Epidemics do not just happen. They are not random events. They have histories.

Cholera is only a different shade on the canvas of ill-health. The cause of cholera is not to be found in biology, but in poverty. Inadequate and non-existent sanitation and the lack of piped clean water are the immediate causes of the spread of the disease. But the roots of cholera lie in an unequal distribution of resources – too much for some, very little or next to nothing for others.

In October 2016, fully eight years after the cholera catastrophe of 2008, the Zimbabwean government issued an ominous alert about a potential cholera outbreak in multiple areas throughout the country. The Minister of the Environment, Oppah Muchinguri-Kashiri, held a press conference in which she told journalists that government was debating whether to declare ‘the whole country a water shortage area’ (cited in News24 2016). The announcement came less than twenty-four hours after the Minister of Health, David Parirenyatwa, publicly discussed the high risks of waterborne diseases in the event of flash floods – a common experience during Zimbabwe’s rainy season. Muchinguri-Kashiri went on to add:

Something has gone wrong with us Zimbabweans. Zimbabweans are living dangerously. We cannot live luxuriously like this and forget that we are humans … Murungu anga akaipa asi aive noruzivo nezvemagariro emativi mana ake (The white person was cruel, but had vast knowledge on how to live in a community and care for its surroundings).

According to the minister, Zimbabwe had become so filthy that even the Rhodesian regime, cruel and authoritarian as it was, had managed the urban environment more hygienically and knowledgeably than contemporary Zimbabweans. She bemoaned a lack of general cleanliness throughout the whole country saying that ‘Zimbabwe had become one of the dirtiest countries in Southern Africa.’ As part of a cycle of self-destruction, Muchinguri-Kashiri said, Zimbabweans had become ‘reckless and careless about their environment’, rural communities cut down trees in farmlands randomly and without due regard for why the trees might be needed, urban dwellers pollute the environment with abandon, and, for more than a decade, raw sewage flowed through city streets while people inexplicably expected to be immune from disease. The prospect of cholera was invoked as a reminder of the deadly consequences of filth and recklessness, of the failure of people to maintain their surrounding environment. Muchinguri-Kashiri’s statements gesture toward history in an ambivalent way that captures, on one hand, a sense of inherited social and environmental order from colonial rule and, on the other, a rupture in historical consciousness in which a collective sense of order and responsibility has given way to self-centredness, short-termism and disregard. Hers is a narrative of irresponsible citizenship and individual blame that belies the extended, multi-scalar political-economic factors that produce cholera epidemics.

A growing body of literature uncovers and dissects the deep historical complexity of differing, overlapping and entangled African urban imaginaries, aspirations to modernity, and notions of respectability, cutting across the divisions of class, age, gender, religion and political allegiance across urban Zimbabwe (see Raftopoulos and Yoshikuni Reference Raftopoulos, Yoshikuni, Raftopoulos and Yoshikuni1999; Ranger Reference Ranger2007; Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007; Fontein Reference Fontein2009; Dorman Reference Dorman2015). Ideas about what defines order and what constitutes filth have long been shaped by the politics of governing the city and the strategies that different authorities have used over time to deliver urban services, to regulate hygiene and waste management, to manage public housing and transport, and to police social conduct and punish deviance. These ideas give Muchinguri-Kashiri’s remarks some context, but they must also be explored in relation to the material factors that underpin urban order. Infrastructure plays a central role in this regard. It is significant that Harare’s hydraulic infrastructure, for instance, was first established and extended during its time as a colonial city. The production of water systems in the city was designed to discriminate between white settlers accorded full membership to the polity and Africans for whom the promises of citizenship were deferred or denied (see Anand Reference Anand2017). The infrastructures that were rapidly produced, extended and renovated from late 1800s through much of the early twentieth century – roads, sanitary infrastructures, marketplaces, nascent industries and housing provision – enabled a series of constitutive, though contested, divisions necessary for the operation of racial segregation in everyday life. The social differences enabled by urban infrastructures were reproduced by the accreted laws, policies and techniques for governing the city.

The making of the 2008 cholera outbreak is bound up with the history of Harare’s infrastructure and the politics of creating urban order. In this chapter, I situate the cholera outbreak in this historical perspective. I emphasise the temporal depth of the processes that led to its occurrence. I do so first by delineating the structural factors that predisposed Harare’s townships to a diarrhoeal disease outbreak. Central to my argument is the claim that historically produced segregation in the name of creating urban order resulted in profound social inequality and laid down the underlying physical conditions in the high-density townships – namely poor sanitation facilities, inadequate clean water provision and other public amenities, and overcrowded housing – for the potential spread of an epidemic in these parts of the city. Such conditions can be traced as far back as the late nineteenth century when Harare was founded as a colonial administrative centre. Second, I show how these conditions have persisted through the twentieth century and were never adequately rectified by the post-colonial government, itself pursuing a contradictory and contested vision of urban order. Finally, I look more closely at shifts in Harare’s urban politics during the country’s post-2000 political and economic meltdown, to set the scene of ‘the crisis’ which precipitated the cholera outbreak (see Hammar, Raftopoulos and Jensen Reference Hammar, Raftopoulos and Jensen2003; Raftopoulos Reference Raftopoulos, Raftopoulos and Mlambo2009; J. L. Jones Reference Jones2010b; Alexander and McGregor Reference Alexander and McGregor2013; Dorman Reference Dorman2016).

Unlike the chapters that follow, which all concentrate on a very narrow timeframe pivoted around the cholera outbreak itself, this chapter takes a broader view. As such, I will touch on critical events and periods in Zimbabwe’s twentieth-century history, about which there is intense scholarly debate, though I do not weigh in on these arguments. This chapter insists that a long-range view offers a crucial explanatory dimension – specifically the historical politics of urban order and infrastructure – to the events, understandings, actions and structures that defined the cholera outbreak. I must stress that I am not suggesting that the cholera outbreak was in any way inevitable, quite the opposite: by providing this historical context, I am able to show in these first two chapters of the book both the path dependency and the contingency that led to the epidemic at such an epic scale in 2008 rather than at any other time in history.

Establishing Urban Order: The City and the Colonial Frontier

At his inaugural lecture when taking a chair in the Department of History at the University of Zimbabwe, Professor David Beach (Reference Beach1999: 14) acerbically quipped that, ‘Unfortunately, when it comes to long-term planning Homo sapiens zimbabweansis is not significantly different from H. sapiens rhodesiensis. Indeed, the two are far more alike than many would care to concede.’ Beach proceeded to note that nowhere was this clearer than in the siting of what was then Salisbury, the capital city of Southern Rhodesia, by the colonial state. As he put it (Beach Reference Beach1999: 14),

Even urban planning was atrociously bad. Leaving aside the lack of thinking that left only a 45° segment of Salisbury for the African population; the very siting of the city was and is incompetent. It is well known that in 1890 the site was chosen at very short notice but what is not generally known is that in 1891 the Company (British South Africa Company) did think of re-siting it, considering Norton, Mvurwi, Darwendale and even Rusape. The proposal to move the town was rejected, allegedly because the other sites were a few metres lower and thus less healthy, but actually because six brick buildings had already been put up, and the property developers did not want to lose their investments. Consequently, the town remained where the city is, upstream of its main water supply, and thus we are condemned to drink our own recycled waste!

Beach (Reference Beach1999: 14) pointed out that on the eve of the new millennium, the population in Zimbabwean cities, such as Harare, was potentially increasing ‘at a rate faster than the national average [and that] they are going to run short of water relatively quickly’. Muchaparara Musemwa (Reference Musemwa, Chiumbu and Musemwa2012: 4) traces the post-2000 urban water crisis that induced the 2008 cholera outbreak back to Harare’s ‘post-colonial water shortages and sanitation problems and the monumental errors of judgement by early colonial planners’.

Urban settlements in Zimbabwe were initially established as administrative and political structures for colonial rule. Early forms of urban structures were built on the bases of military settlements, camps and forts (for example, Fort Tuli, Fort Victoria, Fort Charter and Fort Salisbury) (Raftopoulos and Yoshikuni Reference Raftopoulos, Yoshikuni, Raftopoulos and Yoshikuni1999). The first settlers of Salisbury constituted the so-called Pioneer Column. They had travelled from South Africa as part of the imperialist conquest of Cecil John Rhodes, the British mining magnate and governor of the Cape Colony. Rhodes’s British South Africa Company endeavoured to find the ‘Second Rand’ – a new iteration of the Witwatersrand gold rush that led to the establishment of Johannesburg – from the ancient gold mines in Mashonaland. Staking their hopes on the possibility that a greater Witwatersrand lay under the sub-soil of Mashonaland, the township of Salisbury was initially planned as a frontier town for the habitation of 25,000 people with a ‘commonage’ of more than 20,000 acres encircling it (Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007: 10). The frontier town was to be orientated toward racial separateness and economic exploitation. For Julie Seirlis, this movement demonstrated the militancy of Rhodesia’s colonial expansion and its racial configuration of space:

The topography of white spaces as a fortress, a citadel, a laager, is a profound expression of colonialism’s militancy and a concrete expression of the politics of control and domination. It also emphasises the neurosis and paranoia built into the realisation of that control and domination because the fortress suggests a need for protection against a hostile environment, an attitude of defensiveness from a perceived or actual state of siege.

The drive for segregation in the frontier town was first entertained as a formal policy in 1892–93. Tsuneo Yoshikuni (Reference Yoshikuni2007: 28) recounts this history. He notes that the sanitary board considered removing ‘all coloured people’, including the Asians, to ‘separate portions of the town’. In part, this was in response to a stream of Asian immigrants into Rhodesia’s nascent urban areas. The idea was not a practical policy but a partisan expression of the ideal of ‘total segregation’. By 1902, the Salisbury council adopted a similar position. The press mildly cautioned against this position, arguing that ‘its feasibility or otherwise has yet to be determined’. Yet, in spite of the apparent impracticability of such a policy, the press proceeded to acclaim the proposal as a ‘timely action’ being ‘in the best interests of the Municipality’. The salience of the council’s position at this time was not the principle of total segregation itself, but the ideas invoked in its justification (Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007). Central to these were claims of ‘urban problems’ such as the ‘Black Peril’ (the fear that black men would sexually prey upon white women) (McCulloch Reference McCulloch2000) and the alleged public health problems, the ‘sanitation syndrome’ discussed below, caused by the presence of Africans in the city.

In this respect, the push for segregation was part of a wider trend in the region, which was just undergoing the process of capitalist, industrial urbanisation. In South Africa, segregated townships, called locations, were gaining official currency as a panacea for all manner of urban racial problems. For example, when the bubonic plague broke out in the port towns of the Cape Colony in 1901, serious attempts were made at expelling African workers from inner cities. During this time, urban race relations became widely conceived of and dealt with in the imagery of infection and epidemic disease. Maynard Swanson (Reference Swanson1977: 410) calls this the ‘sanitation syndrome’ – the equation of black urban settlement, labour and living conditions with threats to public health and security – and he argues that it ‘became fixed in the official mind, buttressed a desire to achieve positive social controls, and confirmed or rationalized white race prejudice with a popular imagery of medical menace’. This is amply illustrated by the racially selective application of quarantine regulations and disease control measures in Port Elizabeth during the bubonic plague epidemic of the early 1900s:

Blacks were especially resentful at the discriminatory application of the plague quarantine regulations. Officials called it ‘class discrimination’, but their attitudes were clearly racial and Africans complained bitterly of maltreatment and abuse on grounds of colour. The houses of blacks had been quarantined; those of neighbouring whites had not. The possessions of blacks had been burned; the goods, the stores, and the warehouses where they worked and contracted the plague had not been touched, because those belonged to whites.

In essence, according to Swanson (Reference Swanson1977: 387), the sanitation syndrome was a ‘major strand in the creation of urban apartheid’. The Salisbury councillors were conversant with these developments ‘down south’ and sent letters to municipalities in the Cape Colony requesting information on urban locations (Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007). The Cape government claimed to have relieved the city of ‘its burden of uncivilized, low-paid, slum-bound, disease-ridden black labourers’ (Swanson Reference Swanson1977: 394). This was, of course, merely a racist representation of Africans with no bearing on the actual epidemiology of infectious disease. Segregation was not driven by rational calculation, nor was it a universally accepted policy among the Rhodesians. This caused tension and disputes within and between government, industry and the communities, most notably between the settlers and the British South Africa Company, which ruled Southern Rhodesia from occupation in 1890–1923. The settlers accused the company of putting its own commercial interests ahead of settler social, political and economic preferences, which for many included total racial segregation (Mlambo Reference Mlambo2014). To an important extent, it seems, Rhodesians were divided about how to provide for the mutual access of black labourers and white employers in the incipient industrial age without having to pay the heavy social costs of urbanisation or losing the dominance of Europeans over Africans.

The central state clashed with the Salisbury councillors over the extent of segregation in urban areas. The former downplayed the invective rhetoric of Black Peril or the ‘sanitation syndrome’ and instead insisted on greater liberties in housing and movement for African ‘free’ residents, that is, those Africans who were not ‘accommodated’ at their white employers’ private residence (Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007). To streamline the legislation regarding the locations, the Rhodesian government introduced the Native Urban Locations Ordinance (No. 4 of 1906) prohibiting African ‘free’ residence in Salisbury with full effect from 1 May 1908, and by the end of April 1908 the town police reported: ‘all natives in the Township and on the Commonage, occupying premises, not used by their masters, have been warned they will have to remove to the Location on the 1st of May’ (quoted in Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007: 19).

During this same period, circa 1908, Salisbury underwent a ‘municipal revolution’ (Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007: 11). With the failure to discover new reserves of gold in Mashonaland, the Rhodesian settlers shifted their focus to ‘practical colonisation’: extension of railways and roads; commencement of settler agriculture and land acquisition; establishment of banks, mercantile houses and workshops; introduction of new transport facilities; institution of postal and other administrative services; and development of primary industries in areas like Hartley, Gatooma, Lomagundi and Marandellas (Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007). The stimulation of business and economic growth fostered major civic improvements, perhaps the most outstanding of which was the introduction in 1913 of piped water and electricity supplies. In the process, Salisbury started to shed its hitherto militaristic outlook and assumed ‘the more genteel trappings of a white middle-class paradise’ (Seirlis Reference Seirlis2004: 413). As settler colonialism took firmer root, Salisbury transformed for its white residents from a mere ‘commercial and administrative centre’ to ‘a countrified suburbia where whites could live in the manner of landed gentry on mini-estates complete with rose gardens and servants’ (Seirlis Reference Seirlis2004: 414).

In October 1922, Britain held a referendum for Rhodesian settlers to determine their future either as part of the Union of South Africa, since the country was still formally ruled by the British South African Company, or as a self-governing entity. A majority vote passed in favour of the latter, making Southern Rhodesia a self-governing territory with a high degree of autonomy even though Britain retained control over foreign policy as well as the right to veto legislation seen as detrimental to Africans (Mlambo Reference Mlambo2014). Successive self-government regimes entrenched segregation in the country through various measures to ensure African subservience (Mlambo Reference Mlambo2014). The logic that ultimately prevailed – for the colonial state and the constituent classes of small businessmen, the railway establishment, white workers and city councils – was that urban space was a temporary place of work for Africans and was to be occupied so long as labour functions were being performed and at as little cost as possible to the central state and the city council. The authentic African locus of home and family in the settler colonial imagination was then recast as the rural area, the site of ‘traditional’ structures and control (Phiminister Reference Phiminister1988; Raftopoulos and Yoshikuni Reference Raftopoulos, Yoshikuni, Raftopoulos and Yoshikuni1999; Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007; Ndlovu-Gatsheni Reference Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Raftopoulos and Mlambo2009b; Musemwa Reference Musemwa, Chiumbu and Musemwa2012).

To take a panoramic view of the town, the growth of Salisbury generated a hierarchy of urban space. On a virtual sliding scale of residential prestige, the town transmogrified from the homogenous north-east, with its elegant, colonial-style bungalows and cottages, down towards the polyglot south-west, where an assorted collection of brothels, boarding houses, Indian shops, a Jewish synagogue, ‘native locations’, and the dwellings and stores of ‘pioneers’ were to be found (Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007). The enforcement of segregation to protect the emerging ‘white sanctuary’ spawned a legislative labyrinth to control African movement into and within the city. For example, ‘pass laws’ were officially introduced under the Native Registration Act in 1936 to limit the African population’s access to urban spaces while other laws imposed curfews on Africans; prohibited Africans from owning land designated as ‘European’; and restricted African access to housing, typically provided for single male occupancy, thereby stemming the migration of rural families into the city (Phiminister Reference Phiminister1988; Sapire and Beall Reference Sapire and Beall1995; Raftopoulos and Yoshikuni Reference Raftopoulos, Yoshikuni, Raftopoulos and Yoshikuni1999; Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007; Ndlovu-Gatsheni Reference Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Raftopoulos and Mlambo2009b; Musemwa Reference Musemwa, Chiumbu and Musemwa2012).

Yoshikuni (Reference Yoshikuni2007) argues that the establishment of the urban location to house Africans must be seen primarily in the light of growing citizen pressure, especially emanating from working-class whites in the Kopje area of Salisbury, and not the ‘sanitation syndrome’. He insists that there is little evidence to support the ‘sanitation theory’ often conveniently deployed by colonial officials to motivate their segregationist policy, and advanced by scholars like Lewis Gann and Peter Duignan (Reference Gann, Duignan, Gann and Duignan1970: 138–39), who argued that in Salisbury’s early days ‘there was no segregation … In the 1900s, however, disease struck the shantytowns and convinced the white citizens that something must be done. They hastily cleared the infected area and shifted the Africans into a “location”.’ However, neither serious epidemic nor massive removals occurred at any point in the first decade of the twentieth century. The location policy focussed on clearing the town and was presented to white citizens as a solution to an imagined ‘community crisis’. Underpinning the government’s adoption and enforcement of racial segregation was a perceived rising threat of African economic competition, which was heightened during the austere economic times heralded by the Great Depression (Mlambo Reference Mlambo2014).

The leading exponent of racial segregation was Godfrey Huggins, leader of the Reform Party, who assumed the role of prime minister of Southern Rhodesia from 1934 to 1953. Huggins advocated a ‘Two Pyramid Policy’, from 1938 onwards, of separate development for the Europeans and Africans. In his own words,

The European in this country can be likened to an island of white in a sea of black, with the artisan and the tradesman forming the shores and the professional classes the highlands in the centre. Is the native to be allowed to erode away shores and gradually attack the highlands? To permit this would mean that the leaven of civilisation would be removed from the country, and the black man would inevitably revert to a barbarism worse than ever before …. Rightly or wrongly, the white man is in Africa and now, if only for the sake of the black man, he must remain there. The high standard of civilisation cannot be allowed to succumb.

The patterns and trajectory of urbanisation and segregated settlement were haphazard and disorganised despite efforts to generate a pristine ‘white city’ with a steady labour supply. These conflicts and dissonances are well documented by a range of scholars who have looked at the myriad ways in which Africans defied the intentions of discriminatory legislation and asserted their public presence within the city (see Raftopoulos and Yoshikuni Reference Raftopoulos, Yoshikuni, Raftopoulos and Yoshikuni1999 for a summary).

Housing control was envisioned as a fundamental means, along with a pass and night curfew system, to control the behaviour and movement of the African worker. The colonial state and city council worked to confine African residence to either the employer-controlled servants’ quarters or a municipality-supervised location. The housing estates provided at the latter were bitterly unpopular among Africans. Municipal involvement in African housing was the product of a demand for exclusion and the policy was characterised by ‘utter disregard for the quality of tenants’ lives’ (Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007: 41). Additionally, Yoshikuni argues, the council viewed the production of African housing in terms of revenue and, combined with housing controls, this enabled the council to charge a monopoly rate leading to a high rate of rent appropriation.

Another major strand of the council’s involvement in the location was its preoccupation with social control. Further to the elaborate regulations governing the movement of Africans, the location was also placed under heavy police rule such that the townships were often enclosed within a barbed-wire fence and kept under surveillance. The high concentration of policing staff in very small locations augmented pressure on rents. Most importantly, the location was ‘a bleak place’, as Yoshikuni describes:

Inside there existed no amenities, no schools, no shops, no churches and no clinics – only the large municipal beer canteen. In 1920 a neighbourhood of 250 huts shared just one borehole and three communal latrines, without a single ablution facility for them.

At a general level, such regulations and measures of social control laid the foundations for the trajectory of housing in the townships.

Over time, overcrowding and inconsistency in the availability and quality of service provision have typified the townships. Another long-standing, major concern in the townships has been access to hygiene and sanitation facilities. From its very founding, the difficulty of acquiring sufficient supplies of water has persisted in the course of Harare’s colonial and post-colonial history. In the late nineteenth century, prior to the ‘municipal revolution’, the colonial settlers sourced their potable water from springs, rooftops, individual wells and boreholes. And yet even with the provisions for piped water in Salisbury from about 1913, an amalgam of factors – such as climate; relief; geology and location on the central watershed (Tomlinson and Wurzel Reference Tomlinson, Wurzel, Kay and Smout1977 note the absence of sedimentary formations that could provide large aquifers in the vicinity of Harare); the long dry season with about eight months per year of minimum stream-flow; and the seasonal high rates of evapo-transpiration (Davies Reference Davies1986) – all curtailed the city council’s ability to secure reliable access to water as the city expanded.

Limitations on the water supply became a serious bone of contention in city council politics whenever the issue of latrine facilities for Africans was raised. In the early years of the colonial city, most business firms and private households failed to provide sanitary conveniences for their African workers. To address this, the sanitary board built a few ‘native latrines’ at street corners, but such facilities were totally inadequate for the needs of the African population. In 1895, the Township Sanitary Regulations (No. 109 of 1895) were introduced to compel every employer in Salisbury to provide latrines for servants. But the regulations had little influence on practice. Over time, as Salisbury gradually grew into an urban agglomeration, fears mounted about a potential infectious disease outbreak, such as typhoid or smallpox. Medical officials therefore repeatedly warned of the dangers of the dearth of sanitary facilities for the majority of the population, especially at a time when the town depended on wells for its water supply, but such alerts exerted minimal influence on policy decisions. Heated debates erupted at the town house but yielded no result, with the municipality often concluding that the cost of erecting ‘native latrines’ was too much for ratepayers (Yoshikuni Reference Yoshikuni2007; Musemwa Reference Musemwa, Chiumbu and Musemwa2012).

The piped water distribution to the townships closely mapped onto the segregationist impulse and the prevailing assumption about African impermanence in urban areas. For the most part, the locations only received clean piped water, toilets and sewers as a fringe benefit of sanitary and water improvements occurring elsewhere in the city. Important predisposing, and mutually reinforcing, factors for the cholera outbreak thus obtained during this period. In 1953, Harare’s current water supply system was laid down in parallel with the sewage disposal system, and both were situated in the same water catchment zone (Musemwa Reference Musemwa2010). Additionally, the spatial pattern of topographical elevation in the city followed the socio-economic hierarchy of urban settlement whereby the low-density, affluent, white parts of the city were situated at higher altitude than the high-density, poor, African townships. Most of Harare was therefore located upstream of its main water supply. As such, the reticulation system depended on a sophisticated and elaborate hydraulic infrastructure of pumps and chemical treatment to deliver clean, potable water against the gravitational pressure gradient.Footnote 1 As a contingency plan against an engineering failure of the reticulation system, residents of the affluent areas of Harare had installed private boreholes to access groundwater directly and/or they were able to buy water from private sources that obtained water from outside the city. In the high-density townships, boreholes were extremely limited. Instead people dug shallow wells as an additional or alternative water source to the council water supply (Tomlinson and Wurzel Reference Tomlinson, Wurzel, Kay and Smout1977).

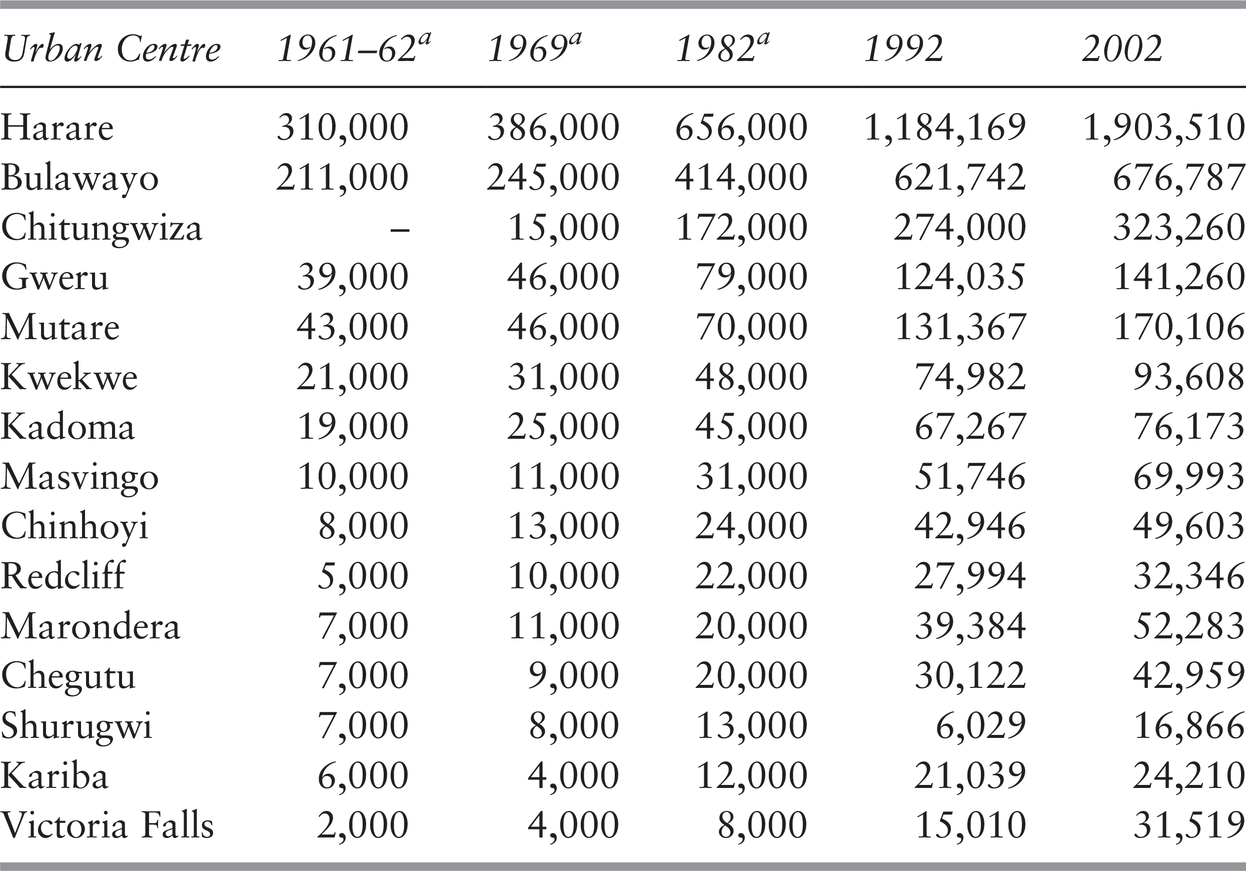

Given these observations, Musemwa (Reference Musemwa, Chiumbu and Musemwa2012: 17) tentatively posits that ‘with meagre sanitation amenities and rudimentary water technologies, the urban planners and administrators were setting up the townships as future sources of disease.’ One key reason he offers for the lag time between the establishment of the townships and a major outbreak of diarrhoeal disease is Harare’s relatively low rates of urbanisation for much of its history because of the legislative control of African residence in the city under colonial rule. The percentage of urban-based African populations before 1978 had remained almost constant over the preceding seventeen years. However, as the liberation struggle for independence against colonial rule intensified in the 1970s, people in rural areas sought refuge in urban areas, resulting in a marked rise in the population of cities by 1979. With limited housing stock for Africans in the capital, overcrowding became inevitable in the locations. Salisbury’s population expanded dramatically from 280,000 in 1969 to 633,000 by January 1980 (Patel Reference Patel and Schatzberg1984). Consequently, informal settlements proliferated within the townships on the periphery of the city. This process, described by Musemwa (Reference Musemwa, Chiumbu and Musemwa2012: 18) as ‘galloping urbanism‘ (see Table 1.1) exposed ‘the insufficiency of the government’s housing policy to satisfy the requirements of the urban poor for shelter and other attendant elementary amenities such as water, sewage, electricity and roads’.

Table 1.1 Zimbabwe’s urbanisation trends, 1961–2002

| Urban Centre | 1961–62a | 1969a | 1982a | 1992 | 2002 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harare | 310,000 | 386,000 | 656,000 | 1,184,169 | 1,903,510 |

| Bulawayo | 211,000 | 245,000 | 414,000 | 621,742 | 676,787 |

| Chitungwiza | – | 15,000 | 172,000 | 274,000 | 323,260 |

| Gweru | 39,000 | 46,000 | 79,000 | 124,035 | 141,260 |

| Mutare | 43,000 | 46,000 | 70,000 | 131,367 | 170,106 |

| Kwekwe | 21,000 | 31,000 | 48,000 | 74,982 | 93,608 |

| Kadoma | 19,000 | 25,000 | 45,000 | 67,267 | 76,173 |

| Masvingo | 10,000 | 11,000 | 31,000 | 51,746 | 69,993 |

| Chinhoyi | 8,000 | 13,000 | 24,000 | 42,946 | 49,603 |

| Redcliff | 5,000 | 10,000 | 22,000 | 27,994 | 32,346 |

| Marondera | 7,000 | 11,000 | 20,000 | 39,384 | 52,283 |

| Chegutu | 7,000 | 9,000 | 20,000 | 30,122 | 42,959 |

| Shurugwi | 7,000 | 8,000 | 13,000 | 6,029 | 16,866 |

| Kariba | 6,000 | 4,000 | 12,000 | 21,039 | 24,210 |

| Victoria Falls | 2,000 | 4,000 | 8,000 | 15,010 | 31,519 |

a Estimates

Transforming Urban Order: The City and ‘Modernising Development’

The liberation struggle for independence by African nationalist forces against Rhodesian rule lasted fifteen years, from the mid-1960s until the end of 1979. A bloody and destructive struggle, the war also saw the Rhodesian army using biological agents against the liberation movements. The techniques the Rhodesian forces used included poisoning wells; spreading cholera; infecting clothing used by insurgents; and killing cattle with anthrax to deplete insurgent food supplies, which resulted in the world’s largest recorded anthrax outbreak (Martinez Reference Martinez2002). Rhodesia’s Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) and its special-forces regiment, the Selous Scouts, disseminated cholera in Mozambique and along the border to debilitate incursions from the eastern front. However, the CIO feared that the use of cholera could backfire and spread into Rhodesia uncontrolled and infect government army forces operating in the field. The use of cholera as a weapon was eventually discontinued because the agent was thought to dissipate too quickly to provide any lasting tactical advantage. Nevertheless, the use of cholera as a weapon in the liberation struggle would return to the fore of political consciousness and discourse over two decades later as I shall discuss in Chapter 3.

The conflict came to an end with the Lancaster House Conference in 1979 where an independence constitution, arrangements for the post-independence period and a cease-fire agreement were all put in place. Under these new arrangements, the country held elections in February 1980. The Zimbabwe African National Union, led by Robert Mugabe, now renamed ZANU-Patriotic Front or ZANU(PF), won an overwhelming majority with 57 seats in a parliament of 100 members. The other major nationalist movement turned political party, the Zimbabwe African Patriotic Union (ZAPU), garnered twenty seats, the United African National Council (UANC) claimed three seats and the Rhodesian Front took all twenty seats reserved for white Zimbabweans. The country formally marked its independence on 18 April 1980.

‘As the sound of the celebrations died away after 18 April 1980, the sound of picks and shovels became audible; the development of Zimbabwe had begun,’ wrote Nicholas Ndebele (cited in Auret Reference Auret1990: v, emphasis added), a former director of the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (CCJP) in Zimbabwe, when recalling the first decade of the country’s independence from colonial rule. For the victors of the war, it was a period of hope and optimism as well as one of fierce ambition as ZANU(PF) endeavoured to transform the country and consolidate its political hegemony over its former colonial rulers and nationalist rivals. In concrete terms, the incoming government inherited an advanced manufacturing sector, sophisticated infrastructure, a relatively large network of banks and a highly technocratic, centralised and powerful bureaucratic state apparatus from its Rhodesian predecessor. As noted in the Introduction, the new ruling party, ZANU(PF), was quick to put this powerful machine to use in the service of ‘modernising development’ (Alexander Reference Alexander, Mustapha and Whitfield2010). Though technocratic and bureaucratic to a fault (Alexander Reference Alexander, Mustapha and Whitfield2010), the new government was able to deliver. Throughout the 1980s, the government expanded access to healthcare, education and sanitation. It initiated a large land resettlement programme in rural areas. The central legitimating claim of the new government was its promise to bring about development and modernisation (Karekwaivanene Reference Karekwaivanene2012). Crucially, the gains made in this period were not only material: they signalled the new government’s aspirations to modernity, its capacity to deliver public goods as a source of political legitimacy, and its commitment to reversing some of the entrenched racial inequalities of the colonial period. Importantly, as Alexander and McGregor (Reference Alexander and McGregor2013) write, the government’s capacity to deliver modernisation and development was facilitated, to a critical extent, by the commitment among civil servants to a professional ethic. This ethic was central to ZANU(PF)’s legitimacy and to civil servants’ sense of self-worth.

For much of the 1980s, the ZANU(PF) government successfully capitalised on its success in the liberation war and its substantial victory in the independence elections. It was thus able to build a network of informal alliances with many of its former supporters and enemies (Dorman Reference Dorman2016). This coalition incorporated disparate elements such as white farmers, former Rhodesian politicians and Western donors. The ‘politics of inclusion’, to use Sara Rich Dorman’s (Reference Dorman2016: 33) phrase, became emblematic of ZANU(PF)’s early approach to nation- and party-building.

The post-independence government was nevertheless confronted with a series of choices and disputes as it attempted to reshape society and make a reality of its vision for the nation. Profound structural concerns such as post-war reconstruction and repurposing the inherited colonial political economy – especially redressing its racialised imbalances – existed alongside political challenges such as democratising the authoritarian colonial state and its institutions (Muzondidya Reference Muzondidya, Raftopoulos and Mlambo2009; Mlambo Reference Mlambo2014; Dorman Reference Dorman2016). Equally difficult was the task of nation-building in a society with deep fissures along the lines of race, ethnicity, class, gender and geography. Such social divisions were compounded by the legacies of the liberation struggle on the country’s political culture.

In this way, an uneven and contradictory picture of Zimbabwe’s ‘development’ emerged in the 1980s. Dorman (Reference Dorman2016: 45) notes that ‘development’ proved a compelling motivating force for government ideology – ‘encapsulating all that had been denied by the Rhodesian regime’. In this the country received fervent support from a range of aid agencies and donors. The government implemented a policy of ‘national development’ that included the expansion and extension of public services to the black majority, especially in health and education, where it made notable achievements (Auret Reference Auret1990; Muzondidya Reference Muzondidya, Raftopoulos and Mlambo2009; Mlambo Reference Mlambo2014). The government expanded access to health facilities throughout most of the country: it restored 161 clinics that had been damaged during the war, built 163 new health centres and legislated free medical care for the poor. Regarding public health and preventative services, the government ran child immunisation schemes, nutrition and hygiene awareness campaigns, and family planning programmes. By 1990, Zimbabwe had the lowest child malnutrition rate in Africa as well as maternal and child mortality rates considerably lower than the continental average. The World Bank (1992: 7) cited Zimbabwe’s achievements in health as ‘truly impressive’ in light of the above and other achievements.

Such accomplishments notwithstanding, James Muzondidya (Reference Muzondidya, Raftopoulos and Mlambo2009: 169) characterises the gains made in the first decade of independence as ‘limited, unsustainable and ephemerally welfarist in nature’. At a macro level, he contends that Zimbabwe continued to experience serious social and economic problems as well as redistributive challenges throughout the decade, especially in the spheres of land and the economy. Moreover, the economic boom of the immediate post-independence period was short-lived. At best, the economy experienced mixed fortunes during that time, as it went through the deleterious effects of droughts, weakening terms of trade, and high interest rates and oil prices. These factors diminished the state’s capacity to finance its redistributive programmes.

Critiques of the Zimbabwean government’s programme of ‘development’ can be taken further still. Gavin Williams (Reference Williams2003) reminds us that ‘development is not a thing, it is an idea’ – one whose polyvalent articulations give rise to overlapping, competing and contradictory politics, policies and programmes. In early post-colonial Zimbabwe, we see at least two radically different conceptions of development at play. On one hand, the new government presented ‘the Zimbabwean people’ as the drivers and beneficiaries of a nationwide and inclusive development project, especially as it sought to create distance between itself and the top–down development projects of the colonial era. As was en vogue in the late 1970s and early 1980s development discourse (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1990), the new ruling party advocated a bottom–up and people-driven version of development (McGregor and Ranger Reference McGregor and Ranger2000; see also Nustad Reference Nustad2001). The words of the newly inaugurated prime minister, Robert Mugabe (cited in Zimbabwe Government 1981), captured this sentiment best: ‘Government is determined to embark on policies and programmes designed to involve fully in the development process the entire people, who are the beginning and end of society, the very asset of the country and the raison d’être of Government.’ On the other hand, the ruling party, or elements within it, was also committed to its own vision of modernising development and orderliness.

Dorman (Reference Dorman2016) sees the logics of coercive unity and top–down development as well as ZANU(PF)’s monolithic interpretations of citizenship – Shona-speaking, bearing totems, disciplined and making productive use of land – in both urban and rural areas. Additionally, a combination of the external threat from apartheid South Africa, persistent Cold War tensions and the strength of the inherited Rhodesian security state allowed for the continuation of a strong militaristic tendency by the ZANU(PF) government (Alexander, McGregor and Ranger Reference Alexander, McGregor and Ranger2000; Dorman Reference Dorman2016). Repressive legislation from the Rhodesian era was retained, along with an extended state of emergency (Mlambo Reference Mlambo2014).

While my focus is on urban history, it is worth briefly mentioning how the ruling party dealt with significant challenges to its authority in rural areas in the 1980s, especially in the Midlands and Matabeleland provinces (largely Ndebele-speaking areas), in the form of ZAPU, its military wing and its civilian supporters.

The ceasefire of 21 December 1979 brought Zimbabwe’s liberation war to an end. As already noted earlier in this chapter, this was a time of optimism but also one of ongoing insecurity and violence. Throughout the country, suspicious guerrillas from erstwhile antagonistic militaries and guerrilla movements had to turn themselves in to Assembly Points (APs), while long-secretive political cadres had to come into the open and order had to be consolidated to pave the way for elections. The loser in Zimbabwe’s first national elections, ZAPU, soon found itself embroiled in political conflict, with devastating repercussions for its armed wing, the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army, known as ZIPRA. Alexander, McGregor and Ranger (Reference Alexander, McGregor and Ranger2000) offer a compelling and granular account of this period in their in-depth monograph, Violence and Memory: One Hundred Years in the ‘Dark Forests’ of Matabeleland. They note that partisan accounts of the post-independence conflict have portrayed it

as the product of an ill-judged bid by ZAPU to claim the victory it had failed to gain through the ballot box, as a cynical attempt by ZANU(PF) to use the incidents of violence in the early 1980s as pretext to crush the only real obstacle to its total supremacy, or as an attempt by South Africa to exploit tensions between ZANU(PF) and ZAPU, whites and blacks, so as to leave its newly independent neighbour in disarray.

As a challenge to such characterisations, these authors argue that post-independence insurgency was largely a result of distrust within, and then repression by, the newly formed Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA). During the liberation struggle, the two guerrilla armies’ regional patterns of recruitment and operation had left ZIPRA forces dominated by Ndebele speakers from Matabeleland while the Zimbabwe National Liberation Army (ZANLA), the military wing of ZANU, was predominantly Shona speaking. Additionally, the guerrilla movement’s operational areas maintained significance in terms of political loyalties: voting largely, though not completely, followed ethnic and regional divisions, creating the possibility for conflict along these lines after independence.

In brief, after the ceasefire, guerrillas were summoned to gather in designated APs from which they would be demobilised or integrated into the nascent ZNA. However, many guerrillas refused to come in to APs and regularly cached arms and ammunition. While their motives were diverse, the most important was a pervasive fear that they would be bombed or attacked while concentrated in the APs, since the Rhodesian Army was, at this time, still very much intact. Internecine conflict soon ensued in the early 1980s within and beyond the ZNA involving newly formed state security forces, ex-combatants from both guerrilla movements, and civilians, who were drawn into the violence in complex ways.

In January 1983, Robert Mugabe’s government launched a massive security clampdown in Matabeleland and parts of Midlands, led by a North Korean–trained division of the ZNA, known as the Fifth Brigade and itself a predominantly Shona-speaking formation (Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace in Zimbabwe 1997). Furthermore, this deployment coincided with the imposition of a strict curfew in the region. It soon became clear that the Fifth Brigade was not interested in seeking out ‘dissident’ soldiers from ZIPRA. Thousands of atrocities such as murders, mass physical torture and the burnings of property occurred in the weeks thereafter. Members of the unit declared to locals that they had been ordered to ‘wipe out the people [Ndeble] in the area’ and to ‘kill anything that was human’ (Alexander et al. Reference Alexander, McGregor and Ranger2000: 222).

The Fifth Brigade’s motto was Gukurahundi (a ChiShona language term which loosely translates as ‘the early rain which washes away the chaff before the spring rains’). Richard Werbner documents that peasants in Matabeleland said that they were the rubbish that the Shona wished to clear away (Werbner Reference Werbner1991). While the Fifth Brigade was active for a year, political and ethnic violence continued for much longer. The Zimbabwean human rights advocate and forensic anthropologist, Shari Eppel, estimates the total number of unarmed civilians who died throughout the entire Gukurahundi period to be ‘no fewer than 10,000 and no more than 20,000’ (cited in Cameron Reference Cameron2017). The precise figure remains uncertain. In addition to the killings, thousands more were arbitrarily arrested, detained without charge, beaten, tortured and raped, resulting in an intense atmosphere of fear and mistrust among the Ndebele.

The 1987 Unity Accord marked the end of the conflict and formally integrated the principal opposition party, ZAPU, into the ruling party under the existing moniker ZANU(PF). Authority was further centralised through the instatement of an Executive Presidency, held by Robert Mugabe. The massacres foreshadowed a number of traits that would mark the authoritarian statism under the ruling party after 2000, namely the ‘excesses of a strong state, itself in many ways a direct Rhodesian inheritance, and a particular interpretation of nationalism’ (Alexander et al. Reference Alexander, McGregor and Ranger2000: 6).

In urban areas, Dorman points out that in the early 1980s, little changed with respect to the nature of the policies that were applied to governing the city, specifically the townships. Colonial era bylaws, plans and statutes largely remained in situ (Dorman Reference Dorman2015). There was an apparent tension between the imperative of overturning the racial and socio-economic segregation of Rhodesian city planning and that of maintaining a modern and orderly sense of urban space. In terms of housing, former ‘white’ suburbs in Harare were renamed ‘low density neighbourhoods’, and middle-class Black, Asian and Coloured families moved into them (Cumming Reference Cumming, Lovemore, Daniel and Sioux1993). Meanwhile urban high-density neighbourhoods expanded but few new suburbs were developed. Despite government plans in the early 1980s to build 115,000 units across the country, by 1985 only 13,500 were complete, and waiting lists grew longer and longer in the cities. With curbs lifted on racial segregation, the shortage of housing compelled impoverished urban arrivals to construct ‘illegal’ shelters in the townships.

In response, the government launched ‘an almost unyielding battle against informal housing’ from the 1980s onwards, and the antipathy of the Harare authorities to informal settlement, derisively called ‘squatting’, has ‘remained a recurrent issue throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and into the twenty-first century’ (Potts Reference Potts, Murray and Myers2006a: 271). As such, the rational and modernising mission that had been espoused by the colonial state was retained, and ‘squatting’ was viewed by the new government as disruptive of this because it indicated improper land use and was seen as an encroachment on urban orderliness (Alexander Reference Alexander2006; Tendi Reference Tendi2010). In 1984, as reported by Potts and Mutambirwa (Reference Potts and Mutambirwa1991), there were eight ‘squatter’ settlements in Harare but forty-two others had been ‘cleared’. Such processes showed little respect for the desperate urban poor who had resorted to ‘squatting’ out of economic necessity (Dorman Reference Dorman2016). Similarly, attempts were made to keep the central business district ‘clean’ and ‘modern’. In striking continuity with colonial discourses, policies and practices, only formal businesses were supposed to operate in the city while informal markets and vendors were banned. In 1983, ‘Operation Clean-up’ was launched, and police arrested over 6,000 women in urban areas ostensibly to rid the streets of prostitution. In actuality, the arrested women included schoolgirls, women with babies and the elderly, many of whom were apprehended while commuting between work and home (Dorman Reference Dorman2016).

By the end of the 1980s, Deborah Potts (Reference Potts, Murray and Myers2006a) writes, it was evident that major contradictions and conflicts were arising between the needs of the urban poor and the desire and commitment of local urban authorities to maintain what they saw as an aesthetically pleasing and ‘modern’ urban environment, which conformed to planned land use schemes. The policing and eradication of illegal, ‘squatter dwellings’ was pursued with great vigour and to tremendous effect for most of the post-independence era. Thus, the government’s efforts to maintain ‘order’ and a modern city image in Zimbabwe meant that the visual difference between Harare and most other major sub-Saharan African, let alone Asian or Latin American, cities in the 1980s and 1990s, and even into the early twenty-first century, was remarkable. While informal sector activities and begging were present on the street in the city centres, these were contained on a minor scale (Potts Reference Potts, Murray and Myers2006a). No other African country, Potts observes, has maintained such continuity of official resistance to informal settlements (Potts Reference Potts, Murray and Myers2006a: 284).

The ‘galloping urbanism’ of Harare at a population growth of over 5 per cent per year throughout the 1980s severely burdened the capacity of both central and local governments to provide accommodation and basic urban amenities for the urban poor (Musemwa Reference Musemwa, Chiumbu and Musemwa2012). From a water perspective, Harare’s provisions had been relatively stable in the early 1980s. This was mainly because of the new Manyame Dam that had been built in 1976 to augment the city’s water supplies (Musemwa Reference Musemwa2006). Over the next ten to fifteen years and following the severe droughts of 1982–88 and much of the early 1990s, Harare, like other parts of the country, began to experience much more serious water shortages resulting from both ecological and political-economic factors.

The ‘statist’ economy of the 1980s may have succeeded in delivering many social welfare benefits to Zimbabweans while enjoying a growth rate of 4 per cent per year from 1986 to 1990 (Carmody and Taylor Reference Carmody and Taylor2003), but it was not without its contradictions. An overvalued currency; arrears to international lenders; shortages of diverse essential goods such as paper, cement and vehicles; and the failure to adequately reduce pressures on land and achieve restitution in communal areas all contributed to the weakening of the national economy, the delivery of public services and ZANU(PF)’s political legitimacy (Muzondidya Reference Muzondidya, Raftopoulos and Mlambo2009; Alexander Reference Alexander, Mustapha and Whitfield2010; Mlambo Reference Mlambo2014; Dorman Reference Dorman2016).

Under domestic and international pressure to address these political-economic conditions, the government implemented reforms in the form of an economic structural adjustment programme (ESAP). The ESAP package contained the standard features of IMF and World Bank economic reform strategies, including, inter alia: a reduction in the budget deficit through a combination of cuts in public enterprise deficits and rationalisation of public sector employment; devaluation of the local currency; trade liberalisation, including price decontrol, and deregulation of foreign trade, investment and production; phased removal of subsidies; and the introduction and enforcement of cost recovery measures in health and education sectors (Bijlmakers, Bassett and Sanders Reference Bijlmakers, Bassett and Sanders1996). The latter sectors were badly affected by structural adjustment as evidenced by steep declines in key health and education indicators. Real per capita expenditure on health through the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare fluctuated dramatically in the 1990s, resulting in widespread difficulties in attracting and retaining qualified healthcare staff, the decreasing availability of drugs and medical equipment, the poor maintenance of buildings and the general decline in the quality of health services (Bijlmakers et al. Reference Bijlmakers, Bassett and Sanders1996). From the patients’ perspective, the introduction of cost recovery measures, specifically user fees, is thought to have profoundly altered health-seeking behaviour and diminished access to clinical care, especially among poor Zimbabweans, according to seminal studies at the time (Gibbon Reference Gibbon and Gibbon1995; Bijlmakers et al. Reference Bijlmakers, Bassett and Sanders1996, Reference Bassett, Bijlmakers and Sanders1997).

The economic reforms of the 1990s led to a deterioration of urban living conditions through the expansion of the informal economy, as a consequence of unemployment and retrenchment, and the persistence of inadequate water and sanitation services. In high-density areas, exasperation with the delayed promise of development was amplified by the changes in living standards throughout the decade. At the end of the 1990s, it was evident that government policies would fail to meet their 1985 target of housing for all by the year 2000. In 1991, it was estimated that there was a deficit of 70,000 dwellings in Harare, based on the housing waiting list, which by 1994 had increased to 92,251 households (Dorman Reference Dorman2015). Homeowners responded to the demand for affordable housing, and their own declining incomes, by renting out rooms and backyard shacks to lodgers. Unable to spill over into vacant land, Harare’s townships accommodated increasing numbers of people within limited space, resulting in more informal trade and worsening public health standards in terms of overcrowded housing and reduced access to clean water and sanitation facilities. Reactions to visible urban poverty were contradictory. Initially, as explained earlier in the chapter, the government had implemented ‘clear-ups’ and the forced removal of ‘squatters’. From the 1980s to the 1990s, street-kids and the destitute were targeted for removal to holding camps, training centres and former refugee camps. However, as the 1990s wore on, tolerance of the informal economy seemed to increase. As Daniel Tevera and Amos Chimhowu’s (Reference Chimhowu and Tevera1998) study of backyard shacks in Harare, concluded in the late 1990s,

[T]he general mood has shifted from intolerance during the ‘socialist era’ of the 1980s to tolerance during the 1990s. The need to maintain a rapidly eroding political power base and to soften the impact of political hardships … has compelled both central government and the Harare city council to grudgingly allow the proliferation of backyard shacks in the low-income residential areas.

The adoption of unpopular economic reform measures undermined the ‘state expansion and social advance of the 1980s and, as a result, the government’s ability to pursue its programme of modernising development’ (Alexander Reference Alexander, Mustapha and Whitfield2010: 188). Additionally, the unbudgeted payouts to ‘war veterans‘ through a pension fund in 1997 – to maintain their loyalty to the ruling party – as well as the tremendously high cost of involvement of the Zimbabwe government in the war in DRC in 1998 added to the failures of the structural adjustment programme by the end of the 1990s (Moore and Raftopoulos Reference Moore, Raftopoulos, Chiumbu and Musemwa2012). Furthermore, damaging allegations of corruption – most infamously the ‘Willowgate’ scandal in which several senior ministers were implicated in the illegal reselling of cars and trucks at much higher prices than they had paid (Dorman Reference Dorman2016) – diminished the popularity of ZANU(PF) in certain constituencies, for example in urban areas and among trade unionists, thereby helping to create space for the emergence of new forms of political opposition through the decade. This culminated in the formation of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) in 1999, a new political party that forged an alliance among a diverse coalition of interests and that presented ZANU(PF) with its first serious electoral challenger since independence in 1980. The ensuing confrontation between the two parties ushered in a period of political disruption and economic upheaval with profound consequence for public service delivery, urban infrastructures and political order.

Disrupting Urban Order: The City and the Crisis

The 2000s witnessed a major urban crisis in Zimbabwe. Manifest as a series of resource-based emergencies, such as fuel, food and electricity shortages, this crisis was rooted in the country’s economic meltdown and political conflicts (Ranger Reference Ranger2007; Raftopoulos Reference Raftopoulos, Raftopoulos and Mlambo2009; J. L. Jones Reference Jones2010b; Chiumbu and Musemwa Reference Chiumbu and Musemwa2012; Dorman Reference Dorman2015). As Raftopoulos (Reference Raftopoulos, Raftopoulos and Mlambo2009: 201–02) explains,

This upheaval consisted of a combination of political and economic decline that, while it had its origins in the long-term structural economic and political legacies of colonial rule as well as the political legacies of African nationalist politics, exploded onto the scene in the face of a major threat to the political future of the ruling party, ZANU(PF). The crisis became manifest in multiple ways: confrontations over the land and property rights; contestations over the history and meanings of nationalism and citizenship; the emergence of critical civil society groupings campaigning around trade union, human rights and constitutional questions; the restructuring of the state in more authoritarian forms; the broader pan-African and anti-imperialist meanings of the struggles in Zimbabwe; the cultural representations of the crisis in Zimbabwean literature; and the central role of Robert Mugabe.

In the years leading up to the cholera outbreak, the ruling party deployed an array of legal, coercive and patronage strategies to transform state bodies from bureaucratic to partisan institutions (Kamete Reference Kamete2006; Ranger Reference Ranger2007; Muchaparara Musemwa Reference Musemwa2008a; Alexander and McGregor Reference Alexander and McGregor2013; McGregor Reference McGregor2013). Terence Ranger (Reference Ranger2007) describes how the ZANU(PF) government, especially since 2000, dismissed elected executive mayors; sacked whole municipal councils; and appointed partisan commissions to run the cities. The Combined Harare Residents’ Association (CHRA) – an umbrella community-based organisation that aims to represent and support all residents of Harare by advocating for effective, transparent and affordable municipal and other services – identified the Urban Councils Act as integral to ZANU(PF)’s strategies for seizing greater control of local government:

On the one hand it bestows a degree of local autonomy to residents through local council elections, yet on the other it confers almost dictatorial power upon the Minister of Local Government … This legislative confusion has given rise to the serious conflict that has undermined the good governance of the capital city.

ZANU(PF)’s actions were triggered by its defeat at the polls in urban areas from 2000 onwards. In February 2000, the ruling party supported a new constitution, which was decided upon in a national referendum. The proposal was unexpectedly defeated and was taken as both a personal rebuff for President Robert Mugabe and a political triumph for the newly formed opposition. In June, Harare’s electorate, like their urban counterparts across the country, rejected ZANU(PF)’s bid to represent them in parliament (Kamete Reference Kamete2006). All nineteen constituencies elected opposition MDC Members of Parliament. Subsequently, in the council and mayoral polls of March 2002, the electorate again voted against ZANU(PF) candidates thereby stripping the ruling party of all vestiges of democratic representation in the capital. And in the simultaneous presidential polls, Harare voted overwhelmingly in favour of Morgan Tsvangirai. To all intents and purposes, ZANU(PF) had become ‘a rural party’. The defeats of 2000 spurred ZANU(PF) into action, and the party sought to reassert its dominance in urban politics – to re-urbanise, as it were. In the process of trying to regain urban control, ZANU(PF) turned urban governance into the object of intense political struggle, and drastically undermined the capacity of councils to deliver services. The ruling party’s strategy hinged on recentralising powers over local authorities, developing a system of patronage through and beyond local state institutions, creating ‘parallel’ party hierarchies and using party-aligned militia to control key urban spaces and access to resources (McGregor Reference McGregor2013).

An integral element of the ruling party’s strategy was the ‘reassertion’ of formal planning, which resonated with people’s memories of past (both colonial and post-colonial) enforcement of urban regulations, limitations on informal markets, and sometimes evictions and clearances (Fontein Reference Fontein2009). Potts (Reference Potts2006b: 291) explains the overarching motivations of the ‘slum clearances’ and demolition exercises that followed as threefold:

a desire to punish the urban areas for their almost universal tendency since 2000 to vote for the opposition MDC; an ideological adherence to modernist planning and the associated image of a ‘modern’ city; and a desire to decrease the presence of the poorest urban people, by driving them out of the towns, because of an incapacity to provide sufficient and affordable food and fuel for them.

The most notorious ‘clearance’ was launched on 19 May 2005, when Sekesai Makwavarara, chair of the government-appointed and unelected Harare Commission that was running the city, announced that the City of Harare intended to embark on Operation Murambatsvina (meaning ‘Restore Order’ or ‘Drive Out the Rubbish’), a programme to

enforce by-laws to stop all forms of illegal activities. These violations of the by-laws in areas of vending, traffic control, illegal structures, touting/abuse by rank marshals, street life/prostitution, vandalism of property infrastructure, stock theft, illegal cultivation among others have led to the deterioration of standards thus negatively affecting the image of the City. The attitude of the members of the public as well as some City officials has led to a point whereby Harare has lost its glow. We are determined to bring it back … It is not a once-off exercise but a sustained one that will see to the clean-up of Harare … Operation Murambatsvina is going to be a massive exercise in the CBD [Central Business District] and the suburbs which will see to the demolition of all illegal structures and removal of all activities at undesignated areas.

What followed, dubbed by many as ‘Zimbabwe’s tsunami’, was a massive campaign – unprecedented in scale and duration throughout the history of urban Africa, including in apartheid South Africa – of forced evictions from ‘illegally squatted’ areas as well as bulldozers flattening informal markets and homes, offering owners and inhabitants only minutes to remove property (Potts Reference Potts2006b; Fontein Reference Fontein2009). This was especially so in high-density areas across Harare and other cities. The most authoritative report, written by Anna Tibaijuka (Reference Tibaijuka2005), the UN Special Envoy on Human Settlement Issues in Zimbabwe, conservatively estimated that around 650,000–700,000 people had lost either their homes or the basis of their livelihoods, or often both, during the operation. These findings were derived from the government’s own estimates and average household size, and information gathered from a range of different organisations and individuals within the country.

Despite official pronouncements about the need to ‘restore order’ – to reassert formal planning procedures, bylaws and local state institutions – Operation Murambatsvina was experienced as the arbitrary, extreme and often violent execution of state power by council officials, police and the military, which for many seemed to operate outside the bounds of a legitimate and bureaucratic authority (Fontein Reference Fontein2009). Enforcing the sense of sinister intent behind the demolition and clearances exercises, Police Commissioner Augustine Chihuri reportedly said that the purpose of the operation was ‘to clean the country of the crawling mass of maggots bent on destroying the economy’ (cited in Tibaijuka Reference Tibaijuka2005). In my own interviews with township residents, the operation still evokes painful memories of being assaulted by the state and plunged into homelessness, destitution and ‘suffering.’ Even just mentioning it stirred difficult emotions for Paida, resident in Norton, ‘Murambatsvina. You’re making me think. Sometimes, you mustn’t think about that because you will hate life.’Footnote 2 Moreover, if the aim was to restore Harare’s ‘sunshine’ status, Murambatsvina often created more squalor than it removed (Fontein Reference Fontein2009). In many cases, good-quality housing was destroyed, only to be replaced by ramshackle, temporary structures – previously a rare sight in Zimbabwe even if characteristic of so many informal urban settlements across the continent. And, notably, many township residents blamed Operation Murambatsvina for creating the conditions that allowed cholera to spread in urban areas: ‘[T]hey are partially to blame for that cholera. That outbreak occurred soon after Murambatsvina, so there was dilapidation of infrastructure. Even here there was a toilet outside and it was destroyed. It worsened the outbreak.’Footnote 3

Conclusion

In this chapter, I have provided a focussed history of Harare’s urban environment and the fraught politics of orderliness, social control, development and disruption that have shaped it. Through my discussion of how national and local governments have, at different points in history, intruded into the economic and social life of township residents, two salient themes for the study of the politics of cholera are apparent. First, the problems of urban overcrowding and the difficulties of delivering public services, including water and sanitation, to high-density areas are enduring, and they predisposed Harare’s townships to diarrhoeal disease outbreaks. These patterns were neither arbitrary nor accidental, but were the outcomes of strategies of social control, political repression, myopic urban planning and racist ideas of African impermanence in the city. Second, in the post-colonial period, the formal extension of civil and political rights to township residents was not sufficiently accompanied by improvements in social and economic conditions. The townships have remained an ambiguous space of inclusion and exclusion. Urban residents have enjoyed greater freedoms in the city through the lifting of pass laws and segregation, but they have also been subjected to projects of formal ‘planning’ and the ‘reassertion’ of order, such as demolition exercises, which have resulted in dispossession and displacement. As will become even clearer in the next chapter, it was the urban poor who were most affected by Zimbabwe’s rapidly declining basic public services as well as by the urban planning and ‘order’ to which official justifications of Operation Murambatsvina appealed (Fontein Reference Fontein2009).

This chapter has also discussed ZANU(PF)’s angry reaction to what it saw as illegitimate challenges to its authority. The ruling party fought back on multiple fronts, using legal, militaristic and patronage strategies to take over state institutions, manipulate elections, discredit and undermine the opposition, and reassert its presence in urban areas. These changes had profound ramifications for state institutions and social services. The next chapter examines these changes more forensically through a two-stage analysis: a dissection of how the post-2000 crisis precipitated the cholera outbreak; and an examination of how the outbreak unfolded and which factors perpetuated its spread.