This article aims to understand transnationalism as a process, in terms of individuals’ and groups’ agency, from the point of view of the actors and their ways of thinking and acting. It focuses on the subjective experience of nationality and (trans)national belonging based on biographical interviews with two groups of Jewish participants born in Bulgaria before World War II. Some of them have spent their lives in Bulgaria and still reside there. Others moved with their families to the newly established state of Israel in a mass exodus in 1948–1949. To capture the actors’ perspective, I employ a grounded theory approach allowing the themes to emerge from the narratives. Following them, I zoom in first on the decision-making (to emigrate or not) and then on the transnational ties and activities that have nourished a sense of (trans)national belonging. I am interested in how “ordinary” people construct nationality through their life stories and how they make “biographical sense of transnational ties” (Boccagni Reference Boccagni2012, 41). Thus, I focus on subjectivity and negotiation of shared meanings or on what has been defined as vernacular memory (Gluck Reference Gluck, Jager and Mitter2007; Breuer Reference Breuer, Bond and Rapson2014; Koleva Reference Koleva2022). I build on my previous research on the interplay of biographical and collective memory, following the tradition of the early Halbwachs (Reference Halbwachs1952), with family, ethnic minority group, and generation as the mnemonic communities framing personal memory (Koleva Reference Koleva2009; Reference Koleva2016).

This approach defines the empirical and “bottom-up” nature of the study. While the case at hand can be related to a wealth of theorizing on migration, minorities, nation-building, and the Cold War and its aftermath, I prefer here to preserve – insofar as possible – the voices of the participants, to focus on their remembered (and reflected upon) experiences, and to understand how these relate to “the broader contours of influential narratives of events, of nations” (Radstone Reference Radstone2005, 139). The case under scrutiny offers a chance to refer to wider frames of memory, set by national contexts. Viewing nations as invented or “imagined” communities (Anderson Reference Anderson1983; Gellner Reference Gellner1983; Hobsbawm and Ranger Reference Hobsbawm and Ranger1986) implies viewing them also as “narrations” (Bhabha Reference Bhabha1990) – that is, as communities forged by storytelling, where national narratives function as “discursive devices that combine history, collective memory, and myth into teleological communications” (Anderson Reference Anderson2017, 4). Most often, research informed by these ideas has zoomed in on how such discursive devices, or “cultural tools” (Wertsch), have been constructed and wielded by national establishments (for example, Wertsch Reference Wertsch2002; Reference Wertsch2008). In contrast, this article asks how the social frames of memory have been appropriated, negotiated, and perhaps transformed in the everyday lives of the citizens. And more specifically: what happens when the narrative of the nation does not provide unproblematic foundations of personal and group identities, as is the case with minorities and migrants? I argue that national belonging in the case at hand is constructed in quasi-familial terms equating the Jewish minority in Bulgaria and the “Bulgarian” Israelis with a kind of extended family based on horizontal ties, generational continuity, and feelings of loyalty. The “family” trope simplifies “the complexity of nations” (Lauenstein et al. Reference Lauenstein, Murer, Boos and Reicher2015, 314), making “the nation” graspable and rationalizing the belonging to different and overlapping collectivities, defined by kinship, ethnicity, and residence.

Context and Methodology

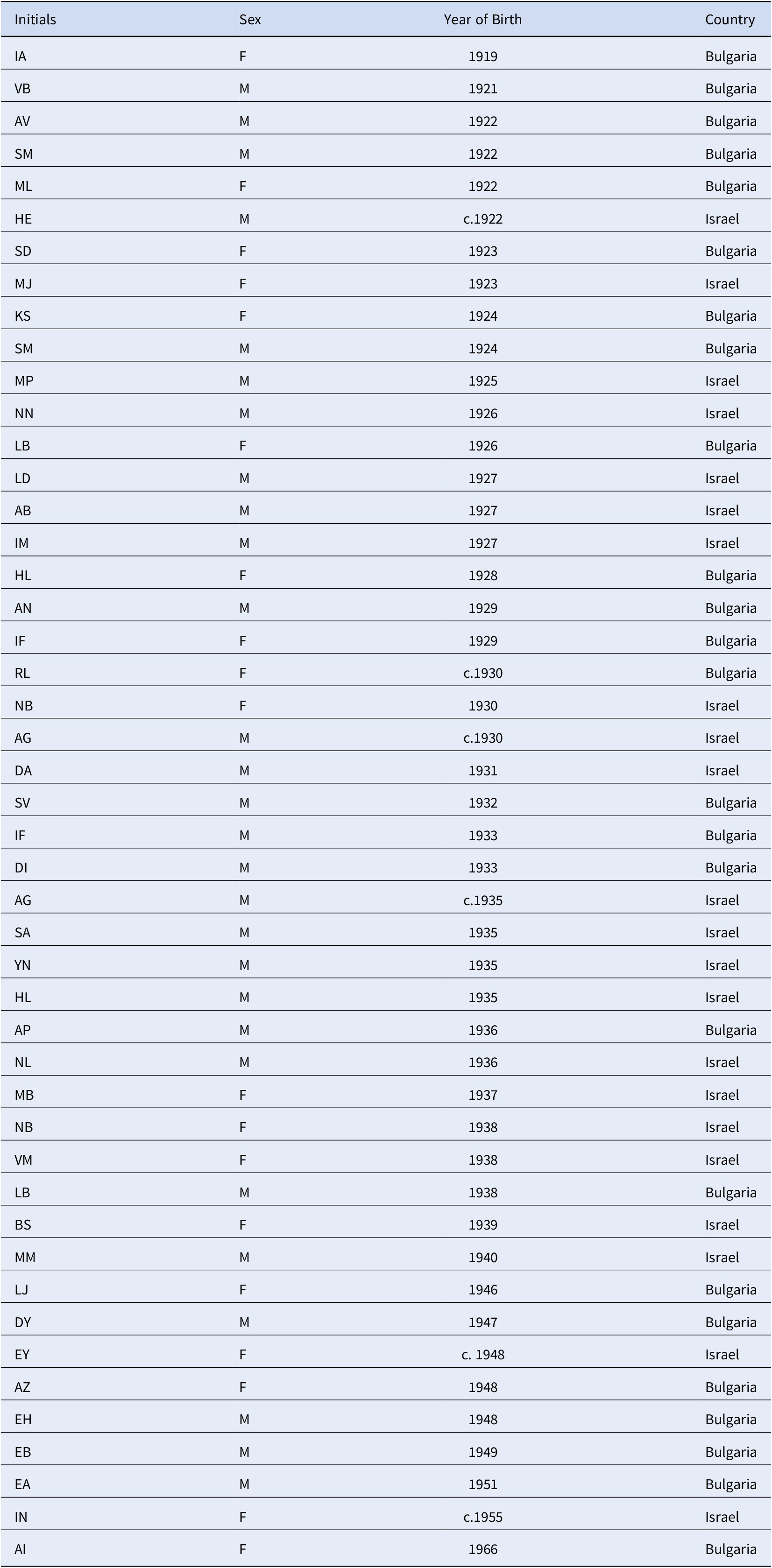

Combining the methodology of oral history with a comparative and transnational approach, the article revisits a project implemented in 2015 by the Institute for the Study of the Recent Past, Sofia. Its aim was to compile an oral history archive reflecting the life experiences of several social groups under the communist regime. The interviews followed a biographical approach, giving considerable freedom to the participants to choose their main topics. The Jewish participants focused most often on the repressions under the antisemitic Bulgarian legislation in 1941–1944; the emigration to Israel in late 1940s and the maintenance of transnational family and kinship ties thereafter; and the integration in the respective society and the changes since 1989. A total of 40 interviews were recorded, most of them with persons born before WWII, recruited through snowball sampling. Several interviews were carried with representatives of the next generation, in some cases – the adult children of the older interviewees. In Bulgaria, 19 interviews were with members of the first generation and 7 with those from the younger generation. In Israel, 9 individual interviews were carried out, 2 interviews with family couples, all in Tel Aviv-Yaffo, and 1 group interview with 7 men and 1 woman at a pensioners’ club in Bat Yam. There were also 2 younger women who were interviewed. All participants spoke Bulgarian. This article is based primarily on the interviews with the older generation who spent (at least) their childhood in Bulgaria and have personal memories of the mass emigration (Aliyah) in 1948–1949. Thus, they can be considered to belong to the same generation, impacted by the same “formative events” (Mannheim): WWII, the Holocaust, and the subsequent emigration.

The life narratives allowed for the possibility to go beyond the schematism of economically conceived push-pull factors and to gain a deeper understanding of aspirations that led to migrant decision-making, including the role of emotions and of culturally shaped imaginaries, personal, or group dispositions, and social pressures. When giving such accounts of their past, the participants “construct[ed] communities and locate[ed] themselves socially, temporally and spatially” (Komulainen Reference Komulainen2003, 66). Thus, it was possible to trace the role of social capital, transnational social networks, and cultural contexts also after the migration. Moreover, “deep stories” of the respective societies were revealed: not only how the participants constructed a vindicated identity drawing on available rhetorical resources, but also how their personal stories correlated with the respective national metanarratives in the two countries, how “the personal (family) and the historical (national) collective experiences are intertwined in a way which one lends sense to the other and vice versa” (Nowicka Reference Nowicka2020, 6).

As a collaborative and dialogical endeavor, oral-history interviewing engages the participants in “a three-way conversation: the interviewee engages in a conversation with his or herself, with the interviewer and with culture” (Abrams Reference Lynn2016, 76). In relation to the first aspect, the participants were asked to tell their life stories – that is, to engage in retrospective accounts, which are put together from the point of view of the present. As regards the second aspect, the interviewers’ ethnicity (Bulgarian)Footnote 1 and their much younger age must have influenced the choice of tellable stories and the way to tell them, highlighting aspects of multiculturality and ethnic tolerance, while probably subduing stories of discrimination.Footnote 2 Finally, the cultural framing of the stories, or “the workings of the cultural circuit” (Abrams Reference Lynn2016, 69), could be brought to the fore due to the clearly comparable life circumstances. Persons of roughly the same age faced the same choices at the same moment: to emigrate or not; then they faced the same challenges: to integrate into the respective society; and they ended up in the same existential situation: to keep kinship ties not just across borders, but also across the Iron Curtain.

In what follows, I will first outline the historical background and the post-1989 situation of the Bulgarian Jewry. Then I will describe the Aliyah of 1948–1949, as pictured in the reminiscences of those who emigrated and those who stayed behind, focusing on their motivations and their retrospective appraisals. Next, I will discuss the family and kinship relations across the Iron Curtain, where, in addition to the interviewees’ accounts, I rely on state-security archives. I shall briefly touch on the integration into the respective national society, including the erasure of Jewish identity imposed by the communist regime in Bulgaria and the containment of Sephardic identity in the Ashkenazi-led nation formation processes in Israel. Finally, I will try to unpack the participants’ positioning themselves as a transnational generation in their respective national contexts in the second half of the 20th century. Finally, I will point to possible broader implications that can be inferred from this specific case.

Historical Background and Present Situation

Bulgarian Jews are in their majority of Sephardic origin. They settled in the Ottoman Empire after their expulsion from Spain in 1492. According to the 1934 census, the last one before WWII, their number was 48,398 or 0.8% of the total population of Bulgaria (Istoria… 2012, 588). They were urban dwellers making their living as craftsmen, workers, and petty shopkeepers. Almost half of them lived in Sofia, with substantial Jewish communities in Plovdiv, Pazardzhik, Ruse, Shumen, Vidin, and Kyustendil. According to the multivolume academic History of Bulgaria, their small number and relatively low economic and social status explained the strong influence of Zionism in Bulgaria (Ibid.).

As an ally of Nazi Germany from March 1941 to September 1944, Bulgaria adopted harsh antisemitic legislation, which led to tragic consequences for the Balkan Jewry (Danova and Avramov Reference Danova and Avramov2013). The Nation Protection Act (1941) imposed an array of repressive measures on the Jewish population: they were deprived of voting rights, subject to curfew, excluded from jobs in the public sector; their economic activities were curtailed, and their access to university education was restricted. Following German attacks on Greece and Yugoslavia, the Bulgarian army occupied large parts of Vardar Macedonia (today’s Republic of North Macedonia) and Aegean Thrace (northern Greece). An agreement was signed with Nazi Germany in early 1943 to deport 20,000 Jews to the death camps of the Third Reich. These were to comprise 12,000 from the “new territories” and 8,000 from “old Bulgaria.” The deportation was regarded as the first step toward “the final solution,” to be followed by that of the rest of the Jewish population of Bulgaria. In March 1943, 11,343 Jews from Vardar Macedonia, Aegean Thrace, and the Pirot region (Eastern Serbia) were transported to Treblinka. In the “old territories,” however, a campaign in defense of the Jewish neighbors started, initiated by intellectuals, oppositional politicians, and the higher ranks of the Orthodox clergy (Kohen Reference Kohen1995), and involving the Vice-Chair of the Parliament Dimitar Peshev and 42 MPs from the ruling majority. As a result, the Jewish population of the “old territories” avoided deportation and, unlike that of other Eastern European countries, faced the experience of mass emigration in the wake of the war. Trickles of Jewish emigrants had flowed from the Balkans to Palestine already earlier, as a result of the homogenizing pressure on minorities within the newly established nation states (Benbassa and Rodrigue Reference Benbassa and Rodrigue2000, xxiii). But the size of the post-WWII Jewish emigration from Bulgaria is probably only comparable to that from Turkey (Toktaș Reference Toktaș2006; Bali Reference Bali2011). Still, while the numbers were similar, the emigrants from Turkey represented c. 40% of its Jewish population, while for Bulgaria in 1948–1956, the share was over 85%.

Two tendencies developed in parallel among the Bulgarian Jewry in the aftermath of WWII: one of integration into the post-war Bulgarian society as a “model minority,” and one of emigration to Palestine/Israel. They generated tensions within the Jewish communities in the first years after the war (Shealtiel Reference Shealtiel2008, 339–346, 446–449). While most of the Jewish institutions were taken over by communists (Shealtiel Reference Shealtiel2008, 322–328), the Zionist movement remained influential. The communist-dominated government of Bulgaria announced its support for the emigration to Palestine already in 1946–1947, although it did nothing to facilitate it.Footnote 3 The UN decision on the establishment of the State of Israel and in particular the Soviet support for it (Gromyko Reference Gromyko1947) played a favorable role for the reconciliation of the desire for emigration and the leftist/communist orientations among Bulgarian Jewry. Moreover, in July 1948, the Central Committee of the ruling communist party finally decided to assist the emigration. Between October 1948 and May 1949, 32,106 Bulgarian Jews emigrated to Israel in an organized way (Vassileva Reference Vassileva1992, 123–124). Their numbers in Bulgaria went on diminishing, reaching 6,431 persons in 1956 (Vassileva Reference Vassileva1992, 147; Shealtiel Reference Shealtiel2008, 493).

As a result of the thorough expropriation of businesses and properties in the late 1940s, the traditional Jewish occupations – petty trade and crafts – were disintegrated. The role of the Jewish Consistory boiled down to that of a cultural institution under communist control. Local Jewish communities withered away. Most often, their properties were transferred to the Bulgarian state. Private homes were sold out or left to the care of relatives or attorneys. Emigrants were deprived of Bulgarian citizenship. Because Bulgaria and Israel were on the opposite sides of the Iron Curtain, back-and-forth movement was not easy. Unlike Turkey, return migration was next to impossible. The situation was aggravated after the Six-Day War in 1967, when diplomatic relations between Israel and Bulgaria were severed and a tacit antisemitism established itself in Bulgarian institutions, especially the ideologically important ones, such as the media, the army, and the police.

With the demise of the communist regime, Bulgarian Jewry experienced a cultural revival. Urban Jewish properties were restored. Certain forms of community life were reinstituted and new ones were established, targeting both youth and adults. For those who grew up in communist Bulgaria, this was in many ways a veritable encounter with the tradition of their ancestors. International Jewish organizations sponsored a Jewish school in Sofia and extramural courses in Hebrew. It became possible to study the traditional Sephardi language Ladino/Judesmo as well.Footnote 4 With the liberalization of publishing in the 1990s, an avalanche of publications for and from the community appeared. Contacts with kin in Israel intensified, travel between the two countries became easy. After decades of ethnic homogenization, the pendulum swung toward re-ethnification and re-invention of Jewishness.

While significant research has been done on Jews in Bulgaria (see Eskenazi and Krispin Reference Eskenazi and Krispin2002 for a bibliography) and on their situation during WWII (Avramov Reference Avramov2012; Dadova-Mihailova Reference Dadova-Mihailova2011; Danova and Avranov Reference Danova and Avramov2013; Hadjiiski Reference Hadjiiski2004; Kohen Reference Kohen1995; Paunovski and Ilel Reference Paunovski and Ilel2000; Poppetrov Reference Poppetrov2011; Ragaru Reference Ragaru2017; Todorov and Poppetrov Reference Todorov and Poppetrov2013; Toshkova et al. Reference Toshkova1992; Reference Toshkova, Koleva, Kohen, Gezenko, Taneva, Ditchev and Hadjiiski2007; Troebst Reference Troebst2011), the post-war emigration to Israel (Aliyah) has received scant research attention (Vassileva Reference Vassileva1992; partly Haskell Reference Haskell1994; Shealtiel Reference Shealtiel2008) – and its aftermath, even less so (partly Grozev and Marinova-Hristidi Reference Grozev and Marinova-Hristidi2013).

The Great Aliyah as Experience

My particular interest here is how the Aliyah was experienced and is remembered by those who participated in it and by those who did not. The aim is to tap into subjective experiences and their retrospective interpretations, and to contemplate how the latter might have been framed by the memory cultures in Bulgaria and Israel.

All interviewees, both in Israel and in Bulgaria, defined the communist-led coup d’état on September 9, 1944, and the coming of the Soviet Army, as “liberation,” using the pre-1989 cliché. With only one exception, they kept the focus of their narratives on how their own situation, as Jews, had improved, and they did not comment on the terror during the first weeks and months of the new regime. They were reluctant to dwell on the tensions among the Bulgarian Jewry after WWII, generated by the two ideologies – communism and Zionism – and the ensuing attitudes toward emigration.

Predictably, the migrants had many stories about their Aliyah and relished telling them. They usually gave the exact date of their arrival to Israel and the name of the ship; they described their itinerary in abundant detail, and they enumerated items that they brought or could not bring with them. It is likely that these stories have repeatedly been told and re-told to peers, children, and grandchildren. In particular, the group interview at the pensioners’ club, where each speaker had their story immediately verified by the others, suggests the existence of a vernacular public sphere, which has supported memories of this kind. Conversations with the participants indicated that such memories could sometimes be shared beyond informal circles (published, screened on TV). In any case, they did not question or contradict dominant public narratives; rather, they used tropes borrowed from the latter.

The interviewees rarely spoke about their feelings and state of mind when leaving Bulgaria. Nor were there spontaneous narratives about their motives and how the decision to emigrate was made. They spoke about these only in response to my questions, which leads to the hypothesis that my interlocutors considered it normal, self-evident, understandable to have moved to Israel and did not see a need to explain this decision. They often compared the spread of the idea of emigration to a virus:

-

– It was a disease! It was a disease! In fact, when we married [March 1948], we had no intention of… and then it started – the paper! – who will get the paper that he is accepted and will leave first, with the first ship for Israel. We used to say “la belezhkita,”Footnote 5 it means, the paper. Who will get the paper! That was the best of luck – to get the paper to be able to leave. Impatient. Especially the young people. (Mr. MP, first generation, Israel)

-

– It was a mass, mass decision of all Jews, of most of us. Those who were partisans, communists, they stayed in Bulgaria. But most of us, we left en masse. It was like an infection – from the one to the other, from the one to the other – everybody wanted to leave. Not knowing where he was heading for. (Mr. LL, first generation, Israel)

-

– And when my father said “we’re leaving for Israel” – [I asked] “Why?” – “Everybody is leaving.” But it was not like we ran away from something. (Ms. MB, first generation, Israel)

-

– She didn’t even finish high school, this cousin of mine. She got infected with that Zionist propaganda, which was conducted among young people. (Ms. KS, first generation, Bulgaria)

These statements seem to run counter to the assumptions of informed subjects making rational choices, which underlie many theories of migration and which are fully applicable to the 1990s emigration wave.Footnote 6 The metaphors of “disease,” “infection,” “contagion,” and “fever” come close to those used by contemporaries and researchers to describe other, earlier migrations (Siegelbaum Reference Siegelbaum2017). Their semantics captures both the excitement expressed retrospectively by the interviewees and the diffusion of the idea through personal transmission within tight-knit communities. At the same time, the connotation of “fever” and “contagion” seems to bypass the question of personal choice and responsibility representing the process as a quasi-natural one. Thus the fever-narratives demonstrate the power of external factors, such as group interaction, which “translate into… motivational capacity” (Czaika, Bijak, and Prike Reference Czaika, Bijak and Prike2021, 18).

Still, many interviewees stressed the role of the Zionist youth organizations, especially Hashomer Hatzair,Footnote 7 the most influential one in Bulgaria.

-

– All these young people, who were organized in Jewish organizations, they were mentally ready for this, to come to Israel. To come illegally. Because they were Zionists. And in Bulgaria, they were given the opportunity to function. Even though they were Bulgarians, they were Zionists as well. (Mr. IM, first generation, Israel);

-

– My brother, he didn’t ask permission and he left. Then, I was in Hashomer Hatzair, all the time I wanted to leave, of course, but they wouldn’t let me, no chance. When they started to allow [emigration] in 1948, they started to issue certificates, it became possible to leave – then I told them [his parents] that if they don’t let me go, I’ll run away. (Mr. YN, first generation, Israel);

-

– He [her father] used to say, our party is Zionist-communist. … He was a great Zionist. He wanted, already as a high-school student, to flee from Bulgaria and to come here. (Ms. BL, first generation, Israel)

-

– We were then soldiers – of Zionism (Mr. MM, first generation, Israel).

-

– (Weren’t you afraid?) I’d say, in such a thing, after 2,000 years, the fear somehow withdraws. (Mr. NN, first generation, Israel)

According to these statements, Zionism seems to have evolved in post-war Bulgaria from a system of ideas consolidating ethno-national identity into an existential goal, and from a political program into a life politics. As shown in the quotes above, the Zionist myth-history decrying diaspora life and calling for return/ascendance to the ancient fatherland was taken literally. Indeed, many members of Hashomer Hatzair generally perceived no contradiction with communism in spite of their national-ideological priorities: they saw the realization of their goals in two steps: first establishing a Jewish state, and second, transforming it into a socialist society (cf. Cohen Reference Cohen2000, 64). Hence, the frequent statement of the Israeli interviewees that Jewish communists were Zionists at the same time.

It is also likely, as some researchers have hypothesized, that survivors of WWII might have embraced Zionism “as an ‘intuitive’ response to war-time persecution,” offering “a sense of collective identity, hope, and future” (Yehudai Reference Yehudai2014, 75). Some interviewees also maintained that emigration was triggered by the war experiences and the fear that this might happen again:

-

– After the 9th September [1944] we learned in detail what had happened in Auschwitz, Dahau, Treblinka, and we were shocked. And when in 1948 it became known that a Jewish state was being founded, the Jews said: “But we must indeed have a state of our own, we must go there.” (Mr. AP, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– The thought lingered that Bulgaria must be abandoned since all that had happened in the camps, and that had been a total destruction, provoked the danger that it could happen again. (Ms. HL, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– The fear experienced during Nazism quickly led people to believe that if they gather in one state only Jews, … they would be protected, life would be different… That is why Jews quickly got contagion from each other. And they submitted their papers, they got their free tickets and they left. (Mr. IF, first generation, Bulgaria)

These explanations are in line with the more widespread opinion about Central-European Jewish diaspora: that they chose to emigrate because of their experiences of the Holocaust. Bulgarian Jews, in general, did not have a direct experience of this kind, although many were actually rounded up in schools in March 1943 before the deportation order was cancelled. Two points merit attention here. Firstly, their own experience, what they personally went through – wearing yellow stars, curfew, internment, ban from school or university, bankruptcy – were not mentioned as grounds for fear and reasons for emigration but the experience of the other European Jews, which has been established in the globalized memory of the Holocaust as a paradigm of suffering. Secondly, this motivation was pointed out only by interviewees who stayed in Bulgaria. None of the Israeli interlocutors ever mentioned it – a circumstance that invites a consideration of the memory cultures in the two countries.

Though less often than Zionism, the interviewees pointed to disappointment with the political course Bulgaria took after WWII as a motive for emigration. One reason, as they saw it, was that the thorough expropriation deprived petty craftsmen and shopkeepers of their means of subsistence. This reason was given more often by participants in Israel:

-

– I think that communism was the reason. Not all Jews could adapt. Few people used to like it. (Ms. MJ, first generation, Israel);

-

– My brother left… He saw what course things were taking, and he was a free mind, and how would he obey some such… forget it! And he left. I think that the greatest part of those who left, they couldn’t find their place in an already different way of exercising an occupation. You could no longer be a trader, an owner… The decision was strongly influenced by the deadlock that was here. (Ms. HL, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– We didn’t know yet what was approaching us… Only when we saw Dobri Terpeshev’s self-criticism, the charges against Anton Yugov… So we started to feel what was approaching us. And then, emissaries from Israel came and said: Give up communism, run away, come to Israel, no, Palestine! (Mr. IM, first generation, Israel)

-

– Everyone thought already how to leave Bulgaria. Because most of them were not so happy that the government was… They got kicked out of here, kicked out of there… I don’t know. (Ms. NB, first generation, Israel)

While there are other testimonies of the post-war enthusiasm and later disappointment among the Bulgarian Jewry,Footnote 8 it is worth noting that in the interviews, these opinions were coupled with critical views on the communist regime in Bulgaria, while in other contexts, the interviewees refrained from expressing their attitudes to the regime. Given the overall tendency among migrants to emphasize the “pull” factors (Amit and Bar-Lev Reference Amit and Bar-Lev2016, 112), these utterances are very significant. Some of them (especially the last two quotes above) point to the antisemitism in communist Bulgaria. The interviewees might have felt uneasy to expand on this issue, given that the interviewers were ethnic Bulgarians, albeit from a younger generation. Clearly, the disappointment with the regime was in some cases caused by the ongoing discrimination, rather than the course toward Sovietization.

One interviewee, the widow of a famous Tel Aviv doctor and sister of a renowned professor of oncology, hinted at the desire for freedom and self-fulfillment:

-

– My brother and my husband studied [medicine]… They did not complete the last semester of their fifth year, they decided to come to Israel. They did not want to stay there [in communist Bulgaria] as young doctors, they wanted to see a larger world. (Ms. MJ, first generation, Israel)

This is the only case when one’s own striving for personal and professional fulfilment was mentioned as motive to emigrate. It can be hypothesized that narratives of self-fulfillment could not easily find support in the public sphere of the early state of Israel, which demanded permanent mobilization of its citizens and attendance to their duties rather than catering for their personal fulfilment. This statement can thus be seen as part of the interviewee’s fascinating story of how medical education and medical care were set up in the new country by that very generation of young doctors, to which her kin belonged.

While the influence of Zionism and the discontent with the post-war situation in Bulgaria could be easily predicted, a strong generational motive is to be found in the life stories as well. Migration is not only proven to have been a family strategy, but its dependence on the embeddedness in social networks outside the family is also highlighted (cf. Haug Reference Haug2008). Families are seen not as homogeneous units but through the lens of their generational composition. All interviewees testified that the younger members of their families (they themselves or their siblings) took the initiative for emigration. This can be explained with the influence of the Jewish youth organizations, as well as the preferences on the Israeli side for young settlers. The interviewees, however, stressed the unique situation from the point of view of intergenerational relations in mostly traditional families:

-

– We were the forerunners. They [parents] followed us. (Mr. IM, first generation, Israel);

-

– We brought our parents here, they didn’t even know where they were going, but they followed us. (Mr. HE, first generation, Israel);

-

– My mother was a communist; she didn’t want to come at all. They were already going to divorce… One day, my brother came and said: “You, mother, can decide that you want to stay, you want to divorce – I am not going to teach you what to do, but I am off to Israel” – 13 years old! – “with the organization, with my friends, we are going to a kibbutz.” My mother, when she heard this, she wouldn’t part from her children. She bent her head down, they packed and they set for Israel. This was the reason, that my brother gave her an ultimatum. (Ms. BS, first generation, Israel);

-

– (And your parents, did they intend to emigrate?) My father no, my mother yes. She was a very clever woman and she understood that the right place of the family was to be together. (Mr. YN, first generation, Israel);

-

– We came here in March 1949. My brother came in April and my mom said to my father: “My life is worth nothing without my children. I will not be able to make it. I want to be where they are!” – and my father agreed. And they came a month later. They locked the house again, they left everything. (Ms. MJ, first generation, Israel)

Thus, the interviewees not only underlined their agency as young people but demonstrated how traditional family solidarity had worked in a non-traditional way, reversing the authority of the older generations. At the same time, they also made clear how different generations had their own particular way of interpreting the historical moment, and how youths got empowered in the inter-generational relations in their families, their biographical calendar being more synchronous with the historical situation. This, however, is true not only of those who left but often also of those who stayed: there are a few stories of youngsters who refused to follow their parents in emigration. In some cases, this led to the division of the family, and in others to a decision of the whole family to remain in Bulgaria.

Staying in Bulgaria

The interviewees who stayed in Bulgaria told different stories. Emigration was not a prominent topic in their recollections. They talked about it when prompted by the interviewer, and they mainly gave reasons why they did not emigrate. This circumstance, again, evokes the hypothesis that emigration used to be considered the “normal” life choice, while non-migration had to be explained.

Non-migrants did not use the term Aliyah. Interestingly, the verb they most often used, izseliha se (they left) was the same as the one used for the internment from Sofia in May 1943, izseliha ni (we were interned). Education, family, mixed marriage,Footnote 9 and commitment to the new regime or its ideology were among the main reasons for non-emigration. In some cases, the interviewees had already been involved in the party structures, the army, or the police, which further complicated their situation. Furthermore, the participants in the 1941–1944 resistance had got important privileges:

-

– My parents and both my sisters and my brother left [se izseliha]. My brother married there and my sisters later too. They always asked us to join. And my father used to say: “They won’t come, they have jobs!” And we didn’t go. (Why?) Because (emphatically) we had other beliefs – to help Bulgaria! That was our creed. To stay here, to help! To organize! (Ms. ML, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– My father was a staunch communist. He wouldn’t allow a word to be uttered about moving anywhere. (Mr. DI, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– But I, with my totally washed brain, I said: “No, there is no socialism in Israel, there’s nothing I can do there.” … My father, he wouldn’t listen to a kid. But my opinion was rather welcome as he himself was hesitating. (Mr. EB, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– Only we the staunch communists remained here [believing] that we will be a pillar, that antisemitism will disappear. … We stayed with the conviction that after the war, the socialist ideas will solve all national issues, you know. (Mr. VB, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– I thought that this idea was something splendid – to work according to your capacities, to receive according to your needs, no capitalists, hindrances, and so on. I remember I said: “I don’t want to leave our socialist paradise for the capitalist hell!”… I still carry the weight of this ideology. (Mr. SM, first generation, Bulgaria)

These utterances seem to mirror the ones cited above about Zionism as the main reason to emigrate. In both Israel and Bulgaria, the propaganda machines would readily supply fuel for ideologically based interpretations. It is now difficult to assess the extent to which political belief was indeed the main motive to go or stay. As is seen from the quotes, there are shades of doubt, at least retrospectively: antisemitism did not disappear, the then-adolescent admits to have been brainwashed, and the last speaker still carries “the weight” of that ideology. Furthermore, the decision to stay in Bulgaria was in many cases motivated in more complex ways, by a variety of circumstances, as in the first quote, where the father points to having jobs as the main factor for non-migration and the interviewee does not challenge this hypothesis although she prioritizes ideological reasons. Another account of an interference of various reasons is the following, where the speaker points to a complex motivation including pragmatic reasons (studies, jobs), existential ones (families) but also emotional ones (attachment to the country, to the mountains), concluding with what looks like a tacit reproach to those who left:

-

– Almost all my kin left: my father’s brothers and his sister with my grandmother, my mother’s two sisters – only we stayed. Because my brother and I, we were studying at the university, because we were attached to our country, we married. My brother married a Bulgarian, I [married] a Jew. This does not matter. My son married a Bulgarian. This was not a factor. In addition, I am used to hiking in the mountains here, and they have no mountains there (laughs). Former partisans and political prisoners left, while my brother and I, we decided to stay. We had jobs, we had families, jobs. (Mr. AN, first generation, Bulgaria)

Family circumstances are a very common reason for staying back, sometimes the main one, especially in women’s stories. These stories mirror the accounts of the émigrés about whole families leaving together or about parents following their adolescent children in emigration.

-

– On my husband’s side everybody [left]: his father, his sister, his brother. On my side – my brother and I stayed with my mother… First, I couldn’t leave mother to my brother only [to take care of her]. And my brother was a communist – never, under no circumstances [would he leave]. My husband, may he rest in peace, never insisted… And, his family [was] there, mine here. (Ms. SD, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– My old parents who lived in Sliven and did not want to leave, they were already old, they had to rely on someone to take care of them. … I felt responsible for my old parents. (Ms. KS, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– Yes, there are many such Jews, devoted to Bulgaria. Of course. I, I dare say, I am a better Bulgarian than Bulgarians. Here, here is my motherland, here is my language, here were my children born, my husband… So, my husband advanced a lot at his job. Then the university was established and he was invited [as head of department]. And he said: “I’m very okay here.” (Ms. IA, first generation, Bulgaria)

Again, there is an assemblage of reasons in the last quote, with the speaker unable – or, not deeming it necessary – to prioritize any of them. However, there are other accounts, which tell about parting with family and friends. Their mood is different:

-

– Well, my kin, with their families, they left, one by one. We parted with grief because we didn’t know what they would still go through. (Ms. LB, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– I remember the great emigration to Israel, the anxieties around it. Worries after worries… Partings after partings… My mother and my father suffered a lot from them. (Ms. IF, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– My classmates, one of them left, another one left, and we’d go to the station and wave hands and cry. (Mr. LB, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– Oh, we’d go to the station, and they’d cry and sing. They were leaving and they were crying and singing at the same time. (Ms. SD, first generation, Bulgaria)

It was a common point in the narratives to enumerate relatives with their itineraries and how they made up their minds to stay or to leave. After a long account of her own family, an interviewee concluded: “Each family has its own saga and its own drama.” Some participants’ “drama” was that they had to give up emigration for fear that it could harm those family members who stayed behind.

-

– So, friends of mine started to get ready to leave. I was still at the university, in my second year. I told you that my education was mom’s main concern. In addition, her brother had participated in the resistance and our departure would have generally made his life worse…. First of all education and then, we would have aggravated the situation of that brother whom mom adored… especially after my father’s death he was like my second father. … Maybe I could have settled my personal life there, for I have not married… Maybe my life would have taken another course but… I am pleased with my life. (Ms. RL, first generation, Bulgaria)

In other moments of their interviews, non-migrants seemed to offer additional, less articulated reasons for not having left. They spoke of the settlers’ difficulties in the first years of their life in Israel, tacitly suggesting that these hardships must have been a disadvantage that had to be taken seriously when deciding to leave or to stay.

-

– At the beginning, they used to work even in road construction (Ms. LB, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– They all left, but the first years were very hard. First, they didn’t know the language. It was difficult to find a job. My brother used to even carry beams for the new construction. (Mr. SM, first generation, Bulgaria)

An even stronger argument was the story of Ms. KS’s sister that she told: the sister had studied dentistry for two years in Bulgaria, but this education “meant nothing” in Israel. Unable to continue her education, disappointed and depressed, she took care of her children and could only find a job as janitor in a kindergarten. Comparing her sister’s fate to her own career, Ms. KS concluded: “This is why I did not feel like going to Israel. I wanted to be a doctor, come what may.”

The Israeli interviewees also spoke about the initial hardships, but in another key: stressing that they had coped. The contrast between the privations during those first years, and the subsequent achievements is often essential for the emplotment of their narratives.

-

– It was very hard here. Everybody’s situation was difficult: no jobs, no food. (Mr. YN, first generation, Israel)

-

– As we came, the state was making its first steps. At times there was no food supply for more than a couple of weeks. (Mr. NN, first generation, Israel)

-

– But the situation was tragic. The people who came, they had to stand in line for bread and margarine – only that was available. (Mr. IM, first generation, Israel)

Unlike Israeli interviewees, none of whom admitted to have had any regrets about leaving Bulgaria, those who stayed behind sometimes expressed doubts about their choice – either spontaneously, or in response to interviewer’s questions:

-

– (Hasn’t it crossed your mind to move there, to live in Israel?) No, I told you, we were quite… (laughs) (And later?) And later it was already too late. When it becomes late, you have nothing to do there. Those who left in the great emigrations [izselvania] of 1948–1949, they were still young, in their strength… (Are you sorry that you did not leave?) Well, sometimes I am. Sometimes I am. (Mr. VB, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– Now, when my kin come from Israel, everybody asks me: “But why didn’t you leave?” – And I now say: “I wasn’t smart enough.” Indeed, I am sorry for not having left. (Ms. HL, first generation, Bulgaria)

There seem to have been various pressures within the Jewish community, but people decided whether to leave or to stay on their own. The choice was obviously a hard one, depending on a number of factors: social, economic, ideological, political, existential, emotional, pragmatic. Historical context, political conjuncture, communal attitudes, all played a role in it. As a result, the Jewish community in Bulgaria was severely curtailed, and its social fabric was torn. Jewish identity became less and less salient for a whole generation and was referred to in the 1990s as the “lost generation” (Koleva Reference Koleva2009). This topic remained underdeveloped in the participants’ narratives. One of them admitted that “identity was blurred” until 1989, and another deliberated that traditions were lost and now had to be “taught.” An interviewee from the younger generation offered a plausible explanation. Noting that his parents spoke Ladino only among themselves and did not teach it to the children, he went on to assess the changing salience of ethnic identity:

-

– And that was part of their, how shall I say, their strategy, strategy for social success, for integration into the environment. And now, if you talk to the older generation, they will tell you other things. That in the 1950s and 1960s they did want to integrate, this has been repressed. Now, they don’t feel comfortable to remember it. (Mr. EA, second generation, Bulgaria)

Indeed, the 1990s saw a revival of Jewish identity in Bulgaria, both in terms of interest in the Ladino language and culture, and more pragmatically, as a step toward emigration to Israel. Many participants spoke of the Second Aliyah, or the New Aliyah, in the 1990s, triggered mainly by economic reasons and facilitated by the end of the Cold War. For my interlocutors in Israel, it was essential to distinguish between “new” (economic) and “old” (patriotic) immigrants, the latter including themselves. They insisted on the difference in motivation of the migrants and the different situation in Israel, emphasizing their own endurance and their role in laying the foundations of their country, while the “new” migrants enjoyed substantial assistance to facilitate their integration.

Family Ties Across the Iron Curtain

Transnational family ties were planned to be a key focus of the interviews. It turned out however, that most participants had no stories to tell. In response to interviewers’ questions, few interlocutors remembered something specific. All confirmed that they kept contacts through letters, usually unable to answer about their frequency and content. Only one interviewee in Bulgaria showed the letters that her family had received. It was her mother who kept the correspondence, and after her death she took over. Others complained of the slow and irregular post: “We would wait over a month for the letter to come” (Ms. LB, first generation, Bulgaria); “For a long time we had no letters, there was nothing, it was like, chaos” (Mr. AP, first generation, Bulgaria).

During the group interview at the pensioners’ club, my questions about ties with kin in Bulgaria sparked a discussion among the participants as to how likely it was that the correspondence was monitored by the police, and which one – Bulgarian or Israeli. A published collection of State Security documents reveals that correspondence was indeed monitored: a report from November 1951 states that Bulgarian Jews “keep intensive correspondence with their compatriots in Israel, to whom they describe ‘the hard economic situation’ of the country” (Grozev and Marinova-Hristidi Reference Grozev and Marinova-Hristidi2012, 277). According to another report dated March 1959,

the correspondence… has a kinship character. The content of the letters is quite philistine. In about 20% of the letters the senders write about mutual visits and exchange of parcels. Political questions are not treated at all in the correspondence related to the Israeli line of work. The senders know that the correspondence is censored. The Israeli police cuts one side of the envelope and after the check they put a sticker. (Grozev and Marinova-Hristidi Reference Grozev and Marinova-Hristidi2012, 363)

None of my interlocutors remembered any stickers or other signs of surveillance of the correspondence.

Bulgarian participants, including those from the second generation, spoke of parcels from Israel, most often containing oranges. For them, this was a rare and exotic fruit, and a treat they appreciated even now:

-

– We used to get boxes of oranges. Very often. Well, very often – once or twice a year we could get a box of oranges. That was allowed, I don’t know why. And we used to eat oranges at home, a gift from uncle Yosef. (Mr. IF, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– For years on end, he [her uncle] used to send to the whole family – two uncles of mine, my mother and a cousin – he’d send everyone a box of oranges. Wrapped in papers with the word “Jaffa” on them. They used to come regularly, these boxes. Sometime in the winter, every winter. This is an absolutely stable memory. (Ms. EY, second generation, Bulgaria)

-

– I received parcels with oil, sugar, and oranges. And medicines. The medicines that a colleague of mine used to send – they were samples for free distribution and she, being a doctor, used to collect them and send them to me. And I would distribute them here. (Ms. SD, first generation, Bulgaria)

Sometimes, the parcels from Israel were interpreted by the recipients as a way of the emigrants to prove that they had made the right choice and they had overcome the initial hardships:

-

– They demonstrated in every way that they had succeeded. Even before, they used to send boxes of oranges, they used to send clothes, just for us to see that they were okay, financially okay. That’s how I felt about it… We had nothing to send them. We couldn’t quite afford. And so, we got used to wait for them to help us. (Ms. IF, first generation, Bulgaria)

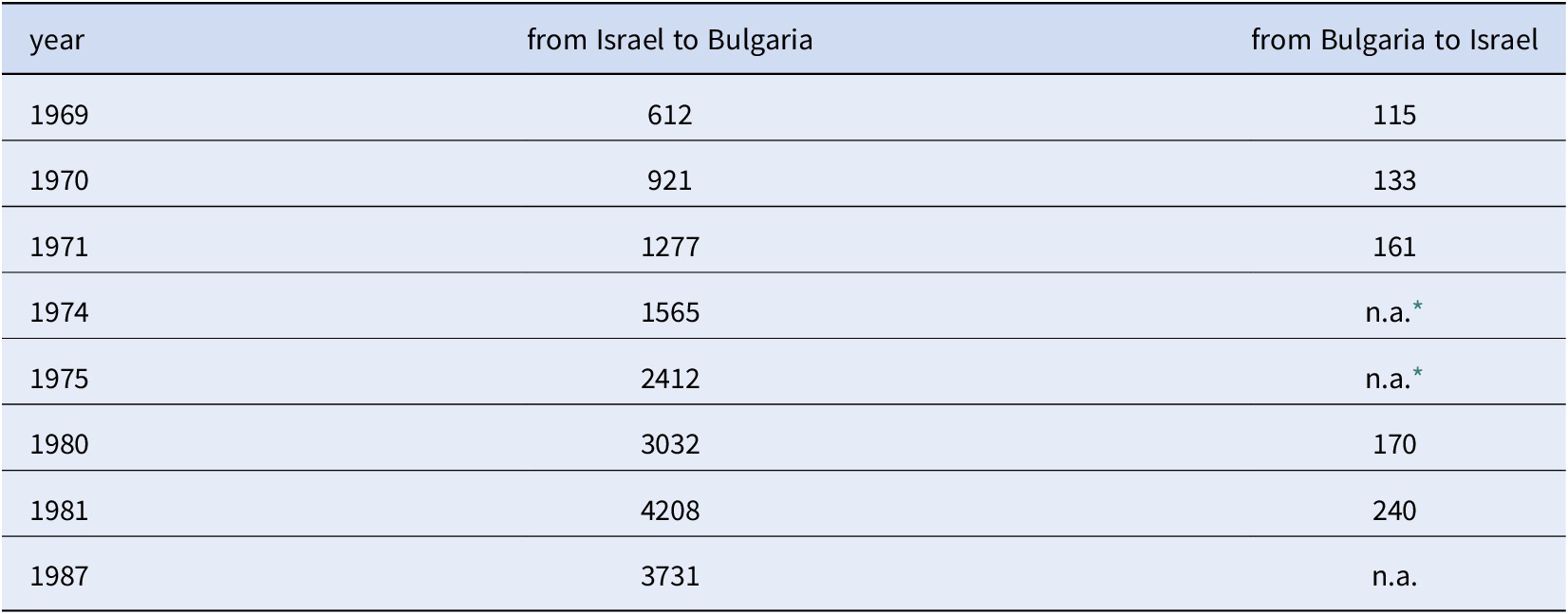

Another form of keeping family ties were mutual visits. These were not reciprocal: travel from Israel to Bulgaria was much more intensive than the other way round (Table 1). The Israeli participants stated that it had been “easy enough” to travel to Bulgaria. After 1967, when diplomatic relations were severed, visitors had to obtain Bulgarian tourist visas via another embassy: the Greek, the Italian, or the Austrian. From today’s perspective, none saw this as having been problematic. The most common topics in these narratives were the itineraries, places visited, and reunions with relatives and friends. Very often, the interviewees were accompanied by their children whom they wanted to show their birthplaces and to introduce them to Bulgarian kin and friends. They liked to calculate how many times they visited Bulgaria and for how long, stressing that Bulgaria was as dear to them as Israel. As one of them put it, to ask which country he loved better was as if to ask which parent he loved more, his mother or his father. These stories were readily told, eloquent and obviously also rehearsed on numerous occasions. However, it was not always clear if they referred to the period before 1990 or afterward, when many Bulgarian-born Israeli citizens indeed started to practice a “polygamy of place” (Beck): travel between Bulgaria and Israel became simple and frequent. No less importantly, many Jewish properties in Bulgaria were restituted to their owners who had to manage them.

Table 1. Numbers of visitors according to State Security archives. The author’s own elaboration based on Grozev and Marinova-Hristidi Reference Grozev and Marinova-Hristidi2012: 423, 425, 454, 456, 486, 492

* The total number from 1973 to July 1976 is reported to be 447 (ibid. 456).

Bulgarian interviewees seemed to be more aware of police surveillance. One of them told about a visit by the police, who came to inquire about her aunt. She had come to visit but stayed with her brother, rather than at her home as was initially planned. This inquiry showed that the police did take interest in the whereabouts of Israeli visitors. The shortage of personal stories about transnational family visits is partly compensated by the State Security archives. Travel to and from Israel constituted yet another concern of the secret services: visitors from Israel and Bulgarian citizens visiting Israel were closely monitored. The former often came with organized tourist groups, which, according to the reports, would “dissolve and turn from tourists into guests” diverting from their set itineraries and seeking to restore their one-time contacts (Grozev and Marinova-Hristidi Reference Grozev and Marinova-Hristidi2012, 486–487). They were reported to have

engaged mainly in Zionist propaganda and manipulation of our citizens of Jewish origin to flee from the PRBFootnote 10… they visit with their kin and acquaintances throughout the country and in conversations with them they propagate the high living standard in Israel, and one way or the other try to convince them to emigrate to Israel. (Ibid. 423)

The visitors to Israel, on the other hand, “in their majority… report to our organs about the interest of the Israeli investigating services in our country… However, there are some, who upon their return show reticence and reservedness” (Ibid. 427). Bulgarian participants also told about their visits to Israel. Some of them did the journey a few times throughout the years, especially on family occasions, either good or bad. The regulations for travel abroad from communist Bulgaria were rather strict. Applications for travel permits (exit visas) had to be submitted to the police and were often rejected, or issued at the very last moment. Some interviewees reported that their families could not travel together – some members had to stay “hostages” in Bulgaria. A participant visited his Israeli kin as newlywed and could not bring along his bride: “I had just married but I did not bring my wife. What an idiot! But I couldn’t tell them why it was so” (Mr. IF, first generation, Bulgaria). As a rule however, Bulgarian Jews did get travel permits to visit kin in Israel. As one of them reasoned, “Generally speaking, our communist socialist motherland was very mindful about its international image.”

In most cases, the interviewees talked about family and kin reunions. Those whose relatives used to live in kibbutz described the organization of the work and life there. Having been used to the life in Sofia or another city, they were ambivalent about the organization of the kibbutz:

-

– Everybody in the kibbutz had their meals together, in a common canteen and she [her aunt] got permission for us to have meals there as her guests… I felt very restrained in that kibbutz because they could go out only if the management provided for them transport or something… I didn’t like that everyone dressed almost the same and… I didn’t like this restricted way of life. (Ms. RL, first generation, Bulgaria)

The Interviewees who visited Israel as children or adolescents, and stayed in a city, had very different memories:

-

– Toys! – that was an incredible multifariousness, colorfulness, as if you were in a different world. Such plenty made a formidable impression on the children – the huge chocolates filled with what not… A great contrast [to Bulgaria]. (Ms. LZ, second generation, Bulgaria)

-

– I went there with a degree of prejudice, shall I say, that I wasn’t going to choose, that my country was Bulgaria, not Israel. Obviously, I was already indoctrinated enough. Of course, it was very exotic, very interesting… I drank Coca-Cola, they bought me colored pens, which was great, they gave me a new ball… Yes, I was impressed but somehow – as a tourist. (Mr. EA, second generation, Bulgaria)

The latter interviewee, however, brought in another perspective: he reckoned that those travels, the intercultural contacts, and the exposure to other languages at a young age opened his intellectual horizon and helped in his professional career later on.

The other aspect of the travels – the surveillance and the attempts to recruit travelers as state security informers – popped up rarely in the recollections. One interviewee admitted to have been asked by the secret police to report on his visit upon return. Another account, which conveys this atmosphere, is the one by a participant who did not dare to express a positive opinion of anything he saw during his visit to Israel in 1965 for fear that it might be reported to the police in Bulgaria:

-

– They took me to a variety of places. And they asked: “Do you like it?” Theatre, exhibition, life – if I liked. How did I find the shops. I never said: “Yes, wonderful. Yes, great.” I already lived among friends who talked to me and persuaded me how rotten the regime was. On the one hand, I opposed them; on the other hand, I saw that they were right. I was full of doubt and that kind of stuff. But also with a lot of fear of the agents, of the State Security, of the secret services. Mostly fear of the services, no matter Russian or Bulgarian. And I, as it were, suffered from spy mania, I was afraid of being charged with espionage, of being charged with hostility. And of being deprived of the right to travel abroad because of that. This is why, I was in Israel, but I never praised Israel. (Mr. IF, first generation, Bulgaria)

While this account displays a certain self-irony, the fear was not unfounded. Another participant was indeed sentenced in 1960 to ten years in prison (of which he served five) for espionage. The reason was that he visited the embassy of Israel a few times to collect medicines for his wife who suffered from tuberculosis. The diplomatic courier service was the only way for his brother to send the precious medicine from Israel.

Other participants dwelled on what it meant to have kin in Israel for the citizens of Bulgaria, especially after 1967. They reported that contacts were subdued, in some cases even discontinued, as was the case with Mr. NN’s sister-in-law: her brother stayed in Bulgaria, and he asked her not to send letters so as “not to create difficulties for him.” A couple of the Bulgarian participants told of difficulties with acquiring a job, even when they were the preferred candidates. In communist Bulgaria, detailed information about relatives abroad was to be included in the forms one had to fill in when starting a new job.

-

– The “Relatives Abroad” entry was meant mainly for us [Jews]. Because very few of the others had [such relatives]. This was the reason why my conationals in Bulgaria were not appointed at more responsible positions. (Ms. EJ, second generation, Israel)

The same interviewee believed that she got a job at the Bulgarian news agency only because she had changed her family name after marriage and her Jewish origin was thus obscured. In spite of such fears and of the disadvantages of having relatives abroad, Jews in Bulgaria did keep their transnational kinship ties as one of the very few permeable spots of the Iron Curtain.Footnote 11 What managed to perfuse through it were not just the boxes with oranges that many of the Bulgarian interviewees remembered, not only the reunions of cousins who often did not know each other, but – perhaps most importantly – a support for their cultural identity in the face of the assimilation into a monolithic “socialist nation.”

“First Generation,” “Lost Generation”: Ideologies and Mythologies

A common theme in the biographical narratives of many interviewees, which emerged spontaneously, was the idea of having been pioneers, builders of a new world. The Israeli participants insisted on differentiating between their own Aliyah and the one of the 1990s, stressing that they had been there at the founding moment of their country and had “turned the desert into gardens.” Thus their own agency was seen as part of Israel’s becoming a nation:

-

– We came with the great desire to build this country. We didn’t, how shall I say, we didn’t want any help. Especially the Jews from Bulgaria – we never asked for help. (Mr. MP, first generation, Israel)

-

– So, we set off with nothing and we came here in Israel. I thought it was a desert here, which was true – not Tel Aviv of course, but all the rest. (Ms. MJ, first generation, Israel)

-

– Not knowing where we headed. To a desert. That was Israel before. (Mr. LL, first generation, Israel)

-

– And he [uncle] established a kibbutz in the desert: they advanced with a caravan of camels, they reached a place and they said, we’ll settle here. (Mr. EA, second generation, Bulgaria)

The notion of a desert, which the settlers turned into a garden, is a common one in the Israeli interviews, obviously drawing on public narratives. What probably used to be a propaganda cliché has found a place in family mythologies. The metaphor of the desert conveniently omits the Palestinian population, presenting the settlers as colonizers appropriating the wilderness – a trope characteristic of settler colonialism with its drive for ecological transformation (Veracini Reference Veracini, Ness and Cope2019).Footnote 12 But there is also something else: the talk of a pioneer generation that built their new country highlights solidarity and common effort, while it probably screens out divisions, inequalities, and possible tensions among different immigrant communities, which sometimes popped up in comparisons of the “Bulgarians” (as they identified themselves) with immigrants from other countries. Moreover, the pioneer narrative glosses over possible tensions even within the Bulgarian-Israeli community. Ms. MJ insisted that I record the names of those “Bulgarians” who made it to the intellectual and cultural elite of Tel Aviv: a few professors of medicine, the architect of the first high-rise constructions, the host of a popular radio program… She was frustrated about what she considered to be a misrepresentation of the “Bulgarians” in Israel as boorish and low-status: “they always show Bulgarians dancing horo, the old women of Yaffo.”

The idea of having been a pioneer generation building a new society on the ruins left after WWII surfaced in the narratives of some Bulgarian participants as well, albeit less often and in less articulated form:

-

– We were among those who stayed here to build socialism. Now people don’t know how much we used to work. We’d work all day at our workplaces and then we’d go to organize and create new people. … We built Bulgaria. With voluntary brigades. We worked a lot and with no pay. (Ms. ML, first generation, Bulgaria)

-

– I was an organized young man, I was a member of an organization that had instilled high principles into my head and I knew that I ought to work in a real factory… And we used to have meetings, we used to have initiatives, we used to have various things. (Mr. IF, first generation, Bulgaria)

Interestingly, the first quote belongs to a woman who worked as a seamstress all her life – before and during the communist regime. She did not experience any social mobility and did not benefit in any way except, obviously, acquiring a resource to construct a vindicated identity for herself. The second quote, as well as most of the other similar statements, is more ambivalent. The reason for this may be that the public memory in postcommunist Bulgaria no longer offers stable props for such narratives. The changing discourses about what was socialism and how to relate to this past have set the stage differently for personal recollections as well.

Much more salient for the participants in Bulgaria was the attitude toward their Sephardi roots and identity. This was a frequent topic, especially in women’s narratives. The older women saw themselves as custodians of Sephardi traditions, which they had helped to revive in the 1990s. It was these traditions, rather than Judaism, that served as anchors of their self-identity. They liked to talk about the language, the cuisine, the celebrations in their parents’ families. They knew a lot about their ancestors and about the origin and the migrations of the Sephardi Jews in general. The ubiquity of these themes is an obvious result of the revival of Jewish identity in Bulgaria since the 1990s. In contrast, the Israeli interviewees (with one exception) did not even mention their Sephardi origin, preferring to identify themselves as Bulgarians.Footnote 13 None of them spoke Ladino, but their Bulgarian was very good and most of them had passed it on to their children. On the one hand, this might be understandable in a society of immigrants where the first generation used to identify with their countries of origin, not only among themselves but also for statistical purposes. This situation has been convincingly conceptualized in the perspective of settler colonialism (Veracini Reference Veracini2018). On the other hand, the efforts to build a new nation by absorption of mass immigration in the context of Ashkenazi cultural hegemony did not encourage sticking to Sephardi identity (cf. Benbassa and Rodrigue Reference Benbassa and Rodrigue2000, xxi); generally, concepts articulating cultural specificities were avoided (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2008, 177). The ethnonym “Bulgarian” pointed to their European origin, similar to the founding elite of the state, and set them apart from other Sephardi groups (Middle Eastern) stigmatized as backward and culturally inferior.Footnote 14

However, what is common in the two countries is the pattern of hybridization of cultures: each Jewish community interacted with the hegemonic culture in the respective country and produced hybrids without challenging the overarching national narrative but rather in its interstices. This was the case with fitting into the “socialist nation” in Bulgaria but also in Israel, facing the challenge of building a nation out of a multitude of diverse communities.

Conclusion: Negotiating Transnational Belonging

The oral history in Bulgaria and Israel offers a unique chance for comparison of the life courses and self-identities of individuals belonging to the same nationality and the same generation, who spent most of their lives on the opposite sides of the Iron Curtain. Those who stayed in Bulgaria had to insert themselves into a monolithic nation, subduing their cultural identity, but were nevertheless regarded with suspicion by the regime. Those who emigrated to Israel had to participate in the building of a new nation and its identity, which had its costs as well.

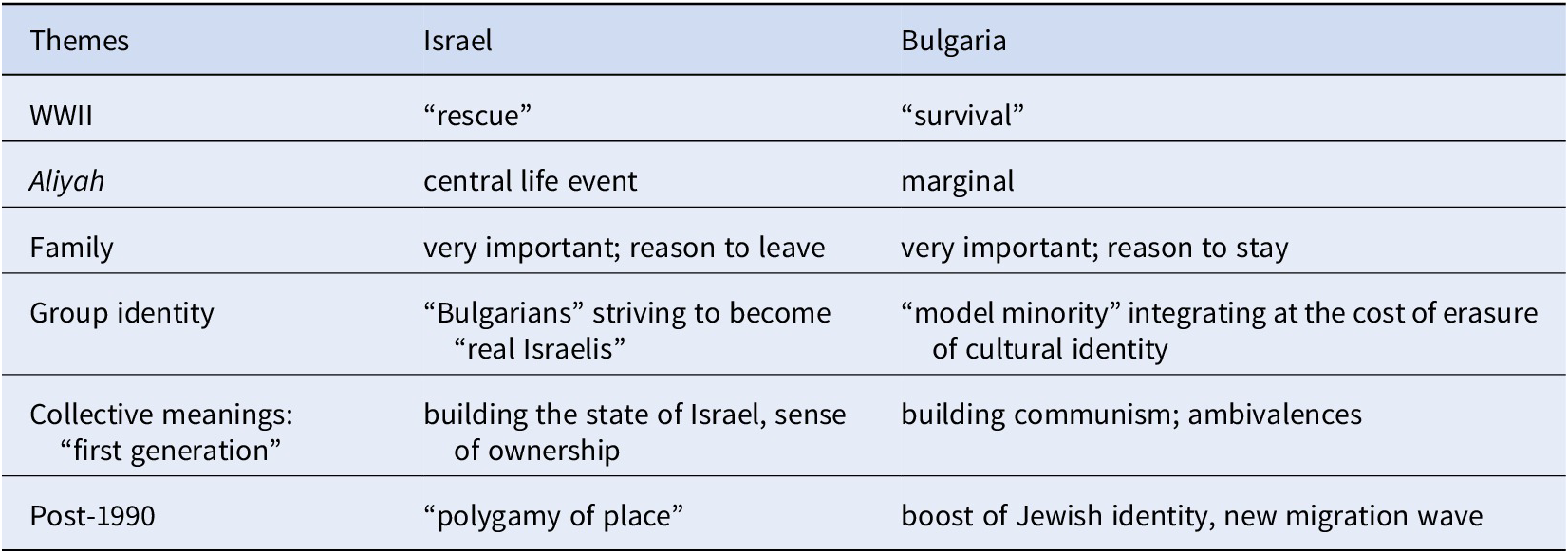

A few common themes run through the biographical narratives, which are handled somewhat differently by the two country-based groups of participants (Table 2). The anti-Jewish repressions during the war were a common topic in the life stories, but the personal memories differed a lot depending on the age of the reminiscers. The oldest participant protested that those who “wore shorts” had no right to testify, for they had seen everything through child’s eyes and had not experienced the real suffering. Another division followed the national borders. Participants from Israel tended to speak less of the suffering and more of the help they received from their Bulgarian neighbours. While interviewees from Bulgaria more often referred to their experience as “survial,” those from Israel tended to consider it a “rescue.” Some of these assessments drew more on public narratives (for example, Bar-Zohar Reference Bar-Zohar1998 in Israel) than on one’s own experience. Thus, the interviewees indirectly took sides in a public debate with high political stakes, which has been simmering in Bulgaria for a couple of decades with occasional bursts in the media.Footnote 15

Table 2. Summary of common themes and their typical handling by the interviewees in the two countries

The comparison suggests that different national settings and ideologies have molded personal recollections, framing the retrospective glance toward one’s life and times. The official memory cultures in the two countries have set the stage differently even for the recollections of the same events and processes. The Israeli “Bulgarians” shaped their memories of WWII under the influence of the public memory of the Holocaust in their country,Footnote 16 and fashioned their life stories to converge with the story of their nation. Thus, they represent a “canonical generation” (Ben-Ze’ev and Lomsky-Feder Reference Ben-Ze’ev and Lomsky-Feder2009), which identifies itself with the nation’s foundational past. If nationhood is to be viewed as the product of storytelling, then their stories largely coincide with the normative narrative and inscribe themselves into the “discursive technology with which a nation-state is formed” (Çinar and Taş Reference Çinar and Taş2017, 662). Their voices have a certain symbolic authority and are rather uniform, merging into one collective voice. Conversely, the ideological canon to which the Bulgarian “first generation” used to adhere was dismantled after the end of the communist regime. This has allowed for greater multivocality and critical attitudes while stripping the stories of possible normativity.

These findings invite a step further from generations in the family, as discussed by the interviewees, to historical generations and to the notion of a transnational generation as a community of experience and a community of memory – that is, a generation identified on the basis of shared experience, in which shared narratives are anchored. The grounds for such an understanding are provided by Karl Mannheim’s (1952) now-classical theory, built upon the thesis about the link between biographical and historical time. For Mannheim, the social location of a generation in the historical process (Generationslagerung) sets up the objectively feasible parameters of experience, while the generation as actuality (Generationszusammenhang) occurs when a generation is exposed to important historical events and has an active part in them, achieving a relatively high level of collective mobilization. This was exactly the case with the Jewish youth in post-WWII Bulgaria. Because different groups from the same generation react differently to the same events, Mannheim separates out generational units (Generationseinheiten) in order to demonstrate the boundaries of solidarity based on shared experience. This notion enables the linkage between objective conditions and their subjective interpretations, between personal experience and social context, biography and history. What turns generations into mnemonic communities is that their members are equipped not just with shared experience, nor merely with a shared understanding of it, but also with an awareness of the commonality of this understanding within the generational bounds (Koleva Reference Koleva2022, 255–264). A generation is only present if it has got a retrospectively devised system of reference points, which differentiates this particular generation from the previous and the subsequent one (Borneman Reference Borneman1992, 46; Giesen Reference Giesen2004, 33–37). As was shown above, the interviewees used this notion to distinguish themselves from their parents and from their successors. When they talked about their peers leading the Aliyah or resolving their parents’ hesitations, or opposing their parents by not following them in emigration, they evoked the notion of an “active generation” (Edmunds and Turner Reference Edmunds and Turner2002, 16–18), one that directs not only family itineraries but also political futures. Also, they re-tooled the desert-metaphor when describing the pensioners’ club as an “oasis of Bulgarian speech and Bulgarian memories,” admitting that the next generation no longer had that sentiment for Bulgaria.

In addition, the comparison also brings forward a notion of generation in the context of a transnational simultaneity. In spite of the differences in the reminiscences of those who emigrated and those who stayed, interviewees in both countries tended to assign the same symbolic significance to key past experiences: whether they left or stayed, they did it for their country, or for their family, or both. The post-war experience served as a marker helping them to authenticate themselves to each other and to other generations. The point in time – biographical and social – at which they produced their life narratives, made it possible to oscillate between the registers of the nation and of the family, to intertwine, reconcile, and project the one onto the other, practicing a cultural intimacy of sorts. Thus, the comparison also reveals the complexity and the dynamics of the “transnational”: from the prevalence of its political and economic aspects to a cultural transnationalism, a dynamic web of spaces, places and itineraries, both geographical and symbolic. While rooted in the respective national contexts and mythologies, the memory narratives of the participants spill over them into what might be seen as a “conciliatory culture” (Stańczyk Reference Stańczyk2016) – discursive strategies highlighting similarity rather than difference, but also a willingness to practice “polygamy” not only of place but also of belonging, an attempt to maintain in-betweenness, to assert and manage transnational belonging, to reimagine one’s affiliation to one’s imagined community through the amity and closeness of the family, to bridge spatial, temporal, and emotional rifts. Even if they used to be implicated in the national(ist) projects of their homeland, the Bulgarian Jews and the Israeli “Bulgarians” have subsequently formed a transnational community that challenges national borders and the idea of national container-cultures in favor of mixed cultural formats, hybrid identities, and more fluid and dynamic relations.

Financial support

Institute for the Study of the Recent Past, Sofia.

Disclosure

None.

Appendix: List of Interviewees