The Chairman (Mr S. W. Dixon, F.I.A.): Our discussion paper is “How Can We Improve the Customer’s Experience of Our Life Products”, prepared by the Risk and Customer Outcomes Working Party. This paper has limited actuarial theory, but is very important for two reasons.

First, customers need to understand our products, and we either have to explain them better or we make them simple enough for anyone to understand without a detailed explanation. The depth of understanding is moot. I do not understand how my motor car works, but I still drive it.

Second, the profession has a public interest requirement, which is core to its message and principles. We need to take a lead in explaining technical issues for the public interest and public good.

The opener, Mark Chidley, is from the Financial Services Consumer Panel. As a solicitor, Mark specialised in the law of banking and finance. From 2005 to 2015, he was a partner, and latterly a consultant, with DLA Piper. Mark has a deep understanding of corporate and retail banking, and a particular interest in finance in the small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) sector.

Since 2009, he has been a non-executive director of North East Access to Finance Limited, a company closely involved in access to finance issues for small- and medium-sized businesses in the north-east of England.

Given his legal, banking and access to finance experience, Mark aims to contribute to the issues facing SMEs, as consumers of financial services products, and because he is a member of the Financial Services Consumer Panel.

Mr M. Chidley (opening the discussion): I am grateful that the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA), through this working group, is looking at the question of improving customer outcomes and the customer experience of life products. Not a lot of people start with the consumer, though all businesses probably should do so.

I am also grateful to the working group for coming and talking to my colleague, Teresa Fritz, and me, both members of the Financial Services Consumer Panel, in particular in relation to the duty of care aspects of the paper, which I will come onto in a moment.

The Financial Services Consumer Panel is one of a number of statutory panels which the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is required to establish and maintain under the provisions of the Financial Services and Markets Act. We are independent from the FCA and anything that I say is not a view of the FCA; it is my view, but usually it is also the view of the Financial Services Consumer Panel.

First, this is a good piece of work and an enjoyable read. The candour which it demonstrates in relation to things that have gone wrong in the past is refreshing. It is by understanding the things that have gone wrong before, that we can have a hope of making things better in the future and addressing this issue of improving customer outcomes.

My focus is on four aspects from the paper: improving customer understanding; needs-based selling; ongoing assessments and wider communication; and then the duty of care.

My chair, Sue Lewis, is always keen that we set the tone by reminding people that being a consumer is not a job; being a consumer is a state.

Starting out with improving customer understanding; it is very closely linked to disclosure, and the consumer panel is sceptical about disclosure. It is a matter of quality not quantity, and that that applies both to the means of presentation as well as the content of information.

All consumer journeys are important; the paper identifies negative use cases, unhappy consumer journeys, as being really important in helping to identify what could go wrong. That is an important component of the work in relation to improving customer understanding.

The working group as it moves forward with this paper should also pay attention to the work that is going on in the wider financial advice arena and, in particular, the financial advice market review that has recently concluded.

Moving on to needs-based selling, the paper is proposing that there is a move away from what industry wants to sell to what consumers need to buy. That is a very important distinction to make. If this were applied across financial services, it would be revolutionary. If that were to happen, it could lead to a new approach to product design; that in turn would promote innovation which in turn would promote competition, which seems to be lacking from the wider financial services arena at the moment. Both of them are critical to achieving good consumer outcomes.

Ongoing assessment and communication follow naturally from needs-based selling. If you have sold a long-term product to somebody because you want to make sure they need it then from time to time you will need to touch base to make sure it is still an appropriate product. There is some good original thinking in the paper about that.

Who should be required to take the lead? The approach adopted at the moment is a hybrid with the customer being required to do something and the provider also. Being a consumer is not a job and therefore there may be a little bit more onus on the provider than perhaps the paper identifies.

In that context, I refer to two other pieces of research work that have recently been done. One of them is the role of demand side remedies in driving effective competition by Professor Amelia Fletcher (work for “Which?”). Although it is primarily driven at competition, it is relevant in a much broader context in terms of looking after the interests of consumers and improving consumer outcomes.

The consumer panel will soon be publishing some research that we have had carried out for us by Jonquil Lowe at the Open University in relation to consumers and competition. This focusses on competition because the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) last year did a market investigation into retail banking and SME lending.

The duty of care. There is an ongoing debate. The FCA in its mission tells us that it is going to put out a discussion paper. Everything that the FCA says tends to get delayed for one reason or another, so I am really keen that this debate is kept going by people like the IFoA as we wait to see what will happen.

For us, the duty of care is not about giving consumers rights of legal redress; it is a tool to improve culture within organisations, to contribute to a re-establishment of financial services firms demonstrating their trustworthiness so that consumers in the market can trust them once again. It is about prevention not cure. It is about doing the right thing and not spending a fortune on compliance making sure you are not doing the wrong thing. It is genuinely putting consumers at the heart of the financial services business.

The Chairman: I am now going to introduce the four working party members. Two are based in London and two in Munich.

First, Taahira Hussain, from Vitality. She is the capital management actuary at Vitality. As well as capital and solvency work, Taahira also manages the first line governance process from a product and actuarial perspective for the actuarial product and underwriting teams. Taahira Hussain has built up a wide range of experience across a comprehensive range of customer-related issues, including 3 years at Standard Life, where she worked within the Product Compliance Team to resolve issues relating to products which impacted customers.

Prior to joining Vitality, she spent 5 years working for Willis Towers Watson across a wide range of projects within life insurance, including the normal ones like product development, customer remediation, valuations and mergers, and acquisitions.

Kevin Francis is the Managing Director of Capita’s Remediation Service Business, which focusses on supporting organisations which deal with complaints, past business reviews and wider rectification issues. Kevin has spent the past 20 years working in the field of remediation. During that time, he has been involved in helping clients with many industry-wide issues across pensions, investments, insurance and, most recently, annuities. Prior to that, Kevin trained as an actuary within the pensions consultancy area, working for Mercers and Arthur Anderson.

The two Munich people are Chris Barnard, from Allianz. He is a senior actuary with Allianz SE in Munich, Germany, with nearly 25 years’ experience in the insurance industry. Chris has worked in the product development, pensions, finance and business steering areas with a current focus on customer value initiatives. Chris has held several overseas appointed actuary roles and is a member of the life research committee.

Catalin Jumanca is also from Allianz. He is an actuarial manager with Allianz in Munich, Germany. Catalin currently works in the product development area with special focus on savings and pensions solutions, and also covering other strategic topics such as bancassurance partnerships, customer value, product governance and business steering.

I will now hand over to them.

Mr K. A. Francis, F.I.A.: Our working party was set up in 2014 to consider how, as an industry, we might avoid some of the historic issues surfacing again in the future.

We have been able to draw from a broad range of experience and perspectives: from consulting, research and life insurance. We presented some preliminary thoughts at the 2015 life conference and have since worked on refining the research to a point where we are ready to present our ideas today and to start engaging in more formal discussions.

We start by looking at where things went wrong previously and what we can learn from some of these.

Over the past 20 years, complaints and remediation projects have cost the financial services industry over £40 billion, mainly from the pensions, endowment and payment protection insurance (PPI) mis-selling scandals. This is set to continue to grow, not least until PPI complaints comes to an end in late 2019, the recent FCA introduction of PPI time barring.

Looking back, we can draw a number of common themes out of these mis-selling scandals, which have generally been linked to a predominantly sales-based culture; remuneration of frontline staff that drove inappropriate behaviours, for example, target penetration rates on PPI sales; the product design, products were such that not all aspects of the product were appropriate for all customers; poor sales practices and processes; and finally there was weak regulatory oversight or sanctions.

Great strides have been made in addressing many of these themes, but it is not clear we have come far enough as an industry to avoid the cost of failure in the future.

In the United Kingdom, the FCA, in conjunction with product providers, has worked hard to help restore confidence in the financial services marketplace. Improvements have been made, including increased regulatory fines and enforcement action, which has resulted in a significant reduction in fines in the past 2 years. This is in part due to earlier intervention, a live example being the outcome of the recent thematic review carried out by the FCA into historical annuity sales practices. This has resulted in several firms now having to undertake a proactive back book review of customer sales ahead of complaints coming in.

Across the European Union we have also seen positive developments under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, the Insurance Distribution Directive and the Packaged Retail and Insurance-Based Investment Products (PRIIPS), including aims to improve customer protection in the insurance sector, remuneration aligned to incentivise distributors to act in the best interests of the customer with greater transparency on fees and charges and focus across the whole product life cycle, including ongoing assessment beyond point-of-sale. However, we still see gaps within the current regulatory framework that have not yet been fully addressed. They include increased focus on requirements to ensure that products on an ongoing basis continue to meet customers’ reasonable expectations and provide a fair outcome for those customers.

This also includes the introduction of annual statements, with a reminder of benefits, options and any guarantees.

The question remains, however, as to who pays for any future advice that is required to ensure that products continue to meet the ongoing needs of customers as their circumstances change.

Furthermore, the FCA recently announced its findings of its review into advice suitability. This showed that while over 93% of advice was found to be suitable, in only 53% of the cases was the level of disclosure associated with the advice deemed to be acceptable.

In our opinion, one of the reasons why gaps still remain in the current regulation is that customers’ expectations and outcomes are part of a complex and rapidly changing framework with multiple stakeholders across an often long-term product life cycle and customer journey.

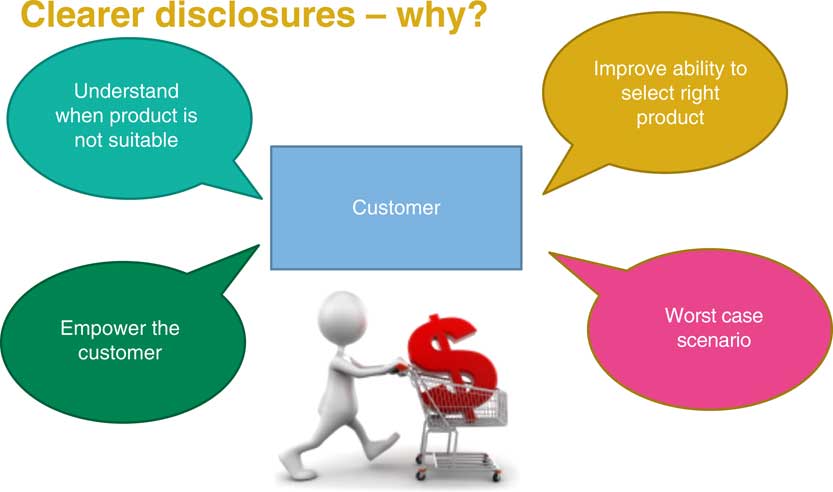

Figure 1 shows a simplified version of this landscape with our working party views concluding that, first, the end customers need to be placed at the centre of all stakeholders’ actions, behaviours, business models and culture. Products need to be able to evolve to ensure that they remain appropriate as customers’ needs change over time. Product design needs to become customer centric. Customers’ views need to be brought into the product design, sales and compliance guidelines. Products need to offer good value for money, while remaining simple and easy to explain with more emphasis on illustrations and “what-if?” scenarios that allow the customer to understand the risks inherent within the products. To this end the changing regulatory landscape is encouraging needs-based selling and ongoing assessment of product suitability.

Figure 1 Clearer disclosures – why?

We consider how we may go about improving customer outcomes in the future. Focussing on the United Kingdom, first, we suggest improvements in illustrations be shared with customers. These include scenarios, which need to move to be more forward-looking and regularly reviewed with consideration to interest and inflation and investment returns varying over the product lifetime, including negative as well as positive scenarios.

Thought should also be given to the risk return profile and any link with underlying volatility of the product and include the ability for tailoring illustrations to meet specific customer requirements or allow the customer time to interact across a range of scenarios in a dynamic fashion.

The next area is needs-based selling which at the simplest level can be broken down into understanding the customers’ value needs, and what the customer is getting in return for their premiums. Do the product features meet the customers’ needs in all circumstances? If not, then consideration should be given to rider benefits or optional elements. In some cases, customers should be advised that certain product features would not be appropriate, given the customers’ circumstances and needs.

Stress testing should be carried out to determine the circumstances whereby the products fail to meet the needs of the target market.

Next is understanding customers’ risk needs and then ensuring that the customer risk profile, or appetite, matches that of the product in question. This is followed by ongoing assessment of the product’s suitability throughout the product life cycle, which includes monitoring ongoing performance against the initial illustrations and continued assessment of whether the product is still meeting the customers’ needs, noting that these may have changed since the point of sale.

Bringing this all together we consider the duty of which Mark has already touched on in his opening statement.

Miss T. Hussain, F.I.A.: We will now consider the implications of our proposals.

Improving customer understanding has benefits all around. Up-to-date, clear and understandable disclosures will improve the customers’ ability to select the most appropriate product for their needs. This will also improve the customers’ understanding of key product features.

There is scope to take this further. Illustrations can be used to define the worst-case scenario. This can be used to take the customer through a journey to explain what could go wrong. It could also provide an idea in which circumstances the particular product would not be suitable.

By setting out more information, you are empowering the customers. They can make a more informed decision with the freedom to choose whichever product they wish, and this in itself is a big step forward.

Moving on, let us consider the implications of needs-based selling. This is a way of avoiding poor customer outcomes, but this may have implications for the way that the product is sold. It is likely that the market would change. Either it may become more granular to deal with niche groups or providers may become more selective over the products that they offer or they might only offer generic products.

The other extreme is where providers will unbundle products to match individual specific needs and drive innovation in the market through this.

In practice, though, meeting the needs of a customer is likely to be dictated by product features and flexibility. Complex needs often require more complicated solutions, yet products still need to be flexible to meet evolving needs.

This challenge should be at the top of any product development and sales capture to ensure that we can meet the needs of our customers in the best way.

That said, much of this depends on the distribution channel and ensuring advisers are on board. This does raise the question about what responsibility does the manufacturer have for distributors when following a needs-based selling approach.

It is likely that manufacturers will need to set up and be more proactive in monitoring and controlling distribution to ensure the standards are met. We also need to make sure remuneration is appropriate, and we believe that remuneration based solely on sales volumes will be replaced and incentives will be linked to customer service quality and ensuring needs are met.

Ongoing assessments are a key part of the thinking that we have done. We believe that one-off irreversible decisions to buy a product should be avoided. Instead, products should continually meet the needs of the customer, and those needs should be reviewed on a timely basis to ensure the products remain suitable.

There needs to be a clear link back to the product development stage. If we do not know our target market and the needs and value proposition are not clearly defined, then it will be near-impossible to monitor good outcomes.

The responsibility for a regular review and suitability assessment can fall to the company, distributor or the customer. The working party believes that this burden should be shared between the insurer and the policyholder, and this is an area for further consideration and research.

As an industry, we are moving in the right direction, but we can do more particularly with the advice gap that exists.

Mark described the duty of care as an opportunity to ensure firms act with the best interest of customers. Currently, what the industry is missing is a means of demonstrating that we are working with the right intention, particularly in light of the mis-selling scandals that Kevin mentioned at the start of our presentation.

The ideas behind duty of care are not new; but there are implications. A legal duty of care may appear more onerous but it may in fact reduce legislation. On the other hand, a legal obligation on firms may well reduce product innovation and features and reduce the complexity of products which, in turn, will have knock-on effects for customers through limited competition which would ultimately affect price.

There would then be further knock-on effects for the industry and the government where the protection and savings gap would grow. The government may well need to step in to address this.

We believe that a duty of care will also open up opportunities. Firms can innovate and compete without the unnecessary red tape intended to achieve Treating Customer Fairly.

It would also introduce a level of trustworthiness in the market, which would lead to greater confidence in our products and opportunities for sales and development. Alternatively, we can choose to extend the actuaries’ code to drive the right behaviours rather than it being a legal obligation.

This is an area for future debate and discussion.

The consideration of risk and customers is part of a complex landscape with competing interests, functions and stakeholders. All of these issues are being widely debated within the insurance industry with the regulator moving us all towards greater transparency with more information for customers.

Introducing new regulation may distract firms from creating useful products and may not add enough value for the additional effort.

There is a need for balancing the impacts on firms, and this debate will keep going for a while.

Continuing as we are is not enough, particularly as we move into a world of more complicated products where more information may not necessarily solve the issue that the needs of the customer are not adequately aligned with the product sold.

However, the industry chooses to proceed, it is clear that ensuring the needs of the customers are met, and being able to demonstrate this, is a greater area of focus within regulations, and one that will benefit us all.

We want to make it clear that this is an incredibly complex arena, and while we do not have a magic bullet to solve all of the issues we raise, the ideas we present demonstrate our goal of how customers’ understandings and outcomes could be improved.

We look forward to continuing to make a contribution in some of the key areas around treatment of customers, value for money and the concepts of duty of care in the near future. The working party hopes that the ideas presented will help firms to take that leap forward.

The Chairman: I will now open the discussion to the floor.

Mr J. G. Spain, F.I.A.: What surprised me in the paper was that, although during this meeting and in the paper the word “innovation” is mentioned, there is no mention of “insure tech” or “competition”. Yet, how many life offices in the United Kingdom have there been over the past 30 years? 100? 150? Different sizes; big ones, small ones. You have the advertisements on Daytime television, “Give us £50 a week, or whatever and we will give you £25 back at the end”. People think that that is a wonderful deal “because you will get all your money back”.

The truth is that not only do people not understand guarantees, which are expensive, but also people do not really understand flexibilities, and they are also expensive. Are the big profit-making insurers really willing to give up some of that profit in the hope of keeping some of the customers satisfied in the future? I do not think so. Competition needs to be reinvigorated.

Miss Hussain (responding): Competition is in two parts. On the one hand, companies are trying to generate profit; and on the other, they are competing against all sorts of markets. You have new entrants coming into the market. You have to drive something new and make them want your products.

We have been stuck in a world where people take out life insurance for their mortgage and we do not think about it much more than that. Their policy is put in a drawer for 20 years and it is hoped will never be needed. That is not really good enough.

If we, as an industry, drive innovation, we create great products that people actually want, we will be driving that competition for ourselves, which is the real challenge here. There is a lot of consolidation in the industry already and that has been driven through capital primarily. The onus is on each and every one of us to do our part and to take the challenge that we have presented and take that leap forward.

The Chairman: There is also a concern about an imbalance between the customer and the provider, as the provider knows far more than the customer. Therefore, competition is always going to be imperfect and the paper tries to deal with that.

Ms T. E. Burton, F.I.A.: You mentioned there is a need for manufacturers to get more closely involved in the distribution to break down these issues. What kind of ideas and themes have you have explored around that topic?

Miss Hussain (responding): We were thinking it was more as a manufacturer. You develop this great product, then you put it out there for IFAs to sell, and they may not necessarily be targeting your products at the right people. So it is trying to work out a way of pulling those distributors back into line with the way that you think.

Whether that is through in-house sales teams or, maybe, going out and training people more and taking more active responsibility, not just throwing commission at the problem, but actually taking a step forward and saying: this is my product and I need to make sure that it is being sold to the right people.

It may be that after you sold the product you may do more after-sales analysis looking at the target market that you have actually sold the product to, and seeing how that is working and maybe then taking a step back and saying whether that is right or not.

There are many things that we can do but I know we are not doing enough at the moment.

Mr B. C. Horwitz, F.F.A.: You said, Taahira, that the burden of ongoing reviews should be shared between policyholders and providers. That is an interesting statement. I would have thought that they are the two parties least capable of doing an ongoing review. It is a bit like a patient being told: why don’t you and the drug manufacturer get together to think about whether your drug is right for you? I would have thought an independent person, a doctor or a pharmacist, is a far better person to do that. Do you want to pick up on that point and tell us what you were thinking?

Miss Hussain (responding): We introduced this at the Life Conference a couple of years ago and had mixed feedback from the audience. We were thinking that when the customers bought something they need to understand what and why they have bought it. There are things that you can do: maybe prompt them on anniversary statements; put in paragraphs within the letter asking customers whether they remember why they bought the product and if anything is different from their current circumstances to come forward.

In that way the manufacturer is taking that step to tell them what their needs were and why they bought the product. It is then up to the customer to step up and say yes or no.

It is not possible to hold the customers’ hands for the whole journey. They also need to take some responsibility for what they have bought. There is a huge education piece that is generally missing in society, and that is going to take time to plug. In the meantime, there are small things that we can do within cost constraints. You can make them bigger but the bigger you go, the more expensive these things are.

Mr S. D. Hicks, F.I.A.: We need to be careful about expecting competition to be the panacea for everything. If we look at some other sectors, such as the gas and electricity sector, where the CMA has pushed switching, the outcome has been very few people actually switch even though it is easy to switch and they would pay less.

Moving to banking, again, the CMA has pushed switching there. Bank accounts tend to be more complicated but again not many people switched.

When you consider the more complicated world of life and pensions savings products, with their many different features, people do not switch easily, and the cost of switching is not obvious to people. That is probably equally true in the retail general insurance market. There is evidence that on annual renewal firms push up the price, because they have had low prices the first year to attract new customers. Again, there is a lot of inertia and people do not switch on renewal. I conclude you cannot expect competition to solve the problem. Can you explain to me why competition will be helpful?

Mr R. J. Gallagher, F.I.A.: I am currently in another working party which is focussing on the presentation of various risks to a consumer. Taahira referred to disclosures in her presentation and drew our attention to setting out what might be the worst-case scenario, and letting the consumer know.

I am interested to find out why that may be a good metric but also about whether the approach results in consumers focussing too much on the worst outcome, becoming a bit too risk-averse and then choosing not to buy products altogether.

Mr Francis (responding): Part of the current challenge is that if you do not tell your customers what the worst-case scenario might be and then the worst turns out to happen, you have got a potential mis-selling scandal on your hands. That costs a lot to put right, as we have seen in the past. Maybe it is not just around the extremes of scenarios but the likelihood of those happening.

It comes down to informing the customer about what the product does, when it works and when it does not work so that the customer has a better understanding of the product. It is not about scaring them in the first place.

Mr Chidley: I am now speaking with a different hat on as the purchaser of this kind of long-term protection product. There is a real risk that if I am shown that it is going to return 2%, 5% or 8%, then I have limited my thinking to an upside potential. So you have this quite granular upside potential but no mention other than in the broadest general terms that you might not get your money back and what could go wrong.

A little bit more honesty and focus may be a good thing but if you produce bad news to somebody who is about to buy a product, they may well then say: no it is too difficult and therefore not for me.

The paper is trying to suggest a more positive engagement, a more continuous engagement, between providers, advisers and end users or consumers, and it becomes a matter of balance. At the moment the balance is too much upside and perhaps not quite enough investigation of the negative possible downside risks. Most consumer advocates feel that generally, and in financial services in particular, this is an area that needs a little bit more thought.

The Chairman: Key Investor Information Documents (KIIDs) are now going to have that on them because they have four projections: not terribly good; what we think is probable; a really good outcome; and a really appalling stress test outcome.

The key thing is going to be the wording around that, and also how that is explained to the customer. It could easily be “ignore all these, just go for the top one”. That could be the thing that is explained.

Mr Spain: Trying to identify the worst-case scenario is going to lead to real problems, when in fact the worst case turns out to be twice or three times as bad as anybody ever thought, which is possible.

In defined benefit pensions, my area of expertise, I have come to the view that using discount rates is counter-productive. It hides more than it actually shows you, and instead we should be looking not so much at scenario analysis, but “what-if?” projections using, say, 10,000 scenarios, based upon robust analysis of what has happened in the past plus some expert judgement about how that might pan out in the future.

The Chairman: KIIDs is trying to project 10,000 times and come up with the mean, the high and the low outcomes.

The problems are the lack of data and using past data to project forward expectations.

Mr Spain: That is where expert judgement comes in.

The Chairman: Yes, you need some expert judgement to overlay. If interest rates are only going to be 1% for the next 100 years, what does that mean?

Mr D. J. Keeler, F.I.A.: Whilst I am quite supportive of the suggestion that so much information should be available to consumers, I am concerned about requiring the industry to provide this information on such a regular basis. I know it happens in quite a few industries: the banking industry sends me so many letters, I virtually throw them all straight in the bin.

I have stopped working now and so I have, as Stuart suggested, looked at switching energy companies. It is very simple. When I was working, I thought I could not the spare time to spend doing that.

When people buy our products, there is usually a catalyst, like buying a house. Five years later, there may be no such catalyst and they will get these letters through the post. How many do you think are going to be read, and how engaged is that consumer going to be?

What we need is to have companies that you can place your trust in. There are some operating in our market; but, as you have highlighted in some of the past scandals, that has not always been the case.

It is not enough to impose a duty of care and think job done. The consumer will not take any notice of that nor think any differently of the industry.

The Chairman: There does not seem to be any mention of any fundamental consumer research in the paper in terms of actually working out what the consumer wants. I asked my wife and she came up with the top 10 points that are in a KIID: I want to know the risk; I want to know what the likely returns are, both at the end and at the beginning and in a bad case and a really bad case; I want to know what the remuneration is of everybody involved in selling the plan to me, and the rest.

She then added “I also want to know what the impact is on tax and benefits. I want to know: am I going to pay more tax or am I going actually to lose benefits from taking out this product?” This has not been mentioned: has this been thought about? She then said that she wanted it all within two pages of A4, easily absorbed and diagrams not numbers.

Mr Francis: We did think about it and is part of the consideration of where we move things forward. We were engaging with the Life Board to consider whether they would fund some additional research; but decided to bring our paper for discussion at this point and then consider how we take it forward.

We are also looking to take forward and potentially host within provider groups, as providers have a strong interest in what their customers actually want.

Mr Chidley: There is quite a lot of generic consumer information and research that has already been done. These are driven by issues relating primarily to competition, and improving the customer experience. That is a good place to start and then seek funds to move forward.

Mr G. J. Yeates, F.I.A.: Many of the challenges seem to be similar to those faced in general insurance and selling general insurance products.

Have you spoken to any actuaries from that function in terms of your research or understandings of the products and problems?

Miss Hussain: Not yet. You are right that the issues cross the whole spectrum of the actuarial work that we do and is something that we will look at as part of the next steps.

Mr Horwitz: Coming back to the previous point about looking at the consumer perspective, you may not be aware but there is another IFoA working group which we started about 2 years ago looking at communicating risk to consumers – Communicating Investment Returns in the Retail Customer Journey. Gary Smith is currently chairing it. We have Bruce Moss involved as well. They have budgets to carry out some consumer research.

That brings me to my final point. The “so what for actuaries” point. This paper brings the question directly “but what can we do?” The challenge is, if we are so good at quantitative things, communicating risk and making financial sense of the future, how do we produce this miraculous two-page product description with diagrams and not one mention of the words “volatility” and “standard deviation”?

I would be interested in the view of the panel of what we, as individual actuaries, can do.

The Chairman: I had one question which was about remuneration. How do you measure customer service quality, ensuring that needs are met?

Miss Hussain: One of the things that I see quite frequently in my job are the complaints that come through. They cover a wide spectrum but it is generally a complaint because we, as a firm, have not met the expectations of a customer and their journey has not been what they wanted it to be.

If we are driving remuneration through ensuring good customer service, in turn we are going to reduce the number of complaints; we are going to reduce the amount that we are paying out through redress; and, it is hoped, improve the general opinion of our industry. That can only have advantages.

The Chairman: Is there any way of measuring positives as opposed to measuring negatives? Or does that work need to be done?

Miss Hussain: People are more likely to complain if they have had a bad experience. It may be possible after a sale to carry out a survey to get some feedback that way.

The Chairman: One other question: what is risk? I know that sounds a bit odd but PRIIPS suggests that risk is measured at the point of the assumed holding period, so you do not bother about what happens in between. But customers have a very different view, and IFAs have more diverse views.

What do you think we should be defining risk as for the purposes of these long-term financial products?

Mr Francis: From our perspective it is about whether the product performs as expected in the consumer’s eyes. What is the likelihood of it not performing? If it does not perform, what does that mean for me as an end consumer? Consumers generally do not understand things like volatility and that sort of terminology. It is: is this product I am paying premiums into going to deliver the benefits I expect at the point I need it?

Miss A. M. Hutchinson, F.I.A.: You were asked whether there are things that we, as individual actuaries, can do.

I also ask is there a gap in what policyholders expect from the products and what they get.

Is there a place for the IFoA or for other non-company players, perhaps the regulator, to be involved in educating the public more generally rather than it just falling to the responsibility of companies in terms of educating people on what kind of things they should be looking for when they buy products and what questions they should be asking?

Mr Chidley: I will have a go at the second question. I am not an actuary and not quite sure what actuaries can do. If they are going to try to keep it down to two pages, then do not involve a lawyer. They charge even more for abbreviating things than for the long documents.

You suggested that the regulator could get involved in education. I am pretty certain that if I were representing the FCA, which I am not, I would say that I am a principles-based conduct regulator, and that is not part of my remit. It is a legitimate point for them to make.

However, education is critical as set out in the implications section. We believe at some point that the customer has to take responsibility for ensuring the product is understood and suitable and for that to happen education is key.

The consumer panel equally agrees that there is a point when the customer has to get off the fence and make his decision. Already there is a principle to that effect. It is one of the principles of good regulation that customers take responsibility for their decisions.

However, I must also say that the consumer panel takes the view that you cannot expect consumers to be able to do that unless the people providing them with the product have exercised a duty of care towards them in terms of making sure that it is suitable, explaining it properly and so on.

At the moment there is a role that is hard for the financial services industry to get away from. However, broader issues of financial literacy are absolutely crucial. It requires a more significant level of financial literacy to be dealing with more complex products such as life assurance than it does to be thinking about a bank account, a simple loan or whatever else it might be.

That is not a satisfactory answer to your question but my analysis as I see it at the moment.

Mr C. R. Barnard, F.I.A.: (by telephone): Education is key for consumers, but as yet our working party has not focussed on how actuaries specifically can get more involved in this. However, we would generally suggest starting such education at a younger age, perhaps when at school.

I learnt everything at school from Fibonacci numbers to finger painting, but no one ever taught me about bank accounts, pensions or how interest rates worked. I learnt this when I was studying and training to be an actuary.

This is a countrywide issue and should be remediated as early as possible. As actuaries, we have our individual duties to educate people where we can as this relates to our work.

The Chairman: We have not tackled anything about the advice gap. Do we think as a profession that advice is actually affordable all the way down the premium scale?

Do we believe that people who are contributing, say, only £100 a month can afford advice or whether in fact for them it is better to buy simple products with low risk attached to them that they can actually be safely buying without too much thought?

Mr Horwitz: I am far too young to remember the “man from the Pru”, but I have certainly read about him.

The question is: is it time to bring him back? For those who do not remember: the “man from the Pru” would knock-on your door and sell you a policy for a certain amount of pounds a month. This would be an insurance policy or an investment policy, but the important thing is that it was aimed at the mass market.

Some would say that the policies were probably not the best value for money for customers in the world. They probably had a decent margin for the insurance company. But the insurance company was funding this person who was knocking on doors, sitting down and having a cup of tea.

I am going to turn my question on its head and suggest this duty of care for the insurers, for the providers, to reinvent their sales forces along “Man from the Pru” lines. We could suggest to or challenge the regulator and say: perhaps we should find a way to remunerate them for how many products they sell, and perhaps that will close the gap.

The Chairman: I would like to say, too, that my sister, for the first 10 years of her married life, bought everything from the “man from the Pru”: household insurance; motor insurance; life insurance, the lot, because he was a nice guy who came round. If she ever had a claim, he made sure it was paid. As far as she was concerned, that was worth paying a little bit extra for.

Mr P. Fulcher, F.I.A.: Sadly the “man from the Pru” stopped because that particular company worked out that it was actually costing more than the premiums that they were getting in, and there was genuine discussion that took place with customers to say: look, you can have your benefits, we are just not coming to collect the premiums any more.

Interestingly, customers were not valuing it as a service to come and collect premiums, they were valuing it sometimes just for someone to pop round and have a cup of tea, but sometimes, as you say, because they wanted a bit of financial advice.

Mr Horwitz: Here is a really radical idea. Given that we have a serious issue with care in this country and the government are trying to think about what they are going to do for care, perhaps we will combine your insurance collection and care, and all these lonely people will get both.

Mr Spain: The Prudential was one of the biggest players in what was called industrial branch assurance, where people went round collecting an old penny a week or even – tuppence a week – in old pennies. The premiums could not be collected less often than every 2 months.

From the proceeds of all of that, the Pru made profits to build this beautiful building. The Pearl up the road is now a hotel. It had the most beautiful marble staircase paid for from policies which cost a penny a week. The profit margins must have been pretty good.

I have never seen the Britannic Building in Birmingham, but I imagine it is something similar.

There was a lot of money in that. It is not there anymore.

May I just go back to flexibilities? Think about a 10-year policy. It costs, if things do not work out. What is going to happen after, say, 5 years, on average, is going to be quite different from what happens after 10 years or 15 years. Path dependence is really important. The punter has to have it explained: remember surrender value penalties? You promised to pay us for 15 years and you have not done so and therefore we are going to give you a lot less than you paid in. That was the reality.

Flexibilities cannot be built in unless they are going to be paid for in advance, which is going to reduce the amount available for longer-term investment.

Actuaries should be explaining this to clients, whether it is their employers, their sales force or their customers at the end. Flexibilities sound great but not really deliverable in terms of reasonable policyholders’ expectations.

Miss Hussain: There is a distinction between thinking of flexibility in terms of customers’ needs and flexibility as a guarantee. Where we were coming from as a working party was that in 5 years’ time I have no idea what my life is going to look like, and so my needs will be very different.

We can either attempt to produce really short-term products, say 5 years with mandatory reviews, or we can maybe go to the other extreme and come up with something more generic, perhaps, unit-linked products, and you change your benefits according to your needs at that time.

So there are things that we can do in the industry without impacting profitability and without tying ourselves in as a company. We just need to think bigger.

We are moving into a new generation of consumers, those who want information instantly. They want to be able to do whatever they want at any time they want, and we need to be flexible if we are to cope with future demands.

It is not just about guarantees and being able to think of every scenario, it is about offering a product where we can give the customer the right thing at the right time.

Mr J. Parmar, F.I.A.: I want to pick up on other comments. Insurance, life insurance, long-term products, they are incredibly complex and various. The original contribution referred to “insure tech”, and certainly there is an appetite to invest here.

Where this is starting is typically business that is very simple to transact. It is something that you can do on your mobile phone in a matter of seconds. In this instance, ease-of-use is great and cover is great, but value for money probably is not and the consumer is not really bothered about that. So is that an issue?

What we as a profession are very good at is the numbers and the technical analysis. What we tend not to think about are the emotional aspects of decision-making. So tying this into the question about how you measure customer service, customer experience is what you feel emotionally in a transaction or a purchase and how well you thought that went.

If I am buying a car and somebody is being very complimentary to me they may well sell me a car which costs a lot more than I want to spend but that good feeling will make me think that actually that was a good sales process.

In an insurance situation, it may be that when I purchase a mortgage, an adviser may say: “… a very real risk is if you are made redundant you may well have your policy invalidated through not being able to pay your premiums. My advice would be to take out a rider for redundancy cover”.

To me that may well sound fantastic at the time and I will give great feedback. A few years down the line, when that situation occurs and I find that actually the terms and conditions show that for me that was not appropriate, it is a little bit too late to go back and revise that customer feedback.

Coming back to an earlier contribution, trust is essential. With reference to the “man from the Pru”, I worked in the Indian reinsurance sector for a number of years. By far the biggest life insurance company was the state monopoly, although it is very much a private insurance market now. It has a vast sales force. You are talking about millions of people. Very much of this is trust-based selling. The person selling is quite typically somebody in your family. It is a part-time thing that they do.

It is all about knowing who that person is and being able to trust them.

If there is a question, I would ask “What extent do you consider the emotional aspects of transacting, and just how difficult does that make measuring and changing things for the better”?

The Chairman: This is normally summed up in behavioural economics and the fact that people do not want to admit that they made a mistake when they buy something.

I am now going to introduce the closer, Paul Fulcher, from Nomura. He is the head of Asset Liability Management (ALM) Restructuring for Nomura International Plc. He is responsible for delivering Solvency II ALM and the capital market solutions to insurers across Europe.

In his professional capacity, he chairs the Life Research Committee and he is also a member of the Life Board.

Mr Fulcher (closing the discussion): As Chair of the Life Research Committee, we commissioned this working party 3 years ago, and they took on a very large task.

There were many very difficult questions for them and they have not come up with all the answers. It is ongoing work. They have certainly posed some important questions and made some very good suggestions for things to take forward.

The profession has other working parties looking at consumer areas. As a profession, we are not always as joined up enough in our research as we should be. It probably should not be news to the presenters that both of those working parties exist.

To highlight the work that the profession is doing, we have one working party looking at the impact of the low-rate environment and Solvency II, and the ability of product providers to offer guarantees at a cost that customers will pay.

We have another group looking at consumers and their understanding and experience of with-profits. We should not think entirely of the new products we are selling to new customers. We have legacy customers with legacy products.

We have a putative group looking at financial literacy which was a topic that came up a couple of times in the discussion and is mentioned in paragraph 6.2 of the paper.

Perhaps most pertinently is the Consumer Risks Metrics Working Party, which is about to launch a survey of customers via an external survey firm.

They are trying to understand how customers measure risk. What metrics or what risks do customers think of as the risk of their product when they buy it? It might not be reduction in yield. It might not be value for money. It might be something else altogether. Does it pay out when they need it? How flexible is it? We are trying to get some understanding of what those are and then how, given some of the early discussion, you can translate that into metrics that we can communicate to people.

This is a big area of focus for the profession. I encourage everyone in this room to carry on joining in the debates, coming to meetings, sessional meetings and feeding into the research that is being done.

Turning to the discussion, I found it very salutary and a little bit depressing that the paper points out that almost exactly 20 years ago, Jeremy Goford, who was an actuary ahead of his time, was making a lot of the same points about needs-based selling that we are still talking about trying to achieve 20 years later.

It is salutary in the sense it shows that these things are not always that easy. To give an example, which again came up a little bit in the discussion, we talked about product flexibility and maybe the ability to add riders on to products.

In terms of things like value for money, my experience in, say, the Asian insurance market, is that it is often those riders that are added to products that are probably the least value for money, at least in terms of what the customer pays for the rider versus what it really costs to provide it.

And arguably, PPI was a rider, as Mr Parmar said earlier. That is not to say that riders is not the way to go but again it is a complex topic and we need to move forward cautiously.

There were some noteworthy points. There was an interesting discussion about whether the consumer or the provider should be the one who bears the burden of any ongoing review as well as the point that they are probably the least two qualified people to do it. Maybe there is a need for an independent ongoing review process.

There was an interesting debate about the role of competition. Does “insure tech” help? Is competition the solution? Mr Hicks said that it is not a panacea.

There were also some interesting debates about risk metrics, which again feed into the research that is being done. Two or three people in the room said that the worst case did not sound like a great risk metric. It might put people off. It might turn out that it may be the famous last words saying “that was the worst-case scenario” because the chances are it will not be.

But then what is the way of measuring risk? Someone made an interesting point at the end that value for money might not actually be that important to consumers compared to other metrics.

The need for consumer research came up, and again that is something that the Life Board will need to consider whether we want to fund. We are already commissioning two pieces of research on the with-profits side and the risk metric side.

Then one area where the working party was expecting more discussion is duty of care. It is what they thought was one of the more controversial risk topics that was raised. It did not really come up that much in the debate. David Keeler made a very good point that just imposing a duty of care on people is not sufficient. We need to put the customer at the heart of what they do rather than just doing it because they are told to do so by someone. But, to be fair to Mark and the Financial Services Consumer Panel, that is pretty much exactly what they do mean: they do not see duty of care as being a way of people being able to sue people and a box ticking exercise. It is around a change of culture.

I hope we will have a “duty of care” fuller debate going forward.

The Chairman: It remains for me to express my own thanks, and I am sure the thanks of all of us, to the authors, the opener and closer, and all those who participated in this discussion.