38 results

4 - Survival, Recovery, Restoration, Re-creation: The Long Life of Medieval Garments

-

-

- Book:

- Refashioning Medieval and Early Modern Dress

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 12 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 15 November 2019, pp 59-74

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - Intertext

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 181-182

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 255-264

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp viii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Opus What? The Textual History of Medieval Embroidery Terms and Their Relationship to the Surviving Embroideries c. 800–1400

- from Part I - Textile

-

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 43-68

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of publications of Gale R. Owen Crocker

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 17-24

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part I - Textile

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 25-26

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tabula Gratulatoria

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 265-265

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

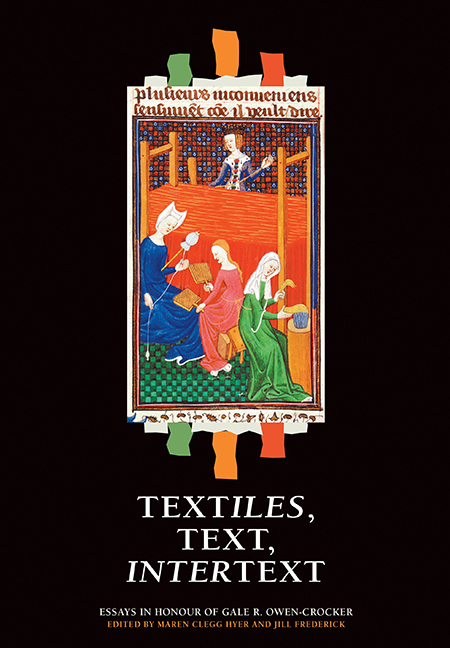

Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Essays in Honour of Gale R. Owen-Crocker

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016

Contents

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Illustrations

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - Text

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 119-120

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Landmarks of Faith: Crosses and other Free-standing Stones

-

-

- Book:

- The Material Culture of the Built Environment in the Anglo-Saxon World

- Published by:

- Liverpool University Press

- Published online:

- 17 June 2017

- Print publication:

- 31 December 2015, pp 117-136

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - “A formidable undertaking”: Mrs. A. G. I. Christie and English Medieval Embroidery

-

-

- Book:

- Medieval Clothing and Textiles 10

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 14 February 2023

- Print publication:

- 17 April 2014, pp 165-194

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Decorative Techniques 1: Changes of Surface or Form

-

- Book:

- The Art of the Anglo-Saxon Goldsmith

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 17 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 01 June 2002, pp 102-131

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - The Anglo-Saxon Goldsmith in His Society

-

- Book:

- The Art of the Anglo-Saxon Goldsmith

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 17 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 01 June 2002, pp 227-246

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- The Art of the Anglo-Saxon Goldsmith

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 17 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 01 June 2002, pp xii-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- The Art of the Anglo-Saxon Goldsmith

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 17 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 01 June 2002, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Introduction: the Background to the Study of the Anglo-Saxon Goldsmith

-

- Book:

- The Art of the Anglo-Saxon Goldsmith

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 17 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 01 June 2002, pp 1-18

-

- Chapter

- Export citation