The success of Franz Lehár’s Die lustige Witwe was not only sensational and widespread, it was unpredicted – the play on which it is based had, after all, been around for over forty years. When it was being prepared for its first performance in Vienna, the manager of the Theater an der Wien, Wilhelm Karczag, exhibited little faith in its prospects.Footnote 1 Its conquest of the stages of Europe and its appeal to the wider world was a possibility unforeseen. That is why it makes sense to name it as the foundation stone of the Silver Age of operetta. There may have been stage works of the time that had a longer continuous run in one country or another, but Die lustige Witwe had a cosmopolitan appeal that reached across borders. The most successful stage work in the UK in the first half of the twentieth century was Chu Chin Chow, but nowhere else in the world did it achieve anywhere near the same number of performances as did the West End production. In January 1908, London’s Daily Mail claimed that The Merry Widow had been performed 450 times in Vienna, 400 times in Berlin, 350 times in St Petersburg, 300 times in Copenhagen, and was currently playing every evening in Europe in nine languages. In the USA, five companies were presenting it, and ‘the rush for tickets at the New Amsterdam Theatre’ was likened to ‘the feverish crowding round the doors of a threatened bank’.Footnote 2 Stan Czech, in his Lehár biography, claims that by 1910 it had been performed ‘around 18,000 times in ten languages on 154 American, 142 German, and 135 British stages’.Footnote 3

After try-outs in several American cities, The Merry Widow opened at the New Amsterdam on Broadway on 21 October 1907, where its reception was seen by critics as an indication that audience standards were rising, an opinion that gave comfort to American operetta composers such as Reginald De Koven and Victor Herbert.Footnote 4 So well known did the operetta become that a burlesque version was produced in January 1908 at the Weber and Fields Music Hall, New York.Footnote 5 It used Lehár’s music, but had a new parodic script by George V. Hobart that cast Lulu Glaser as Fonia from Farsovia (rather than Sonia from Marsovia) and Joe Weber as the messenger Disch (instead of Nisch). Henry W. Savage, the manager of the New Amsterdam, granted permission for the parody, knowing that it would increase interest in his own production, which went on to enjoy a run of 416 performances.

Anyone studying the reception of German operettas in the UK and USA is bound to recognize that the productions in the West End and on Broadway of The Merry Widow marked a distinctive new phase in operetta reception.Footnote 6 Before The Merry Widow, the last German operetta to have a successful premiere in both London and New York was Carl Zeller’s Der Vogelhändler (produced first in Vienna in January 1891).Footnote 7 It became The Tyrolean at the Casino, New York, in October 1891, and was given five performances in German at Drury Lane, London, four years later.Footnote 8 Wiener Blut, an operetta of 1899 based on arrangements of the music of Johann Strauss Jr, was produced on Broadway as Vienna Life in early 1901, but had no outing in London.Footnote 9 A much-revised version of Hugo Felix’s Berlin operetta Madame Sherry enjoyed modest success in London in 1903, but did not reach New York until 1910, when Felix’s music was replaced by that of Karl Hoschna.

The librettists of Wiener Blut were Victor Léon and Leo Stein, and in 1905 they were to gain further acclaim with their adaptation of Henri Meilhac’s L’Attaché d’ambassade as Die lustige Witwe. In December that year, set to music by Franz Lehár, it opened at the Theater an der Wien, and in May the following year was at the Berliner Theater. The year after, it was produced as The Merry Widow at Daly’s Theatre in London’s West End and, a few months later, was on Broadway. The English version by Basil Hood and Adrian Ross was used in both London and New York. George Edwardes’s West End production opened on 8 June 1907 and ran for a remarkable 778 performances.Footnote 10 The actor-comedian George Graves, who played Baron Popoff in the operetta, looked back on the opening night in his autobiography of 1931, and declared: ‘Never have I known such wild enthusiasm as greeted this show.’Footnote 11 During and after the London run, The Merry Widow conquered the provinces, where it was performed at city theatres by the Edwardes touring companies and by what were known as ‘fit-up companies’ in Corn Exchanges, Town Halls, and other urban venues.Footnote 12

The massive success of The Merry Widow opened up a flourishing market for operettas from Vienna and Berlin. This was confirmed by the huge success of Straus’s The Chocolate Soldier in New York (1909) and London (1910). The stage works of Paul Lincke, who is credited as the founder of Berlin operetta with his one-act Die Spree-amazone of 1896, took time to travel. His ensemble song ‘Glühwürmchen’ from Lysistrata (1902) was familiar as an orchestral piece in London, and also featured in the Broadway show The Girl Behind the Counter (Talbot, 1907),Footnote 13 but his operetta Frau Luna (1899), popular in Germany, was not produced in London until 1911 (as Castles in the Air, at the Scala TheatreFootnote 14), and was not given at all in New York. In contrast, the Berlin operettas of Jean Gilbert were in demand in both London and New York. Other operettas – those of Victor Herbert excepted – were not doing well on Broadway following the success of The Merry Widow. Among the better, though unimpressive, statistics are: a run of 65 performances for Edward German’s Tom Jones at the Astor Theatre in late 1907, and 64 for Reginald De Koven’s Robin Hood at the New Amsterdam in 1912. John Philip Sousa’s The American Maid was given just 16 performances at the Broadway Theatre in 1913. Regular but short runs of Gilbert and Sullivan took place during 1910–13 at the Casino.

William Boosey comments that when he first went into publishing in the 1880s, French operetta was the dominant type, with Offenbach, Lecocq, Audran, and Planquette to the fore.Footnote 15 Operetta from the German stage ousted the French variety after 1907, although the latter returned during the First World War, with performances of Cuvillier and Messager. This needs to be qualified, however, because Cuvillier’s biggest success in the West End was The Lilac Domino (1918), which originally had a German libretto, and Messager’s Monsieur Beaucaire (London, April 1919, New York, December 1919) was composed to an English book by Frederick Lonsdale, with lyrics by Adrian Ross. Cuvillier’s French operetta, Afgar, was produced at the Pavilion, London in 1919, and the Central Theatre, New York, in 1920. A reason Paris was failing in the new operetta market was given by the American book and lyric writer Harry B. Smith, who remarked after a visit in 1909: ‘The revue was the only kind of musical piece in evidence.’Footnote 16 Nevertheless, the operettas of Henri Christiné, Maurice Yvain, and Reynaldo Hahn, proved successful in Paris, despite a puzzling lack of international interest in them.Footnote 17 The number of successful musical plays and operettas had, in fact, been declining in Paris after 1900. Between 1900 and 1914, 22.5 per cent of such pieces had runs of 100 performances or more in London, but only 5.7 per cent did so in Paris.Footnote 18

The Audience for Operetta

The disposable income of the middle and lower middle classes had increased in the late nineteenth century and changes in stage entertainment catered for the new audiences. Symptomatic of that was the renaming of music halls as Palaces of Variety, with its suggestion of greater respectability and suitability for a family audience. Linked to new audience appetites, also, was the development of romantic musical comedy as a substitute for burlesque in the 1890s. George Edwardes attributed his success, not to exceptional managerial and leadership skills, but to his understanding of an audience’s reactions.

I regard the members on an audience as the real critics. It is no use defying them as so many managers I know have done. That’s altogether wrong! It’s certainly very galling to spend many thousands of pounds upon a piece only to be rewarded with hisses; but when there is dissatisfaction my plan is carefully to examine the cause and see if there is really anything to complain about.Footnote 19

The West End and Broadway were both developing rapidly as centres of entertainment in the early twentieth century, helped by rising prosperity in the period before the First World War.

The audience attracted to operetta needs to be considered from two angles, the economic and the aesthetic – although nobody familiar with the work of Pierre Bourdieu will be persuaded that these two perspectives can be easily separated. In the West End, the aesthetic attraction of The Merry Widow lay in its melodious music, its new emphasis on glamour and romance, and in the charismatic performances of Elsie and Coyne, who became ‘idols of the day’.Footnote 20 The aristocracy did attend some of the theatres where operettas were staged, and evening dress was de rigeur for the stalls and dress circle, but these theatres attracted a cross-class audience, and the presence of aristocracy no doubt added to the allure of this genre. The presence of royalty at an opening night, as for The Count of Luxembourg in 1911, and the conducting of the opening night by the composer, further enhanced the glamour of the theatrical experience. Yet the presence of the King did not lend aristocratic status to operetta any more than it did to the Royal Variety Show, the first of which took place the following year. Commercial popular music was part of a ‘common musical culture’ in the first half of the twentieth century.Footnote 21 Another attraction of the theatre was spectacle, which relied on the latest technology (a discussion of this aspect of operetta will be found in Chapter 7).

Try-outs were common before West End or Broadway productions, so that changes could be made in response to the reactions of the first audiences. Manchester was a favourite try-out city in the UK, as was Boston in the USA for the entrepreneurial Shubert brothers. J. J. Shubert was, in fact, keen to turn the Boston Opera House into an operetta venue.Footnote 22 Tours to other cities took place with original cast members after the end of a West End or Broadway run, but other touring companies were sent out while a show was still running. Try-outs could be unreliable, for, as Phyllis Dare remarked, ‘very often that which appeals to London audiences falls quite flat in the provinces, and vice versa’.Footnote 23 An example is Jean Gilbert’s Lovely Lady (Die kleine Sünderin), which had a successful try-out at the Opera House, Manchester in early February 1932, but was a surprise flop at the Phoenix in London later that month. This is an example of transcultural reception on the small scale, the cultural transfer from one region to another, rather than one country to another. Basil Hood tended to adopt a nationalist tone when speaking of differences between Austrian and British audiences (see Chapter 5), but those differences are to a large extent merely another example of the same phenomenon.

Operettas successful in the modern city of Berlin were more likely to cross borders easily.Footnote 24 Vienna had a lingering taste for depictions of country manners. Lehár’s Rastelbinder was based on a Slovakian tale. Its folk-like style and its topic of Slovak immigrants in Vienna meant that, like Leo Fall’s Der fidele Bauer, it did not travel easily.Footnote 25 In October 1909, the latter enjoyed a short run as The Merry Peasant at the Strand Theatre in London, but was found ‘somewhat old fashioned according to the present lines of musical plays’.Footnote 26 In New York, it was performed for two weeks in German at the Garden Theatre. Although the First World War ruled out a production of Leon Jessel’s Schwarzwaldmädel, it, too, was unlikely to travel well. Like Der fidele Bauer, it was too firmly in the Volksoperette mould. The composer Edmund Eysler was a little too Viennese to export easily, though several productions of his operettas enjoyed modest success on Broadway, and one, The Blue Paradise (Ein Tag im Paradies), had a long run at the Casino in 1915.Footnote 27 His only operetta to be given productions in both London (1913) and New York (1914) was The Laughing Husband. It was, in fact, the only performance of an Eysler operetta in London. It may be that the lukewarm success of Oscar Straus’s A Waltz Dream in London and New York was a consequence of its being too Viennese.Footnote 28 It was at Hicks’s Theatre in 1908 (produced by Edwardes) but was thought to be miscast: ‘the whole cast did not seem to quite catch the right spirit’.Footnote 29 Its sad ending suited a Vienna that nursed nostalgic feelings for alt Wien, and it had been a huge success at the Carltheater in 1907, but it did not work in optimistic Edwardian London. Straus thought he was the first to introduce an operetta with a sad ending, but it was not novel in London, because Gilbert and Sullivan had already done so in Yeomen of the Guard (1888).

Sometimes, operettas did better in London and New York than in Vienna. Despite its mediocre reception at the Theater an der Wien in 1908, where it ran for just 62 performances, when Straus’s Der tapfere Soldat opened as The Chocolate Soldier at the Lyric, New York, in 1909, it ran for nine months. The Broadway version was soon taken to London and featured in the lead roles Constance Drever, who could both sing and act, and ex-Gilbert and Sullivan stalwart C. H. Workman. Drever’s singing of ‘My Hero’ was one of the highlights.Footnote 30 American Tin Pan Alley publisher Witmark and British publisher Feldman joined together to make money marketing this hit song. The West End triumph of The Chocolate Soldier encouraged Edwardes to revive A Waltz Dream at Daly’s in 1911, but its reception again proved disappointing.

Fall’s Die Dollarprinzessin achieved 428 consecutive London performances, compared to only 80 in Vienna, although it had enjoyed an initially enthusiastic reception there when it premiered at the Theater an der Wien in November 1908. No doubt that was because it featured the Austrian stars of Die lustige Witwe, Mizzi Günther and Louis Treumann. Karczag, who, in addition to being theatre’s director was also the Fall’s publisher, blamed Treumann for ruining the operetta’s success when he abandoned his role after two months.Footnote 31 It was produced to much greater success in Berlin in June 1908, and the Berliner Tageblatt commented on the marvels of its presentation.Footnote 32 It had to wait until September 1909 to be staged at Daly’s because of the success of The Merry Widow. The Broadway production by Charles Frohman was given almost simultaneously with that on the West End, but in a new English-language version by George Grossmith. Frohman then wanted to commission an all-American operetta from Fall, but Fall’s agent Ernest Mayer informed him that the composer would not know how to write an operetta specifically for America, when the whole world was open to him.Footnote 33 Fall’s response was symptomatic of the cosmopolitan outlook of those involved in operetta.

Sometimes an operetta differed in its Broadway and West End receptions. The Girl in the Train, Harry B. Smith’s version of Fall’s Die geschiedene Frau, was first given at the Globe Theatre, New York, in October 1910, and lasted for just 40 performances. Adrian Ross’s version of the same operetta (using the same title) opened at the Vaudeville Theatre, London, in June 1910, and ran for 339 performances. It would have continued, but Huntley Wright (playing the Judge) went to Switzerland for a holiday, and his understudy broke his arm.Footnote 34 Ralph Benatzky’s My Sister and I had only eight performances at the Shaftesbury Theatre, London, in 1931, but as Meet My Sister in New York it notched up 167. Jean Gilbert’s Die keusche Susanne was produced in London as The Girl in the Taxi (Lyric, 1912) and in New York as Modest Suzanne (Liberty, 1912). On Broadway, it managed just 24 performances,Footnote 35 but in London it ran for 384. With two successful West End revivals, it received a total of 597 performances during 1913–15, making it one of the most popular operettas in London. Why it fared so much better in London than New York is a question very difficult to answer, because a range of performance and staging factors need to be considered, as well as the content and its treatment.

Challenges to the Operetta Market

Operettas faced competition from other stage entertainment: at first, from musical comedies, and then, in the second decade of the century, from revues. These shows developed out of music hall and vaudeville, and consisted of turns and sketches related to a general theme. Hullo, Ragtime! (Hirsch), which opened at the Hippodrome on 23 December 1912, was the first of London’s ragtime-flavoured revues, and ran for 451 performances. Operettas from Berlin were already making significant inroads at this time, and not just those of Gilbert. Walter Kollo, who composed for the Berliner Theater during 1908–18, enjoyed an English production of his Filmzauber (co-composed with Sirmay, 1912) at the Gaiety, London, in 1913, given as The Girl on the Film. It lasted eight months in the West End, but only eight weeks on Broadway. The hugely successful Maytime at the Shubert, New York, in 1917 was based on Kollo’s Wie einst im Mai (1913), but it was changed almost out of recognition and given new music by Sigmund Romberg.Footnote 36

The first major blow to the operetta market, especially in the UK, was the outbreak of the First World War. Courtneidge had nothing ready for production in spring 1914, and Edwardes transferred to him his rights in Gilbert’s Die Kino-Königin. Courtneidge went to see it on Broadway, where it was being given as The Queen of the Movies, with book and lyrics by Glen MacDonough. He did not care for the adaptation, so he made his own, The Cinema Star, with assistance from Jack Hulbert.Footnote 37 The leading roles were played by his daughter Cicely and Jack Hulbert, who were later to marry. He soon found himself in a quandary over this production because of the disastrous turn of events brought on by war.

The play promised to be one of the most successful I had produced, and I looked forward with confidence to the future when the outbreak of War ruined all my hopes. The German origin of The Cinema Star was fatal. … After struggling vainly for a time I had to close the theatre.Footnote 38

Edwardes made a similar mistake: his purchase of the rights to produce Gilbert’s Puppchen also came to nothing because of the war. An even worse error was his neglect of his own safety abroad, resulting in his internment for some time at Nauheim, Germany, in 1914.

In the war years, a cosmopolitan appetite for operetta could be interpreted as unpatriotic. Although The Cinema Star was playing to full houses, it was withdrawn on 19 September 1914. That did not prevent it turning up with the original company at the Grand Theatre in Leeds the following year.Footnote 39 It was, in fact, Cicely Courtneidge who had suggested to her father that a tour would help recoup the losses caused by its premature closure in the capital. In her autobiography, she explains: ‘The fact that The Cinema Star was originally a German show was little known away from London and we played to very good business.’Footnote 40 A revival of Straus’s The Chocolate Soldier opened on 5 September 1914 at the Lyric Theatre, and ran for 56 performances, but the programme was careful to announce that service men in uniform could purchase half-price tickets, and profits were to go to the Belgian Relief Fund. Gilbert’s Mam’selle Tralala (Fräulein Trallala) had closed at the Lyric in July, but its music was revised by Melville Gideon, who then took all the credit when it reopened the following year as Oh, Be Careful! at the Garrick.Footnote 41 However, it lasted for only 33 performances, despite Yvonne Arnaud repeating her role as Noisette.

As the war continued, people felt uncomfortable about attending the theatre, and there were pressures on actors, too. Managers were asked to adopt a policy of only employing actors unfit for military service.Footnote 42 Nevertheless, two home-grown musical comedies of operetta-like character became enormous wartime hits: Frederic Norton’s Chu Chin Chow (His Majesty’s, 1916) and Harold Fraser-Simson’s The Maid of the Mountains (Daly’s, 1917). The latter was given 1352 performances, while Chu Chin Chow ran for an astounding 2238 performances (a record unbroken in the UK before Les Misérables). Remarkably, Emmerich Kálmán’s Soldier Boy! was first produced in London during wartime, in June 1918, but without his name on the programme. It was Rida Johnson Young’s 1916 Broadway adaptation (Her Soldier Boy) of Gold gab ich für Eisen, with revisions by Edgar Wallace. Acting as a distraction from the work’s origins, a song associated with the British troops, George and Felix Powell’s ‘Pack up Tour Troubles in Your Old Kit Bag’, was interpolated in both the New York and London productions.Footnote 43 The downside to Kálmán’s unique wartime achievement was that he received no royalties. However, barely two years after the war ended, he was to enjoy success with The Little Dutch Girl, which opened at the Lyric Theatre in December 1920.

Concern about productions of operetta from the German stage began to be voiced in New York after the USA entered the war in April 1917. At that time, two Kálmán operettas were running on Broadway, and, in June, Straus’s My Lady’s Glove (Die schöne Unbekannte) received its American premiere. In September 1917, The Riviera Girl, an adaptation of Kálmán’s Die Csárdásfürstin was to be seen on Broadway, and, in November, Lehár’s The Star Gazer (Der Sterngucker). The failure of the latter, which managed to scrape only eight performances, may be attributable to the changing public mood now that American troops were engaged in fighting. By May 1918, Rudolf Christians, the manager of Irving Place Theatre had been forced to cancel German-language performances because of public pressure, and a season of operetta in German to be produced by him at the Lexington Theatre, 1919–20, was also cancelled after heated debate.Footnote 44 Yorkville Theatre, a German-language theatre with a seating capacity of 1250, became an American playhouse in September 1918.Footnote 45 In August that year, it was announced that all royalties earned by ‘enemy holders of American rights to Broadway hits’ would be invested promptly in Liberty bonds.Footnote 46 When the war ended, the Shuberts planned to produce an American version of Eduard Künneke’s Das Dorf ohne Glocke, which had a nostalgic nineteenth-century setting and had been well received in Berlin in 1919, but their plans fell through.Footnote 47 As the reality of American deaths in the war sunk in, the appetite for German operetta evaporated.

Operettas dating from the war years were often neglected. Fall’s Die Rose von Stambul was a resounding success in Vienna in late 1916, and in Berlin the next year, but was not going to be welcomed as warmly in countries for which Germany, Austria, and Turkey (the location of the operetta) were the wartime enemy. There was no London production, and the Broadway production was not until 1922, when this work was growing in popularity in continental Europe. There were, of course, those who wanted a return to cosmopolitan entertainment in the West End once the war was over. Producer Albert de Courville asked in a letter to The Times on 8 April 1920, ‘Are we at liberty to reawaken public interest in a class of show highly delectable before the war?’Footnote 48

Operetta in the 1920s

After the war, many creators of operetta were eager to escape to the comfort of historical romances. Among the most popular operettas on historical themes were Madame Pompadour (1922), Die Perlen der Cleopatra (1923), Lady Hamilton (1926), Casanova (1928), Friederike (1928), Das Veilchen von Monmartre (1930) (with Delacroix and Hervé among the characters), Walzer aus Wien (1930), and Die Dubarry (1931). ‘Operetta makes history marketable’, scoffed Adorno: ‘it presents the demons of the past as casually as rag dolls, and despite our fears we play with them: they have no further power over us’.Footnote 49 Not all new operetta productions succumbed to nostalgia, however, and Berlin remained fond of the modern well into the final days of the Weimar Republic, as exemplified by Abraham’s Ball im Savoy, Dostal’s Clivia, and Straus’s Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will! The incorporation of African-American elements was also an embrace of the modern that brought an anachronism to historical costume drama. Kevin Clarke remarks on the simultaneous, if contrasting, development of jazz operetta and nostalgic operetta after the First World War.Footnote 50

Berlin became the centre for operetta production in the early 1920s, and British and American interest began to grow again. The market for musical comedy had waned, and the new American musicals of Gershwin and company were still to come. Most of the well-known operetta composers had turned to Berlin in the 1920s. Kálmán was the most resistant, remaining loyal to Vienna – his great success there being Gräfin Mariza (1924). Sometimes the British eagerness for German operetta outstripped the interest in Berlin: Jean Gilbert’s Die Frau im Hermelin (Theater des Westens, 1919), which became The Lady of the Rose (Daly’s, 1921), was greeted with ‘scenes of great enthusiasm’ by the London audience, and ran for longer than it did in Berlin.Footnote 51 It was a little less successful on Broadway, where it ran for 238 performances in all (beginning at the Ambassador in 1922 and transferring to the Century), but it was rare for any operetta to achieve 300 or more performances in New York (even The Chocolate Soldier made it to only 296). Gilbert visited New York in 1928, where he composed The Red Robe for the Shubert Theatre. Americans living in Berlin made it known back home if they saw a show that delighted them. The New York Times reported: ‘Enthusiastic Americans residents in Berlin early in 1921 frantically called the attention of American theatrical managers to “Der Vetter aus Dingsda,” a musical show playing at the Theater am Nollendorf Platz.’Footnote 52 This operetta by Eduard Künneke was bought by the Shubert brothers for production on Broadway as Caroline, and by Edward Laurillard for production in the West End as The Cousin from Nowhere.

Kálmán’s reception in London and New York could be unpredictable. Ein Herbstmanöver had a run of just 44 performances on Broadway as The Gay Hussars (1909) and 74 performances in the West End as Autumn Manoeuvres (1912). Die Csárdásfürstin, which had premiered at the Johann-Strauss-Theater in 1915 and went on to enjoy success at the Metropol, Berlin, also had a disappointing reception. It opened on Broadway in 1917 as The Riviera Girl, adapted by Guy Bolton and P. G. Wodehouse, with the setting changed to Monte Carlo, and incorporating additional numbers by Jerome Kern. The West End version, The Gipsy Princess, produced at the Prince of Wales Theatre in 1921, with a book by Arthur Miller and lyrics by Arthur Stanley,Footnote 53 was more successful than the Broadway version, and enjoyed a run of 212 performances. However, audiences failed to react with the enthusiasm of those in Austria and Germany, who regarded it as one of Kálmán’s finest achievements. Perhaps the recently ended war affected its British reception. The London Times referred to it, unusually, by the German term Operette, and, although conceding that much of the music was delightful, the review ended obliquely ‘one can only admire the courage of its producers in launching it at such a difficult moment’.Footnote 54 That may have referred to economic conditions, or to residual ill feeling towards Germany. In the next two years the appetite for German operetta began to grow again, but The Gipsy Princess had to wait for its London revival in 1981 to find itself fully appreciated.

Operetta and jazz-related dance music were vying for popularity in the 1920s, and the Shubert brothers were the major champions of the former. Blossom Time (Sigmund Romberg’s version of Heinrich Berté’s Das Dreimäderlhaus) was a huge hit for them in 1921, achieving a hundred more performances than had The Merry Widow for their business rival Abraham Erlanger. The Shuberts often visited Europe, and, while they always kept an eye open for novelty acts for their theatres, their main interest was in finding operettas that could be turned into Broadway successes.Footnote 55

Operetta and the Costs of Attendance

In the first three decades of the twentieth century, many people were prepared to pay for operetta, and an assortment of theatres and ticket prices enabled a broad social mixture to do so.Footnote 56 The London Hippodrome, which advertised itself as ‘the leading variety theatre’ put on a series of one-act operettas during 1909–12. Lehár’s Mitislaw, or The Love Match (Mitislaw der Moderne) was performed twice daily as part of a variety bill during November and December 1909, before being replaced by a Christmas spectacular The Arctic, complete with 70 polar bears.Footnote 57 More upmarket theatres, such as His Majesty’s, usually had tickets available for one shilling, the same price as a ‘posh’ seat in the stalls at a West End music hall but contrasting strongly with the cheapest seats at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden, which were two shillings and sixpence.

It needs to be borne in mind that in most theatres there were always fewer seats in the costliest parts of the auditorium. Even on an opening night at Daly’s there was a socially mixed audience, from the high society in the stalls to those in the pit and gallery who had queued all night because reserved seating was unavailable there.Footnote 58 MacQueen-Pope described the class mix of a Daly’s first-night audience:

The stalls were a living edition of Debrett. White waistcoats gleamed, women’s jewels shone and glittered – both sexes were perfectly ‘turned out’. The pit and the gallery had not forgotten how to applaud. The upper circle – that strange class-conscious part of the house – was packed with Suburbia. The dress circle held rich people and those who could not get into the stalls.Footnote 59

Those attending premieres were, in other ways, not typical. George Graves described them as ‘highly-specialized’, comprising guests of the management, people who attended out of social custom, critics of the press taking notes, and some ‘on the prowl’ who were ready to knock the show.Footnote 60 Commenting further on audiences, Graves declares that ‘pleasure-seeking suburbanites … roll up on Saturdays’, and are less critical than a mid-week audience.Footnote 61 At a Saturday matinée, however, spectators are ‘less noisy in their laughter and more sparing of applause’, which he attributes to the larger number of women present.Footnote 62 Nevertheless, despite this perceived reserve, he acknowledges the contribution made by women to the success of a show: ‘every actor knows, if you have the women with you the show is all right’.Footnote 63

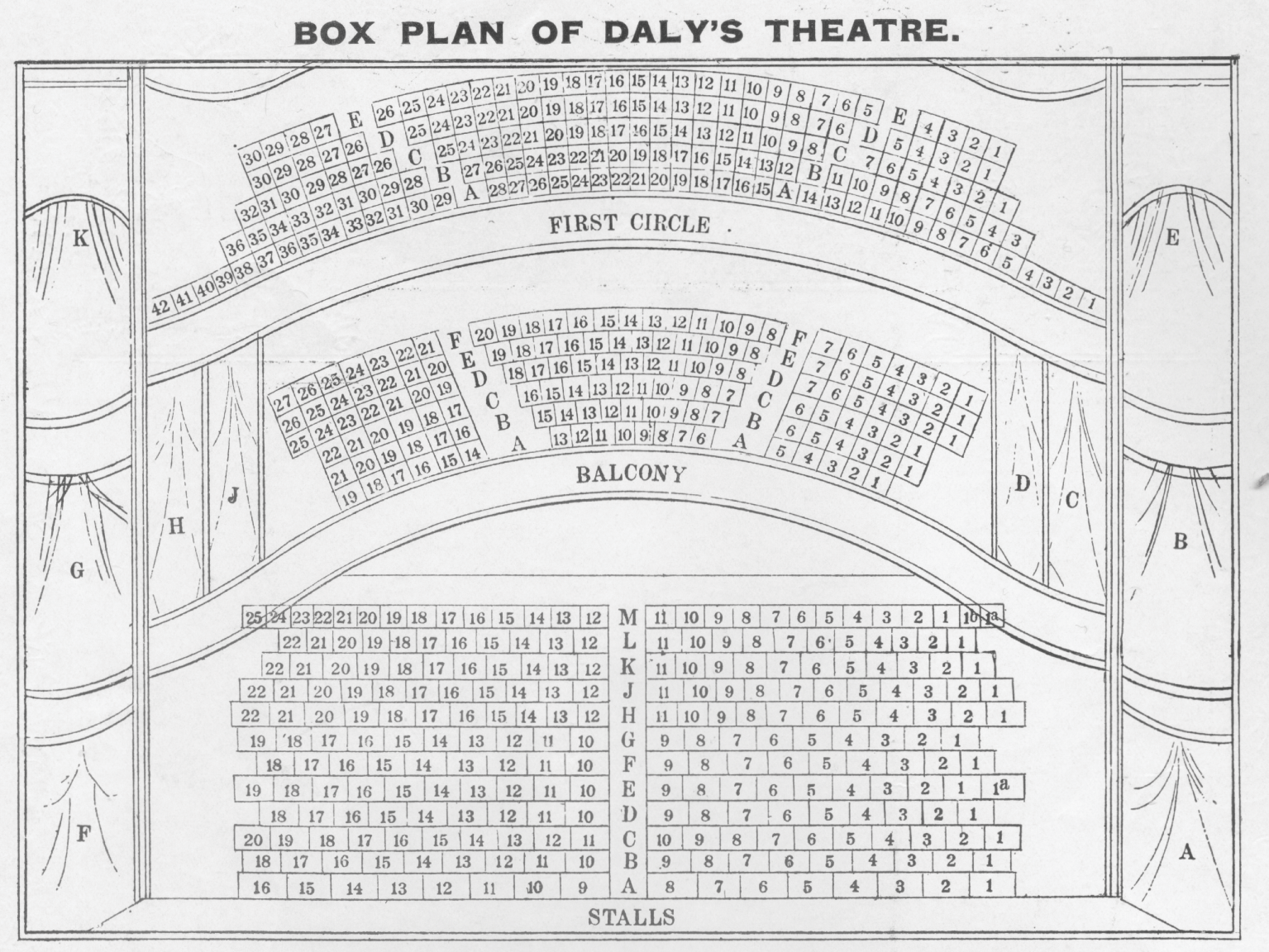

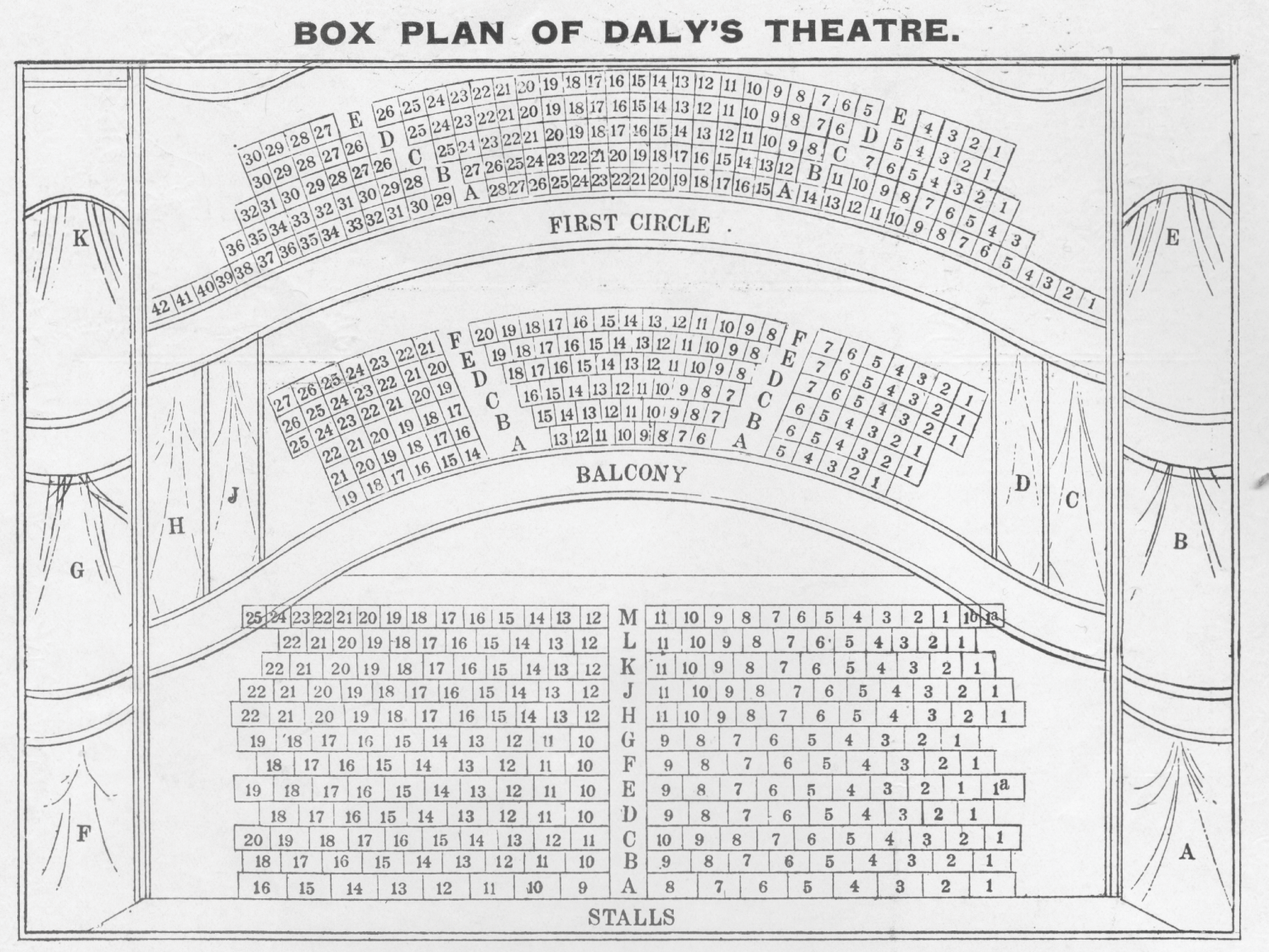

The price of private boxes (£2 12s. to £5 5s.), stalls (10s. 6d.) and circle (7s. 6d.) marked them out for the social elite, and the upper circle (4s. to 5s.) was for moneyed people whom MacQueen-Pope describes as ‘rather more flashy and less tasteful’.Footnote 64 His remarks indicate that money does not buy all the privileges of class – especially not ‘good taste’. The gallery and the pit – the latter located at the back of the stalls and under the balconies – were for the ‘general public’.Footnote 65 The pit was more expensive than the gallery: at Daly’s the prices were 2s. 6d. and 1s., respectively. On the box plan of Daly’s shown in Figure 5.1, the ‘balcony’ represents MacQueen-Pope’s ‘dress circle’, and the ‘first circle’ is his ‘upper circle’. Only half of the seating is shown: the gallery is not depicted, and the position of the pit is marked only by a straight line, that is because seats could not be reserved in either of those areas.

Figure 5.1 Box plan of Daly’s Theatre from the Play Pictorial, vol. 17, no. 103 (Mar. 1911). The pit (unreserved seating) is not shown but was behind the stalls.

A mixture of lower-middle and middle class made up the audience norm. A large portion of the audience were reasonably well off, as at other upmarket London theatres. His Majesty’s had similar prices to Daly’s. Before and during the First World War, most West End theatres offered a range of prices between 6d. to 10s. 6d. (children being generally admitted at half price). The Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, was a notable exception, with prices ranging from 2s. 6d. to 1 guinea. In the 1920s, some theatres attempted to raise prices, but this was met with many complaints. In April 1922, it was reported that the price of stalls at the Empire was to return to half-a-guinea [10s. 6d.], because the manager, Edward Laurillard, claimed he had received many letters ‘from music-lovers declaring that they could not afford to pay 12s. 6d.’Footnote 66

Operetta vs Musical Comedy

Continental European operetta entered a marketplace dominated by musical comedy. The latter was a genre that arose in the 1890s as people grew tired of absurd or satirical comic opera plots and looked for a mixture of humour and romance, and variety in musical style, from the operatic to music hall. Edwardes was a trendsetter with his shows at the Gaiety, such as The Shop Girl (Ivan Caryll) in 1894. British musical theatre retained much of that distinctiveness in later shows, such as Lionel Monckton and Howard Talbot’s The Arcadians (1909). Broadway was dominated in the early years of the twentieth century by British fare and by the operettas of Victor Herbert, although Jerome Kern, Rudolf Friml, and Sigmund Romberg soon appeared on the scene.

A New York Times critic remarked in 1910:

For years our ears have been so accustomed to the din of the mixed form [musical comedy] that the appeal of operetta failed to rouse us from our deafness. Importations from Vienna were made occasionally, but without much success. The red-wigged comedian, the overdressed showgirl, and the tinkling tunes were having their day, and nothing, it seemed, could stop them.Footnote 67

The desire for a male comedian in musical comedy related partly to the comedy roles in Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas, and partly to music hall and vaudeville, in which comedians were star ‘turns’. American musical comedy did not export well to London. Charles H. Hoyt’s A Trip to Chinatown, which ran for 657 performances at Madison Square, managed only 125 in London in 1894. However, in 1898, Gustave Kerker’s operetta The Belle of New York (book and lyrics by Hugh Morton) settled in at the Shaftesbury Theatre for a run of 693 performances. Its success proved Edwardes wrong in his assertion that ‘an American could not write a musical play that would succeed in England’.Footnote 68 It should be acknowledged that, although the librettist was American, the composer was German but had moved with his family to the USA at the age of ten, and all his theatrical experience was gained there.

Operettas were distinguished from variety theatre and musical comedy by being marketed as a more artistically serious form of musical play, even when the subject matter was comic. Operetta was not seen as an artistic compromise but, rather, as a genre that eschewed high art snobbery as much as it avoided low art vulgarism. The magazine Play Pictorial paid tribute to Kálmán’s The Little Dutch Girl by remarking that it was ‘abounding in lilting tunes and absolutely devoid of vulgarity’.Footnote 69 Theatre World praised Straus’s Cleopatra (1925) for containing ‘really witty lyrics’ and music that was ‘tuneful without being trite’.Footnote 70 Yet Oscar Asche’s exotic production did not draw in the 1920s audience as Chu Chin Chow had done in the previous decade.Footnote 71 In general, critics regarded operettas from continental Europe as superior to British and American musical comedy, and the battle of genres played itself out in many critical reviews. That said, the situation is complicated by the fact that, as Marion Linhardt has emphasized, genre identification was often a matter of promotion.Footnote 72 For instance, Gilbert’s Katja, the Dancer is designated ‘a musical play’ in the English vocal score – a term first used by Edwardes for Sidney Jones’s The Geisha (1896) to imply something akin to operetta. However, it was premiered in 1925 at the Gaiety as a ‘musical comedy’, no doubt because the audience there expected productions to have a more ‘piquant flavour’ than is suggested by the description ‘musical play’.Footnote 73 At first, it would seem that no such genre blurring would occur between operettas and revues, which were especially popular on Broadway, where some of them ran as a series with fresh material each year, for example, the Ziegfeld Follies (1907–31) and the Passing Shows produced by the Shuberts (1912–24). However, a mixed genre of Revue-Operette was to develop in Berlin in the late 1920s.

The Merry Widow was greeted by the New York Times as ‘the greatest kind of a relief from the American musical comedy’, and by The Times in London as a ‘genuine light opera … not overlaid (yet) by buffoonery’.Footnote 74 The insinuation was that it might soon acquire buffoonery to make it more appealing to the musical comedy audience. The urge to liven up an operetta with a comic routine was found in both cities. The Broadway production of Straus’s A Waltz Dream had an interpolated number in the second act that reminded one reviewer of ‘cheap American musical comedy’.Footnote 75 Occasional crude humour was not the only problem with musical comedy. What had helped it appeal initially was the absence of a complex or ludicrous plot, but this lack of attention to plot came to be seen as a lack of attention to dramatic structure. A London critic offers A Waltz Dream as an instructive model, ‘which the clever, but idle or, perhaps, hampered makers of English musical pieces might well take to heart’, because the music ‘is not dropped in here and there to relieve the tedium of a senseless plot’.Footnote 76

The conviction that musical comedy is beset by artificiality surfaces in a number of reviews. The Broadway production in 1922 of Gilbert’s The Lady in Ermine was welcomed as ‘genuinely musical and dramatic’, but irritated the reviewer in those spots ‘where it has been obviously touched up for what is conceived to be a popular taste for musical comedies which are neither musical nor comic’.Footnote 77 The notion that musical comedy fell below the artistic standards of operetta and did not require skilful performers is illustrated in a review of Künneke’s Love’s Awakening (Wenn Liebe erwacht) given in London in 1922: ‘The difference between Love’s Awakening and a musical comedy may be gauged from the fact that, whereas in the latter the songs seem to occur in an incongruous way, at the Empire last night it was the intermittent conversation that seemed incongruous.’ The critic sums up: ‘here was a real light opera with real music and performed with real ability by real singers’.Footnote 78 Love’s Awakening was an attempt to raise artistic standards at the Empire Theatre of Varieties by Edward Laurillard, its manager. His published announcement that, on the first night, he would present the piano score and book of lyrics to every member of the audience gives an idea of the cultural capital of those he expected to attend the production.Footnote 79 It was, indeed, considered an artistic success, but ran for only thirty-six performances.

When the next Künneke production, The Cousin from Nowhere (Der Vetter aus Dingsda), took place in London the following year, the Times critic noted that, although it was described as a ‘new musical comedy’, it had two peculiarities:

One is that it does not possess the conventional ‘chorus’ of men and women who fill the stage at frequent and unexpected moments in the usual production of this type. Secondly, although both the original ‘book’ and the music are by Continental writers and a Continental composer, in its present form it closely resembles English light opera.Footnote 80

Conferring the label ‘light opera’ on a stage work always implied its superiority over musical comedy. Findon, of the Play Pictorial, was very taken with it and felt that no music ‘of more bewitching tunefulness’ had been composed since the days of Sullivan.Footnote 81 He praised its stars, Walter Williams (the stranger), Helen Gilliland (Julia), and Cicely Debenham (Wilhelmine), and he remarked on its enthusiastic audience reception. Although it contained no choruses, it included complicated ensemble work, as in the Act 2 finale. After a run of more than a hundred performances in London, Laurillard announced his intention to send out two touring companies.Footnote 82 A sign of the changing times, however, is that Walter Williams did not join the tour but, instead, accepted a part in the jazzy revue Brighter London (Finck) featuring Paul Whiteman and his orchestra at the Hippodrome.

A reviewer of the Broadway adaptation of Künneke’s operetta as Caroline (1923) informs readers that American theatrical managers, having been alerted to the enthusiastic reception given to Der Vetter aus Dingsda in Berlin, had gone to see what the fuss was about:

the managers came, one by one, and delivered their verdict: ‘A great show, but impossible for America. The singing cast it calls for would ruin any production financially.’ But finally there came a bolder one, and it was as a result of his visit that the Shuberts last night presented ‘Caroline’ at the Ambassador.Footnote 83

At the end of the decade, however, there was evidence of a growing concern that operetta composers, who had become swept up in a fashion for historical themes, were becoming too earnest. In 1930, a London reviewer of Lehár’s Frederica (Friederike) is unconvinced by this operetta based on the early life of Goethe. He argues that the composer’s artistic ambitiousness ‘has led to nothing more than pretentiousness’, and adds, significantly, ‘it is only in one or two lighter numbers written for the soubrette that the music sounds happy and at ease’.Footnote 84 The accusation of pretentiousness is always promptly made when popular genres dare to exhibit artistic aspirations. It is a criticism more usually directed at musical entertainment than plays; for example, a play of 1923 by Clemence Dane about incidents in the early life of Shakespeare gave rise to no similar concerns.Footnote 85 Taunts about excessive artistic pretensions are found in the previous century in Hanslick’s criticism of Strauss Jr’s concert waltzes and, in the later twentieth century, they surfaced in the critical reception of ‘progressive rock’. In Germany, some critics were offended at the idea of Goethe appearing in an operetta. Others objected to the Jewish writer Fritz Löhner-Beda adapting Goethe’s poetry.Footnote 86 After 1933, his efforts would be viewed as not simply adapting Goethe, but as falsifying or Judaizing Goethe – a literary equivalent to the Schubert adaptations by Jewish composer Heinrich Berté (real name, Bettelheim) in Das Dreimäderlhaus, described in a Nazi publication of 1940 as an ‘unscrupulous plunder and falsification of the works and form of one of the greatest German masters’.Footnote 87

Not every composer was travelling along the same aspirational artistic path as Lehár. Erik Charell established what he called ‘revue operetta’ with a trilogy of stage works he directed in Berlin: Casanova, 1928, Die drei Musketiere, 1929, and Im weißen Rössl, 1930. Retitled White Horse Inn, the latter enjoyed great success in London and New York and has been discussed in previous chapters. Countering the gripes of critics who thought revue operetta was all about adding a Schlager (a hit song) here and there to a musical play, Charell declared that the isolated number was not the decisive factor in revue; instead, ‘the constantly glittering movement of the whole’ was needed to keep an audience excited.Footnote 88 However, in 1932, when Benatzky’s Casanova (with music from Johann Strauss, Jr) was produced at the Coliseum, a critic reproached it for being ‘as thin a story as has ever dragged a musical comedy across Europe’.Footnote 89 This is not to suggest that it was rare for the plots of operettas to be criticized. Within half-a-dozen years of the triumph of The Merry Widow, British and American critics were beginning to complain about the many plots involving ‘petty Courts and showy uniforms’, or ‘tottering principalities, the elimination of which would probably prove fatal to the librettist’s inspiration’.Footnote 90

Moral Questions Raised by Operetta

In addition to critical-aesthetic reception, theatrical productions were open to moral concerns. Motivated, perhaps, by the renown bestowed on Maxim’s restaurant by The Merry Widow, an attempt was made to mount a London production of Georges Feydeau’s comic play La Dame de chez Maxim of 1899. In 1912, it was one of seven plays banned that year by the Lord Chamberlain’s Office (another was Strindberg’s Miss Julie, dismissed as ‘a clever but revolting play’).Footnote 91 The Lord Chamberlain’s Office, to which all plays (musical and spoken) had to be submitted, had the power to reject them or demand alterations before granting a licence for performance. La Dame de chez Maxim, which had a storyline about a respectable man who becomes involved with a coquette, was described as ‘A French farce of a decidedly “polisson” type throughout. A great success in Paris, but unsuited for a London audience.’Footnote 92 The play was much admired later; indeed, George Grossmith Jr refers to The Girl from Maxim’s as ‘an oft-played comedy’ in his autobiography of 1933, and Alexander Korda directed a British film of it that same year.Footnote 93 The fact that a licence had been granted for The Merry Widow does not mean that it was not found morally objectionable by some. The author Arnold Bennett expresses his distaste in his journal entry for 23 February 1910:

All about drinking, and whoring and money. All popular operetta airs. Simply nothing else in the play at all, save references to patriotism. Names of tarts on the lips of characters all the time. Dances lascivious …Footnote 94

In March 1912, there was a debate on censorship in the House of Lords,Footnote 95 but that same month a petition was submitted ‘from West End Theatre Managers to the King’, asking for no change in the licensing of theatre plays.Footnote 96 Among the signatories were George Edwardes (Daly’s, Gaiety, and Adelphi Theatres), P. Michael Faraday (Lyric Theatre), Arthur Collins (Drury Lane), Robert Courtneidge (Shaftesbury Theatre), and R. D’Oyly Carte (Savoy Theatre).

The Lord Chamberlain’s Office felt a need to clarify its position regarding ‘doubtful plays’, and explained that they fell into two types:

1) ‘general tone or plot is objectionable’, examples being gross immorality, obscenity, or ‘risk of international complication’;

2) ‘the language is indecent, blasphemous, or contains offensive personal allusions’.Footnote 97

Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession was cited as an example of the first type; it had been rejected for its plot: ‘Mrs Warren kept a Brothel’. Many were left dissatisfied by such reasons for suppression, and, in July 1912, another petition was presented, but this time in opposition to the Lord Chamberlain. The next year, Robert Harcourt, in a parliamentary debate on 16 April, introduced a bill proposing the abolition of the censorship of plays. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office continued to function, however, until 1968, and the first stage production that followed its demise was the hippie rock musical Hair (book and lyrics by James Rado and Jerome Ragni, music by Galt MacDermot).

A sample of comments from the Lord Chamberlain’s Office (LCO) will illustrate some of the deliberations made before granting a licence in return for a fee of forty-two shillings. Fall’s The Girl in the Train deals humorously with a court case for divorce, a serious and sensitive matter at this time, but it elicited no negative comments from the LCO, and that may be because the play on which it was based, Victorien Sardou’s Divorçons!, had already received a licence for performance in a translation by Margaret Mayo in June 1907. Some changes had been made: the play was set in New York, the operetta version was set in Amsterdam; but, more to the point, the content of the German libretto by Victor Léon had been toned down by Adrian Ross (the Vienna version is discussed in Chapter 7). It was given a licence on 13 June 1910; unusually, this came a week after its first performance at the Vaudeville Theatre.

Gilbert’s The Girl in the Taxi has a leading character, Suzanne Pomarel, who has won a prize for conjugal virtue, a quality she distinctly lacks. Some of its eroticism may seem tepid today:

Suzanne: ‘Oh, dear, my shoe has come untied’.

Hubert: ‘By Jove, what ripping ankles’.

The subject matter was found a little indecent by the LCO, but prompted a jaded response: ‘its chief scenes [are] laid in a gay Parisian restaurant, whither there come, as usual, for supper various improper husbands unaccompanied by their proper wives’. Paris always conjured up a morally unwholesome environment for the respectable British middle class. A licence was granted, however, on 23 August 1912, a week before the first performance at the Lyric Theatre.Footnote 98

The same weary, reproachful tone is detected in the LCO’s comments on The Girl on the Film (music by Albert Sirmay and Walter Kollo), licensed on 4 April 1913, the day before its first performance at the Gaiety Theatre: ‘The underplot affords opportunity for the flirtations of the young ladies, who, whether as typists or followers of Terpsichore, are always looked for, and at, in Gaiety entertainments.’Footnote 99 Another operetta on the subject of film making, Gilbert’s The Cinema Star, is summed up as follows: ‘Its plot is chiefly concerned with the adventures of one Clutterbuck, a millionaire who has been prompted by his wife to agitate for the suppression of the cinematograph shows, and how he was trapped into being “filmed” in a compromising position.’Footnote 100 That is putting it mildly, given that he was tricked into appearing in a film called Count Porn’s Last Adventure, in a scene that creates the impression of an attempted rape. The official, however, ignores this and decides, instead, that some of the lyrics require specific comment. He reports that ‘the searcher for evil’ might interpret the lines ‘in the shade of the street, every girl that we meet is a maid who was just made for love’ as a reference to ‘street-walkers’, although he believes that would be foolishly mistaken.Footnote 101 A licence was granted on 3 June 1914, the day before its premiere at the Shaftesbury. The libretto offers some insight into contemporary moral anxieties about cinema-going. In Act 3, a police constable invites a woman into the cinema, and she exclaims in response:

Wot me – with you! In a place where they turn the lights out? You stop your nonsense! You’re exceeding the speed limit, you are.

A certain degree of suspicion is aroused by The Joy-Ride Lady, an adaptation by Arthur Anderson and Hartley Carrick of another of Gilbert’s operettas, Das Autoliebchen. The term ‘joy-rider’ was new in 1914,Footnote 102 and the Parisian setting would immediately raise moral suspicion. Moral concern would be reinforced by lyrics such as the following, from the chorus in the Act 1 Finale:

The LCO believed, however, that there was more of an intention to suggest naughtiness than to make it explicit:

I think the intention of the Play is to attract people by the report that it is improper, and I have no doubt that the original was extremely so. As it stands, however, it is not, so far as the situations and dialogue go, worse than many plays of the kind.Footnote 103

It was granted a licence on 19 February 1914, a few days ahead of its production at the New Theatre.

A production suspected of being morally improper was not necessarily good for business. ‘Immorality is not a popular card to play in middle-class England’, wrote Findon, commenting on propriety and the stage in 1921.Footnote 104 Even a title could arouse suspicion. He relates that one regular playgoer informed him that she could on no account go to see a play called Hanky Panky John, despite assurances that it was devoid of offence.Footnote 105 That was a good enough reason to change an operetta title like Die geschiedene Frau into The Girl in the Train.

The acceptable duration of an embrace or kiss on stage was not specified. The scene in which Robert Evett (as Lieutenant Niki) kissed Gertie Millar (as Franzi) in the first London production of A Waltz Dream (1908) became known as, and was even advertised as, ‘the longest kiss on record’.Footnote 106 When Edwardes revived this operetta in 1911, he decided against repeating the extended kiss, perhaps because it might seem a publicity stunt rather than because of moral objections. Yet, even in the more liberal 1920s, Jimmy White, who had taken over as manager of Daly’s, worried about the close embrace in the last act of Straus’s Cleopatra between the heroine and Mark Antony. His anxiety abated after the producer Oscar Asche assured him that the couple’s marriage had been ratified by the Egyptian priesthood.Footnote 107

After the First World War, the London Public Morality Council, a quasi-official municipal body, became fretful about sex and the stage. The Council published a booklet titled Sex Plays and Books, reproducing excerpts from publications from 13 to 20 February 1925, and quoting a writer in the Daily News who stated: ‘In America, I am told, a certain play is openly advertised a “sexy”.’Footnote 108 The operations of the Censor of Plays became an issue again in March 1926, when the Daily Telegraph reported that means were being found to evade the law, including the production of unlicensed plays in theatres on Sunday evenings.Footnote 109 Another debate on the Censorship of Plays took place in the House of Lords on 10 June 1926.Footnote 110

In New York, where no censorship office existed, some reviews contain expressions of distaste similar to those found in London. A reviewer of the Broadway production of The Lilac Domino deplored its vulgar humour: ‘Jokes about sausages, hot dogs, and other comedy of the burlesque stage are plentiful, if not pleasing.’Footnote 111 A ‘threat of flaunting licentiousness’ was found to be arising in the 1924–25 season, which led to calls for a stage censor.Footnote 112 There being none, the District Attorney stepped in, but, in the end, took no legal action. The next season, however, a court case was brought against William Francis Dugan’s play The Virgin Man, and Mae West was fined and spent ten days in the workhouse as a consequence of her production Sex. In the wake of this intervention by the District Attorney, the following season, 1927–28, witnessed the arrival of what was called the ‘Wales padlock law’, which meant that a theatre presenting a questionable play could be closed for a year, and its producers and performers brought to trial.Footnote 113

Politics and issues of gender and sexuality are discussed further in Chapter 7, but suffice it to say, here, that operetta was rarely thought a political threat. Even a piece as strongly oriented politically as Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s Die Dreigroschenoper (1928) was given a New York production (as The 3-Penny Opera) at the Empire Theatre in April 1933, in a version by Clifford Cochran and Jerrold Krimsky. The New York run was only 12 performances, but Marc Blitztein’s version for the off-Broadway Theatre de Lys enjoyed a record-breaking run of 2500 performances. It was that version which came to the Royal Court Theatre in February 1956, with Sam Wannamaker as stage director and Berthold Goldschmidt as musical director. Brecht and Weill’s Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (1930) was not performed in the West End until 1963, nor given an off-Broadway production until 1970, but its German reception had not proved encouraging to theatre managers elsewhere. There was a riot at the Leipzig premiere, and, at the Frankfurt performance, an audience fight that resulted in someone being shot dead. In this stage work, Brecht painted a relentless political satire of capitalism: Mahagonny is a fictional city, supposedly in Alabama, where everything is tolerated except lack of money.

The Waning Enthusiasm for Operetta Post-1933

The decline in productions on Broadway and in the West End of operetta from the German stage can be linked to several factors. One was the persecution of Jewish creative artists and the Nazi state control of operetta, which is discussed in the postlude to this book. Another was the growing enthusiasm for the new Broadway musicals and for sound film and screen musicals. There were also other leisure-time pursuits to distract the erstwhile operetta lover: social dancing and dance bands, for instance, and radio and records. Radio ownership was increasing in the mid-1920s, but records were still expensive. However, prices fell in the 1930s and records joined sound films as channels for the dissemination and promotion of American music. As syncopated American popular styles established a position of dominance in that decade, much of the music of operetta was beginning to sound like a bygone era.

The new jazzy Broadway musical had begun to have an impact in the West End during 1925–28, with shows by George Gershwin, Jerome Kern, and Vincent Youmans. The novel character of the latter’s No, No, Nanette! was recognized by The Theatre World in July 1925:

‘No, No, Nanette’ may be said to have been the first of the new type of musical comedy, which is rapidly ousting the more old-fashioned ‘waltz and kiss’ style of musical play. … High spirits are the secrets of the success of these modern shows … Quick-fire dancing and quick-fire comedy are the order of the day.Footnote 114

No, No, Nanette! opened in March 1925 at the Palace Theatre and ran for 665 performances. In contrast, Lehár’s Frasquita opened in April and closed after 36 performances. In June, as if responding to competition, the next Lehár production in the West End was Clo-Clo, which was described by a disgruntled critic in Theatre World as ‘a jazz maniacal comedy’.Footnote 115 It did continue for a respectable run of 95 performances, but Oscar Straus’s ‘old-fashioned’ Cleopatra, also produced in June, was still running when Clo-Clo closed. It was not, therefore, only the American jazzy style of show that appealed to West End audiences, and, in fact, the three biggest successes imported from the USA to the London stage in the second half of the1920s were of a more traditional operetta character: Rudolf Friml’s Rose-Marie and The Vagabond King, and Sigmund Romberg’s The Desert Song. Operetta from the German stage also remained a strong force: Gilbert’s Katja, the Dancer was hailed in 1925 as ‘one of the biggest successes the Gaiety has ever known’ – the reviewer adding, somewhat backhandedly, ‘even the waltz songs are not as irritatingly cloying as usual’.Footnote 116 It transferred to Daly’s in September 1925 and enjoyed, in all, a run of 514 performances, which puts it in third place (behind Rose-Marie, with 851 performances, and No, No, Nanette!) among the most successful shows opening that year. Even in 1933, the Daily Telegraph welcomed Straus’s Mother of Pearl at the Gaiety as ‘a great relief from the blatant jazz compositions from which we have so long suffered’.Footnote 117

At the same time as Broadway was exporting energetic fun mixed with romance, some operettas were taking a melancholy turn. In late 1929, the New York Times claimed that Berlin impresarios the Rotter brothers knew the value of offering a piece that gave the audience the opportunity ‘for a good cry’.Footnote 118 The work the newspaper had in mind was Lehár’s Friederike, which was to arrive eventually at the Imperial Theatre in 1937. The sad ending and theme of resignation had already been present in Ein Walzertraum and Das Dreimäderlhaus.

Broadway musicals increased their presence on the London stage in the 1930s. Singer-comedian George Graves was more anxious about the ‘American invasion’ of the West End than he was about continental European fare, because American stage works were not adapted in the same way, and thus they threatened ‘to eclipse our language and social standards’.Footnote 119 By 1931, the year Graves published his autobiography, he sensed the danger from Broadway has passed, and prophesized that ‘a renewal of the popularity of British shows’ would follow the ‘long spell of foreign domination of our theatre’.Footnote 120 He failed to see that the Broadway shows had prepared the ground for the later dominance of American musicals in London. When Lehár’s Paganini was produced by C. B. Cochran at the Lyceum in 1937, it had Richard Tauber and Evelyn Laye in the lead roles, and contained some Lehár’s most lyrical music; yet, even so, the reception was disappointing. It was beginning to seem as if continental European operetta’s glory days were over.

A weariness with operetta after the Second World War is evident in the Times review of the revival of Stolz’s Wild Violets (Wenn die kleinen Veilchen blühen) at the Stoll Theatre, London, in February 1950. The reviewer thinks it ‘may be of interest to the younger generation as a period piece’, but Annie Get Your Gun (Berlin) and Oklahoma! (Rodgers and Hammerstein) had arrived in the West End three years before and had ‘led audiences to expect a whole string of catchy tunes’.Footnote 121 Wild Violets actually continued for a respectable run of 121 performances, but it had achieved 290 at Drury Lane during 1932–33. It is ironic that the up-to-date George Gershwin told Oscar Straus, with whom he had become friends during the latter’s American visits, that The Chocolate Soldier was his favourite musical.Footnote 122 Gershwin did not dismiss Straus as old fashioned, even if his own stage works now epitomized contemporary musical theatre. Nevertheless, Straus was present at the opening night of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! in 1943 and remarked afterwards: ‘Something new and elemental has arrived. It is a revolution which makes old fogeys like me seem academic, perhaps even classical.’Footnote 123 Straus’s Three Waltzes (Die drei Wälzer) was the last silver-age operetta to have a Broadway premiere in the 1930s. It opened at the Majestic Theatre, 25 Dec. 1937 and ran for 122 performances. After that, there was no premiere of an operetta from the German stage until 1946, when the long-planned production of Lehár’s Das Land des Lächelns finally opened at the Shubert Theatre with the title Yours Is My Heart. It lasted a mere 36 performances, despite the presence of Richard Tauber.