14 results

Part III - Intertext

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 181-182

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 255-264

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp viii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of publications of Gale R. Owen Crocker

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 17-24

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part I - Textile

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 25-26

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tabula Gratulatoria

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 265-265

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

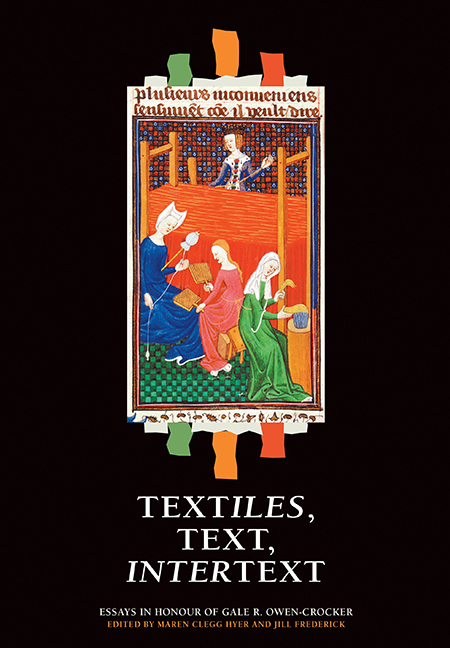

Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Essays in Honour of Gale R. Owen-Crocker

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016

Contents

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Illustrations

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - Text

-

- Book:

- Textiles, Text, Intertext

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 July 2016

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2016, pp 119-120

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - The nature of Old English verse

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature

- Published online:

- 05 May 2013

- Print publication:

- 02 May 2013, pp 50-65

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contributors

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature

- Published online:

- 05 May 2013

- Print publication:

- 02 May 2013, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - The nature of Old English verse

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature

- Published online:

- 28 May 2006

- Print publication:

- 31 May 1991, pp 55-70

-

- Chapter

- Export citation