Several themes unite the wide-ranging chapters in Part VI as the authors explore what lessons can be learned from the disparate ways in which governments around the globe responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. First, there is a complicated relationship between democratic institutions and a nation’s ability to respond to serious disease outbreaks. Reasonable people might hypothesize that democracy is a handicap during public health emergencies. Authoritarian governments can get even draconian things done quickly, quashing public resistance. Further, the more the law dilutes power in order to impose checks and balances and prevent abuse, the more it hobbles a swift response. But, on the other hand, democratic institutions make it harder for government to deny or downplay public health threats without detection, and federalism and other forms of power decentralization make it possible for some units of government to mount a vigorous pandemic response, even if others refuse.

In Chapter 22, “COVID-19 and National Public Health Regimes: Whither the Post-Washington Consensus in Public Health?,” Tess Wise, Gali Katznelson, Carmel Shachar, and Andrea Louise Campbell empirically investigate how effectively countries with different political, legal, social, cultural, economic, and organizational structures stemmed the early spread of COVID-19. The authors report the surprising finding that the countries whose systems appeared best prepared for a public health emergency enjoyed no clear advantage. Neither development nor democracy significantly predicted governmental effectiveness in fighting disease spread.

In Chapter 23, “A Functionalist Approach to Analyzing Legal Responses to COVID-19 Across Countries: Comparative Insights from Two Global Symposia,” Joelle Grogan and Alicia Ely Yamin also consider the connections between democratic institutions and governmental performance during health emergencies – specifically, a nation’s performance in protecting human rights. Drawing on findings from two multi-country symposia, they conclude that formal legal regimes (for example, whether a country uses emergency-powers laws or ordinary legal powers) may be less important to whether a country avoids abuses of power during a pandemic than the social and political environment in which these regimes function. Grogan and Yamin voice greater suspicion about undemocratic regimes than Wise and her coauthors, perhaps because their conception of an effective government response includes consideration of human rights concerns.

In Chapter 24, “A Tale of Two Crises: COVID-19, Climate Change, and Crisis Response,” Daniel Farber worries about democratic nations’ ability to solve global crises when their governments are fractured and polarized. He considers the connections between the two seminal global crises of our age: COVID-19 and climate change. Farber’s analysis finds that although the pandemic induced short-term reductions in carbon emissions, its longer-term impacts on how societies obtain and use energy are more uncertain. He notes opportunities to pursue a “green recovery,” using economic stimulus funds to invest in clean energy, but also the prospect of long-term damage to public transportation infrastructure. Farber trenchantly observes that while both crises have generated fervent hopes for technological rescues, making technology effective in combating the crises requires complex social investments.

In Chapter 25, “Vaccine Tourism, Federalism, Nationalism,” Glenn Cohen highlights the complexities that federalism layers on already thorny problems such as vaccine allocation. Democratic institutions, he underscores, can be both friend and foe during health emergencies. Cohen asks who, among several different groups of community outsiders, may have a morally legitimate claim to a community’s vaccine doses, and why. Fixing on communitarian principles as a lodestar, he offers a helpful definition of who belongs to a community for the purpose of vaccines.

A second theme connecting the chapters pertains to measurement. Answering questions about the optimal form of governance during pandemics begs the question: Optimal for what? Which outcomes are most relevant to assess? For instance, should we focus on COVID-19 cases and deaths, as Wise and colleagues do, or a more holistic assessment of how countries balance disease response with individual rights protections and equity considerations, per Cohen and Grogan and Yamin? Further, how can we rigorously conduct cross-national comparisons when countries differ in so many ways?

The ambitious empirical analysis undertaken by Wise and her coauthors illustrates the challenges. Countries have different levels of baseline vulnerability to infectious disease spread due to features unrelated to their legal, political, and social structures – for example, different levels of rurality and population mobility, and entry into the pandemic at different times, when different levels of knowledge had accumulated about how SARS-CoV-2 spreads. Figuring out how to rigorously isolate effects and control for confounding factors will occupy analysts of COVID-19 governance for some time.

For now, we can reach only tentative conclusions about how much political, legal, and public health systems matter to effective pandemic response. It is valuable to make the point, as Wise and her coauthors do, that prepositioning is not destiny when it comes to fighting novel pathogens. But some caution is warranted before concluding that redressing historical underinvestment in public health and health care systems will not help next time. On the contrary, Grogan and Yamin argue, it is reasonable to continue to operate on the assumption that having a well-functioning health care system and a public health system that assures equitable access to preventive and therapeutic measures will help avoid loss of life. Similarly, Cohen’s chapter gives rise to the inference that investing in advance planning for pandemic countermeasure allocation will yield dividends.

A final thread uniting the chapters is the notion of community. For many reasons and in many respects, COVID-19 led to the rapid drawing of lines around communities throughout the world. From the allocation of vaccine doses to the imposition of community mitigation orders, national, state, and local communities asserted themselves in defining their own individual pandemic responses. While this patchwork created interesting natural experiments to study, as the chapter by Wise and her coauthors shows, it likely undermined an effective global response to the virus. Whereas other global crises – most notably, World War II – cultivated social solidarity and a widening of the concepts of community and belonging, COVID-19 drove social fragmentation. Not only did this complicate disease response (for example, by prompting vaccine tourism and perpetuating inequities in COVID-19 outcomes among population subgroups), it may also have enervated the prospects for global cooperation to solve other problems, such as climate change. Our joint future may depend on redefining community. To the searching questions that Grogan and Yamin ask at their chapter’s end – “who should exercise power, of what sort, and over whom?” – might be added, “who should exercise care, of what sort, and for whom?”

Collectively, these chapters shed much light on the critical question of what constitutes good governance during a pandemic and how it can be secured for populations around the world.

I Introduction

On June 2, 2016, the Center for Strategic and International Studies Global Health Policy Center in Washington, DC hosted a conversation with Jim Yong Kim, then president of the World Bank Group. Kim’s talk was entitled “Preventing the Next Pandemic.” Framed by the Ebola crisis that was just winding down in West Africa, pandemics in 2016 were presented as primarily a problem for developing countries. In his introductory remarks, the Center for Strategic and International Studies moderator, J. Stephen Morrison, even felt it necessary to remind the audience that understanding pandemics “mattered” for “US national interests.”Footnote 2 The primary pandemic-prevention mechanism proposed by the World Bank was emergency pandemic financing and insurance. In his remarks, however, Jim Yong Kim also argued that health was central to more than just national well-being: it was a key driver of economic growth and development. He cited findings from the Lancet Commission Report that, between 2000 and 2011, about 24 percent of income growth in developing countries resulted from improvements in health.Footnote 3

Kim’s position reflected what is sometimes called the “Post-Washington Consensus,” or the conclusion that development strategies should emphasize a broad array of social policies beyond what had been originally emphasized by the “Washington Consensus” of the 1980s and 1990s. The originator of the Washington Consensus, John Williamson, suggested that public expenditure priorities be redirected toward “neglected fields” such as “primary health and education, and infrastructure.”Footnote 4 Nevertheless, scholars generally agree that the Washington Consensus was characterized by a dominant orthodoxy that countries should “stabilize, privatize, and liberalize.”Footnote 5 When the Post-Washington Consensus was proposed in the mid-2000s, health again emerged as an area scholars saw as key for development,Footnote 6 though, as evidenced by Kim’s suggestions regarding pandemic insurance and financing, market-forward solutions are still seen as central, reflecting an international trend toward leveraging financial markets for development that some have dubbed the “Wall Street Consensus.”Footnote 7

Health will undoubtedly be central to any emerging global development consensus, but as the COVID-19 pandemic has made clear, a broader global consensus on public health, including the vision of society informing the concept of “the public,” is needed. In this chapter, we use data from the World Bank and other (Post-)Washington Consensus institutions to create a snapshot of global public health on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic. We find that (Post-)Washington Consensus institutions saw the world as having varying levels of public-health-related development and social priorities. We then examine how countries from different clusters in this space fared in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (in other words, before vaccinations became available in at least a few countries). We find that the countries supposedly best prepared for a public health emergency had no systematic advantage and even lagged behind countries that were supposedly not as well prepared in the early stages of the pandemic. Similarly, other classifications of public health preparedness from the pre-COVID-19 period, such as the World Health Organization’s Joint External Evaluation Tool or the Global Health Security Index, which did not adequately predict detection time and mortality in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, also fell short.Footnote 8 From our data and case studies, we are concerned that a tradeoff between democracy and government effectiveness may be a lesson taken from experiences in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and suggest instead that a social democratic perspective on public health that links justice and efficacy is needed.

II Creating a Typology of Public Health Regimes

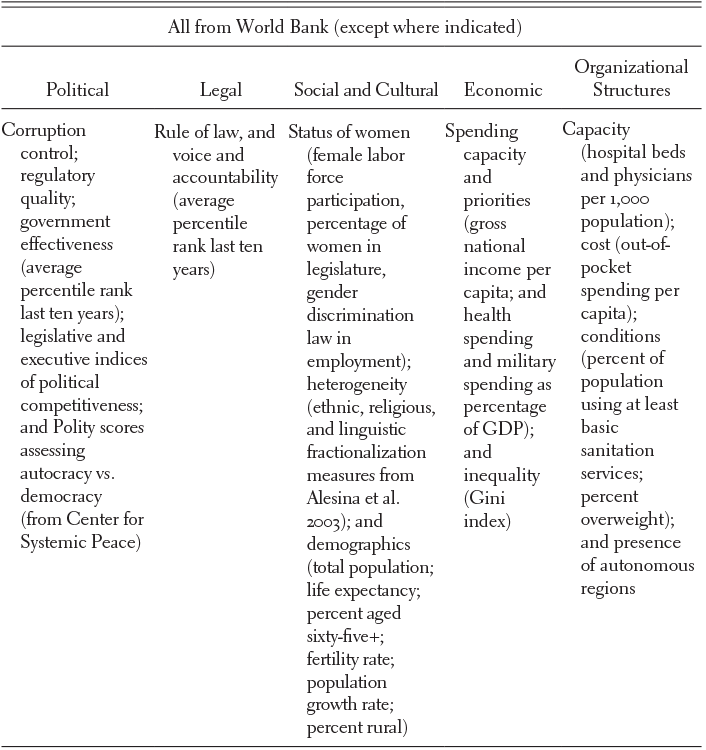

To create a typology of public health regimes that characterizes the variation in national public health on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of institutions such as the World Bank, we group countries by similarity in “political, legal, social, cultural, economic, and organizational structures” related to public health.Footnote 9 While Asthana and Halliday emphasize that scholars can tailor public health regimes to study particular areas, such as nutritional inequalities or anti-smoking campaigns, we look broadly to see whether grouping countries by general indicators of public health can help us understand performance in response to the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our indicators of public health-related factors come primarily from World Bank and United Nations data, with two additional indicators of democracy, using the 2018 POLITY5 scores,Footnote 10 and ethnic and linguistic fractionalization, from measures developed by Alesina et al. in 2003.Footnote 11 Table 22.1 below shows the full set of indicators.

Table 22.1 Global indicators of public health

| All from World Bank (except where indicated) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political | Legal | Social and Cultural | Economic | Organizational Structures |

| Corruption control; regulatory quality; government effectiveness (average percentile rank last ten years); legislative and executive indices of political competitiveness; and Polity scores assessing autocracy vs. democracy (from Center for Systemic Peace) | Rule of law, and voice and accountability (average percentile rank last ten years) | Status of women (female labor force participation, percentage of women in legislature, gender discrimination law in employment); heterogeneity (ethnic, religious, and linguistic fractionalization measures from Alesina et al. 2003); and demographics (total population; life expectancy; percent aged sixty-five+; fertility rate; population growth rate; percent rural) | Spending capacity and priorities (gross national income per capita; and health spending and military spending as percentage of GDP); and inequality (Gini index) | Capacity (hospital beds and physicians per 1,000 population); cost (out-of-pocket spending per capita); conditions (percent of population using at least basic sanitation services; percent overweight); and presence of autonomous regions |

When conducting a global analysis, choices of indicators are limited to what is widely available and reliably measured. This limits what we can choose to explore and has theoretical implications because existing data do not come into existence by chance. Our analysis relies primarily on World Bank data, which, we argue, are indicators of a weak “Post-Washington Consensus” in public health.

These indicators arise from a contested paradigm. The Washington Consensus of the 1980s and 1990s on effective development strategies was associated with Washington-based policy institutions with strong international influence – such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the US Treasury – which were proponents of neoliberal development policy.Footnote 12 Before the mid-2000s, when a spate of studies called its effectiveness into question, the Washington Consensus represented the dominant ideology in the area of development.Footnote 13 Though there have been numerous efforts to move beyond the Washington Consensus, such as the Post-Washington Consensus, no new dominant ideology has taken hold.Footnote 14 As Joseph E. Stiglitz put it in 2008, “If there is a consensus today about what strategies are most likely to promote the development of the poorest countries in the world, it is this: there is no consensus except that the Washington Consensus did not provide the answer.”Footnote 15 Despite being a contested consensus, the (Post-)Washington Consensus still looms large in contemporary indicators such as those we draw upon in this chapter, understandings of concepts such as “governance,” and global targets such as the Sustainable Development Goals.Footnote 16

A Principal Component Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a statistical method used to project high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving as much variation as possible. The “principal components” uncovered by PCA are linear combinations of the indicators that define orthogonal axes of variation. Running PCA on our 116-country dataset reveals two main components (see the Methodological Appendix in this chapter for the methodological details). Figure 22.1 shows how countries map onto them.

Figure 22.1 PCA results

1 A Primary Component of “Development”

Countries’ scores on the primary component, accounting for 40.9 percent of the overall variance, are graphed along the x-axis in Figure 22.1. We interpret these scores as broad indicators of public health-related development in the context of a weak Post-Washington Consensus.

The primary component distinguishes between, on the one hand, nations with good governance, high levels of health infrastructure, a more elderly and urban population, higher income levels, and longer life expectancy, and, on the other hand, nations with lower indicators of good governance, lower levels of health infrastructure, a younger and more rural population, lower income levels, and shorter life expectancy. We describe this component in more detail in the Methodological Appendix.

2 A Secondary Component of “Social Priorities”

The second component, explaining 10.4 percent of the variation in the data, is characterized by political distinctions that, in linear combination, explain variation orthogonal to (independent of) the first component. Countries’ scores on the second component are graphed on the y-axis of Figure 22.1. We describe the secondary component as a measure of “social priorities” related to public health. The social priorities component is characterized by women’s position in society, military spending, and democracy. Countries that score low on social priorities, and cluster at the center bottom of Figure 22.1, have lower levels of women in the workforce, higher military spending, and lower levels of democracy compared to countries with higher scores. Again, we describe this component in more detail in the Methodological Appendix.

B K-Means Clustering to Identify Public Health Regimes

We apply a second statistical method, k-means clustering, to group the countries based on their similarities within our statistical space to define groups that we call public health regimes.

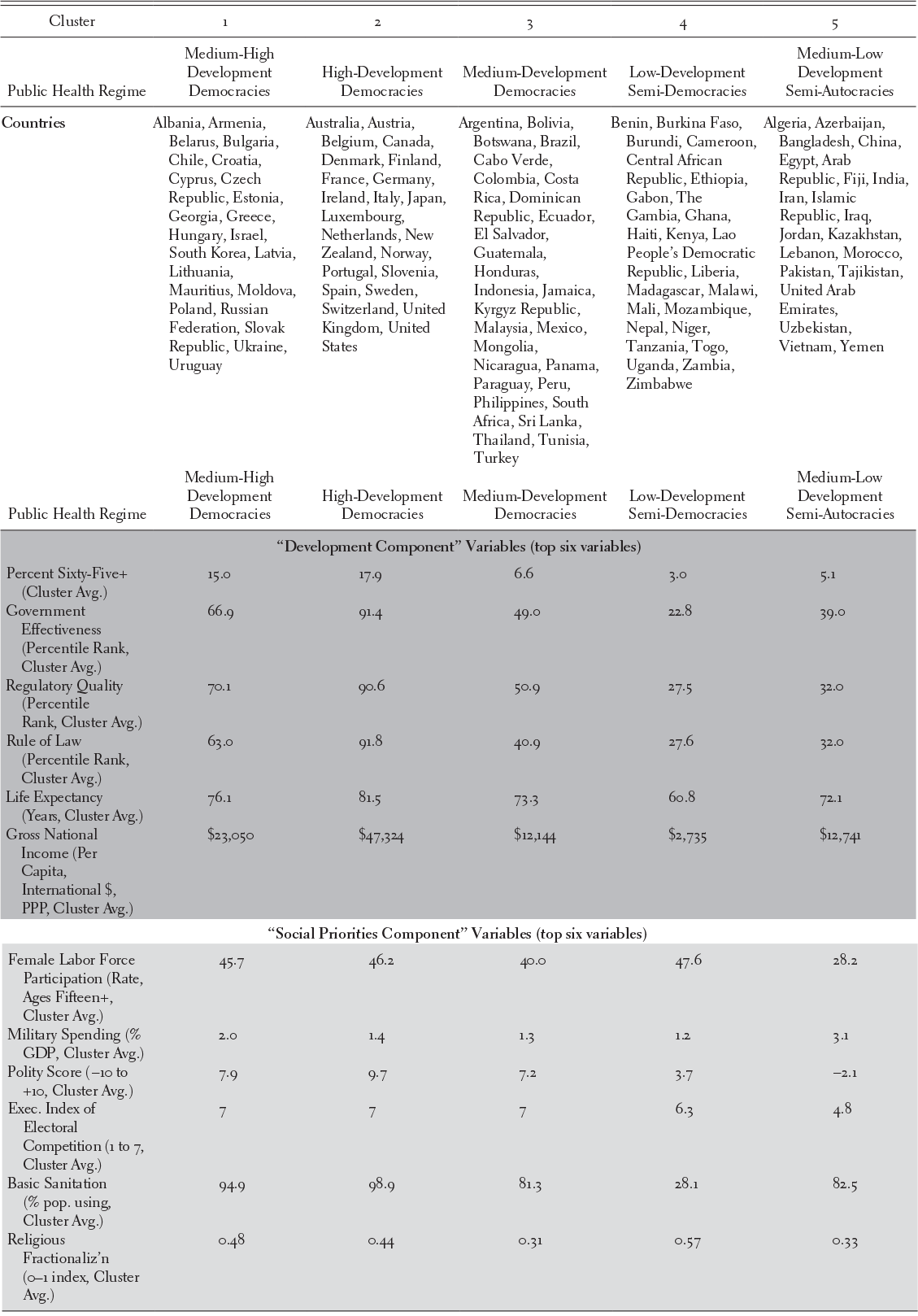

Theoretical motivation, certain statistical indicators, and face validity suggest that five clusters are optimal (see the Methodological Appendix). Figure 22.2 shows our clusters graphed over the first two components from the PCA. Table 22.2 summarizes the public health regimes that we find using five-cluster k-means.

Table 22.2 Public health regimes and key characteristics

| Cluster | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Health Regime | Medium-High Development Democracies | High-Development Democracies | Medium-Development Democracies | Low-Development Semi-Democracies | Medium-Low Development Semi-Autocracies |

| Countries | Albania, Armenia, Belarus, Bulgaria, Chile, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Israel, South Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Mauritius, Moldova, Poland, Russian Federation, Slovak Republic, Ukraine, Uruguay | Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States | Argentina, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Cabo Verde, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Indonesia, Jamaica, Kyrgyz Republic, Malaysia, Mexico, Mongolia, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey | Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Haiti, Kenya, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Nepal, Niger, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe | Algeria, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Arab Republic, Fiji, India, Iran, Islamic Republic, Iraq, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, Tajikistan, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, Yemen |

| “Development Component” Variables (top six variables) | |||||

| Percent Sixty-Five+ (Cluster Avg.) | 15.0 | 17.9 | 6.6 | 3.0 | 5.1 |

| Government Effectiveness (Percentile Rank, Cluster Avg.) | 66.9 | 91.4 | 49.0 | 22.8 | 39.0 |

| Regulatory Quality (Percentile Rank, Cluster Avg.) | 70.1 | 90.6 | 50.9 | 27.5 | 32.0 |

| Rule of Law (Percentile Rank, Cluster Avg.) | 63.0 | 91.8 | 40.9 | 27.6 | 32.0 |

| Life Expectancy (Years, Cluster Avg.) | 76.1 | 81.5 | 73.3 | 60.8 | 72.1 |

| Gross National Income (Per Capita, International $, PPP, Cluster Avg.) | $23,050 | $47,324 | $12,144 | $2,735 | $12,741 |

| “Social Priorities Component” Variables (top six variables) | |||||

| Female Labor Force Participation (Rate, Ages Fifteen+, Cluster Avg.) | 45.7 | 46.2 | 40.0 | 47.6 | 28.2 |

| Military Spending (% GDP, Cluster Avg.) | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 3.1 |

| Polity Score (−10 to +10, Cluster Avg.) | 7.9 | 9.7 | 7.2 | 3.7 | −2.1 |

| Exec. Index of Electoral Competition (1 to 7, Cluster Avg.) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6.3 | 4.8 |

| Basic Sanitation (% pop. using, Cluster Avg.) | 94.9 | 98.9 | 81.3 | 28.1 | 82.5 |

| Religious Fractionaliz’n (0–1 index, Cluster Avg.) | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.57 | 0.33 |

Figure 22.2 Five clusters – our selected grouping

III How Have Different Public Health Regimes Fared in the Context of COVID-19

We now examine how different public health regimes fared in the COVID-19 pandemic. We draw on data from the University of Oxford’s COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT),Footnote 17 for government response outcomes, and from Johns Hopkins University, for cases and deaths.Footnote 18 These datasets, while the most comprehensive data available at the time of writing, are not infallible. For example, in low- and middle-income countries, even during non-pandemic times, most deaths occur outside of the hospital system and are unlikely to have a cause-of-death certified by a physician.Footnote 19 Noh and Danuser find that in half of the fifty countries they explored, actual cumulative COVID-19 cases were estimated to be five to twenty times greater than the confirmed cases.Footnote 20

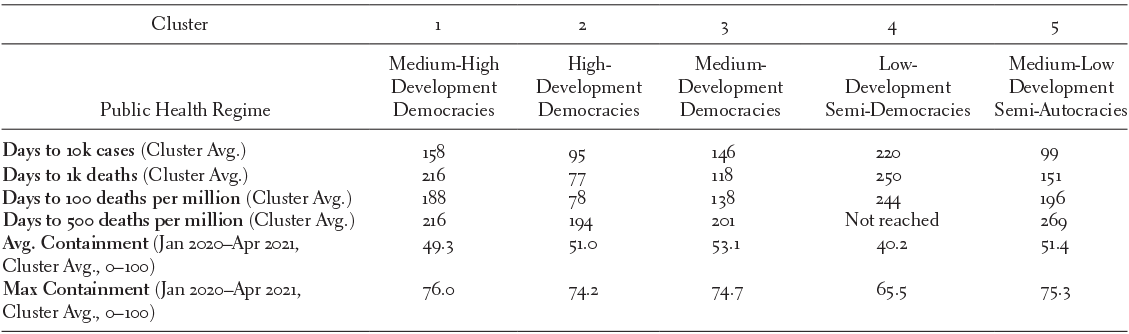

The first set of outcomes we examine is how fast COVID-19 spread and how comprehensive the government response was. We might expect a comprehensive response to slow the spread and variation in response and speed to vary across public health regimes we established in the previous section. Interestingly, neither pattern is borne out in the data.

In Figure 22.3, the x-axis indicates the number of days between the first and the 10,000th reported case in each country. The y-axis displays the maximum government containment score (0 to 100) over the period from January 1, 2020, and April 10, 2021, the maximum data window allowed at the time of analysis.Footnote 21 Maximum government containment comes from OxCGRT and includes the sum of fourteen indices from the areas of containment and closure policies (e.g., closing schools) and health system policies (e.g., public information campaigns) scaled to vary between 0 and 100. Taking a government’s maximum score on this metric produces a somewhat blunt measure of the initial COVID-19 response, but one that reflects the broad contours of important variation in government responses. In the Methodological Appendix, we show an alternative measure using the average government containment, which does not change the substantive results. The shape of the marker indicates the country’s cluster (public health regime).

Figure 22.3 Max government containment vs. speed of spread

Figure 22.3 and Table 22.3 indicate that none of the public health regimes we identified had a distinct advantage against COVID-19 in slowing the spread during the early phases of the pandemic. The High-Development Democracies (Cluster 2), which we would expect to be the best prepared, actually had the fastest spread, with only 95 days on average to reach 10,000 cases and 77 days on average to reach 1,000 deaths. While we might attribute the seemingly outstanding performance of the Low-Development Semi-Democracies (Cluster 4) to poor data quality, the fact that the High-Development Democracies did worse than Medium- and Medium-High-Development Democracies (Clusters 1 and 3), and even worse than Medium-Low-Development Semi-Autocracies (Cluster 5), is harder to attribute to data quality issues. This pattern persists even after accounting for population and examining the number of days to reach 100, then 500, deaths per million. Levels of containment were similar across all public health regimes, except for Low-Development Semi-Democracies (Cluster 4), which had somewhat lower average and maximum containment than other public health regimes.

Table 22.3 Public health regimes, speed of spread, government response

| Cluster | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Health Regime | Medium-High Development Democracies | High- Development Democracies | Medium- Development Democracies | Low- Development Semi-Democracies | Medium-Low Development Semi-Autocracies |

| Days to 10k cases (Cluster Avg.) | 158 | 95 | 146 | 220 | 99 |

| Days to 1k deaths (Cluster Avg.) | 216 | 77 | 118 | 250 | 151 |

| Days to 100 deaths per million (Cluster Avg.) | 188 | 78 | 138 | 244 | 196 |

| Days to 500 deaths per million (Cluster Avg.) | 216 | 194 | 201 | Not reached | 269 |

| Avg. Containment (Jan 2020–Apr 2021, Cluster Avg., 0 –100) | 49.3 | 51.0 | 53.1 | 40.2 | 51.4 |

| Max Containment (Jan 2020–Apr 2021, Cluster Avg., 0 –100) | 76.0 | 74.2 | 74.7 | 65.5 | 75.3 |

In sum, the High-Development Democracies of Cluster 2, those we expect would be best prepared, were likely to see a faster spread than countries with any other public health regime.

We might attribute some of this rapid spread to location, data quality, and demographics. However, examples from across the world highlight that these factors alone were not enough to determine a country’s destiny. For example, in Figure 22.3, Thailand stands out as a country that managed to slow the spread significantly despite geographical proximity to, and a close trade relationship with, China.

Figure 22.4 examines another factor that may have increased the challenge of containing COVID-19: the percentage of a country’s population aged sixty-five and older. For this analysis, we examine the number of days it took to reach the threshold of ten deaths per million. We see a negative relationship – countries with younger populations took somewhat longer to reach ten deaths per million – but there are some notable outliers, particularly South Korea, which has an older population, but was one of the slowest to reach the ten deaths per million threshold (260 days).

Figure 22.4 Percent sixty-five plus vs. days to reach 10 COVID-19 deaths per million population

In general, there is no strong correlation between what we identify as a country’s prior public health regime and its performance in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. If anything, countries we might have expected to perform the best, those with the most consolidated democracies and higher levels of governance, income, and state capacity (the high-development democracies of Cluster 2), did worse in slowing the spread and lowering the death rate than countries in other clusters. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, the weak (Post-)Washington Consensus in public health is not indicative of less devastation even among its best students, just as the (Post-)Washington Consensus did little to stop the Great Recession of 2007–2009 from affecting wealthy countries around the globe.Footnote 22 Explaining this underperformance will take further analysis, but contributing factors may be demographics (as Cluster 2 countries tend to be older) and difficulty implementing non-pharmaceutical social interventions. We now conduct brief case studies to produce suggestions for key factors that we should be incorporating into our understanding of good public health.

IV Case Studies

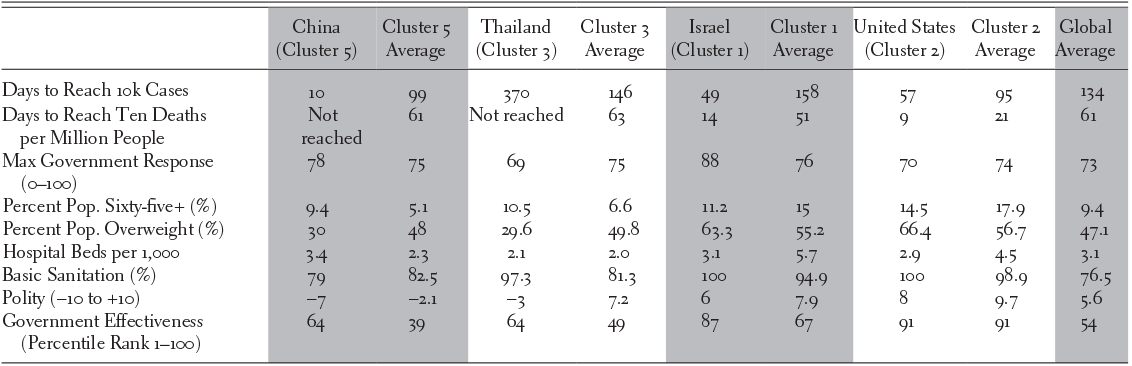

We chose to investigate China, Thailand, and Israel through brief case studies. China is unique on a global scale because of its large population and experience of coping with an emerging virus first. China is a Cluster 5 country (medium-low development semi-autocracy). Thailand is a Cluster 3 country (medium-development democracy), though it bucks the dominant trend of its group by being an autocracy with a Polity score of -3. Finally, Israel is a Cluster 1 country (medium-high-development democracy).Footnote 23 Table 22.4 shows comparative pandemic outcomes and selected background characteristics for each country relative to its cluster. The performances of these countries stand out in comparison to the poor performance of the United States and the other high-development countries of Cluster 2.

Table 22.4 China, Thailand, Israel, and United States pandemic outcomes

| China (Cluster 5) | Cluster 5 Average | Thailand (Cluster 3) | Cluster 3 Average | Israel (Cluster 1) | Cluster 1 Average | United States (Cluster 2) | Cluster 2 Average | Global Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days to Reach 10k Cases | 10 | 99 | 370 | 146 | 49 | 158 | 57 | 95 | 134 |

| Days to Reach Ten Deaths per Million People | Not reached | 61 | Not reached | 63 | 14 | 51 | 9 | 21 | 61 |

| Max Government Response (0–100) | 78 | 75 | 69 | 75 | 88 | 76 | 70 | 74 | 73 |

| Percent Pop. Sixty-five+ (%) | 9.4 | 5.1 | 10.5 | 6.6 | 11.2 | 15 | 14.5 | 17.9 | 9.4 |

| Percent Pop. Overweight (%) | 30 | 48 | 29.6 | 49.8 | 63.3 | 55.2 | 66.4 | 56.7 | 47.1 |

| Hospital Beds per 1,000 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 5.7 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 3.1 |

| Basic Sanitation (%) | 79 | 82.5 | 97.3 | 81.3 | 100 | 94.9 | 100 | 98.9 | 76.5 |

| Polity (−10 to +10) | −7 | −2.1 | −3 | 7.2 | 6 | 7.9 | 8 | 9.7 | 5.6 |

| Government Effectiveness (Percentile Rank 1–100) | 64 | 39 | 64 | 49 | 87 | 67 | 91 | 91 | 54 |

A China

China, where the novel coronavirus originated, experienced rapid spread to 10,000 cases, but quickly controlled the disease, ultimately performing better than the rich democracies of Cluster 2. The effective Chinese response was facilitated by public health and industrial capacity, and by governmental and cultural factors.

After the first cases were reported in Wuhan in December 2019, lockdowns, school closures, and transport suspensions quickly followed. Coordination among government offices, extensive testing, and a national system of contact tracing facilitated the response, as did the early use of Fangcang hospitals to isolate mild-to-moderate cases from both homes and conventional hospitals. Although China has a large elderly population, only 3 percent live in nursing homes, minimizing one major source of infection experienced in some Western countries. Testing and quarantine measures for travelers aimed at preventing imported cases. China’s status as the world’s largest manufacturer of personal protective equipment also facilitated its reaction.Footnote 24

Among the public, “fresh memories” of the SARS-CoV outbreak hastened the response, as did ready compliance with mask wearing.Footnote 25 In general, the pandemic countermeasures were less fettered by concerns with civil liberties. “In China, you have a population that takes respiratory infections seriously and is willing to adopt non-pharmaceutical interventions, with a government that can put bigger constraints on individual freedoms than would be considered acceptable in most Western countries,” noted Gregory Poland, director of the Vaccine Research Group at the Mayo Clinic, adding that the response in the United States has been hampered by “hyper-individualism” and a “raucous anti-vaccine, anti-science movement that is trying to derail the fight against COVID-19.”Footnote 26 At the same time, the pace of vaccination was relatively slow because the country’s inactive-virus-based vaccine candidates took longer to manufacture, because millions of doses were donated to other nations to bolster foreign relations, and because, ironically, the effective response undercut urgency among the population, in contrast to the United States and United Kingdom, where raging infection rates spurred desperation over getting vaccinated.Footnote 27

B Thailand

Thailand illustrates the phenomenon of good governance without democracy, and its success in containing the pandemic is likely to reinforce calls for an emphasis on governance over democracy in the emerging public health consensus.Footnote 28

In March 2019, Thailand held elections for the first time since 2014, when a military coup overthrew its democratically elected government. Unfortunately, the 2019 election was widely considered to have been designed to prolong and legitimize the military’s dominant role in Thailand’s governance.Footnote 29 Between 1996 and 2018, Thailand’s ranking on the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators fell. Between 2002 and 2018, Thailand’s global rank decreased from the 65th percentile to below the 20th percentile for political stability, and from the 60th percentile to the 20th percentile for voice and accountability. However, government effectiveness remained relatively stable (around the 65th percentile). Kantamaturapoj et al. report that public services remain functioning with adequate quality, “reflecting a degree of independence from political pressure and a capacity to formulate and implement policies among bureaucrats.”Footnote 30

Since 2002, Thailand has provided comprehensive health benefits to its entire population through a universal coverage scheme with a high level of financial risk protection, as well as voice and accountability provided through legislative provisions and a deliberative process.Footnote 31 This health system was put to the test when, on January 13, 2020, Thailand was the first country to detect a case of COVID-19 outside of China.Footnote 32 After an initial spike in cases, Thailand went 102 days between May and September without any reported local transmission of COVID-19.Footnote 33

Thailand’s public health response to COVID-19 was swift and comprehensive. The Thai government quickly recommended the use of face masks and this was met with 95 percent compliance from the Thai population.Footnote 34 Tracing and quarantining were set up by rapid response teams, who isolated cases in facilities rather than in homes. When demand for N95 face masks spiked amid a global shortage, a new factory was constructed in a month, supplying free N95 masks to health facilities.Footnote 35 By the end of July 2020, a laboratory network for diagnosing COVID-19 using PCR (polymerase chain reaction) tests was active in 78 percent of Thailand’s seventy-seven provinces.Footnote 36

Although Thailand was successful in the initial stages of its response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Marome and Shaw raise concerns over the Thai government’s handling of the social and economic fallout from declining tourism revenue.Footnote 37

C Israel

Israel is one of the medium-high-development democracies that showed moderate success at COVID-19 containment during the initial months of the pandemic by utilizing centralized leadership. Inspired in part by a shortage of surge intensive care unit capacity, the Israeli Ministry of Health took control of hospital referrals and admissions and pioneered a containment strategy that included significant early travel restrictions and quarantine of travelers.Footnote 38 The Ministry of Health also took advantage of Israel’s strong digital health and surveillance capabilities to implement digital tracking, although this initiative was eventually struck down by the Israeli High Court of Justice as requiring legislative authorization rather than executive action.Footnote 39

There were also favorable demographic factors at play. Israel tends to be younger than other industrialized countries, such as those in Cluster 2, due to relatively high fertility rates.Footnote 40 Ethnic segregation may have also served as a protective factor for some communities, such as the Israeli Arab population, in the first wave of infection.Footnote 41

Interestingly, Israel’s strong centralized response to the pandemic and its emphasis on technology, including digital health, may ultimately allow it to be a COVID-19 “success story.” Then-Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was able to secure a significant number of COVID-19 vaccine doses by, in part, promising a significant amount of data to manufacturers.Footnote 42 This promise was feasible because Israel had already created a national database that included the health information of 98 percent of its citizens. As a result, Israel may be the first country to immunize virtually all of its citizens over the age of sixteen and, therefore, potentially the first to control the pandemic via vaccination. Therefore, Israel may serve as a good reminder that this analysis considers the initial response and first wave of the pandemic, rather than the full life cycle of COVID-19.

V Discussion

The relative failure of the United States to slow the spread of COVID-19, along with the mediocre performance of high-development democracies in general, is continued evidence of the failure of the (Post-)Washington consensus in public health. As we look forward toward a still-hazy emerging public health paradigm, countries such as Thailand, South Korea, and Israel will likely become models that others will hope to emulate. For Israel and other similar success stories, we see a noteworthy pattern of above-average government effectiveness combined with below-average levels of democracy relative to their cluster peers.

The assumption that development and democracy are the sole predictors of pandemic preparedness and responsiveness has been challenged as agreement is emerging that Western countries have fared poorly. In an essay in the Intelligencer, “How the West Lost COVID-19,” David Wallace-Wells identifies slowness of response in the early stages of the pandemic amidst fear of how citizens might perceive rapid shutdowns as one major factor.Footnote 43 In the United States, for example, the first instinct of governments was to downplay the severity of the virus, while in East Asia, countries acted quickly and decisively despite incomplete information about the nature of the virus. This may in part be due to an arrogance that Western countries’ perceived development would shield them from the consequences of a pandemic. However, identifying precisely “how the West lost COVID-19” has been difficult. Multiple factors, including chance, contact with Italy, climate, and air conditioners, may all be at play. This is consistent with our analysis – no one set of indicators emerged as a reliable explanation for successes or failures in the early stages of the pandemic.

In noticing a tension between government effectiveness and democracy, we see a need for the future global consensus in public health to transition from a neoliberal vision of society to a social democratic one, in which the risks and costs associated with sickness are shared by the whole society, not only sick individuals, emphasizing that justice and efficiency must be linked together.Footnote 44 This linkage is desirable to avoid a world in which government effectiveness and democracy appear as tradeoffs, as they seem to be in our data, which arise from the neoliberal tradition embodied in the (Post-)Washington Consensus. In imagining the evolution of the Post-Washington Consensus in public health following COVID-19, we should cast off the centering on Washington and the neoliberal tradition that, in our analysis, fails to predict success in early pandemic responses. Instead, to prepare for the next global pandemic, we should focus more strongly on the connection between public health and democratic institutions, rather than government effectiveness in the abstract.

I Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has focused the world’s attention on the central importance of population health to the economic and social well-being of societies and to the multilateral order that depends upon a globalized, interconnected world. It has also highlighted the challenges to the democratic rule of law posed by the widely varying actions adopted by governments in response. The notion that health and democratic rights are intimately connected is not new. For example, Robin West asserts that the sovereign is given a monopoly on coercion in exchange for security against a life that is “nasty, brutish and short” and that the baseline condition of the sovereign’s legitimacy lies in the protection of human health and well-being.Footnote 1 Therefore, according to West, health protection is foundational, not peripheral, to the liberal philosophical tradition.Footnote 2 Similarly, public health and health promotion is a precondition to substantive democracy – as those hobbled by infirmity will be unable to meaningfully engage in democratic self-governance. Historically, movements for universal health care, including the adoption of the National Health Service in the United Kingdom,Footnote 3 were democratic struggles to enlarge democratic inclusion.Footnote 4 Further, as laid bare during the pandemic, health systems have a role to play in sustaining and reproducing core democratic commitments to formal and substantive equality.

Drawing both on our respective scholarship in these fields as well as on insights from two global symposia on governmental responses held during the early phase of the pandemic, this chapter links analyses of democratic institutions and their capacity to maintain fundamental rights protections with the functioning of health systems and protections for the health rights of diverse people in practice. From April 6 to May 26, 2020, the “COVID-19 and States of Emergency” symposium, co-hosted by the Verfassungsblog and Democracy Reporting International, published eighty-two reports and commentaries on states of emergency and the use of power in response to the pandemic.Footnote 5 From May 12 to June 12, 2020, the “Global Responses to COVID-19: Rights, Democracy and the Law” symposium, hosted by the Petrie-Flom Center, produced thirty Bill of Health entries, each of which responded to three questions regarding: (1) the legal vehicles used in response to the pandemic; (2) the effects of these on marginalized populations; and (3) the roles of legislative and judicial oversight.Footnote 6 The analytical reports on the early months of the pandemic were authored by over 120 contributors worldwide, including academics drawn from the fields of international and constitutional law and health and social policy, as well as judges and lawyers specializing in public, administrative, and international law. These comparative approaches contrasted with efforts in those early days to produce repositories of laws and policies enacted with no contextualization.Footnote 7 As both symposia sought a diversity of perspectives about the preexisting legal architectures, as well as complex social and political impacts of governmental responses, they are not susceptible to a simplistic tabulation. Thus, the conclusions presented in this chapter should be read as reflecting the authors’ joint interpretations of reported findings across the separate symposia.

This chapter proceeds as follows. First, it considers whether the use of emergency powers (e.g., the declaration of a constitutional state of exception or the use of legislative emergency frameworks which allow for the exceptional use of executive power outside normal constraints) is preferable to using ordinary legislation in managing the impacts on civil liberties of a health and social crisis. This chapter argues that whether countries are successful in limiting the potential for abuse of power in emergencies is dependent on the social and political environment in which the legal rules operate, as much as whether formal limitations and checks on the use of power are present. Second, the pandemic raises questions regarding the role of health policymaking and health systems as democratic institutions, which have been inexorably affected by decades of privatization and reduced social spending on health. This chapter suggests that the background rules that structure health systems (public health and care) and decision-making regarding priorities are as critical to understanding governmental responses as the legal recognition of health-related rights.

II States of Exception and Emergency

States of exception or emergency enable the exceptional use of powers, typically by the executive outside ordinary legislative processes or scrutiny, justified on the basis of the necessity of an urgent response to an emergency. By their nature and the strength of justifying urgency which calls for their use, emergency powers are at heightened risk of misuse or abuse where significant action can be taken with limited capacity for oversight, and where subsequent judicial review of executive discretion can be “so light a touch as to be non-existent.”Footnote 8 The extended duration of the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to concerns that the virus will become endemic, have extended the duration of executive dominance of decision-making,Footnote 9 leading to concerns that this will further global trends towards the autocratization and “decay” of democracies which were in motion prior to the pandemic.Footnote 10 Even as some countries have lifted many of the most restrictive measures on liberties at the time of writing, most provisions enacted have remained in place on statute books or in practice, leading to concerns that the modes of governance employed during the pandemic have normalized the exceptional in relation to public health emergencies.

Emergencies should not function as opportunities to permanently shift the balance of power toward the executive, resulting in decision-making that is all but unaccountable. Both symposia also underlined the importance of ensuring not only the limited nature of states of exception but, critically, the necessary limitations on the use of power during the emergency. For this, international human rights instruments, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the American Convention on Human Rights, and the European Convention on Human Rights, have provided guidelines for safeguards on the use of exceptional power, which are typically premised on: (1) identifying certain non-derogable rights (e.g., the prohibition on torture and the right to a fair trial); and (2) requiring the use of emergency powers to be proportionate, necessary, non-discriminatory, and temporary in nature.Footnote 11 Health emergencies, including the current pandemic,Footnote 12 have been interpreted to come within these provisions.Footnote 13

A majority of countries in the symposia declared a “state of emergency” (or the domestic equivalent: e.g., a “state of exception” or “state of catastrophe”) or relied upon some form of emergency powers in response to the pandemic. The symposia demonstrated a broad range and form of domestic design of both states of emergency regimes and on constitutional and legal safeguards on their use. Examples of constitutional states of exception ranged from highly prescriptive, tiered, and differential states of exception requiring legislative approval depending on the perceived severity of the emergency (e.g., Estonia and Peru) to open-ended and discretionary provisions providing for an exclusively executive decision on what constituted a “threat” (e.g., Cameroon, Malaysia, and Thailand). A number of states alternatively introduced new legislative (rather than constitutional) states of emergency (e.g., France and Bulgaria) or introduced new powers which were designated as “emergency.” The latter legislative forms of emergency powers would have been expected to be subject to ordinary democratic checks and balances, including parliamentary scrutiny and judicial review, though often were not, either by legislative design or the degree of deference displayed by parliaments and courts.Footnote 14

In the use of emergency power, a central question is the safeguarding of civil liberties through the permissible degree to which rights can be limited or states may derogate from rights protections. The “limitation” of rights, often as part of a domestic balancing exercise between competing rights or overriding public interest (e.g., the requirement to wear masks in public), is distinguishable from derogation, which is envisioned as a temporary suspension of certain (not all) rights during an emergency subject to a range of justificatory conditions (e.g., proportionality and temporariness) and the oversight of external human rights bodies, in the case of international instruments, or domestic courts, in the case of protections on constitutional rights. What is notable is that while nearly all states acted to place highly restrictive limitations on the exercise of rights, including movement, assembly, and worship, only a minority of these states in the initial phase of the pandemic made official notifications of derogations from international human rights instruments.Footnote 15

There is no common reason why some states did, or did not, declare a state of emergency and it should not be assumed that it was to avoid ostensibly higher levels of scrutiny which may be expected under ordinary legislative processes. For example, a number of populous states, including Brazil, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and India, eschewed a declaration, likely for political reasons to either avoid negative historical associations of abuse of emergency powers or in the underestimation or downplaying of the severity of the pandemic threat. States which did not rely on emergency provisions instead relied on ordinary health legislation. Restricting power within ordinary democratic and legal constraints is in line with what Martin Scheinin advocates as the principle of normalcy: addressing the health emergency through “normally applicable powers and procedures and insist[ing] on full compliance with human rights, even if introducing new necessary and proportionate restrictions upon human rights on the basis of a pressing social need created by the pandemic.”Footnote 16 However, in some more concerning cases, any form of parliamentary legislative procedure was abandoned in favor of executive decrees and presidential or ministerial circulars (e.g., Cameroon, India, Turkey, and Vietnam). These measures were emergency powers in effect, though were not considered so in form. The effect in practice of reliance on ersatz “ordinary” powers was the avoidance of safeguards which otherwise were designed to control power under emergency. The commonality exposed is that without a requisite degree of democratic oversight and input, the negative consequences which can arise both under a state of emergency and upon reliance on ordinary legislation are indistinguishable.

Evident from analysis of both symposia is that whether a state has declared a state of emergency is not a reliable indicator of potentially abusive executive practices. Such practices include the targeting of populations in vulnerable circumstances: for example, the Romani in Slovakia (state of emergency), prisoners in Peru (state of emergency), and religious minorities in India (no state of emergency) and Bangladesh (no state of emergency). The wider sociopolitical context is a stronger factor in gauging the likelihood of abusive practices. The autocratizing states of Hungary (declared a state of emergency) and Poland (no declared state of emergency) have both taken advantage of the pandemic to further consolidate executive power, to the detriment of the separation of powers and democratic checks and balances, with the former taking the opportunity to adopt emergency legislation empowering the executive to amend any law of any value in a way which is all but immune from any legislative scrutiny,Footnote 17 and the latter adopting questionable restrictions on human rights via executive decrees rather than through parliamentary statute, as required by the constitution for such a limitation of fundamental rights.Footnote 18 Paired with the temporary closure of courts, or the restriction of access to only a limited type of cases, and compounded by a pre-pandemic trend toward the demolition of judicial independence in both states, any effective judicial remedy is all but moot.Footnote 19

The essential focus, therefore, should be the use and not the form of power, and whether safeguards in the form of legislative oversight and/or judicial review have been effectively utilized – not whether they exist at all. However, this appears all the more challenging in times of crisis if both legislatures and the courts tend to be deferential to the actions of the executive and unwilling to exercise robust forms of oversight or review.Footnote 20 Such experience also lends support to the argument of Mexican Supreme Court Justice Alfredo Gutiérrez Ortiz Mena that while courts should be more deferential in cases where formally declared exceptions have been declared, they should exercise heightened review (“strict scrutiny”) of the arrogation of ordinary powers by the executive even in times of crisis.Footnote 21

However, there is also emerging evidence of good practices which are not dependent on an emergency/ordinary powers dichotomy, and instead reveals good governance practices inculcated within the wider sociopolitical ecosystem. Those states which aligned law and policy with principles of legality and legal certainty, as well as clarity in public communication, scrutiny, transparency in decision-making, and publication of underlying rationale for (in)action, and engagement with external expertise, civil society, and criticism to reform law and policy have, more often, correlated with higher levels of both public trust and compliance.Footnote 22 These practices are essential to effective strategies to combat the virus and the preservation of democratic legitimacy. By correlating infection and mortality rates with levels of restriction adopted, and the impact on ordinary life and governance, we can highlight countries from among the symposia which have epitomized this approach. For example, New Zealand’s strategy of early response and engaging a combination of ordinary powers aided by some emergency provisions, and framed by recommendations and social nudges, along with robust parliamentary oversight and government accountability, have correlated not only with lower infection rates but also high levels of public trust. Such practices are evident among the responses of the “best responders” to COVID-19:Footnote 23 Finland, Iceland, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. However, such “political trust needs to be continually earned, and traditions of transparency are deeply ingrained; they do not begin during pandemics.”Footnote 24

In sum, the symposia have revealed that the use of power within the wider sociopolitical context, not the form of legal authority, should be the starting point for reimagining democratic controls to contain abuses of civil liberties. First, conditionality within either constitutional provisions or domestic legal frameworks, or even under obligations to international standards on the use of emergency powers, cannot alone limit abuse. Second, neither the declaration of a state of exception nor the exclusive reliance on ordinary legislative powers is a reliable indicator of the likelihood of abuse of power during the pandemic. A stronger indicator, albeit one often more difficult to identify than legal text, is the sociopolitical ecosystem in which legal measures are operating: autocratizing states have capitalized on the emergency to further consolidate power, despite formal legal or constitutional safeguards, while states inculcating democratic values of trust and accountability prior to the pandemic, by contrast, have embodied these values in response. Thus, efforts to reform in order to mitigate the dangers of excessive restriction, arbitrary discrimination, and hypertrophied executive action through formal legal rules alone are largely ineffective, and must instead focus on building a robust democratic system of an independent judiciary and on encouraging active government engagement with parliamentary processes, including debate, review, and scrutiny.

III Health, Health Systems, and Democratic Decision-Making

The pandemic has brought far greater attention to connections between population health and health systems, on the one hand, and democratic legitimacy of government actions, on the other. The pandemic revealed clearly that inequalities in access to care, as well as in outcomes, reflect larger patterns of discrimination and marginalization within societies, and that normative commitments to the equal dignity of diverse members of the society is encoded in health systems, just as it is in justice systems, for example.Footnote 25 Reflections on these symposia suggest that it is insufficient to examine whether health-related rights (including the right to life with dignity when interpreted to include aspects of health care, e.g., India) are enshrined directly in constitutional norms or incorporated from international human rights law through constitutional blocs. It is just as critical to understand the structural conditions that enable health-related rights to be exercised in practice, including the formal and informal practices of subjecting health policies to democratic justification.

COVID-19 struck a world already reeling from multiple waves of austerity. Even in countries where universal health care is guaranteed under law (e.g., the Netherlands and the United Kingdom), the symposia underscored that governments’ role in financing and provision of public health and care has shrunk dramatically over the last few decades. Indeed, just as socioeconomic rights, such as health, were being formulated and incorporated into constitutions across much of the world, including in most states represented in the symposia, neoliberal economic governance has driven reductions in budgets for public health and increased privatization of health care sectors. International financial institutions have played no small part in driving these trends in the Global South. From the late 1980s to today, loan conditions attached to structural adjustment, fiscal consolidation, and the like have prompted steep cuts in public health spending, the flexibilization of labor in health sectors, increasingly stringent intellectual property restrictions on access to medicines imposed through trade agreements, and the privatization of services and supply chains, together with sweeping disruptions in social determinants of health.Footnote 26 At the same time, the political capacity to resolve social demands for health has been constrained by loan agreements that convert these fiscal issues or trade-related aspects of intellectual property into questions for technocratic expert panels to resolve.Footnote 27

Therefore, it is unsurprising that despite health rights being enshrined in constitutional law in each case, contributions to the symposia suggest that countries with well-functioning health care systems, particularly those considered “sacrosanct” in the political culture (e.g., Canada), are inevitably better placed to tackle a major health crisis than those with weak or dysfunctional health systems (e.g., South Africa, Argentina, and Colombia) or those whose systems were already in a state of total collapse prior to the crisis (e.g., Ecuador). Nor is it surprising that chronic shortages are often further compounded by widescale corruption when a sudden influx of emergency funds incentivizes opportunism (e.g., Nepal). However, this insight points to the need for international and comparative legal analysis to pay closer attention not just to the grafting or importing of human rights into domestic law,Footnote 28 but also to the structural changes needed, to ensure the infrastructure for fair provision, locally and globally, that legal frameworks based on neoliberal imperatives have made impossible.

The symposia further highlight the importance of decision-making processes in relation to health to the meaningfulness of health rights in practice, as well as the preservation of democratic legitimacy. At one level, at least since Rudolf Virchow’s work on the social origins of disease and the need to address epidemics through political, not merely medical, means, there has there been an awareness of public health policies and health systems as sites of democratic contestation.Footnote 29 As already noted, movements for universal health coverage were often struggles for democratic inclusion. The more recent technocratic conceptualization of health is a contingent historical response to increasingly neoliberal socioeconomic transformations, coupled with technological innovations based on accelerating medicalization after World War II, and biomedicalization in the twenty-first century.Footnote 30

Nonetheless, by the time COVID-19 emerged, decision-making processes regarding health, within health systems and beyond, had largely been exiled from democratic deliberation to insulated islands of professional expertise. As a result, during the pandemic, we have witnessed the widespread adoption of an overly simplistic dichotomy of “objective scientific truth versus political power,” coupled with considerable partisan politicization across a number of the countries included in one or both of the symposia (e.g., Brazil under President Bolsonaro and the United States under President Trump). In both symposia, this dichotomy has become encapsulated in the tension of who is (and should be) the decisionmaker, marking often a radical reformulation of roles – for example, “doctor as politician” in Croatia,Footnote 31 and “public opinion as epidemiologists” in the Netherlands.Footnote 32 Devi Sridhar, a leading public health academic, deploys an analogy to express the need for deference to infectious disease experts in setting policy: “It’s like being on a plane and the engine does not work. Everyone gives their opinion on what should happen instead of trusting the people who have engineering experience and have done that for years.”Footnote 33

However, there is a difference between politicized dismissal or cherry-picking of empirical scientific evidence and accepting that the forms of knowledge needed to respond to COVID-19 in a democracy have inherently political dimensions that go beyond the expertise of infectious disease specialists and epidemiologists. As Sheila Jasanoff wrote before the pandemic, in relation to science more broadly than health, “risk”:

is not a matter of simple probabilities, to be rationally calculated by experts and avoided in accordance with the cold arithmetic of cost-benefit analysis …. Critically important questions of risk management cannot be addressed by technical experts with conventional tools of prediction. Such questions determine not only whether we will get sick or die, and under what conditions, but also who will be affected and how we should live with uncertainty and ignorance.Footnote 34

In the reflections from both symposia, and throughout this pandemic, measures implemented to prevent or slow the spread of the virus have had a disproportionately negative impact on vulnerable populations, including the elderly, prisoners, persons with physical or mental disabilities, migrants, racial and ethnic minorities, and refugees and migrant workers. Analyses across countries of different income levels (e.g., Spain, Ireland, Chile, Colombia, Kenya) noted that the sudden onset of mass unemployment among part-time and informal workers, the shutdown of childcare and schools, and stay-at-home orders that led to spikes in domestic violence, had devastating impacts on women. For the millions living with poverty, malnutrition, or with high rates of potential comorbidities, including tuberculosis and HIV, in cramped conditions and with limited access to water (e.g., Argentina, Guatemala, Nepal, Nigeria, and South Africa), the most prevalent political and medical messaging of “stay home and wash your hands” ignored endemic socioeconomic disparity and the underlying structural inequalities which have enabled and embedded it.

There is no reason to believe that public health expertise offers a privileged domain of knowledge in weighing containment of transmission against losing access to other socioeconomic rights and basic needs, such as food, housing, and education. Indeed, Dr. Jonathan Mann, a founder of the “health and human rights movement,” argued based on his experience with HIV/AIDS that all “health policies and programs should be considered discriminatory and burdensome on human rights until proven otherwise.”Footnote 35 In the different dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic, policies dictated by utilitarian calculations of public health experts have shown themselves to be particularly apt to be rife with blind spots. Cloaked in an aura of objective, apolitical “scientificity,” and justified under the idea of safeguarding an unchallengeable good, which is made to appear of heightened necessity when coupled with a generalized fear, these prescriptions are insulated from normal democratic deliberation.

Further, the fallaciously denominated “health versus wealth” tradeoff – public health restrictions versus opening the economy – has in many countries involved dueling fields of expertise and cost-benefit calculations between economists and public health experts, as opposed to enlarging our imagination of how decisions regarding health can be brought into the realm of public reason. As Jasanoff and Hilgartner assert, as both national and international authorities consider the lessons of COVID-19:

they should revisit their established institutional processes for integrating scientific and political consensus-building. If free citizens are unable to see how expertise is serving the collective good, at all levels of governance, they will sooner rebel against expert authority than give up their independence. Just as a sound mind is said to require a sound body, so COVID-19 has shown that the credibility and legitimacy of public health expertise depends on the health of the entire body politic.Footnote 36

As reflected in the symposia, the pandemic has only heightened the urgency of grappling with the lack of public accountability and democracy in current health governance across most of the world, and imagining new institutions, processes, and methods for restoring normative questions to addressing health policy in pandemic and “normal” times. The critical role of reasoned justification for how health systems function has often been evidenced by its absence during COVID-19. For example, decisions regarding what services are deemed “essential” have often disproportionately affected sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Insights provided by both symposia indicate that decisions on whom to prioritize and where to allocate testing and treatment have also been questioned (e.g., Croatia, Slovakia, Nepal, and the Netherlands). Across societies, evidence suggests that the social legitimacy of health decisions, just as in others, is based on both sociohistorical context and in the case of local health systems the slow building of trust, which does not happen overnight when a pandemic breaks out. The reflections in these symposia confirm lessons from previous epidemics (e.g., HIV/AIDS and Ebola) in that the best way to implement public health policies, as well as preserve the legitimacy of the health system and government more broadly, is to engage a wider number of constituencies in a meaningful and equitable manner on an ongoing basis, as opposed to undertaking ad hoc consultations during times of crisis.

Whether allocating vaccines or scarce equipment, supplies, and treatments, which follow different logics, there is growing agreement among health ethicists that decision-making processes regarding health require the same principles suggested earlier for the promulgation of COVID-19 measures more broadly – as well as for expectations of democratic decision-making in general. These include: (1) explicit justification and transparency of rationales; (2) transparency about empirical and normative uncertainty; (3) openness to address and include diverse perspectives on competing criteria for decisions, ranking of criteria, and why they matter; (4) inclusion of the perspectives of marginalized and disadvantaged populations as to the formulation of choice criteria, as well as disparate impacts; (5) willingness to revise policy decisions in light of populations’ negative experiences with implemented decisions and critical feedback on the rationales for the decisions; and (6) regulation and enforcement of (1) to (5).Footnote 37 In addition to including distinct constituencies in specific allocation decisions or the tradeoffs between containment and other health concerns, such as mental health, reflections on the first phase of pandemic response in the symposia, together with other studies,Footnote 38 suggest that democratizing health policy requires making visible how the issues are framed in legal and policy analysis, including structural forms of subordination and exclusion that invariably affect distributions of health and ill-health.

In sum, the effectiveness, as well as legitimacy, of governmental responses to COVID-19 call for thinking more deeply about the role of health systems as democratic social institutions and the ways in which they formally and informally enshrine normative values from macro to micro levels in both pandemics and normal times. As Scott Burris argues, health law is not a matter of “just the formal rules, but how these rules are enacted every day” by the health care program implementers and providers, as well as users of the system.Footnote 39 The meaning of health rights, and health laws more broadly, invariably depends upon how multiple actors understand how they relate to other sets of rules and norms beyond the health system. Neither constitutionalization nor legislation enshrining health rights in formal law is an adequate indicator of the normative and social legitimacy of specific health policymaking and priority-setting in practice. Structural conditions underpinning meaningful access, together with the nature of processes for making health-related decisions and setting priorities, are equally critical.

Bringing health policy under the purview of public reason, as is taken for granted with respect to other rights, will likely call for a paradigm shift that enables diverse persons to see public health and access to care in normal times, as well as pandemics, not as the domain of technocratic experts alone, but as assets of (social) citizenship.

IV Conclusion

The global but differentiated impacts of the sweeping COVID-19 pandemic present an opportunity, and an imperative, for reflection on the legal, social, and institutional changes required for advancing public health, as well as for strengthening the rule of law moving forward. Joint reflections on the contributions to the symposia, together with other scholarship, suggest at least three insights for building stronger democratic institutional structures to withstand the pressures both of pandemic and autocratizing forces. First, the use of power within the wider sociopolitical context, not the form of legal authority, should be the starting point for reimagining democratic controls to contain abuses of civil liberties. Second, the institutional arrangements and structural conditions necessary to ensure access to public health, as well as to medical care, are as important as formal legislative regimes enshrining health-related rights. Third, democratic decision-making processes that include participation by a wide array of experts, as well as by constituencies affected, afford space to critique government (in)action, and are linked to responsive reforms are more effective both in producing equitable health outcomes and in preserving confidence in the rule of law. In short, the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated starkly that health, perhaps more dramatically than any other area of law and policy, involves what Britton-Purdy et al. refer to as “the need for political judgments about the gravest questions: who should exercise power, of what sort, and over whom? What should count as a human need, and what claims should politically recognized needs give us against the state and thus against one another? Whose dreams come true, and who is enlisted in the realization of others’ schemes?”Footnote 40

I Introduction

A viral pandemic and a change in global climate are utterly dissimilar in a physical sense. The pandemic is an abrupt emergency, while climate change is a long-term problem, though one requiring an urgent response. In a sense, both can be considered crises. Despite their differences, the pandemic and the climate crisis have many linkages. The response to the pandemic can impact the carbon emissions that drive climate change, while the pandemic’s economic effect may prompt government responses which impact such emissions. In the meantime, efforts to respond to this public health crisis and to the climate crisis must both contend with the frailties of human nature and of existing political institutions.

Section I of this chapter investigates the effect of COVID-19 on carbon emissions. There was a sharp initial reduction in emissions, with the question being how much of this reduction, if any, will persist. Section II turns to the possible impact of economic recovery measures on climate change. Some jurisdictions planned green recoveries, which may succeed in accelerating the transition to a low-carbon economy. Part III discusses the governance issues that have arisen regarding climate change and the pandemic; these governance issues have proved remarkably similar. Part IV then offers some concluding thoughts about the relationship between these two global crises.

II The Impact of the Pandemic on Carbon Emissions

The linkages between COVID-19 and climate change are complex. One connection involves fossil fuel consumption, which declined during lockdowns. Fossil fuel use is the primary cause of climate change, but may also indirectly increase susceptibility to COVID-19. Fossil fuels are also prime sources for ultra-fine particulates (known technically as PM2.5) due to emissions by power plants and vehicles. Several studies connect past air pollution levels with COVID-19 mortality rates, which is not surprising given the general association between air pollution and susceptibility to respiratory diseases. A 2019 study linked PM2.5 to 200,000 US deaths per year, mostly due to respiratory and cardiovascular issues.Footnote 1 A Harvard study found that an increase of one microgram per cubic meter in PM2.5 causes an 8 percent increase in the COVID-19 death rate.Footnote 2 Thus, jurisdictions that had taken steps to reduce carbon emissions may also have indirectly helped themselves in terms of the pandemic by reducing vulnerability due to PM2.5.

Another indirect connection between COVID-19 and climate change relates to extreme weather events, which climate change has amplified. Certain disaster response efforts, including evacuations and mass sheltering, provide opportunities for viral contagion, helping exacerbate the pandemic.Footnote 3

The most direct linkage, however, ties COVID-19 to economic dislocation and then to carbon emissions. It was initially expected that the economic shutdown associated with the virus would at least have the beneficial side effect of reducing carbon emissions. That direct effect on emissions seems to have been transitory. As we will see, however, some of the economic changes caused by the pandemic may have longer-lasting impacts on emissions.

Initially in China and then across the globe, the pandemic slashed economic activity and shut down transportation. By April 2020, emissions had fallen by about 17 percent globally and 25 percent in the United States.Footnote 4 But by mid-June, global emissions had begun to recover, leading to a roughly 9 percent decline below 2019 levels in the first half of 2020. In the United States, the Energy Information Agency estimated a 10 percent drop in carbon emissions for 2020 as a whole, with a 6 percent rebound in 2021 as the economy recovered.Footnote 5 Even if the 2020 emission cuts had been permanent, they would have been far less than what is required to meet global emissions targets.Footnote 6

In China, the world’s largest carbon emitter, emissions dropped 20 percent in early 2020, but then rebounded by April 2020 to 2019 levels, or slightly above.Footnote 7 The planning, permitting, and construction of new coal-fired power plants leaped in the first half of 2020.Footnote 8 Yet the central government also announced efforts to prioritize clean energy, cross-province transmission, and flexibility measures.Footnote 9 Thus, it is not clear how the pandemic will impact longer-term emissions growth.

The impact of the pandemic on the global oil industry was especially severe. Because of COVID-19-related restrictions on travel and the general economic downturn, oil prices crashed by almost 50 percent between December 2019 and March 2020.Footnote 10 In some cases, prices went negative, with well owners having to pay to have oil taken off their hands.Footnote 11 At one point, some oil futures dropped momentarily to a price of negative $37 as producers anticipated having to pay firms to take charge of their oil.Footnote 12 The price collapse seems to have accelerated trends in the industry due to the long-term prospects for oil usage. By June 2020, major oil companies such as Shell and BP were writing down the values of their oil and gas assets by tens of billions of dollars.Footnote 13 In September 2020, BP announced a radical shift in its strategic planning, away from petroleum and toward renewable energy.Footnote 14 The decline of the industry is mixed news in terms of emissions. The direct effect of a shift away from oil would clearly be beneficial. Yet there is also a risk connected with the economic decline of the industry. As demand declines, wells go out of use, and less solvent or responsible operators may simply abandon marginal wells without properly capping them. Those abandoned wells may result in significant environmental problems, including leakage of methane, a potent greenhouse gas.Footnote 15 Further uncertainties and additional strategic shifts took place in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which abruptly raised global oil and gas prices.