1. Introduction

This chapter outlines and analyzes the general jurisdiction for the general affairs section of the proposed African Court of Justice and Human Rights (ACJHR) as set out in the Malabo Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (The Malabo Protocol). The chapter focuses in particular on the most general clause of this general jurisdiction referencing ‘Any question of international law’ to examine whether that clause should be read expansively or restrictively in light of the Malabo Protocol especially as regards the ‘ultimate objective’ of the African Union (AU) which is the ambitious progressive federalization agenda. That is to say the legal implications of progressive Pan-Africanization. The proposed court could work in attaining progress towards that ultimate goal but it will take immense collective effort and commitment. This inquiry is important because the general jurisdiction conferred on the General Affairs Section of the Court by necessary implication encompasses all international law matters that are not excluded by either the Human and Peoples’ Rights or the International Criminal Law sections of the Court.

The chapter begins by explaining the provision’s immediate origins in the two preceding protocols going back to reforming the African Court of Justice. The next two sections go on to examine, first, the Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights, and second, the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights. The discussion section draws together the insights gleaned earlier to make the preliminary conclusion that the ‘any question of international law’ clause has to be read in a uniquely restrictive sense in the African context. Having said that, it has the potential scope to be the most litigated clause in the entire instrument given for instance the sheer number, scale and variety of treaties and conventions that would require re-examination should and when the United States of Africa comes into being. The overall argument is that the clause should be read not so much as conferring a specific jurisdiction as such but as restating a preference for legality as an approach to resolving disputes over diplomacy and even the use of force. To place this is a continuum between politics and law, the clause indicates a pendulum swing to the legalization of political disputes as opposed to the politicization of legal disputes.

Speaking of the Malabo protocol provisions on the general jurisdiction of the, at the moment, proposed ACJHR is an intriguing prospect. Not least because that protocol, which is not yet in force, amends an earlier protocol which is itself not yet in force, and indeed will never be in force except in the form and content of the new provisions once they enter into force. This renders it necessary to delve into the history of the provisions as well as speculate upon its future application. These are two strikingly different approaches. The first has a trajectory that moves from the present backwards, and the second moves from the present forwards. The first is genealogy while the second is speculation, if you like. Not law as it is nor law as it should be, but law as it shall be.

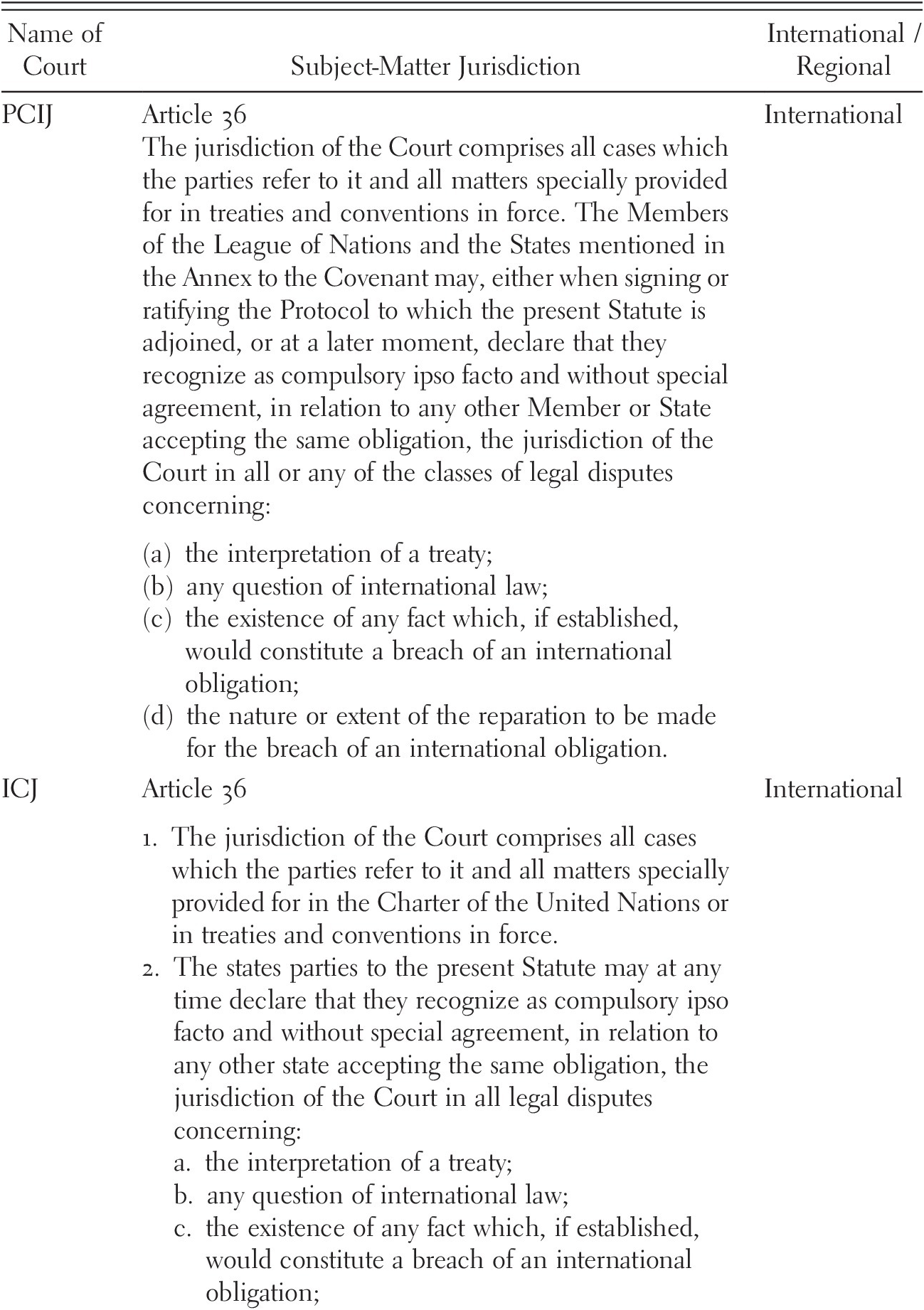

Methodologically, the approach favoured is as a consequence doctrinal – from a comparative and historical perspective. That is to say to compare as well as contrast the proposed court with a similar institution or institutions. As we shall see, these include – in this specific instance – the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and possibly the European Court of Justice (ECJ). The similarities are chiefly along the lines of subject matter jurisdiction as well as certain equivalences in origin. These go beyond the AU matching up semantically with the European Union (EU) and their resultant courts of justice (although these of course cannot be dismissed as merely coincidental), but the history of amendments of the Nice and Lisbon treaties in the case of the ECJ and the Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights and second the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights in the case of the ACJHR. Furthermore, the transition from the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) also has some bearing on the matter. As a consequence, the PCIJ, the ICJ the ECJ could be possible sources among others of persuasive precedent for the ACJHR in interpreting and construing what ‘any question of international law’ means once the court is established. This court itself would be a mega-court jurisdictionally combining, as it does, the jurisdiction of the ICJ in its General Affairs Section, The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in its Human and Peoples’ Rights and the International Criminal Court (ICC) in its International Criminal Law Section. The table below comparing the PCIJ/ICJ, and ACJHR illustrates this point:

Table 35.1 Comparative Chart PCIJ/ICJ, and ACJHR

| Name of Court | Subject-Matter Jurisdiction | International /Regional |

|---|---|---|

| PCIJ | Article 36 | International |

The jurisdiction of the Court comprises all cases which the parties refer to it and all matters specially provided for in treaties and conventions in force. The Members of the League of Nations and the States mentioned in the Annex to the Covenant may, either when signing or ratifying the Protocol to which the present Statute is adjoined, or at a later moment, declare that they recognize as compulsory ipso facto and without special agreement, in relation to any other Member or State accepting the same obligation, the jurisdiction of the Court in all or any of the classes of legal disputes concerning:

| ||

| ICJ | Article 36

| International |

| ACJHR | The Court shall have jurisdiction over all cases and all legal disputes submitted to it in accordance with the present Statute which relate to:

| Regional |

From a historical perspective it is clear too that the evolution of the point was actually intended to encourage the peaceful settlement of disputes through the medium of law as opposed to diplomacy and a fortiori the use of military force. The table below demonstrates the gradual development of the clause as progressively encouraging the use of law over diplomacy and even war:

| Article 16 1899 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes | In questions of a legal nature, and especially in the interpretation or application of International Conventions, arbitration is recognized by the Signatory Powers as the most effective, and at the same time the most equitable, means of settling disputes which diplomacy has failed to settle. |

| Article 38 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes | In questions of a legal nature, and especially in the interpretation or application of International Conventions, arbitration is recognized by the Contracting Powers as the most effective, and, at the same time, the most equitable means of settling disputes which diplomacy has failed to settle. |

| Consequently, it would be desirable that, in disputes about the above-mentioned questions, the Contracting Powers should, if the case arose, have recourse to arbitration, in so far as circumstances permit. | |

| Article 13 The Covenant of the League of Nations | The Members of the League agree that whenever any dispute shall arise between them which they recognize to be suitable for submission to arbitration or judicial settlement and which cannot be satisfactorily settled by diplomacy, they will submit the whole subject matter to arbitration or judicial settlement. |

| Disputes as to the interpretation of a treaty, as to any question of international law, as to the existence of any fact which if established would constitute a breach of any international obligation, or as to the extent and nature of the reparation to be made for any such breach, are declared to be among those which are generally suitable for submission to arbitration or judicial settlement. | |

| For the consideration of any such dispute, the court to which the case is referred shall be the Permanent Court of International Justice, established in accordance with Article 14, or any tribunal agreed on by the parties to the dispute or stipulated in any convention existing between them. | |

| The Members of the League agree that they will carry out in full good faith any award or decision that may be rendered, and that they will not resort to war against a Member of the League which complies therewith. In the event of any failure to carry out such an award or decision, the Council shall propose what steps should be taken to give effect thereto. | |

| Article 36 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice (excerpt) |

|

The developmental arc ends with judicial settlement of international disputes. The decisions of the ICJ, and in particular the Nicaragua (Merits) Case,Footnote 1 then becomes the principal source of law for the ACJHR.

2. Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (Malabo Protocol) 2014

As is customary, although the preamble does not have the force of law, it nevertheless sets out the background, overall context, and intent of the document. This is important because customary international law is a necessary resource given the varying status of the separate body of documents that make up the relevant body of law, as well as the generality of the statement ‘any question of international law’ which goes beyond treaty law.

In the preamble the Member States of the African Union whom are the parties to the Constitutive Act of the African Union recall the objectives and principles enunciated in the Constitutive Act that was adopted on 11 July 2000 in Lome, Togo. That rather general statement is linked to a less general one which nevertheless vaguely references the commitment to peaceful settlement of disputes. This reference to ‘peaceful settlement of disputes’ is key to understanding the genealogy of the phrase ‘any question of international law’. It first occurred in the form ‘questions of a legal nature’ under Article 16 of the 1899 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. It reappeared in identical form in Article 38 of the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. Its present form first appeared in Article 13 of the Covenant of the League of Nations and then in Article 36 of both the Statute of the International Court of Justice and that of the Permanent Court of International Justice. There is no equivalent clause in either the Treaty on European Union or the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union. This renders their resultant case law not as relevant as, for instance the ICJ, even though the ECJ is, like the ACJHR, also a regional court.

A rather more specific statement on the provisions of the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights and the Statute annexed immediately follows this recollection to it that was adopted on 1 July 2008 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. The Member States go on to recognize that the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights had merged the African Court on Human and Peoples Rights and the Court of Justice of the African Union into a single court. Along with this the Member States bear in mind their collective commitment to promote peace, security and stability on the African continent, and likewise to protect human and people’s rights in accordance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights and other relevant instruments.

The Member States made a point to acknowledge the pivotal role that the African Court of Justice and Human and Peoples Rights can play in strengthening the commitment of the African Union to promote sustained peace, security, and stability on the Continent, and to promote justice and human and peoples’ rights as an aspect of their efforts to promote the objectives of the political and socio-economic integration and development of the Continent with a view to realizing the ultimate objective of a United States of Africa.

There are seventeen new articles inserted by the Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights that grant the Court international criminal jurisdiction. However, it is its general jurisdiction that specifically interests us particularly as spelt out in the Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights beginning in Article 3 setting out the Court’s Jurisdiction as:

1. The Court is vested with an original and appellate jurisdiction, including international criminal jurisdiction, which it shall exercise in accordance with the provisions of the Statute annexed hereto.

2. The Court has jurisdiction to hear such other matters or appeals as may be referred to it in any other agreements that the Member States or the Regional Economic Communities or other international organizations recognized by the African Union may conclude among themselves, or with the Union.

It is imperative therefore to examine the provisions of the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights as both protocols have to be read more or less side-by-side to be given both effect and meaning.

3. Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (Sharm El Sheikh Protocol), 2008

The first chapter of the Sharm El Sheikh Protocol merges the African Court On Human and Peoples’ Rights with the Court of Justice of The African Union. Article 1 replaces the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, adopted on 10 June 1998 in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso (entry into force 25 January 2004), and the Protocol of the Court of Justice of the African Union, adopted on 11 July 2003 in Maputo, Mozambique. Article 2 then goes on to establish a single Court, the ‘African Court of Justice and Human Rights’. For removal of doubt Article 3 provides that any references made to the ‘Court of Justice’ in the Constitutive Act of the African Union shall be read as references to the ‘African Court of Justice and Human Rights’.

Crucially, in the very first article of the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights contained in the Annex to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights ‘Section’ has now been sought to be amended to mean either the General Affairs, or Human and Peoples’ Rights, or International Criminal Law Section of the Court.

Article 28, which provides the jurisdiction of the court, will as a consequence now have to be read down with the Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights in mind. It is reproduced below with the affected bits of its text either struck out or amended with underlining wherever appears necessary:

The General Section of the Court shall [with the following exceptions] have jurisdiction over all cases and all legal disputes submitted to it in accordance with the present Statute which relate to:

a) the interpretation and application of the Constitutive Act;

b) the interpretation, application or validity of other Union Treaties and all subsidiary legal instruments adopted within the framework of the Union or the Organization of African Unity excluding questions of either international criminal law or international human rights law;

c) the interpretation and the application of the African Charter, the Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, or any other legal instrument relating to human rights, ratified by the States Parties concerned;

d) any question of international law [excluding questions of either international criminal law or international human rights law];

e) all acts, decisions, regulations and directives of the organs of the Union [excluding questions of either international criminal law or international human rights law];

f) all matters specifically provided for in any other agreements that States Parties may conclude among themselves, or with the Union and which confer jurisdiction on the Court [excluding questions of either international criminal law or international human rights law];

g) the existence of any fact which, if established, would constitute a breach of an obligation owed to a State Party or to the Union [excluding questions of either international criminal law or international human rights law];

h) the nature or extent of the reparation to be made for the breach of an international obligation [excluding questions of either international criminal law or international human rights law].

4. Discussion and Argument

The fact that a dispute contains a legal question does not exclude politics. The weight of the authorities both judicial and academic weigh onto the side that a legal question when taken as one that is amenable to legal resolution references the jurisdictional capacity of a judicial organ as opposed to a political organ. Which is to say that just because a question has political aspects that would not preclude a court from making a final determination over the matter.

Indeed the ICJ noted in the Hostages Case (Merits) ‘legal disputes between sovereign States by their very nature are likely to occur in political contexts, and often form only one element in a wider and longstanding political dispute between the States concerned’.Footnote 2

Hersch Lauterpacht writing in 1933 about the PCIJ made the point that under a clause conferring jurisdiction to decide ‘any question of international law’ a court of justice was empowered to deal with the customary international law doctrine of rebus sic stantibus or a fundamental change of circumstance.Footnote 3 This clause includes not just legal interpretation but also the ascertainment as well as consideration of facts. Indeed, for Lauterpacht ‘any question of international law’ could conceivably cover all possible disputes that states can submit to an international judicial tribunal. He therefore argued against a one-sided or restrictive interpretation. His position of course cannot be applied to the equivalent clause in the ACJHR without qualification principally because both international criminal law questions and international human rights law questions are excluded from the general jurisdiction of the general section of that court. Nevertheless, the question of examining a fundamental change of circumstance rendering a treaty or treaties inapplicable is still a very wide and powerful judicial discretion that deserves further study, and perhaps even invocation, as states are expected to dissolve themselves as independent sovereign entities to a single United States of Africa.

Writing in 1924 of the distinction between legal and political questions, Charles Fenwick expressed the view that legal questions were those governed by a more or less ascertainable rule of law.Footnote 4 For him, these were synonymous with justiciable questions, which were those that could be properly submitted to a judicial tribunal.Footnote 5 Quincy Wright, in speaking of the same distinction, preferred to look at it in instrumental function in distinguishing ‘legal from political questions as those questions in which more interests will be satisfied by a settlement according to law than by some other mode of settlement.’Footnote 6 This formulation has the advantage of bringing in the language of the Hague conference.

In the first advisory opinion of the ICJ on the Conditions of Admission of a State to Membership in the United Nations (Article 4 of the Charter), The Court found that it could not ‘attribute a political character to a request which, framed in abstract terms, invites it to undertake an essentially judicial task, the interpretation of a treaty provision’.Footnote 7 Erika de Wet finds that distinguishing between legal and political questions is unimportant when compared to distinguishing between legal and political methods in determining disputes. For her ‘a legal dispute implies both a legal and political answer’ to the same question.Footnote 8 For Lauterpacht, because there was ‘no fixed limit to the possibilities of judicial settlement’, all international political conflicts were reducible ‘to contests of a legal nature’, therefore, the ‘decisive test’ for justiciability of a dispute would the willingness of the parties to submit to legal arbitration.Footnote 9 David S. Patterson found that the impetus for a world court came from lawyers who wanted the United States to lead in the quest for pacific alternatives to international violence.Footnote 10 Akande elegantly phrases this important point in the double negative: ‘The Statute in no way excludes any question of international law from the consideration of the Court in cases in which it has jurisdiction’.Footnote 11 For him, as long as the Court has jurisdiction over a legal question before it then it ‘has a duty to decide the matter’ notwithstanding that another political organ may have the same matter before it.Footnote 12 Just because a political institution has been seized of jurisdiction does not preclude the court’s jurisdiction over the same matter.Footnote 13

This is why international courts and tribunals could say that:

The doctrines of ‘political questions’ and ‘non-justiciable disputes’ are remnants of the reservations of ‘sovereignty’, ‘national honour’, etc., in very old arbitration treaties. They have receded from the horizon of contemporary international law, except for the occasional invocation of the ‘political question’ argument before the International Court of Justice in advisory proceedings and, very rarely, in contentious proceedings as well. The Court has consistently rejected this argument as a bar to examining a case. It considered it unfounded in law.Footnote 14

Dissenting and separate opinions ‘however political be the question, there is always value in the clarification of the law. It is not ineffective, pointless and inconsequential’Footnote 15 ‘[D]ecision can contribute to the prevention of war by ensuring respect for the law’.Footnote 16 The political aspects of the dispute may make legal determination all the more urgent:

Indeed, in situations in which political considerations are prominent it may be particularly necessary for an international organization to obtain an advisory opinion from the Court as to the legal principles applicable with respect to the matter under debate.Footnote 17

The ACJHR’s General Jurisdiction for General Affairs cannot therefore be an exception to the ever expanding contemporary dynamic of political disputes being rendered amendable to legal adjudication.

The extension of the African Court’s jurisdiction to disputes between the African Union and its staff members is an anomaly in the order of international and regional courts, as these courts rarely adjudicate internal disputes between international organizations and their staff members. The body of law which governs such disputes is known as international administrative law or international civil service law, and it has developed over the last eighty-plus years through the tribunals created by these organizations. Since organizations such as the United Nations and the African Union enjoy jurisdictional immunities, national courts are limited in their ability to protect the labour rights of international civil servants - employees of these organizations. The development of internal justice systems that include an independent judicial body therefore became a necessary balance to the immunities enjoyed by these organizations. In The Effects of Awards of Compensation Made by the United Nations Administrative Tribunal, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) held that it would ‘hardly be consistent with the expressed aim of the Charter to promote freedom and justice for individuals and with the constant preoccupation of the United Nations Organization to promote this aim that it should afford no judicial or arbitral remedy to its own staff for the settlement of any disputes which may arise between it and them.’Footnote 1

In 1966 the Organization of African Unity (OAU), predecessor to the African Union, established an Administrative Tribunal noting that ‘the service relations in the Organization must be regulated only by internal rules of the Organization, any competence of national courts being excluded.’Footnote 2 This Tribunal, which now operates as the African Union Administrative Tribunal (AUAT), is competent to receive applications from staff members of the African Union alleging non-observance of contracts of employment or violations of the provisions of the Staff Regulations and Rules by the organization. In a manner similar to a national court, the AUAT issues binding decisions which include remedies to compensate the aggrieved staff member. With the inclusion of Article 29(1)(c) in the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (The Protocol), employees of the African Union and its organs now have the unprecedented right to appeal decisions of the AUAT to the region’s highest court – the African Court of Justice and Human Rights.

This chapter offers initial observations on the inclusion of an appellate jurisdiction over international administrative law in the Statute of the African Court. It will first set out the legal framework and historical context for this provision, and further assess four main observations on the exercise of this jurisdiction.

1. Legal Framework and Historical Context

To understand the context in which the African Court exercises jurisdiction over administrative law matters, Article 29(1)(c) of the Protocol is best read in conjunction with Rule 62 of the 2010 African Union Staff Regulations and Rules. Pursuant to Rule 62.1, a staff member of the African Union may submit an application to the AUATFootnote 3 contesting administrative and disciplinary decisions by the organization taken against him or her. The AUAT is competent to hear ‘appeals submitted by staff members or their beneficiaries, alleging violations of the terms of appointment, including all applicable provisions of the Staff Regulations and Rules, or appeals against administrative and disciplinary measures.’Footnote 4 Recourse to the Tribunal forms an internal remedy, the exhaustion of which is necessary before a staff member can approach the African Court. Rule 62.3 of the Staff Regulations and Rules provides that:

In the event of breach of contract of employment or violation of these Regulations and Rules, a staff member who has exhausted all the internal procedures provided for by these Regulations and Rules, shall file within sixty (60) days from the date of judgment, an appeal to the African Union’s Court of Justice and Human Rights.

Article 29(1)(c) of the Protocol cements this right of appeal by noting that:

The following entities shall be entitled to submit cases to the Court on any issue or dispute provided for in Article 28:

[…]

c) A staff member of the African Union on appeal, in a dispute and within the limits and under the terms and conditions laid down in the Staff Rules and Regulations of the Union.

These provisions in Article 29(1)(c) of the Protocol and Rule 62 of the Staff Regulations and Rules represent two significant changes in the processes available to address disputes between staff members and organs of the African Union. First, prior to the 2010 Staff Regulations and Rules, the 1993 OAU Staff Regulations & Rules provided a different form of dispute settlement. In contesting an administrative decision, the then ad hoc Administrative Tribunal represented the final recourse available to staff members challenging the organization’s alleged non-observance of the Staff Rules or terms of employment. Such finality in its decisions is a common feature in the statutes of the tribunals of other international organizations such as the World Bank,Footnote 5 the African Development BankFootnote 6 and the International Labour Organization,Footnote 7 which exercises jurisdiction over employment disputes in more than sixty international organizations and some UN agencies.

Under the OAU Staff Regulations & Rules, the staff member in question was first required to ‘address a letter to the Secretary-General requesting that the administrative decision in question be reviewed.’Footnote 8 If the Secretary-General confirmed the decision, or if the staff member received no response within thirty days of his/her letter, the staff member ‘shall be entitled to file, within a further thirty days, an appeal with the Administrative Tribunal in the form prescribed in the Tribunal’s Rules of Procedure […].’Footnote 9

The opportunity to appeal the Tribunal’s decision to a higher body was non-existent. This proved immensely problematic as the AUAT was non-operational between 1999 and 2014, denying staff members the judicial resolution of their employment disputes.Footnote 10 This matter was expressly addressed in the 30 September 2011 decision of the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) in the matter of Efoua Mbozo’o Samuel v. The Pan African Parliament.Footnote 11

On 6 June 2011, Mr. Efoua Mbozo’o filed a case before the ACHPR against the Pan African Parliament alleging breach of paragraph 4 of his contract of employment and of Articles 13(a)Footnote 12 and (b)Footnote 13 of the OAU Staff Regulations & Rules. He also claimed there was an improper refusal to renew his employment contract and ‘re-grade’ him. When prompted by the ACHPR Registrar to specify the human rights violations he alleged, the Applicant responded by making further submissions underlining allegations of breach by the Pan African Parliament which included:

a. Paragraph 4 of his contract of Employment and Article 13(a) and (b) of the OAU Staff regulations by refusing to renew his contract and advertising his post even though he had satisfactory evaluation reports; and

b. Executive Council Decision EX.CL/DEC 348 (XI) of June 2007 with regard to the remuneration and grading of his employment.

In finding that it lacked jurisdiction to hear the case, the ACHPR held that:Footnote 14

5. Article 3(1) of the Protocol provides that “the jurisdiction of the Court shall extend to all cases and disputes submitted to it concerning the interpretation and application of the Charter, this Protocol and any other relevant Human Rights instrument ratified by the States concerned”.

6. On the facts of this case and the prayers sought by the Applicant, it is clear that this application is exclusively grounded upon breach of employment contract in accordance with Article 13 (a) and (b) of the OAU Staff Regulations, for which the Court lacks jurisdiction in terms of Article 3 of the Protocol. This is therefore a case which, in terms of the OAU Staff Regulations, is within the competence of the Ad hoc Administrative Tribunal of the African Union. Further, in accordance with Article 29(1)(c) of its Protocol, the Court with jurisdiction over any appeals from this Ad hoc Administrative Tribunal is the African Court of Justice and Human Rights. The present Court therefore concludes that, manifestly it doesn’t have the jurisdiction to hear the application.

The Protocol on the African Court had not entered into force at the time of Mr. Efoua Mbozo’o’s application, and is still yet to do so. The ACHPR centred its decision on its apparent lack of subject matter jurisdiction (ratione materiae). While the ACHPR did not expressly state so, it also clearly lacked jurisdiction ratione personae given that it has jurisdiction only over complaints against States Parties to the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and not complaints against regional institutions or their organs. A matter which Justice Fatsah Ouguergouz addressed in his Separate Opinion.Footnote 15 Justice Ouguergouz further highlighted certain aspects of the Application which stressed the inaccessibility of AU staff members to an effective internal justice mechanism. He observed that:Footnote 16

In his application, as supplemented by his letter of 22 August 2011, the Applicant indeed draws the attention of the Court to an appeal which he reportedly lodged before the Ad Hoc Administrative Tribunal of the African Union on 29 January 2009. On 15 April 2009, this appeal is reported to have been declared admissible by the Acting Secretary of the Tribunal and on 29 September 2010, after many reminders addressed to the latter, the Applicant is said to have been informed that the Tribunal ‘had not been able to sit for the last 10 (ten) years due to inadequate financial means and due to the fact that the Tribunal did not have any Secretaries.’ The Applicant purports that two years and four months after his appeal was declared admissible, the Tribunal was still to sit and that it is due to the ‘silence’ of the latter that he decided to refer the matter to the Court.

Mr. Efoua Mbozo’o, like other staff members in his position, was denied access to a justice mechanism to address his dispute with the African Union. The ad hoc Administrative Tribunal was, to use the words of the then Chairman of the AU Commission, ‘long-moribund,’Footnote 17 and the ACHPR, even if it had jurisdiction over the Applicant’s claim, did not consider whether this denial of access amounted to a human rights violation.Footnote 18

The second significant change resulting from Article 29(1)(c) of the Protocol is a change in persons eligible to submit cases to the African Court in its capacity as an appellate body reviewing decisions of the AUAT. Article 29(1)(c) is derived from Article 18(1)(c) of the 2003 Protocol of the Court of Justice of the African Union which provides that:Footnote 19

1. The following are entitled to submit cases to the Court:

[…]

(c) The Commission or a member of staff of the Commission in the dispute between them within the limits and under the conditions laid down in the Staff Rules and Regulations of the Union. [Emphasis added].

Conspicuously missing from Article 29(1)(c) is that the African Union Commission, which represents the AU organs in employment disputes, is equally eligible to appeal decisions of the AUAT. This omission is significant for the reasons stated in the observations below.

2. Observations on the Court’s Appellate Jurisdiction in International Administrative Law

A. Unequal Access to the African Court

The AU Commission’s exclusion from the Court’s jurisdiction represents an interesting twist in the discourse and debate on procedural inequality in the rare appeal of decisions by administrative tribunals, which are otherwise intended to be final and binding. This discussion revolves around the fact that previously, under the Statute of the Administrative Tribunal of the International Labour Organization (ILOAT), organizations which were dissatisfied with the decision of the Tribunal could submit a request to the ICJ for an Advisory Opinion to review the decision of the ILOAT.Footnote 20 In its request, the organization either challenged ‘a decision of the Tribunal confirming its jurisdiction’, or ‘considered that a decision by the Tribunal is vitiated by a fundamental fault in the procedure followed’.Footnote 21 The staff member, however, did not have the same right or access to the ICJ.

In its 1956 Advisory Opinion on Judgments of the Administrative Tribunal of the I.L.O. upon complaints made against the U. N. E.S. C. O.,Footnote 22 the ICJ made the following observation about this inequality of access:Footnote 23

According to generally accepted practice, legal remedies against a judgment are equally open to either party. In this respect each possesses equal rights for the submission of its case to the tribunal called upon to examine the matter. This concept of the equality of parties to judicial proceedings finds, in a different sphere, an expression in Article 35, paragraph 2, of the Statute of the Court which, when providing that the Security Council shall lay down the conditions under which the Court shall be open to States not parties to the Statute, adds “but in no case shall such conditions place the parties in a position of inequality before the Court.” However, the advisory proceedings which have been instituted in the present case involve a certain absence of equality between Unesco and the officials both in the origin and in the progress of those proceedings. In the first place, in challenging the four Judgments and applying to the Court, the Executive Board availed itself of a legal remedy which was open to it alone. Officials have no such remedy against the Judgments of the Administrative Tribunal. Notwithstanding its limited scope, Article XII of the Statute of the Administrative Tribunal in this respect confers an exclusive right on the Executive Board.

This matter arose once again in 2010 when the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) submitted a request for an Advisory Opinion to the ICJ, challenging the decision rendered by the ILOAT in Judgment No. 2867, and questioning the validity of that Judgment.Footnote 24 The ICJ observed that the development of the principles of equality of access may be seen in Article 14(1) of the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which provides that ‘[a]ll persons shall be equal before the courts and tribunals.’ In its General Comment on this Article, the Human Rights Committee in 2007 noted that this right guarantees equal access and equality of arms. The ICJ held that:Footnote 25

While in non-criminal matters the right of equal access does not address the issue of the right of appeal, if procedural rights are accorded they must be provided to all the parties unless distinctions can be justified on objective and reasonable grounds […]. In the case of the ILOAT, the Court is unable to see any such justification for the provision for review of the Tribunal’s decisions which favours the employer to the disadvantage of the staff member.”

The ICJ recalled its 1956 Advisory Opinion in which it held that ‘[t]he principle of equality of the parties follows from the requirements of good administration of justice.’Footnote 26 It further emphasized that this principle ‘must now be understood as including access on an equal basis to available appellate or similar remedies unless an exception can be justified on objective and reasonable grounds.’Footnote 27

The matter at hand is whether the inequality of access to the African Court can be justified on objective and reasonable grounds. There are no public travaux préparatoires or explanatory comments to shed light on the reasoning behind the removal of the African Union Commission’s access to the African Court in employment disputes. This is unfortunate as the changes made are significant. On the one hand, one could contend that staff members are generally at a disadvantage since they do not readily have access to a litigation department, so provision of an additional procedural right of appeal levels the playing field. However, on the other hand, the inability of one party to challenge a decision which can freely be challenged by the other party connotes an image of inequality and unfairness in the process, regardless of who the disenfranchised party is.

In performing its functions as an appellate body on administrative law matters, the African Court operates akin to the United Nations Appeals Tribunal (UNAT). In 2009, the United Nations General Assembly introduced a new system for handling internal disputes and disciplinary matters. In redesigning the UN system of administration of justice, a two-tier judicial system was created with judges serving on the UN Dispute Tribunal (UNDT) and on the UNAT. Under this system, both staff members and the administration can appeal a decision by the UNDT to the UNAT.

At the ICJ, the Court attempted to cure the inequality of access by providing equal opportunity for the parties to address the issues before it. This meant providing the staff member with the opportunity to comment and bring statements to the attention of the ICJ. The ICJ further determined that there would be no oral proceedings since the Statute of the ICJ does not permit individuals to appear before it.

It is indeed laudable that the Statute of the African Court provides staff members of the AU with the right to appeal to the region’s highest court. That they are provided this unique standing before the African Court is worthy of recognition. Article 29(1)(c) falls short, however, with the exclusion of the organization from this appeal mechanism. Should Article 29(1)(c) remain un-amended to include the African Commission, the African Court would need to take steps to ensure that the views of the organization concerned are heard and addressed on an equal footing as the staff member in light of the fact that any appellate judgment is binding on the organization.

B. Scope of the African Court’s Appellate Jurisdiction

The next issue to be explored is the scope of the African Court’s appellate jurisdiction. Article 29(1)(c) of the Protocol does not elaborate on this matter, merely providing that the staff member’s appeal must be ‘within the limits and under the terms and conditions laid down in the Staff Rules and Regulations of the Union.’ Rule 62.3 of the AU Staff Regulations also does not address the scope of the African Court’s appellate review; rather it notes the subject matter of the appeal must be allegations of breach of the employment contract or violation of the Staff Regulations and Rules. It thereby appears that the scope of the African Court’s appellate jurisdiction is unrestricted, and the Court may, in theory, conduct a de novo review of the merits of each application submitted on appeal.

Such a broad scope is noteworthy in light of the fact that other judicial bodies with a similar appellate function are limited in their scope of review. For instance, the UNAT which is competent to hear and pass judgment on an appeal filed against a judgment rendered by the UNDT, is only able to review assertions that the UNDT:Footnote 28

(a) Exceeded its jurisdiction or competence;

(b) Failed to exercise jurisdiction vested in it;

(c) Erred on a question of law;

(d) Committed an error in procedure, such as to affect the decision of the case; or

(e) Erred on a question of fact, resulting in a manifestly unreasonable decision.

Furthermore, the power of the ICJ to review a judgment of the ILOAT by reference to Article XII of the Annex to the Statute of the ILOAT was limited to two clearly defined scenarios. First, that the ILOAT wrongly confirmed its jurisdiction, or second, that the decision is vitiated by a fundamental fault in the procedure followed.Footnote 29 In its 1956 Advisory Opinion on Judgments of the Administrative Tribunal of the I.L.O., the ICJ held that the ‘[r]equest for an Advisory Opinion under Article XII is not in the nature of an appeal on the merits of the judgment. It is limited to a challenge of the decision of the Tribunal confirming its jurisdiction or to cases of fundamental fault of procedure. Apart from this, there is no remedy against decisions of the Administrative Tribunal.’Footnote 30

At first glance, a broad scope of review may be appealing, particularly to the staff member who would have another opportunity to plead his or her case. Yet, such a broad scope further undermines the finality of the AUAT’s judgment, which as detailed above, would otherwise be binding. Elaborating on the finality of its judgments, the World Bank Administrative Tribunal (WBAT) stated in van Gent (No. 2):Footnote 31

Article XI lays down the general principle of the finality of all judgments of the Tribunal. It explicitly stipulates that judgments shall be “final and without appeal.” No party to a dispute before the Tribunal may, therefore, bring his case back to the Tribunal for a second round of litigation, no matter how dissatisfied he may be with the pronouncement of the Tribunal or its considerations. The Tribunal’s judgment is meant to be the last step along the path of settling disputes arising between the Bank and the members of its staff.

The WBAT also stated in Mpoy-Kamulayi (No. 7) that: ‘This rule of finality of the Tribunal’s judgments is essential to the operation of the Bank’s internal justice system. Once the Tribunal has spoken, that must end the matter; no one must be allowed to look back to search for grounds for further litigation.’Footnote 32 That concept of finality is enshrined in the 1967 Statute of the ad hoc Administrative Tribunal of the OAU which the AUAT appears to still utilize.Footnote 33 Article 17(vi) of that Statute provides for the finality of the Tribunal’s decisions subject to an application by any party for review upon the discovery of a new fact of a decisive nature,Footnote 34 or for annulment on specific grounds.Footnote 35 With the introduction of Article 29(1)(c) and Rule 63, a staff member appears to also have the right to a second decision on the merits of their case.

In performing its appellate review of the AUAT’s decisions, it is recommended that the African Court establishes specific rules on the scope of this review. First, it may be guided by the functioning of its appellate review in its International Criminal Law Section. The new Article 18 of the Court’s Statute, contained in the Amendments Protocol,Footnote 36 provides that:

In the case of the International Criminal Law Section, a decision of the Pre-Trial Chamber or the Trial Chamber may be appealed against by the Prosecutor or the accused, on the following grounds: (a) A procedural error; (b) An error of law; (c) An error of fact.

An appeal may be made against a decision on jurisdiction or admissibility of a case, an acquittal or a conviction.

The Appellate Chamber may affirm, reverse or revise the decision appealed against. The decision of the Appellate Chamber shall be final.

The basis of previous appeals to the ICJ from the ILOAT could also serve as further guidance to the African Court. As noted above, an organization was previously ale to challenge the ILOAT’s decision confirming its jurisdiction, or contend that the decision is ‘vitiated by a fundamental fault in the procedure followed’. It is useful to note, as the ICJ did, that a ‘challenge of a decision confirming jurisdiction cannot properly be transformed into a procedure against the manner in which jurisdiction has been exercised or against the substance of the decision.’Footnote 37 Furthermore, addressing an appeal on the grounds that the ILOAT made a ‘fundamental error in procedure,’ the ICJ observed in its 1973 Advisory Opinion on Application for Review of Judgment No. 158 of the United Nations Administrative Tribunal, paragraph 92, that while it may not be easy to exhaustively state what is involved in the concept of a ‘fundamental error in procedure which has occasioned a failure of justice,’ the essence of this ground for appeal:

may be found in the fundamental right of a staff member to present his case, either orally or in writing, and to have it considered by the Tribunal before it determines his rights. An error in procedure is fundamental and constitutes “a failure of justice” when it is of such a kind as to violate the official’s right to a fair hearing as above defined and in that sense to deprive him of justice. … [C]ertain elements of the right to a fair hearing are well recognized and provide criteria helpful in identifying fundamental errors in procedure which have occasioned a failure of justice: for instance, the right to an independent and impartial tribunal established by law; the right to have the case heard and determined within a reasonable time; the right to a reasonable opportunity to present the case to the tribunal and to comment upon the opponent’s case; the right to equality in the proceedings vis-à-vis the opponent; and the right to a reasoned decision.

Article 2(1) of the UNAT’s Statute also lays down concrete grounds of appeal which the African Court may wish to consider:

The Appeals Tribunal shall be competent to hear and pass judgement on an appeal filed against a judgement rendered by the United Nations Dispute Tribunal in which it is asserted that the Dispute Tribunal has:

(a) Exceeded its jurisdiction or competence;

(b) Failed to exercise jurisdiction vested in it;

(c) Erred on a question of law;

(d) Committed an error in procedure, such as to affect the decision of the case; or

(e) Erred on a question of fact, resulting in a manifestly unreasonable decision.

Finally, the African Court may also be guided by Article 21 of the Statute of the ad hoc Administrative Tribunal which provides grounds for a request for an annulment of the Tribunal’s judgment. It is unclear whether the Tribunal has conducted such a review in the past given the limited information available on its decisions prior to 2014, and the fact that it was non-operational for over a decade. With the introduction of an appeal in the legal regime governing employment matters at the African Union, it is curious to discover how the annulment process in Article 21 will operate alongside the right of appeal.

It is proposed that once the Statute of the African Court enters into force, the Court should adopt rules which consolidate and address any discrepancies in the implementation of its appellate jurisdiction. It is recommended first, that Article 29(1)(c) of the Statute be amended to permit appeals from the AU Commission. It is further recommended that the text of Article 21 of the ad hoc Administrative Tribunal’s Statute, as well as the grounds described above, be merged to establish a concrete scope of the Court’s appellate jurisdiction over decisions of the AUAT. These concrete grounds could be contained in the Court’s Rules and Procedures to avoid further amendments of its Statute.

C. Applicable Law

This section addresses the sources of law which the General Section of the African Court will rely on in performing its appellate jurisdiction. Article 31 of the Protocol lays out the applicable law governing the functions of the African Court in general. These are: the Constitutive Act of the African Union; international treaties of a general or specialized nature; international custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law; general principles of law recognized universally or by African States; judicial decisions and writings of the ‘most highly qualified publicists of various nations,’ as well as regulations, directives and decisions of the African Union as a subsidiary means of determining the rules of law; and ‘any other law relevant to the determination of the case.’Footnote 38

Although Article 31 of the Protocol does not specify the sources of law applicable in the exercise of the Court’s appellate review of AUAT decisions, the specific sources of law applicable in international administrative law are well covered under the provision for ‘any other law relevant to the determination of the case’ (Article 31(1)(f)). As Amerasinghe observes, ‘[i]n seeking the sources of employment law (international administrative law) it would be too naïve and simple to draw analogies from the sources of public international law.’Footnote 39 Indeed, ‘[i]t is tempting to assume that the sources of international administrative law may easily be derived, at least by analogy, from the sources of public international law, because international administrative law is a part of public international law.’Footnote 40

Few statutes of international administrative tribunals expressly state the applicable law. Three exceptions can be found in the statutes of the Commonwealth Secretariat Arbitral Tribunal (CSAT), the African Development Bank Administrative Tribunal (AfDBAT) and the Administrative Tribunal of the Organization of American States (OASAT).

Article XII(1) of the Statute of the CSAT provides that the CSAT shall be ‘bound by the principles of international administrative law which shall apply to the exclusion of the national laws of individual member countries.’Footnote 41 The Statute further provides that in other cases the CSAT ‘shall apply the law specified in the contract. Failing that, it shall apply the law most closely connected with the contract in question.’ Article V(1) of the Statute of the AfDBAT provides that ‘the Tribunal shall apply the internal rules and regulations of the Bank, and generally recognized principles of international administrative law concerning the resolution of employment disputes of staff in international organizations.’Footnote 42

The Statute of the OASAT makes clear that ‘[f]or the adjudication of any disputes involving the personnel of the General Secretariat, the internal legislation of the Organization shall take precedence over general principles of labour law and the laws of any member State; and, within that internal legislation, the Charter is the instrument of the highest legal order, followed by the resolutions of the General Assembly, and then by the resolutions of the Permanent Council, and finally by the norms adopted by the other organs under the Charter - each acting within its respective sphere of competence.’Footnote 43

In performing its appellate review of decisions of the AUAT, the applicable primary sources of law would be the AU Staff Regulations and Rules and the contracts, conditions and terms of appointment of the staff member submitting an appeal before the African Court. As the WBAT clarified in its first case, though the employment contract may be the sine qua non between the staff member and the international organization, ‘it remains no more than one of a number of elements which collectively establish the ensemble of conditions of employment operative between the [organization] and its staff members.’Footnote 44

Further sources of law could include Articles of Agreement, By-laws, administrative circulars, manuals and statements issued by management of the African Union depending on the circumstances of the case. Rule 78.3 of the 2010 Staff Regulations and RulesFootnote 45 enumerates these administrative documents, which could be applicable depending on the case under review:

(a) Administrative Circulars;

(b) Administrative Procedure Manual;

(c) Code of Ethics;

(d) Policy on Sexual Harassment;

(e) Information, Communication and Technology Policy;

(f) Medical Assistance Plan;

(g) African Union Travel Policy;

(h) Orientation Training Manual;

(i) Performance Appraisal Policy;

(j) Policy on Education Allowance;

(k) Policy on the Management of HIV/AIDS at the Workplace;

(l) Procurement Manual;

(m) Pension Policy;

(n) Safety and Security Guideline;

(o) Training Policy; and

(p) Recruitment, Advancement, Upgrading and Promotion Policy.

The practice of the organization may also become part of the conditions of employment in certain circumstances. General principles of law would include those applicable in the law of contracts, and other jurisprudence developed by other administrative courts and tribunals. Finally, it is worth noting the overlap, in some areas, between human rights and international administrative law. Where necessary, the Court may rely on applicable human rights treaties as well as established human rights principles.

D. Procedural Matters

This section briefly explores a limited number of observations on procedural matters. Some procedural matters not addressed here include the need to extend the definition of eligible persons to include former staff members who may be challenging decisions concerning their pension, as well as beneficiaries of deceased staff members.

1. Binding Force and the Availability of Enforcement Measures

Article 46(2) of the Court’s Statute as amended by the Amendments Protocol, provides that ‘[s]ubject to the provisions of Article 18 (as amended) and paragraph 3 of Article 41 of the Statute, the judgment of the Court is final’.Footnote 46 Article 46 further includes provisions on enforcement measures which, while evidently drafted with inter-state disputes in mind, could be equally relied upon by appellants to ensure full compliance by the African Union with remedies awarded such as re-instatement in the event of termination of employment, or compensation.

According to Article 46(4) where a party has failed to comply with a judgment, the ‘Court shall refer the matter to the Assembly, which shall decide upon measures to be taken to give effect to that judgment.’ This may be useful to rely upon in the event that the organization is reluctant to implement the awards and remedies issued, and it would be interesting to observe whether an appellant is able to rely on this provision in practice.

2. Remedies and Compensation

Article 45 of the Protocol offers a general basis on which to determine the appropriate compensation. Article 45 provides that:Footnote 47

Without prejudice to its competence to rule on issues of compensation at the request of a party by virtue of paragraph 1(h), of Article 28 of the present Statute, the Court may, if it considers that there was a violation of a human or peoples’ right, order any appropriate measures in order to remedy the situation, including granting fair compensation.

Other remedies which are available in international administrative law include rescission of the contested decision, specific performance, restitution and moral damages. In light of the fact that the African Court will review the decision of the AUAT, and not the administrative or disciplinary decision of the organization, applicable remedies could also include vacation of the AUAT’s decision, affirming, reversing, modifying the findings of the AUAT, or remanding the decision back to the AUAT for additional finding of fact. The latter, which is a remedy available in the UNAT Statute, may be difficult to apply since the AUAT Judges sit together in plenary.Footnote 48

3. Non-Suspensive Effect of AUAT Decisions and the Availability of Provisional Measures

It is observed that there are two provisions which would need to be reconciled on the matter of non-suspensive effect and availability of provisional measures. The first is Rule 62.4 of the AU Staff Regulations and Rules which provides that ‘[t]he filing of an appeal with the African Court of Justice and Human Rights shall not have the effect of suspending the execution of the Administrative Tribunal decision being contested.’ The second provision, contained in the Protocol, is Article 35 on provisional measures. Article 35(1) permits the Court, ‘on its own motion or on application by the parties, to indicate, if it considers that circumstances so require, any provisional measures which ought to be taken to preserve the respective rights of the parties.’

With the exception of the UN internal justice system,Footnote 49 the non-suspensive effect of administrative decisions is standard in administrative law jurisprudence. However, it is equally accepted that a staff member may request interim or provisional measures to suspend a decision where it is demonstrated that the execution of that decision would cause irreparable hardship. For instance, Rule 13(1) of the Rules of the WBAT provides that though the filing of an application would not have suspensive effect on the contested decision, the applicant may submit ‘a request to suspend the contested decision until the Tribunal renders its judgment in the case’. Rule 13(3) further adds that ‘[t]he Tribunal, or when the Tribunal is not in session, the President of the Tribunal may grant such a request in a case in which the execution of the decision is shown to be highly likely to result in grave hardship to the applicant that cannot otherwise be redressed.’Footnote 50

Article VI (4) of the Statute of the Administrative Tribunal of the International Monetary Fund also provides that the filing of an application shall not have the effect of suspending the implementation of the contested decision. However, its accompanying Commentary notes that:Footnote 51

Section 4 follows the principle applicable to other tribunals that the filing of an application does not stay the effectiveness of the decision being challenged. This is considered necessary for the efficient operation of the organization, so that the pendency of a case would not disrupt day-to-day administration or the effectiveness of disciplinary measures, including removal from staff in termination cases. This rule is also consistent with the principle, strictly applied in the employment context, that an aggrieved employee will not be granted a preliminary injunction unless he would suffer irreparable injury without the injunction. […] [I]t is difficult to envisage a situation in which the harm to an applicant, in the absence of interim measures, would be “irreparable,” as that concept has been construed by the courts. Nevertheless, the statute would not preclude the tribunal from ordering such measures if warranted by the circumstances of a particular case.

It would be useful for the Court to make clear, in its Rules, the conditions upon which a request for provisional measures may be granted in appeals by employees of the AU, thereby reconciling the above-mentioned provisions and ensuring consistency with international administrative law.

3. Conclusion

The availability of the African Court as a viable extension of the justice mechanisms for staff members of the African Union depends on the politics of when, and if, the Protocol enters into force, and the African Court becomes operational. Nevertheless, the extension of the Court’s jurisdiction to matters of international administrative law provides an opportunity for a more robust system for the resolution of such disputes, given the immunities enjoyed by the African Union. The Court has the potential to greatly impact and develop the law of international organizations, given its unique position as the region’s highest court and its mandate to interpret fundamental principles of international law.

As a body conducting appellate reviews of decisions of the AUAT, it is imperative that the Court ensures equality of access and protects the due process rights of each party. Recommendations noted above include amendment of Article 29(1)(c) to include the African Commission as an entity eligible to appeal decisions of the AUAT. To ensure consistency with the jurisprudence and practice of international administrative tribunals, it is also recommended that the adopted Rules of Procedure: (a) clarify the scope of the Court’s appellate review; and (b) consolidate provisions on the non-suspensive effect of AUAT decisions and the availability of provisional measures.