42 results

Air quality and mental health: evidence, challenges and future directions

-

- Journal:

- BJPsych Open / Volume 9 / Issue 4 / July 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 July 2023, e120

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Ulysses in the World

- from Part I - Scope

-

-

- Book:

- The New Joyce Studies

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 08 September 2022, pp 110-120

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

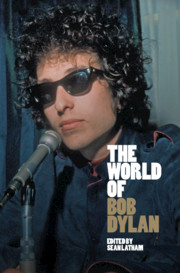

Part I - Creative Life

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp 11-58

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part IV - Political Contexts

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp 237-286

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp 341-352

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp v-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Further Reading

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp 335-340

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Songwriting

- from Part I - Creative Life

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp 31-45

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp xiv-xx

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part V - Reception and Legacy

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp 287-334

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contributors

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp viii-xiii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - Cultural Contexts

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp 145-236

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: Time to Say Goodbye Again

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp 1-10

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - Musical Contexts

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp 59-144

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - A Chronology of Bob Dylan’s Life

- from Part I - Creative Life

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Bob Dylan

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021, pp 13-19

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The World of Bob Dylan

-

- Published online:

- 21 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 May 2021

Chapter 11 - Industrialized Print

- from Part I - Historical Perspectives

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Handbook of Literary Authorship

- Published online:

- 07 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2019, pp 165-182

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 11 - Serial Modernism

- from III - The Matter of Modernism

-

-

- Book:

- A History of the Modernist Novel

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 25 June 2015, pp 254-269

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to <I>Ulysses</I>

- Published online:

- 05 October 2014

- Print publication:

- 27 October 2014, pp xxv-xxvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation