Key Points

Funding for forests from official development assistance and other sources has trended upward since 2000, providing reason for cautious optimism. However, finance for REDD+ is in decline.

Private-sector investment remains important. Impact investment, which aims to solve pressing environmental and social problems, could make a significant contribution to the sustainability agenda.

Not all sustainable development finance promotes forest conservation. SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) aims to increase funding for agricultural production, which can incentivise the conversion of forests to farmland.

The policy of zero net deforestation is leading to some important partnerships, including with the financial sector, that aim to ensure deforestation-free commodity supply chains of key agricultural commodities.

Partnerships for sustainable development exist within a neoliberal global economic order, in which net financial flows from the Global South to the Global North negate financial flows for sustainable development.

17.1 Introduction

Successful realisation of SDG 17 is vital for attaining the other SDGs, all of which depend on securing means of implementation and forging durable partnerships for sustainable development. It is one of the most comprehensive goals as the means of implementation encompass finance, information and communication technology, capacity-building, international trade and data monitoring. SDG 17 contains a broad range of targets and indicators (see Table 17.1), some of which are analysed here. To examine the complex relationships between SDG 17 and forests, an extensive literature review and synthesis was undertaken to identify policy papers and analyses on forest-related means of implementation and partnerships for sustainable development. Websites of actors working in these areas were trawled and links followed to identify additional source material and ‘grey literature’.

Table 17.1 SDG 17 targets

| Target 17.1: Strengthen domestic resource mobilisation, including through international support to developing countries, to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection |

| Target 17.2: Developed countries to implement fully their official development assistance commitments, including the commitment by many developed countries to achieve the target of 0.7 per cent of gross national income for official development assistance (ODA/GNI) to developing countries and 0.15 to 0.20 per cent of ODA/GNI to least-developed countries |

| Target 17.3: Mobilise additional financial resources for developing countries from multiple sources |

| Target 17.4: Assist developing countries in attaining long-term debt sustainability through coordinated policies aimed at fostering debt financing, debt relief and debt restructuring, as appropriate, and address the external debt of highly indebted poor countries to reduce debt distress |

| Target 17.5: Adopt and implement investment promotion regimes for least-developed countries |

| Target 17.6: Enhance North–South, South–South and triangular regional and international cooperation on and access to science, technology and innovation, and enhance knowledge-sharing on mutually agreed terms |

| Target 17.7: Promote the development, transfer, dissemination and diffusion of environmentally sound technologies to developing countries on favourable terms |

| Target 17.8: Fully operationalise the technology bank and science, technology and innovation capacity-building mechanism for least-developed countries by 2017 and enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular information and communications technology |

| Target 17.9: Enhance international support for implementing effective and targeted capacity-building in developing countries to support national plans to implement all the Sustainable Development Goals |

| Target 17.10: Promote a universal, rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system under the World Trade Organisation |

| Target 17.11: Significantly increase the exports of developing countries, in particular with a view to doubling the least-developed countries’ share of global exports by 2020 |

| Target 17.12: Realise timely implementation of duty-free and quota-free market access on a lasting basis for all least-developed countries, consistent with World Trade Organisation decisions |

| Target 17.13: Enhance global macroeconomic stability, including through policy coordination and policy coherence |

| Target 17.14: Enhance policy coherence for sustainable development |

| Target 17.15: Respect each country’s policy space and leadership to establish and implement policies for poverty eradication and sustainable development |

| Target 17.16: Enhance the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilise and share knowledge, expertise, technology and financial resources |

| Target 17.17: Encourage and promote effective public, public–private and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships |

| Target 17.18: By 2020, enhance capacity-building support to developing countries to increase significantly the availability of high-quality, timely and reliable disaggregated data |

| Target 17.19: By 2030, build on existing initiatives to develop measurements of progress on sustainable development that complement gross domestic product, and support statistical capacity-building in developing countries |

This chapter explores ways to strengthen the means of implementation. Section 17.2 focuses in depth on financial assistance and partnerships. We do not focus on international trade, which is examined in Chapter 10. Section 17.3 examines the distinction between sustainable and unsustainable forest financing and their different impacts on forests. In particular, subsidies that incentivise the expansion of agricultural land can have a deleterious impact on forests. Section 17.4 addresses zero net deforestation (ZND), examining whether tensions exist among different SDGs. We argue that careful attention should be paid to the agro-forestry interface, with sustainable agriculture a prerequisite for achieving ZND. Building on this, Section 17.5 looks at some of the more innovative partnership arrangements that promote sustainable forest-related development. Section 17.6 briefly examines the broader structure of global economic governance, and how this negates efforts to increase the means of implementation in developing countries. Section 17.7 presents the conclusions.

17.2 Strengthening the Means of Implementation through Increased Financing

Target 17.3 aims to ‘Mobilise additional financial resources for developing countries from multiple sources’. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that achieving the SDGs will require investments in developed and developing countries of USD 5–7 trillion per year (UNCTAD 2014). For developing countries, the estimate is USD 3.3–4.5 trillion. At today’s level of investment – public and private – an annual shortfall of USD 2.5 trillion is estimated for developing countries. Hence, strengthening the means of implementation, including implementing the Addis Ababa Action Agenda on financing for development (endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 2015), is essential for achieving the SDGs. In terms of forests, SDG 17 promotes the need to increase financing levels for sustainable forest management (SFM) and to enhance cooperation among public, private and non-governmental stakeholders. It has been estimated that halving deforestation rates in developing countries will cost USD 20 billion per year (Boucher Reference Boucher2008, Forest Trends 2017).

Two Complementary Typologies

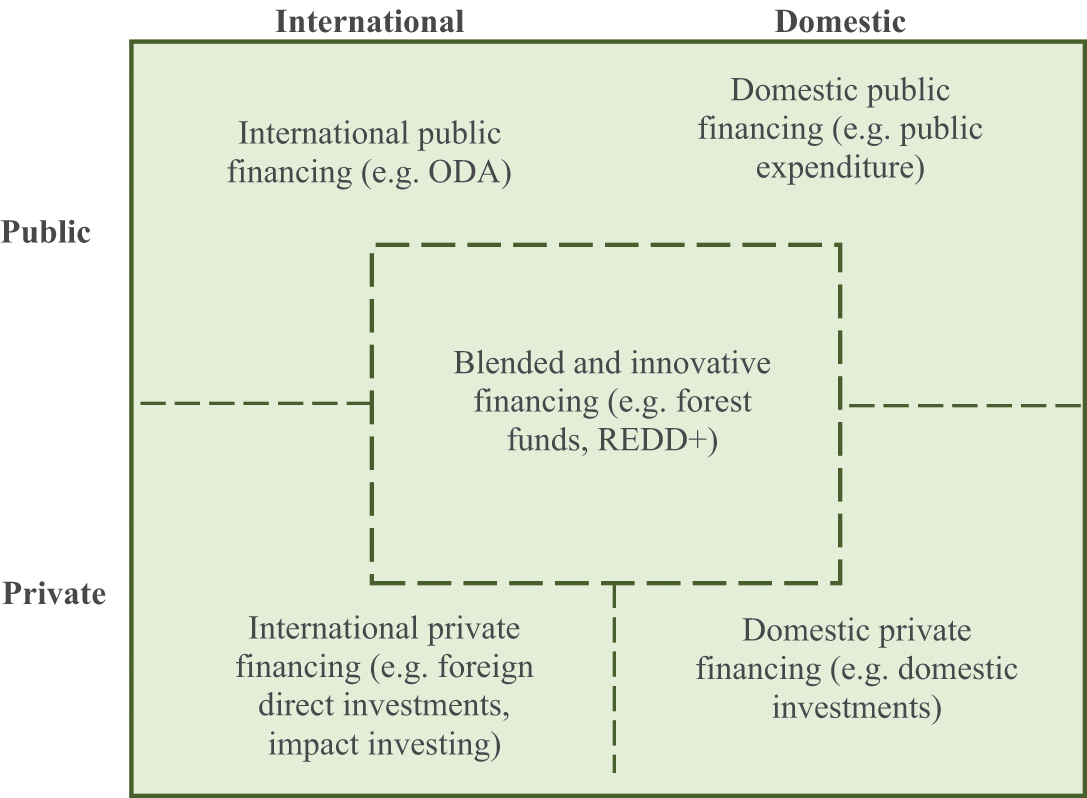

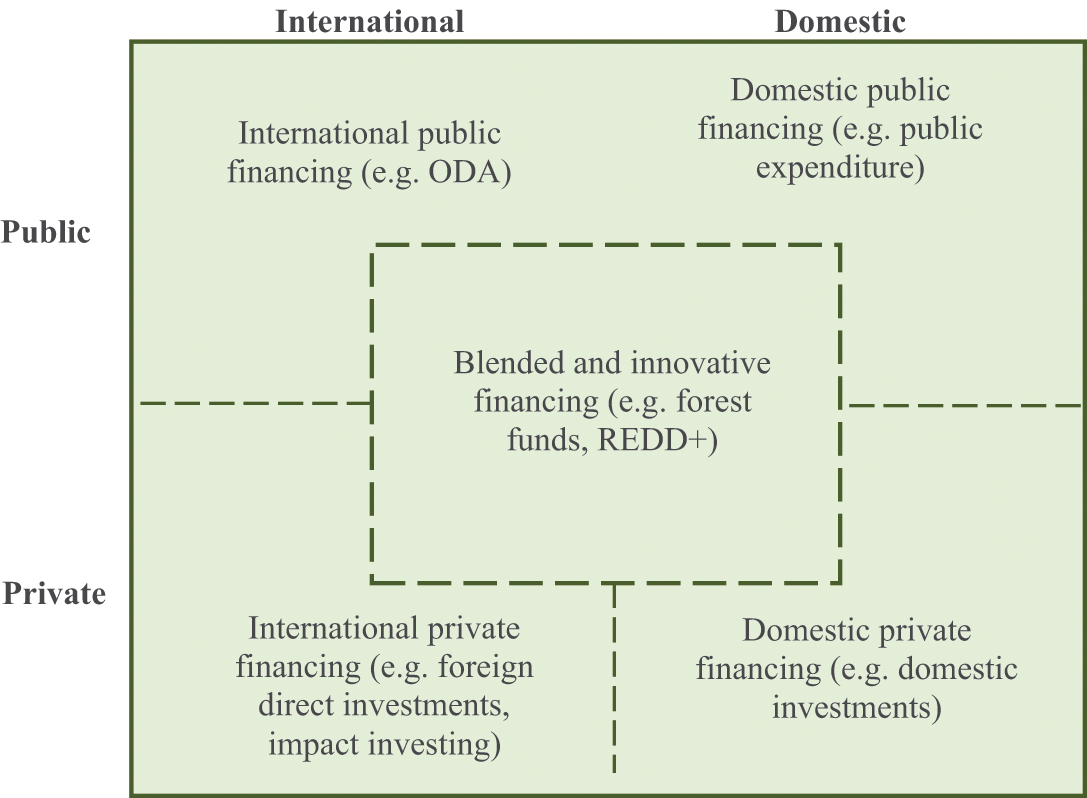

In the absence of a universally recognised definition of SFM, quantifying financing levels is a daunting challenge, further complicated by the lack of financial statistics available for sustainable investments in general (Holopainen and Wit Reference Holopainen and Wit2008). Singer (Reference Singer2016) suggests two typologies of SFM financing. The first, based on sources, is inspired by the fivefold categorisation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Agenda: international public financing, domestic public financing, international private financing, domestic private financing and – as a residual category – blended and innovative financing (Figure 17.1).

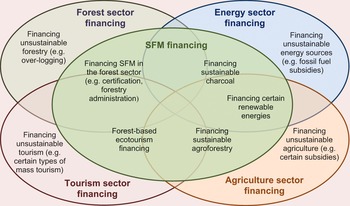

The second typology is based on the cross-sectoral nature of forests, in particular the distinction between forest financing and SFM financing. Forest financing refers to all financial sources that benefit the forest sector. Many of these sources, however, do not support sustainable forms of forest management: some forest sector investments – whether public, private, domestic or international – incentivise unsustainable management, such as overharvesting. SFM financing is a cross-sectoral category that overlaps partially with forest financing. While SFM financing comes largely from the forest sector, there are also sources outside this sector (Figure 17.2).

Figure 17.2 SFM financing as a cross-sectoral category. For simplicity, additional sectors which may impact upon SFM financing are not depicted; neither is financing in other sectors that do not impact upon SFM either positively or negatively.

17.2.1 Trends in Increased Finance

International Public Financing

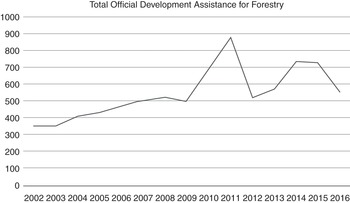

In 2017 only five members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) met the UN’s target of providing official development assistance (ODA) equal to 0.7 per cent of gross national income, called for by Target 17.2. These countries were Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden and the UK, with two non-DAC countries also meeting the target: Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (OECD 2018a). One difficulty in understanding forest-related financing is a shortage of reliable data. Nevertheless, the limited information available paints a picture of cautious optimism. The most reliable data focus on international public financing (Figure 17.3). While the overall trend in recent years is upward, closer scrutiny of national figures reveals volatility over space and time (Singer Reference Singer2016). While only a handful of countries receives most forestry ODA each year, which countries these are changes over time and thus forestry ODA per country may increase or decrease several-fold from one year to the next. However, 27 developing countries received no forestry ODA for the period 2002–2010 (AGF 2012, Singer Reference Singer2016).

Figure 17.3 Global ODA for forestry (gross disbursements) 2002–2016 in USD millions of constant 2016 USD.

OECD figures depend on donor self-reporting, so ODA that affects forests but is not explicitly labelled forestry by donors does not appear. This is particularly relevant for contributions for Reducing Emissions for Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+), which many donors classify as climate finance. Complementary data on REDD+ financing for 2009 to 2014 by Forest Trends show significant variability: USD 1.6 billion in 2009, but just USD 0.3 billion in 2014 (Silva-Chávez et al. Reference Silva-Chávez, Schaap and Breitfeller2015).

ODA for the global forest sector, including assistance for forestry development, education and research, generally increased, with annual fluctuations between 2000 and 2015, with a low of USD 400 million in the early 2000s and a high of USD 1.15 billion in 2011 (OECD 2017a, 2017b). An uptick in commitments occurred in the early 2010s, associated with the fast-start climate finance promised by developed countries in the climate negotiations and increased funding commitments during the International Year of Forests in 2011 (OECD 2017a). At the Paris climate summit in 2015, Germany, Norway and the UK collectively committed to provide more than USD 5 billion from 2015 to 2020 to forest countries demonstrating verified emission reductions, with the summit agreeing on a collective goal of USD 100 billion by 2025 (Nakhooda et al. Reference Nakhooda, Watson and Schalatek2016).Commitments, however, do not always translate into dollars invested on the ground. Since 2011, REDD+ financing has slowly dwindled. The carbon bubble that led to speculation among private investors was short-lived. The Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), which helps developing countries implement REDD+ through financial and technical assistance, has 17 financial contributors with total commitments of more than USD 1.1 billion (FCPF 2017). However, the FCPF, UN-REDD and other REDD+ funders have been criticised for promoting a narrow focus on just one forest public good, namely carbon sequestration, while neglecting others – what has been termed the ‘climatisation’ of the global forest regime (Singer and Giessen Reference Singer and Giessen2017). This reflects a tension between SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 15 (Life on Land). By the end of 2016, 73 per cent of the 2008–2016 commitments had been deposited, of which just 36 per cent were approved for project disbursement (CFU 2017). This gap between pledged and disbursed funds reflects the challenges in moving beyond capacity-building to implementation and the impact of the global financial crisis on public-sector finances (Watson et al. Reference Watson, Patel and Schalatek2016, Norman and Nakhooda Reference Norman and Nakhooda2014).

Verchot (Reference Verchot2015) compared the popularity of REDD+ with Gartner’s Hype Cycle; it has gone from a ‘peak of inflated expectations’ into a ‘trough of disillusionment’. While the Paris Agreement (UN 2015, Article 5.2) is the first international agreement to recognise REDD+, subsequent funding pledges have been slow to materialise. In 2017 the Green Climate Fund launched a USD 500 million request for proposals on REDD+ implementation. The pledge by developed countries at COP15 in Copenhagen to mobilise USD 100 billion in climate finance by 2020, however, seems unlikely to be fulfilled (Roberts and Weikmans Reference Roberts and Weikmans2016). The likelihood of leveraging sufficient funding to meet REDD+ implementation requirements is uncertain.

International Private Financing

A consistent REDD+ figure over the years has been the low proportion of private REDD+ finance – approximately 10 per cent (Silva-Chávez et al. Reference Silva-Chávez, Schaap and Breitfeller2015, UN Environment 2016) – confirming that the central role once envisaged for the private sector has failed to materialise, leaving public donors at the forefront of REDD+ financing. Data on SFM financing from private sources are scarce. The World Bank (2008) estimated annual private investment in the forestry sector in developing countries at nearly USD 15 billion – i.e. 40 times the forestry ODA disbursed that same year. Castrén et al. (Reference Castrén, Katila, Lindroos and Salmi2014) calculated private investment in forest plantations to be USD 1.8 billion per annum; no systematic data were found on private investments in tropical natural forests. Because these figures include investments along the broad spectrum of forest management, from unsustainable to sustainable, it is near impossible to place a figure on the proportion of these investments that would support SDG 17.

From 2009 to 2014 the private sector gave USD 35 million to support national REDD+ initiatives, with a further USD 381 million for carbon offset projects through the voluntary carbon market. During this period the private sector contributed approximately 10 per cent of REDD+ finance (Environmental Defense Fund and Forest Trends 2018). Government spending on REDD+ can help to leverage additional private-sector finance through public–private partnerships. An area of increasing importance, and one that can help meet Target 17.5, is impact investment – namely, an investment made with the specific intention to help solve the world’s most pressing environmental and social problems while also generating financial returns for investors. According to the Business and Sustainable Development Commission (2017), achieving the SDGs could provide USD 12 trillion of investment opportunities and create 380 million new jobs by 2030. Examples of impact investment funds include the Mirova Land Degradation Neutrality Fund, launched in 2017, which aims to provide USD 300 million for SDG 15, including sustainable agriculture and forestry. The fund involves contributions from the private sector and government donors (Global Impact Investor Survey 2018). Institutional investors – now the main market participants in developing countries, with more than a thousand pension funds, foundations, insurance companies and others (DANA 2011, Glauner et al. Reference Glauner, Rinehart and D’Anieri2012) – show increasing interest in investing in SFM.

Forest Trends (2017) note a dramatic recent increase in conservation investments, intended to generate both a financial return and a measurable environmental result. From an average of USD 0.2 billion for the period 2004–2008, annual private investments increased tenfold by 2015 to USD 2 billion. Of this, 80 per cent went to sustainable food and fibre, 18.5 per cent to habitat conservation and 2.5 per cent to water quality and quantity. These figures indicate the growing interest of some private investors in sustainability, mainly in the USA and to a lesser extent in Europe, although investments in emerging countries are increasing.

Despite this, most private finance in developing countries continues to be directed at developing forest plantations; Brazil is an example. Although they represent only 1.3 per cent of the country’s forests, plantations produce 78 per cent of Brazil’s sawlog and veneer (Tomaselli et al. Reference Tomaselli, Hirakuri and Penno Saraiva2012). Plantations do not necessarily provide high returns, although risk-adjusted returns are higher than for natural forests. The main reason for investing in plantations is that they are much more productive systems and contribute more quickly to closing the fibre gap. Tropical forests, particularly natural forests, continue to suffer from low levels of sustainable private investment due to macroeconomic instability, weak governance systems and a lack of enabling conditions, including:

Natural forest policies and legislation: Contradictory pressures from timber industries, public opinion and international organisations lead to incoherent policies and laws.

Land tenure: Lack of clear tenure adds to the risks posed by political and economic volatility, discouraging domestic and foreign investors.

Low risk-adjusted returns: While timber exploitation in tropical natural forests is a lucrative business, profits fall once SFM is applied because of the low productivity and relatively high management costs of tropical natural forests.

Reputation and information: The technical complexity of the timber sector combined with the continued (and incorrect) portrayal of the sector as the main cause of deforestation may discourage new investments.

The idea of using private capital to achieve forest-related SDGs is not without controversy. Writing about the ‘corporate capture of biodiversity’, Lovera (Reference Lovera2017) objects to the role of corporations. She argues that they offer financial support to the SDGs to conceal their attempts to undermine them, since safeguards and standards would limit profitability. However, as private-sector corporations are publicly pressured to adopt, or altruistically seek, sustainability certification, they are likely to become an increasingly important partner in achieving forest-related SDGs. Furthermore, corporate–community partnerships can facilitate market access for commodities in ways that support community-driven forest development (Katila et al. Reference Katila, de Jong, Galloway, Pokorny and Pacheco2017).

Domestic Financing

Target 17.1 – strengthen domestic resource mobilisation – can be met through improved tax collection, tax incentives, subsidies and payments for environmental services (PES). Whether domestic financing supports SFM depends in large part on fair and effective implementation as well as other potentially countervailing policies. Domestic finance, whether public or private, is difficult to track because it varies widely among countries, with data compilation depending on the capacity and reliability of national statistics agencies. This may explain why, despite being identified as a critical source of financing for development (UN 2015), it continues to receive limited attention from analysts and decision makers. However, domestic private-sector financing is the most important source of forest-related investment in many Latin American countries, especially Brazil. In Africa, an important example is Cameroon (Box 17.1).

Box 17.1 Domestic Forest Financing in Cameroon

In Cameroon, debates over forest revenue focus on domestic financing. Cameroon has a thriving timber industry, yet until the 1990s the state received minimal revenue as company profits were generally underdeclared and repatriated abroad (Eba’a Atyi et al. Reference Eba’a Atyi, Lescuyer, Ngouhouo Poufoun and Moulendè Fouda2013). In 1994, the Forest Law introduced major changes, including an auction system for allocating timber concessions and a tax increase on timber production. Revenue increased fivefold before settling to an annual USD 52–63 million (Karsenty et al. Reference Karsenty, Roda, Milol and Fochivé2006). Revenue distribution, however, has been more problematic. As stipulated in the 1994 law, half of the annual area fee goes to local municipalities and communities, yet poverty alleviation has been minimal due to financial mismanagement. The case highlights the vast potential of tax reforms to increase domestic financing, and the need for effective allocation of tax revenues to receive equal attention.

Many countries in the tropics, and elsewhere, have systems for allocating public timber resources, with harvest and/or area-based tax schemes intended to generate forest revenue for the state. However, these exhibit varying degrees of success in terms of rent capture and the equitable and effective distribution and use of funds, particularly in terms of activities that might be associated with the SDGs. Corruption and bribery often thwart potentially positive outcomes.

17.2.2 The Bigger Picture: Coherence and Coordination

This brief overview leads to an obvious conclusion: increasing levels of financing – whether public or private, domestic or international – is only half the battle. Effective coherence, as called for by Target 17.14, is key to ensuring that financing is allocated to optimise SDG implementation.

Public financing alone will not realise the SDGs. Private financing can help close the gap, but it is generally attracted to activities with high returns, declining once these returns fall below a certain threshold due to low productivity or high risk. Public financing could leverage additional private finance in two ways: (1) focus on forest-related areas of SFM with low returns, such as conservation and community forestry that can have a positive effect on forests and people; and (2) guarantee a minimum return for private investments to compensate for low returns or high risks. Public financing is also vital for: (1) creating the enabling conditions for sustainability (e.g. related to land and governance reform, jurisdictional planning processes and capacity-building); (2) developing and piloting new approaches that, once established, may attract private investments; and (3) facilitating new partnerships.

One means of coordinating different sources of financing is national forest financing. The United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF) has developed a four step strategy for SFM:

1. Mapping priorities and needs: Identify priorities in terms of goals, objectives and financing needs.

2. Mapping existing and potential sources of financing: Identify all existing sources and potential new financing sources, such as new taxes or payments for ecosystem services.

3. Matching priorities and needs with sources: Match objectives and activities with different financing sources according to criteria such as donor preferences, profitability and risk. Activities can be funded by more than one source.

4. Creating a roadmap for mobilising finance: Match each activity with one or more stakeholder(s) responsible for implementation. Budget for the financing needs quantified in Step 1 (Singer Reference Singer2017).

Depending on the level of country ownership and donor support, national forest-finance strategies could form an effective tool in mobilising finance and implementing the SDGs. Where financing shortfalls are identified, there needs to be a mechanism for prioritising resource allocation.

17.3 Sustainable versus Unsustainable Financing

One cannot assess SFM financing without comparing it with financing for unsustainable forms of land management. The impacts of other land uses on forests are well documented, such as Myers’ (Reference Myers1981) hamburger connection. In recent years, researchers have started quantifying these cross-sectoral linkages. This is particularly important since it relates to the trade-offs among SDGs, explored in this chapter and elsewhere in this book. Lawson et al. (Reference Lawson, Blundell and Cabarle2014) calculate that commercial agriculture caused more than two-thirds of illegally cleared forests between 2010 and 2012, with Brazil and Indonesia accounting for 71 per cent of the global tropical forest area illegally converted to commercial agriculture. Most tropical deforestation is driven by four forest-risk commodities, namely palm oil, soy, cattle and timber products (including paper). Persson et al. (Reference Persson, Henders and Kastner2014) estimate that between 2000 and 2009 these four commodities accounted for a third of tropical deforestation across eight countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Democratic Republic of Congo, Indonesia, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea).

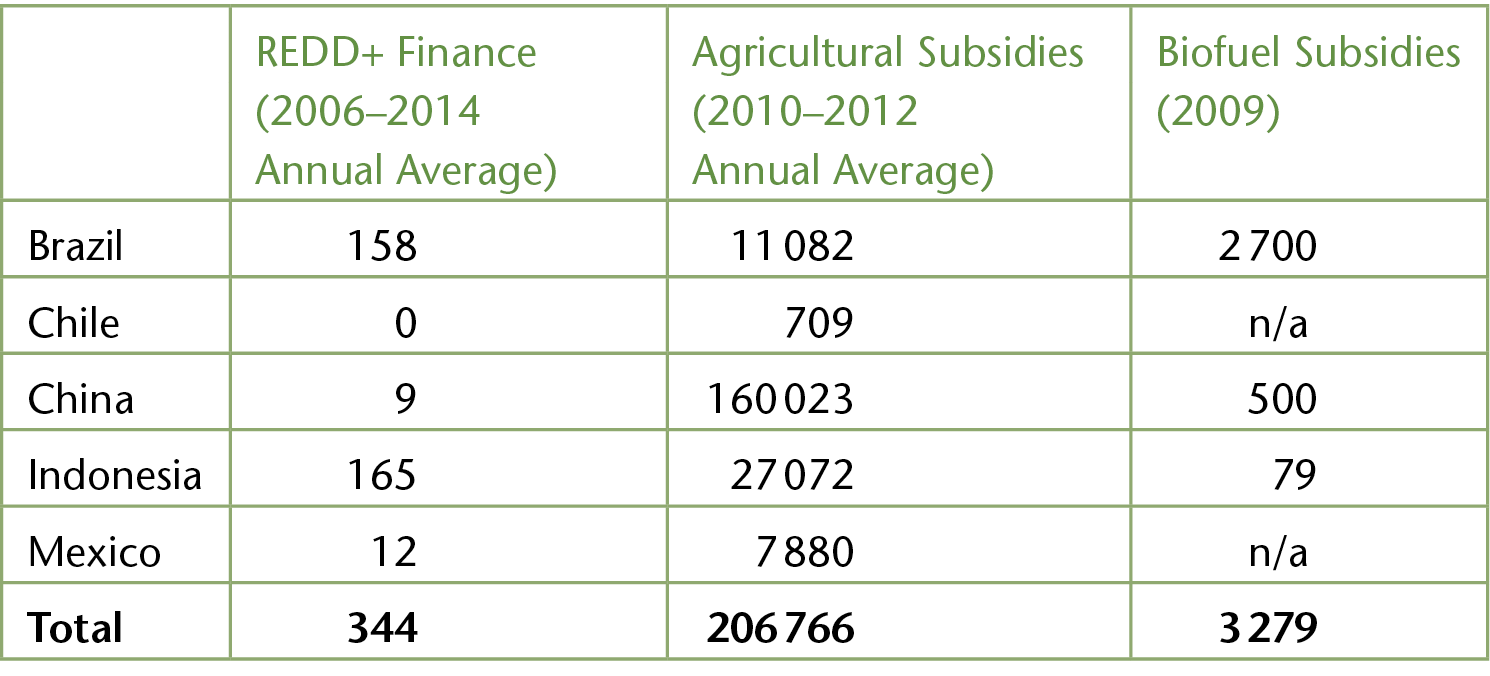

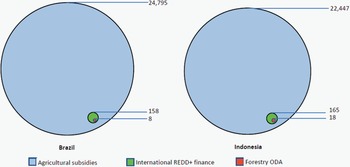

If national governments and international organisations are to reduce forest loss, they clearly must counter the deforesting effects of producing these four forest-risk commodities. An Overseas Development Institute study reveals the difficulty of doing so (McFarland et al. Reference McFarland, Whitley and Kissinger2015). With a focus on Brazil and Indonesia, which together lost 78 million ha of forest between 1990 and 2010 (FAO 2010), the authors calculate that public subsidies to beef and soy in Brazil and to palm oil and timber in Indonesia totalled USD 47.242 billion per year between 2009 and 2012. By comparison, in a period when REDD+ funding was at an all-time high, both countries received a combined USD 323 million a year for REDD+ and a mere USD 26 million a year in forestry ODA (McFarland et al. Reference McFarland, Whitley and Kissinger2015). The study compares national-level agricultural subsidies against international finance. It does not include national public-sector forest finance or consider the extent to which forest subsidies were included within agricultural subsidies.

Even so, and assuming that REDD+ financing and forestry ODA are additional, the main drivers of deforestation in both countries received as much as a staggering 136 times more domestic public funding than international public finance for forests over this period. Adding private investments to these highly lucrative agricultural commodities would further increase this figure. This is not to say that all cattle, soy, palm oil and timber production, and certainly not all related subsidies, generate deforestation (McFarland et al. Reference McFarland, Whitley and Kissinger2015). Some agricultural subsidies also tackle social and environmental issues, including forest conservation and support for sustainability (e.g. through crop intensification and land-use change restrictions). Nevertheless, if even a fraction of the financial weight of subsidies for these commodities were to generate deforestation pressures, it would dwarf public international financial support to SFM in both countries (Figure 17.4, Table 17.2 and Box 17.2).

Figure 17.4 Annual subsidies to agricultural commodities (beef and soy in Brazil; palm oil and timber in Indonesia) compared to annual international REDD+ finance and forestry ODA in Brazil and Indonesia, 2009–2012 (USD million).

Table 17.2 Comparing REDD+ finance received with domestic expenditure on biofuel and agriculture subsidies (average annual USD million)

| REDD+ Finance (2006–2014 Annual Average) | Agricultural Subsidies (2010–2012 Annual Average) | Biofuel Subsidies (2009) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 158 | 11 082 | 2 700 |

| Chile | 0 | 709 | n/a |

| China | 9 | 160 023 | 500 |

| Indonesia | 165 | 27 072 | 79 |

| Mexico | 12 | 7 880 | n/a |

| Total | 344 | 206 766 | 3 279 |

Box 17.2 Forest Financing in Latin America

Many Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) countries are active in REDD+. Twenty-one LAC countries accounted for 56 per cent (USD 819 million) of the total funds approved for REDD+ project implementation globally between 2008 and 2016 (USD 1.45 billion) (Watson et al. Reference Watson, Patel and Schalatek2016, CFU 2017). Brazil alone accounted for 45 per cent of REDD+ funding approved for implementation during this period (69 per cent of the LAC total), followed by Mexico, Colombia, Peru and Chile (CFU 2017). Brazil’s Amazon Fund has received and disbursed the largest share of REDD+ financing (Amazon Fund 2017). By the end of 2016, it had received USD 1.747 billion in pledged funding, including more than USD 1 billion from Norway through a performance-based agreement to slow forest loss and reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation. By the end of 2016, USD 1.037 billion of total pledged funds had been deposited to the fund, of which USD 576 million had been disbursed to projects (CFU 2017). Amazon Fund policies to reduce forest loss and enhance forest sustainability are credited with measurable improvements in the forest sector, with deforestation declining from 27 772 km2 in 2004 to 4403 km2 in 2012, but are associated with significant declines in agricultural commodity prices in the mid-to-late 2000s (Arima et al. Reference Arima, Barreto, Araujo and Soares-Filho2014, Fearnside Reference Fearnside2017, Nepstad et al. Reference Nepstad, McGrath and Stickler2014). Deforestation rates in Brazil have increased above the lows of the early 2010s as more forests are converted to agriculture, in part due to agriculture and biofuel subsidies that outpace climate financing for forests (Fearnside Reference Fearnside2017, Kissinger Reference Kissinger2015). While current deforestation rates in Brazil remain below those of the early 2000s, they underscore the complexity of the trade-offs among SDGs across the tropics. For example, Kissinger (Reference Kissinger2015) found agriculture and biofuel subsidies to be 600 and 9 times greater, respectively, than REDD+ financing in 5 major REDD+ countries (Table 17.2). Moreover, a review of more than 40 countries found that REDD+ readiness projects rarely include specific actions to address intersectoral conflicts relating to two or more SDGs, or to eliminate subsidies incentivising forest loss (Salvini et al. Reference Salvini, Herold, De Sy, Kissinger, Brockhaus and Skutsch2014).

This is especially relevant for two SDGs with both potential synergies and potential conflicts with forestry. First, SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) includes Target 2.A, to ‘increase investment … to enhance agricultural productive capacity in developing countries, in particular in least developed countries’. The above-mentioned subsidies could lead to forest loss, although this is less a problem of unsustainable forest management and more one of unsustainable land use, illustrating that progress to achieve policy coherence for sustainable development as called for by Target 17.14 has been limited.

Second, SDG 7 aims to ‘ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all’ (without defining sustainable). While it does not explicitly mention them, biofuels are often considered sustainable since the carbon emitted by their combustion is theoretically sequestered when crops consumed are replaced by new crop growth for future consumption. In this respect, biofuels can help achieve SDG 7 on affordable and green energy since they theoretically provide additional energy to meet growing demand while aiding climate-change mitigation. However, their large-scale adoption – e.g. in Brazil (sugarcane) and Indonesia (palm oil) – could have a significant impact on forest cover and on forest peoples in tropical countries (Acheampong et al. Reference Acheampong, Ertem, Kappler and Neubauer2017).

This section has assembled a body of evidence from several sources that leads to some important conclusions for achieving SDG 17. In particular, the financial incentives for the conversion of forests to alternative land uses such as agriculture are a fraction of those available for forest conservation and sustainable management through public and private international and domestic financing. The relationship between SFM and agricultural production is relevant to policies for ZND, to which attention now turns.

17.4 Zero Net Deforestation Commitments

While agriculture may contribute to rural economic development, food security and other SDGs, forests conversion into agricultural land remains the leading cause of deforestation in many countries. To counter this, a growing number of companies and governments have committed to eliminate deforestation from production processes and supply chains through ZND over the last decade. ZND seeks to secure production of agricultural commodities without deforesting primary forests, although deforestation that is compensated by afforestation planting elsewhere may be acceptable. Through examining ZND, this section considers the role that the agricultural and financial sectors can play in promoting SDG 17.

ZND emerged in 2008 during the Bonn Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity when the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) led a campaign supported by 67 countries calling for ZND by 2020 (WWF 2009). WWF’s commitment to ZND is significant, as the organisation has a history of forging innovative partnerships to promote ambitious targets and international rules that other actors later adopt. The WWF was one of the policy leaders behind the creation of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), with the World Bank later adopting operational policies that drew directly from FSC principles (Humphreys Reference Humphreys2006). ZND commitments require companies to identify the sources of their commodities and make supply chains traceable and transparent.

Global Forest Watch Commodities supports efforts to monitor forest activity in commodity supply chains (WRI 2017b). The Consumer Goods Forum, with some 400 member companies, has also backed ZND. The Tropical Forest Alliance 2020, launched in 2012 at Rio+20 as a global public–private partnership to reduce tropical deforestation, reduce greenhouse emissions, improve smallholder livelihoods and conserve natural habitats, has also pledged support for ZND. The New York Declaration on Forests of 2015 includes commitments from several governments and companies to remove deforestation from commodity supply chains. The idea of ZND commodity chains has grown in popularity among donors. In 2015 the Global Environment Facility (GEF) announced a USD 500 million programme to remove deforestation from commodity supply chains (GEF 2015). In 2017, Norway created a USD 400 million fund to support this initiative, aiming to raise more than USD 1.6 billion in deforestation-free agricultural investments (GEF 2017).

While ZND commitments from the private sector have transformative potential, many companies publicly committed to ZND are failing to demand that their suppliers adopt a ZND policy. Many businesses with deforestation-related commitments lack time-bound, actionable plans, and the majority do not publicly report on compliance with their own policies, making independent verification of progress difficult (Climate Focus 2016). Some business targets are aspirational only. Donofrio et al. (Reference Donofrio, Rothrock and Leonard2017) analyse 760 commitments by 447 companies to reduce deforestation in palm oil, soy, cattle, timber and pulp supply chains. Difficulties in measuring and meeting stated goals, including lack of corporate transparency (e.g. withholding information), led to about a quarter of commitments being either dormant or delayed. Furthermore, the voluntary self-regulatory nature of many commitments means that implementation gaps may emerge (Jopke and Schoneveld Reference Jopke and Schoneveld2018).

On a global scale about 27 per cent of deforestation is caused by permanent land-use change for commodity production (Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Slay, Harris, Tyukavina and Hansen2018). In Latin America some two-thirds of deforestation is driven by commercial agriculture (Kissinger et al. Reference Kissinger, Herold and de Sy2012). In particular, production of the four forest-risk commodities (Section 17.3) has caused extensive tropical deforestation and is the source of widespread conflict between agriculture companies and local people (Abram et al. Reference Abram, Meijaard and Wilson2017).

Achieving ZND requires an agriculture sector based on deforestation-free commodity chains, particularly for the forest-risk commodities. Approximately 40 per cent of global demand for the four risk commodities is accounted for by emerging producer-consumers (Brazil and Indonesia) and emerging major importers (China and India) (TFA 2018b). Effective SFM thus requires the active support of the governments of these four countries and their leading agricultural corporations. Without robust and verifiable, sustainable sourcing of these risk commodities, future expansion in their international trade will generate further deforestation pressures. This is particularly pressing given the emphasis in Target 17.11 to significantly increase the developing countries’ exports, which would enable developing countries to increase hard currency earnings. Expanding the production of agricultural commodities could contribute towards SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) but would conflict with SDG 15 (Life on Land). It seems clear that ZND targets cannot be achieved unless integrated action is taken at the agriculture-forestry interface.

Global Canopy selected 250 companies, 150 financial institutions and other actors (the ‘Forest 500’) that are at risk of being linked to tropical deforestation through potential exposure to forest-risk commodity chains and that have the greatest influence within the political economy of tropical deforestation. Their report on the Forest 500 shows that progress towards ZND has been limited. For example, although cattle production is the most important forest-risk commodity, only 17 per cent of cattle companies surveyed have a policy for forest protection, while just 8 of the 150 financial institutions surveyed have a policy for all four forest-risk commodities (Rogerson Reference Rogerson2017). A UN Environment Programme (UNEP) report found that none of the companies it surveyed have a process to quantify the risks associated with investment portfolios in forest-related agricultural commodities (UNEP 2015). The importance of the forestry–agriculture interface suggests that the transition to ZND requires a dramatic shift in investments from the drivers of deforestation towards sustainable agriculture and forestry (Climate Focus 2017).

While banks and other financial institutions that lend to or invest in companies engaged in harvesting and trading in forest-risk commodities are themselves exposed to the financial and reputational risks of deforestation, only a limited number have made progress in integrating these risks into their management structures. The important role of investment suggests a crucial role for banks and investment companies. Uptake of certification – forest certification such as the FSC and agricultural products such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) – is low in many tropical areas. However, financial institutions may foster further uptake by insisting that client companies be members of certification schemes or that the schemes be used to set minimum standards for loans (TFA 2018a). Financial institutions need to look beyond reputational risks and better understand how funding forest commodities can expose them to financial risks, especially given the growing interest of many institutional investors in impact investment (TFA 2018a). Options include introducing new financial products linked to ZND, such as green bonds and sustainable landscape bonds.

Banking-sector engagement in forest issues includes the Banking Environment Initiative (BEI), a University of Cambridge initiative of 12 leading banks that seeks to direct investment capital towards ZND business models. The BEI has partnered with the Consumer Goods Forum on the Soft Commodities Compact, which promotes partnerships between agricultural businesses and the financial sector to transform commodity supply chains of the forest-risk commodities to achieve ZND (Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership 2018). Another important initiative is the Principles for Responsible Investment, which includes an Investor Initiative for Responsible Forests focused mainly on cattle supply chains (PRI 2018).

These examples suggest the need to broaden sustainable development partnerships to involve new actors, including banks and investment companies, regional and national governments, and national and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs). The active promotion of deforestation-free commodity chains by the financial sector would mean that companies continuing to trade in products produced by deforestation would find it difficult to raise capital. Governmental involvement may be necessary to offset financial incentives discouraging the sustainable sourcing of agricultural products. In China, for example, soybean producers wishing to adopt RSPO standards may face a cost increase of USD 3–4 per metric tonne, a significant cost in a country where profit margins are thin (TFA 2018b). Government underwriting of sustainability standards (e.g. subsidies) may help overcome such market barriers.

The financial sector can thus play an important role in incentivising deforestation-free commodity chains. Noting that the most important indirect causes of deforestation are found in global financial and commodity markets, the World Resources Institute (WRI) proposes that more effective use be made of financial data and corporate governance to hold corporations accountable for how well they implement their supply chain commitments, including ZND and elimination of illegal deforestation. This requires greater corporate transparency, including providing access to relevant data (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Thoumi, Drazen and Seymour2018). Financial markets fail to distinguish between commodities produced according to ZND principles and those generating a deforestation footprint. There are no ‘deforestation free’ commodities listed on the world’s financial markets, limiting both the incentives for companies to produce such commodities and gain a price premium from them and the opportunities for responsible investors to reward companies committed to ZND (Graham et al Reference Graham, Thoumi, Drazen and Seymour2018). Many companies will find it disadvantageous to market deforestation-free products when doing so increases their costs and erodes their competitive advantage relative to more unscrupulous businesses. The two Amsterdam Declarations of 2015 – on deforestation and sustainable palm oil – aim to address this problem by generating demand for sustainable commodities and supporting the implementation of private-sector commitments to deforestation-free commodity supply chains (Partnership for Forests 2017, 2018).

One mechanism that could enable agricultural businesses to internalise the financial risks of producing deforestation-free products is a new global data platform on corporate data and forest risks. This could be structured around the Accountability Framework, which provides a set of definitions and core principles for establishing, implementing and monitoring ethical supply chain commitments (Accountability Framework 2018). Such a database would document the financial risks of investing in commodities produced through deforestation. It could also document the procedures that key financial institutions expect from client businesses involved in trading forest-risk commodities and could collate company data on the performance of investors in financing deforestation-free commodity chains. This would be consistent with Target 17.8 to enhance the use of enabling technologies, including information technology for sustainable development.

The High Carbon Stock Approach (HCSA) is a multi-stakeholder initiative designed to standardise the implementation of commitments to ZND in palm oil, pulp and paper. Its members include eight of the world’s largest palm oil, pulp and paper companies, together with consumer goods manufacturers, environmental and human rights organisations, and technical organisations, including the Union of Concerned Scientists. The HCSA offers a standard approach for fulfilling ZND commitments, including a field methodology for identifying forests with a high carbon stock (HCS forests) that must be conserved. HCSA also has protocols related to the rights and livelihoods of Indigenous peoples and local communities, including the need for free, prior and informed consent (FPIC). The commitments enshrined in the HCSA are impressive but raise issues concerning the interplay between environmental protection and community rights. For example: What should happen when communities want plantation development but the HCSA requirements make it unacceptable? How can conservation of HCSA forests on community lands be reconciled with the right to FPIC? Should there be restrictions on local people’s access to and use of HCS forests? If so, what incentives and benefits are there for communities to collaborate in conservation (Colchester et al. Reference Colchester, Anderson and Nelson2016)? It is not yet clear whether a system of this kind can provide a significant level of accountability, but in the absence of legislation, the HCSA has the potential to advance norms on acceptable social and environmental practice. The case of ZND makes it clear that innovative partnerships for sustainable development can both generate innovative sources of finance and promote integrated sustainability strategies between the forest sector and other sectors.

17.5 Partnerships for Sustainable Development

Targets 17.16 and 17.17 stress the importance of partnerships and the contributions they can make to sustainable development. Advantages of sustainable development partnerships include managing complexity (Visseren-Hamakers Reference Visseren-Hamakers2013); filling governance gaps where governments are unable or unwilling to act (Visseren-Hamakers et al. Reference Visseren-Hamakers, Arts and Glasbergen2011, Visseren-Hamakers and Glasbergen Reference Visseren-Hamakers and Glasbergen2006, Von Moltke Reference Von Moltke2002); addressing deficits in regulation, participation and implementation (Biermann et al. Reference Biermann, Chan, Mert and Pattberg2007); and regularising interactions, including placing previously informal interactions on a more formal, perhaps legal, footing (Visseren-Hamakers et al. Reference Visseren-Hamakers, Leroy and Glasbergen2012).

There is nothing inherently sustainable about partnerships. Partnerships are discursive battlefields that reflect power imbalances among actors grappling with different values and principles (Arévalo and Ros-Tonen Reference Arévalo and Ros-Tonen2009). Some partnerships may promote sustainable practices, others may not. For Andonova and Levy (Reference Andonova, Levy, Stokke and Thommessen2003), the popularity of partnerships as a form of governance originates from the disengagement from sustainable development of public authorities who have ‘franchised’ environmental governance to other actors. The UNFF initiative on financing (Paramaribo Initiative) argues that because stakeholders have different levels of power, governments must establish the rules governing partnerships to ensure that the interests of weaker stakeholders, such as Indigenous communities and small enterprises, are equitably represented (Paramaribo Initiative 2008). Partnerships that include local communities are essential for achieving the SDGs (SDIA 2013, 2015, CCAFS 2017).

As discussed, a number of forest-related partnerships help achieve the SDG targets on strengthening the means of implementation, such as the FCPF, UN-REDD (Section 17.2) and the Partnerships for Forests, which supports a range of national-level forest partnerships with investment models, for example, on sustainable palm oil development as part of ZND commitments (Section 17.4). This section considers some of the further roles partnerships can play to promote the SDGs, examining three global partnerships, three regional partnerships and one public-private partnership.

17.5.1 Global Partnerships

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) Sectoral Policies Department (SECTOR) promotes the ILO’s Decent Work Agenda to advance Target 8.8 on protecting labour rights and promoting safe and secure working environments.Footnote 1 The ILO’s promotion of decent work in forestry includes interventions to support the transition from the informal economy (e.g. illegal logging) to the formal economy, promoting employment creation, enhancing training and skills development and improving working conditions (ILO 2017). Together with FAO and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), the ILO formed the Joint Experts Network on Green Jobs in Forestry, which fosters international cooperation on the technical, economic and organisational aspects of forest management, working techniques and training forest workers. The network contributes to the integrated work programme of the Committee on Forests and the Forest Industry and the European Forestry Commission, in particular for green jobs in the forest sector and the social and cultural aspects of SFM (ILO 2018). Other organisations engaged in partnerships on forest workers’ rights and, more broadly, the rights of Indigenous peoples and forest communities include the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), especially through its Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy; the Forest Peoples Programme; the Centre for People and Forests; and the International Model Forest Network.

The Collaborative Partnership on Forests (CPF) is an interagency partnership among 14 international organisations (including IUFRO, CIFOR, ICRAF, GEF, FAO and IUCN). Among the SDG targets that the CPF contributes to are Target 17.6, on enhancing access to science, technology, innovation and knowledge sharing, and Target 17.8, on operationalising capacity-building mechanisms in science, technology and innovation. The CPF aims to streamline and align the work of member organisations and find ways to improve forest management (including conservation, production and trade of forest products). One of the most important initiatives of CPF member organisations, especially IUFRO, is the Global Forest Expert Panels, which serve as an international boundary mechanism that mediates the transfer of state-of-the-art knowledge across the science–policy interface. The knowledge these panels generate is disseminated at international forest policy bodies such as the World Forestry Congress and the UNFF and is widely accepted by the forest policy community as authoritative (Humphreys Reference Humphreys2009).The World Business Council for Sustainable Development has a Forest Solutions Group (FSG) that aims to provide a global platform for collaboration across value chains for forest products. The FSG’s emphasis on expanding markets for responsible forest products and sustainability performance (WBCSD 2018) contributes to SDG 12 on responsible production and consumption. Businesses signing up with the FSG agree to adhere to a set of membership responsibilities on sustainable development that are measured by key performance indicators, including resource efficiency and climate and water stewardship.

17.5.2 Regional Partnerships

Initiative 20x20 is the first regional commitment to at-scale forest and landscape restoration in Latin America. Participants include the WRI, International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE), IUCN and Natural Capital Project, organisations in national and regional governments and the private sector (WRI 2017a). Its work promotes Target 15.2 on ending deforestation and restoring degraded forests. The initiative has secured commitments from 11 countries, 3 states and 4 NGOs to restore 27.7 million ha of land by 2020, and has secured private investments of USD 1.15 billion (WRI 2017a). These commitments directly contribute to the SDGs and can generate co-benefits for people, economy and ecosystems. However, challenges exist in turning commitments into measurable restoration, particularly where there are limitations in institutional capacities, financial architectures and local participation. Efforts that rely on planting trees to achieve restoration goals are unlikely to result in vast expanses of reforested areas given the costs, time required, low survival rates of planted trees and forestry departments with limited resources (Reij and Winterbottom Reference Reij and Winterbottom2017).

The Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) is a partnership established in 1989 between 21 Pacific Rim economies. Among the forest-related SDGs to which APEC contributes is SDG 15.2 on increasing forest cover. In 2007 APEC adopted the 2020 Forest Cover Goal to restore 20 million ha of forests. The Sydney APEC Leaders’ Declaration on Climate Change, Energy Security and Clean Development includes the commitment ‘to achieve an APEC-wide aspirational goal of increasing forest cover in the region by at least 20 million ha of all types of forests by 2020’ (APFNet 2015). If achieved, this would store approximately 1.4 billion tonnes of carbon – about 11 per cent of annual global emissions. However, the goal, endorsed by all 21 APEC members, is voluntary, with no enforcement mechanisms to assure compliance. Since its adoption, planted forests have increased by slightly more than 20 million ha across APEC countries. However, the net increase of forest cover was only 15.4 million ha due to a 7.9 million ha decrease in forest cover in Indonesia, Peru and Australia (APFNet 2015).

The SAMOA Pathway is an initiative of small island developing states (SIDS). SAMOA stands for SIDS Accelerated Modalities of Action, a pathway approach to sustainable development with several priority areas pertaining to forest-related SDGs (SIDS 2014). The main sustainable development concern of the SAMOA Pathway is to build resilience to counter sea-level rise related to climate change (consistent with Target 13.1), a key priority for all low-lying atoll states. For the larger SIDS, such as Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, forests provide a revenue stream as well as non-economic benefits such as tourism. Regional organisations such as the Caribbean Community and the Pacific Islands Forum play an important role in information sharing and coordination. In December 2015, the General Assembly established the SIDS Partnership Framework, in accordance with the SAMOA Pathway, to monitor and ensure the implementation of pledges through partnerships for SIDS.

17.5.3 Public–Private Partnerships

The Global Partnership on Forest and Landscape Restoration (GPFLR) is an international network that brings together governments, research institutes, communities and individuals. Launched in 2003 by the IUCN, the WWF and the UK’s Forestry Commission, the partnership of 25 governments and NGOs aims to restore 350 million ha of deforested and degraded land by 2030 (GPFLR 2017). It aims to respond to the Bonn Challenge (consistent with Target 15.2) on restoring deforested land and degraded forests by promoting forest and landscape restoration (FLR), defined as ‘a process that aims to regain ecological functionality and enhance human well-being in deforested or degraded landscapes’ (Besseau et al. Reference Besseau, Graham and Christophersen2018). The focus of FLR is landscapes (rather than individual forest sites), with FLR taking place both within and across landscapes in order to create interacting land uses and management systems.

This brief survey makes clear some of the roles partnerships can play. In addition to raising and disbursing finance, roles include generating and disseminating scientific knowledge, pooling expertise, promoting innovative solutions (such as FLR), protecting workers’ rights and promoting sustainability practices among forest-related businesses in support of the SDGs. Local umbrella organisations play an essential role in forging partnerships for sustainable development. Local concerns can be channelled into global processes by organisations representing local groups and communities. Examples from Latin America include the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin and the Mesoamerican Alliance of People and Forests (AMPB). These organisations help ensure that delivery of the SDGs and related commitments is respectful of Indigenous peoples and local communities. For instance, AMPB organised local consultations through members to identify advocacy priorities in climate-change negotiations to inform their ‘If Not Us, Then Who?’ campaign, which called for the recognition of resource rights and FPIC. Community–company partnerships for timber and non-timber forest products, including partnerships for PES, can provide communities with income and other benefits. Although PES is often presented as a win–win scenario that raises additional finance for sustainable development, contributes to conservation goals and enables land-based poor groups to benefit from additional income (Duncan Reference Duncan2006, Pagiola et al. Reference Pagiola, Arcenas and Platais2005, Wunder Reference Wunder2008), care must be taken to ensure respect for the rights and ancestral lifestyles of Indigenous peoples.

Different partnerships can generate different outcomes. Foreign direct investment from a multinational logging company will bring short-term gain to an indebted economy that relies on export earnings. Yet the communities most impacted by logging often see little of the market value of timber production while bearing the socio-economic and environmental costs. This underlines an inherent tension in the dynamics of partnerships: relationships tend to be asymmetrical, with a clear hierarchy of power and influence. In the context of the tropical timber trade such relationships operate between local landowners and national governments, which, in turn, are connected to the power dynamics between the more developed ‘core’ economies and those that trade with them. This dynamic is overlaid, and often reinforced, by the private sector, with many multinational corporations aiming to maximise profit extraction while social and environmental costs are often borne by local communities. We now turn to the question of asymmetrical power relationships in the global economy.

17.6 The Broader Structure of Economic Governance

If it is to be comprehensive, the discussion in this chapter on strengthening the means of implementation and revitalising partnerships for sustainable development cannot focus solely on forests and forest-related sectors. With Target 17.13 stressing the need to enhance macroeconomic stability, including policy coordination and coherence, and Target 17.14 emphasising the importance of policy coherence for sustainable development, the broader political and economic context within which efforts to promote sustainable development occur must be considered.

Here an international political economy framework is helpful. For international political economists, understanding global power structures requires comprehension of both politics and economics. Those who wield economic power, such as business executives and financial elites, must take into account political factors, such as government policy, while the exercise of political power is shaped to a large degree by the economic context. Hence, there is a complex and iterative relationship between political and economic power.

Contrary to what SDG 17 aims to promote – a global partnership for sustainable development – a political economy view argues that in as much as a global partnership may be said to exist, it is one founded on neoliberal principles, such as the expansion of international trade and economic growth, with relatively limited attention to environmental conservation. In this view, the triumvirate of international economic and financial institutions – the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organisation – provide a neoliberal normative framework that favours the interests of transnational corporations and powerful states, primarily from the Global North (Humphreys Reference Humphreys2006). This framework promotes the liberalisation of goods and services and the restructuring of economies in the Global South to enforce the repayment of debts. This can be seen as a neoliberal business-based constitutionalism in which corporate rights and capitalist expansion dominate at the expense of the environment and human welfare (Gill Reference Gill2002, Derber Reference Derber2002).

According to this view, the pursuit of sustainable development cannot succeed because the normal and routine functioning of the global economy generate unsustainability, negating any gains that may be realised through the promotion of the SDGs. For example, in 2012 (the most recent year with reliable data) developing countries received about USD 2 trillion in ODA, foreign investment and trade. However, for this same year, some USD 5 trillion flowed from developing countries to the Global North in the form of debt repayments, capital flight, repatriation of profits, payment of intellectual property rights and illicit outflows (Hickel Reference Hickel2017). In other words, the poorer countries of the global economy made a net transfer of approximately USD 3 trillion to the richer countries. According to another estimate, in 2012 the governments of developing countries repaid USD 182 billion to their creditors but received only USD 133 billion in ODA. Remittances from emigrants grossed an estimated USD 350 million, while multinational corporations made about USD 678 billion in profits, most of which was repatriated to their headquarters in developed countries (Gottiniaux et al. Reference Gottiniaux, Munevar, Sanabria and Toussaint2015). According to Global Financial Integrity (GFI), the cumulative total of net South-to-North financial transfers since 1980 is USD 26.5 trillion (GFI 2015, Hickel Reference Hickel2017). These figures illustrate the exacerbation of a problem that SDG 10 seeks to address: reducing income inequalities between countries.

Debt servicing ratios as a percentage of exports of goods and services are once again trending upward, indicating extra pressure on forests and other natural-resource sectors to increase exports to earn hard currency to service external debts. From 2000 to 2011, debt service fell from 12.9 per cent to 3.6 per cent in lower-middle-income countries before increasing to 6.1 per cent in 2015 (UN 2017, UN 2016), a trend that runs counter to Target 17.4 to assist developing countries attain long-term debt sustainability. Although African countries annually receive USD 161.6 billion inflow through loans, remittances and aid, they incur net losses of about USD 203 billion through trade misinvoicing, debt payments and resource extraction (Curtis and Jones Reference Curtis and Jones2017). Donoso Game (Reference Donoso Game and Delen2018) estimates that between 1990 and 2004 Latin America paid USD 1.9 trillion in debt services (i.e. about USD 126.9 billion per year).

Llistar Bosch (Reference Llistar Bosch2009) coins the term transnational interference to denote interventions from outside a country that directly or indirectly affect the internal dynamics of a social group, community or country. These interferences take the form of normative transmissions through transnational mechanisms, such as loan agreements and sovereign debt-repayment schemes that impose conditions on developing countries. Not all transnational interferences are negative. International cooperation that promotes SFM or that addresses illegal logging are examples of positive transnational interference. For Llistar Bosch (Reference Llistar Bosch2009), however, most transnational interference is negative: economic support to developing countries is influenced by geopolitical realities that correspond more to donor interests than those of the beneficiaries.

As well as focusing on legal flows of finance and natural resources, it is also necessary to examine those that take place illegally. It is estimated that, since 1980, illicit outflows account for 82 per cent of South-to-North net resource transfers (GFI 2015). Hickel contrasts the GFI estimates with more cautious OECD ones: ‘there is general consensus that illicit financial flows likely exceed aid flows and investment in volume’ (OECD 2014b: 15, cited in Hickel Reference Hickel2017: 334). These illicit financial flows include criminal activities in the logging sector, resulting in revenue losses that could be reinvested in forests. The World Bank has estimated that as much as 10 per cent of the value of the global timber trade is from illegal sources (World Bank 2006), with the figure for some countries as high as 90 per cent (Pereira Goncalves et al. Reference Pereira Goncalves, Panjer, Greenberg and Magrath2012). The World Bank has also estimated that the global loss of revenue from illegal logging is at least USD 10 billion annually, about eight times greater than the total ODA flows to forests (World Bank 2013) and possibly as high as USD 15 billion (Pereira Goncalves et al. Reference Pereira Goncalves, Panjer, Greenberg and Magrath2012). According to GFI, USD 1.09 trillion flowed illegally from developing countries in 2013, compared to USD 465.3 billion in 2004 (Kar and Spanjers Reference Kar and Spanjers2015). Research from UNCTAD reveals that the widespread illicit practice of trade misinvoicing – the practice of deliberately misreporting the value of imports or exports on invoices to enable capital flight, usually to an offshore account – is weakening the capacity of developing countries to implement sustainable development. This problem is widespread in primary commodity sectors in many developing countries (UNCTAD 2016). Between 1980 and 2012, developing countries lost USD 13.4 trillion through leakages in the balance of payments and trade misinvoicing (Centre for Applied Research 2015). Trade misinvoicing is an important route for capital flight from timber industries in many countries, including Cameroon (Mpenya et al. Reference Mpenya, Metseyem and Epo2016). Countering illegal logging and other forest-related crimes relates to Target 16.4 to ‘significantly reduce illicit financial and arms flows, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets and combat all forms of organised crime’. However, progress towards achieving this target is mixed.

17.7 Conclusions

The evidence assembled in this chapter provides reason for cautious optimism on SDG 17. Significant progress has been made in generating additional funding for implementing forest-related sustainable development, with funding for forests from ODA and other sources trending upward. However, while a focus on increasing SDG implementation may lead to some tangible gains for forests, it may simultaneously reinforce some potential contradictions among SDGs. For example, much forest finance, in particular REDD+, has been targeted at the carbon sink function of forests. While this helps to attain SDG 13 (Climate Action), without strong safeguards for other forest goods and services it may run counter to realising SDG 15 (Life on Land). A further example includes the relationship between agriculture and forests. In several countries, international forest-related ODA is dwarfed by domestic subsidies for agricultural production. This provides a structural incentive for the conversion of forests to agricultural land, in particular for the four forest-risk commodities. Both these examples suggest that realising forest-related sustainable development depends on policy coherence between the forest sector and forest-related SDGs, as well as addressing the complex conflicts and synergies between them. While strengthening the means of implementation is to be welcomed, it should not be seen as a panacea. It can only lead to SFM when the intersectoral causes and consequences are fully understood, so that the broad range of public and private goods forests provide are conserved.The case of ZND illustrates the importance of the duality of SDG 17, which promotes strengthening the means of implementation and revitalising partnerships for sustainable development. New partnerships can help generate additional finance, yet if finance is to be spent in ways that enhance SFM, then cross-sectoral partnerships extending beyond forests and promoting integrated strategies are necessary. Only with such partnerships can the synergies and trade-offs among SDGs and the implementation of SFM be effectively addressed. However, such efforts are a work in progress, and there is a need to pay more attention to the promotion of finance and investments for sustainable land use, particularly sustainable agriculture and livestock. Here, impact investment may make a positive contribution. The underlying logic of impact investment is that there is a positive-sum game among carefully targeted investments that generate added value in terms of both sustainability and profits for investors. Where there is a need from a sustainability standpoint but no prospect of returns for investors, then the need must be met from national or international public finance.

Evidence has been presented which suggests that a focus solely on the SDGs is insufficient when contemporary global economic governance, including forest-related crimes, negates the gains from the sustainability agenda. It is argued that efforts to strengthen the means of implementation and forge innovative partnerships are taking place within a global economic system governed by neoliberal principles rather than the principles of conservation or sustainability. Major constraints to sustainable development lie in deep-rooted structures and practices that continue to generate and reinforce unsustainable practices in forestry and other extractive industries, with widening inequalities and power disparities severely curtailing the ability of governments and other actors to pursue sustainability.

The dominant global political agenda remains focused on economic growth and the liberalisation of trade and investment rather than conservation and sustainable development. We therefore finish on a cautionary note: a focus on just forest-related financial flows and forest-related partnerships misses the bigger picture. Financing for sustainable development is negated by net South-to-North financial flows and vast inequalities of power that undermine the capacity of many countries to conserve the ecological life-support functions on which present and future generations depend. Achieving genuinely durable and long-term sustainability requires turning our attention to the environmentally degrading effects of the broader structures of economic governance.