Introduction

Above all, what is striking about the secret societies of the complex hunting and gathering cultures of the American Northwest Coast (Fig. 2.1) is the remarkable amount of time, effort, and expense that went into the rituals and performances. Although no reports deal with the amount of time required for the preparations, they must have taken many months, not counting the years of wealth accumulation required for initiation into the more important positions, the weeks or months of seclusion of the candidates, and the years of prohibitions after initiation. There were unusual materials to be procured; masks and elaborate costumes to be made; special dramatic or stage effects to be crafted or arranged (with confederates helping to make noise or other effects on house roofs, outside the houses, or even outside villages); feasts of the best foods to be procured, prepared, and organized; permissions from secret society “marshals” had to be obtained; gifts to be arranged; many songs and dances to be learned; and numerous meetings and rehearsals. The performances themselves usually lasted a number of days and often went on all night or could be repeated in each house of a village. According to McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948b:1), one host’s performance succeeded another so that there were dances on a nightly basis over the three months of the winter ceremonial season.

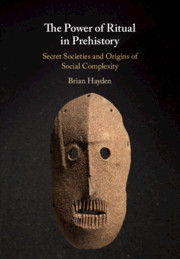

2.1 Map of ethnic groups in the Pacific Northwest Coast referred to in Chapter 2.

However, there were also considerable risks. McIlwraith, Drucker, and Boas all noted that deaths during long seclusion periods were not uncommon (see “Ecstatic States”), besides which blunders during performances could entail punishments including death. Sponsors or hosts of the performances had to pay for everything, but they also had to obtain permission from secret society marshals or leaders, at least in some groups like the Bella Coola. It is often difficult to know to what extent the rapid breakdown of secret societies had altered their organizational structures by the time ethnographic observations were made. However, given all the costs, risks, and privations, one would expect there to be substantial benefits, at least traditionally, to membership in the secret societies and for sponsors of the elaborate performances. Yet, what these benefits were has not been meaningfully addressed by most ethnographers. We might anticipate that the prospect of acquiring substantial power and some means of accessing wealth was associated with memberships; however, details are elusive.

Boas (Reference Boas1897:661) stated that all the secret societies of the Northwest Coast were very similar, often even using the same names. They all used cedar bark as badges, including head rings, neck rings, and masks. Loeb (1929) saw the possession and mask characteristics as relatively “recent” influences from Siberian shamanism; however, this was speculative. The Tlingit appeared to represent the northern limit of secret society organizations (Boas Reference Boas1897:275). They were present at Wrangell (Southern Tlingit), with some traces at Sitka, but not farther north (de Laguna Reference De Laguna1972:628; Olson Reference Olson1967:118), except possibly for Point Barrow Eskimos (see Chapter 6).

Similarities with California

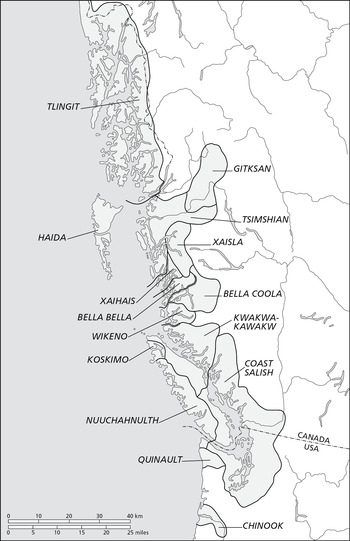

In general, there were many, sometimes striking, similarities between the central California Kuksu secret societies and the secret societies of the Northwest Coast. These included the themes of death and resurrection of new initiates; the disappearance of new initiates from the ritual gathering (sometimes ejected or thrown out) and a period of seclusion during which the initiate was supposed to have ascended to the upper realm of spirits from which he returned in a wild state and needed to be calmed (including by ritual dousing with water); portrayal of ghosts as either possessing people or as visiting the living (e.g., McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:6,211); the use of dances and disguises by performers to assume the role of, or to channel, specific spirits (Fig. 2.2); recognition or certification of successful initiation by publicly performing the dance received from spirits (e.g., McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:23); induced bleeding at the mouth as a sign of supernatural power or the possession by powerful spirits; the need of new initiates to cover their heads when temporarily leaving the ritual location (so as not to lose their spirit power – per McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:166); the high costs of initiations; the use of decorated staffs or sticks; the use of whistles and bullroarers as secret voices of spirits; the use of bone drinking tubes by new initiates; the use of stage magic to demonstrate supernatural powers to the uninitiated; and perhaps even a common derivation of the names for the cults or members, e.g., Kuksu in California and KuKusiut in Bella Coola.

2.2 Kwakwakawakw Wolf Society dancers in one of the residential long houses on the Northwast Coast, as depicted by Franz Boas (Reference Boas1897). Note the large central fire.

There were several differences as well. Notably, the Northwest Coast secret societies involved distinctive possessions by the guardian spirits of each secret society and masks were used to personify those guardian spirits whereas these features do not occur in other areas (Loeb Reference Loeb1929:266,272–3). Possession only occurred in secret societies of the Northwest Coast, and is seen as a Siberian influence by Loeb (Reference Loeb1929:266). Moreover, while groups in the Canadian Plateau and California used sweat houses, most groups in the Northwest Coast did not use them.

Because of the implications concerning the dynamics of secret societies and their interactions, several minor but striking features of some Northwest Coast secret societies held in common with those among the Ojibway are also of interest. These include the “shooting” of power into new initiates or others by means of special objects such as quartz crystals used by the Bella Coola and Nuuchahnulth (also known as the Nootka) or by cowrie shells used by the Ojibway. In both areas, the person “shot” fell down as if dead and was then revived. Some detailed similarities also exist between Northwest Coast groups and Plains groups such as the piercing of the skin on the back or arms or legs and the suspension of the individual(s) by ropes attached to items thrust through the skin (e.g., Boas Reference Boas1897:482).

These detailed ritual similarities between groups separated by great distances may indicate that members of secret societies participated not only in regional interactions but more far-flung connections, creating an interacting network of people who freely exchanged, bought, or borrowed elements of particular interest, introduced new practices to their own local groups, and promoted their adoption, much as described for Plains secret societies (Chapter 5). Individuals from other villages or regions in the Northwest were particularly welcome at secret society rituals, and special attempts were made to impress them, for example by conferring on them the exclusive honor of publicly receiving “potlatch” gifts (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:28).

Origins

Boas (Reference Boas1897:664) maintained that the origins of secret societies were closely connected with warfare. Ernst (Reference Ernst1952:82) similarly thought that the Nuuchahnulth Wolf Society was originally warrior-based, noting that there was a strong warrior emphasis on Vancouver Island. Indeed, pronounced warrior aspects existed in many secret societies, including warrior dances and the destructive use of clubs in warrior spirit possession dances (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:202,205–6,214; Olson Reference Olson1954:248). On the other hand, McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948b:266) thought that the Kusiut Society was originally a band of elders.

Tollefson (Reference Tollefson1976:154) argued that secret societies were not important among the Tlingit because they had such strong shamanic traditions and people went to shamans if they wanted supernatural power, negating the need to become involved collectively in a secret society to obtain such power.

Overview

Core Features

Motives and Dynamics

Ethnographers on the Northwest Coast rarely discuss motives behind forming or belonging to secret societies. However, when they do raise such issues they strongly emphasize the practical benefits, particularly obtaining power over other people and dominating society via the use of terror, violence, and black magic tactics (e.g., Drucker Reference Drucker1941:226). Secret societies have even been referred to as “terrorist organizations.” Since power appears to have been the goal of membership, and a frequently attained one, competition for positions was frequently intense, resulting in a very fluid and dynamic ritual structure with new dances and entire ritual organizations being constantly introduced with only the most successful persisting or flourishing. This is a recurring characteristic of secret societies in most regions of the globe.

Wealth Acquisition

There is little information on how members, especially high-ranking members, benefited materially from their positions other than from initiation or advancement payments. There are a number of allusions to candidate families hosting feasts as payments to the members of secret societies. Those who transgressed society rules could be killed or forced to provide feasts to secret society members. There were unspecified “compensations” paid to society members for training, passing power, and returning spirit-possessed individuals back to normal states. Some members also claimed to steal the souls of spectators which could be returned to the rightful owner upon payment. “Shamans” similarly were said to make people sick so that they could extract high prices for the cures.

Relation to Politics

There was a strong relationship between chiefly offices and the most important, highest ranked secret societies, or, in some cases, the highest positions in secret societies. Some societies such as the Sisauk Society only admitted “chiefs” (the heads of corporate kin groups) and their power was said to derive from their membership in the Sisauk Society.

Tactics

Ideology

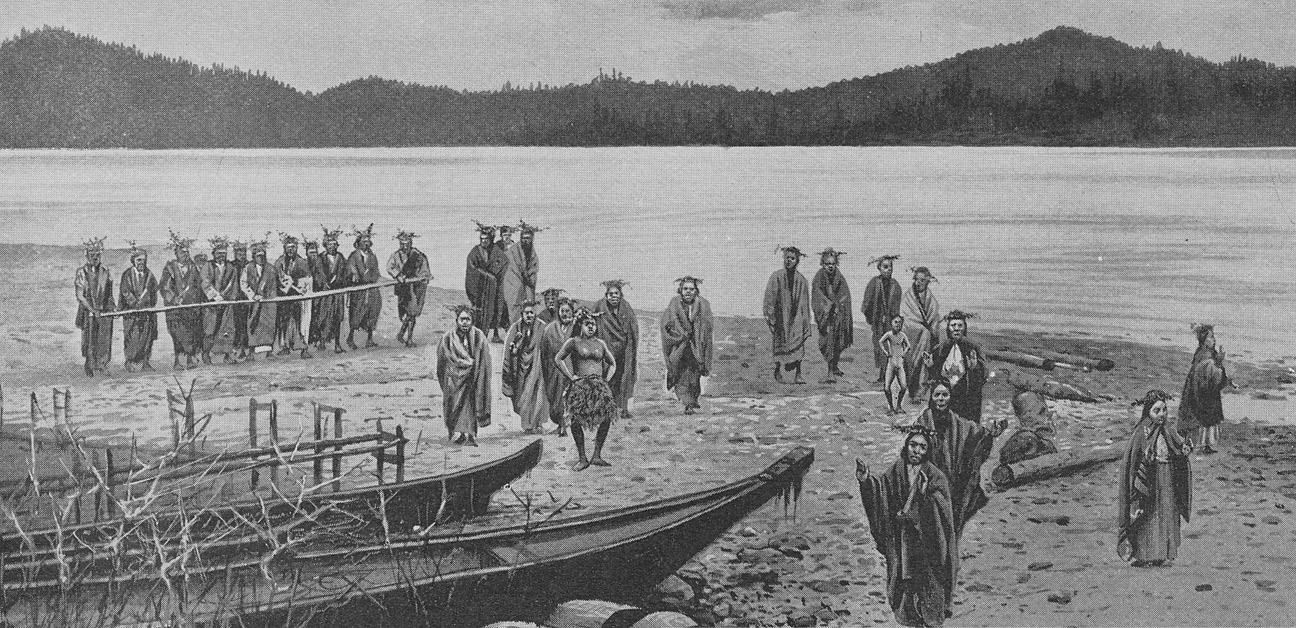

In order to justify the use of terror and violence, secret societies promulgated a number of key ideological premises. These included the existence of members’ ancestors who acquired supernatural powers from spirits which could be passed on to descendants or acquired anew directly from spirits. These powers could be accessed in winter ceremonial times via dances, wearing masks, singing, rituals and special paraphernalia resulting in the possession of members by their ancestral spirits – which were subsequently exorcised by other members. Supernatural power was portrayed as dangerous and hence required special training to safely control. In order to emphasize their supernatural powers, secret society members often referred to themselves as shamans, whether they had shamanistic abilities or not. Those undergoing initiation were said to die and travel to the spirit realm where they became spirits and returned in a new form (Fig. 2.3). The societies claimed that they could bring the dead back to life, at least in some cases. The development of skills and success in all domains was supposed to be dependent on supernatural help which, in turn, was dependent on wealth. Conversely, wealth was a sign of supernatural favor. Because of such warrants, powerful chiefs could make their own rules and disregard conventional practices.

2.3 Depiction by Franz Boas (Reference Boas1897) of a new Hamatsa initiate (the central figure with bare torso and cedar bough skirt) on the Northwest Coast returning from his sojourn with ethereal powers and landing on earth on the beach. Note the women involved in the procession as well as the young naked boy with the same stance to the right of the initiate. He may also have been given some status within the secret society.

Community Benefits and Threats

While the more public secret society ceremonies certainly provided entertainment for their communities, it is difficult to find many references to other community benefits aside from occasional mentions of empowering warriors or healing, and even these last could be suspect as sickness was sometimes said to have been induced by secret society members in order to get high commissions for healings. The overwhelming emphasis in the ethnographies is on the dire consequences of ignoring or unleashing the supernatural powers dealt with by the secret societies, as palpably demonstrated by the violent acts of masked spirits and the cannibalistic manias of people who were possessed by spirits. Houses could be destroyed, dogs torn apart, people bitten by those possessed, and such spirits could take possession of initiates for any perceived slight at any time.

Esoteric Knowledge

It was the secret societies that claimed to hold the knowledge of how to control the terrible power of the spirits. Others who tried to do so were said to go insane, sicken, or often die.

Exclusiveness, Costs, and Hierarchies

While there were some secret societies of lesser importance which admitted a wide range of members, the more important secret societies were very exclusive and used the criteria of wealth, descent, and sociopolitical position to exclude non-members. In some cases such as the Nuuchahnulth Wolf Society, all males were expected to become non-members at the entry level of the society. (A number of variant names are given for the Nuuchahnulth Wolf Society, e.g., Klukwalle (Ernst Reference Ernst1952:2,19), Tlokoala (Boas Reference Boas1891:599); see Ernst (Reference Ernst1952:2) for a comprehensive list.) However, there were a number of ranked specialized positions within these societies which constituted a kind of separate society. These positions were much more exclusive. A number of Northwest Coast societies, especially the Hamatsa (Cannibal) groups, were exclusively for wealthy chiefs or elites. The initiation feasts in some groups constituted the greatest undertaking of a man’s career. Initiation costs could be enormous and sometimes entailed many thousands of blankets, as well as bracelets, decorated boxes, food, kitchen ware, canoes, pelts, shells, masks, and other wealth items, in one case enough to fill a square that was 100 feet on a side. The higher one progressed in the ranked positions of the secret societies, the more costly and exclusive the initiations became.

Public Displays

In order to persuade community members of the power of the supernatural forces that secret societies claimed to control, they periodically put on dances, displays, and processions of some of those powers for everyone to see. Society members impersonated spirits by the use of masks, costumes, and unusual noise-making devices. They also developed highly sophisticated stage magic techniques, all of which provided fascination and entertainment for non-initiated spectators, as well as instilling terror. Thus, spectators witnessed dancers becoming crazy and possessed, going around biting bits of flesh from people, or tearing dogs apart and eating them. Some of those who were possessed destroyed house walls and furniture. Some could handle fire, keep burning coals in their mouths, make rattles dance by themselves, change water to blood, bring dead salmon to life, have arrows thrust through their bodies. Some initiates even cut off their own heads only to be brought back to life. The material power (derived from spirit power) of the society was also manifested in the form of lavish feasts, spirit costumes and masks, and the destruction of property such as the burning of fish oil and killing of slaves.

Ecstatic States

There can be little doubt that at least some of the initiations and dances created altered ecstatic states of consciousness for individuals. The lengthy periods of fasting resulting in emaciated initiates, and the days of drumming, drone-style singing, dancing, and the psychological stresses of confronting or even eating corpses all must have had mind-altering effects. These trials were so severe that candidates sometimes died during their ordeals. The effects of entering such altered states would have created more convincing performances for spectators, but also would have persuaded some of those who experienced possession states of the reality of the spirit powers, thus binding them more strongly to secret society organizations and leaders.

Enforcement

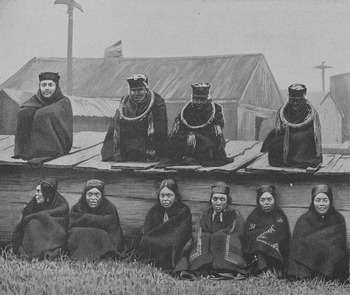

If uninitiated spectators failed to be awed or suitably fearful of the ideological claims and spirit performances, secret societies generally resorted to coercion and violence to achieve acquiescence from all community members. Those who did not accept secret society claims or dictates were targeted and frequently eliminated one way or another. Some groups employed spies to identify such individuals. Thus, as tends to be true of many secret societies, anyone disclosing or discovering that the appearances of the spirits were really humans in masks, or anyone disclosing the tricks behind stage magic performances, was either inducted into the society (if deemed desirable) or killed outright. This was the common procedure for dealing with individuals who entered – either on purpose or accidentally – designated sacred spaces of the society. Punishments were also meted out to society members who revealed secrets, or to those who let their masks fall in performances, or who made staged displays that failed to work. Killings for transgressions of conduct rules during dances became prevalent in some groups. Lesser offences such as coughing, talking, or laughing during dances could be punished by clubbing, knife jabs, disfigurement, or fines (Fig. 2.4). Above all, it was the use of violence in these situations and in states of possession which warranted the use of the terms “terrorist” and “terror” to describe the organizations and their tactics.

2.4 Kwakiutl Hamatsa members who acted as enforcers (Noonlemala) of society rules (Boas Reference Boas1897). Note the cedar bark ring worn by the central figure as a sign of initiation, and probably the director of the group.

Sacrifices and Cannibalism

While the sacrifice of slaves during potlatches and secret society performances seems to be generally accepted as an aspect of some Northwest Coast ceremonialism, the issue of cannibalism is strongly debated. There are numerous claims of first-hand accounts, and there appear to have been desiccated corpses involved in ceremonies, but it cannot be known whether human flesh was actually consumed, or perhaps only touched to the mouth, or whether stage illusions were used to make it seem as though cannibalism was occurring in order to intimidate spectators or to establish fearsome reputations. In other parts of the world such as Melanesia and Africa, secret societies were more certainly using cannibalism as a means to intimidate any who opposed them (see Chapters 8 and 9). Thus, this may have been a tactic used by a range of secret societies both ethnographically and prehistorically, including on the Northwest Coast.

Material Aspects

Paraphernalia and Structures

A broad array of ritual paraphernalia was used by Northwest Coast secret societies. In general, these included masks, various forms of wood whistles, bullroarers, drums, rattles, rattling aprons, bird bone drinking tubes, horns, trumpets, smoking pipes, bark rings, certain bird skins or animal pelts, decorated staffs and poles, copper nails for scratching, quartz crystals, and some special stones.

The general ritual settlement pattern was to hold initiation and other important ceremonies inside a house in the community which was appropriated for the purpose, suitably rearranged, and cordoned off. Special meeting places were also established at varying distances, from 150 to 400 meters, outside the villages, although no structures are reported to have been built at such locations. Ritual paraphernalia was sometimes stored in “faraway” locations, including rock shelters and caves. Candidates for initiations were taken to secluded locations outside the villages where they camped for the duration of their seclusion, probably not too distant from villages. Caves are mentioned in some areas as being used for seclusion, meetings, or ritual storage locations of secret societies. There are thus both central (village) loci of secret society activities and a variety of remote (non-village) loci for society activities. The use of caves is of particular note given their archaeological importance and frequent evidence of ritual use.

Burials

Information on the burial of high-ranking secret society members is very limited, perhaps because such individuals were generally chiefs, and chiefly burials are usually described in terms of the sociopolitical roles that the deceased held, reflected in the sculptures on their burial poles. Thus, in the case of the Northwest Coast, it is difficult to distinguish any unique features of burials of secret society members. Kamenskii (Reference Kamenskii1985:78) does report that shamans were buried in caves, but whether he was referring to bona fide shamans or secret society members referred to as shamans is uncertain.

Cross-cutting Kinship or Regional Organizations, and Art Styles

Since many specific roles and dances in secret societies could only be occupied or performed by members of specific descent groups, this guaranteed that a variety of descent groups would be represented in the membership of specific secret societies. Secret society membership therefore cross-cut kinship groups in communities. In addition to serving as an overarching organization for the wider community, there is ample evidence that major secret society ceremonies included members of neighboring villages or even of larger regions. In the Bella Coola region, secret society members in one village could even intervene in another village’s affairs to punish ritual transgressions. The marking of initiates with scars or other physical modifications may have been used to reliably identify initiates when they visited groups where they were unknown.

Given such mutual participation in secret society rituals on a regional scale, it is not surprising that the masks and other ritual paraphernalia (rattles, staffs, feasting dishes) exhibit artistic similarities generally known as the Northwest Coast art style with regional substyles (e.g., Kwakwakawakw (also known as the Kwakiutl), Salish, Nuuchahnulth (also known as the Nootka), Tlingit, Bella Coola, Tsimshian). These ritual and artistic similarities can be considered as expressions of a Northwest Coast Interaction Sphere. In addition to common secret society ritual origins, these similarities also undoubtedly emerged from common feasting and political structures.

Power Animals

One of the features of these common ritual practices was an emphasis on certain animals as sources of great power. These included bears in particular (Fig. 2.5), but also wolves, various birds (especially ravens and eagles), mythical animals such as sea monsters (especially the sisiutl and thunderbirds), and killer whales.

2.5 A bear head used as a patron in Bella Coola rituals and made to act life-like during ceremonies.

Number of Societies and Proportion of Population

While some communities may have had only a single secret society organization, the more common pattern seems to have been for communities to have from two to five such organizations. As previously noted, some societies were exclusively for chiefs and thus must have involved only a small segment of the population. Other societies had up to forty-four or fifty-three individual dance roles, but it is not clear whether this was for a single village or whether it was for the regional organization. Some societies like the Nuuchahnulth Wolf Society were for all free male residents of villages at the entry level, although the upper ranks only involved small numbers of people.

Sex and Age

Women could be initiated into at least some secret societies. They could perform dances in some societies, but only held supporting roles in others. There were also societies that excluded women or had exclusively female members.

Children were commonly initiated into many secret societies around the age of seven to ten years old. However, cases of three-year-old initiates were also reported.

Feasts

There were numerous feasts associated with secret society initiations and performances, even on a nightly basis for the duration of the ritual season. There were particularly grandiose feasts at the culmination of sons’ initiations into the most important societies, described as the greatest potlatch of a man’s career (Boas Reference Boas1897:205,208). Other feasts were given to secret society members for services, as fines for transgressions, and for various initiation arrangements.

Frequency

Important secret society dances and rituals were held every year during the winter ritual season. Initiations into the highest ranks must have been much less frequent since it took about twelve years to enter the third level of the Cannibal society.

Ethnographic Observations

Core Features

Motives and Dynamics

In addition to their ideological claims, Drucker (Reference Drucker1941:226) categorically states that the function of secret societies on the Northwest Coast was to dominate society by the use of violence or black magic. Accounts of some informants portrayed them as “terroristic organizations” (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:226). Members of secret societies were reported to experience powerful feelings of superiority over non-members (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:257). Ruyle (Reference Ruyle1973:617), too, argued that the monopolization of supernatural power by the ruling class supported the exploitative system by producing fear, awe, and acquiescence on the part of the uninitiated populace. In discussing the Gitksan, John Adams (Reference Adams1973:115) makes the important point that for those at the head of kinship groups, there was no way within the kinship system to increase wealth or power. In order to do this, ambitious individuals had to go outside kinship groups to create war or other alliances or to establish secret dance societies.

In general, Boas (Reference Boas1897:638) painted a very dynamic picture of secret society formation and evolution, showing that new dances were constantly being introduced, with some of the better ones lasting, while many faded away. Similarly, Olson (Reference Olson1967:67–8) observed that “new” dances (not necessarily secret society dances, but probably displaying similar dynamics) were considered great things and were often obtained from neighboring tribes by the Tlingit, namely from the Tsimshian, the Tahltan, and other Interior groups. Boas also observed that ceremonies that became too elaborate and expensive were abandoned for newer ones (Reference Boas1897:644), and that people who wanted to obtain the advantages and prerogatives that the secret societies could confer either had to join existing secret societies or start new ones (Boas Reference Boas1897:663).

Although the specific historical societies of the nineteenth century such as those with cannibal aspects seem to have spread widely along the coast in recent times (sixty to seventy years prior to Boas’ work), Boas (Reference Boas1897:661) argued that other forms of secret societies probably existed earlier. Thus, as elsewhere (the Plains, New Guinea, the Southwest, California), specific successful secret societies exhibited the ability to spread over large regions very rapidly, creating a relatively uniform regional network of ritual and political organizations that would otherwise be unexpected and surprising. In fact, Boas (Reference Boas1897) stated that all the secret societies of the Northwest Coast were very similar, often even using the same names. They all used cedar bark as badges, including head rings, neck rings, and masks. I postulate that the same dynamic probably underlay the emergence of regional ritual phenomena such as the Chavín Horizon, the Chaco Canyon culture, the Hopewell Interaction Sphere, or other similar prehistoric manifestations.

Wealth Acquisition (see also “Membership Fees”)

Little is written about how secret societies obtained material benefits. Certainly, the many feasts that the initiates’ families were required to give to the members of the secret societies (as documented by Drucker Reference Drucker1941) were major types of payments. The required training of initiates also necessitated payments, as did all instances of returning initiates back to normal states so that they were no longer a danger to the community (Drucker Reference Drucker1941). Initiation fees for Nuuchahnulth novices were given to chiefs who distributed the wealth items among society members (Boas Reference Boas1897:632). Anyone who coughed or laughed during Kwakwakawakw ceremonies was required to give secret society members a feast (Boas Reference Boas1897:507,526).

Halpin (Reference Halpin and Seguin1984:283–4) says that Tsimshian chiefs in secret societies were richly compensated for their passing of power to novices. The form of “payments” is far less specific, although the surrender of wealth for the transfer of dances, songs, prayers, or paraphernalia is plausible. The cost of advancement into successive ranks escalated in tandem with rank level. While the individual initiate may have personally financed some of these costs as he matured, it is more likely that, as a member of a high-ranking administrative family in a corporate group, he drew upon his entire family, and probably his entire house group or kin group to provide the necessary initiation payments. In this fashion, secret societies could draw off substantial portions of the surplus production of a large section of a community.

Bella Coola and probably other secret society performers sometimes could attract and ensnare the spirit or soul of uninitiated spectators, who then had to pay to have their spirit returned to them (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:5,63). Similarly, Kwakwakawakw spectators who had their souls stolen by dancers had to pay to have them returned (Boas Reference Boas1897:561,577). In general, secret society members were thought to cause or promote sickness in their communities so that people would have to come to the society to be cured, and had to pay the “shaman” handsomely. This was viewed by the afflicted individuals as extortion (Boas Reference Boas1897:197,580,744; Drucker Reference Drucker1941:226fn76,227). Thus, successful secret society “shaman” curers were always wealthy (Boas Reference Boas1897:197,580,744; Cove and MacDonald Reference Cove and MacDonald1987:116,129).

Political Connections

The power of Bella Coola chiefs was said to derive from the performance of dances that they controlled in the Sisauk Society composed exclusively of chiefs (Barker and Cole Reference Barker and Cole2003:63–4). Chiefs were also the exclusive members of the Cannibal and other societies in many groups or were the heads of secret societies as among the Nuuchahnulth, Quinault, and Chinook (see “Exclusiveness and Ranking”).

Tactics

Ideology and Control of Esoteric Knowledge

Central to Northwest Coast secret society ideologies were putative ancestral contacts with supernatural beings who conveyed supernatural powers to specific ancestors who, in turn, made them available to those of their descendants who wanted those powers and were able to acquire them through memberships in secret societies. This required considerable wealth payments as well as family connections. In the conceptual schemes of secret societies, these supernatural powers could be accessed via initiations (involving fasting and physical-psychological ordeals), dancing and singing, donning masks and costumes, and using ritual paraphernalia. Members were said to become possessed by the spirits, or even to become the spirits (see “Ideology and Control of Esoteric Knowledge”). For instance, Kwakwakawakw dances were claimed to be inherited from the mythic encounter of an ancestor with a supernatural being that conferred power on the ancestor which subsequently could be passed on to one of his descendants (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:202). McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948a:238–40) observed that the Bella Coola Sisauk Society claimed to have very powerful supernatural connections which apparently increased with repeated initiations (up to ten times).

Among the Kwakwakawakw and Tsimshian – and probably other Northwest Coastal groups as well as Southwestern groups – the right to control economic resources, like the right to access specific supernatural spirits, was hereditary, with powers and privileges stemming largely from the exclusive elite hereditary rights and roles in secret societies (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:59; Adams Reference Adams1973; Cove and MacDonald Reference Cove and MacDonald1987:38; Wolf Reference Wolf1999:90). Exclusive access to supernatural knowledge and power was used as a warrant for the exercise of specific practical skills, and the differential wielding of secular power and authority. Tsimshian chiefs claimed that only they had the power to deal directly with heavenly beings, whereas such contact would make others go insane or make them sick (Halpin Reference Halpin and Seguin1984:286).

Typical of many transegalitarian societies, material wealth and positions of power were portrayed among the Gitksan, the Bella Coola, and probably most other groups as resulting from spiritual favor obtained through the performance of special rituals and feasts (Adams Reference Adams1973:119; Barker and Cole Reference Barker and Cole2003:164). A more extreme expression of this ideology was promulgated among the Bella Coola, some of whom maintained that humans could not do anything without supernatural help. Therefore sacrifices, prayers, and abstinence were needed for all important endeavors, perhaps to promote or justify an ideology of privilege since it was maintained that in order to use those skills, they had to be validated, typically at potlatches – hence rich families had many “skills” while the poor had few or none in this ideological system (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:57,104,110,261).

Power was portrayed as a gift from the spirits in recognition of an individual’s strong supernatural character and/or the ritual observances of an individual (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:522). The supernatural power held by “shamans” was claimed to be particularly dangerous to others and was sometimes even portrayed as a spirit residing in the body of a shaman (573,576). This presumably also applied to secret society members since shamans were generally members of secret societies and the same term (Kusiut) was used to refer to both a shaman and a secret society member (547,565). However, in contravention of all norms, powerful chiefs “feared no restrictions and heeded no conventions” (489), and undoubtedly justified their actions in terms of their positions in the Sisauk Society. Such actions and attitudes are characteristic of extreme aggrandizer, if not sociopathic, behavior (Hare Reference Hare1993).

In the ideology of the secret society, initiates went to the upper world to obtain supernatural knowledge and in some sense became supernatural beings. Boas (Reference Boas1900:118) added that initiates in the Bella Coola Cannibal Society took human flesh with them to eat on these celestial journeys, for which a slave was killed. However, supernatural power could also be transferred from one individual to another by means of “shooting” a crystal into the person who fainted or was “killed” by the shock of the power, but then was revived and eventually returned to a normal state by removing the crystal from his body. Supernatural power was portrayed as dangerous (rather like electricity or nuclear power), although secret society members knew how to get it and use it without harming themselves (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:4,36,74,80–1,165,247–8,251–2). According to Garfield and Wingert (Reference Garfield and Wingert1977:41), “recipients of secret society power were dangerous to all who had not been initiated by the same spirits.” At the time of European contact, the power held by secret society members was apparently unquestioned (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:10).

In order to emphasize the supernatural abilities of initiates, members of at least the most important secret societies adopted the title of shaman, apparently irrespective of their shamanic skills, not too dissimilar to the training of priests in seminaries. Among the Wikeno Kwakwakawakw, all the initiates and dancers in the shamans’ series of dances were called “shamans” (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:202). The same appears to have been true among the Nuuchahnulth (Boas Reference Boas1897:632). The Xaihais Kwakwakawakw distinguished between those called shamans by dint of membership in secret societies and “true shamans” (Boas Reference Boas1897:214). Among the Kwakwakawakw at Fort Rupert, Curtis categorized people as either uninitiated or “shamans” (initiates) (Touchie Reference Touchie2010:103). Similarly, Boas (Reference Boas1891:599) reported that those who were not initiated into the Wolf Society were referred to as “not being shamans,” while new members were initiated in the context of ceremonies and feasts referred to as the “Shamans’ Dance” (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1980:30).

In addition to bearing the epithet of “shaman,” Bella Coola initiates also wore a distinctive collar used by shamans (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:11). Tsimshian chiefs often incorporated references to “heaven” in their names, referring to the source of their power, and engaged in rival demonstrations to display their superior supernatural power.

Benefits and Threats to Community Well-being

A major benefit that secret societies claimed to provide to their communities was protection from dangerous supernatural powers which secret societies themselves periodically unleashed in communities to demonstrate how much danger the community might face without their protection. McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948b:58,71–90) observed that the Cannibal Societies of the Bella Coola not only commanded the most awe, but instilled fear and terror in non-members. Manifestations of non-human behavior inherited from ancestors and evoked by Kwakwakawakw possession dances included the raw uncontrolled power of supernatural entities that wreaked havoc in the material and social world via their possessed human agents. Demonstrations of this raw power involved the possessed person destroying property, tearing off people’s clothes, biting people, and cannibalism. Cannibal-possessed people ran through all the houses of the village biting various individuals, even those of high rank (Boas Reference Boas1897:437,440–3,528,531,635,651–6; Drucker Reference Drucker1941:202,213,216) or took “pieces of flesh out of the arms and chest of the people” (Boas Reference Boas1897:437). It was said that if the Hamatsa (cannibal) spirits could not be pacified (by dances and songs), then there would always be trouble (Boas Reference Boas1897:573,616). People who suffered injuries from such acts had to be compensated. The cannibals could become excited at any time if provoked by any perceived slight, the mention of certain topics, mistakes in rituals, or improper actions (Boas Reference Boas1897:214,557; Olson Reference Olson1954:242; Garfield and Wingert Reference Garfield and Wingert1977:41), thus posing a constant threat to individuals and the community (Fig. 2.6).

2.6 A diorama of a new Hamatsa initiate emerging from a ritual house screen, still possessed by the cannibal spirit. Note the roles of the women in the proceedings and the cedar bark rings worn by other members, indicating that they had control over the cannibal spirit.

Members of other secret societies like the Fire Throwers and Destroyers could similarly wreak havoc (typically destroying almost anything in their frenzies and biting off pieces of flesh from women’s arms – all of whom had to be compensated), and they regularly did so when they contacted sacred powers, only to be brought under control by the higher ranking members with the secret knowledge to control supernatural forces (Halpin Reference Halpin and Seguin1984:283–4,286,289–90). This was similar to the Panther dancers among the Nuuchahnulth described by Boas (Reference Boas1891:603) who knocked everything to pieces, poured water on fires, tore dogs apart and devoured them. McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948b:58,71–90,107,118,127) repeatedly mentions the terror that such events created throughout the entire village, especially for the uninitiated who often cowered in their houses or rooms while destruction rained down on their houses or persons from “Cannibals,” “Breakers,” “Scratchers,” “Bears,” “Wolves,” and other supernatural impersonators. As previously noted, other dancers claimed to capture or steal the souls of spectators (Boas Reference Boas1897:561,577; McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:5,63). Similarly, individuals being initiated into spirit dancing among the Coast Salish Sto:lo were considered dangerous, having unregulated power capable of harming others, whereas secret society members had the knowledge to control such individuals (Jilek and Jilek-Aall Reference Jilek and Jilek-Aall2000:5).

Among the central Kwakwakawakw, some of the most important claimed powers were the ability to heal or cause sickness or death (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:203) as well as the power to capture the souls of audience members and return them (Boas Reference Boas1897:561,577). The Nuuchahnulth had a secret society, largely composed of women, that specialized in curing (Boas Reference Boas1897:643) and this may be the same as the Tsaiyeq Society described by Drucker (Reference Drucker1951:217). The Quinault also had a secret society that was primarily for curing and whose members were primarily women (Olson Reference Olson1936:122). However, members of their main society, the Klokwalle (Wolf) Society, were feared and reputed to kill and eat people during their secret ceremonies (Olson Reference Olson1936:121).

One community benefit of some secret society dances that included volleys of rifle fire was that they could be used to strengthen warriors’ military spirits, excite them to go into battles, and presumably be more fearsome and effective warriors (Boas Reference Boas1897:577,641). As another community benefit, at least one dance, the Mother Nature Dance, of the Bella Coola was portrayed as creating or promoting the birth of plant life (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:196).

Exclusiveness and Ranking

In general, Drucker (Reference Drucker1941:225; see also Ford Reference Ford1968:24) noted that on the Northwest Coast, the highest ranking chiefs owned the highest ranked dances with the most ceremonial prerogatives. Low-ranked individuals were generally not members of secret societies and could not even participate in potlatches following dances.

Among the Tsimshian, “supernatural contacts were determined by hereditary status … only persons who had wealth could advance in the ranks of the secret societies” (Garfield and Wingert Reference Garfield and Wingert1977:46). Only elites were members of the exclusive Fire Thrower, Destroyers, and Cannibal societies (Halpin Reference Halpin and Seguin1984:283–4). Expensive secret dance societies excluded non-elite Gitksans, according to John Adams (Reference Adams1973:113)

Kwakwakawakw individuals had to have both a hereditary claim or affinal link (to be able to acquire dances) and enough family resource-ability to underwrite the training, displays, gifts, and impressive feasts required for initiation (Boas Reference Boas1897; Codere Reference Codere1950:6; Spradley Reference Spradley1969:82; see “Cross-cutting Kinship”). The Hamatsa members, in particular, were “men in the highest positions in all the tribes” (Spradley Reference Spradley1969:82). Thus, political and social positions of rank, hierarchical descent, and succession were all related to ceremonial titles and privileges (Wolf Reference Wolf1999:82). Dances were ranked, with only the highest ranked chiefs eligible to enter the Cannibal Society among the Bella Bella (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:202,205,208,216).

There was also a series of specialized roles in secret societies which were probably ranked. In addition to the numerous dance roles that were inherited and owned, Kwakwakawakw secret societies had masters of ceremonies; dance masters; caretakers for drums, batons, and eagle down; door guardians; tally keepers; distributors of gifts; people designated to be bitten; dish carriers; and undoubtedly many other offices (e.g., fire tenders, assistants, messengers) (Boas Reference Boas1897:431,541,613,629). McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948a:27,44; Reference McIlwraith1948b:44,50) also reported that some members of the Bella Coola Kusiut Society were calendar specialists who engaged in bitter disputes for ceremonies just as their supernatural counterparts “argue about their observations after the fashion of humans.” Other specialized roles included keeping track of debts which required training and involved the use of sticks to keep accounts (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:228). McIlwraith also mentioned carvers, heralds, singers, dancers, marshals, and spies in various accounts.

The Sisauk Society of the Bella Coola was explicitly viewed as an exclusive society of chiefs. Only children or families of wealthy chiefs could be members (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:180–1) and membership gave individuals a warrant for control over a territory derived from their confirmation of ancestral power (Kramer Reference Kramer and Kramer2006:80). The power of Bella Coola chiefs was said to derive from the performance of dances that they controlled in the Sisauk Society (presented in terms of their mythical ancestral heritage). Dances had to be validated by distributing costly gifts (Barker and Cole Reference Barker and Cole2003:63–4). Similarly, an ancestral prerogative was required for entering the Kusiut Society, and the leading roles of “marshals” were hereditary (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:16). Permission had to be obtained from the marshals of the society for all performances and “tricks” to be used. In concert, these officials approved new initiates, oversaw preparations for ceremonies, policed behavior, ensured that the dignity of the society was maintained, and decided on punishments (16,24,68,114,124,128–9,150). Their names reflected power roles (e.g., “Destroyer,” “The Terrifier,” “Dog-Tooth,” and “Ritual Guardian Who Grips with His Teeth”; 16–17). Aside from the role of marshals, there were other specialized roles, and dances were ranked in importance (123).

For the Tsimshian the cost of initiations into successive ranks escalated in tandem with rank level, thus creating very exclusive upper ranks (Halpin Reference Halpin and Seguin1984:283–4). Among the Nuuchahnulth, chiefs headed the Wolf (Lokoala) Society while only rich individuals became members of Coast Salish secret societies (Boas Reference Boas1897:632,645). Chiefs led the secret society of the Quinault and members had to be wealthy (Olson Reference Olson1936:121; Skoggard Reference Skoggard2001:6). Members of Chinookan secret societies were also from the upper class (Ray Reference Ray1938:89–90).

Membership Fees

Membership and advancement fees were explicitly used to restrict membership, especially in the upper ranks. Among most groups examined by Drucker (Reference Drucker1941:207–8,209,211,212–15,217,218,219–23) fees included a series of feasts or potlatches given by the initiate’s family and supporters to secret society members, or at least the higher ranking members, culminating in a large, expensive public celebratory feast. For the initiation of a chief’s son, a full year was required to assemble the necessary materials (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:214). The Nuuchahnulth only held the Wolf (Lokoala) ceremony when an individual could give “a large amount of property” for an initiation (Boas Reference Boas1897:633). This wealth was given to the head of the secret society who distributed it to the members at a great feast (Boas Reference Boas1891:599).

The total cost of the initiations into some of the Wikeno societies was very expensive, and the major potlatch given by high-ranking individuals at the culmination of a son’s initiation was usually the greatest of a man’s career (Boas Reference Boas1897:205,208; Olson Reference Olson1954:243,249). Full entry into the third level of the Cannibal Society took twelve years and required a great deal of wealth, with few men able to achieve this rank. The Heavenly series of dances of the Wikeno Kwakwakawakw were even more costly (Olson Reference Olson1954:205,213). Boas (Reference Boas1897:556) provided a partial list of items given away for initiating one man’s son as a Hamatsa, apparently not including the various feasting and potlatch costs. These appear to have been three coppers worth 3,400 blankets in all, plus a large number of blankets given to guests, including two button blankets. Elsewhere, Boas (Reference Boas1897:471,501) emphasized that initiations involved immense wealth distributions, especially for Hamatsa initiation, which was “exceedingly expensive.” When a secret society dance was transferred from one Kwakwakawakw mother’s kin group to her son, a square 100 feet on a side was demarcated on the beach and filled with food dishes, pots, cutlery, bracelets, boxes, blankets, copper, canoes, sea otter pelts, slaves, and other wealth items to be given away (Boas Reference Boas1897:422,471). The main wealth items that Kane (Reference Kane1996:165–6) mentioned were slaves, otter furs, dentalia, and wives. Initiations were one of the few events in which wealth was purposefully destroyed (Boas Reference Boas1897:357). Spradley (Reference Spradley1969:92) also emphasized the excessive costs of initiations and feasts, listing gold bracelets and broaches as given to guest chiefs from other villages in addition to copious amounts of money, clothes, blankets, dishes, pots, and other items given to helpers. Boas (Reference Boas1897:542) mentioned that at one initiation, women and children were given coppers, bracelets, and spoons, while men received silver bracelets, kettles, and box covers. At another initiation, 13,200 blankets were given away as well as 250 button blankets, 270 silver bracelets, 7,000 brass bracelets, 240 wash basins, and large quantities of spoons, abalone shells, masks, and kettles (Boas Reference Boas1897:622–9).

Initiation into the Bella Coola Sisauk Society was similarly expensive, although actual amounts of goods are not reported by McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948a:198,203–5,207,238–9) who only said that gifts were given to the village and “foreign guests” who received potlatching valuables. He also stated that paying for people to care for initiates in seclusion was a high expense, and that chiefs’ sons could undergo repeated initiations (up to ten times) to increase their prestige in the society, with high costs each time. Costs were in the form of skins, blankets, food, boxes, baskets, slaves, canoes, and unspecified other items (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:203–5).

Initiation into Chinookan secret societies required the assembling of wealth over a period of several years for the formal initiation and to pay mentors for their instruction. This generally imposed “a considerable burden on the initiate,” amounting often to an equivalent of US$200 (in 1938) (Ray Reference Ray1938:90).

The Coast Salish initiations were similarly described as “very costly” (Boas Reference Boas1897:645). Olson (Reference Olson1936:121) claimed that there were no high fees for joining the Quinault Wolf/Klukwalle Society. This seems anomalous.

Public Displays of Power and Wealth

McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948b:4,10) stated explicitly that the prestige of the secret societies was derived from their ability to inspire awe, and that they all worked together toward that end, including promoting the ideology that members were supernaturally powerful and dangerous, and killing slaves to reinforce these claims (22). As a result of these and other tactics, when Europeans first encountered Northwest Coast tribes, the power of secret society members was described as “unquestioned.”

Secret societies used public performances of supernatural powers to create awe and fear, supplemented by physical coercion to consolidate their claims of power and make them tangible and effective. New initiates into the Bella Coola Sisauk Society obtained “strange power” and acted “peculiarly” and “crazy” due to the possessing spirit (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:198). Such descriptors seem understated given the more graphic accounts of cannibalism, biting people, devouring live dogs, disemboweling dancers or beheading them or burning them or drowning them (all of whom were subsequently brought back to life), and demolishing house walls and furnishings (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:7,107,128). The public was allowed to watch many of these performances, sometimes standing by the doorways of host houses or witnessing performances that were routinely repeated in each house of a village (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:7,27,47,55,58,211). Destruction of property only took place during the initiation of a son into a secret society or for taking on a new role or building a house (Boas Reference Boas1897:357). The possessing spirit was subsequently expelled from the dancer by society members at the end of the ceremony (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:239; Reference McIlwraith1948b:62).

Some of the “tricks” used in society performances included making objects disappear, making suns and moons move over the walls by themselves, and throwing dog carcasses up in the air where they disappeared (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:112,165,223,226). In conjunction with the Kusiut Society, shamans gave a public feast at which they demonstrated some of their supernatural abilities. These included changing water to blood or birds’ down; pulling birds’ down from fires; burning stones; making water disappear; and throwing a stick up in the air to the ridge pole, and hanging from the suspended stick (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:565–7).

Kwakwakawakw dances resulted in a spirit possession of the dancer, giving the dancer miraculous powers, often displayed in the possession dances or exhibited by inhuman behaviors or supernatural powers, including power over pain. Dancers were then returned to normal states through the use of other members’ ritual knowledge (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:202). The supernatural power was derived from a member’s ancestor who had been possessed by a supernatural being who taught the ancestor the dance and gave him miraculous powers. However, such contact with the spirits could only occur during winter ceremonial events (Drucker Reference Drucker1941; Boas Reference Boas1897:393,418). Ancestral powers included the ability to stand on red-hot stones, handle fire and put coals in one’s mouth, throw fire around, walk on fire, walk on water, make stones float, make a rattle dance by itself, disappear into the ground or plow up the floor from underground, gash oneself, push an arrow through one’s body, swallow magical sticks until blood flowed, be scalped while dancing, be speared, bring a dead salmon back to life, commit suicide by throwing oneself into fire or by cutting off one’s own head and then being brought back to life, split a dancer’s skull in two and then revive them, engage in cannibalism, and eat live dogs (Boas Reference Boas1897:466,471,482,558,560,567,600,604, 635–7; Drucker Reference Drucker1941:204,211,214,218,220; Olson Reference Olson1954:240–1). Some members of the Nuuchahnulth curing society, the Tsaiyeq, were reported to be able to stick a feather in the ground and make it walk around the floor, to handle hot rocks, or put red-hot rocks in their mouths (Drucker Reference Drucker1951:215–16). One of the most remarkable accounts is of Chief Legaic who found a look-alike slave and had him act as Legaic in a performance. The slave impersonating Legaic was then killed and cremated as part of the performance, after which the real Legaic rose miraculously from the burial box containing the slave’s ashes (Halpin Reference Halpin and Seguin1984:283–6).

Other dramatic effects related more to economic and political power (associated with supernatural power) included the killing of slaves (viewed by the Bella Coola as necessary to accompany the novice on his spirit journey) and pouring fish oil on indoor hearths so that the flames reached the house roof, which sometimes caught fire (Boas Reference Boas1897:551,636,649,658). The possessing spirits also conferred success in hunting and war (Boas Reference Boas1897:396).

People could attract, control, and exorcise spirits by being initiated into the society and via the use of special dances and songs (Boas Reference Boas1897:431; Loeb Reference Loeb1929:273). The death and resurrection of initiates or others was a common theme (Loeb Reference Loeb1929:273). Jonaitis (Reference Jonaitis1988:147) summarizes a number of other staged displays of supernatural power described by Boas for the central Kwakwakawakw. Among the most important claimed powers was the ability to heal (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:203) as well as the power to capture (and return) the souls of people in the audience (Boas Reference Boas1897:561). Public processions of Hamatsa members and dancers were conducted through the villages to the ceremonial house, with “all the people” witnessing at least parts of the initiation (e.g., exorcising of the cannibal spirit), performances, dances, and feasts in the ceremonial house, although other dances and ritual performances were only for the initiated among the Nuuchahnulth and Kwakwakawakw (Boas Reference Boas1897:436,514,626,628,633,639,645; Spradley Reference Spradley1969:89).

For the Bella Coola and Tsimshian, non-initiates were admitted to some dances but had to stand by the door (Boas Reference Boas1897:649,659). Both male and female Nuuchahnulth initiates led a public procession showing off bleeding cuts on their arms and legs (Boas Reference Boas1897:634; Ernst Reference Ernst1952:18). Blood also streamed from initiates’ mouths (Boas Reference Boas1897:633), a tradition reminiscent of many Californian practices (Chapter 3) as well as Chinookan practices (Ray Reference Ray1938:90). Nuuchahnulth initiates were “killed” by putting quartz crystals in their bodies. They were subsequently revived when the quartz was removed (Boas Reference Boas1891:600; Drucker Reference Drucker1951:218), a practice resembling the Midewiwin and Plains secret society traditions (Chapters 5 and 6).

Ernst (Reference Ernst1952:76,79) reports Nuuchahnulth performances that could be publicly witnessed from individual houses and were performed almost continuously at different houses during the ritual season, although in the past spectators were only permitted to watch from inside their own homes. There were also Wolf Society performances by new and older initiates that publicly took place on the beaches in front of villages (Ernst Reference Ernst1952:25). In addition, a general feast was held which was supposed to be open to everyone in the village after initiations. Whether this was the same as the “Shamans’ Dance” reported by Kenyon (Reference Kenyon1980:30 citing Clutesi 1969) is not clear, but seems possible, since Clutesi attended this dance as a child in a large smoky house filled with costumed dancers, endless feasting, and dramatic performances which lasted for twenty-eight days and nights during which the Wolf Society initiated new members. The Shamans’ Dance was hosted by an important chief who only provided one such event in his lifetime.

The public was usually invited to witness the performances of the Quinault Wolf secret society. Performers entered into “frenzied states” in which they performed prodigious feats of strength, imitated their animal guardian spirits, cut their skin, skewered their flesh, pierced the flesh of their abdomen with knives, ate live coals, and tore dogs apart to eat them (Olson Reference Olson1936:121–2). While non-members were able to watch these performances, some people feared to attend them. The woman’s secret curing society also held public performances in which they washed their faces with whale oil without harm and “shot” novices with balls of dried salmon, causing them to fall down as if dead, and then revived them. Performers of the curing society paraded through the village in full dancing costume to the potlatch house where people, both men and women of the home village as well as visitors, were assembled to watch (Olson Reference Olson1936:126).

Chinookans also demonstrated their spirit power through dramatic magical performances such as walking on fire, standing in the middle of fires, slashing arms, or plunging daggers through their skin with miraculous instantaneous self-healing. These were openly viewed by the public, although some performances took place in houses restricted to members only (Ray Reference Ray1938:90–2).

Sacred Ecstatic Experiences

Comparative studies have identified a wide range of well-known techniques for inducing altered states of consciousness and sacred ecstatic experiences (SEEs) (B. Hayden Reference Hayden2003:63–73). Some of the more common techniques include severe physical trials such as fasting, sensory deprivation, prolonged dancing or drumming, use of psychotropics, auditory or visual driving, strong emotional perturbations including being “shot” or “killed” or forced to consume human flesh. Except for the use of psychotropic substances, all these techniques were used on the Northwest Coast.

As Loeb (Reference Loeb1929:249) observed, death and resurrection constituted one of the leitmotifs of most secret societies. Typically, the possessing spirit took the initiates away, killed them, and returned them initiated and reborn, as with the Nuuchahnulth Lokoala (Wolf) Society and Kwakwakawakw societies, which had to remove a piece of quartz from a “dead” initiate in order to revive him (Boas Reference Boas1897:585–6,590,633,636). Nuuchahnulth initiates were described as entering into states of “mesmerism,” while Coast Salish novices went to the woods for “inspiration” (Boas Reference Boas1897:639,646). Tsimshian, Wikeno, and Xaihais initiates into the Heavenly or Cannibal series of dances were supposed to have been taken up into the sky during their periods of seclusion, and were subsequently to be found on the beach (see Fig. 2.3) when they fell back to earth (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:206,214,220,221; Halpin Reference Halpin and Seguin1984:283–4). For the Kwakwakawakw, the primary goal of the winter ceremonies was to bring back youths who were in ecstatic, wild states while they resided with the supernatural protector of their secret society. New initiates into the Bella Coola Sisauk Society obtained “strange power” and acted “peculiarly” and “crazy” due to their possessing spirit (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:198). Kwakwakawakw performers entered into “frenzied states” in which they performed prodigious feats, imitated their animal guardian spirits, and supposedly injured themselves (see “Public Displays”) (Olson Reference Olson1936:121–2; Kane Reference Kane1996:146). Youths had to be returned to a normal psychological and social state by exorcising the possessing spirit (Boas Reference Boas1897:431).

Long seclusion and fasting periods were most likely used to induce ecstatic states. Typically, training and trials for initiations occurred at some distance from villages, in the “woods,” over periods varying for the Kwakwakawakw from one to four months during which initiates subsisted on starvation diets to the point of becoming “skin and bones” (Boas Reference Boas1897:437). The Tsimshian initiates at Hartley Bay spent from four to twelve days secluded, the longer periods being for the highest elite children (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:203,212,221–2; Mochon Reference Mochon1966:93). Initiates into the main Tsimshian “Shamans’” dance series were sequestered for a month or two “in a hut or cave in the bush surrounded by corpses” (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:221 – emphasis added). That these initiations involved serious physical stresses (undoubtedly meant to promote ecstatic experiences) is indicated by claims that “many people have died from them” (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:221; Boas Reference Boas1897:600; see also McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:40,75fn,81,108,138,254; Jilek Reference Jilek1982:84). Long seclusion periods (weeks, months, and sometimes years) tend to typify initiations into secret societies, especially for the wealthy elites as with the Bella Coola (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:184,203–5,207,372), the Tsimshian, and the Kwakwakawakw previously noted.

Initiates into the Wolf Society (Klukwalle) spent five days in darkness (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:121). Boas (Reference Boas1897:482) even reported the suspension of Tox’uit dancers by ropes inserted under the skin of the back and legs, in a fashion resembling the Sun Dance rituals of the Plains Indians, which must have involved altered states of consciousness.

Initiation into Chinookan secret societies included a spirit quest in which novices fasted and learned to inflict self-tortures followed by miraculous recoveries. Fasting was also part of the three-day initiation into the secret society (Ray Reference Ray1938:89).

Enforcement

In general, Ruyle (Reference Ruyle1973:617) argued that the monopolization of supernatural power by the ruling class functioned to produce fear, awe, and acquiescence on the part of the uninitiated populace and supported an exploitative system. There was a wide range of tactics used to intimidate, persuade, or coerce people into compliance with the professed ideological claims, rules, and actions of secret societies, but foremost among the tactics used was terror. Drucker (Reference Drucker1941:226) categorically stated that the function of secret societies on the Northwest Coast was to dominate society by the use of violence or black magic. Accounts by some informants portrayed them as “terroristic organizations” (Drucker Reference Drucker1941). People who transgressed the “laws of the dance” could be murdered, an apparently common occurrence. “When they heard a dance was to be given, the low-rank people all began to weep, for they knew someone would be murdered” (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:226). In addition, when disagreements broke out among members, even high-ranking individuals could be targeted by the society (Drucker Reference Drucker1941). In general, the use of masks to impersonate spirits constituted the “secret” of spirit appearances, so that if any uninitiated individuals saw a mask being carved (thereby revealing the real non-spirit nature of the masks), they were killed (Loeb Reference Loeb1929:272). On the other hand, some of the secret society initiations involved the public removal of a novice’s mask (e.g., Boas Reference Boas1897:626,628). Thus, the claim that secrets were revealed by knowing that the masks were not literally supernatural beings may have been more a pretext for terrorizing non-initiates.

Summing up the situation among the Kwakwakawakw, Boas (Reference Boas1897:466–9) noted that the enforcers of Hamatsa Society laws (mainly the Grizzly Bears and “Fool Dancers”) threw stones at people, hit them with sticks, or even stabbed them or killed them for any transgressions of ceremonial rules (see Fig. 2.4). Even people who coughed or laughed during the ceremonies had to provide a feast for the secret society members (Boas Reference Boas1897:507,526). Secret societies also organized raiding parties, engaged assassins, and regularly threatened to kill members who divulged society secrets or killed non-members who trespassed into areas used as special meeting places or for ritual events, or even saw some of the sacred paraphernalia, thereby learning some of the secrets of the societies (Boas Reference Boas1897:435; see also McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:177–8; Reference McIlwraith1948b:18,263; Halpin Reference Halpin and Seguin1984:287–8). Anyone revealing society mysteries among the Coast Salish was torn to bits (Boas Reference Boas1897:645,650).

For the Nuuchahnulth, Ernst (Reference Ernst1952:13,64–5,67) reported that people who “abused” the secret rituals were put to death within living memory, and that those who laughed during ceremonies had their mouths torn down from the lip outward. Anyone who revealed the ceremonial plans for the Wolf Society ceremonies was severely punished. Even those who broke activity taboos or initiates who failed to wear black markings on their faces for the year following initiation were punished (Ernst Reference Ernst1952:68,79).

Among the Bella Coola, Drucker (Reference Drucker1941:220fn49) observed some instances of members who carried clubs apparently acting as dance police, while McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948a: 192–3,266; Reference McIlwraith1948b:11,16,32,36,68,200,203,258–9,262) frequently mentioned that anyone responsible for divulging the “secret” that the masked performers and performances were not really visitations and miraculous acts of supernatural beings would be severely punished, frequently with death, whether the offending act was accidental or intentional. Blunders by dancers or failures of dramatic stage effects used in performances (which revealed the true nature of the performing “spirits”) similarly resulted in killing the offender(s) or the offenders having to redo the entire ritual, including all preparatory feasts and expenses (Boas Reference Boas1897:433). Anyone contravening society rules, including sexual prohibitions, revealing society knowledge, showing any disrespect, diminishing the integrity of the society, intruding in designated sacred areas, or talking/coughing/laughing during a performance, was also punished. If new initiates did not say the required phrases, they and their families could be killed (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:39). Most of these observations were substantiated by Boas (Reference Boas1897:417,433,645,650). If the act was egregious, secret society members in other villages could even attack the village where the offence occurred, presumably because the members in surrounding villages were closely connected and it was considered threatening to their own claims to supernatural connections and power (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:192–3,266; Reference McIlwraith1948b:18–20). Kusiut members were especially eager to recruit sorcerers who could kill individuals by supernatural means (probably using the power of suggestion) since they often relied on such means to kill offending individuals (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:695–9,740). In addition to policing the most obvious offenses, secret societies also enlisted a number of young “spies” to identify doubters in the community and to deal with them (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:14).

Tsimshian individuals who broke the “laws” of the societies were killed, while, as with most other groups, death was threatened for unauthorized people trespassing near ritual locations or into secret society rituals, especially if they discovered the “tricks” used in demonstrations of supernatural powers during performances (Halpin Reference Halpin and Seguin1984:287–8). Tsimshian technical assistants could also be killed if they botched special supernatural effects so that the supernatural display became apparent to spectators as an artifice. Halpin reports one incident where an entire crew of technicians committed suicide rather than face their fate at the hands of the elites after one such effect failed. According to Garfield and Wingert (Reference Garfield and Wingert1977:41), “recipients of secret society power were dangerous to all who had not been initiated by the same spirits.”

The initiates to the Xaihais Kwakwakawakw Cannibal Society were told:

Now you are seeing all the things the chiefs use. You must remember to take care not to reveal the secrets of the Shamans [society members]. You must abide by the rules of the work of the chiefs. These things you see before you will kill you if you break the rules of the dance. If you make a mistake your parents will die, all your relatives will die.

The use of power to kill transgressors of society “rules” was viewed as “evil” by at least some community members (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:221; also A. Mills, and Maggie Carew, personal communication). Among the Owikeno Kwakwakawakw, Olson (Reference Olson1954:217,234,240,241) reported similar killings or beatings for breaking the rules of the dances.

The Quinault punished smiling and laughing during their secret society performances by painfully deforming the offender’s mouth, dragging him or her around the fire by the hair, gashing their arms, and blackening their face. Snoops or intruders into their ritual preparation room were reportedly killed (Olson Reference Olson1936:121–2).

Cannibalism

Whether cannibalism existed in secret societies on the Northwest Coast or not is a contentious issue. Drucker (Reference Drucker1941:217,221–2) reported that Xaisla Cannibal Society members pretended to eat bits of corpses, giving pieces of flesh torn off to their attendants who concealed them, while among the Tsimshian a corpse was given to each Cannibal Society initiate at a mummy feast. Olson (Reference Olson1954:245) recorded conflicting opinions as to whether human flesh was actually eaten or only held in the teeth among the Wikeno. Curtis (in Touchie Reference Touchie2010:109), too, was skeptical that actual cannibalism took place, although George Hunt (Boas’ main informant) affirmed its existence.

Among the southern Kwakwakawakw, Boas (Reference Boas1897:439–41,649,658; also McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948b:108) cited several eye-witness accounts of Hamatsa initiates eating human flesh as well as biting “pieces of flesh out of the arms and chest of the people.” He also recorded at least two cases of slaves being killed and consumed for Hamatsa ritual purposes.

Boas (Reference Boas1897:649,658) also reported cannibalism as part of Bella Coola and Nishga initiations or ceremonies. He added that initiates in the Cannibal Society took human flesh with them to eat on their celestial journeys, for which a slave was killed, half of which was eaten by members (Boas Reference Boas1900:118). However, McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948b:107) felt that this was done with stage props rather than real consumption of human flesh, except that he acknowledged that slaves were sometimes killed, possibly to make such claims more believable (108). He also reported that chiefs belonging to secret societies killed slaves and buried them in their houses in order to give more power to their Kusiut paraphernalia (22). The sacrifice of slaves was also recorded as a regular part of the Wolf ceremonies of the Nuuchahnulth (Boas Reference Boas1897:636) and was reported by Kane (Reference Kane1996:121–2,148–9) a half century earlier. Members of the Quinault Klokwalle (Wolf) Society also had a reputation for killing and eating people during their secret rites (Olson Reference Olson1936:121).

Material Aspects

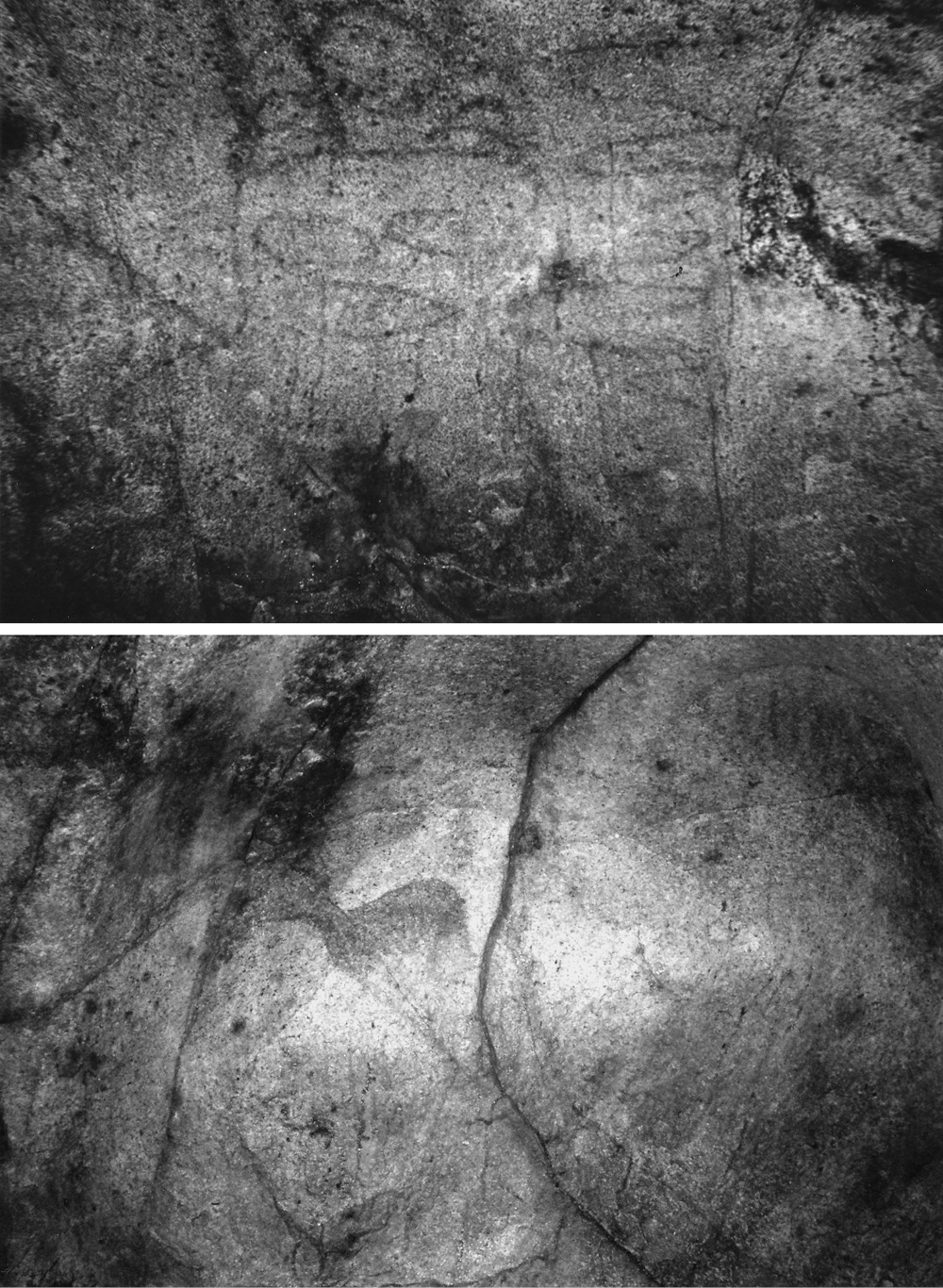

Paraphernalia

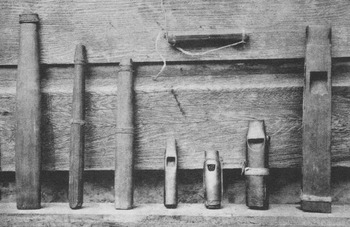

Whistles (Fig. 2.7) made of wood or bone were the voices of spirits or the voices of those possessed by spirits or signaled the arrival of spirits, as with most California groups, and whistles were often kept by initiates (Boas Reference Boas1897:435,438,446,503; Drucker Reference Drucker1941:210,213,216–18,221,222–3; McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:208,177; Ernst Reference Ernst1952:66–8; Olson Reference Olson1954:246; Spradley Reference Spradley1969:83; Halpin Reference Halpin and Seguin1984:290). A surprising variety of large and small whistle forms were photographed by McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948a:Plate 12; 1948b:28,36), who even recorded one (not illustrated) blown by means of a bladder filled with air, held under the arm.

2.7 Various types of wooden whistles used to represent the sounds of spirits in Bella Coola societies on the Northwest Coast.

Masks were carved by secret society members and represented spirits, but were sometimes supposed to be burned after major rituals like those of the Cannibals (Boas Reference Boas1897:435,632–9; Drucker Reference Drucker1941:203–5,211,215; Olson Reference Olson1954:245) and after all Kusiut ceremonies of the Bella Coola, apparently in an attempt to keep the spirit charade a secret, although Sisauk members received masks to be kept after their initiation (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:238–9; Reference McIlwraith1948b:27–8). Masks were normally kept hidden among the Tsimshian, and only displayed or used during supernatural performances (Halpin Reference Halpin and Seguin1984:284,287–8). Masks used by impersonators of wolves in the Wolf Society of the Nuuchahnulth were “jealously guarded for a lifetime, and relinquished only at death to some duly appointed heir.” These were considered ancestral family spirit allies (Ernst Reference Ernst1952:66–8,91).

Weasel skins were worn by Bella Coola Sisauk members as an insignia of membership, while members of the Kusiut Society wore swan skins with feathers as well as cedar bark rings and head circlets. Some members wore aprons with deer hooves or puffin beaks attached (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:190; Reference McIlwraith1948b:37,39,45).

Rattles were used in secret society rituals, including some shell rattles used by initiates which were suspended by skin inserts. Other rattles were used to purify novices (Boas Reference Boas1897:438,497,532). Bird-shaped rattles were used by Bella Coola initiates in their dances (McIlwraith Reference McIlwraith1948a:206).

Bullroarers and drums signaled the presence of supernatural beings among the Koskimo (Drucker Reference Drucker1941:219) or were considered the voice of the spirits (Boas Reference Boas1897:610–11). Although Loeb (Reference Loeb1929:274) states that bullroarers were only used by the Kwakwakawakw, McIlwraith (Reference McIlwraith1948b:28,250) lists them as part of the Kusiut Society paraphernalia of the Bella Coola.

Copper nails were used by Kwakwakawakw initiates for scratching (Boas Reference Boas1897:538).