Book contents

- French Gothic Ivories

- French Gothic Ivories

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on the Text

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Ivory in the Gothic Emporium

- 2 Thrones of Wisdom

- 3 “Fleshly Tablets of the Heart”

- 4 Glorification of the Virgin

- 5 Contemplation and Desire

- 6 An Ivory Enterprise

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 September 2022

- French Gothic Ivories

- French Gothic Ivories

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on the Text

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Ivory in the Gothic Emporium

- 2 Thrones of Wisdom

- 3 “Fleshly Tablets of the Heart”

- 4 Glorification of the Virgin

- 5 Contemplation and Desire

- 6 An Ivory Enterprise

- Epilogue

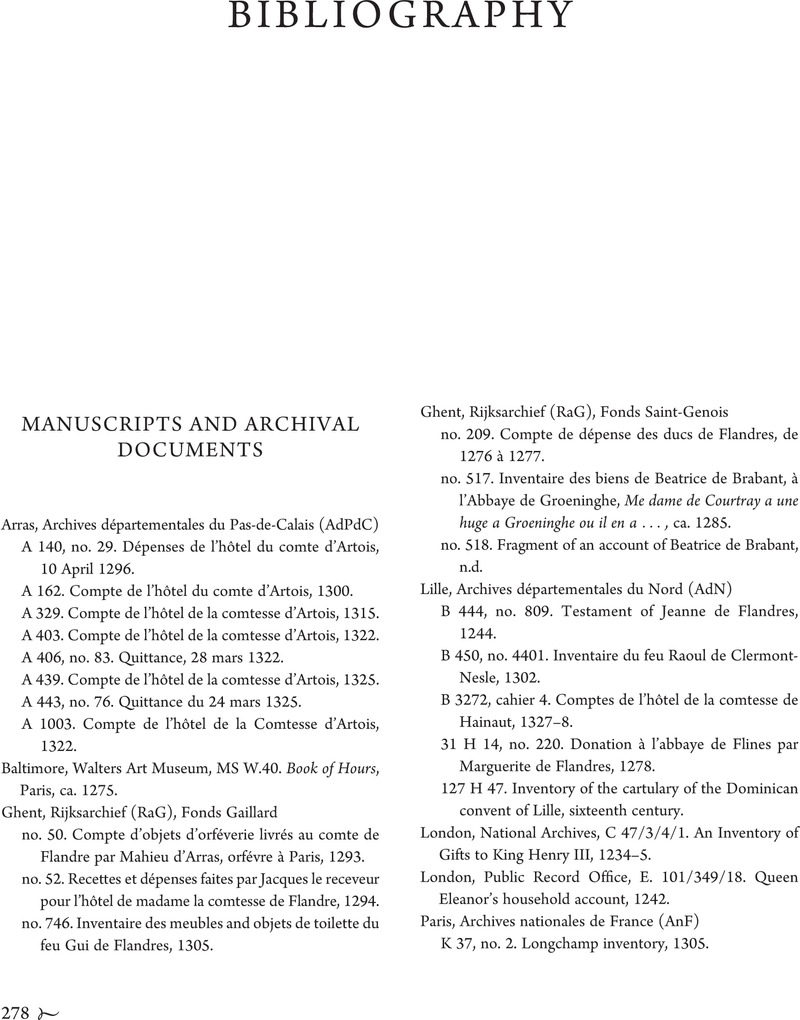

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- French Gothic IvoriesMaterial Theologies and the Sculptor’s Craft, pp. 278 - 307Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022