Introduction

Mental health is critical to public health and contributes substantially to the global burden of disease (Whiteford et al., Reference Whiteford, Ferrari, Degenhardt, Feigin and Vos2015). In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), there are few resources to address this burden, resulting in large numbers of people with mental health concerns not receiving treatment (Demyttenaere et al., Reference Demyttenaere, Bruffaerts, Posada-Villa, Gasquet, Kovess, Lepine, Angermeter, Bernert, De Girolamo, Morosini, Polidori, Kikkawa, Kawakami, Ono, Takeshima, Uda, Karam, Fayyad, Karam, Mneimneh, Medina-Mora, Borges, Lara, De Graaf, Ormel, Gureje, Shen, Huang, Zhang, Alonso, Haro, Vilagut, Bromet, Gluzman, Webb, Kessler, Merikangas, Anthony, Von Korff, Wang, Brugha, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Lee, Heeringa, Pennell, Zaslavsky, Ustun and Chatterji2004). Calls have been made to make evidence-based treatments for mental disorders more accessible by integrating them into non-specialised health settings, such as primary, maternal and child care systems (Lancet Global Mental Health Group et al., Reference Chisholm, Flisher, Lund, Patel, Saxena, Thornicroft and Tomlinson2007).

There are a number of compelling reasons to integrate mental health services into routine maternal and child health care in LMICs. First, mental disorders in the perinatal period are common and disabling (Baron et al., Reference Baron, Hanlon, Mall, Honikman, Breuer, Kathree, Luitel, Nakku, Lund, Medhin, Patel, Petersen, Shrivastava and Tomlinson2016). Second, maternal mental disorders are associated with poor child development and health (Surkan et al., Reference Surkan, Kennedy, Hurley and Black2011). Third, maternal and child health care settings provide good entry points for identification and treatment of maternal mental disorders because of the relatively good uptake of antenatal care in LMICs. Fourth, treatments for maternal mental disorders have been evaluated as effective in multiple LMICs and existing treatment guidelines for non-specialised providers include specific recommendations for pregnant women (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Fisher, Bower, Luchters, Train, Yasamy, Saxena and Waheed2013).

Despite demonstrated links in the epidemiological literature, few systematic investigations have been conducted to examine whether maternal mental health (MMH) interventions can reduce potential negative impacts on children's outcomes. The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic. Specifically, our research question was: do interventions with a dedicated psychiatric or psychosocial component delivered to pregnant women and mothers during the perinatal period improve children's health and development in LMICs relative to standard antenatal care or interventions lacking a dedicated psychiatric or psychosocial component?

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, PsycInfo, Cochrane CENTRAL, Embase, Web of Science, CINAHL, Popline, several grey literature sources (Global Health Library, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, Emergency Nutrition Network, ALNAP and Eldis) and trial registration websites (clinicaltrials.gov). The searches were conducted through May 2020 without date, publication or language restrictions. Search strategies contained terms describing the perinatal period (e.g. ‘prenatal’, ‘postpartum’), mental and psychosocial health (e.g. ‘psychosocial’, ‘anxiety’, ‘depression’), LMICs (e.g. ‘low-income’, ‘developing country’, list of LMICs), randomised trial (e.g. ‘randomized’) and child development (e.g. ‘child growth’, ‘child development’, ‘nutrition’; online Supplementary material).

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for our systematic review if the study: (1) described interventions delivered during the perinatal period, defined as pregnancy through 1-year post-partum; (2) incorporated an MMH intervention component; (3) included a MMH outcome; (4) was conducted in an LMIC (http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups) and (5) included a child health, nutrition or development outcome. We retained the child outcomes for inclusion broad since this is (to our knowledge) the first systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic. All non-randomised, non-controlled studies were excluded. We did not limit our results to studies that restricted their samples to women with mental health problems.

Two independent reviewers assessed titles and abstracts from all searches. English and Spanish full texts were retrieved for potentially relevant articles and assessed by two reviewers independently to evaluate eligibility. Inter-rater reliability in the full text review was 74.4%. Articles and abstracts in other languages (two in Farsi) were assessed by a single reviewer that was fluent in the language. This reviewer worked with another member of the research team to review eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

Data collection, risk of bias assessment and GRADE certainty of evidence

Two reviewers independently extracted data on study design, sample, study conditions, child-related outcomes, results and risk of bias for each included trial (MCG, MEL, see ‘Acknowledgements’). Quantitative results were extracted using the unadjusted means and standard deviations for continuous outcomes and the number of events and denominator for dichotomous outcomes. The risk of bias assessment followed the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool where reviewers rated several potential sources of bias as ‘high’, ‘low’ or ‘unclear’ risk in relation to random sequence generation, allocation concealment, masking of participants/personnel, masking of outcome assessors, attrition, reporting and any other sources of bias of each trial (Higgins and Greene, Reference Higgins and Greene2011). We considered overall risk of bias to be high if trials displayed high risk of bias in two or more of these seven domains. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

We employed the GRADE approach to assess the overall certainty of evidence and to interpret findings (Barbui et al., Reference Barbui, Dua, Van Ommeren, Yasamy, Fleischmann, Clark, Thornicroft, Hill and Saxena2010). We adhered to the standard methods for the preparation and presentation of results outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and PRISMA guidelines (Higgins and Greene, Reference Higgins and Greene2011). We included the following outcomes in the GRADE evidence profiles: exclusive breastfeeding, cognitive development, psychomotor development, low birth weight, weight (continuous), height (continuous), underweight (i.e. weight-for-age z-score <−2), stunting (i.e. height-for-age z-score <−2) and weight-for-height.

Data analysis

Narrative synthesis: included trials were compared with respect to population, intervention, measurement and methodological features that may contribute to clinically relevant heterogeneity in the synthesis of the results. Reporting of these results followed PRISMA recommendations.

Quantitative synthesis: data from included trials were pooled using a random effects model for outcomes reported in at least two trials and expressed as relative risk (RR) for categorical data, and standardised mean difference (SMD) for continuous data. For categorical outcomes with evidence supporting an intervention effect across more than one study, we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) to provide benefit (Furukawa et al., Reference Furukawa, Guyatt and Griffith2002). Review Manager was used for all analyses (The Nordic Cochrane Center, Reference Collaboration2014). Data from cluster RCTs were adjusted with an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC). If the ICC was not available, we assumed it to be 0.05 (Higgins and Greene, Reference Higgins and Greene2011). Below, we report intention-to-treat analyses including all randomised patients.

We conducted a sub-group analysis by intervention type: (1) focused MMH interventions (i.e. interventions mainly aimed at improving MMH) and (2) integrated interventions (i.e. interventions that included a mental health focused component, but also focused on other outcomes). We evaluated publication bias for outcomes that included more than ten studies.

Results

Searches yielded 13 918 results, with an additional 48 records identified through cross-referencing and expert recommendation (Fig. 1). After removal of duplicates (n = 1921), 12 045 articles were screened. Reviewers identified 273 articles that were potentially relevant and thus included in full text screening. Thirty-six articles representing 21 randomised trials met criteria for inclusion in this systematic review and seven articles were classified as awaiting assessment because eligibility could not be adequately evaluated given available information (Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Leiva, Undurraga, Krause, Perez, Cuadra, Campos and Bedregal2011; Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Undurraga, Gomez, Leiva, Simonsohn, Navarro and Olisah2012; Akbarzadeh et al., Reference Akbarzadeh, Dokuhaki, Joker, Pshva and Zare2016; Shirazi et al., Reference Shirazi, Azadi, Shariat and Niromanesh2016; Frith et al., Reference Frith, Ziaei, Frongillo, Khan, Ekstrom and Naved2017; Kahalili et al., Reference Kahalili, Navai, Shakiba and Navidian2019; Tran et al., Reference Tran, Fisher, Tuan, Tran, Nguyen, Biggs, Hanieh and Le2019). The most common reasons for exclusion were studies that described an intervention that did not aim to improve MMH and studies that did not include a child outcome (Fig. 1). The 36 included articles represent data from 21 RCTs and 28 284 mother–child dyads.

Fig. 1 . PRISMA flow chart summarising selection of included studies.

Overview of study characteristics and quality

Population: most trials were conducted in upper-middle-income countries (Brazil, Chile, China, Iran, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico and South Africa) (Langer et al., Reference Langer, Campero, Garcia and Reynoso1998; Bastani et al., Reference Bastani, Hidarnia, Montgomery, Aguilar-Vafaei and Kazemnejad2006; Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Linhares, Padovani and Martinez2009; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Tomlinson, Swartz, Landman, Molteno, Stein, McPherson and Murray2009; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Rotheram-Borus, Stein and Tomlinson2014; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b; Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2014; Karamoozian and Askarizadeh, Reference Karamoozian and Askarizadeh2015; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Arteche, Stein and Tomlinson2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Le Roux, Youssef, Nelson, Scheffler, Weiss, O'Connor and Worthman2016b; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Hartley, Le Roux and Rotheram-Borus2016a; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Munro-Kramer, Shi, Wang and Luo2017, Rotheram-Fuller et al., Reference Rotheram-Fuller, Tomlinson, Scheffler, Weichle, Hayati Rezvan, Comulada and Rotheram-Borus2018, Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Scheffler and Le Roux2018; Mohd Shukri et al., Reference Mohd Shukri, Wells, Eaton, Mukhtar, Petelin, Jenko-Praznikar and Fewtrell2019; Nabulsi et al., Reference Nabulsi, Tamim, Shamsedine, Charaffeddine, Yehya, Kabakian-Khasholian, Masri, Nasser, Ayash and Ghanem2019; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Arfer, Chrostodoulou, Comulada, Stewart, Tubert and Tomlinson2019; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Zhang, Mu and Ye2020; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lin, Wang and Bao2020) followed by lower-middle-income (India, Nigeria and Pakistan) (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Tripathy et al., Reference Tripathy, Nair, Barnett, Mahapatra, Borghi, Rath, Rath, Gope, Mahto, Sinha, Lakshminarayana, Patel, Pagel, Prost and Costello2010; Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015; Dabas et al., Reference Dabas, Poonam, Agarwal, Yadav and Kachhawa2019; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla, Tabana, Afonso, De Sa, D'Souza, Joshi, Korgaonkar, Krishna, Price, Rahman and Patel2019; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montogomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Nisar, Tabana, Ain, Bibi, Bilal, Bibi, Liaqat, Sharif, Zulfiqar, Fuhr, Price, Patel and Rahman2019; Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020), low-income (Pakistan) (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015) and a multi-site trial of lower-middle (Cuba) and upper-middle-income countries (Argentina, Brazil and Mexico) (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Farnot, Barros, Victora, Langer and Belizan1992) (Table 1). Most trials enrolled pregnant women in their second and/or third trimester (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Farnot, Barros, Victora, Langer and Belizan1992; Langer et al., Reference Langer, Campero, Garcia and Reynoso1998; Bastani et al., Reference Bastani, Hidarnia, Montgomery, Aguilar-Vafaei and Kazemnejad2006; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Tomlinson, Swartz, Landman, Molteno, Stein, McPherson and Murray2009; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Rotheram-Borus, Stein and Tomlinson2014; Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2014; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b; Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Arteche, Stein and Tomlinson2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Hartley, Le Roux and Rotheram-Borus2016a; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Le Roux, Youssef, Nelson, Scheffler, Weiss, O'Connor and Worthman2016b; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla, Tabana, Afonso, De Sa, D'Souza, Joshi, Korgaonkar, Krishna, Price, Rahman and Patel2019; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montogomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019; Kola et al., Reference Kola, Oladeji, Bello and Gureje2019; Mohd Shukri et al., Reference Mohd Shukri, Wells, Eaton, Mukhtar, Petelin, Jenko-Praznikar and Fewtrell2019; Oladeji et al., Reference Oladeji, Bello, Kola, Araya, Zelkowitz and Gureje2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Nisar, Tabana, Ain, Bibi, Bilal, Bibi, Liaqat, Sharif, Zulfiqar, Fuhr, Price, Patel and Rahman2019; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Zhang, Mu and Ye2020; Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lin, Wang and Bao2020). Four trials enrolled women that had recently given birth (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Linhares, Padovani and Martinez2009; Tripathy et al., Reference Tripathy, Nair, Barnett, Mahapatra, Borghi, Rath, Rath, Gope, Mahto, Sinha, Lakshminarayana, Patel, Pagel, Prost and Costello2010; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Rotheram-Borus, Stein and Tomlinson2014; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b; Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2014; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Hartley, Le Roux and Rotheram-Borus2016a; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Le Roux, Youssef, Nelson, Scheffler, Weiss, O'Connor and Worthman2016b, Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2018, Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Scheffler and Le Roux2018; Dabas et al., Reference Dabas, Poonam, Agarwal, Yadav and Kachhawa2019; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Arfer, Chrostodoulou, Comulada, Stewart, Tubert and Tomlinson2019). Some trials enrolled specific subgroups of pregnant women including adolescents or young adults (Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009), low-income (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Tomlinson, Swartz, Landman, Molteno, Stein, McPherson and Murray2009; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Rotheram-Borus, Stein and Tomlinson2014; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b; Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2014; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Arteche, Stein and Tomlinson2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Hartley, Le Roux and Rotheram-Borus2016a; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Le Roux, Youssef, Nelson, Scheffler, Weiss, O'Connor and Worthman2016b, Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2018, Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Scheffler and Le Roux2018; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Arfer, Chrostodoulou, Comulada, Stewart, Tubert and Tomlinson2019), pregnant with a single foetus, no previous vaginal delivery and no evidence of severe obstetric disease (Langer et al., Reference Langer, Campero, Garcia and Reynoso1998; Mohd Shukri et al., Reference Mohd Shukri, Wells, Eaton, Mukhtar, Petelin, Jenko-Praznikar and Fewtrell2019), high-risk pregnancies (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Munro-Kramer, Shi, Wang and Luo2017) or HIV-positive (Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a). Several trials enrolled subgroups of pregnant women meeting specific mental health criterion including having mild to moderate stress (Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020), elevated anxiety or depressive symptoms (Bastani et al., Reference Bastani, Hidarnia, Montgomery, Aguilar-Vafaei and Kazemnejad2006; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Tomlinson, Swartz, Landman, Molteno, Stein, McPherson and Murray2009; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Arteche, Stein and Tomlinson2015; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Zhang, Mu and Ye2020) screening positive for depression based on PHQ9 ≥ 10 (Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla, Tabana, Afonso, De Sa, D'Souza, Joshi, Korgaonkar, Krishna, Price, Rahman and Patel2019), EPDS ≥ 9 (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Munro-Kramer, Shi, Wang and Luo2017; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lin, Wang and Bao2020), EPDS = 12 (Karamoozian and Askarizadeh, Reference Karamoozian and Askarizadeh2015), anxiety based on the Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Questionnaire (PRAQ) (Karamoozian and Askarizadeh, Reference Karamoozian and Askarizadeh2015) or DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depressive episode (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015).

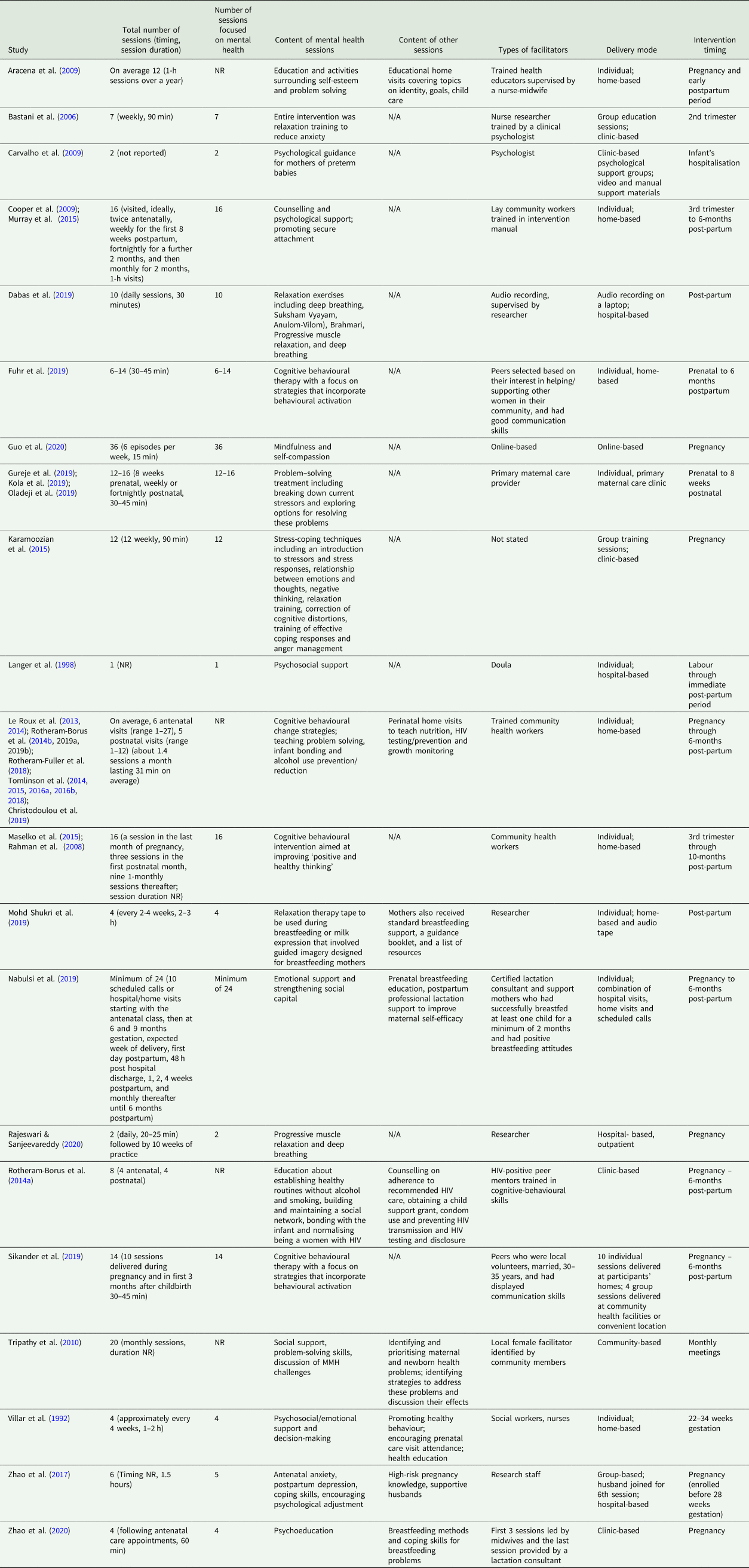

Table 1. Summary of included studies

Exp, experimental group; Con, control group.

Interventions (Table 2): nine trials delivered the intervention through home visits provided by health educators (Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009), peers (Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla, Tabana, Afonso, De Sa, D'Souza, Joshi, Korgaonkar, Krishna, Price, Rahman and Patel2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Nisar, Tabana, Ain, Bibi, Bilal, Bibi, Liaqat, Sharif, Zulfiqar, Fuhr, Price, Patel and Rahman2019), nurses (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Farnot, Barros, Victora, Langer and Belizan1992), certified lactation consultants (Nabulsi et al., Reference Nabulsi, Tamim, Shamsedine, Charaffeddine, Yehya, Kabakian-Khasholian, Masri, Nasser, Ayash and Ghanem2019), community health workers (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Tomlinson, Swartz, Landman, Molteno, Stein, McPherson and Murray2009; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b; Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2014; Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Arteche, Stein and Tomlinson2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Rotheram-Borus, Stein and Tomlinson2014; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Hartley, Le Roux and Rotheram-Borus2016a; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Le Roux, Youssef, Nelson, Scheffler, Weiss, O'Connor and Worthman2016b; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Arfer, Chrostodoulou, Comulada, Stewart, Tubert and Tomlinson2019, Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2018, Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Scheffler and Le Roux2018), social workers (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Farnot, Barros, Victora, Langer and Belizan1992) or a researcher (Mohd Shukri et al., Reference Mohd Shukri, Wells, Eaton, Mukhtar, Petelin, Jenko-Praznikar and Fewtrell2019). Twelve trials delivered the intervention in hospital- or clinic-based settings by nurse researchers (Bastani et al., Reference Bastani, Hidarnia, Montgomery, Aguilar-Vafaei and Kazemnejad2006), primary maternal care providers (Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montogomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019), psychologists (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Linhares, Padovani and Martinez2009), doulas/midwives/lactation consultants (Langer et al., Reference Langer, Campero, Garcia and Reynoso1998; Nabulsi et al., Reference Nabulsi, Tamim, Shamsedine, Charaffeddine, Yehya, Kabakian-Khasholian, Masri, Nasser, Ayash and Ghanem2019; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lin, Wang and Bao2020), peers (Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla, Tabana, Afonso, De Sa, D'Souza, Joshi, Korgaonkar, Krishna, Price, Rahman and Patel2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Nisar, Tabana, Ain, Bibi, Bilal, Bibi, Liaqat, Sharif, Zulfiqar, Fuhr, Price, Patel and Rahman2019) or research staff (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Munro-Kramer, Shi, Wang and Luo2017; Dabas et al., Reference Dabas, Poonam, Agarwal, Yadav and Kachhawa2019; Mohd Shukri et al., Reference Mohd Shukri, Wells, Eaton, Mukhtar, Petelin, Jenko-Praznikar and Fewtrell2019; Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020). One of these interventions was delivered online (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Zhang, Mu and Ye2020), and several supplemented in-person activities with audio/video materials (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Linhares, Padovani and Martinez2009; Dabas et al., Reference Dabas, Poonam, Agarwal, Yadav and Kachhawa2019; Mohd Shukri et al., Reference Mohd Shukri, Wells, Eaton, Mukhtar, Petelin, Jenko-Praznikar and Fewtrell2019). One of these clinic-based trials did not specify the provider (Karamoozian and Askarizadeh, Reference Karamoozian and Askarizadeh2015). The final trial delivered the intervention in community-based settings via a local female facilitator (Tripathy et al., Reference Tripathy, Nair, Barnett, Mahapatra, Borghi, Rath, Rath, Gope, Mahto, Sinha, Lakshminarayana, Patel, Pagel, Prost and Costello2010). The majority of interventions were child-focused, but all contained an MMH component.

Table 2. Intervention details

MMH components included education surrounding self-esteem and/or problem-solving (Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Tripathy et al., Reference Tripathy, Nair, Barnett, Mahapatra, Borghi, Rath, Rath, Gope, Mahto, Sinha, Lakshminarayana, Patel, Pagel, Prost and Costello2010; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Rotheram-Borus, Stein and Tomlinson2014; Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2014; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Hartley, Le Roux and Rotheram-Borus2016a; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Le Roux, Youssef, Nelson, Scheffler, Weiss, O'Connor and Worthman2016b; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montogomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019; Oladeji et al., Reference Oladeji, Bello, Kola, Araya, Zelkowitz and Gureje2019), strengthening social networks (Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a, Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2018, Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Scheffler and Le Roux2018; Nabulsi et al., Reference Nabulsi, Tamim, Shamsedine, Charaffeddine, Yehya, Kabakian-Khasholian, Masri, Nasser, Ayash and Ghanem2019; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Arfer, Chrostodoulou, Comulada, Stewart, Tubert and Tomlinson2019), provision of social, psychological and emotional support (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Farnot, Barros, Victora, Langer and Belizan1992; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Tomlinson, Swartz, Landman, Molteno, Stein, McPherson and Murray2009; Tripathy et al., Reference Tripathy, Nair, Barnett, Mahapatra, Borghi, Rath, Rath, Gope, Mahto, Sinha, Lakshminarayana, Patel, Pagel, Prost and Costello2010; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Arteche, Stein and Tomlinson2015; Nabulsi et al., Reference Nabulsi, Tamim, Shamsedine, Charaffeddine, Yehya, Kabakian-Khasholian, Masri, Nasser, Ayash and Ghanem2019), cognitive-behavioural strategies (Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Rotheram-Borus, Stein and Tomlinson2014; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b; Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2014; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015; Karamoozian and Askarizadeh, Reference Karamoozian and Askarizadeh2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Hartley, Le Roux and Rotheram-Borus2016a; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Le Roux, Youssef, Nelson, Scheffler, Weiss, O'Connor and Worthman2016b, Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2018, Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Scheffler and Le Roux2018; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla, Tabana, Afonso, De Sa, D'Souza, Joshi, Korgaonkar, Krishna, Price, Rahman and Patel2019; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Arfer, Chrostodoulou, Comulada, Stewart, Tubert and Tomlinson2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Nisar, Tabana, Ain, Bibi, Bilal, Bibi, Liaqat, Sharif, Zulfiqar, Fuhr, Price, Patel and Rahman2019), alcohol use prevention (Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b; Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2014; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015, Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2018, Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Scheffler and Le Roux2018; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Arfer, Chrostodoulou, Comulada, Stewart, Tubert and Tomlinson2019), relaxation techniques (Karamoozian and Askarizadeh, Reference Karamoozian and Askarizadeh2015; Dabas et al., Reference Dabas, Poonam, Agarwal, Yadav and Kachhawa2019; Mohd Shukri et al., Reference Mohd Shukri, Wells, Eaton, Mukhtar, Petelin, Jenko-Praznikar and Fewtrell2019; Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020), mindfulness (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Zhang, Mu and Ye2020) and psychoeducation (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Munro-Kramer, Shi, Wang and Luo2017; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lin, Wang and Bao2020). The primary aim of 11 trials was focused specifically on improving MMH via interventions that included relaxation and mindfulness training to reduce anxiety/stress (Bastani et al., Reference Bastani, Hidarnia, Montgomery, Aguilar-Vafaei and Kazemnejad2006; Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020) or depression (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Zhang, Mu and Ye2020), cognitive-behavioural or problem solving therapy to reduce depressive symptoms (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla, Tabana, Afonso, De Sa, D'Souza, Joshi, Korgaonkar, Krishna, Price, Rahman and Patel2019; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montogomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Nisar, Tabana, Ain, Bibi, Bilal, Bibi, Liaqat, Sharif, Zulfiqar, Fuhr, Price, Patel and Rahman2019), psychoeducation to reduce depression and anxiety (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Munro-Kramer, Shi, Wang and Luo2017) and provision of psychological or social support to reduce depression, anxiety or stress (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Farnot, Barros, Victora, Langer and Belizan1992; Langer et al., Reference Langer, Campero, Garcia and Reynoso1998; Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Linhares, Padovani and Martinez2009).

Child outcomes: nutrition and growth outcomes included exclusive breastfeeding (Langer et al., Reference Langer, Campero, Garcia and Reynoso1998; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Rotheram-Borus, Stein and Tomlinson2014; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b; Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Hartley, Le Roux and Rotheram-Borus2016a; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Le Roux, Youssef, Nelson, Scheffler, Weiss, O'Connor and Worthman2016b; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Munro-Kramer, Shi, Wang and Luo2017; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla, Tabana, Afonso, De Sa, D'Souza, Joshi, Korgaonkar, Krishna, Price, Rahman and Patel2019; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montogomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019; Nabulsi et al., Reference Nabulsi, Tamim, Shamsedine, Charaffeddine, Yehya, Kabakian-Khasholian, Masri, Nasser, Ayash and Ghanem2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Nisar, Tabana, Ain, Bibi, Bilal, Bibi, Liaqat, Sharif, Zulfiqar, Fuhr, Price, Patel and Rahman2019; Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lin, Wang and Bao2020), low birth weight (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Farnot, Barros, Victora, Langer and Belizan1992; Bastani et al., Reference Bastani, Hidarnia, Montgomery, Aguilar-Vafaei and Kazemnejad2006; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020) and nutritional status and child growth (e.g. weight-for-age, height-for-age and weight-for-height) (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Rotheram-Borus, Stein and Tomlinson2014; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b; Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Hartley, Le Roux and Rotheram-Borus2016a; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Le Roux, Youssef, Nelson, Scheffler, Weiss, O'Connor and Worthman2016b; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Scheffler and Le Roux2018; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla, Tabana, Afonso, De Sa, D'Souza, Joshi, Korgaonkar, Krishna, Price, Rahman and Patel2019; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montogomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019; Mohd Shukri et al., Reference Mohd Shukri, Wells, Eaton, Mukhtar, Petelin, Jenko-Praznikar and Fewtrell2019; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Arfer, Chrostodoulou, Comulada, Stewart, Tubert and Tomlinson2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Nisar, Tabana, Ain, Bibi, Bilal, Bibi, Liaqat, Sharif, Zulfiqar, Fuhr, Price, Patel and Rahman2019). Child development outcomes were assessed between birth and 84-months post-partum. Psychomotor or cognitive development (Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a; Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Arteche, Stein and Tomlinson2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Scheffler and Le Roux2018; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Arfer, Chrostodoulou, Comulada, Stewart, Tubert and Tomlinson2019) were measured using the Psychomotor Development Scale (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Arancibia and Unurraga1974), the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI-IV) (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1989), the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Syed et al., Reference Syed, Hussein and Mahmud2007), the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS) (Spence, Reference Spence1998), the Bayley Scales (version II) (Bayley, Reference Bayley1993) and the World Health Organization (WHO) gross motor milestones (Wijnhoven et al., Reference Wijnhoven, De Onis, Onyango, Wang, Bjoerneboe, Bhandari, Lartey and Al Rashidi2004). Two trials focused on the mother–child relationship: one trial assessed attachment style (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Tomlinson, Swartz, Landman, Molteno, Stein, McPherson and Murray2009) and one trial measured postpartum bonding (Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a). Several trials also assessed the incidence of infant morbidities and mortality (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Farnot, Barros, Victora, Langer and Belizan1992; Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Tripathy et al., Reference Tripathy, Nair, Barnett, Mahapatra, Borghi, Rath, Rath, Gope, Mahto, Sinha, Lakshminarayana, Patel, Pagel, Prost and Costello2010; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montogomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019; Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020); however, outcome definitions varied substantially between trials. Other outcomes, which were measured in a single trial, include head circumference-for-age (Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013) and number of days in the neonatal intensive care unit (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Linhares, Padovani and Martinez2009).

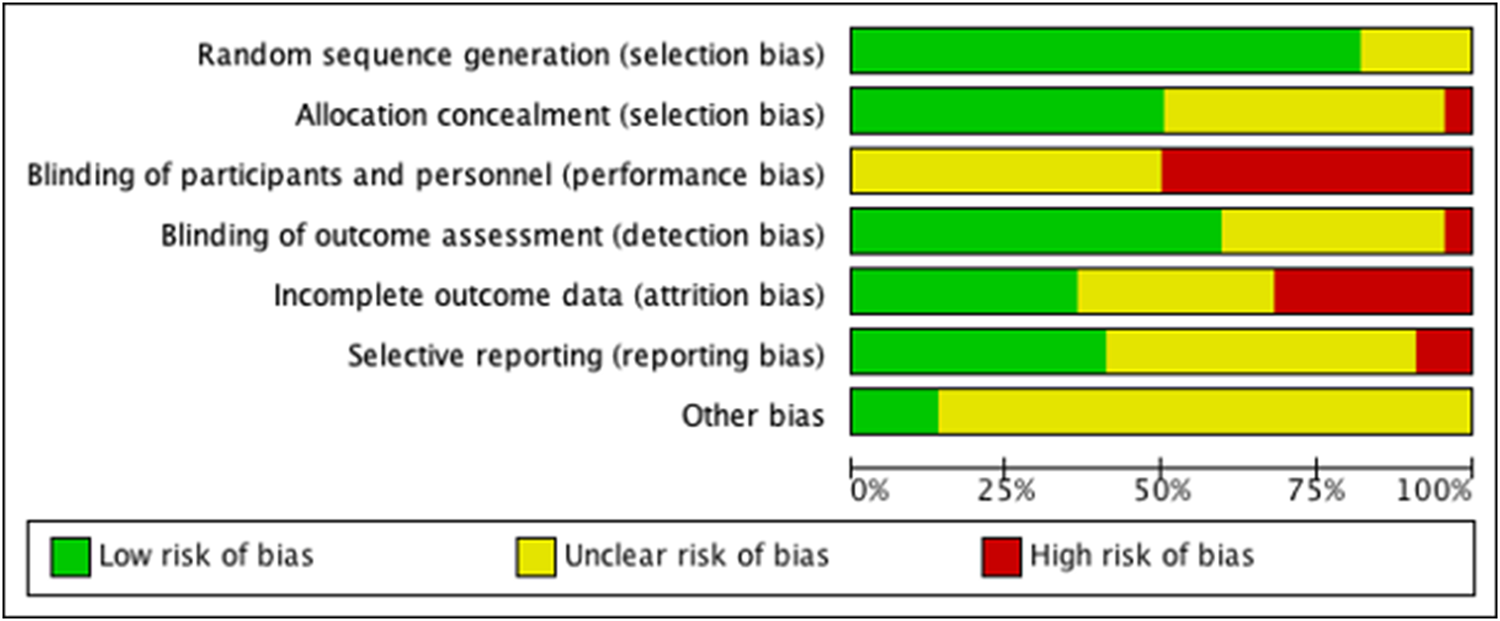

Risk of bias and GRADE certainty of evidence

Few studies showed high risk of bias on two or more of the seven domains assessed in this review. While all included trials were RCTs, three trials did not describe how the randomisation sequence was generated leading to unclear risk of bias. Similarly, the method of allocation concealment was not well described in eight trials. Only ten trials described acceptable methods for blinding outcome assessors. Attrition and selective outcome reporting were common sources of bias that could compromise the validity of trials (Fig. 2). Certainty of evidence ranged from very low to high using the GRADE methodology. Downgrading was due to the high level of heterogeneity across studies (i.e. I 2 above 55%), lack of information on masking of outcome assessors and attrition (online Supplementary File 1).

Fig. 2 . Risk of bias in included studies.

Narrative synthesis and meta-analyses

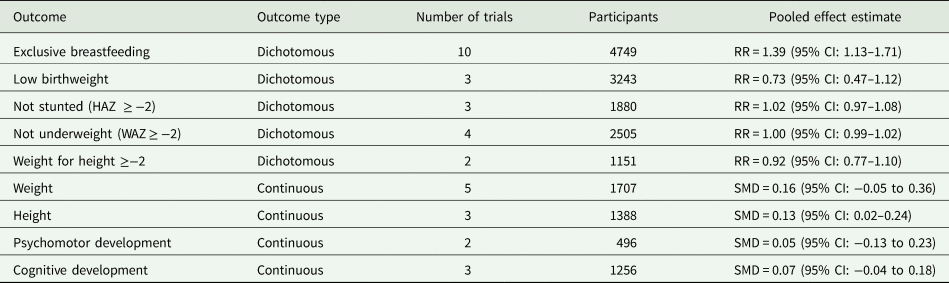

A summary of the results from meta-analyses is provided in Table 3. Growth indicators: the earliest growth indicator, low birth weight, was reported in four publications representing three trials. Findings were inconclusive as one trial reported a lower prevalence of low birth weight in infants of mothers in the intervention v. control (Bastani et al., Reference Bastani, Hidarnia, Montgomery, Aguilar-Vafaei and Kazemnejad2006), while others found marginal (Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b) or no difference in the prevalence of low birth weight between groups (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Farnot, Barros, Victora, Langer and Belizan1992) (online Supplementary File 2).

Table 3. Summary of quantitative synthesis

Standardised measures of weight-for-age and height-for-age were evaluated in five trials. Three trials reported weight- or height-for-age on a continuous scale (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla, Tabana, Afonso, De Sa, D'Souza, Joshi, Korgaonkar, Krishna, Price, Rahman and Patel2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Nisar, Tabana, Ain, Bibi, Bilal, Bibi, Liaqat, Sharif, Zulfiqar, Fuhr, Price, Patel and Rahman2019). The observed effect of the intervention on greater height-for-age in the trial by Rahman and colleagues (2008) was nullified after adjusting for baseline covariates at 6- and 12-months. However, the pooled effect of three trials of the Thinking Healthy Program found a small effect of the intervention on greater height-for-age at 6 months (SMD = 0.13, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.02–0.24; online Supplementary File 3). Two additional trials measured weight on a continuous scale (Mohd Shukri et al., Reference Mohd Shukri, Wells, Eaton, Mukhtar, Petelin, Jenko-Praznikar and Fewtrell2019; Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020), and when combined with the three Thinking Health Program trials, we did not find an effect of these interventions on child weight (online Supplementary File 4).

Several publications transformed height-for-age and weight-for-age into a binary variable indicating whether a child was stunted or underweight (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015). Le Roux et al. (Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013) found that infants in the home visit intervention group were less likely to be stunted at 6-months, but found no between-group differences for underweight. Tomlinson and colleagues found that infants of depressed mothers in the intervention group were comparable to infants of non-depressed mothers under intervention and control conditions in terms of height-for-age; whereas, infants of depressed mothers under control conditions had lower height-for-age at 6-months. Weight-for-age did not differ by condition or maternal depression (Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015). At 18-months, there was no difference in the odds of stunting between intervention conditions among children of mothers with elevated symptoms of antenatal depression, yet the odds of being underweight were greater under control conditions (Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Scheffler and Le Roux2018). In the same trial, weight-for-height findings were complex: children of depressed mothers under intervention conditions were at WHO recommended weight-for-height scores (i.e. weight-for-height z-score = 0), but children of non-depressed mothers (intervention and control conditions) and children of depressed mothers under control conditions, were above WHO recommended weight-for-height scores (i.e. weight-for-height z-score > 0). The authors suggest that these findings can be explained by the intervention children being taller and less likely to be stunted, whereas children of depressed mothers under control conditions were shorter and similar in weight to children of depressed mothers under intervention conditions and children of non-depressed mothers under intervention and control conditions (Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Harwood, Le Roux, O'Connor and WOrthman2015). A separate trial that identified a main effect of the intervention on the odds of not being underweight (odds ratio (OR) = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.01–1.16), but no intervention effects on stunting from birth to 12-months (OR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.90–1.08) (Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a). Meta-analyses of categorical growth indicators did not find evidence of pooled intervention effects for being underweight, being stunted, and severe acute malnutrition – weight-for-height (online Supplementary Files 5–7).

Child health status: newborn health status was reported in seven trials and was operationalised as a function of growth and development indicators (Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b), infant/foetal complications (Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020), incidence of illness (Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montogomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019), Apgar score (Karamoozian and Askarizadeh, Reference Karamoozian and Askarizadeh2015; Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020), duration of hospitalisation (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Linhares, Padovani and Martinez2009) or neonatal mortality (Tripathy et al., Reference Tripathy, Nair, Barnett, Mahapatra, Borghi, Rath, Rath, Gope, Mahto, Sinha, Lakshminarayana, Patel, Pagel, Prost and Costello2010). Heterogeneity in outcome definitions precluded meta-analysis of child health status, but independent studies reported positive intervention effects on Apgar scores and neonatal mortality (Tripathy et al., Reference Tripathy, Nair, Barnett, Mahapatra, Borghi, Rath, Rath, Gope, Mahto, Sinha, Lakshminarayana, Patel, Pagel, Prost and Costello2010; Karamoozian and Askarizadeh, Reference Karamoozian and Askarizadeh2015). In contrast, one study found that psychological intervention was associated with more hospital and NICU days, mixed findings related to postpartum complications (Rajeswari and SanjeevaReddy, Reference Rajeswari and Sanjeevareddy2020), and no effect of interventions on the incidence of child illness (Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Linhares, Padovani and Martinez2009; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montogomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019).

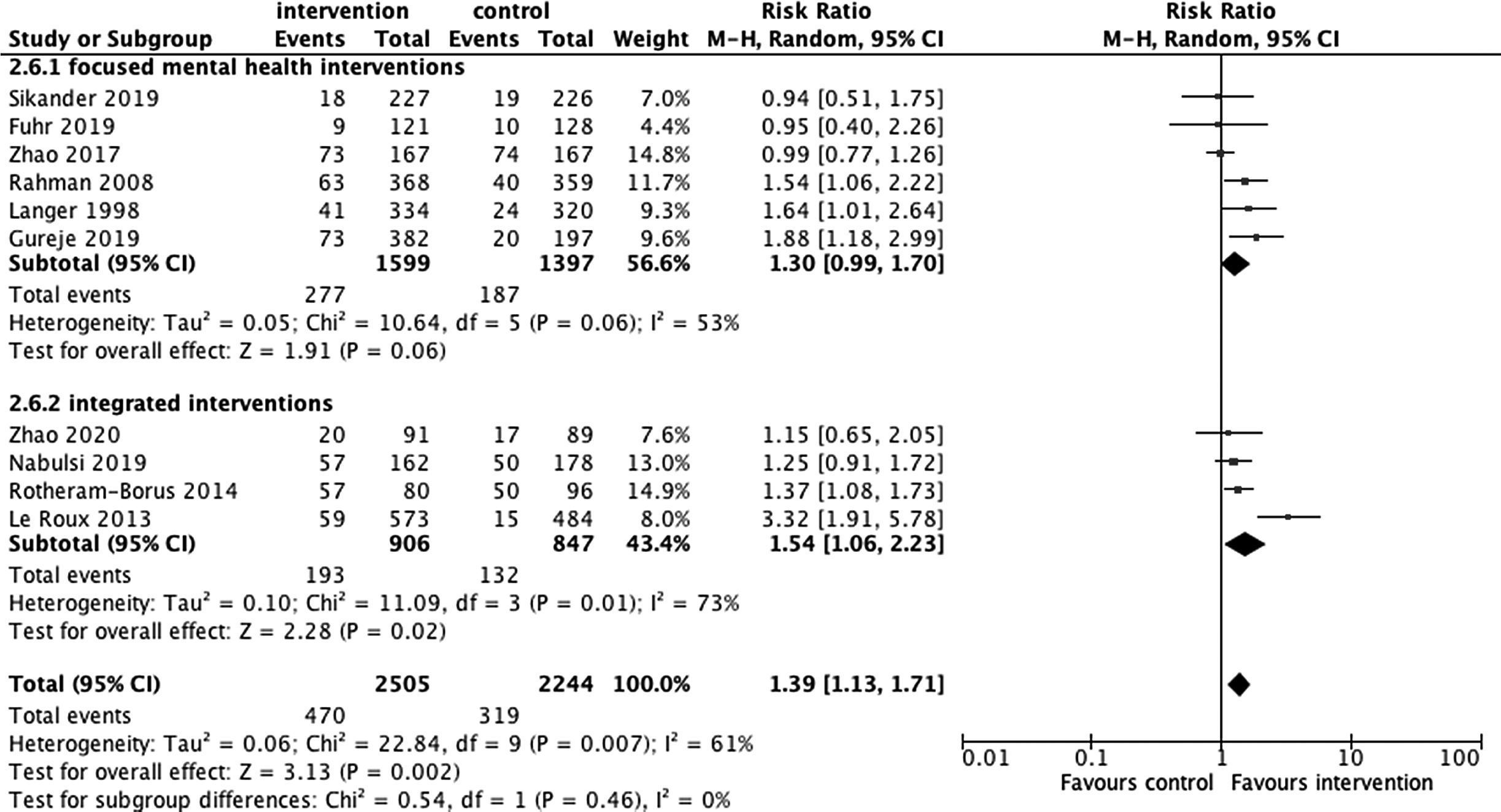

Breastfeeding: ten trials included breastfeeding as an outcome. Results of the meta-analysis (n = 4749) including data across ten comparisons indicated a sizeable overall impact in favour of intervention with moderate certainty according to the GRADE assessment: RR of 1.39, 95% CI: 1.13–1.71, NNT = 22.00, 95% CI: 15.00–40.90) (Langer et al., Reference Langer, Campero, Garcia and Reynoso1998; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Munro-Kramer, Shi, Wang and Luo2017; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla, Tabana, Afonso, De Sa, D'Souza, Joshi, Korgaonkar, Krishna, Price, Rahman and Patel2019; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montogomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019; Nabulsi et al., Reference Nabulsi, Tamim, Shamsedine, Charaffeddine, Yehya, Kabakian-Khasholian, Masri, Nasser, Ayash and Ghanem2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Nisar, Tabana, Ain, Bibi, Bilal, Bibi, Liaqat, Sharif, Zulfiqar, Fuhr, Price, Patel and Rahman2019; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lin, Wang and Bao2020) (Fig. 3). Heterogeneity was significant (I 2 = 61%) indicating substantial variation between interventions in their impacts on the outcome. Sub-group analyses revealed slightly larger effect sizes for integrated MMH interventions compared to focused MMH interventions, however uncertainty was high in these subgroups.

Fig. 3 . Exclusive breastfeeding by type of mental health intervention (focused v. integrated).

Maternal–child relationship outcomes: one trial focusing on the mother–child relationship found more secure attachment of infants of mothers under the intervention relative to the control conditions (74 v. 63%), which was driven by a higher probability of avoidant attachment in control infants (19 v. 11%) (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Tomlinson, Swartz, Landman, Molteno, Stein, McPherson and Murray2009). In contrast, results from another trial found the proportion of infants with ‘normal bonding’ similar under intervention (98%) and control (98.9%) conditions (Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a).

Developmental outcomes: seven publications representing four trials evaluated one or more of the following domains of child development: cognitive development, language development, socio-emotional development, motor development, physical development, aggressive and prosocial behaviour and executive functioning. When evaluating development as one broad outcome, there were no differences between infants of mothers under the intervention relative to the control conditions in the short- and long-term (Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Richter, Van Heerden, Van Rooyen, Tomlinson, Harwood, Comulada and Stein2014a; Rotheram-Borus et al., Reference Rotheram-Borus, Tomlinson, Le Roux, Harwood, Comulada, O'Connor, Weiss and Worthman2014b; Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015). Results focusing on specific domains of child development were mixed (Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Arteche, Stein and Tomlinson2015). Cognitive and psychomotor developments were the only indicators measured in more than one study. We did not observe an impact of MMH interventions on cognitive development (3 trials, 1256 participants, SMD = 0.07, 95% CI: −0.04 to 0.18, I 2 = 0%; online Supplementary File 8) (Maselko et al., Reference Maselko, Sikander, Bhalotra, Bangash, Ganga, Mukherjee, Egger, Franz, Bibi, Liaqat, Kanwal, Abbasi, Noor, Ameen and Rahman2015; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Arteche, Stein and Tomlinson2015; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Scheffler and Le Roux2018). Similarly, there was no effect of MMH interventions on psychomotor development (2 trials, 496 participants, SMD = 0.05, 95% CI: −0.13 to 0.23, I 2 = 0%; online Supplementary File 9) (Aracena et al., Reference Aracena, Krause, Perez, Mendez, Salvatierra, Soto, Pantoja, Navarro and Salinas2009; Le Roux et al., Reference Le Roux, Tomlinson, Harwood, O'Connor, Worthman, Mbewu, Stewart, Harley, Swendeman, Comulada, Weiss and Rotheram-Borus2013).

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to summarise existing experimental knowledge regarding the impact of MMH interventions on child-related outcomes. We identified 21 RCTs reporting on more than 28 000 participants. All trials focused on common mental disorders and most were conducted in middle-income countries.

The most commonly included outcome across these trials was exclusive breastfeeding. A recent meta-analysis found breastfeeding to be protective against child infections and malocclusion, associated with higher intelligence, and probable reductions in overweight and diabetes (Victora et al., Reference Victora, Bahl, Barros, Franca, Horton, Krasevec, Murch, Sankar, Walker and Rollins2016). Nevertheless, only 37% of children under 6-months are exclusively breastfed in LMICs (Victora et al., Reference Victora, Bahl, Barros, Franca, Horton, Krasevec, Murch, Sankar, Walker and Rollins2016). In our study, meta-analysis of ten comparisons with a combined number of 4749 women showed that with intervention 39% more children are exclusively breastfed than under control conditions.

Given the varied nature of the interventions, it is challenging to single out the unique influence of the MMH components on improved rates of exclusive breastfeeding. However, one broad observation supports the contribution that MMH components can make in improving rates of exclusive breastfeeding. Future studies can be improved in two ways to clarify the impact of mental health components on exclusive breastfeeding. First, trials could be designed specifically so that mediation analyses can be conducted to assess whether improvements in MMH are in turn associated with exclusive breastfeeding. Second, head-to-head comparisons of interventions with and without a mental health component would be helpful to estimate the additional contribution of MMH components in integrated interventions.

Meta-analyses on other outcomes did not identify sizeable benefits of intervention and there was high heterogeneity between studies. These meta-analyses were limited by fewer available publications relative to the exclusive breastfeeding meta-analysis and should be interpreted with caution. There was a significant pooled effect of intervention on child height, but the effect size was small and only incorporated findings from three trials. There were trends favouring intervention for cognitive and psychomotor development, low birth weight, weight-for-age and height-for-age, but these did not reach statistical significance. It is possible that MMH interventions may have impacts on particular development domains, but not on broad indicators of child development. Similarly, MMH interventions may have impacts on particular growth indicators at specific developmental stages.

Before discussing implications of this systematic review and meta-analysis, we note the strengths and limitations of the existing literature. Overall, few trials included in this systematic review showed high risk of bias. Attrition and lack of masking were the greatest sources of potential bias. We presented conservative intention-to-treat analyses, but attrition introduced significant uncertainty in estimates. A substantive limitation to the generalisability of this review is that all interventions were focused on common mental disorder. It would be helpful for future studies to also evaluate whether interventions for other mental health outcomes (e.g. psychosis) are associated with improvements in child-related outcomes. Additionally, only one trial was conducted in a low-income country. Scaling of interventions may be particularly challenging in such settings, so further studies assessing impacts in low-income countries would be useful. Finally, there was substantial variation in how outcomes were defined and assessed, which limited the possibility to conduct meta-analyses for some outcomes.

Results from this review should be considered in light of several limitations in the review process. First, we included trials with diverse populations, who may respond differently to MMH interventions. Second, we included child outcomes that were reported across different studies, but did not prespecify primary v. secondary outcome measures, increasing the risk for selective reporting. However, we attempted to report on all available outcomes, without focusing only on those that were included in statistical re-analysis. The data used for our meta-analysis were primarily extracted from unadjusted results (means, standard deviations for continuous outcomes; n, percentage for binary outcomes), which in few instances resulted in marginally different measures of associations compared to adjusted models reported in the original trial publications. However, restriction of our searches to RCTs should reduce concerns of confounding and selection bias and thus these differences in outcome-specific inferences are not expected to result in substantial bias in our meta-analyses. Third, we did not specify sub-group analyses a priori as we were not sure which different intervention types had been studied and our review protocol was not pre-registered. While we aimed to report on the complete set of studies, outcomes and interventions that met our eligibility criteria, it is possible that not having published the study protocol prior to conducting the review may have introduced meta-bias. It is also possible that due to publication bias, our review does not reflect a fully representative synthesis of the evidence on the effect of MMH interventions on child development outcomes (Bender et al., Reference Bender, Friede, Koch, Kuss, Sclattmann, Scwarzer and Skipka2018). To mitigate this potential for publication bias, we searched eight non-academic databases to include unpublished literature meeting our eligibility criteria.

Notwithstanding these limitations, results of this systematic review and meta-analysis are promising and have implications for policy and practice. We identified a sizeable number of RCTs that evaluated the impact of MMH interventions on child-related outcomes in LMICs. Whereas impacts of these interventions on most child outcomes were uncertain, we identified a promising sizeable impact of MMH interventions on rates of exclusive breastfeeding, an outcome of vital public health importance globally. Evidence from this review further supports the importance of improving MMH, which has similarly been recommended by the WHO, as a strategy to further the critical effort to improve child health in LMICs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000864

Data

Data extracted from included studies for the narrative review and meta-analysis are available online: https://osf.io/qwdet/.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Anne Diehl, Huan He, Daniel Hostetler, Emily Kravinsky, Adaobi Nwabuo, Limbika Senganimalunje, Diana Rayes and Masoumeh Dejman for their assistance with data collection and extraction.

Author contributions

WAT and MCG developed the protocol. WAT and MCG developed and performed the search strategy. MCG and MEL screened titles and abstracts. WAT, MCG, MEL, MP and CB reviewed full texts and assessed study eligibility. MCG, MEL and MP assessed risk of bias and credibility of evidence. MP performed the meta-analysis and quantitative synthesis. WAT, MCG, MEL, KLR, CB, MP, MT and CB all contributed to writing, reading and approving this paper. The corresponding author, WAT, attests that all authors meet authorship criteria and no others meeting that criteria have been omitted.

Financial support

Funding for this review was provided by Action contre La Faim. MCG and MEL are funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (MCG: T32DA002792, T32MH096724; MEL: F31MH110155-02, T32MH103210). MT is supported by the National Research Foundation, South Africa and is Lead Investigator of the Centre of Excellence in Human Development, University Witwatersrand, South Africa.

Conflict of interest

Funding for the study described in this article was provided by Action contre La Faim. Dr Tol is also a member of the Scientific Advisory Committee to Action contre La Faim. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. The views expressed in the submitted article are not an official position of the institution or funder.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.