The Zhou conquest of Shang (mid-eleventh century b.c.e.) is one of the most frequented lieux de mémoire (sites of memory) of the Chinese tradition.Footnote 1 Form the point of view of traditional historiography, the conquest marks the beginning of the Zhou dynasty (1046/1045–256 b.c.e.)—the last and greatest of the “Three Dynasties” (Xia, Shang and Zhou) that ruled the “Under-Heaven” (tian xia 天下) before the foundation of the first centralized empire in 221 b.c.e. The memory of the conquest and the first Zhou kings became central to the early literary texts whose final versions are known today as parts of the Shi jing 詩經 (The Classic of Poetry, or Poetry) and the Shang shu 尚書 (Exalted Documents, or Documents) Classics. Transmitted texts and excavated manuscripts alike reflect that during the Eastern Zhou period (770–third century b.c.e.), the ruling and intellectual elites of various early Chinese polities widely shared this memory. Upon the canonization of the Classics during the Han Empire (202 b.c.e.–220 c.e.), this memory became one of the foundations of the imperial narrative of the past for many centuries to come. But how was this memory transmitted during the first centuries of the Zhou dynasty, before the Classics had been produced and spread widely? Coming to terms with this question is important both for tracing the early roots of the early Chinese historiographic tradition and for understanding memory production as a process of constant negotiations and adaptations to the present needs of a given society.

The earliest mentions of the conquest of Shang and/or the first Zhou kings can be found in inscriptions on excavated bronze vessels and bells. Chinese Bronze Age elites used such objects for feasts and ancestral sacrifices, as dowry or wedding presents, and as burial goods. Focusing on the inscriptions from around the mid-eleventh to the early eighth century b.c.e., defined in current historiography as the Western Zhou period, I address the following questions to these texts:

• How was the conquest commemorated by its eyewitnesses?

• When did the commemoration of the conquest and the first kings become a part of an intentional memory policy?

• Who cultivated this memory?

• What present situations involved the acts of evoking the past?

• Which changes in the Zhou foundational narrative occurred during the period under consideration?

In the following, I demonstrate that a stable narrative emphasizing Kings Wen 文 and Wu 武 as a pair of founding fathers of the Zhou was established by the mid-tenth century b.c.e. at the cost of downplaying the role of King Cheng 成, despite the fact that the conquest of Shang was accomplished during his reign. I argue that the reason for focusing on Kings Wen and Wu and downplaying King Cheng's role was in the Zhou kinship cum political organization, in which commemoration of the earliest common progenitors served as a basis of corporate integrity in a network of patrilineally related lineages. I show that the royal house cultivated the memory of the first kings using various media, including rituals, utensils, royal speeches, and inscriptions, and that this memory was usually reactivated in the context of political negotiations, and was by no means part of routine, bureaucratic discourse. I show examples of the ways this memory was transmitted within metropolitan lineages and how it was modified according to the current needs of the royal house and other aristocratic families.

The Conquest of Shang and the Western Zhou Chronology

The conquest was a gradual process rather than a single event. According to transmitted tradition, King Wen (“Adorned”) received the Heavenly Mandate to overturn the decadent Shang dynasty, but he died before being able to achieve his goal.Footnote 2 His son King Wu (“Martial”) conquered Shang four years later for the first time. He installed there a surviving Shang prince as a nominal ruler under supervision of his three brothers. After King Wu's death four years after the conquest, the puppet Shang ruler and the three treacherous supervisors raised a rebellion. It was suppressed during the reign of the second king, Cheng (“Accomplished”), wherein another brother of King Wu, Zhou gong 周公 (usually translated as “Duke,” but more accurately rendered as “Patriarch”) Dan 旦, played the leading role. This time Shang was re-conquered and destroyed. This was the second and the final conquest of Shang.Footnote 3 The conquest then extended further to the east, reaching the territories of the former Shang allies in western Shandong 山東 and leading to the foundation of Lu 魯.Footnote 4

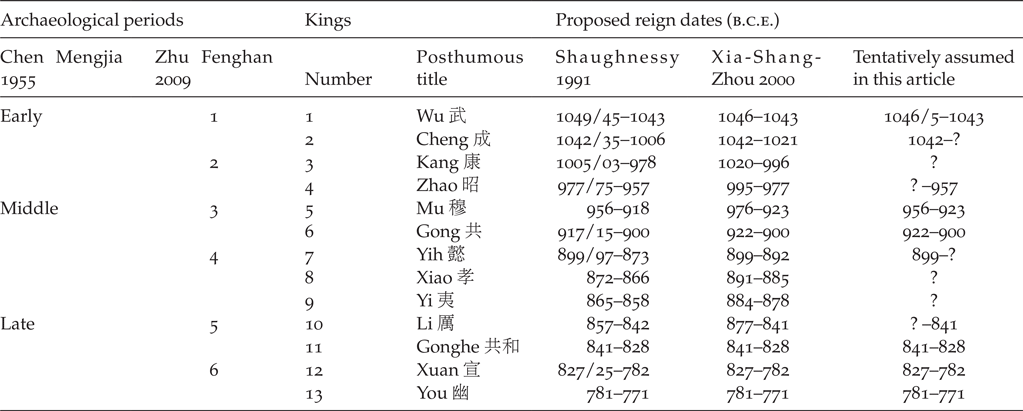

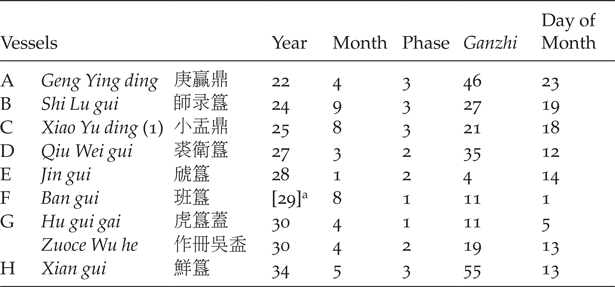

As the Zhou conquest of Shang marks the beginning of the Zhou dynasty, from a modern perspective, it is essential to know its date. However, people cared less about dates at the time of the conquest, as it was sufficient to remember what happened and where it took place. Hence, records of exact dates of events seldom appear in early inscriptions.Footnote 5 Although events dating becomes common at the end of the reign of King Mu 穆 (the 5th king) and during the reign of King Gong 共 (the 6th king), it declines during the reigns that followed, only to gain popularity again during the second half of the ninth century b.c.e.Footnote 6 It is not before 841 b.c.e. that the chronology of Zhou kings’ reigns is clearly established.Footnote 7 Based on various references in Warring States period texts and divergent assumptions about the Zhou calendar, scholars have proposed around thirty different dates for the conquest.Footnote 8 Currently, two dates, 1045 b.c.e. or 1046 b.c.e., have become widely used, but neither of these is secure.Footnote 9 The dates of individual reigns are equally controversial (see Table 1).Footnote 10 Therefore, in the following discussion I will provide exact dates only for the kings whose chronologies can be plausibly reconstructed, but I will also use sequential numbers for these whose dates are still uncertain.

TABLE 1 Variants of Zhou periodization and chronology

Table 1 further shows the conventional subdivision of the Western Zhou period into three subperiods of four or five reigns. This scheme, developed by archaeologists and later adopted by historians, is arbitrary and crude, because it lumps together changes in material culture and historical phenomena that ought to be considered separately. Many archaeologists and bronze specialists use a six-part periodization, subdividing each of the periods in two parts.Footnote 11 This sometimes enables us to establish a finer chronology of bronze vessels and bells and their inscriptions. It is now the turn of historians, who use inscriptions as sources, to develop a more chronologically informed approach to the Western Zhou social processes and changes.Footnote 12 In my discussion, I will pay a considerable attention to the issue of various bronzes’ dating, including revisions of the dates of several important inscriptions in the Appendix.

Bronze Inscriptions and Western Zhou Social Memory

During the twentieth century, bronze inscriptions became recognized as important sources for the study of the social and political history of the Western Zhou period.Footnote 13 Although some inscriptions may contain historically relevant information, inscribed bronzes have been more broadly understood as media of religious communication between the living and the ancestors to whom they were often dedicated.Footnote 14 However, often enough, bronze objects were equally explicitly dedicated to the living, as well as to posterity. Hence, Wang Ming-ke has proposed interpreting their functions in Zhou society in light of the theory of social memory.Footnote 15

In the 1920s, Maurice Halbwachs demonstrated that human memory functions within a collective framework. Individual memories are shaped through communication within a group that collectively produces its representations of a common past. As memory is always selective, different groups of people—families, social classes, or religious groups—produce different collective memories, which in turn give rise to different social identities and different modes of behavior. Since humans’ sense of reality is inseparable from present life, the image of the past within a social group is shaped by its current needs. The agents who manage the memory can use it to pursue their goals, which can be of political nature.Footnote 16 Eric Hobsbawm further showed that societies “invent traditions” responding to political changes, while Benedict Anderson discussed how modern nations are being constructed as “imagined communities” within the political boundaries of national states. Therein, deliberate strategies of both remembering and forgetting serve to maintain the common national identity.Footnote 17 Based on this theoretical background, Wang Ming-ke has suggested looking at inscribed bronzes as “containers of social memories.”Footnote 18

Attempting to reveal what kind of identities and what social organization inscribed memories might support, Wang identifies “the ancestors’ contribution to the Zhou conquest of Shang” as one important theme. Pointing out that most inscriptions referring to it derive from the Zhou metropolitan region in the Wei 渭 River valley in Shaanxi 陝西, he supposes that the group that shared such memories consisted of members of old polities of this region that had their roots in pre-dynastic Zhou time and had been Zhou allies in the conquest campaign. Cultivating matrimonial relationships between the old families, retelling the story of the conquest in ceremonies by current kings, and inscribing the conquest's memories on bronze vessels supported the in-group feeling in their “confederacy.” Wang supposes that other families, whose ancestors did not participate in the conquest, commemorated it too as they were “willing to remember some crucial events that tied [them] more closely to the Zhou royal family and the allies in the Zhou conquest.”Footnote 19

In the next step, Wang moves towards transmitted literature from the Warring States to the Han period. He exemplifies that some memories of the Western Zhou period had been altered, while many facts had been forgotten. He identifies this as reflections of “cultural amnesia” and, predictably, suggests that the latter had been caused by the relocation of the Zhou court in 771 b.c.e. The latter event both caused the loss of material memory carriers (bronze vessels), and triggered political processes that generated new social needs, which, according to Halbwachs and Hobsbawm, required new images of the past. The authors of the later periods reinvented their distant past, as this was better suited to their aim of constructing their huaxia 華夏 cultural and political identity.Footnote 20

Wang makes an important contribution inasmuch he recognizes the agency of lineages in social and political processes—from the conquest itself up to the collective production of the conquest's memory. Wang's study fosters an interactive understanding of the Zhou society and fits the current trend of viewing archaic polities as stages of “collective action” involving various forms of top-down and bottom-up transactions and negotiations.Footnote 21 However, looking at the whole Western Zhou period as a single block of cultural reality while comparing it to the opposite end of the long Zhou epoch, Wang misses an opportunity to reveal changes, including the reshaping and selective forgetting of earlier narratives, that occurred in the memory culture of the metropolitan elites already during the mid-eleventh to early eighth century b.c.e.

Just a few years after the publication of Wang's pioneering, but, unfortunately, not widely known study, an archaeological sensation provided a new opportunity to ponder the process of memory formation in Western Zhou society and the functions of bronze inscriptions in this process. A hoard of twenty-seven bronze vessels was discovered in Yangjiacun 楊家村 in Meixian 眉縣 county, just south of the ancient Zhou Plain, which was the main ritual, political, and administrative center of the Western Zhou kings.Footnote 22 Most of the vessels were commissioned by a member of the Shan 單 lineage whose personal name was transcribed into modern characters either as Lai 逨 or Qiu 逑 (the latter transcription will be followed in this study).Footnote 23 The ding cauldrons were dated to the forty-second and forty-third years of King Xuan's reign (786 and 785 b.c.e.). A 372-character-long inscription on a pan basin recorded the commissioner's pedigree from the time of the conquest of Shang interlinked with the line of the Zhou royal house that all Qiu's ancestors mentioned in the inscription faithfully served.Footnote 24 The Qiu pan became immediately famous for being the first material proof of the Zhou kings’ list recorded in the “Zhou ben ji” 周本紀 chapter of Sima Qian 司馬遷's (145–90 b.c.e.) Shi ji 史記. At the same time, the Qiu pan corroborated the observation based on a similar but earlier record of pedigree aligned with the history of the royal house, the Shi Qiang pan 史牆盤, dating around 900 b.c.e. and excavated in 1976, that the Western Zhou official historical narrative only slightly differed from the transmitted history.Footnote 25 In any case, both pan and some other inscriptions could be now treated as evidence of a high historical consciousness within the Western Zhou nobility, which, in turn, could be examined from a socio-anthropological perspective. For instance, Lothar von Falkenhausen has diagnosed “the strategic importance of talking about the past as one way of furthering particular lineage interests vis-a-vis the royal government in a highly public context.”Footnote 26 Considering a discrepancy between the representation of the history of the Shan lineage recorded in the Qiu pan and the data about this lineage in much later—Tang (618–906)—transmitted sources, as well as pointing out some irregularities in the list of Qiu's ancestors, Falkenhausen has supposed “that the author, or authors, of the Qiu-pan inscription manipulated historical memory.” Matsui Yoshinori went even so far as to define the Qiu pan (or, in his transcription, the Lai pan) as tsukura reta rekishi 作られた歴史 (“made up history,” or “invented history”) “designed to underscore the achievements of the family, and created with Lai's power as the backdrop.” Matsui suggests that:

the royal genealogy inserted into the inscription of the “Lai pan” was an important tool, providing a sense of reality to such an “invented history,” and acting as a validating site in the “collective memory” of the dynastic foundation.Footnote 27

Although the English version of Matsui's article repeatedly speaks about “collective memory,” making the reader anticipate some socio-anthropological insights, it does not specify what this “collective” actually is. The Japanese original only mentions “Shū hito-tachi ni kioku” 周人たちに記憶 (Zhou people's memory).Footnote 28 Neither version, as is indeed the case for hundreds of other papers working with the concept of “Zhou people/people of Zhou,” attempts to define it as a socio-political entity. Still, it is possible to deduce that when Matsui speaks of ke 家 / “families,” he means aristocratic lineages, and he regards these as active participants in the memory-production process. Although Falkenhausen does not thematize “collective” or “social” memory in his works, his views are quite close to these of Wang Ming-ke and Matsui, as he assumes that aristocratic lineages kept their own archives and engaged themselves in reconstructing their own history.Footnote 29

In a recent contribution to a volume on historical consciousness in the ancient world, I attempted to provide both a sociologically and chronologically sensitive view of the Zhou collective memory formation, comparing bronze inscriptions from the Western and Eastern Zhou periods that refer to the conquest of Shang and the first Zhou kings. I pointed out that during the Western Zhou, such inscriptions were usually commissioned by people who—like Qiu/Lai—belonged to metropolitan Ji 姬-surnamed lineages related to the royal house by patrilineal kinship. A few lineage outsiders, who equally evoked these memories, were close associates or important political partners of the current kings, while some of them were also affiliated with the Ji clan by affinal ties.Footnote 30 Commemorations of the conquest and the first kings were usually embedded in royal speeches addressed at the vessel's commissioner. Considering that metropolitan elites would be unlikely to invent royal speeches—not necessarily because of the possible court censorship, but because of mutual control within the elite—I suggest that the right to reproduce such speech with an allusion to the memory of the Zhou foundational past signified a high distinction of specific addressees and emphasized their close relationship with the royal house. Thus, in contrast to Wang Ming-ke's assumption that old aristocratic lineages deliberately commemorated the conquest and the first kings to preserve their membership in the Zhou “confederacy,” or to Matsui's hypothesis that insignificant families that accidentally rose to nobility and power invented family histories linking them to the dynasty's founding heroes, I suggest that these inscriptions reflect a targeted memory policy of the royal house. This policy aimed to approximate certain members of the elite and to maintain hierarchy within a network of agnatically and affinally related elite families, instead of attempting to forge a broadly accessible collective memory for a “Zhou nation.” I further point out that Western Zhou inscriptions referring to the deep past reflect genealogical rather than historical consciousness and demonstrate that inscriptions from the Spring and Autumn period equally reflect the transmission of the Zhou foundational memory along genealogical lines.Footnote 31

Regarding the social functions of the memory of the distant Zhou past in bronze inscriptions, neither Wang nor myself have discussed in detail the specific content of commemorative references, nor have we analyzed the means (apart from the inscriptions themselves) by which this memory was constructed. Falkenhausen and other authors focusing specifically on the Qiu pan or Shi Qiang pan have compared these with transmitted history. Matsui, moreover, has attempted to check whether the memory of the royal line underwent changes during the Western Zhou period. As a result, he has primarily revealed differences from the Eastern Zhou and later transmitted texts. The present article will attempt to reveal whether there was a single narrative of the dynasty's beginning from its inception, whether different narratives coexisted, or whether there was a master narrative that changed over time. It will pay attention to the context of commemorative practices as well as to the aspects of mediality, such as the interplay of oral and written communication, and the use of images in the memory transmission. To meet these goals, I will make use of some analytic tools developed by Jan and Aleida Assmann in the framework of their theory of cultural memory.

Western Zhou Cultural Memory and Bronze Inscriptions

Jan and Aleida Assmann's theory of cultural memory relies on Halbwachs’ theory of collective memory, stressing the qualitative difference between two “memory frameworks”: “communicative memory” versus “cultural memory.” Communicative memory is “biographical” and “factual.” It is located within the generation that experienced certain historical events as adults and was able to transmit the memory of these events to descendants. This primarily happens through everyday interaction and storytelling, though it also occurs using different other media such as writing or images. The main social framework through which communicative memory is transmitted is usually the family, although this can also be a neighborhood, a professional group, or other network. While eyewitnesses rely on their own remembering, and storytellers and listeners may change roles, the content and the interpretations of events within the communicative framework may vary and change over time. The horizon of the communicative memory may extend up to three or four generations, or eighty to a hundred years into the past.Footnote 32 It is not tied to fixed events, and it continuously shifts as elder generations pass away and the memories of younger generations come to the foreground.Footnote 33

At the core of cultural memory are the events of the distant past, regarded as foundational for the community. The temporal horizon of cultural memory, tied to these events, does not shift over time. Maintaining the foundational memory serves to stabilize and convey the community's self-image, and to facilitate the concretion of identity, by which social groups distinguish “us” from “them.” Cultural memory, maintained through figures of memory, always depends upon a specialized practice of cultivation, including cultural formation (texts, rites, monuments) and institutional communication (recitation, observance). Here, we can see that Jan Assmann's figures of memory are similar to Nora's lieux de mémoire.Footnote 34 The production of stable figures of memory can take place long before the invention of writing. Thus, “the distinction between communicative memory and cultural memory is not identical with the distinction between oral and written language.” The cultivation of the cultural memory involves organization, including the “institutional buttressing of communication,” e.g., through formalization of the communicative situation in ceremony and the specialization of the bearers of memory (priests, archivists). However, although cultural memory “is fixed in immovable figures of memory and stores of knowledge,” it always reconstructs the past in relation to the present situation. Thus, the “every contemporary context relates to these [figures of memory] differently, sometimes by appropriation, sometimes by criticism, sometimes by preservation or by transformation.”Footnote 35

Martin Kern has employed the theory of cultural memory for his analysis of religious practices and representations reflected in the Classics. He identifies the ritual songs in the Shi jing and the speeches attributed to early kings in the Shang shu as expressions through which the foundational past was imagined and commemorated by later generations, especially in the context of ancestral sacrifice, which was as much a religious as a political institution of the Zhou elite. In the same work, Kern addresses bronze inscriptions, treating them as a background against which the received literature can be studied. For instance, he expects that comparisons with inscriptions may reveal when certain elements of the foundational narrative have been established and, accordingly, when the related parts of the Shang shu and Shi jing came into being. Drawing on recent phonological and lexicological studies, he undertakes a quantitative evaluation of the use of some key concepts (such as the “Heavenly Mandate” or “Son of Heaven”) in inscriptions, chronologically attributed to the early, middle, and late Western Zhou periods. He observes that the commemoration of the king-founders Wen and Wu and the claim that they had received their right to rule directly from Heaven “take on particular urgency only toward the end of the Western Zhou, some 200 years after the death of King Wu.” Kern suggests that the production of an “increasingly coherent and solidified imagination of the beginnings of the dynasty and its original legitimacy” might have been a “response to the gradual political and military decline of the dynasty over its last century,” by which he means the ninth to early eighth century b.c.e. Pointing at disparities between the language of the inscriptions and that of the Classics, he concludes that even the core parts of the Classics, traditionally regarded as originating from the very beginning of the Zhou dynasty, were either partially updated, or entirely created during the late Western Zhou or early Eastern Zhou period.Footnote 36

Kern's work supports, though slightly modifies, the observations previously made by Vassili Kryukov and Kai Vogelsang, who equally compared selected Shang shu and Shi jing texts with bronze inscriptions, aiming to reveal their chronological correlations.Footnote 37 Kryukov proposed that the earliest parts of the Shang shu derive from the eighth to seventh century b.c.e.,Footnote 38 while Vogelsang suggests shifting the burden of proof on those who claim that they date from the early Western Zhou.Footnote 39 Vogelsang identifies numerous discrepancies between the language of the inscriptions and the Shang shu.Footnote 40 He also mentions that two inscriptions displaying the greatest number of parallels with the royal speeches in the Classics, the Da Yu ding 大盂鼎 (JC2837) and the Mao gong ding 毛公鼎 (JC2841), discovered during the nineteenth century, may be forgeries.Footnote 41 As both of them indeed represent conspicuous examples of inscriptions commemorating the Zhou foundational past, I will briefly dwell on the debate about their authenticity.

Suspicions about both inscribed vessels were raised by Zhang Zhidong 張之洞 (1837–1909).Footnote 42 Zhang doubted that a genuine inscription may share any language with a transmitted text—in this case the “Jiu gao” 酒誥 chapter of the Shang shu. Most of Zhang's arguments against the Da Yu ding cannot be followed, especially after more than a century of documented discoveries of—still not so numerous—bronze inscriptions that share their language and ideas with this inscription.Footnote 43 Indeed, other inscriptions—as Vogelsang and Kern demonstrate—date from the middle and late Western Zhou periods, and Zhang's opinion that such complex content and expressions are unlikely to appear in a very early inscription is reasonable.Footnote 44 As I will demonstrate below, the problem of the Da Yu ding is not that it may be a fake, but that it has been dated too early.Footnote 45 In any case, there were no further attempts to discredit the authenticity of this vessel. However, the Mao gong ding, a mid-to-late ninth century b.c.e. cauldron with the so far lengthiest known inscription of the Western Zhou period (479 characters),Footnote 46 was declared a forgery in an influential publication by Noel Barnard during the mid-1960s.Footnote 47 Among other things, Barnard regarded as suspicious that the Mao gong ding shared some wording with the “Wen hou zhi ming” 衛侯之命 chapter of the Shang shu and with other previously published inscriptions.Footnote 48 Since the early 1970s, several scholars published studies that rehabilitated this vessel and its inscription.Footnote 49 More recent studies considering the materials excavated after mid-1970s dispelled many suspicions expressed by Barnard and provided further evidence against his underlying theory of “characters constancy.”Footnote 50 This is not a suitable place for a detailed review of these studies, but I would just like to recall that Barnard wrote his review in 1965, before the major finds of bronze inscriptions, such as the Zhuangbai or Yangjiacun hoards, were made. Even the He zun 𣄰尊 (JC6014), equally displaying impressive parallels with the wording of the Classics, discussed below in the present article, was not yet published. New discoveries have demonstrated that inscriptions frequently operate with stock phrases, and the use of similar expressions in two inscriptions does not suggest that one of them should be a forgery. On the other hand, many expressions and graphical forms that looked odd and had no counterparts in other inscriptions known by the 1960s have been attested on vessels excavated only later. If such prototypes were not known earlier, how could the artisans of the nineteenth century use them for forging the Mao gong ding?

By defending the Da Yu ding and the Mao gong ding, as well as other “non-standard” objects excavated before the advance of modern archaeology, I do not intend to rule out the problem of forgery in general. This problem was and is addressed by Chinese specialists, who have already sorted out hundreds of (often genuine) objects with fake carved inscriptions that were held in the imperial and private collections until the mid-twentieth century. It was indeed not accidental that many such inscriptions contained some pieces of the foundational narrative, as this increased their market value. I am confident that the inscriptions included into the Yin Zhou jinwen jicheng 殷周金文集成, published during the 1980–1990s by the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences based on the preliminary work by Chen Mengjia 陳夢家, can be safely used. On the other hand, I am concerned about the growth of the black market of bronzes during recent decades. The dispersion of hundreds of looted objects among private collections across China not only leads to the loss of precious archaeological data, but also makes them available as models for new forgeries, which can be produced now with much more expert knowledge than was accessible to artisans from Song to Qing. I thus think that unprovenanced objects from recent private collections should be assessed with great caution, especially when they refer to the Zhou foundational memory. I will address the issues of provenance and reliability of individual bronzes in respective footnotes.

Whereas the quantitative approach clearly demonstrates the exclusive character of inscriptions referring to the Zhou fundamental past, it is all the more astonishing that these very inscriptions are often treated as representative. In a recent work on the politics of the past in Early China, Vincent Leung takes Western Zhou epigraphy as a point of departure for a study that mainly focuses on Eastern Zhou and Western Han literature. Leung explicitly avoids engaging in the debate about memory and attributes all references to the past to the realm of “history,” pointing out that “in the Western Zhou, all history must be family history,” and “the past was essentially delimited to the genealogical field.”Footnote 51 It is not so clear whether he admits that different families had different notions of the past. Comparing three lengthy inscriptions mentioning the conquest and the first kings, which belong to the best-known and most frequently cited Western Zhou texts (including the already mentioned Da Yu ding), Leung defines them as “typical,” and even goes so far to state that “a majority of the inscriptions describe similar official exchanges between the Zhou king and his subject” and that they “almost always begin with the present-day Zhou king recounting the virtues of King Wen, and sometimes those of King Wu.”Footnote 52 In fact, no more than 11 percent of all published Western Zhou inscriptions mention a king, while it is also arguable whether every meeting with the reigning king, regardless of circumstances and purpose, can be understood as an “official exchange.” Only a tiny portion of inscriptions recording any interactions with the king includes references to the first kings, and only half of the inscriptions that mention them do so in connection to the Zhou foundational past. I therefore compiled a list of all (just two dozen) relevant cases, including the information about the dates, the contexts of references and the identity of commissioners (see Table 9 in the Appendix).Footnote 53

Scholars who expect bronze inscriptions to reflect certain “common” Zhou representations, assume that Zhou society was thoroughly standardized. As a result, they regard unique features either as suspicious or as generalizable pars pro toto examples, thus underestimating the complexity of early Chinese social reality and eventually making misleading observations. Inscriptions are not just random “philological entities” delivering pieces of information on various social phenomena.Footnote 54 They are intrinsically related to specific people who belonged to different social groups that could assume different perspectives on both the present and past. Taking into account the identity of inscriptions’ commissioners is necessary to understanding the social setting of various discourses.Footnote 55 Such differentiated readings reveal that even within the Zhou metropolitan society, some groups participated in the discourse about the Zhou foundational past, while others had only limited access to it.Footnote 56 The fact that some key concepts (e.g., the Heavenly Mandate) appear in inscriptions very seldom is most likely because they make part of an exclusive discourse. Nevertheless, like everywhere in the world, the privileged groups who participated in exclusive discourses likely had a greater impact on the formation of the early Chinese cultural memory than these who produced a mass of similarly looking appointment inscriptions that barely mention anything beyond assignments of offices and lists of gifts. Thus, establishing the identity of the vessels’ commissioners, including their lineage affiliation and relationships with the royal house, is relevant both for reconstructing the social composition of the Zhou elite and for understanding how different discourses were embedded in the social structure.

In the following, I will discuss in detail several inscriptions, treating them not as representative, but as outstanding, unique evidence of the process of early Chinese cultural memory production, and trying to reveal who participated in this process.

The Conquest of Shang in Inscriptions of Contemporaries

Inscriptions from the first post-conquest decades are generally similar to inscriptions from the late Shang period.Footnote 57 They are normally very short and consist only of ancestral titles, names, or family signs.Footnote 58 Inscriptions with event notations are extremely rare, and these usually derive from the closest surroundings of the royal house.Footnote 59 They equally only very seldom include direct speech.Footnote 60 Several inscriptions from the reign of King Cheng (the second king, r. 104 b.c.e.2–?) or slightly later mention the conquest of Shang. The most famous of them is the Li gui 利簋 (JC4131), counting 32 characters. It was excavated from a hoard in an insignificant place in the middle part of the Wei valley together with several vessels of a later date. Li participated in King Wu's campaign against the Shang (Wu wang zheng Shang 武王征商), while the king personally rewarded him for his achievements, possibly as a diviner. The Mei situ Yi gui 沬司徒疑簋 (JC4059), counting 24 characters, was excavated from a cemetery of Wei 衛, a Zhou colony established about 120 km from the ruins of the Shang royal center. Its commissioner commemorated that the king (plausibly King Cheng), who “pierced and struck the Shang Settlement” (ci fa Shang yi 朿(刺)伐商邑), appointed Kang shu 康叔 (King Wu's brother) and himself to perform outpost service (bi 鄙) in Wei. The unprovenanced Xiaochen Shan zhi 小臣單觶 (JC6512), counting 21 characters, commemorates that the king (similarly King Cheng) stayed in Cheng shi 成𠂤 (師) (Accomplished Encampment), probably corresponding to Chengzhou 成周 (Accomplished Zhou), after having “conquered Shang” (ke Shang 克商), and that the Zhou gong 周公 awarded the commissioner. The commissioners of these three vessels were contemporaries of, or, at least in one case, participants in the conquest of Shang. They had personal contact with Kings Wu or Cheng, or with King Wu's brothers, Zhou gong and Kang shu. Their memory of the conquest was factual and based on their own experiences. The same is true for most of the early inscriptions that mention temple names of the kings Wen, Wu, and Cheng. Their commissioners commemorated their own interactions with these kings or mentioned ancestral sacrifices that the reigning king performed in the first Kings’ honor thereby serving as a pretext for the royal gift-giving (see Nos. 1–11 in Table 9 in the Appendix).

Early inscriptions referring to the conquest of Shang can be compared to other contemporary inscriptions commemorating donations in connection with military campaigns. For instance, Xiaochen Shan zhi reads:

The King, after having conquered Shang, was in Cheng shi. Zhou gong granted xiaochen (Minor Servant) Shan ten strings of cowries. [Shan] used [this occasion] to make a treasured venerated ritual vessel (Xiaochen Shan zhi, JC6512).

王後𪠦克商, 在成𠂤(師), 周公易(賜)小臣單貝十朋, 用作寶尊彝。

An inscription excavated in 1896 in vicinity of Longkou 龍口 in Shandong province commemorates another campaign:

In the year when gong the Grand Protector fought the insurgent Yi [people], in the eleventh month, day geng-shen (57), the gong was in the Zhou* Encampment, the gong granted Lü ten strings of cowries.Footnote 61 Lü used [this occasion] to make a venerated ritual vessel for his father (Lü ding, JC2728).

唯公大保來伐反尸(夷)年, 在十又一月庚申, 公在盩𠂤(師), 公易(賜)旅貝十朋, 旅用作父尊彝。

Awards and appointments received from the king or other superiors could be relevant for both a person's status during his life and the honors paid to him during his funeral. Because of their impact on the status of persons and their families, donations became a subject of inscriptions already during the late Shang period. Other events were mentioned in inscriptions insofar they served as pretexts for donations and as reference points for the commissioners’ own biographies.Footnote 62 From a larger perspective, memories about donations received by family founders could become foundational for generations of their descendants, so long as they were able to inherit related privileges and to derive from them long-lasting benefits. In this case, events from the deep past could become fixed points in the memory of lineages and could facilitate the concretion of their identities as in-groups. However, such memories would not necessarily be shared between different lineages or contribute to production of a common “Zhou” identity in the lineage network. Different excavation contexts of the inscribed vessels reveal that commissioners and their immediate descendants made different choices regarding the vessels’ potential as containers of social memories. They could opt to display the vessel with an important commemoration in an ancestral temple so as to preserve it for later generations, as this probably happened to the Li gui, or they could bury it in a tomb and make it disappear, as happened to the Mei situ Yi gui.

Independently of the benefits that later generations could gain from keeping commemorative bronzes, it is also clear that the commissioners of the three bronzes considered in this section mentioned the conquest of Shang as an event in their own biographies, and did not emphasize its significance in any particular way as compared to other events that preceded royal donations. Further conquests, such as that over the Yi in Shandong mentioned in the Lü ding, could be more relevant for their contemporaries settling as colonists in this area. With every new success and award, the memory could potentially shift to a new reference point. Such inscriptions therefore cannot be regarded as reflections of the cultural memory of the Zhou dynasty.

The small number of mentions of the conquest in inscriptions commissioned by contemporaries is noteworthy. Possibly, as long as the generation that experienced the conquest was still alive and passed the memories down within the communicative framework of families or of kin-based military units orally, the need to convey these memories to a durable medium was not yet largely recognized. Another reason may be that, during this early time, bronze vessels could be more strictly associated with ancestral worship in which the ancestors could be regarded as further detached from the human world than they would be in periods to come. Hence, worldly affairs would be less likely to be reported to the ancestors. Yet another banal reason could be that most of the contemporary Zhou elites were nearly illiterate.Footnote 63 Hence, they did not expect their ancestors to have the ability to read and did not think about transmitting their memories to their descendants in writing. The royal house and other major Ji-surnamed lineages worshipped Kings Wen, Wu, and, later, Cheng as ancestors.Footnote 64 They probably commemorated the conquest as a part of their ancestors’ biographies but did not make this explicit in their inscriptions.Footnote 65 There also could be other communicative settings in which the members of different families exchanged memories about this common past. However, these practices stay invisible in early Zhou epigraphy.

Commemoration of the Conquest and the First Kings During the Early Post-Conquest Generations

The earliest evidence about handling the memory of the conquest within the cultural, rather than communicative, memory framework can be found in such inscriptions as the Yi hou Ze/Yu gui 宜侯 (夨/虞)簋 (JC4320, 126 characters), the He zun (JC6014, 122 characters), and the Da Yu ding (JC2837, 286 characters).

(夨/虞)簋 (JC4320, 126 characters), the He zun (JC6014, 122 characters), and the Da Yu ding (JC2837, 286 characters).

Characterized by their extraordinary length, complex structure, and eloquent language, these three inscriptions clearly stand out against the mass of short and simple early inscriptions like these discussed in the previous section. I suppose that the inclusion of narrative elements, quotations of direct speech, lengthy lists, and precise date notations into bronze inscriptions, resulting in the considerable increase in their length, reflects substantial changes to the functions of ritual bronzes in comparison to the late Shang and early Zhou reigns. The bronzes were being used not only as “containers of social memories” of families and lineages, but also as durable “documents” testifying about their owners’ status, rights, and obligations in front of the kings and their peers. Complex narrative inscriptions became widespread during the reign of the fourth king, Zhao (“Radiant”).Footnote 66 The trend in this direction emerged already during the reign of the third king, Kang (“Prosperous”), and the following inscription may reflect this development.

The Yi hou Ze/Yu gui Footnote 67

This inscription represents a uniquely detailed record of investiture (not to be confused with an appointment of an official) of a local ruler, hou 侯.Footnote 68 It lists the awards, properties, and subordinates transferred under Yi hou's control by the Zhou king. It includes a reference to kings Wu and Cheng, which most scholars consider to be only relevant for dating, not for insight into its meaning. Several full western translations are available.Footnote 69 For the purpose of the present study, I will focus on the lineage affiliation of its commissioner, which is relevant for understanding the social and political context of the “present situation” that involved reference to the past. Then I will discuss the ritual setting in which the memory of the conquest and the first kings was recalled, and the medium by which it was transmitted.

The inscription ends with a dedication to the commissioner's deceased father, Yu gong 虞公 (“the Patriarch of Yu”). The lineage name Yu 虞 (OCM *ŋwa) plausibly derives from the toponym wu 吳 (OCM *ŋwâ), identifiable with the Wu mountain in the valley of the Qian 汧 River, flowing through the Gansu corridor and pouring into the Wei River near present-day Baoji 寶鷄.Footnote 70 The three characters  , 吳 and 虞 were used in inscriptions interchangeably as common nouns and probably represent graphic variants of one character.Footnote 71 As proper nouns, they were used to distinguish between the stem and branch lineages descending from the common Wu/Yu stock.Footnote 72 During the Western Zhou period, the main area of activities of the Wu/Yu lineages was along the Qian River and in the present-day Fengxiang 鳳翔 county of Shaanxi province about 50–60 km to the west from the Zhou Plain. At a yet undetermined time, Yu founded a dependency of the same name in present-day Pinglu 平陸 county in south-western Shanxi, which became its main seat during the Eastern Zhou period.Footnote 73 The inscription under discussion is related to the foundation of Yu's dependency in a place referred to as Yi

, 吳 and 虞 were used in inscriptions interchangeably as common nouns and probably represent graphic variants of one character.Footnote 71 As proper nouns, they were used to distinguish between the stem and branch lineages descending from the common Wu/Yu stock.Footnote 72 During the Western Zhou period, the main area of activities of the Wu/Yu lineages was along the Qian River and in the present-day Fengxiang 鳳翔 county of Shaanxi province about 50–60 km to the west from the Zhou Plain. At a yet undetermined time, Yu founded a dependency of the same name in present-day Pinglu 平陸 county in south-western Shanxi, which became its main seat during the Eastern Zhou period.Footnote 73 The inscription under discussion is related to the foundation of Yu's dependency in a place referred to as Yi  /宜.Footnote 74

/宜.Footnote 74

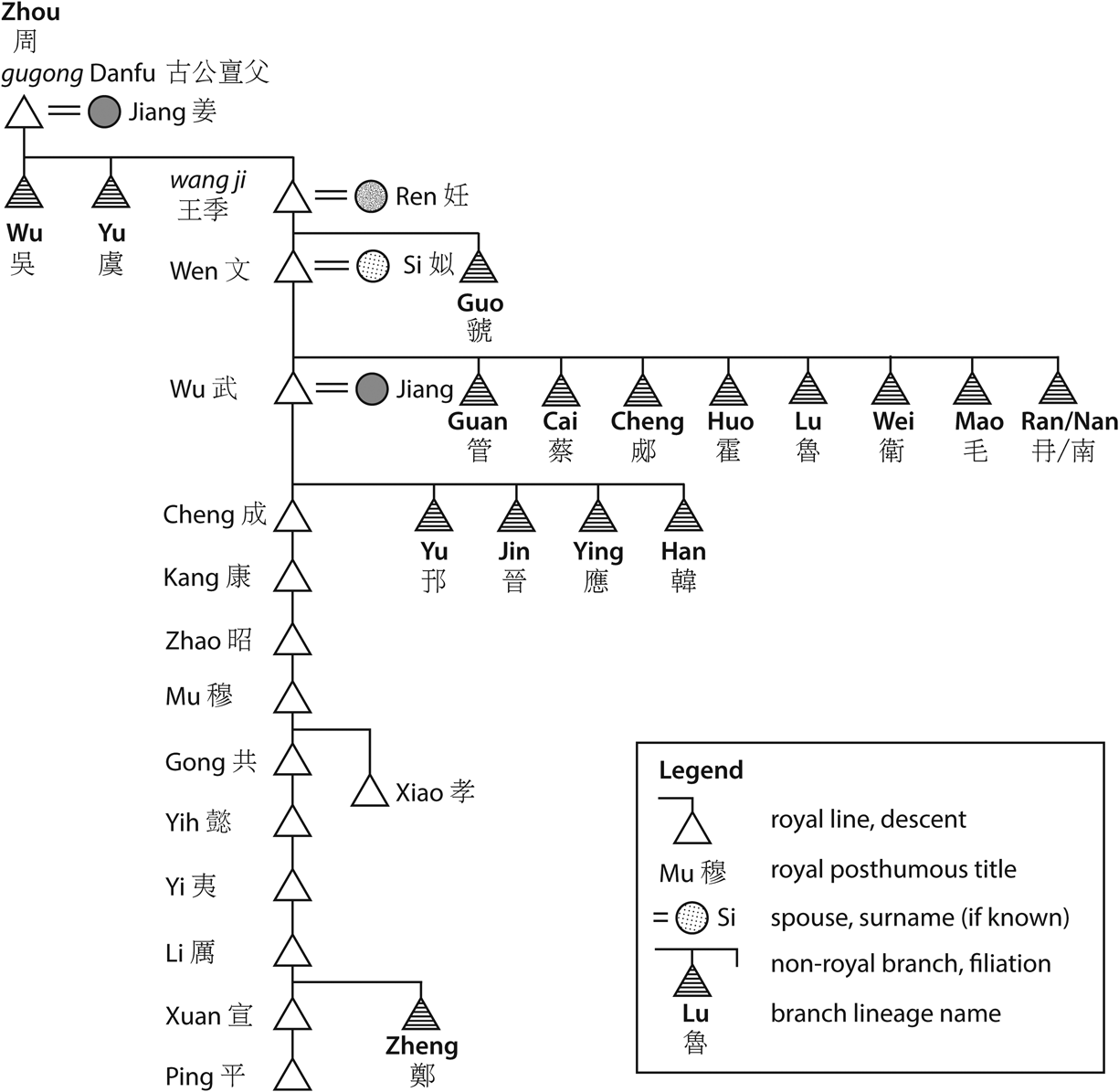

According to the transmitted tradition, the Yu lineage descended from Yu zhong 虞仲, the second-born son of gu gong (“Ancient Patriarch”) Danfu 古公亶父, founder of the Zhou settlement on the Zhou Plain (see Figure 2). Since the Zhou royal lineage descended from the youngest son of Danfu, posthumously venerated as wang ji 王季 (Royal Junior), Yu should have had a senior status in the Zhou lineage network.Footnote 75 If even King Wu's full brothers did not unanimously support the royal house, as already mentioned above, one can imagine that other patrilineal relatives who could claim a higher genealogical status required special care. The ceremony in which the king established his high-ranked kin relative, Yu hou, in a new location should be understood in this political context.

The unique feature of the Yi hou Ze/Yu gui is that it explicitly represents both Kings Wu and Cheng as conquerors. As it will be made clear below, King Cheng would be removed from the official narrative of the conquest later. The memory of the first kings was re-enacted during Yu hou's investiture in the following way:

It was the fourth month. The chen was in day ding-wei (44).Footnote 76 The king inspected the chart of the Shang conquered by King Wu and King Cheng, and then proceeded to inspect the chart of the Eastern Region. The king divined in Yi,Footnote 77 entered the earthen structure,Footnote 78 [and] faced south. The king commanded to Ze/Yu, the hou of Yu, saying: “Relocate to perform border service (or “be hou”) in Yi!” (Yi hou Ze/Yu gui, JC4320)

唯四月, 辰才在丁未, 王省珷王、成王伐商圖, 𢓊省東或(域)圖, 王

(卜)于宜, 宀 (入? 宗?)土南鄉。王令虞侯

(卜)于宜, 宀 (入? 宗?)土南鄉。王令虞侯 曰:𨝍(遷)侯于宜!

曰:𨝍(遷)侯于宜!

The meaning of tu 圖 “drawing, picture, map” in this context has been a matter of debate. Many authors understand it simply as “map.”Footnote 79 A reader can imagine that the king rolled out a map on silk, for example, to pinpoint a location—somewhere in the east—where the new appointee had to relocate. However, considering the history of the evolution of graphical devices for representing terrestrial space in early China, it is unlikely that topographic maps of large geographic areas already existed during ca. eleventh and tenth centuries b.c.e.Footnote 80 More plausibly, tu represented a cardinally oriented, ideologically charged cosmograph, spatially arranging symbols or place names, typologically similar to later divination charts.Footnote 81 Tu charts representing the results of divination are mentioned in the Shang shu. In the “Luo gao” 洛誥, commemorating the foundation of the Luo Settlement (Chengzhou), the Zhou gong sends a messenger to the king who “comes to submit the results of this divination by means of a chart” (ping lai yi tu ji xian bu 伻來以圖及獻卜).Footnote 82 In the Yi hou Ze/Yu gui, the king performed a divination after having inspected the tu of the conquest of Shang and the tu of the Eastern Region.

It is unclear whether tu were only graphical devices, or if they combined graphic and text. It is also unclear what material they were made of.Footnote 83 In any case, in one or another way, the tu represented the achievements of Kings Wu and Cheng in the east. How was this related with the fact that Yi hou was commanded to become the ruler of Yi?

The location of Yi is thus relevant for understanding the context of the reference to the conquest and the first kings. The Yi hou Ze/Yu gui was found in 1954 in Yandunshan 煙墩山 in Dantu 丹徒 county of Jiangsu 江蘇 province, on the southern bank of Yangzi, about 100 km to the east of present-day Nanjing.Footnote 84 Some scholars thought that Yi corresponds to the place of the vessel's discovery.Footnote 85 However, the vessel was found together with eleven other bronzes dating from the early Western Zhou period to early Spring and Autumn period. Considering the heterogenous composition of this group, and the thin evidence of early Zhou presence in this area, it is more likely that the Yi hou Ze/Yu gui was brought there much later as an heirloom.Footnote 86 Huang Shengzhang has proposed a localization of Yi near Yiyang 宜陽 in present-day Henan Province, about 25 km to the west from the eastern Zhou capital Luoyang in the Luo river valley.Footnote 87 Although this localization can be accepted as an option, I suspect that Yi could be located even further in the west. An unprovenanced inscription witnesses that a polity of such a name existed during the late Shang period, while its ruler Yi zi

/宜子 acted as an intermediary between the Shang king and western polities (xi fang 西方).Footnote 88 At the same time, Yi was never mentioned in Shang oracle bone inscriptions (OBI). This means that Yi was not a stable partner of Shang. Probably, it was located far in the western periphery of the Shang interaction sphere, while the latter inscription on a relatively crudely cast tripod witnesses a one-time transaction. Transmitted texts further indicate that the pre-conquest Yi belonged to the circle of polities allied with the Zhou on the eve of the conquest of Shang.Footnote 89 This also supports that Yi was located west of Shang and not very far from the Zhou core territories.

/宜子 acted as an intermediary between the Shang king and western polities (xi fang 西方).Footnote 88 At the same time, Yi was never mentioned in Shang oracle bone inscriptions (OBI). This means that Yi was not a stable partner of Shang. Probably, it was located far in the western periphery of the Shang interaction sphere, while the latter inscription on a relatively crudely cast tripod witnesses a one-time transaction. Transmitted texts further indicate that the pre-conquest Yi belonged to the circle of polities allied with the Zhou on the eve of the conquest of Shang.Footnote 89 This also supports that Yi was located west of Shang and not very far from the Zhou core territories.

Both localizations suggest that the new place of Yi hou's residence was neither in the vicinity of Shang, nor in the Eastern Region. Thus, there was no direct pragmatic relation between the activities of the king-conquerors Wu and Cheng in the east and Yi hou's relocation. In this case, the current king reactivated the memory of the conquest on the symbolic level, reminding contemporaries about past achievements that would serve as the foundation of future stability. In this respect, the Yi hou Ze/Yu gui is similar to inscriptions from later reigns that refer to the memory of the first kings in a general way as part of the foundational past. The act of investiture, by which a certain territory was entrusted to a royal patrilineal relative, served to reproduce the political order established as a result of the conquest. This was one type of “present situation” that involved instrumentalization of a foundational memory, and it was clearly of a political nature. The inscription further relays that during the early post-conquest generations, apart from oral communication, the memory of the conquest and of the first kings was transmitted with the help of material objects, including visual representations and ritual utensils. Once this ritual commemoration was recorded in an inscription, this new instrument was added to the toolkit of memory-keeping, and the archaeological context of the vessel's discovery suggests that it was used other the course of many generations.

The He zun

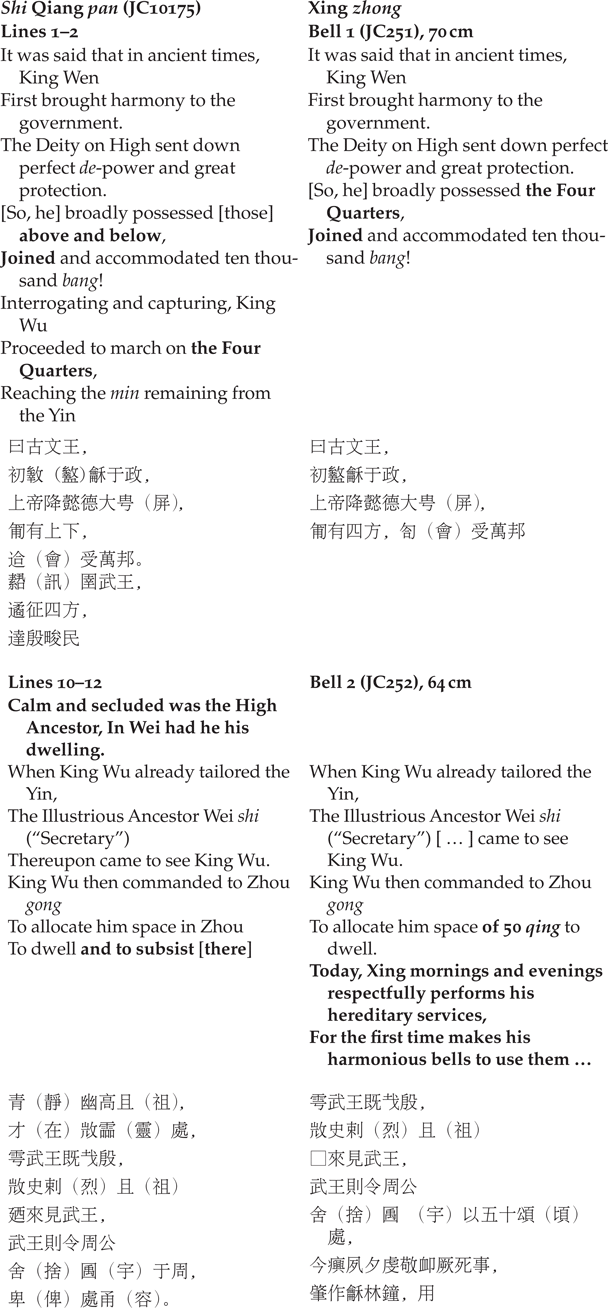

The He zun provides a more detailed account of a different ceremony that also involved the commemoration of the conquest of Shang and the first kings. It quotes several royal speeches encased in one another. My analysis below will focus on three aspects: the identity of the commissioner, the purpose of the reflected interaction, and the speech as a medium of memory transmission. Although several translations exist, there are discrepancies in readings of some key terms.Footnote 90 Hence, I will include a full translation below:

The King moved [his] residence to Chengzhou for the first time. [He] returned [to the west in order] to carry out the feng ritual for King Wu.Footnote 91 [He performed] libation sacrifices starting from Heaven's [shrine]. In the fourth month, day bing-xu (43), the king made an announcement to the minor sons of the ancestral shrine in the Lofty Chamber. [He] said: “Formerly, your pious patriarchs were able to approach King Wen. Thereupon, King Wen received this [Great Mandate?].Footnote 92 Later on, King Wu conquered the Great Settlement Shang, and, staying in the courtyard [of a palace or temple], made an announcement to Heaven, saying: ‘I shall reside in this central region and regulate the people from there!’ Wu hu! You are but minor sons who have no knowledge. Look at [the example of your ancestors,] the patriarchs! Have merits before Heaven! Carry out commands! Respectfully offer sacrifices! May the wise king's reverent virtue satisfy Heaven! Follow me, [and you will have] no regret!” The king completed his announcement. He* was bestowed with thirty bundles of cowries. [I, He*] use [this occasion] to make this treasured sacrificial vessel for Patriarch X. This was the fifth sacrificial year of the king (He zun, JC6014).Footnote 93

隹王初𨝍宅于成周, 復爯珷王豐, 祼自天, 在四月丙戌。王𫌲(誥)宗小子于京室, 曰:『昔在爾考(孝)公氏, 克𠦪 (弼)玟(文)王,  玟王受茲□□(大命?), 唯珷王既克大邑商, 則廷告于天, 曰:「余其宅茲中或(域/國), 自之𧀼 (乂)民!」』烏虖(乎), 爾有唯小子亡戠(識)!視于公氏, 有爵于天, 徹令敬享𢦏 (哉)!叀王龏(恭)德谷(裕)天, 順我不每(敏), 王咸𫌲(誥), 𣄰易(賜)貝卅朋, 用作□公寶尊彝。隹(唯)王五祀。

玟王受茲□□(大命?), 唯珷王既克大邑商, 則廷告于天, 曰:「余其宅茲中或(域/國), 自之𧀼 (乂)民!」』烏虖(乎), 爾有唯小子亡戠(識)!視于公氏, 有爵于天, 徹令敬享𢦏 (哉)!叀王龏(恭)德谷(裕)天, 順我不每(敏), 王咸𫌲(誥), 𣄰易(賜)貝卅朋, 用作□公寶尊彝。隹(唯)王五祀。

The He zun identifies the lineage name of the commissioner's father. The palaeographic character ![]() consists of the graphic element wei 囗 that embraces two illegible elements. Thus, He's lineage name cannot be deciphered. This time, the place of the vessel's discovery provides a hint to He's identity. It was found in the Qian River valley north of Baoji, in the area of activity of the Ze/Yu lineages. Thus, He likely belonged to the same group of the old Zhou elite as the commissioner of the Yi hou Ze gui. The inscription further records that he was one of these whom the king addressed as zong xiao zi 宗小子, “minor sons of the ancestral shrine,” i.e. members of lineages that shared an ancestry and surname with the royal house.Footnote 94 Thus, the He zun equally reflects interactions in the Zhou network of patrilineally related lineages. If my reading of er xiao gong shi 爾考(孝)公氏 as “your pious patriarchs” is correct, the members of this network were expected to behave “piously” regarding the royal lineage.Footnote 95

consists of the graphic element wei 囗 that embraces two illegible elements. Thus, He's lineage name cannot be deciphered. This time, the place of the vessel's discovery provides a hint to He's identity. It was found in the Qian River valley north of Baoji, in the area of activity of the Ze/Yu lineages. Thus, He likely belonged to the same group of the old Zhou elite as the commissioner of the Yi hou Ze gui. The inscription further records that he was one of these whom the king addressed as zong xiao zi 宗小子, “minor sons of the ancestral shrine,” i.e. members of lineages that shared an ancestry and surname with the royal house.Footnote 94 Thus, the He zun equally reflects interactions in the Zhou network of patrilineally related lineages. If my reading of er xiao gong shi 爾考(孝)公氏 as “your pious patriarchs” is correct, the members of this network were expected to behave “piously” regarding the royal lineage.Footnote 95

The main topic of the interaction between the current king and the representatives of subordinated lineages reflected in the He zun was the king's decision to reside in Chengzhou. As other bronze inscriptions reveal, the Zhou kings were moving between their eastern and western residences, personally keeping an eye on their domain.Footnote 96 The He zun records that the current king already spent some time—perhaps several months, a year, or even several years—in Chengzhou and was now returning to the Zhou metropolitan region. There, he gathered his patrilineal relatives for a ritual primarily dedicated to King Wu, though the ritual also served as an occasion to commemorate King Wen and the founders of other lineages who supported the dynasty's founders. Because the king was preparing to leave for Chengzhou for a longer period again, it is understandable that he needed to make sure that his relatives stayed “pious” and loyal during his absence.

The king legitimated his decision to reside in Chengzhou by referring to the will of king Wu and the Mandate received by King Wen. The “present situation” concerned the reproduction of the political order established after the conquest of Shang. Notably, unlike the Yi hou Ze/Yu gui, the He zun does not acknowledge King Cheng's contribution to the conquest. The lack of his mention is one of the reasons why most scholars assume that this inscription dates from King Cheng's reign.Footnote 97 However, as I will demonstrate below, soon after Kings Wen and Wu began to be celebrated as a pair, King Cheng was removed from the conquest narrative. Hence, the absence of a reference to King Cheng does not necessarily suggest an early date for the vessel. The elaborate language and the complex structure of the He zun are among the reasons to suspect that it dates from the reign of King KangFootnote 98 or King Zhao (see more in the Appendix).

The king underlined that King Wu expressed his will in the wake of the conquest and communicated it to Heaven in a highly ritualized setting. The present ritual for King Wu similarly began in Heaven's shrine. The emulation of actions facilitated the transmission of memory about the king-conqueror and the conquest. In this ritual framework, the royal speech comes to the foreground as the medium of memory transmission. The inscription identifies it as a 𫌲 that Ma Chengyuan has interpreted as gao 誥 (“proclamation”).Footnote 99 If his interpretation, which has not yet been challenged, is correct, this inscription may indicate that proclamations represented a specific genre of ritualized speech pronounced in the setting of sacrificial ceremonies in front of an assembled public, thus helping to contextualize the “Proclamations” in the Shang shu. In any case, the character includes the yan 言 (“speech”) element and obviously refers to a speech.

As many authors have already mentioned, the He zun includes such expressions as “conquered the Great Settlement Shang” (ke da yi Shang 克大邑商), “central region” (zhong yu 中或(域)), to “regulate the min (people/external lineages?)” (yi min 乂民). This wording strongly recalls the earliest “Proclamations,” especially, the “Shao gao” 召誥 and the “Luo gao” 洛誥. The He zun thus represents important counter-evidence to Barnard's assumption that parallels with transmitted texts can be regarded as indicators of forgery. Their similarities do not imply that “Proclamations” already existed in their present form and that Western Zhou speakers quoted from them in the same way as Spring and Autumn statesmen or Warring States persuaders. Nevertheless, the He zun witnesses that some rhetorical formulas used to speak about the conquest and the First Kings, became fixed very early. The transmitted “Proclamations” incorporate these as building blocks, reflecting a certain continuity of tradition between the early Zhou time and the time of their composition.Footnote 100

A noteworthy detail of the He zun is that, after having finished his account about King Wu, the king emphasized that his addressees “lack knowledge” or “memory” (wang shi/zhi 亡戠(識)).Footnote 101 He probably referred to the genuine knowledge about the events that he just recalled in his speech, namely the conquest and the actions of King Wu. The zong xiao zi might lack knowledge not simply because they were born later and did not experience the conquest as eyewitnesses, but also because they stood farther from the direct channel of memory transmission within the royal lineage, through which the king acquired his own knowledge. The king now assumed the role of a “bearer of memory,” who personally transmitted the memory of the conquest to the others within a ritual framework instead of entrusting this function to a trained priest, archivist, or historian, as such specialists possibly did not yet exist.

The Da and Xiao Yu ding

Two tripods commissioned by Yu, the head of the Ji-surnamed Nangong lineage, complete the group of inscribed bronzes reflecting the early stages of the production of the cultural memory of the conquest and the first kings. Both vessels were discovered during the 1870s in Licun 禮村, Meixian 郿縣 county, of Shaanxi province.Footnote 102 They are usually regarded as dating from the reign of King Kang,Footnote 103 but they more likely date from the end of the reign of King Mu.Footnote 104 The Da Yu ding (Yu's large cauldron) is one of the largest Western Zhou vessels bearing one of the longest inscriptions.Footnote 105 Several full translations are available.Footnote 106 It is indeed one of the most frequently quoted and well-known inscriptions, which some scholars believe to be a typical example of how the past was used in Zhou political culture.Footnote 107 To the contrary, I regard this inscription as outstanding for the time when it was produced, having only a few comparisons even among later pieces.Footnote 108 The same is true for the Xiao Yu ding 小盂鼎 (Small Yu's cauldron), with more than 390 characters, which has been transmitted only in a rubbing on paper with nearly two fifths of the text illegible.Footnote 109 The latter is usually translated in parts or recounted.Footnote 110 In this subsection, I will begin with Yu's identity, consider the settings in which the foundational memory of Zhou was recalled in his inscriptions, and then point out some differences regarding how this memory was used in different circumstances.

Nangong 南宮 was a metropolitan lineage, descending from Nangong Kuo 南公/宮括. Nan 南 probably corresponds to Nan/Ran/Dan 冄/聃, mentioned in transmitted texts (see Figure 2). Thus, Nangong Kuo was plausibly the same person as Nan/Ran/Dan ji 冄/聃季 (The Junior of Nan/Ran/Dan), i.e. King Wen's youngest son by his primary wife.Footnote 111 This hypothesis, first expressed by Tang Lan, has been confirmed by recently excavated inscriptions from the cemeteries of the Zeng lineage that equally descended from Nangong Kuo, in Yejiashan 葉家山, Wenfengta 文峰塔, and Zaoshulin 棗樹林.Footnote 112 The “Jun Shi” 君奭 chapter of the Shang shu mentions Nangong among King Wen's important aides.Footnote 113 Inscriptions from various reigns witness that the leaders of the Nangong lineage continued playing important roles at the Zhou court during the Western Zhou period. The Nangong lineage further followed King Ping to the east and retained its prominent role until 516 b.c.e., when its leaders, together with the heads of the other old lineages that included the Shao, Mao, and Shan, fled to Chu after the unsuccessful rebellion of wangzi 王子 (Royal Son) Zhao 昭, whom they all supported.Footnote 114 It is likely that his status as the head of this important lineage was the reason why Yu was able to commission particularly large tripods with unprecedentedly long inscriptions, emphasizing his close connection to the reigning king. Yu's patrilineal kinship with the royal house, as well as his direct genealogical relation to King Wen, were probably the reasons why the king, whose speech is quoted in the Da Yu ding, several times referred to the first kings in his address.

Unlike in the case of the He zun, the royal speech quoted in the Da Yu ding was pronounced not at an assembly, but at an individual audience. The king addressed Yu with the highest distinction, enumerating his various achievements. Although the speech also includes a royal command, delegating to Yu the control over considerable military forces, the inscription clearly differs from appointment inscriptions that usually only describe the appointment procedure and content, as well as related gifts. These became widespread only from the reign of King Gong.Footnote 115 The reference to the memory of the first kings appears at the speech's opening:

… The King approvingly said: Yu! Illustrious King Wen received Heaven's blessings [and] the great Mandate. When King Wu gave way to King Wen, he created the bang,Footnote 116 eliminated his foes, broadly possessed the Four Quarters, [and] greatly governed his/their min (external lineages?) (Da Yu ding, JC2837).

… 王若曰:「盂, 丕顯文王受天有(佑)大令, 在武王嗣文作邦, ![]() (闢)厥慝, 匍有四方, 㽙(畯)正厥民 。」

(闢)厥慝, 匍有四方, 㽙(畯)正厥民 。」

As in the case of the He zun, Kings Wen and Wu are commemorated here as a pair, while King Cheng is not mentioned. The current king states that King Wen received the Great Mandate from Heaven, whereas King Wu succeeded him as the heir and created the bang 邦. At the end of the speech, the king encourages Yu to “take as a model his ancestor Nangong” just as he takes Kings Wen and Wu as models.

The situation reflected in the Da Yu ding was certainly politically relevant. By recalling the memory of the conquest, the king underlined the closeness of the royal house and the Nangong lineage. As has already been mentioned, Nangong was not only an important metropolitan lineage, but also had a dependency in a strategically important place—the Zeng 曾 polity in the Suizhou 隨州 corridor in northern Hubei.Footnote 117 Paying respect to this patrilineal relative, the king aimed to secure the loyalty of a high-ranking political ally, and possibly that of the whole network of the Nangong connections extending far beyond the Zhou metropolitan region.

Notably, in contrast to the Yi hou Ze/Yu gui and the He zun, the Da Yu ding avoids the expressions “to conquer” and “to strike,” and does not mention the place-name Shang. Nevertheless, it refers to the conquest, addressing the conquered by the name of the dynasty, Yin 殷:

I have heard that the Yin dropped the Mandate. This was because the hou and dian [lords] on the Yin periphery, as well as Yin administrators and one hundred rulers [all] submitted their will to alcohol and hence ruined their troops. (Da Yu ding, JC2837)

我聞殷述(墜)令, 唯殷邊侯、田(甸)𩁹(與)殷正百辟, 率肄于酉(酒), 古(故)喪𠂤(師)巳。

Many scholars have pointed out that this text is strongly reminiscent of the “Jiu gao” 酒誥 chapter of the Shang shu, allegedly rendering the speech of Zhou gong Dan.Footnote 118 Nevertheless, the propagation of abstinence in a speech—as the conventional dating of Yu's vessels suggests—of King Kang is puzzling considering the great number of zun 尊, yi 彜, you 卣, zhi 觶, and other bronze vessels for alcoholic beverages commissioned during early Zhou reigns. This material evidence suggests that drinking was a widespread and fully legitimate element of the Zhou elite culture. This culture reached its culmination during the reign of King Zhao, as corroborated by inscriptions commemorating libation rituals on exquisite libation vessels.Footnote 119 Archaeologists reveal that this culture started to change about the reign of King Mu or King Gong, as the focus of the assemblages for ancestral rituals and burials shifted from vessels for alcohol to vessels for meats and grain. This major change was probably initiated by the royal court in the context of the so-called “ritual revolution” (Rawson) or “ritual reform” (Falkenhausen).Footnote 120 In light of the revised date of the Da Yu ding, the passage about Yin drunkenness in the inscription on the huge meat cauldron may be understood as an indirect criticism of earlier Zhou practices and as a manifesto of the ritual reform—a major political project for which king Mu likely sought support from the heads of the leading Ji-lineages.

The Xiao Yu ding, commissioned later than the Da Yu ding, commemorates a celebration of Yu's military achievements in the Zhou Temple on the Zhou Plain. In this case, the inscription describes a ritual performance without quoting a royal speech. The king gathered guests from various bang (bang bin 邦賓) to watch the presentation of captives and booty, as well as to attend to the offerings of animal victims and alcoholic beverages to several royal ancestors. These included the King of Zhou, King Wu, and King Cheng (cf. Xiao Yu ding, JC2839). For some reason, King Wen was not mentioned. It is not clear to whom the posthumous title “King of Zhou” referred. This could be Danfu, the founder of the Zhou settlement on the Zhou Plain, or, less probably, his son wang ji. The ceremonial emphasis on kings Wu and Cheng in the frame of a military celebration could be related to their roles as conquerors. This may suggest that there were possibly two different foundational narratives.Footnote 121 The metaphysical narrative linked Heaven to the focal ancestors of the royal house and all lineages descending from it, namely, Kings Wen and Wu, through the notion of the Mandate.Footnote 122 The real-political narrative acknowledged the contributions of King Cheng, during whose reign the conquest of Shang was accomplished and many Zhou polities were effectively founded.Footnote 123 As the following section will demonstrate, the first narrative became dominant in the subsequent royal memory policy.

Even if the conquest of Shang was not mentioned explicitly in the Xiao Yu ding, it is likely that the ritual for Kings Wu and Cheng involved its commemoration. Thus, warfare and the extension of the Zhou military presence into new areas represented another “present setting” in which the memory of the conquest of Shang was recalled.

The inscriptions of Yi hou, He, and Yu corroborate that the conquest of Shang was firmly established as the main point of reference for Ji-surnamed lineages. If the “guests from [various] bang,” participating in celebrations such as those reflected in the Xiao Yu ding, included members of metropolitan lineages of other surnames, those were also encouraged to share this memory. If so, Wang Ming-ke may be right that the shared memory of the conquest helped to generate in-group feelings in the confederation of the lineage-based polities of the Wei river valley. However, it is clear that it primarily served to support the group identity of the Ji.

The situations reflected in the inscriptions considered in this section took place when the generation of the conquest's participants was either very old or had already passed away. The Yi hou Ze gui possibly reflects the stage when the memory about the beginning of the Zhou dynasty was still transmitted orally by the people who personally knew the conquest's participants. The He zun probably derives from the time when the “communicative modus” of transmission was already running into its limits, hence the royal remark that the “minor sons of the ancestral shrine” lack the “knowledge.” It demonstrates that subsequent kings gathered their patrilineal relatives for rituals and instructed them to internalize the memory about the conquest and the first kings. The Da and Xiao Yu ding, if they date from the reign of King Mu, fall beyond the horizon of the Assmanns’ communicative transmission mode. They suggest that the memory of the conquest was recalled in a variety of contexts in connection to various political projects. Altogether, these inscriptions witness that as the foundational past was getting increasingly distant, special efforts were made to preserve it. These can be regarded as elements of a purposeful “memory policy” of the royal court. At the same time, the inscriptions reflect the importance of oral transmission, as they emphasize the acts of speaking (yue 曰, gao 誥) and hearing (wen 聞). The Yi hou Ze gui remains so far the only inscription that suggests the use of images or charts in the memory transmission process.

Commemorating the past was not the main purpose, but an integral element, of the ceremonies described in inscriptions. Although ceremonies that had no objectives other than worshipping the first kings and strengthening the shared identity of the worshippers probably also took place, these are not reflected in inscriptions available so far. Our current evidence thus only relates to the “practical applications” of the cultural memory in distinctively political contexts.

A noteworthy aspect of the Zhou memory policy is that in all available examples, the Zhou kings single-handedly transmitted the memory of the conquest and the first kings without relying on any trained specialists, either priests or archivists. Thus, the involvement of such specialists, as expected by the Assmanns in the context of cultural memory transmission, was not indispensable as long as this process involved a relatively compact metropolitan elite community. The Zhou kings performed divinations using the chart of the conquest, oversaw sacrificial rituals for the first kings, or recited the story of the conquest directly addressing other people collectively or individually. Thus, during the formative period of the Zhou cultural memory, reigning Zhou kings acted as major memory-keeping agents.

The Royal Memory Policy from the Reign of King Gong to the Reign of King Xuan

From the late tenth to the early eighth century b.c.e., only two inscriptions mention the conquest of Shang (or, rather, Yin) explicitly. They will be discussed in the next section. There are slightly more inscriptions that refer to the first kings. Such references constitute part of royal speeches addressed at important political partners. Notably, King Gong (922–900 b.c.e.) conspicuously directed such speeches at lineage outsiders.

One speech from his first year (922 b.c.e.) was addressed at Shi Xun 師訇(詢), whose mother was a Ji-surnamed woman and who, therefore, was a royal affinal relative.Footnote 124 Although the kinship degree between Xun and the King is unclear, the mention of the first kings and the overall trusting tone of the speech, in which the King not only commemorates the support of Xun's ancestors to Kings Wen and Wu, but also shares his worries and concerns about present lack of stability, imply that Xun had a special relationship with the royal house.Footnote 125 Xun probably belonged to the Mi 弭 lineage that may correspond to the Si 姒-surnamed Mi 密 lineage mentioned in transmitted texts.Footnote 126 According to the latter, the Mi lineage had its base in the Jing 涇 valley.Footnote 127 This may explain Xun's appointment as a kind of general-governor (chi guan si 啻官司) in the upper flow of the Jing River, recorded in an inscription from King Gong's seventeenth year (906 b.c.e.).Footnote 128 This inscription equally opens with a royal speech that commemorates the common past:

The King approvingly said: “Xun! Illustrious [Kings] Wen [and] Wu received the Mandate, whereas your ancestors stabilized the Zhou bang. (Xun gui 訇(詢)簋, JC4321)

王若曰:「訇,丕顯文武受令,則乃祖奠周邦.

The king proceeded to delegate to Xun the control of many groups, including trained warriors, both from the west and from Chengzhou.Footnote 129

Between these two events from Xun's biography, the visit of the ruler of Guai  (乖) to King Gong took place in 914 b.c.e. A vessel with a commemorative inscription was probably cast as a gift for Guai bo

(乖) to King Gong took place in 914 b.c.e. A vessel with a commemorative inscription was probably cast as a gift for Guai bo  伯. It equally commemorates the Zhou foundational past and the recipient's ancestors, although in somewhat special terms:

伯. It equally commemorates the Zhou foundational past and the recipient's ancestors, although in somewhat special terms:

The King approvingly said: “Guai bo! My illustrious ancestors King Wen and King Wu received the Great Mandate. Your ancestors were able to visit (?) the former Kings; strangers from another bang, [they] had a share (?) in the Great Mandate. I also do not [meaning unclear, perhaps cease] to enjoy [the possession of the] bang. Give you a [meaning unclear] fur coat!” (Guai bo gui 乖伯簋, JC4331)

王若曰:「 (乖)伯, 朕不(丕)顯祖玟王武王, 膺受大命, 乃祖克𠦪(拜?)先王, 異自它邦, 又𫷄(席?)于大命。我亦弗

(乖)伯, 朕不(丕)顯祖玟王武王, 膺受大命, 乃祖克𠦪(拜?)先王, 異自它邦, 又𫷄(席?)于大命。我亦弗 (享?)邦。易汝𫧊裘。」

(享?)邦。易汝𫧊裘。」

Guai was probably located upstream the Jing River in southern Gansu.Footnote 130 It was likely an old polity that was explicitly referred to as “another bang.” The inscription further celebrates “one hundred relatives by marriage” (bai zhu hun gou 百諸婚媾). This may suggest that Guai belonged to the affinal network of Zhou. Notably, the deceased father of Guai bo was referred to as King Wu Ji of Guai 武乖幾王, thus alluding to King Wu of Zhou as a model.

Both Xun's appointment and the audience of Guai bo were likely related to urgent concerns over stability in the north. This region was about to become the stage of permanent warfare with northern groups who eventually invaded Zhou in 771 b.c.e. and forced the royal house to leave to the east.Footnote 131

During the ninth and early eight centuries, royal speeches alluding to the first kings appear again mostly in inscriptions commissioned by royal patrilineal relatives with great political weight. One of these was Mao gong 毛公, the head of the metropolitan Mao lineage descending from King Wen, the commissioner of the already mentioned Mao gong ding.Footnote 132 It is comparable in content and partly in wording with the Da Yu ding.Footnote 133 Most scholars date it to the reign of King Xuan.Footnote 134 Another eminent recipient of a royal speech was shi Ke 師克, also known as shanfu Ke 善夫克, who was probably a high-ranking member of the metropolitan Ji-surnamed Jing 井 lineage. Ke commissioned a large set of inscribed bronzes, which were discovered in 1890 in Renjiacun 任家村, Fufeng 扶風 county—in the middle of the Zhou Plain. One of his inscriptions, reproduced on several xu 盨 containers, quotes a royal speech containing a reference to Kings Wen and Wu and a command to take over military responsibilities. Another one of Ke's vessels, the Da Ke ding 大克鼎 (the large Ke's cauldron, JC2836), which inscribed with 281 characters and is one of the largest and heaviest Western Zhou tripods, boldly testifies to Ke's own political weight at the Zhou court. Ke's other inscriptions contain precise dates, revealing that he was equally active during the reign of King Xuan, especially during the 812–803 b.c.e.Footnote 135