Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- 5 Hogarth Engraving

- 6 Lithograph

- 7 Morse Telegraph

- 8 Singer Sewing Machine

- 9 Uncle Tom's Cabin

- 10 Corset

- 11 A.G. Bell Telephone

- 12 Light Bulb

- 13 Oscar Wilde Portrait

- 14 Kodak Camera

- 15 Kinetoscope

- 16 Deerstalker Hat

- 17 Paper Print

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- About The Contributors

16 - Deerstalker Hat

from The Age of invention

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- 5 Hogarth Engraving

- 6 Lithograph

- 7 Morse Telegraph

- 8 Singer Sewing Machine

- 9 Uncle Tom's Cabin

- 10 Corset

- 11 A.G. Bell Telephone

- 12 Light Bulb

- 13 Oscar Wilde Portrait

- 14 Kodak Camera

- 15 Kinetoscope

- 16 Deerstalker Hat

- 17 Paper Print

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- About The Contributors

Summary

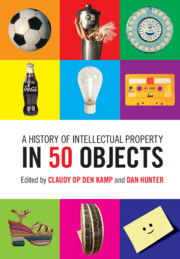

IN MILLER's CROSSING, the prohibition era gangster movie by the Coen brothers, Gabriel Byrne plays Tom Reagan, a rumpled, whiskey-soaked, antihero—the brooding right-hand man to Irish kingpin, Leo O'Bannon. Reagan's hat—a simple fedora—is more than costume or prop: it is central to his character and the narrative. In the film's title sequence, the hat blows along a forest path, caught in the breeze, dancing between the trees in what might be a fairy tale scene. Later, Tom recounts a dream to his lover Verna about walking in the woods when the wind blows his hat off; she preempts the ending: “And you chased it right? You ran and ran, and finally caught up to it… picked it up. But it wasn't a hat anymore, it had changed into something else, something wonderful.” “Nah,” he responds, “it stayed a hat and no, I didn't chase it. Nothing more foolish than a man chasing his hat.” Tom's curt, irritable dismissal is playful and sly. The Coen brothers have remained famously gnomic about the hat's significance, but its place on screen is deliberate, purposeful and integral. It is one of the most iconic hats in cinematic history. With its roots in mid-19th-century Scotland, the humble deerstalker has been transformed into “something else, something wonderful.” It has become a metonym. Show someone a picture of a fedora and they are unlikely to think: Tom Reagan. But, show someone a deerstalker?

In many respects, the deerstalker's place within this history of intellectual property is ambiguous and improbable. But that also imbues it with relevance and resonance. It shimmers, speaking not to one story but many. The story of the deerstalker is the story of Sherlock Holmes, and the story of Holmes is Scheherazadian, offering up an abundance of tales: about the contingent nature of intellectual property rights, their territoriality, and longevity; about authorship, co-creation, and the collective construction of cultural value; about copyright's public domain, and the afterlife of characters beyond the stories that define them; about intertextuality, making meaning, and making money; and, about the mysteriousness of copyright, its unknowability, and ubiquity.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects , pp. 136 - 143Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019