On the grounds of the Nymphenburg Schloß in Munich lies a small hermitage, the Magdalenenklause, nestled within a grove of trees among the well-manicured gardens that surround the palace. Though somewhat hidden away along the winding paths of the park’s pavilions, the building itself is unmistakable when one draws near. Composed of a disarranged collection of tiles, plaster, and stone masonry, the hermitage gives the impression of being quite antiquated, its slow decay offset by the repairs made to it over the centuries that have left its façade dilapidated but sound. The interior of the building is no less peculiar, with its southern quarter placed on what appears to be an ancient grotto and its northern end modeled on monastic chambers edged into the rock. One imagines that perhaps the Bavarian rulers of old built their palace adjacent to what had been a sacred site long before their arrival, their piety expressed by preserving the venerable sanctum near the royal estate that was soon to emerge.

4 Magdalenenklause exterior. Nymphenburg Schloß, Munich.

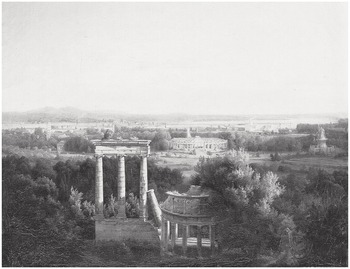

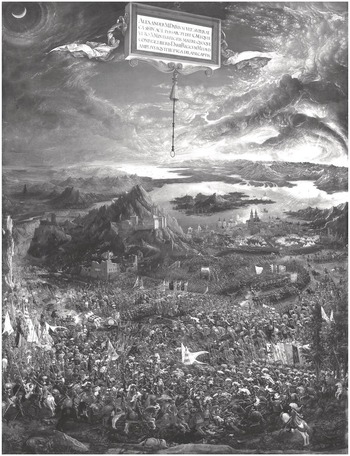

Or so it seems. The hermitage’s history is rather a more recent one, having been built in 1725 CE after much of the nearby palace was complete. Designed as a place of contemplation for the elector of Bavaria by the court architect, Joseph Effner, the Magdalenenklause represents the “artificial ruin” or “folly” architectural form that had gained popularity among rulers throughout Europe at the time.Footnote 2 Some examples, such as Frederick the Great’s Ruinenberg at Sanssouci or the Ruin of Carthage at Schloß Schönbrunn in Vienna, could even draw on a more ancient, Greco-Roman past in their designs, though such architectural remains had never been unearthed at these locations and were not indigenous to the regions in which they now stood.

5 Portrait of Ruinenberg (foreground) at Sanssouci Palace. Potsdam, Germany. Carl Daniel Freydanck, 1847.

Made to look ancient in spite of their recent appearance, the forged ruins of European estates convey a number of sentiments and impressions. Prominent among them is the aspiration to display connections with a world of ancient predecessors, affiliating the authority of a ruler to an idealized past. To take in the remains of supposedly distant ages was to be mindful of the great works of imagined forebears, above all those of Rome, and to be proximate to the power – political, cultural, aesthetic – that their ruins still conveyed to the audiences who would view them.Footnote 3 But fake ruins were also designed to be didactic, intimating the lesson that time attenuates what is created, even the most monumental and opulent of our achievements. This theme of loss would soon resonate among the Romantic poets,Footnote 4 perhaps most famously in Percy Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” which was composed during this era: “Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!” the crumbling inscription of the great pharaoh declares in the poem, though all that remains of the ruler’s accomplishments, the speaker tells us, are a statue’s two trunkless legs and its head half sunken in the sand.Footnote 5

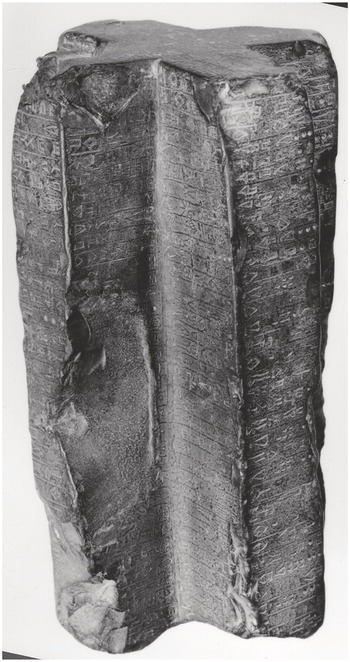

Though the manufacture of counterfeit ruins would reach its height in the eighteenth century CE, the practice of faking antiquities was already an ancient one. A striking example comes to us from the site of Tell Abu Habba, known in antiquity as the city of Sippar, located approximately 30km southwest of Baghdad in modern Iraq. On February 8, 1881, the eminent Iraqi-Assyrian archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam had a letter sent to the British Museum in London, on whose behalf Rassam was leading his excavation at the time. In his dispatch, Rassam writes of the recovery of a collection of inscribed objects found enclosed in a brick construction located in a palatial room made conspicuous by its bitumen floor.Footnote 6 The finds consisted of two terracotta cylinders nearly flawlessly preserved and, located beneath them, an “inscribed black stone, 9 inches long cut into the shape of a wheel of a treadmill, and ends [sic] at the top and bottom in the shape of a cross.”Footnote 7

When the writings on the item and associated cylinders were deciphered, the latter were found to be clearly from the time of Nabonidus, a Neo-Babylonian ruler of the sixth century BCE. But the stone object was more mysterious. Written on it was a text attributed to a ruler named Maništušu, third king of the Old Akkadian dynasty, who reigned in the late third millennium BCE – or some 1,500 years before the time of Nabonidus.Footnote 8 The purpose of the cruciform object, it appeared, was to commemorate details surrounding renovations made to the great Ebabbar temple at Sippar – a sanctuary that served as the domain of the region’s solar deity, Shamash. Preserved in the inscription were details surrounding the extensive construction measures undertaken at the site during Maništušu’s reign, including the generous funds and offerings bestowed on its priesthood by the ancient Akkadian ruler. For such reasons, the item came to be known among scholars as the “Cruciform Monument of Maništušu,” an artifact valued as an important witness to the language and history of the era surrounding this lesser-known figure of the Old Akkadian period.

6 Cruciform Monument of Maništušu. Neo-Babylonian, sixth century BCE.

Three decades after its initial publication, however, a series of studies demonstrated that the object was a forgery fabricated long after Maništušu would have ruled.Footnote 9 In a detailed discussion of how the Cruciform Monument may have emerged, Irving Finkel and Alexandra Fletcher write of how the item was likely manufactured by the Sippar priesthood at a moment when Nabonidus’ personal devotion to Sîn, the lunar deity, was viewed as a potential threat to their sanctuary and livelihood. During a renovation to the Ebabbar sanctuary, those who worked at the temple seized on the moment to bring to Nabonidus’ attention an ancient item they had “found” during the building’s restoration. On it was a venerable inscription from a distant king that happened to document strong royal financial support for the Sippar cult.Footnote 10 To further the ploy, the object was intentionally distressed to make it look antiquated, though enough of the cuneiform signs, carefully excised in an archaic cuneiform script, were safeguarded from impairment so that the claims of the inscription could still be read aloud by expert scribes before the ruler.Footnote 11 By all accounts, the gambit was successful. Nabonidus made extensive renovations to the temple and circulated copies of the monument’s inscription throughout the region, suggesting that the object’s authenticity had been accepted and, in time, even promoted by the ruler.Footnote 12

But the ruse was also successful because it was realized before Nabonidus. Of all the great rulers of the long history of the kingdoms located in regions of Mesopotamia, it is Nabonidus who stands out for his fascination with the ruins of his predecessors.Footnote 13 Nabonidus even takes on the title as the one “into whose hands [the deity] Marduk entrusted the abandoned tells (DU6meš na-du-ti),”Footnote 14 identifying himself as the divinely appointed caretaker of the ancient ruins strewn across the Babylonian empire. At over a dozen cities Nabonidus fulfilled this vow by renovating nearly thirty buildings during his relatively brief reign (556–539 BCE)Footnote 15 – a preoccupation with restoration that was driven by a strong interest in the past and in his royal predecessors. Among the cylinders that Rassam discovered near the Cruciform Monument, for example, we read of Nabonidus’ efforts at the Ebabbar temple at Sippar:Footnote 16

He [Nebuchadnezzar II] rebuilt that temple but after forty-five years the walls of that temple were caving in. I became troubled, I became fearful, I was worried and my face showed signs of anxiety … I cleared away that temple, searched for its old foundation deposit, dug to a depth of eighteen cubits, and the foundation of Narām-Sîn, the son of Sargon, which for 3200 years no king before me had seen – the god Shamash, the great Lord, revealed to me the [foundation of the] Ebabbar, the temple of his contentment.

For our purposes, a number of details stand out from this section of Nabonidus’ inscription. The first is the lengths to which Nabonidus’ workers went in an effort to rebuild the sanctuary. Though the ancient renovators lacked our technological capacity, the inscription claims that the massive structural remains from the large building site were cleared away, and the location was excavated to a depth of around 10m. This undertaking followed those from a generation before, it is further reported, when Nebuchadnezzar II had similarly attempted to renovate the ancient temple but, apparently, had done so unsuccessfully – a recurrent problem for rulers attending to temples that were already well over a millennium old and structurally unsound.Footnote 17 Lastly, what is perhaps of most interest is the expressed aim of the operation. The inscription describes Nabonidus’ primary intent as one of locating an ancient artifact, the temennu, or foundation deposit of the sanctuary, which no ruler had viewed for over 3,000 years. Even if this calculation substantially misses the mark (the distance between Narām-Sîn and Nabonidus was around 1,700 years), what is clearly conveyed in this text is an awareness that buried beneath the ground were artifacts from distant predecessors that could be unearthed and recovered.

Such discoveries and their attachments to previous ages were not restricted to Sippar alone. Nabonidus states that, at the city of Ur, he undertook similar renovations to those taking place nearly simultaneously at the temple of Sîn.Footnote 18 Once more, his workers came across items from many centuries before. Unearthed among the temple remains was a (presumably authentic) stele from the time of Nebuchadnezzar I (late twelfth century BCE) with an elaborate image of the high priestess who had once served the sanctuary, in addition to descriptions of rites and ceremonies that had been connected to the venerable temple. A further inscription details that when Nabonidus learns of the artifact and examines the image, he orders the long-abandoned office of the high priestess to be restored, installs his own daughter in the role, and gives her an archaic, ancient Sumerian name: En-nigaldi-Nanna.Footnote 19

That a putative monument from long ago could deceive the king is not then surprising, so sensitive was Nabonidus to the possibility that items from the past were resonant with meaning for the present. Nabonidus’ numerous digs have even led scholars to label him an early “archaeologist,”Footnote 20 driven by a fascination with more distant periods and predecessors that had especially taken hold among rulers in the Neo-Babylonian period (ca. 626–539 BCE). This “antiquarian interest,” as Paul-Alain Beaulieu terms it in his study of Nabonidus’ reign, could be expressed through different activities and representations, including what was one of the first recorded restorations of an ancient artifact when a nearly two-millennia-old statue of Sargon the Great was refurbished.Footnote 21 Though Nabonidus is known as the “Mad King” who famously withdrew from Babylon at the height of his reign to reside at the oasis of Teyma, he was nevertheless also a scrupulous ruler who exercised vast resources to recover and safeguard materials from former times, often in an attempt to connect himself with more venerable forebears.Footnote 22

At the outset to this study, the example of Nabonidus reminds us that we are not the first to be drawn to ruins and to wonder about what they signify, nor are we the first to locate traces of previous generations beneath the ground. And, though there is nothing in the Hebrew Bible that corresponds to the rich descriptions offered by Neo-Babylonian rulers of their attempts to unearth older structures and collect their relics, a similar fascination with distant ancestors and origins is also found across the biblical writings, as is a recognition that individual mounds (תל) and sites of wreckage (חרבת) among other ruins, are the vestiges left behind by former populations. The Hebrew scribes responsible for the biblical writings, as with the Neo-Babylonians, and as with us, were aware that they were latecomers to a world inhabited long before.

There is much, then, that connects our experience of ruins with experiences from antiquity.Footnote 23 But the divide between then and now that this chapter pursues also pertains to the example of Nabonidus, one whose attempts to disinter older buildings and recover relics can feel so similar to our own efforts at archaeological excavation today. A usurper to the throne, Nabonidus was confronted by questions of legitimacy that dogged him throughout his reign. He was also by all accounts pious, a devotee of the deity Sîn in ways that could make him politically vulnerable within a capital city and empire whose chief god of the pantheon was Marduk.Footnote 24 The motivations at work in Nabonidus’ renovation efforts, accordingly, were often driven by political calculation and personal devotion rather than by a historical interest in how previous populations – whether at Sippar, Ur, or elsewhere – once lived.Footnote 25 Having ascended to the throne via a coup, Nabonidus was eager to demonstrate his royal authority by situating himself among the great rulers of old, rebuilding what they had built and carefully attending to those remains – inscriptions, sculptures, temples – that they had left behind. Materials from the past were drawn on by Nabonidus to solidify claims of being able to rule in the present.

But what we do not find expressed within Nabonidus’ inscriptions is what Hanspeter Schaudig, in his extensive study of these texts, terms an “awareness” of historical development and change.Footnote 26 Instead, Schaudig argues that what permeates these writings is a mostly “unhistorical worldview” rendered “anachronistically,” whereby past and present are depicted as predominantly coincident and deeply connected, with Nabonidus’ rule portrayed in such a way as to foreground an abiding continuity with more ancient rulers of the region.Footnote 27 It is for such reasons that Nabonidus resolves to reinstate the practices described in the Cruciform Monument at Sippar and to reestablish the role of the high priestess at Ur, rather than relegating these conventions to past societies whose practices are now obsolete.

From this perspective, the similarities between Nabonidus’ digging activities and those excavations undertaken today, Schaudig argues, are superficial.Footnote 28 Nowhere in these royal writings is there a historical sense of the asymmetries in lived experience that distinguish past from present, of how different life under the Sargonids in the third millennium BCE would have been, for example, from that of the sixth century BCE when Nabonidus ruled. Instead, these inscriptions view the distant past as an exemplar for the present, the practices and customs of previous ages serving as an ideal to which the present should return. In short, what induced Nabonidus’ efforts to excavate old buildings were desires and motivations other than those that would arise in the eighteenth through nineteenth centuries CE, a period that developed a distinct historical mindset toward material remains not long after the time when the Magdalenenklause’s fake ruins had been completed.Footnote 29

The intent of this chapter is to chart these changing attitudes toward ruins by investigating the worlds in which they arose. This study begins in antiquity, where I draw on past decades of archaeological research to survey the landscapes that would have been visible to the biblical writers and their contemporaries. What comes to light through this investigation is an ancient terrain that enclosed ruins from two millennia of settlement activity, leaving the lands familiar to the biblical writers populated by the remains of both distant and more recent societies. Of course, passages scattered throughout the Hebrew Bible recognize the belatedness of the Israelite people and their communities in Canaan (i.e., Num 13–14; Deut 26:1–9; Judges 1; Pss 78, 105). Yet only with the advent of archaeological research has it become clear that these texts were written down within an already ancient landscape, of fallen Bronze and Iron Age settlements that still bore the traces of those communities who had once inhabited them.

But, though these writings depict cities and objects of ruination that archaeologists – thousands of years later – would unearth, their descriptions of these remains depart from our understanding of them in a fundamental detail. This point of disconnect, I will argue, is the temporal framework within which ruined sites are situated in the biblical accounts. Despite the recognition in these writings of the venerable character of many ruined settlements, how ruins are located in time is frequently opposed to how we think about the history of these remains today.

The final movement of this chapter is focalized on an era when an understanding of ruins takes a decisive turn. Following what Reinhart Koselleck describes as the Sattelzeit period,Footnote 30 this investigation examines a transitional or bridgelike era that stretched from roughly 1750–1850 CE, when pivotal new experiences of time and history emerged. This century finds significance for our study because it also marks the moment when ruins came to be thought about differently. François René de Chateaubriand, whom we will encounter later on a visit to Pompeii, describes this experience vividly in his memoirs from the early nineteenth century CE, remarking, “I have found myself caught between two ages as in the conflux of two rivers, and I have plunged into their waters”Footnote 31 What awaited Chateaubriand and those of his generation across this waterway was unknown, but what was clear to these individuals was that there was no retreat to a time before: “Turning regretfully from the old bank upon which I was born,” Chateaubriand writes, he advances “towards the unknown shore at which the new generations are to land.”Footnote 32

For Koselleck, the significance of this timeframe resides in how those who lived within it expressed a feeling of dramatic acceleration in the spheres of economics, politics, and technology, wherein the “space of experience” and “horizon of expectation” were felt to be increasingly torn apart.Footnote 33 Said differently, the past became progressively unbound from the present during this century, Koselleck contends, no longer able to serve as a paradigm for how future societies should order themselves and flourish. The lives of those in previous generations became ever more detached from contemporary experiences, it is maintained, reduced to something distant and unfamiliar. This chapter concludes by reflecting on what Paul Ricoeur terms, in his own reading of Koselleck, our “historical condition,” a horizon against which the remaining chapters of this book, devoted to the experience of the ruins in antiquity, will be set.Footnote 34

§

The lands the biblical writers inhabited were already ancient. Among the remains left behind from populations come and gone were those of monumental cities that had fallen long ago, their appearance – like the Roman ruins described by Anglo-Saxon poets in the poem that begins this chapter – conveying a world of “master-builders” from distant times, whose practices could appear more advanced than those of the present. Other remnants were of ancient temples built for deities no longer worshipped and of cultic objects whose meanings had been lost. Visible, too, was the wreckage left behind of the many kingdoms and empires who sought to control the narrow strip of land in which the biblical stories are set, a region positioned on the strategic crossroads located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Arabian Desert. Remains from the lengthy periods of Egyptian involvement in the southern Levant would have been apparent, for example, as were the traces of Aramean campaigns from the north and local resistance to these incursions. But most resonant for those behind the biblical writings were the ruins that arose from the later Assyrian and Babylonian invasions of the region, their conquests bringing the Iron Age to a close and, with that, the end of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

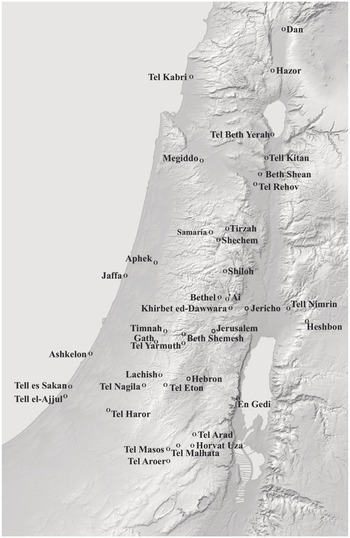

In the current chapter, we journey amid this landscape of ruins, taking in the remains that would have been visible to those who wrote and revised those texts that came to be included in the Hebrew Bible. Because these documents were composed over the course of a thousand years – extending, roughly, from the beginning of the first millennium BCE to its end – this investigation proceeds by considering key sites of ruin that existed during these centuries. We begin by examining Bronze Age ruins (ca. 3100 BCE–1175 BCE) that would have endured into the first millennium BCE, including at several locations that are referred to in the Hebrew Bible itself. This circuit then leads to another, where we investigate Iron Age ruins (ca. 1175 BCE–586 BCE) that arose nearer to the time when the biblical writings were first being composed, culminating with the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonian Empire.

That ruins were familiar to those behind the Hebrew Bible is evident throughout their writings. With hundreds of references scattered across nearly every scroll now included in this corpus, the frequency and variety of allusions to older remains in these texts attest to a widespread awareness among its authors of older locations and objects that had fallen into disrepair.Footnote 35 It is a persistent feature of these writings, furthermore, that the ruins described are not vestiges of a mythic past or located among the domains of the gods,Footnote 36 such as when the messengers of Baal descend to the ruin mounds that mark the entrance to the Kingdom of Death in the Ugaritic epic that bears this deity’s name (CAT 1.4, viii 4).Footnote 37 Rather, in the Hebrew Bible ruins are portrayed consistently as the remains of human activity, affiliated most often with what has been left behind from the destruction or abandonment of inhabited sites.

My aim here is to consider the ruined terrain that is reflected in these writings. In turning to what archaeologists have unearthed in the lands of the southern Levant, we are offered a more robust and detailed impression of the landscapes that the biblical writers and their contemporaries would have known, landscapes that will feature as well in Chapters 2–4.Footnote 38 What becomes apparent through this survey is that the depictions of ruins found in the biblical corpus are a product of lived experience, of real and meaningful encounters with the remains of past communities strewn throughout the terrain of the southern Levant.

1.1 Bronze Age Ruins

1.1.1 The Early Bronze Age II–III (ca. 3100–2500 BCE)

The antiquity of the ruins encountered by those living in the first millennium BCE could be considerable, reaching back into even the Neolithic and Chalcolithic eras, when some of the first settlements in the region, such as that at Jericho, were founded. But many of the oldest ruins still visible to the biblical writers would have descended from the Early Bronze Age (EBA) II–III periods (ca. 3100–2300 BCE). Around 3100 BCE a new settlement network appeared for the first time in the history of the southern Levant, one characterized, as Raphael Greenberg describes it, by a “permanent, fortified entity separated from its surroundings.”Footnote 39 Some of these early locations were marked by simple mud-brick walls set on stone foundations – a type of architecture that was either replaced in later centuries or slowly weathered over time.

But at certain sites more impressive fortifications persisted. At Tell el-Far’ah (North) (biblical Tirzah), a stone rampart was positioned alongside an older mud-brick one in the EBA II period, creating walls 6m thick that were further augmented with a city gate flanked by towers that reached 7m high.Footnote 40At Tel Beth Yerah, located just southwest of the Sea of Galilee, three successive walls enclosed an impressive 20ha settlement with paved streets situated on a grid pattern.Footnote 41 And the EBA fortifications at Tel Yarmuth (biblical Jarmuth) exceed even these.Footnote 42 In the most expansive EBA fortification system unearthed from the region, an initial stone wall came to be modified in time to include another enclosure built 20–30m in front of it, creating a massive rampart that stretched to 40m wide in certain sections. In the final phase of the EBA site, monumental stone platforms were placed in the space between the two walls, most likely supporting citadels or large towers that helped guard the city. To this day, the plastered, outer wall stands to a height of 7m.Footnote 43

7 Map of sites of ruins discussed in this study.

Tel Yarmuth is of particular interest because it is abandoned at the end of the EBA period and left to ruin. Around a thousand years later the acropolis of the site experiences some traces of settlement activity and more definite architectural features in the Iron I period, but the extensive lower city bears few indications of rebuilding after it was deserted.Footnote 44 The small Late Bronze Age (LBA) and Iron Age communities that existed at the location would have therefore lived among the ruins of the imposing EBA center, including the remains of the impressive Palace B and the old fortifications that enclosed this lower area of the city.Footnote 45 For these later residents who came to live atop the ruin mound, daily affairs would have been shaped by the monumental debris left behind from communities who had settled Tel Jarmuth a thousand years before, and whose building projects and public architecture far exceeded what early Iron Age communities were able to muster.

Encounters such as these with ruins from an EBA past would have been a widespread phenomenon among later populations in the southern Levant. The large city of Tel Beth Yerah mentioned above, for example, is abandoned for over 2,000 years, apart from a brief moment in the Middle Bronze Age (MBA) period when archaeological evidence suggests that a potter’s community plied their trade among the ruins from many centuries before.Footnote 46 The impressive site of Tell es Sakan, located just south of Gaza near the Mediterranean coast, is similarly abandoned after the EBA when new settlements are founded nearby within view of its ruins.Footnote 47 To the east, Khirbet ez-Zeraqun, situated on the Irbid Plateau in the Transjordan region and protected by walls over 3m thick, shares a similar fate, being abandoned along with its palace around 2700 BCE and never resettled.Footnote 48

That these EBA ruins left an impression on later populations is evident in the fact that a number of these sites are referred to in the Hebrew Bible. Jarmuth, for example, is characterized in the Book of Joshua as one of the great Amorite cities of Canaan (Josh 10:3, 5, 23; 12:11; 15:35; 21:29) even though the location would have only been a modest town in the Iron Age and Persian period when the biblical stories about it were first written and revised. Two other EBA settlements also mentioned in the Hebrew Bible stand out. The first is the city of Arad, situated at the site of Tel Arad in the eastern Negev region and referred to in a number of biblical texts that describe it as a prominent Canaanite city (i.e., Num 21:1; 33:40; Josh 12:14; Judges 1:16). Over the course of eighteen seasons of excavation a large EBA settlement came into view at the location, its community flourishing in conjunction with the copper trade that passed by it during these centuries.Footnote 49 EBA Arad was enclosed by an impressive double-gated city wall that ran 1,200m in length and featured at least eleven semi-elliptical towers to guard the settlement. One of the great fortified cities of the Levant, Arad oversaw a key trade route that coursed through the region.

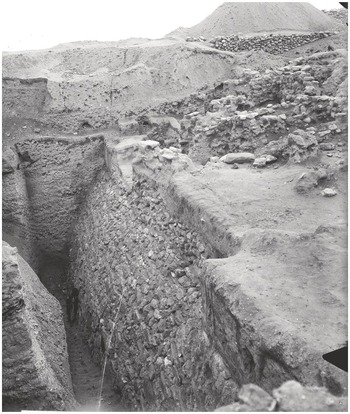

8 Tel Arad. Ruins of Iron Age fortress (background) and Bronze Age Arad (foreground).

But as with those other EBA locations, Arad was finally abandoned around 2600 BCE and was not resettled for over 1,500 years, until, ca. 950 BCE, a small Iron Age community arose amid its ruins.Footnote 50 The LBA city referred to at moments in the Hebrew Bible, much like the city of Jarmuth, did not then exist. But what was present at these locations were monumental ruins from an EBA past.

A similar relationship between ruins and biblical storytelling occurs in conjunction with the site of ’Ai (et-Tell). Situated 15km to Jerusalem’s northeast and mentioned in a number of biblical texts, ’Ai features most prominently in an extended narrative in Josh 7–8 that recounts how it was destroyed by Israelite forces. As with other EBA cities, ’Ai was settled initially in the EBA I era and subsequently grew into a large, fortified location at the beginning of the EBA II period.Footnote 51 Remains of monumental public architecture, both palaces and temples, were located on the acropolis of the city, and in time the walls of ’Ai expanded in successive building phases to become 8m wide. During this time, ’Ai was the principal city of a region that, a thousand years later, Jerusalem would come to control.

9 Bronze Age ruins of Tel Yarmuth.

Yet – much like Jarmuth, Arad, and other EBA centers – ’Ai was destroyed around 2500 BCE and abandoned for well over a thousand years. In the Iron I period a small settlement came to be built on the old terraces along the ruins of the acropolis, but this village was also soon deserted, and ’Ai was never again resettled. The biblical stories told about a great LBA city refer, therefore, to a legendary settlement that was abandoned long before the period when these biblical stories were set. But once more what prevailed at ’Ai when the biblical writers told stories about it were monumental ruins from a distant past – ruins that came to define even the location’s name in Hebrew: ’Ai, the city of “the ruins” (העי), built and fallen long ago.

Remains unearthed across disparate regions of the southern Levant indicate that “prominent ruins” from the EBA “were visible to the inhabitants of the country in later periods,” as Amihai Mazar observes in his overview of this era.Footnote 52 The biblical references to Jarmuth, Arad, and ’Ai offer further evidence of this visibility, attesting to how the biblical writers were familiar with the ruins of EBA locations. Their descriptions of these sites as imposing fortified cities suggest that these stories were shaped by the EBA remains that persisted at these locations – the remnants of ancient city walls, palaces, and temples, amid other debris, giving rise to narratives that recounted how these locations had fallen in a more distant past. Though these cities were abandoned at least a thousand years before any biblical text was written down, their monumental ruins left a deep and lasting impression on those later populations who came across them, a point apparent in the fact that the biblical writers told stories about these locations long after their demise. The distance in time between ’Ai’s downfall in the EBA and the Book of Joshua’s story of its destruction likely approached two thousand years, or a similar distance that separates us from the Roman conquest of Britain.

But what these biblical references to EBA cities also reveal is that the actual antiquity of these settlements was lost on their later storytellers. The scribes who composed these narratives appear to have been unaware that the ruins located at these sites preceded even the era of Abraham, according to biblical chronology. None of these accounts, that is, depict EBA cities as sites that came to ruin in the mid-third millennium BCE. Even ’Ai’s name suggests that the original identification of the site fell out of local memory, lost in the millennium that passed after its EBA destruction and abandonment. When stories were told about these ancient locations, the time period when these sites were destroyed was conflated with much later eras, a point to which we will turn below. Unable to distinguish between historical periods on the basis of stratigraphy, as archaeologists do today, the blurred and vague temporal framework attached to these ruins arose because knowledge of how to date these remains did not exist in antiquity, nor, for that matter, did a depth of historical time needed to account for these ancient predecessors.

1.1.2 The Middle Bronze Age II (ca. 1800–1600 BCE)

Though EBA ruins would have been part of the visible landscape of the first millennium BCE in the southern Levant, it is the ruins of the MBA II period that would have been most distinct. “If the second millennium can, in its entirety, be characterized as the Canaanite millennium,” Greenberg writes, “then the MB II must be its high-water mark, in terms of settlement expansion and the flowering of a recognizable and distinct cultural idiom.”Footnote 53 Indeed, what is significant about this era for our purposes is that it represents the “zenith of urban development” in the long Bronze Age period,Footnote 54 a timeframe when impressive monumental urban centers emerged that would, at many locations, not be surpassed until the Roman era over fifteen hundred years later.

Among MBA sites, it is once again the ruins of their fortifications that would have been most conspicuous.Footnote 55 Mazar comments,Footnote 56

During the eighteenth and seventeenth centuries B.C.E. the art of fortification reached a level of unparalleled sophistication … The idea was to surround the city with steep artificial slopes which will raise the level of the city wall high above the surrounding area and locate it as far as possible from the foot of the slope so that siege devices such as battering rams, ladders, and tunneling methods would not be effective. Two major types of fortifications were adopted, both of which were intended to achieve the same effect: the earth rampart and the glacis.

The result of these immense construction projects was the utter transformation of the southern Levant’s landscape, where city walls came to be elevated on artificial earthen embankments that rose above the terrain and appeared across the horizon as settlements set on artificial hills.

At Shechem (Tel Balatah), for example, a massive earthen rampart was created by the site’s engineers that still stands to the height of nearly 10m in its northwestern sector.Footnote 57 At Hazor, the city expanded to a remarkable 80ha during this time, or roughly twice the size of Vatican City, with its new MBA rampart rising 30m above the plain in which it sits.Footnote 58 Timnah (Tel Batash), also situated on a low alluvial plain, had its nearly precise square rampart carefully oriented toward the cardinal directions,Footnote 59 and a massive rampart, 70m in width, enclosed the city of Ashkelon on the Mediterranean coast.Footnote 60

At other sites, too, including even those of a more modest size, such as Shiloh (Khirbet Seilun) or Tel Nagila, we find the construction of substantial earthen works to support new walls that encircled these settlements.Footnote 61 The result of these monumental construction projects was a landscape that suddenly featured great mounds, artificially built, on which cities now stood.

Remains of these monumental cities would have therefore endured long after they had come to ruin. Prominent among these ruins was the cyclopean masonry used to construct city walls. Consisting of stones that could reach 3m in length and over a ton in weight, Hazor, Shechem, Jerusalem, Jericho, and Hebron – among other sitesFootnote 62 – all incorporated these massive boulders into walls built during the MBA period, many of which, because of their sheer size, can still be found at these locations today. In addition, new monumental gates and towers were constructed that far outpaced their EBA antecedents in terms of size and the sophistication of their engineering.Footnote 63 Flanking these gates were often large bastions or towers, though both architectural forms could appear throughout the course of a location’s city wall. At Gezer, a half-dozen towers were unearthed along its lengthy MBA enclosure, though it originally included many more,Footnote 64 and the remains of a number of impressive towers were also recovered from the MBA fortifications at Beth Shemesh, Hebron, and Jericho.Footnote 65

11 Tel Nagila.

Within the confines of these MBA cities, the ruins of elite residences and temples would have been conspicuous. Frequently built on a monumental scale, such public architecture contributed to the idea of these settlements as an “axis mundi,” Greenberg remarks, “linking the nether worlds to the celestial through the mediation of the man-made (or at least improved) mountain.”Footnote 66 At Tel Kabri in the western Galilee region, an elaborate 6,000m2 palace, larger than the White House, was constructed in the eastern part of the city and was notable, in part, for its large audience hall adorned with rich frescoes and paintings that bear a relationship to Minoan and Theran forms.Footnote 67 Excavations at Lachish have similarly located a large MBA palace with walls 2m thick, ashlar masonry used in its design, and rooms built with cedar wood imported from the far north in Lebanon.Footnote 68 Large palatial buildings were similarly located at Aphek, Megiddo, Tell Ajjul, and Jericho, among other sites.Footnote 69

12 Cyclopean stones used in Middle Bronze Age II wall and tower. Hebron (Tell er-Rumeideh).

13 Gezer Stelae.

Of the temples constructed during this era, the most famous are the migdal or tower-temples that were positioned on raised platforms and could be seen from a great distance.Footnote 70 Examples include those unearthed at Hazor, Megiddo, and Shechem, the latter of which had walls 5m wide that supported two large towers at its entrance hall.Footnote 71 At Tel Haror, located on the Wadi esh-Sharia, a fine temple of similar form had features that were partially preserved in situ because of an earthquake that collapsed the structure. But Hazor stands out, once again, not only for its large “Southern Temple” that stems from this period but also for a cultic precinct located to the southeast of this building that featured more than thirty standing stones in what appears to be an open-air sanctuary.Footnote 72 A large open-air sanctuary was also present at Gezer, featuring ten imposing megalithic stelae, some over 3m tall, coordinated along a north-south axis.Footnote 73

For our purposes, the great cities of the MBA find significance because of how their remains left a lasting imprint on the southern Levant’s terrain. Aaron Burke observes how the ruins of this era are distinguished by being “still visible across the landscape,” surviving “like the pyramids of Egypt” four thousand years later due to their “impressive size” and the “enormous quantity of material and labor” that were required for their formation.Footnote 74 But, as with the demise of EBA cities, so, too, did the MBA period come to a close through a series of widespread destructions and abandonments, most occurring during the decades around 1600 BCE.Footnote 75 At a few sites, such as Aphek,Footnote 76 Jaffa,Footnote 77 Hazor,Footnote 78 and Jerusalem,Footnote 79 renewed or continued settlement persisted in the centuries after. Yet, as with a number of EBA settlements, many MBA sites went unoccupied for hundreds of years after their downfall, and some for millennia, leaving their monumental ruins lying largely uninhabited. Geographically, these deserted sites could be found across the southern Levant: The large palatial estate at Tel Kabri is destroyed in the seventeenth century BCE and is not resettled until a small fortress appears in the Iron IIA period some seven centuries later;Footnote 80 Tell Nimrin, a prominent site in the Jordan valley located 16km east of Jericho, is abandoned for over five centuries after its MBA destruction;Footnote 81 and the MBA fortifications at Tel Malhata and Tel Masos, both situated in the Beersheba Valley in the Negev, are also destroyed and deserted for half a millennium.Footnote 82

Yet from the perspective of the biblical writings, the most meaningful MBA site is that of Jericho. Though preceded by a number of earlier settlements in the long history of the location, in the MBA Jericho was rebuilt on a more massive scale, expanding well beyond the confines of the EBA settlements that had once resided there. Like other locations of its time, Jericho came to be encircled by a rampart built of cyclopean stones, creating a fortification line that included the spring on which Jericho was originally founded (’Ain es-Sultan) and which enclosed a large palatial building, termed the “Hyksos Palace” in earlier excavations.Footnote 83 An impressive temple from the Spring Hill area of the settlement has also been recovered just inside the city gate of the upper city, as has a domestic quarter from the lower area of the city.Footnote 84

The history of Jericho was nevertheless a volatile one. Destroyed three different times in the MBA, the city was much reduced in the centuries that followed the final assault against it. An administrative text suggests that some activity was carried out at the site a few hundred years later in the fourteenth century BCE,Footnote 85 though physical remains of this settlement are modest and much reduced from its previous MBA stature.Footnote 86 After this period of occupation, Jericho was again abandoned apart from faint traces of activity in the Iron I period and not rebuilt until sometime in the tenth through ninth centuries BCE, or well over half a millennium after the large MBA city had been destroyed.Footnote 87

For the biblical writers, Jericho was therefore a site of ruins. These remains would have descended from successive cities built and destroyed over the course of two thousand years prior to when the biblical stories about the location were first written down. Even the notable late Iron Age settlement that eventually arose at Jericho would have been surrounded by prominent ruins from a MBA past, particularly from the massive rampart and defensive fortifications that had once guarded the city. If the large and monumental city of the LBA portrayed in the famous story about its downfall in the Book of Joshua did not, then, exist (Josh 6), what was apparent at Jericho during the time of the biblical writers were ancient ruins from a distant past.Footnote 88 The stories told about the conquest of this site would have been in keeping with those told about the EBA cities whose ruins also gave rise to biblical accounts of how they came to be.

Among locations that continued to be occupied in the centuries after the MBA ended, the ruins of this period would have stood out to later inhabitants. Many such settlements, in fact, were located in the heart of the central hill country where a number of biblical stories are set. Shechem, Shiloh, Bethel, Jerusalem, and Hebron, for example, all contained communities who lived among the ruins left behind from the MBA period. At Shechem, later residents attempted to reuse what they could salvage of the MBA fortification system in the centuries that followed,Footnote 89 and recent excavations from Hebron suggest that the large MBA rampart was still in use in the Iron Age II period many centuries later, with new fortification elements added to it at this time.Footnote 90 Shiloh’s Iron I community built into the ruins of the MBA wall that encompassed the site to support their new structures,Footnote 91 and later residents of Jerusalem inhabited a location whose “very large” MBA wall would have been a striking feature of the landscape, attesting to Jerusalem’s importance hundreds of years before Iron Age populations occupied the site.Footnote 92 When stories were told about Israel’s early past in Canaan, this is to say, they were often performed and written down in the shadows cast by the ruins of the region’s Middle Bronze Age centers. The impression left by these physical remains is perhaps most evident in the story recalled about the fall of Jericho in Joshua 6 and the miraculous collapse of its great wall. But the lesser-known accounts of the Anakim at Hebron (Num 13:22; Josh 11:21), the covenant renewal ceremony at Shechem (Josh 24), or Samuel’s early career at Shiloh (1 Sam 1–3) were stories also set at sites where monumental ruins from the MBA period endured.Footnote 93 When David conquers Jerusalem (2 Sam 5:6–9), later audiences of this story could have envisioned David surmounting the city’s old walls and occupying what remained of ruined structures from long ago, though these individuals would not have known who was actually responsible for the ruins that were visible at the site or how they came to be. Of the great cities of the MBA, the biblical writers knew little of their origins or their demise.

14 Cyclopean wall. Jericho (Tell es-Sultan), 1900 CE.

1.1.3 The Late Bronze Age (ca. 1550–1175 BCE)

The settlements that appeared in the centuries that followed the MBA were often much diminished from their predecessors, both in terms of their infrastructure and the size of their populations. The traces these locations left on the landscape of the southern Levant were therefore more sporadic and less evident than those of their predecessors, at moments enclosed within the larger EBA or MBA ruins that surrounded them or lodged at sites that would become more imposing during later centuries. Nevertheless, certain remains from LBA sites would have been visible in the centuries that followed.

Some of these ruins were those left behind from Egyptian rule. During the course of the fifteenth century BCE, Egyptian incursions into the Levant brought much of the region under its control, its jurisdiction continuing for three centuries until Egyptian power finally receded with the waning of the LBA international system of which it was involved.Footnote 94 It is a feature of Egyptian policy during this era, however, that, though an Egyptian presence “was pronounced” culturally, it was “structurally limited,” its authority often exercised via intermediaries and local leaders loyal to Egypt rather than through the destruction and reconstruction of locations that Egypt sought to command.Footnote 95 The result of this strategy was that the material assemblages found among LBA sites in Canaan could evince an abundance of Egyptian wares or those influenced by them but provide less evidence of more pronounced Egyptian architectural forms.Footnote 96

At two sites familiar to the biblical writers, however, the material footprint of Egypt was more apparent. The first is the port city of Jaffa on the Mediterranean coast (Josh 19:46; 2 Chron 2:16; Jonah 1:3; Ezra 3:7). Conquered by the Egyptians during the reign of Thutmose III (ca. 1482–1428 BCE), Jaffa was turned into an Egyptian harbor in the late fifteenth century BCE and remained under Egyptian control for the next three hundred years.Footnote 97 Of the remains left behind from the Egyptian garrison stationed there, the most significant known to us is the large gatehouse attached to a fortress that existed at the city during this time. The monumental façade is the most striking feature of this structure, bearing a large inscription of Ramesses II that was positioned along a passageway over 4m high and guarded by two large towers. After its destruction ca. 1125 BCE, the Ramesses Gate area evinces few traces of settlement activity until the Persian Period many centuries later, though some ephemeral Philistine material remains suggest these new inhabitants constituted a “squatter occupation” among the ruins that followed Egyptian withdrawal.Footnote 98

The second LBA city that preserved Egyptian ruins is that of Beth-Shean. Located at the confluence of the Jordan River and Jezreel Valley, the site came under Egyptian control in the fifteenth century BCE and was used as the principal administrative center for Egyptian activities in Canaan at the time.Footnote 99 In the Ramesside period of the thirteenth century BCE, Beth-Shean was rebuilt on a more monumental scale with new temples, public buildings, and a residential quarter, featuring monuments erected on behalf of Seti I and, later, of Ramesses II. The final phase of the Egyptian center (twelfth century BCE) was characterized by still more widespread Egyptian monuments and inscriptions – “unparalleled elsewhere in Canaan,”Footnote 100 its excavator observes – that may have been fashioned in an effort to promote strength and authority during a period when Egyptian power was actually under threat.

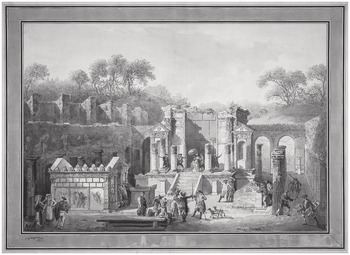

15 Replica of inscribed Ramses Gate among Egyptian ruins. Jaffa.

The twelfth century BCE garrison town would soon fall, but the ruins left behind of the Egyptian center remained: In the eleventh century BCE Canaanite settlement that followed, Egyptian monuments were carefully preserved and situated within and outside the northern temple of the site, including a large statue of Ramesses III, established, perhaps, to venerate the location’s past Egyptian heritage among inhabitants who, nevertheless, were no longer Egyptian.Footnote 101

16 Ruin mound of Beth-Shean (background), ruins of Scythopolis (foreground).

17 Ruins of Late Bronze Age Egyptian governor residence. Beth-Shean.

But the most impressive LBA city is that of Hazor. One of a handful of MBA sites in the southern Levant to escape destruction, the city transitioned into the LBA period rather seamlessly, it appears, and without major disruption.Footnote 102 The acropolis of the site was, however, reorganized in the LBA, with two of the temples in the ceremonial precinct intentionally put out of use and carefully filled with earth, including the open-air sanctuary of standing stones situated outside of the South Temple, in addition to an earlier palace.Footnote 103 In their place a massive ceremonial residence was constructed in Area A of the site, replete with a fine colonnaded courtyard, basalt orthostats that lined the main hall’s inner walls, and cedar beams that were incorporated into the brickwork throughout the structure. Nearby, another monumental building has been unearthed in the adjacent Area M, most likely a further palatial building.Footnote 104 These grand structures of the acropolis overlooked a city that retained its impressive 80ha size from centuries before, with Hazor easily the largest LBA settlement in the southern Levant.

18 Ruins of entrance to Late Bronze Age ceremonial center. Tel Hazor.

Nevertheless, the public buildings of the upper city came to a fiery end in the latter half of the thirteenth century BCE, at which time the extensive lower city was also abandoned.Footnote 105 Hazor became a monumental city of ruins in the time that followed, its acropolis strewn with remains of its massive buildings and its lower city never reoccupied. When later communities came to the city, they preserved the burnt remains of the acropolis, living among the ruins from centuries before. For five centuries, it appears, “the ruins of the Canaanite palace remained standing as a desolate hilltop,”Footnote 106 with Hazor’s later residents carefully safeguarding the ruins by prohibiting any new building activity in this area of the site.

The fall of Hazor coincided with the destruction of a number of other LBA sites in the southern Levant, including both Jaffa and Beth-Shean, but also areas of Megiddo, Aphek, and Bethel, among others.Footnote 107 Lachish, the dominant city of the southern Shephelah – and one that flourished under Egyptian influence – also falls around 1130 BCE and is abandoned for over 200 years.Footnote 108 Located to Lachish’s southwest, the fortified site of Tel Nagila is deserted near the same time, later becoming only a “hamlet or village” that was positioned amid the ruins of the old mound.Footnote 109 At Tell Kitan, located along the west bank of the Jordan River 12km north of Beth-Shean, monumental temples built near the center of the site were of such a size that there was little room for homes at the location, suggesting that the location may have functioned as a “ritual center for the surrounding settlements.”Footnote 110 During the LBA, however, Tell Kitan was destroyed, perhaps by Egyptian forces, and lay in ruins for two thousand years until it was resettled in the Early Arabic period.

At certain locations scattered throughout the southern Levant, then, ruins from the LBA would have been part of the visible landscape for those who lived in the centuries that followed. Some of these sites would have borne the traces of earlier Egyptian involvement in the region, from monuments to past pharaohsFootnote 111 to the more ubiquitous Egyptian scarabs, glyptics, faience, and pottery remains. Other locations, such as at Hazor or Tell Kitan, would have enclosed monumental remains that lay undisturbed for many centuries after the LBA ended.

In terms of the biblical writings, two features of the LBA stand out. The first is the complete absence in the Hebrew Bible of references to Egyptian control of Canaan during these centuries. Though the exodus from Egypt is the pivotal narrative of the entire biblical corpus, and though the Hebrew Bible contains a number of stories that are set in the LBA spanning from the Books of Numbers to Judges, there is not a single mention in these writings of an Egyptian presence in the Levant. This omission may be the result of the more ephemeral footprint of the Egyptians in a region that was permitted to act under the impress of local authorities and harbored few monumental Egyptian buildings outside of the administrative centers the Egyptians established. Yet, in light of the lengthy period of Egyptian hegemony in the region, the dearth of allusions to Egyptian rule among the stories told in the Hebrew Bible is remarkable. It may be that knowledge about much of this period, too, was lost by the era when the biblical writings were being formed.Footnote 112 How residents of the region understood the Egyptian ruins they would have come across in the centuries that followed Egyptian withdrawal is not conveyed in these later texts, unless these experiences were somehow woven into the strains of storytelling that pertained to the exodus story, which was said to have taken place centuries before.Footnote 113

But alongside this absence are faint glimmers of a LBA horizon that perhaps can be discerned in these writings. Stories surrounding Hazor (Josh 11), Shechem (Judges 9), Bethel (Judges 1), and Lachish (Joshua 10), for example, all situate the destruction of these locations, roughly, within the closing moments of the LBA in which they fell. Such narratives do not demonstrate that the biblical stories communicate information about what had once taken place at these sites, particularly given that the agents behind the destruction are historically unknown and that the fall of Hazor and Lachish, to cite only one example, took place a century apart and not months, as the narrative in Joshua 10–11 suggests.Footnote 114 Unlike the ruins of EBA and MBA sites, however, it may be that remnants of a few LBA locations were associated with vague memories of a past that had endured with the ruins and persisted over time at these locations, memories pertaining to a violent end long ago that brought down impressive cities in the region.Footnote 115

1.2 Iron Age Ruins

When we enter the Iron Age period, we encounter a time when many biblical texts were first written down.Footnote 116 The ruins that arose in this era would have been more immediate to the storytellers behind these writings and, consequently, the outcome of events was often experienced by societies of which the biblical writers were part or had more recently descended. Nevertheless, it is the case that Iron Age texts would have been revised and reworked further in the generations that followed this period, whether these writers resided in the Persian (ca. 530–330 BCE) or Hellenistic (ca. 330–60 BCE) eras. And for these later communities, the ruins of Jerusalem, destroyed in 586 BCE, would be the most significant for the texts they developed.

1.2.1 The Early Iron Age (Iron I–IIA, ca. 1175–830 BCE)

In the wake of Egyptian withdrawal from the Levant in the twelfth century BCE, the settlements that emerged in the early Iron Age featured predominantly small, unwalled towns and villages set apart from the larger centers located on or near the coastal plain.Footnote 117 The ruins left behind from these sites would have been mostly negligible, therefore, particularly in comparison to monumental Bronze Age remains that persisted throughout the region. And though these centuries would witness unrest, the skirmishes that occurred were typically of a local variety rather than by the design of larger empires, the terrain of the Levant being less marked by these hostilities than by those that would take place in the centuries to follow.

For our purposes, a few ruins from this period are nevertheless meaningful. Megiddo, Shechem, and Bethel, for example, were all destroyed in the Iron I period.Footnote 118 Though Megiddo was quickly resettled, Shechem and Bethel would not be rebuilt for at least a century. And even after, neither settlement would regain its monumental stature from the centuries of the MBA.Footnote 119 At Shiloh, an Iron I community arose on the MBA ruin mound that had been abandoned since the sixteenth century BCE. This Iron Age settlement would be short-lived, however, as it was destroyed in the late eleventh century BCE after perhaps only a few decades of existence.Footnote 120 Remnants of other small, abandoned highland sites may have also endured in the region, such as the modest Iron I/early Iron IIA fortress at Khirbet ed-DawwaraFootnote 121 or the fortification tower at Giloh,Footnote 122 both situated not far from Jerusalem but also, like Shiloh, abandoned after this time. Tel Rehov, a comparatively large 10ha settlement located just south of Beth-Shean, falls in the mid-ninth century BCE, and is finally abandoned a century later.Footnote 123 In the Shephelah region further to the west, the fortified site of Khirbet Qeiyafa is destroyed in the early tenth century BCE and is thereafter deserted,Footnote 124 and the impressive Iron I city of Ekron falls near the same time, with its extensive lower city not resettled for 250 years.Footnote 125

19 Ruins of Early Iron Age gate complex. Khirbet Qeiyafa.

But it is the city of Gath (Tell es-Safi) that would have left behind the most impressive ruins from this era. Located 45km southwest of Jerusalem, Gath flourished during the EBA, MBA, and Iron I–IIA periods.Footnote 126 Of these eras, however, it would be during the early Iron Age when Gath would reach its greatest prominence, becoming one of the largest cities of its time at around 40–50ha in size.Footnote 127 Recent archaeological evidence suggests that Gath’s status in the early Iron Age was derived from its role in the copper trade that originated in the Arabah region and flowed through the Elah Valley to the coast,Footnote 128 in addition to the extensive tracts of agricultural land Gath commanded from atop the hill on which it was positioned, some of which were used for olive oil production.Footnote 129 From this perspective, not only was Gath an imposing fortified city during an era when few existed in the southern Levant, but it was also an affluent one.

20 Iron Age fortifications of the lower city in Area D East, Gath (Tell es-Safi).

For such reasons, Gath was targeted by the kingdom of Damascus when its ruler, Hazael, swept south in the ninth century BCE and ravaged regions of the southern Levant. After laying siege to the location, the Arameans finally conquered Gath and destroyed it ca. 830 BCE, ending its long history of regional authority.Footnote 130 Throughout the site, evidence of Gath’s destruction has been unearthed, where an 80cm layer of ash and debris has preserved vestiges of Gath’s downfall.Footnote 131 After the Aramean conquest, Gath is abandoned for around a century until a smaller settlement emerges in the upper reaches of the ruined city toward the end of the eighth century BCE. This community, however, is also quickly ended when the Assyrian Empire invades the Levant at this time.Footnote 132 Subsequently, Gath is deserted once more and never rebuilt.

The ruins of Gath would lie exposed for centuries after the city was destroyed and abandoned, taking their place among the monumental remains of the great Bronze Age centers that had been overthrown before. Some Bronze Age fortifications at Gath, as at Hebron, appear, in fact, to have continued in use into the Iron Age, making the city’s defenses a composite of formidable architectural features from many centuries.Footnote 133 Aren Maeir writes of how the city’s former status would have been apparent to later visitors, who would have been able to view the “impressive and still visible physical remains of the city’s extent, its massive fortifications, and other architectural features.”Footnote 134 Among the wreckage present at the site would have been the remains of these fortifications and the debris of homes left exposed to the windblown sediments that had accumulated on them, the deep trenches and other remains of the siege system implemented by the Arameans at the time of Gath’s fall, and scattered human remains of those who were not buried after Gath was overrun.Footnote 135

Gath’s stature before its fall is also apparent in the biblical writings, particularly in relation to stories surrounding David in the Book of Samuel, whose connections with the city of Gath and Gittite individuals form a significant theme in his rise to power (e.g., 1 Sam 21, 27; 2 Sam 6, 15).Footnote 136 Gath’s destruction after the long period of its dominance would have been a seismic event in the early Iron Age, demonstrating to later visitors that even the largest and wealthiest of cities in the region could be overrun. Much like references to Shiloh’s former standing (e.g., Josh 18–22; 1 Sam 1–4) or the brief account of Bethel’s capture (Judges 1:22–26), stories connected to early Iron Age locations can be found within the biblical writings, even if the accounts as we have them now are more the creation of the centuries that followed Gath’s destruction than when it stood.Footnote 137

But one explanation for the appearance of these narratives is the ruins that prevailed. At both Gath and Shiloh, monumental remains stood among locations otherwise mostly abandoned, both also positioned on key transit routes that cut through the terrain of the southern Levant. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that the remains of both sites are referred to explicitly in later biblical texts. In the Book of Amos, for example, the leaders of Israel and Judah are summoned to “go down to Gath of the Philistines” to see what had become of it a century after its fall (Amos 6:2), its great ruins serving as a warning of what might become of Jerusalem and Samaria. Later, the Book of Jeremiah provides a similar directive to visit Shiloh and take in its remains, the already ancient ruins of the city offering a sign of Jerusalem’s impending fate (Jer 7:12).

But what the archaeological record also discloses is that other remains of the early Iron Age left less of an impression on the stories that would be told about this time, particularly of an Iron I (1175–980 BCE) landscape that featured smaller settlements and villages. If Shiloh is recalled as an important settlement in the biblical writings, we are nonetheless never told how Shiloh was destroyed or by whom, nor, for that matter, are we told who resided at the fortresses of Khirbet Qeiyafa, Khirbet ed-Dawwara, or Giloh, or the circumstances surrounding the fall of Iron I Megiddo. Even an event as pivotal as David’s capture of Jerusalem in the early tenth century BCE comes to us in rather cryptic form, voiced in proverbs and difficult sayings that make it challenging to reconstruct how the biblical writers understood David’s acquisition of the city.Footnote 138 The impact registered by the ruins of smaller early Iron Age sites on biblical storytelling was often, in this sense, a rather modest one.

1.2.2 The Late Iron Age (Iron IIB–IIC, ca. 830–586 BCE)

The ruins of the late Iron Age mark the final stage of this overview. The remains left behind from this era were the result of two empires and their incursions into the southern Levant that took place a century apart. The first was that of Assyria. Beginning in the mid-eighth century BCE, the Assyrian Empire pursued a more aggressive policy under Tiglath-Pileser III toward lands in the Levant, culminating in the conquest of the kingdoms of Aleppo, Hadrach, and Damascus, among others, during the decade of the 730s BCE.Footnote 139 Israel, resisting Assyrian rule alongside Damascus in a coalition they had formed, lost the northern part of its kingdom (Galilee) in 734/733 BCE and, after a subsequent revolt, was finally conquered in 721 BCE.Footnote 140 Left in the wake of the Assyrian advance was a decimated kingdom. Avraham Faust observes that nearly all settlements in Israelite territory “show signs of destruction, damage, and decline, and most did not recover at all.”Footnote 141 Of forty-two excavated sites, a full twenty-seven were not reoccupied or were occupied only by a handful of squatters among the ruins after the Assyrian invasion, and a further twelve locations were vastly reduced in size and population in the decades after.Footnote 142 It appears that well over 90 percent of sites in Israel were affected by the Assyrian campaign, resulting in substantial demographic upheaval and the depopulation of entire regions. For those who journeyed through Israelite lands in the aftermath of Assyria’s attack, the former kingdom would have appeared, as the Book of Jeremiah describes it, like a kingdom “in ruins” (Jer 2:15).

The fallen remains of this territory would have been apparent in all quarters of its former holdings. The city of Hazor is destroyed once more at this time and evinces only “sporadic” occupation in the subsequent centuries, with a few later residents constructing poor, flimsy homes among the wreckage of the ancient city.Footnote 143 Beth-Shean is set aflame and is not settled again until the Hellenistic period half a millennium later.Footnote 144 Bethel, too, is “sparsely settled”Footnote 145 after the Assyrian advance, being rebuilt on a larger scale only centuries later during the Hellenistic period. After being subdued, Dan, Megiddo, and Tirzah are rebuilt and reoccupied afterward, though what dominates these locations are large Assyrian residences constructed by the victors to oversee the region.Footnote 146

Two decades later, the Assyrians would attack Judah. Spurred once more by revolt among their vassals in the southern Levant, the Assyrian ruler Sennacherib invaded territories in Phoenicia, Philistia, and Judah in the final years of the eighth century BCE to bring them back into the Assyrian orbit.Footnote 147 The campaign in Judah was particularly devastating. In the fertile Shephelah region in the western part of the kingdom, Sennacherib claims to have destroyed forty-six fortified settlements in an inscription recounted about this campaign. Azekah,Footnote 148 Beth-Shemesh,Footnote 149 and Tel Eton (Eglon),Footnote 150 among others, all bear witness to Sennacherib’s invasion. The most prominent site to be overrun was, however, that of Lachish,Footnote 151 with its grim downfall depicted among the famous reliefs found in the Assyrian royal palace at Nineveh.Footnote 152

21 Assyrian siege of Lachish relief panel, Southwest Palace. Nineveh.

But it would be the Babylonian Empire that would finally bring Judah and its royal center, Jerusalem, to an end.Footnote 153 With the fall of Nineveh in 612 BCE and the defeat of Egypt at the battle of Carchemish in 605 BCE, Babylon took control of the Levant, including the kingdom of Judah, which was made its vassal. After a rebellion by the Judahite king, Jehoiakim, the Babylonians laid siege to Jerusalem in 597 BCE, resulting in the deportation of an elite contingent of the city’s residents but not in the destruction of the city itself. Ten years later, a further rebellion brought Babylon to the gates of Jerusalem once more. This time, the city was not spared. Archaeological evidence for the destruction of Jerusalem has been found throughout different areas of the ancient city,Footnote 154 from the Jewish Quarter excavationsFootnote 155 to a number of sites unearthed in the City of David.Footnote 156 As the biblical description of the destruction suggests (2 Kings 25; Jer 39), much of Jerusalem was burned to the ground at the time and its fortifications dismantled. The royal city that had stood for over a thousand years in the highlands was, finally, laid waste.

22 Ruins of Iron Age pillared house. Jerusalem.

In addition to Jerusalem, large swaths of Judah were also either destroyed or abandoned, joining those ruined sites in the Shephelah that had been devastated a century before. Consequently, nearly every Judahite settlement was affected during these late Iron Age invasions, from the lowlands in the west to the central hills south of Jerusalem to fortified settlements located still further south in the Negeb region. Hebron,Footnote 157 Arad,Footnote 158 Lachish,Footnote 159 Jericho,Footnote 160 and En-GediFootnote 161 were all destroyed or abandoned near the time of Jerusalem’s downfall, with much more modest populations reoccupying these ruined sites in the century after. To the far southwest, Kadesh Barnea is overrun,Footnote 162 and, across the Jordan to the east, the city of Heshbon also falls,Footnote 163 both of which are sparsely settled in the Persian period. But other locations were abandoned far longer. The southern fortresses of AroerFootnote 164 and Horvat Uza,Footnote 165 for example, were deserted for many centuries after Judah’s end. The result of the Babylonian campaign was that most of the Iron Age kingdom of Judah, save the settlements just to the north of Jerusalem in the Benjamin region, was destroyed and depopulated. Demographically, the territories of Judah were so depleted that they would not recover to their former Iron Age levels for five hundred years. Much like Israel after the Assyrian campaigns of the late eighth century BCE, Judah also became a land of ruins.

The devastation wrought by the Assyrian and Babylonian empires brought the era of the Iron Age to a close. To those living in the time that followed, the landscape of the southern Levant must have appeared forlorn, its terrain featuring scores of ruined settlements that had arisen over the course of the previous two thousand years. Many of the biblical references to ruins are informed by this late Iron Age era of widespread destruction, including those in Jeremiah and Ezekiel, whose visions often surround Jerusalem’s fall. Descriptions of Jerusalem’s ruins are, in fact, the most abundant in the biblical corpus, found in the Books of Kings, Lamentations, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Haggai, Nehemiah, Ezra, and certain Psalms. In the Book of Nehemiah, written at least 150 years after the Babylonian campaign, Jerusalem is portrayed as still “in ruins” and its gates “burned with fire” (Neh 2:3, 17).

1.3 The Hebrew Bible and the Ruins That Remain

It is within this world of ruins that the biblical writers worked and lived. As with other ancient authors, such as Herodotus or Pausanias,Footnote 166 the texts composed by the biblical writers are imprinted with their descriptions of older landscapes. Perhaps the most salient feature of the ruins identified is their venerable character. This association with the past is imparted in a number of passages, such as in the references to the “ruins of old” (חרבות עולם) mentioned in Is 58:12 and 61:4, or the “enduring ruins” (משׁאות נצח) named in Ps 74:3. In Jer 44:6, the “waste and ruined” spaces from earlier in Jerusalem’s history are said to have persisted “still to this day” (כיום הזה), and in Amos 9:11 the promise is made to rebuild certain ruins so that their restored structures would appear “as in the days of old” (כימי עולם). In Ps 9, the enemies of Yahweh are described as having “disappeared into lasting ruins (חרבות לנצח), their cities you [Yahweh] have uprooted,” the destruction of these sites being so total and lasting that the memory of them had, much like those who had resided at ’Ai, “perished” (Ps 9:7).

This sense of the past is also framed by the storyteller’s present. The large rock on which the ark once rested in the field of Joshua of Beth-Shemesh (1 Sam 6:18) or the altar fashioned by Gideon at the village of Ophrah (Judges 6:24), among many other artifacts, are described in these writings as being visible “to this day” (עד היום הזה), suggesting that some time had passed between when these objects had been in use and the narrator’s own later context when stories about them were written down.Footnote 167 In Josh 11:13 and Jer 30:18 we come across depictions of ruin mounds that had formed long before the accounts that mention them, and in the great poem of Job 3 the poet evokes the rulers and counselors of the earth “who rebuild ruins for themselves” (Job 3:14), the renovated structures composed by the affluent couched in the language of death and degeneration that calls attention to how these restored ruins will, nevertheless, come to ruin once more.Footnote 168 But even those stories that recall the settlements that once existed at Hazor or Shiloh or Gath (e.g., Josh 11; Josh 18; 1 Sam 1; 1 Sam 27), each destroyed and abandoned in a more distant past, attest to an awareness of older locations that were in ruin when these documents were produced.Footnote 169

It is significant that those behind the biblical writings also recognized that a ruin mound (תל) is a product not of nature but of a settlement destroyed and, at moments, rebuilt over time.Footnote 170 This practice of building on a formerly ruined settlement is attested in the Book of Jeremiah, where the promise is made that “the city will be rebuilt atop its ruin mound” (עיר על תלה) (Jer 30:18). But more frequently the biblical writings call attention to ruin mounds that remain uninhabited. In Deut 13:17 the Israelites are commanded to burn down towns that apostatize against Yahweh, leaving them a “perpetual ruin mound” (תל עולם) never to be rebuilt, and in Josh 8:28 its eponymous leader “burned ’Ai” and made the city, once more, a “perpetual ruin mound.” In Num 21:1–3, a Canaanite city is renamed “utter destruction” (Hormah) after the invading Israelites destroy it (cf. Judges 1:17), a name that continued in use for some time afterward, it appears, or which was applied to other sites that had come to a similar end (Deut 1:44; 1 Chr 4:30). Micah’s famous prophecy of Jerusalem’s future downfall demonstrates, too, an awareness that ruin mounds not resettled could be given over to agriculture and that a number of such locations in the southern Levant were likely used for this purpose. Thus, Zion is envisioned as one day being “plowed as a field” (Micah 3:12), and, in a later vision from the Book of Isaiah, Jerusalem becomes the place where the “fatlings and kids shall feed among the ruins” (Is 5:17).

The ruins the biblical writers depict are most frequently those of a location’s defenses. Fortresses (מבצר) are repeatedly brought to such an end, not only those of foreign locations such as Moab (Is 25:12; Jer 48:18) or Edom (Is 34:13) but also the strongholds of Judah (Lam 2:2; Jer 5:17) and Israel (Is 17:3; Hosea 10:14). The walls (חומה) that comprise fortifications are also depicted in a state of ruin across a number of biblical texts, perhaps most famously at Jericho (Josh 6:20), though a similar fate awaits the great walls of Tyre (Ezek 26:4) and Babylon (Jer 51:44) and, of course, the city wall brought down around Jerusalem when it was destroyed (2 Kings 25:10). Dismantled, too, are the battlements (פנה) (Zeph 3:16) and towers (מגדל) that would have projected above these ramparts (i.e., Judges 8:17; Is 30:25; Ezek 26:9), including the greatest tower of them all at Babel, left to ruin after its builders had been scattered across the earth (Gen 11:8).

Within the confines of settlements, the phenomena most commonly associated with ruins are temple and cult. Already in 1 Kgs 9:8 we read of a warning voiced to Solomon that if he or those of future generations should not keep the commandments and ordinances set forth by Yahweh, then the temple in Jerusalem would come to ruin.Footnote 171 Indeed, throughout the Hebrew Bible threats are levied against cultic features and sanctuaries, such as those built for the worship of Baal (Judges 6:25) or used among what is described as other, foreign religious practices (Ex 34:13; Judges 2:2). In a striking example, Jehu is said to have brought down the Temple of Baal in Samaria atop its worshippers and turned it into a “latrine, as it is to this day” (2 Kgs 10:27).Footnote 172 Yet even cultic items connected specifically to the worship of Yahweh, such as the altar at Bethel (2 Kgs 23:15), or ostensibly wedded to its cult, such as those features recorded in Leviticus (Lev 26:30), are characterized as falling into ruin or potentially coming to such an end. In Amos 7:9 it is declared that the “high places of Isaac will be made desolate, and the sanctuaries of Israel ruined” (מקדשׁי ישראל יחרבו), and in Hosea (12:12) it is announced that the altars of Gilgal will become “like heaps of stones” (כגלים) in an alliterative wordplay on the location’s name. An extended description of the destruction of putative Yahwistic cultic items is found in the story of Hezekiah’s reign in 2 Kings (18:4), and in Is 64:10 the warning voiced to Solomon long before becomes realized, with the “holy and beautiful” temple being burned with fire and all the pleasant places of Zion turned to ruins.