve elemente sa strane. Razume se da je ovakav lingvistički romantizam i “rasizam” jednostran i nedijalektički.

(With one group of languages there is a genetic relationship, i.e., it is tied to them through a common origin … with other languages it is not a genetic relationship … however historical reality, i.e., life together at the same territory, brought those languages together … Nevertheless, even to this day Serbo-Croatian is treated in isolation as if no elements from other sources were adopted since its separation from the common Slavic community. Needless to say, this linguistic romanticism and “racism” is one-sided and non-dialectical.)

Popović advocates the idea of the importance of lexical exchange, in addition to the deep layer, and he also expresses his negative attitudes toward conscious maneuvers in the surface layer aimed at the suppression of the importance of the exchange layer.

If we look at some concrete examples, the connection between the two layers will become more obvious. In Russian, there are pairs of word stems where one of them is originally Russian and the other is borrowed from Old Church Slavonic, e.g., Russian word: голова ‘head, anatomically’; Old Church Slavonic borrowing: глава ‘head, of a committee, etc.’ Russian word: ровный ‘even, i.e., flat’; Old Church Slavonic: равный ‘even, i.e., equal’. Most commonly in these pairs of roots, the original Russian form is more concrete and the borrowed Old Church Slavonic form more abstract. The process of borrowing (i.e., a process from the exchange layer) has eventually created a distinction in the deep layer, given that many languages will not have lexical distinctions of this kind. Similarly, in Serbo-Croatian, lexical borrowing from Turkish (of the words that eventually can be from various other Near and Middle Eastern sources) has created pairs of words, where one is either from the inherited Slavic stock or borrowed from a Western European language. In these pairs, the Turkish borrowing is stylistically marked as restricted in some way while its counterpart remains neutral, e.g., inherited Slavic oprostiti ‘to forgive’: a borrowing from Turkish halaliti ‘to forgive, restricted to the use in Islam and colloquially in some regions’, a borrowing from German klozet ‘toilet, neutral’: a borrowing from Turkish ćenifa ‘toilet, archaic or regional colloquial’.

All this is not unlike the pairs in English stemming from the Norman Conquest, where the Anglo-Saxon words typically mean something more concrete, and Old French words something more abstract (or processed, sophisticated, etc., semantically or stylistically) as in Anglo-Saxon cow, pig, deer, thinking, wish, wild versus Old French borrowings beef, pork, venison, pensive, desire, savage. Here too, a process in the exchange layer has led to language-specific distinctions in the deep layer.

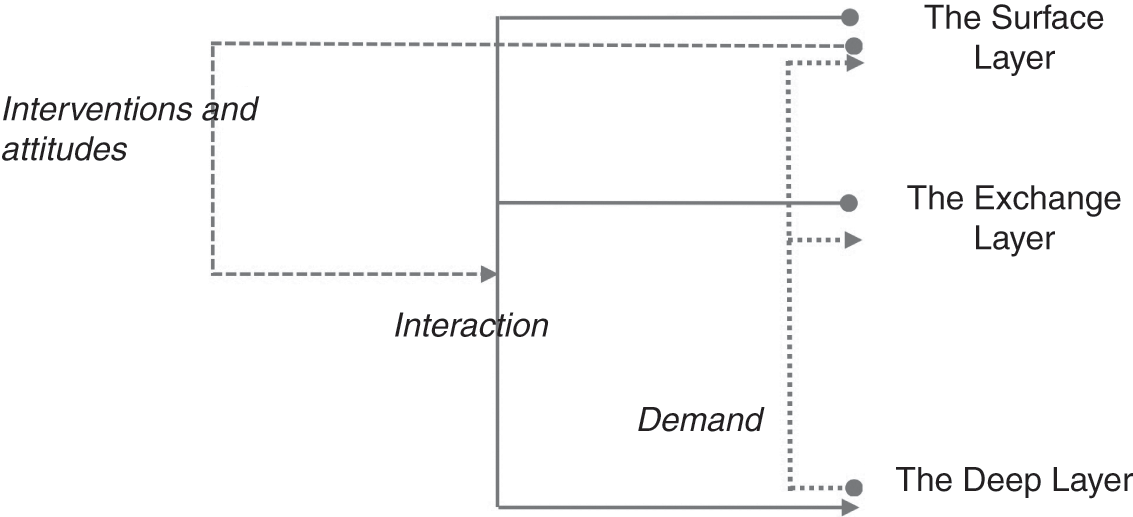

In the present chapter I will outline a unified model of interaction between the three layers. While each layer represents a distinct object of research with its specific features (as previously shown in Chapter 3 and elaborated in Chapters 4–6 for the deep, 7–9 for the exchange, and 10–12 for the surface layer), there still exists the need to explore the interaction between them, given that some phenomena cut across the borders of the layers. Sociocultural and technological changes in the environment in part trigger the movements in the exchange and surface layers, but they are also determined by the fact that the lexical material in the deep layer is insufficient to accommodate the changes in the environment. The need for information from the deep layer is thus a stimulus for the processes of the other two layers. These two layers, on the other hand, are the venue where new lexical units are introduced (by lexical exchange or engineering), which eventually may lead toward rearranging the distinctions and the density of lexical fields in the deep layer. The surface layer, in turn, operates with interventions and attitudes (e.g., of purism or laissez-faireism) on the material from the exchange layer (such as acceptable and not acceptable introductions of new words, delegitimization of existing words) or directly on the material of the deep layer (in case no borrowed lexemes are encompassed by the maneuver, e.g., the one in which the elites postulate incorrect use of an inherited Slavic word). These relations are depicted in Figure 13.1.

Figure 13.1 Interaction between the three lexical layers of identity

The interaction of the layers was evident in the previously discussed nineteenth- and late twentieth-century Croatian maneuvers in the surface layer (more information can be found in Thomas, Reference Thomas1988 and Langston and Peti-Stantić, Reference Langston and Anita2014). There was a demand for new lexical items that were not available in the deep layer, or for a redistribution of the existing lexical items. Both were triggered by a broader environment and its sociopolitical and technological changes. Maneuvers of lexical planning intended to meet those demands are confronted with the attitudes of the speakers. Some of them have stabilized and become a constituent of the deep layer; in case of others, either an exchange lexical item or status quo have prevailed and an engineered lexicon has not been accepted. As previously emphasized, the surface and the exchange layers operate in conjunction with the deep layer, which in turn eventually includes not only the inherited lexicon that evolves over time but also borrowed and engineered words that have stabilized in the deep layer.

The layers are also connected at the level of speakers. Speakers are culturally defined by all three lexical layers concurrently. They function in the deep layer generally without agency and cognizance of what is determining them culturally. They are generally cognizant, but their agency is extremely limited in the exchange layer, while the surface layer features their full agency and cognizance. What connects the three layers are the mental lexicons of the speakers and their linguistic behavior pertaining to lexical choices and evaluations alike. That is where they coexist and interact. The features of the words, such as borrowed or inherited, standard or non-standard, are linked in the speakers’ mental lexicons with the words in the deep layer, which carve out the conceptual sphere in sharing it with other words, that have their own internal semantic structure, that participate in idioms, lexical relations, word formation, and associative networks. Any choice that speakers make in using or not using the words affected by a maneuver in the surface layer is also related to the other two layers. It contributes to a broader or narrower use of the words from the deep layer, and it often concerns the features from the exchange layer (e.g., in the case that the maneuver is a purist one).

To demonstrate this, I will use an example from the 1990s, a real-life laboratory of lexical changes in all Slavic countries (given the transition from communist systems and planned economy to capitalism and free-market economy along with all technological and lifestyle changes that were also happening elsewhere). These changes were particularly far-reaching in Serbo-Croatian, which combined these changes with the revival of nationalism and religious zealotism. I will take the following three Croatian word cohorts that came under the spotlight during the 1990s and that exemplify a range of possible situations in lexical engineering, refereeing, and the dynamics of the relationship between the elites and general speakers: sučelje:interfejs ‘interface’, privreda:ekonomija:gospodarstvo ‘economy’, pasoš:putovnica ‘passport’.

The word for computer interface was a lexical lacuna in the deep layer, which needed to be filled once computers became widely used by the general population of the speakers. This triggered the lexical borrowing of the English term, which also activated the exchange layer, but there was also a maneuver in the surface layer to use a word created from the existing material (which again involves the deep layer), namely combining: su- ‘next to (prefix)’, čelo ‘front (of a head)’, and ‘-e ‘object, device (suffix)’. The lexical planning maneuver in the surface layer involved negative lexical refereeing of the borrowed lexical item and the engineering of the new word. Speakers were confronted with the possibility of accepting the lexical maneuver (which would then block the item in the exchange layer) or rejecting it and using the borrowed lexical item (which would block the surface-layer maneuver). In the end, both lexical items were preserved and the attitudes of the speakers created a type of variation which culturally defined them, as they had a choice of using either of the two terms or both of them. This choice process then varies from speaker to speaker and from situation to situation. It should be clear by now that the situation involved all three layers and their interaction.

The nest privreda:ekonomija:gospodarstvo ‘economy’ was even more complex. The pre-1990s deep-layer situation in all Serbo-Croatian variants encompassed two closely related words: privreda ‘economy’ and ekonomija ‘economics’. The first word is a nineteenth-century engineered word, which roughly means ‘contribution to the value’. The second word is a borrowing from Latin via German and French. In the 1990s there was a maneuver in Croatian to replace the word privreda with another engineered word, i.e., gospodarstvo (gospodar is ‘owner’ and -stvo is the suffix which roughly means ‘the field of’). This word was used at some point in nineteenth-century Croatian, but its revival was primarily modeled after Slovenian, which has been using that word since the nineteenth century. The sole purpose of the maneuver was to emphasize the Croatian ethnic identity at the time when the Croatian state was created – the maneuver was not purist; both involved words were ultimately of the inherited stock. The maneuver was generally accepted by the speakers of Croatian and the word privreda is not used anymore in this variant of Serbo-Croatian (it is continuously used in its other variants). However, the influence of the exchange layer and the fact that economy and economics sound similar in English brought about the same process in all variants of Serbo-Croatian. The word ekonomija is now used to mean not only ‘economics’ (which has never changed) but also ‘economy’. Eventually, the speakers of Croatian began having a deep-layer distinction for using formal gospodarstvo (from the surface layer) and informal ekonomija (from the exchange layer). Again, the example features intensive interaction of all three layers and a negotiated outcome where speakers’ attitudes operate on the elites’ maneuvers.

Finally, pasoš, a borrowed word, was used in Croatian for ‘passport’ before the 1990s, when there was a maneuver to replace it with an engineered word putovnica (put ‘trip, travel’ and –ovnica ‘document (suffix)’). The engineered word was loosely based on Slovenian potni list ‘travel document’. Its primary purpose was to emphasize the Croatian ethnic identity by using a word different from Serbian. The maneuver was eventually accepted and pasoš is used only marginally (it continues to be used in all other variants of Serbo-Croatian). Again, all three layers were involved.

The way in which the exchange layer shapes the deep layer can be seen in the differences of naming certain animals in Slavic languages, in comparison to the same process in English. In Slavic languages, where there was no interference from the exchange layer, the deep layer featured word-formation links between the name for the animal and the name for its edible meat. For example, in Russian there is свиня:свинина ‘pig:pork’, теля:телятина ‘calf:veal’, олень:оленина ‘deer:venison’, that is, names for the meat are suffixally derived from animal names. In English, in contrast, the lexical exchange induced by the Norman Conquest has eliminated these links as in pig:pork, calf:veal, deer:venison.

To demonstrate that an interaction of this kind is by no means restricted to the South Slavic or Slavic realm, one can mention a well-known example of the multiword unit silk road. The term was actually introduced by a German geographer by the name of Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877 (Waugh Reference Waugh2007:4) as Seidentraße ‘silk road’, that is, it is something that was engineered in the surface layer. It was then a part of the exchange layer to be adopted in all major languages. Curiously, one of them was Chinese which features 丝绸之路, Sīchóu zhī Lù ‘route of silk’, now a part of the deep layer, with speakers being unaware that this is not an ancient Chinese term.

There are numerous other examples like this that can demonstrate the interaction of the three layers either in the times of intensive lexical changes or in less turbulent times. It is important to understand that the general parameters of the deep or even exchange layer do not change with scores or even hundreds of words like the ones used to exemplify the interaction. The changes happen when a critical mass of words or their features is reached and it is impossible to point to its exact moment, as the change, like any other in historical linguistics, assumes a gradual process that takes prolonged periods of time to complete. General lexical distinctions in the deep layer or a general presence of a borrowed lexicon in the exchange layer (that culturally defines speakers) is still there, even after the abrupt period of changes, given that the changes affect only limited vocabulary ranges (as we could see in the example of the new Serbo-Croatian words in the 1990s that was discussed in Chapter 12).

It is also important to note that the demand from the deep layer is a reaction to triggers from the sociocultural environment (which was also apparent from the analysis in Chapter 12). These triggers range from the need to introduce new words to cover a conceptual sphere as a consequence of technological advancement, to the need to replace existing words to emphasize ethnic identity or enforce a specific form of the standard lexicon and hence linguistic authority.

Having pointed out the areas of interaction between the layers, the fact should be repeatedly stressed that each of the three layers features specific ingredients that profile the speakers’ cultural identity in a way that is different from the other two layers. Similarly, the research techniques for the study of the linguistic markers of cultural identity are different in each one of the three layers.