18.1 Introduction

Equity and justice considerations have always been central to understanding past and current forms of global climate governance as well as the motivations and goals of different actors. Climate justice scholarship has demonstrated that concerns about equity and fairness played a significant role in shaping the form, mandate, functions and development of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Mintzer, Reference Mintzer1994; Grubb, Reference Grubb1995; Paterson, 1996; Okereke, Reference Okereke2007, Reference Okereke2010). Analyses of international climate politics after the 2015 Paris Agreement suggest that equity concerns are likely to continue to occupy a vital place in future approaches through which societal transformations in the face of climate change might be managed (Okereke and Coventry, Reference Okereke and Coventry2016; Rajamani, Reference Rajamani2016).

It has long been observed that while the UNFCCC was the main structure and process for coordinating the international response to climate change, the governance of climate change has involved a multiplicity of actors exercising agency and authority in a non-hierarchical mode, (co-)creating norms across different scales (Okereke, Bulkeley and Schroeder, Reference Okereke, Bulkeley and Schroeder2009). In a sense, therefore, climate governance has always exhibited some degree of polycentricity – that is, having ‘many centres of decision-making which are formally independent of each other’ (Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren, Reference Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren1961: 831). As one might expect, contestations for justice have also been a key feature of the different arrangements for climate governance outside of the UNFCCC, even though these have received less attention compared to analyses of justice within the international climate regime. For example, Bulkeley et al. (Reference Bulkeley, Carmin, Castán Broto, Edwards and Fuller2013) and Bulkeley, Edwards and Fuller (Reference Bulkeley, Edwards and Fuller2014) have provided an important analysis of the contestations for climate justice in global cities. Justice concerns have also been analysed in the context of transnational climate networks (Lidskog and Elander, Reference Lidskog and Elander2010), urban climate adaptation (Schlosberg, Reference Schlosberg2012; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Chu and Anguelovski2016), business and corporate actors (Verbruggen, Reference Verbruggen2008; Matt and Okereke, Reference Matt, Okereke, Stephan and Lane2014) and in national climate and energy transition programmes (Newell and Phillips, Reference Newell and Phillips2016) – among several other issues, dimensions and scales.

In this chapter, I pursue two main objectives. First, I explore the influence of climate justice contestations on the emergence of polycentric governance. Second, I explore the implications of polycentric climate governance for climate justice as well as the potential role of equity in a more complex and fragmented global climate governance arrangement. With the entry into force of the Paris Agreement heralding a new, more voluntary approach to international climate cooperation (through nationally determined contributions), and with the increasing proliferation and diversity of actors in the climate governance space, it is fair to suggest that the global community has entered a new phase of more polycentric climate governance. It is therefore necessary to analyse, on the one hand, what this new era and architecture for climate governance means for climate justice and, on the other hand, how considerations of equity and fairness might impact the new polycentric climate governance arrangement.

This chapter starts with a brief discussion of the concept of climate justice, a mapping of the key dimensions of justice in climate policy and a review of some of the key themes and aspects of climate justice scholarship. Next, I consider the role of equity concerns in both facilitating and hindering polycentric climate governance, covering both the international and other levels of governance. I then discuss the implications of greater polycentricity for climate justice and equity, drawing attention to issues of effectiveness, transparency and accountability before ending with some concluding remarks.

18.2 Climate Justice and Equity

Broadly speaking, climate justice is concerned with the equitable distribution of rights, benefits, burdens and responsibilities associated with climate change, as well as the fair involvement of all stakeholders in the effort to address the challenge. Following Aristotle (Reference Aristotle1976), equity can be understood as decisions intended to prevent injustice arising from the rigid application of broad, just principles. Political justice and equity mostly sit on the same continuum and are here used interchangeably.

Reflecting its historical core framing as an international problem as well as the dominant role of the United Nations (UN) multilateral process in driving response options, the focus of the early climate justice literature was on the international level, especially on burden sharing between developed and developing countries (Agarwal and Narain, Reference Agarwal and Narain1991; Shue, Reference Shue, Hurrell and Kingsbury1992, Reference Shue1993; Grubb, Reference Grubb1995; Paterson, Reference Paterson1996a, Reference Paterson and Holden1996b, Reference Paterson, Sprinz and Luterbacher.2001; Shukla, Reference Shukla and Tóth1999). The concern for justice in the international regime is rooted in three dimensions of asymmetries, related to contributions, impacts and participation (Okereke, Reference Okereke2010). The first is asymmetry in the contribution, which recognises massive differences in the historical and current contributions of different countries to climate change. For example, the 20 largest economies in the world together account for 82 per cent of total global carbon dioxide emissions (Raupach et al., Reference Raupach, Davis and Peters2014). The United States and the European Union (EU), which account for about 10 per cent of the global population, are responsible for 24 per cent of global carbon emissions, while the whole of Africa, home to about 20 per cent of the global population, accounts for just about 3 per cent of global emissions (IPCC, Reference Edenhofer, Pichs-Madruga and Sokona2014; Wiedmann et al., Reference Wiedmann, Schandl and Lenzen2015).

The second is asymmetry in impacts, which focuses on the fact that the negative impacts of climate change will not be borne proportionately by countries (Schaeffer et al., Reference Schaeffer, Baarsch and Adams2014). A key observation in the international climate justice literature and policy discourse is that the ‘unavoidability of justice’ (Shue, Reference Shue, Hurrell and Kingsbury1992: 373) resides in the fact that climate impacts will be disproportionately borne by the poorest nations that have contributed the least to the problem. This leads to the charge that climate change involves rich countries imposing significant risks on poorer countries (Agarwal and Narain, Reference Agarwal and Narain1991; Okereke, Reference Okereke2011).

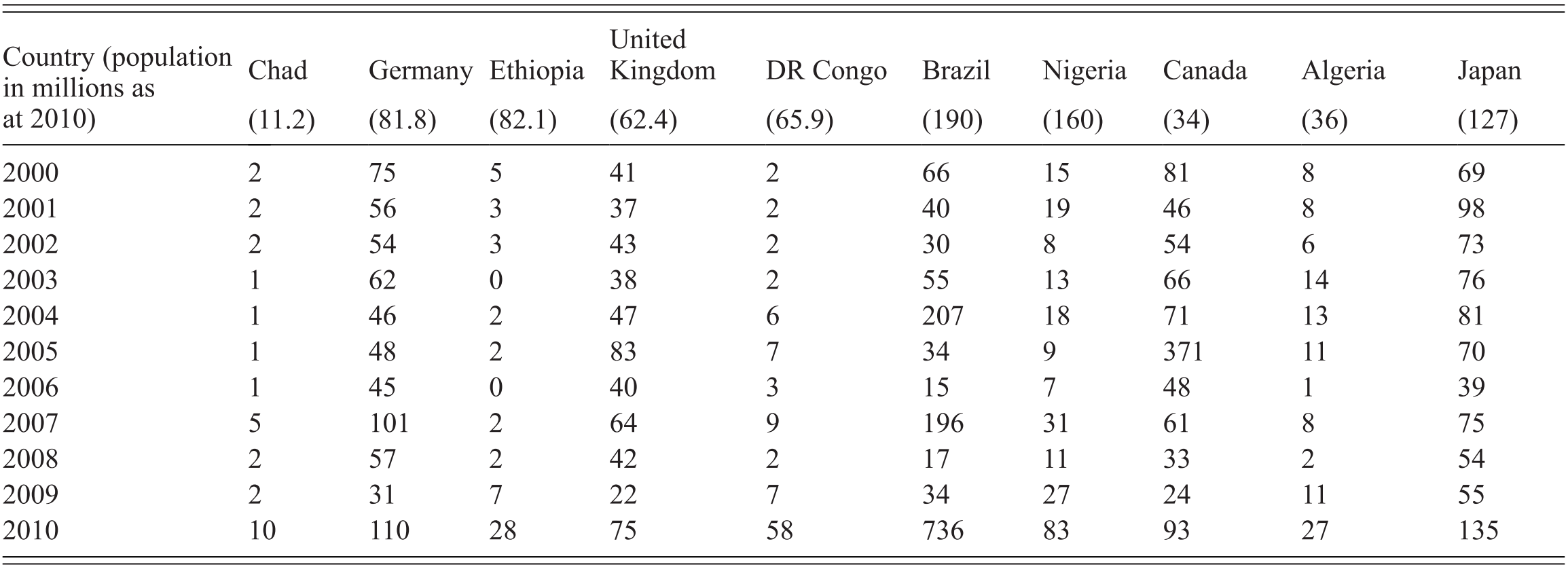

The third asymmetry relates to the ability of countries to participate in various international decision-making forums. Facing limited resources, developing countries are generally unable to attend and participate effectively in international climate meetings (Shue, Reference Shue, Hurrell and Kingsbury1992; Okereke, Reference Okereke2007; Okereke and Charlesworth, Reference Okereke, Charlesworth, Betsill, Hochstetler and Stevis2015). Besides being outnumbered, developing countries also very often lack the technical abilities and skills to prepare for and follow complex and lengthy negotiations (Okereke and Coventry, Reference Okereke and Coventry2016). The lack of meaningful participation raises the possibility that climate policies may be designed in ways that fail to address the interests of the poorest countries and, in doing so, exacerbate global inequalities. Table 18.1 presents an overview of the number of delegates attending the annual UNFCCC meetings from selected developed and developing countries (based on comparable populations). It clearly demonstrates that developing countries are vastly outnumbered in the global conferences where important decisions are made.

The early climate justice literature correctly observed that the three dimensions of asymmetry (contribution, impact and participation) that characterise climate diplomacy at the international level also apply to many other dimensions and scales, such as between present and future generations (Howarth, Reference Howarth1992; Page, Reference Page1999), between genders (Terry, Reference Terry2009) and within countries (Adger, Reference Adger2001; Baer et al., Reference Baer, Kartha, Athanasiou and Kemp-Benedict2009). A running theme in the climate justice literature in the past two decades has been the focus on analysing climate equity outside the international regime. Let me briefly highlight some of the notable dimensions.

First, following the work of Paavola and Adger (Reference Paavola and Adger2006), there has been a proliferation of literature on climate justice in the context of adaptation, reflecting the need to understand how issues of fairness are implicated at local scales of climate governance, with all the diversity and variations that characterise such geographies. More recently, there has been a growing literature on rights- and capability-based approaches to climate justice, which focus on the links between climate actions and individuals’ rights to life and well-being (Schlosberg, Reference Schlosberg2012; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Chu and Anguelovski2016). Somewhat related to adaptation is the issue of climate-induced loss and damage as well as migration, which has also begun to receive increasing attention in climate justice scholarship (Marino and Ribot, Reference Marino and Ribot2012; Cao, Wang and Cheng, Reference Cao, Wang and Cheng2016; Lees, Reference Lees2017).

Second, there has been an increasing body of literature on climate justice in the context of subnational actors, especially cities (Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Carmin, Castán Broto, Edwards and Fuller2013; Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Edwards and Fuller2014). At the same time, attention has focused on the equity implications of burgeoning transnational climate governance initiatives – such as the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership, the CDP (formerly, Carbon Disclosure Project) and the Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition – which often perform important governance functions including agenda setting, norms diffusion, verification and standard-setting (Derman, Reference Derman2014; Castro, Reference Castro2016).

Third, more light has been shed on the role of businesses, especially global corporations, in causing climate change and the need to ensure that these entities are doing their fair share in tackling climate change in the context both of mitigation and of adaptation (Heede, Reference Heede2014; Frumhoff, Heede and Oreskes, Reference Frumhoff, Heede and Oreskes2015). Related to this are the many different lawsuits that have been brought against corporations on climate change, particularly in the United States (see also Chapter 3), as well as analysis of the justice and equity implications of market-based mechanisms or policies for tackling climate change, which have also been on the increase (Peel and Osofsky, Reference Peel and Osofsky2015).

Fourth, there has been increasing recognition that contestations of climate justice frequently express themselves in several other resource politics at regional, national and local levels. Newell and Mulvaney (Reference Newell and Mulvaney2013), Baker, Newell and Phillips (Reference Baker, Newell and Phillips2014) and Bratman (Reference Bratman2015) have highlighted climate justice implications in national energy transition initiatives. Schlosberg’s (Reference Schlosberg2013) account has focused on food justice, while Gupta (Reference Gupta, Padt, Opdam, Polman and Termeer2014, Reference Gupta2015) has covered forest and water resources.

A fifth development, which is connected to many of the aforementioned dimensions, is the increasing attention paid to the need for procedural justice and participation, not with respect to states’ participation, but also with respect to broader public engagement of laypeople (Devine-Wright, Reference Devine-Wright, Richardson, Castree and Goodchild2017), citizens’ panels (Kahane and MacKinnon, Reference Kahane and MacKinnon2015), indigenous people and local communities (Schroeder, Reference Schroeder2010) and civil society groups in climate decision-making (Stevenson and Dryzek, Reference Stevenson and Dryzek2014).

The proliferation and intensification of the climate justice literature focusing on other scales of governance in addition to the international regime is a clear indication of the appreciation of the independence, rule-making authorities and impact of these climate governance nodes, and also an implicit acknowledgement that climate governance is indeed multicentred and that justice is relevant to all nodes.

18.3 Climate Equity Impact on Polycentric Climate Governance

In this section, I advance the argument that concerns for climate justice are indeed a major factor that accounts for the development of climate governance in a more polycentric direction. First, I look at the role of justice concerns in the evolution of the international climate change regime. Next, I focus on the role of justice in facilitating the profile of adaptation and loss and damage. Then I examine the role of justice in creating global carbon markets, the involvement of cities and in the proliferation of transnational climate governance.

18.3.1 Evolution of the International Climate Regime

The first and arguably still the most significant impact of equity concerns with regard to pushing global climate governance in a more polycentric direction is the role of justice-based apprehensions in mobilising developing countries to insist that the global agreement must be negotiated under the UNFCCC. Early accounts of international climate diplomacy suggest that one of the first battles fought between developed and developing countries was over the nature of the international institution that would henceforth oversee global collaboration on climate action (Mintzer, Reference Mintzer1994). In keeping with the view that climate change was essentially a technical problem requiring well-defined and limited collaboration over emission reduction technologies, developed countries very much favoured the formation of a narrow technical body (Bodansky, Reference Bodansky1993). Developing countries, for their part, maintained that climate change was a developmental problem which not only implicates fundamental issues of equity but also offers the opportunity to address broader issues of economic inequality between developed and developing countries (Bodansky, Reference Bodansky1993; Dasgupta, Reference Dasgupta, Mintzer and Leonard1994). For these reasons, they insisted that the climate negotiations should be brought under the remit of the UN. They felt that only a UN-driven process could facilitate and oversee the large scale of structural changes needed to address the scale of climate injustices. The UN was also preferred because it would offer developing country parties the ability to express their voices more effectively. Two famous quotes from top developing country negotiators captured this sentiment.

The sharing of costs and benefits implied in the conventions could significantly alter the destinies of individual countries.

The UN system permits all sides to express their opinions from a position of sovereign equality and therefore to maintain self-respect. Countries acknowledged to have dominant economic, political and military power are forced to take into account the contrasting views of many other countries, however weak those countries may be. This balance promotes a more equitable dialogue.

Once the developing countries had succeeded in bringing the climate negotiations under the UN’s ambit, they also pressed hard, on the basis of equity concerns, for the UNFCCC to have an expansive objective that accommodated the need for adaptation, food security and economic development alongside the stabilisation of greenhouse gas concentrations. Alongside other provisions on North-South technology transfer (see Chapter 15), financial assistance and capacity building, these provisions contributed to increasing the scope of the regime and creating the space for the involvement of a range of other actors in climate governance. It is conceivable that if climate negotiations had remained within the ambit of a narrow technical body as developed countries initially canvassed, much of global climate governance today would have probably consisted of a range of emission reduction technology agreements between countries, with little or no attention paid to matters such as adaptation and loss and damage (Wrathall et al., 2015).

At the same time, the replacement of the Kyoto Protocol with the Paris Agreement, with all its implications for polycentric climate governance (see Chapters 1 and 2), is also firmly rooted in concerns for justice – especially from the United States, which felt that an equitable climate agreement must create similar, if not the same, obligations for developed countries and the rest of the world, especially rapidly industrialising countries like China, India and Brazil (Okereke and Coventry, Reference Okereke and Coventry2016; Rajamani, Reference Rajamani2016). It is instructive that President Donald Trump cited equity and fairness concerns several times in his speech to announce the withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement.

18.3.2 Adaptation and Loss and Damage

An equity-fuelled emphasis on adaptation is another distinctive way in which justice concerns have facilitated more polycentric climate governance. Although the UNFCCC has always included a mention of adaptation as a key aspect of international climate governance, much of the focus on early climate diplomacy focused on mitigation (see also Chapter 17). Following the signing of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, developing countries consistently drew attention to the need to elevate climate adaptation as a key element of international climate governance. This insistence finally yielded tangible results in 2001, when the Marrakech Accords included a range of decisions on adaptation, including the undertaking to formulate the National Adaptation Programmes of Action to identify the urgent and immediate needs and priorities of the Least Developed Countries. Other landmark achievements included the establishment of the Special Climate Change Fund and the Least Developed Countries Fund, both of which were mostly targeted at funding adaptation activities in vulnerable developing countries. As of December 2016, 51 countries had submitted their National Adaptation Programme of Actions, and 46 of them have started implementing some of the National Adaptation Programme of Action activities through the funding from the Least Developed Countries Fund. Subsequently, the 2004 UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP) laid out the Buenos Aires Programme of Work on Adaptation and Response Measures, which led to the launch of the Nairobi Work Programme on impacts, vulnerability and adaptation to climate change at COP11 (2005). When parties adopted the Bali Action Plan at COP13 (2007), adaptation was placed alongside mitigation, technology transfer and finance as one of the four pillars of global climate policy.

The raised profile of adaptation has contributed significantly to increasing the multiplicity of climate governance nodes by widening the scope and range of climate governance activities and opening the space for a greater diversity of actors to play a part. Unlike climate mitigation, which focuses mainly on how we use energy, climate adaptation has covered an even wider range of activities, such as health management, rainwater harvesting, improving seed varieties, irrigation, desalination, tourism management, coastal zone management and land use planning, to mention a few (Burton et al., Reference Burton, Huq, Lim, Pilifosova and Schipper2002; Paavola and Adger, Reference Paavola and Adger2006; see also Chapter 17). At the same time, while the bulk of climate mitigation activities could be managed at the national level, climate adaptation and vulnerability management require local-level activities (Eriksen, Nightingale and Eakin, Reference Eriksen, Nightingale and Eakin2015). Furthermore, adaptation concerns, especially in developing countries, are intricately bound up with poverty reduction and efforts at the local level. These factors have all combined to expand the climate governance landscape and to draw in a diverse range of actors, such the World Health Organization and the UN Food and Agricultural Organization, into climate governance. More recently, a growing emphasis on loss and damage is drawing in more actors (e.g. the International Red Cross) and leading to the creation of additional governance platforms (e.g. the Hyogo Framework for Action) to deal with disaster risk management and climate insurance (Simon and Leck, Reference Simon and Leck2015).

18.3.3 Carbon Markets

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), a market-based mechanism for climate change mitigation created through the Kyoto Protocol, has played a significant role in widening the space for non-state actors to participate in climate governance (Green, Reference Green2013). In early international climate diplomacy, developing countries – motivated by equity concerns – demanded an international fund from which they could draw to assist them to take climate action (Dasgupta, Reference Dasgupta, Mintzer and Leonard1994; Hyder, Reference Hyder, Mintzer and Leonard1994). Following contentious negotiations, where the developed countries vehemently opposed the idea of a fund, a compromise was eventually reached to establish a mechanism – the CDM – that allowed developed country governments to invest in ‘clean development’ projects in poor countries in return for carbon credits. The carbon offsets purchased could then be used to achieve compliance for the developed countries’ Kyoto targets. The CDM was thus a product of equity-related contestation in the international regime, with developing countries seeking a fund to help address their developmental needs, and with developed countries preferring a market-based mechanism as a way of meeting this demand. One critical aspect of the CDM, which is in keeping with its market-oriented philosophy, was that it allowed for the participation of myriad companies and other entities to earn carbon credits by investing in emission reduction activities in developing countries. This provision is partly responsible for opening the climate governance space to a variety of public and private entities including firms, institutional investors and third-party validating agencies involved in the mechanism. It is evident, therefore, that the CDM has served to enhance the complexity of the climate regime (Green, Reference Green2013) and to increase the polycentric nature of global climate governance.

Alongside the larger CDM-based ‘compliance’ market, which yields units and credits that count towards developed countries’ emission reduction obligations in the UNFCCC, a voluntary carbon offset (VCO) market also emerged, which allowed individuals, companies and governments to purchase carbon offsets to mitigate their own greenhouse gas emissions. With the emergence of VCOs, myriad activities such as electricity use, holiday flights, hotel stays and car rentals were drawn in as legitimate climate actions, and alongside this arose initiatives such as the Voluntary Carbon Standard, the Climate Registry, the Chicago Climate Exchange and numerous other transnational labelling, certification, verification and trading entities that facilitate VCO transactions (Castro, Reference Castro2016).

Several organisations selling VCOs argued that it offered opportunities for rich consumers to take action on climate change, while simultaneously supporting laudable development projects, such as installing solar panels and building schools in the poor South. Furthermore, by connecting rich, climate-aware and penitent polluters in the North with poor beneficiaries in the South, the voluntary offset programme was thought to play a useful role in the ‘co-creation of global environmental values’ (Gössling et al., Reference Gössling, Haglund, Kallgren, Revahl and Hultman2009: 1). However, VCOs came under a barrage of criticism: they have been described as an emotional Band-Aid for the rich, a tool for carbon colonialism (Bachram, Reference Bachram2004) and a primitive accumulation strategy (Bumpus and Liverman, Reference Bumpus and Liverman2008) that allows the rich to exploit the poor. The point here is not to analyse the justice implications of the CDM and VCOs (as significant as they may be), but simply to assert that: (1) the creation of both the compliance and voluntary carbon markets have at least in part their rationale in equity concerns; and (2) these carbon markets have served to create self-organising, locally acting, independent actors in ways that have increased the complexity of the regime and restructured climate governance along more polycentric lines.

18.3.4 Cities

Cities have emerged as important actors on climate, and discussions about the polycentric nature of climate governance have often included reference to cities either in their individual capacities or in the form of global transnational networks (Betsill and Bulkeley, Reference Betsill and Bulkeley2006; Andonova, Betsill and Bulkeley, Reference Andonova, Betsill and Bulkeley2009; Okereke et al., Reference Okereke, Bulkeley and Schroeder2009; see also Chapter 5). Some of the notable examples of transnational city initiatives include ICLEI’s Cities for Climate Protection programme, the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, Climate Alliance and Energy Cities. Given that cities are homes to a significant percentage of the world population and most of the world’s high-polluting corporations, and considering that they are also centres of global innovation, it was unavoidable that cities would emerge as important arenas for climate governance. It is not surprising, therefore, that cities have recently been identified as a vital arena for justice contestations about both climate mitigation and adaptation activities (Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Carmin, Castán Broto, Edwards and Fuller2013; Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Edwards and Fuller2014).

Lucas (Reference Lucas2006), Byrne et al. (Reference Byrne, Ambrey and Portanger2016) and many others have noted the role of green infrastructure such as cycle lanes, green spaces and trams in promoting climate justice in cities, while Wolch, Byrne and Newell (Reference Wolch, Byrne and Newell2014) and McKendry and Janos (Reference McKendry and Janos2015), among others, have suggested that greening in cities could have the unintended consequence of promoting injustice and inequality through, for example, increasing housing cost and inducing gentrification. Dawson (Reference Dawson2010) has noted the role of cities as hotbeds for climate justice activism, and Bulkeley et al. (Reference Bulkeley, Edwards and Fuller2014: 31) have argued for an expansion of the concept of climate justice beyond fair procedure and equitable distribution of rights and responsibilities to encompass ‘“recognition” of existing forms of inequality and the ways in which climate change interventions might serve to either exacerbate or redress these underlying structural issues’. This suggests that questions of justice may manifest in unique ways and require specific contextualisation in different platforms of climate governance. Furthermore, the intense contestations for justice in cities indicate that regardless of the scale, initial rationale or origin of any given climate governance platform, it will only be a matter of time before significant and complex questions of justice arise in such arrangements. At the same time, some studies have found that despite growing visibility and claims, many cities are actually not doing much to reduce carbon emissions (Araos et al., Reference Araos, Berrang-Ford and Ford2016). This not only highlights the well-known analytical challenge of how to effectively determine the significance of many of these local level, non-traditional and ‘experimental’ climate governance initiatives, but it also raises the question of whether these initiatives actively distract attention from the pursuit of equity within the international regime.

18.4 Impact of Polycentricity on Equity

While global climate governance has always exhibited many of the characteristics associated with polycentric governance (see Chapter 1), the global community may have entered a new and distinctive era of even more polycentric climate governance. The question here is: what are the implications of this increasing polycentric climate governance on equity and vice versa? Here, at least three points can be made.

First, equity considerations remain important in the context of the Paris Agreement. The central concern here is whether a more polycentric governance structure has been secured at the expense of creating an effective regime. So far, it is known that the nationally determined contributions pledged by states, if fully implemented, fall far short of what is needed to keep the global mean temperature well below 2°C (du Pont et al., 2016). If parties fail to find a way of ratcheting up their commitments, the result will be more severe climate change impacts on the global poor, which have done the least to cause the problem. This would constitute a gross violation of the key tenet of climate justice. Furthermore, there are serious questions as to whether parties will abide by the pledges to which they have committed themselves. Evidence from the past as well as other areas of international cooperation (e.g. human rights and development assistance) suggests that states often renege on their commitments when confronted by domestic circumstances that are considered more pressing (e.g. elections, unemployment, etc.). Also, given the non-legally binding nature of the pledges, they may be easily ignored or rolled back, as is evidenced by the case of the Trump administration. In this sense, the new agreement creates challenges relating to transparency and accountability (see also Chapter 12). Some (e.g. van Asselt, Reference van Asselt2016) argue that non-state actors can play strong roles in enhancing transparency and accountability under the regime through their roles in reviewing ambition, implementation and compliance. If such roles were to be fulfilled, this would further increase the diversity of actors and push the global governance architecture towards greater polycentricity. However, it is not immediately clear what impact that will have on the actual quality of action and on climate justice.

Second, there is an important ethical question regarding whether the new voluntary and arguably more polycentric climate governance arrangement with its pledge-and-review system downgrades the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, which has been the ethical cornerstone of global climate policy. Some have indeed suggested that the new agreement, by demanding pledges from all countries (both developed and developing countries), has managed to side-step contentious equity issues that have long dogged international climate policy (Falkner, Reference Falkner2016). It would seem that the new agreement indeed envisages a diminished role for the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities by skirting over the vexed issue of differentiation between states. However, given that commitments for capacity building – and for North–South financial and technology transfer – remain in the agreement, it can be argued that the principle continues to be an important aspect of the regime post-Paris. One key aspect going forward will be how far the developed countries go to meet their obligations for financial assistance to poor countries under the new agreement. Many of these points are expected to re-emerge strongly in the context of the global stocktake in 2023, which will take place ‘in the light of equity and the best available science’ (Article 14.1 of the Paris Agreement).

Third, and going beyond the regime, there are legitimate questions as highlighted in the preceding section – especially in relation to cities and offsets – as to the extent to which these multiple sites of governance are actually resulting in meaningful climate action and carbon emissions reduction. Related to this is whether their proliferation and activities may be helping to create the illusion that something is being done and diverting attention that might be better devoted to getting traditional state actors to take ownership for and tackle the problem. It has been observed that climate voluntarism (Okereke, Reference Okereke2007), regime complexity (Green, Reference Green2013), carbon markets (Paterson, Reference Paterson1996a) and transnational climate governance (Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Edwards and Fuller2014; Castro, Reference Castro2016) are all driven by a neoliberal agenda, the ethical basis of which is not compatible with more radical interpretations of climate justice. The more radical and direct charge is that these multiple climate governance sites are in fact creating spaces for resource-rich Northern actors – including non-governmental organisations and businesses – to further exploit the poor South under the guise of taking climate action (Bachram, Reference Bachram2004; Lohmann, Reference Lohmann2011). Even when manipulation and exploitation are not the original intention, the fact that navigating multiple sites of governance is easier for developed countries (as well as non-state actors) with greater resources raises a distinctive prospect that greater regime complexity could inadvertently exacerbate existing inequalities (Benvenisti and Downs, Reference Benvenisti and Downs2007; Okereke, Reference Okereke2007). One might note, however, that equity concerns have become a stronger part of some of the transnational governance initiatives (e.g. with the Gold Standard including social impacts of offset projects). However, it is interesting that considerations of equity in these initiatives often leads to the creation of additional initiatives and standards which could in turn increase regime complexity and polycentricity.

18.5 Conclusions

This chapter has argued that equity concerns have played a major role in shaping the global climate governance architecture. More specifically, it has suggested that considerations of justice have served to push climate governance in a more polycentric direction. It was shown that the decision to negotiate the international climate agreement under the UN umbrella (rather than by a narrow technical body), the expansion of objective of the agreement signed in 1992 to include adaptation, food security and economic development, the CDM, North–South technology transfer, and capacity building among many other issues, are all rooted to more or less degrees in concerns and controversies around equity and justice. At the same time, the subsequent demise of the Kyoto Protocol model of governing and the emergence of the Paris Agreement are strongly linked to equity concerns.

Furthermore, equity considerations are also central to explaining the emergence of the voluntary carbon markets and several other subnational and transnational initiatives which legitimised the involvement of a wide diversity of actors in climate governance and in so doing rendered the global climate governance architecture more polycentric.

The relationship between equity and polycentricity is complex and even seemingly paradoxical. Equity considerations may be helping to create multiple sites of governance, which may be necessary to accommodate more actors, issues and interests. However, it is not clear that the existence of these multiple sites of governance is necessarily resulting in greater climate justice. In fact, there is a legitimate concern that some of these sites have been created or at least usurped by actors with greater resources for their own advantages and operate in ways that exacerbate existing inequalities. Climate injustices are both symptoms and magnifiers of broader structures of historical injustice and inequality that characterise the global system. Hence, unless these fundamental structural injustices are addressed, it is not clear that more or less fragmentation will address climate justice. Yet, insofar as equity concerns are inextricably tied to any climate governance arrangement, understanding the equitability of climate action (or inaction) at multiple levels, spaces and jurisdictions – and how these both link the international regime and contribute to ambitious climate governance (or a lack thereof) in the context of global sustainable development – will remain of great relevance both intellectually and in practice.