Book contents

- The Early Christians

- Classical Scholarship in Translation

- The Early Christians

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Prologue: A Dead Body Is Lost to the World

- Chapter 1 Neither Jewish nor Pagan?

- Chapter 2 Christian Authorities

- Chapter 3 (Not) of This World

- Chapter 4 Citizens of Two Worlds

- Looking Back and Ahead

- Postscript

- Translations of Primary Sources

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of persons and places

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2023

- The Early Christians

- Classical Scholarship in Translation

- The Early Christians

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Prologue: A Dead Body Is Lost to the World

- Chapter 1 Neither Jewish nor Pagan?

- Chapter 2 Christian Authorities

- Chapter 3 (Not) of This World

- Chapter 4 Citizens of Two Worlds

- Looking Back and Ahead

- Postscript

- Translations of Primary Sources

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of persons and places

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Early ChristiansFrom the Beginnings to Constantine, pp. 428 - 459Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023

References

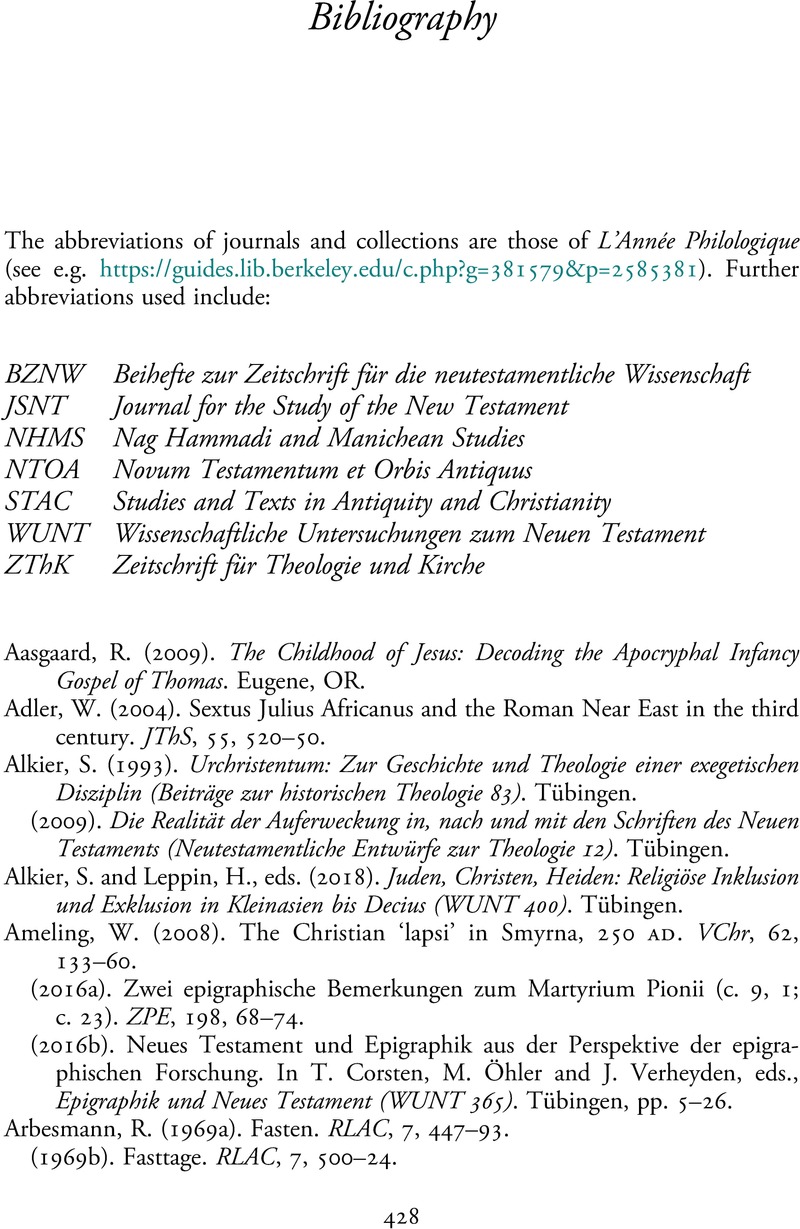

Bibliography

The abbreviations of journals and collections are those of L’Année Philologique (see e.g. https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/c.php?g=381579&p=2585381). Further abbreviations used include:

- BZNW

Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft

- JSNT

Journal for the Study of the New Testament

- NHMS

Nag Hammadi and Manichean Studies

- NTOA

Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus

- STAC

Studies and Texts in Antiquity and Christianity

- WUNT

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament

- ZThK

Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche

Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft

Journal for the Study of the New Testament

Nag Hammadi and Manichean Studies

Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus

Studies and Texts in Antiquity and Christianity

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament

Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche