Introduction

For Mother's Day 2014, Natura – one of the leading Brazilian cosmetics companies – aired a TV commercial that depicted not only mothers of conventional families but also a same-sex couple with their children. It was a milestone in Brazilian advertising, inaugurating a new orientation in advertising which was soon emulated by other companies, and consolidating LGBTQ relevance in Brazilian marketing.Footnote 1 In June 2015, Pastor Silas Malafaia, a prominent right-wing figure and leader of an Evangelical church in Brazil, called for a boycott of Natura. He said it was one of the leading enterprises ‘promoting homosexuality’ and that ‘companies should think twice before engaging in such campaigns’.Footnote 2 That same year, Marco Feliciano, also a religious leader and federal deputy for the Partido Social Cristão (Social Christian Party, PSC), called for a boycott of another Brazilian cosmetics company, Boticário, because it was one of the sponsors of a TV soap opera in which two prominent Brazilian actresses portrayed a homosexual couple.Footnote 3

These calls reflect the rise of Brazil's ‘culture wars’, in which gender and sexuality have become the most important issues driving a recent wave of religiously motivated resentment.Footnote 4 The term ‘culture wars’ was most famously used by James Hunter as a means to convey the manifold cultural conflicts in the United States involving progressive and conservative social forces.Footnote 5 Hunter argues that, in the decades following the Second World War, cultural clashes changed from inter-confessional feuds (between Protestants, Catholics and Jews) to a cleavage between ‘orthodox’ and ‘progressive’ worldviews around issues such as family, art and education. Hunter's data, mostly from the 1980s, shows how entrenched this new divide was more than 30 years ago. US-style Evangelical Protestantism became noticeable in Brazil from the 1990s, creating similar divisions and conflicts around analogous issues. In this context, scholars have already demonstrated how these emergent culture wars reshaped Brazilian politics by mustering a loose but large conservative religious caucus at the national level.Footnote 6 The outrage against Natura and Boticário suggests, however, that this cultural conflict has spread beyond the political arena, also entering the economic domain.

How do companies cope with criticism when entering the growing LGBTQ market? This issue has become especially salient in the context of the recent neoconservative wave in Brazil. In this article we focus on the outcry in 2014–19 from Evangelical Christians against Natura and Boticário, the two largest Brazilian cosmetics companies. In a series of episodes involving social media, statements from religious leaders and accusations against companies’ commercials, a conservative offensive against the positive depiction of LGBTQ people and themes in advertising and marketing revealed a new front in the Brazilian culture wars unfolding in the terrain of markets and business. In line with their stated commitment to social causes and diversity, an awareness of LGBTQ inclusion – notably as a reaction to an active and experienced LGBTQ movement – was increasingly embraced by large Brazilian companies, with a consequent conservative backlash.Footnote 7 Against this background, we examine how corporate practices have been influenced by an interplay of progressive and conservative activism in Brazil. We look closely at companies’ specific activities, especially their advertising, marketing and corporate communication.

This case offers perspectives from Latin America on how a changing cultural and political landscape can affect economic agents. Thus, we aim to contribute to the scholarship on the intersection of economic sociology and sociology of social movements in Latin America and the Global South, focusing on contention in Brazil. While the central topic of these intersecting areas – the targeting of economic actors – has only recently begun to be explored for the Global North,Footnote 8 in Brazil such studies are even rarer, in spite of some inaugural work.Footnote 9

We also consider the growing strength of conservative contention. While movements and progressive activists have been studied, conservative activism has only recently attracted academic attention.Footnote 10 This form of activism is embedded in the conservative wave that has emerged in the last few decades, and its expressions vary around the globe: neoconservatism in the United States, populist parties in Europe, and the shift towards authoritarian-leaning governments and anti-pluralist politics in democratic states in Asia.Footnote 11 In Brazil, this wave is represented by the social and political rise of conservative religious groups and the election of Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right retired military officer, as president in 2018. Serving as one of the main sources of this conservative backlash against progressive corporate practices is the rapid expansion of Evangelical Protestantism in Brazil: practised by 5 per cent of the Brazilian population in 1970, the level has risen to over 22 per cent in 2010.Footnote 12 The emergent agenda of Evangelicals relates mostly to moral concerns. Among its most visible expressions are the denunciation of LGBTQ inclusion as ‘gender ideology’.Footnote 13 Evangelicals condemn the teaching of gender issues in schools, joining other right-wing movements advocating control over what they see as political ideology in the education system.

We found that overall, when faced with a negative reaction from conservative opinion, companies have persisted in their commitment to diversity in marketing and discourse. However, firms also employ elusive strategies, such as targeted communication, and less controversial forms of retail design, signalling compromises with conservative stakeholders and sections of the public. As a lesson for economic sociology, these findings suggest that corporate reaction to protest can be complex and vary across companies’ divisions and levels. They also shed light on an emergent question for the study of social movements in Latin America, namely the unfolding of the new conservative wave. We demonstrate that religiously driven boycotts have surfaced as a new repertoire of contention amongst conservative segments of society. Nevertheless, conservative groups have encountered limits in pushing forward their agenda when targeting corporations.

This article initially presents our theoretical motivations, followed by a description of the data and methods. We then describe the profiles of the two companies, Natura and Boticário, within the cosmetics sector in Brazil and their relations to progressive corporate attitudes. The following sections discuss the consolidation of the LGBTQ movement, and then the appearance of pink marketing in the cosmetics industry and the conservative backlash it sparked in Brazil. After this overview of the Brazilian context, we present some evidence regarding the extent to which firms have accommodated conservative criticism and whether they have withdrawn from LGBTQ marketing.

Studies of Criticism and Economic Change

Theoretically, we have been inspired by two schools of thought regarding political agency and its role in economic dynamics. Drawing on anglophone historical sociology of social movements – beginning with Charles TillyFootnote 14 – nascent research has highlighted the role of protest and dispute in the economy. One of the central insights from this research is that contention matters in markets: it impacts stock prices and profits while also prompting changes in human-resources management, marketing and firms’ political and legal activity.Footnote 15 Contention is also crucial in corporate and institutional change, as argued by Sarah Soule, for the rise of corporate social responsibility (CSR).Footnote 16

Echoing similar concerns, works in French pragmatic sociology and the economics of conventions explore the role of criticism in institutional and social transformation.Footnote 17 New forms of regulations and political realignments generated by conflicts around financial scandals and changes in the valuation of products, and consequently in firms’ practices due to the work of environmentally concerned consumers,Footnote 18 are key research areas that followed from these theoretical frameworks. Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello's book is a landmark work in this tradition.Footnote 19 The authors argue that a ‘new spirit’ of capitalism emerged after capitalism was subjected to the social and ‘artistic’ criticism of the 1960s and 1970s; this led to a shift in the corporate managerial world towards more creative and less hierarchical forms of work organisation based on ‘projects’ and ‘networks’.

These two bodies of literature – the anglophone historical sociology of social movements and French pragmatic sociology – have focused on the consequences of progressive contention for economic dynamics and long-term institutional change. However, in the case of the Brazilian cosmetics companies, conservative activism complicates the picture and raises the question of its own effects. While the French authors, Boltanski and Chiapello, and the anglophone Soule demonstrated that progressive contention rendered enterprises susceptible to broader concerns such as the self-fulfilment of managers, inclusion, social justice and the environment,Footnote 20 we ask if conservative reaction is capable of reversing progressive corporate awareness.

Because these scholars have focused on the effects of progressive criticism, their frameworks do not clearly specify what the outcomes of conservative criticism, such as anti-LGBTQ, would be. Following their insights, we can nevertheless infer some of its potential effects. Emphasising the normative dimension of social life, Boltanski and his fellow French pragmatists consider that social critique can be appeased, as its values are embodied in reformed institutions. These values must be universalisable in order for a durable agreement to be established between the parties in a dispute. Since the conservative and progressive positions seem to represent irreconcilable normative commitments, the dispute is likely to become a long-term controversy. As such, it may in certain contexts evolve into a compromise.Footnote 21 Alternatively, actors may employ elusive strategies and avoid reaching a definitive breaking point, in order to avert the disruptive consequences of open conflict or costly negotiation.Footnote 22 In turn, the theoretical approach that inspires Soule's work highlights the power relations involved in clashes between activists and companies.Footnote 23 Companies will primarily act following a cost/benefit logic, but activists may force them to act differently, when they successfully mobilise resources against corporate interests. From this perspective, if conservative groups yield sufficient power, companies would be forced to change their inclusive policies.

In summary, theories of criticism and economic change suggest that the observed results and consequences of contention against companies should express how strong conservative groups have become in Brazil in the last decades. Their success and failure should enlighten us as to how well organised and experienced they are for the cultural struggle in the economic realm, in contrast to other groups. They should also show to what extent firms perceive this contention as a threat to business as usual and, in the context of a culture war, how companies could circumvent criticism by means of compromises and strategies for deflecting ill will.

Before closing this section, we discuss some challenges and the specifics of studying companies’ professed progressive attitudes. In the context of the promise of CSR, a significant body of work addresses the question of whether companies really embrace socioenvironmental values or simply adhere to them strategically.Footnote 24 While we will not engage in this debate directly, we are aware that companies can instrumentalise their social and environmental commitment to pursue symbolic power or maximise shareholder value. Organisational purposes in the domain of social responsibility can have a contradictory and ambiguous nature. Although a critical issue, it does not alter the fact that activism and criticism can change companies’ behaviour – if only to continue business as usual. These shifts matter for a comprehensive understanding of how broader social trends relate to the economy.

In this article we focus on some of specific features of corporate inclusive practices while ignoring other concerns. We analyse whether Natura and Boticário have maintained or reversed LGBTQ-oriented marketing and advertisement when confronted with criticism from conservative groups. Two points should be made on the choice of this particular research subject. First, while other transformations, such as the rise of CSR, encourage actions of social and economic inclusion, changes in marketing and advertisement address some of its symbolic aspects. Though less concrete, this symbolic dimension should not be understated: ‘advertising does not claim to depict life as it is but as it should be – life and lives worth emulating. Thus, to be ignored by advertising is a powerful form of symbolic annihilation, but to be represented in the commercial universe is an important milestone on the road to full citizenship in the republic of consumerism.’Footnote 25

Second, we acknowledge that the inclusion of minorities in general advertising is often shrouded in scepticism. Activists and scholars emphasise that inclusion in ‘consumerism’ is not enough.Footnote 26 Economic citizenship does not guarantee full citizenship rights for LGBTQ groups. Also, companies do resort to ‘pinkwashing’: the adoption of LGBTQ-inclusive discourse and marketing as a diversion from bad corporate practices such as large-scale lay-offs, tax avoidance and poor working conditions. Still, we believe LGBTQ-oriented marketing can be considered evidence of a progressive shift in the corporate world as it advances ‘recognition’ and acceptance of LGBTQ people.Footnote 27 Despite its contradictions and ambiguities, LGBTQ-oriented marketing constitutes a significant part of companies’ strategies, revealing discernible and testable aspects of the relationship between firms and activism.

The Study Design

Natura and Boticário were chosen not only because of their roles in marketing controversies but also because they are fully Brazilian companies. Scholars of comparative political economy point out the heterogeneity of the Latin American, and particularly Brazilian, business landscape. Brazilian firms – usually as part of a larger business group – coexist with an exceptional number of foreign companies.Footnote 28 Whereas the increasing pervasiveness of multinationals started in the 1950s, a period when Brazilian manufacturing companies also flourished, in the 1990s a second incursion of foreign multinationals rested largely on the acquisition of these existing Brazilian firms. These acquisitions occurred in the wake of neoliberal ascendance, when Brazil deindustrialised as a consequence of a drastic shift in its economic-policy regime.Footnote 29 All in all, the persistence and growth of Brazilian mid-tech industrial firms is far from usual in this context. Thus, Natura and Boticário offer a rare insight into the business rationale in modern economic sectors shaped entirely in Brazil, without the support or interference of foreign parent companies.

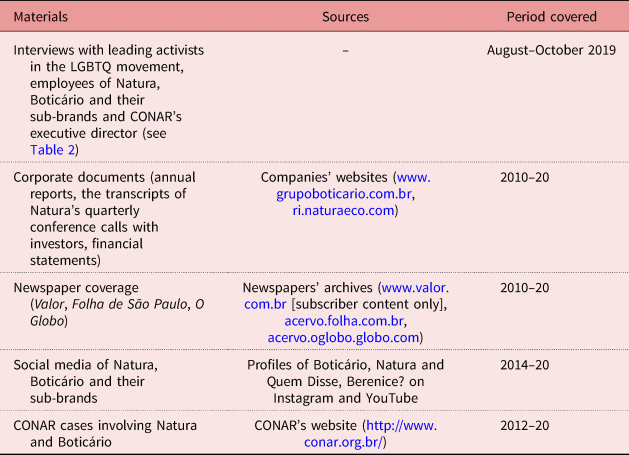

We have drawn on materials from different sources concerning conservative activism, social movements and companies, comprising the years 2010–20 (Table 1). These materials were addressed through a mixed-methods approach, aiming for complementarity.Footnote 30 Qualitative and quantitative data were used to tackle overlapping but different aspects of companies’ responses to criticism; we thereby pursued a multi-layered understanding of the interplay between activism and firms’ behaviour.

Table 1. Materials and Sources

Table 2. Interviewees

Twelve interviews were conducted, covering leading activists in the Brazilian LGBTQ movement, employees of the Brazilian cosmetics companies Natura, Boticário and their sub-brands, the executive director of the Conselho Nacional de Autorregulamentação Publicitária (National Council for Advertising Self-Regulation, CONAR), and an analyst with an investment fund familiar with Natura (Table 2). Participants were approached using purposive and snowballing strategies, and interviewed between August and October 2019 using a VoIP app. The choice of interviewees reflects different standpoints and offers complementary perspectives on LGBTQ marketing, conservative criticism and companies’ reaction.

We also examined several publicly available corporate documents, such as Boticário's and Natura's annual reports, and annual reports and press releases from the Associação Brasileira da Indústria de Higiene Pessoal, Perfumaria e Cosméticos (Brazilian Association of the Personal Care, Perfumery and Cosmetics Industry, ABIHPEC). Financial statements were analysed to provide a quantitative assessment of companies’ budgets. We complemented this material with reports and documents from Instituto Natura and the Fundação Grupo Boticário de Proteção à Natureza (Boticário Group Foundation for the Protection of Nature).

For further insight into the top management's perspective, we analysed the transcripts of Natura's quarterly conference with investors. As Boticário remains unlisted, there is less material available on the internet and no equivalent of Natura's conference calls with shareholders. In Natura's conference calls with investors, chief officers present quarterly results; these are followed by questions from representatives of major shareholders – mostly banks. We assembled a corpus of 39 texts from the available transcripts of conference calls on Natura's investor-relations website (see Table 2) between 2009 and 2019. In addition to reading transcripts from quarters where conservative reaction against TV commercials were notable, we examined the whole corpus using Prospéro, a computer program for textual analysis.Footnote 31 We searched for nouns, verbs and expressions related to LGBTQ, conservatism and political contention in the whole corpus.

As advertisement controversies can be complex and scattered across different social arenas, CONAR stands out as a particular venue where contrasting expressions are gathered and controversies can be further examined. We gave close consideration to complaints lodged with CONAR about cosmetics companies – particularly Natura and Boticário – between 2012 and 2020. CONAR is an NGO created in 1978 and funded by the advertising industry to implement the Código Brasileiro de Autorregulamentação Publicitária (Brazilian Advertising Self-regulation Code).Footnote 32 Its role is to adjudicate in cases arising from complaints by civil society, firms or the Council itself. For each case, the Council appoints one of its members as rapporteur, in charge of assessing the complaints. She issues an opinion to the plenum, which then rules upon it. Decisions are binding and firms are obliged to alter or withdraw advertising according to the Council's ruling.

Finally, newspaper coverage and social media – especially those of Natura, Boticário and their subsidiaries – provided crucial general information. Newspaper articles were taken from Valor, a business daily, and Folha de São Paulo and O Globo, two major generalist newspapers. We searched for articles on the controversies surrounding Natura and Boticário in the newspapers’ online article archives for the years 2010–20. The companies’ profiles in social media – Instagram and YouTube – offered further information on marketing campaigns and the reactions they triggered. We reviewed posts and videos published since 2014, when LGBTQ first appeared in their campaigns. Overall, newspaper and social media material provided an overview of the actors involved and allowed us to trace the main episodes in which conservatives protested against companies. Along with the interviews and the academic literature, these materials lay the groundwork for the next three sections, which present the companies, the LGBTQ movement and the conservative backlash.

The Cosmetics Industry in Brazil and Progressive Practices

In recent decades the cosmetics industry has emerged as one of the most promising business sectors in Brazil.Footnote 33 The domestic cosmetics market is responsible for 6.9 per cent of world sales (fourth only to the United States, China and Japan).Footnote 34 The bulk of the domestic cosmetics market is dominated by British-Dutch transnational Unilever and Brazil's Grupo Boticário and Natura & Co. Brazilian firms are not only gaining prominence regionally, with a consistent presence in Latin American markets, but also tapping into global markets, with Natura acquiring The Body Shop and Avon franchises in the last few years.

Boticário – the Portuguese word is cognate with ‘apothecary’ – started in 1977 in a pharmacy compounding business in Curitiba, the capital of the southern Brazilian state of Paraná. One of its founding partners, Miguel Krigsner, was a biochemist who ventured into the production of beauty products based on natural ingredients. Originally a secondary activity to the pharmacy, perfumery and cosmetics quickly became the company's main business in the early 1980s. Boticário is now the third-largest company in the sector, employing over 10,000 people, including at sales points. Boticário relies on franchising as a marketing strategy for its successful expansion, and had over 4,000 franchise sales points in 2019. Embodying its product-diversification strategy, in 2012 Grupo Boticário launched an open-minded and youthful sub-brand called ‘Quem Disse, Berenice?’, in contrast to its parent company's more formal image. (The name, which translates as ‘Who says so, Berenice?’, recalls the Brazilian expression meaning ‘Who says that I have to do that?’) Eventually, in 2014, Quem Disse, Berenice? set the tone for the marketing of the entire company: according to an employee, Boticário realised they had lost their relevance among newer, younger audiences, and the Quem Disse, Berenice? team took over Boticário's marketing effort.Footnote 35 Boticário is also prominent in environmental issues. In 1990, Krigsner led what was then a pioneering initiative among the Brazilian business community and created the Fundação Grupo Boticário de Proteção à Natureza, funded by a portion of the company's net revenue.Footnote 36 CSR has also been a concern since the 2000s and, from 2015, the company has emphasised the importance of diversity issues in statements by its Chief Executive Officer and annual sustainability report.

Natura was founded in 1969 in São Paulo by Luiz Seabra, an economist who had previously managed a cosmetics laboratory. Inspired by Avon's marketing model, he steered the company toward direct sales in 1974, closing its flagship store. Natura is now the largest cosmetics company in Brazil. Unlike Boticário, which remains unlisted, Natura went public in 2004. Amidst the crises that struck the Brazilian economy and the cosmetics industry in the mid-2010s, Natura embarked upon an internationalisation effort and bought the foreign brands The Body Shop and Aesop in 2017, and Avon in 2020. In total, the corporate group had 18,000 employees in 2018. Natura alone has a huge direct-selling network with 1.7 million ‘consultants’, the company's term for its sellers, mostly women in informal work, not covered by labour regulations or social security regulations.Footnote 37 The executive behind the expansion of sales in the 1970s was Guilherme Leal, a leading figure in environmental and corporate social responsibility. Cofounder of Instituto Ethos – which pioneered CSR support for companies in Brazil – in the early 1990s, soon after the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro,Footnote 38 he was also a running mate of the Green Party presidential candidate in the 2014 elections. In the Brazilian business arena, Natura was among the avant-garde of CSR.Footnote 39 Its annual reports have included diversity initiatives since the early 2000s. Natura's Política de Valorização da Diversidade (Diversity Promotion Policy), drafted in 2016, expressly outlines the company's commitment to greater inclusion of the LGBTQ community.Footnote 40

In the 2010s, as ascending mid-tech firms in a developing country, both Natura and Boticário promoted socially and environmentally responsible initiatives coupled with inclusive marketing visuals. With those marketing campaigns, they mirrored the practices of same-level companies worldwide. Some drivers of this convergence have been described by Paul DiMaggio and Walter Powell in their well-known paper on how similar behaviours in organisations can spring from ‘coercive, mimetic, and normative sources’.Footnote 41 Whereas there was no apparent coercive (or encouraging) pressure from the government – not even during the centre–left administration of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party, 2003–16) – LGBTQ activists have pushed forward their demands not only on the corporate world but on other spheres as well (as discussed in the following sections). Initiatives intensified as both companies expanded abroad, suggesting also a dimension of competitive and mimetic adherence to these practices so as to align with other firms at international level. Regarding normative pressures, professional features and leadership traits may also have favoured those initiatives. As noted above, Natura's Leal was an early adopter of CSR in Brazil, and Boticário's Krigsner is also a long-time patron of environmental causes. Their progressive profiles appear to reflect similar liberal stances among the employees in their communication and marketing teams.Footnote 42 This collection of factors offers some potential insight into the companies’ marketing stance. Underlying this emulation of international competition and growing normative commitment of firms is the emergence of a new generation of managers in Brazil, of which Leal is a member.Footnote 43 Alert to new developments in the United States and Europe, these managers introduced the concept of CSR and socioenvironmental awareness to the Brazilian business community in the 1990s. Though also belonging to the Brazilian business elite, they have increasingly stood as challengers of traditional business views, sharing a fairly progressive view of the corporation's role in society.

LGBTQ Activism and the Emergence of Pink Marketing

LGBTQ activists and movements, broadly defined as lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender, have advocated for equal rights since the early twentieth century. The ‘Q’, for ‘queer’, was added to the LGBT acronym after the term was reclaimed in the early 1990s, as it encompasses identities and practices which transcend binaries of sex and gender (for example, asexual, intersex, gender-neutral). In Brazil, the LGBTQ movement gained relevance in late 1970s, influenced by international networks, with roots in the political fervour that marked the end of the military dictatorship (1964–85).Footnote 44 Activists who were becoming politically involved in the 1990s entered a field marked by the country's slow transition from military to civilian rule, and dense networks of religious, community, labour and partisan activism. Those emergent forms of LGBTQ activism converged with mobilisations of other groups such as Black Brazilians, women and Indigenous peoples.Footnote 45

The LGBTQ movement in Brazil has grown considerably since the 1990s, and now consists of several significant groups. Its vigour is evidenced by substantial contributions to the expansion of community rights.Footnote 46 Same-sex marriage has been legal in Brazil since a ruling of the Supremo Tribunal Federal (Supreme Court) in 2011 and a decision by the Conselho Nacional de Justiça (National Justice Council) in 2013.Footnote 47 LGBTQ characters have been portrayed in acclaimed soap operas in unprejudiced ways. Surveys also show broad acceptance, with around two-thirds of the Brazilian population claiming to support LGBTQ rights.Footnote 48 Brazilian activism has spread beyond the country's borders and contributed to the global push for gay rights, with the passing of the ‘Draft Resolution on Human Rights and Sexual Orientation’ at the United Nations Commission on Human Rights in 2003.Footnote 49

In both Luis Inácio Lula da Silva's (2003–10) and Dilma Rousseff's (2011–14) administrations, the ministries of education, culture and health and the then recently strengthened Secretaria de Direitos Humanos (Secretariat of Human Rights) met several of the demands of LGBTQ activists. The Secretariat, particularly, favoured a social rights agenda focused on vulnerable groups, including LGBTQ.Footnote 50 In the promising institutional environment under centre–left governments, a Conselho Nacional de Combate à Discriminação LGBT (National Council to Fight LGBT Discrimination) was created in 2010 and three LGBT public policy conferences took place between 2008 and 2016, whose reports gathered together several proposals to advance LGBTQ rights.Footnote 51 These political circumstances facilitated the adoption of LGBTQ discourse in Brazilian society in general and an acceptance of the growing LGBTQ presence in business and marketing.

The effectiveness of activists and social movements goes hand in hand with the formation of LGBTQ consumer groups.Footnote 52 While the question of LGBTQ rights became a compelling topic of political debate in the 2000s, the expanding niche market also brought the debate to the economic sphere. ‘Pink capitalism’, ‘pink money’ and ‘the pink economy’ are terms that capture the overt admission of gays/lesbians to the products market. Major segments of the pink economy include travel, entertainment and cosmetics. From the companies’ perspective, meeting LGBTQ-specific demands also meant a realignment of corporate policy with evolving social values. For the LGBTQ movement, in turn, it is not obvious whether the pink economy represents genuine progress.Footnote 53 As an LGBTQ activist and scholar based in São Paulo told us, since the 1990s, and more overtly in the 2000s, recognition through marketing campaigns has meant only a particular form of inclusion: market assimilation driven by profits from pink money.Footnote 54

The growing LGBTQ consumer market found a favourable reception in the firms’ targeting strategies. In marketing, price and quality strategies should be supplemented by consumer-centred concepts, based on the heterogeneity of demand.Footnote 55 Following such guidelines, Brazilian cosmetics firms have deployed marketing strategies focused on specific consumer groups like young people, older adults, men and environmentally conscious and socially engaged consumers.Footnote 56 Possibly the most relevant of these targeted groups is the LGBTQ community. LGBTQ purchasing power in Brazil was estimated to total US$107 billion in 2018, ahead of European countries such as Italy and Spain.Footnote 57 Targeting is an important strategy for both firms, as we observed in our interviews. According to one interviewee, a brand manager at Natura, companies differentiate their product lines and marketing to deal with diversity themes: ‘We have some product ranges that deal with the theme [of diversity] more properly; the main one is “Faces”.’Footnote 58 These initiatives can be understood within branding practices, a common method in the modern corporate world for attaching social or cultural meaning to a commodity as a means to make it more personally relevant to consumers.Footnote 59

In Brazil, advertising campaigns have become a key dimension of companies’ endeavours in the pink market.Footnote 60 As mentioned in the Introduction, Natura's advertising campaign in 2014 addressing the LGBTQ public was a turning point. It was closely followed by Boticário's TV campaign in 2015 for the ‘Dia dos Namorados’, or ‘Lovers’ Day’, depicting LGBTQ couples meeting for dates and exchanging gifts. (The Brazilian equivalent of Saint Valentine's Day is celebrated on 12 June.) The competition was influenced by their example, and soon Unilever too produced advertising campaigns depicting same-sex couples. In the following years the cosmetics industry became the bulwark of pink marketing, as Natura and Boticário created other TV advertisements that depicted same-sex couples, especially on the Dia dos Namorados.

Other LGBTQ campaigns have been more social media-oriented. Boticário's Instagram account has 9.9 million followers and expresses a cautious stance, avoiding issues regarding sexuality. In contrast, the Instagram account of Quem Disse, Berenice? has become more assertive in its LGBTQ content; it has 3 million followers.Footnote 61 The company released a promotional image in January 2019 in which a female same-sex couple were kissing: it provoked thousands of comments, both positive and negative, and, despite sparking much discussion and many boycott threats in the following weeks, it was not withdrawn. A manager at Quem Disse, Berenice? reported that it was met with widespread support from other cosmetics companies’ social media.Footnote 62 This is suggestive of how the marketing and business communities, when challenged by conservative critique, may be supportive of progressive views, at least on the internet. In June 2019, during LGBTQ Pride Month, the social media of Quem Disse, Berenice? focused on telling stories of coming out, transsexuals’ experiences and family relations that roughly translated into assertions of respect, liberty and acceptance. Natura's social media are more cautious in depicting same-sex couples. They concentrate such portrayals in a specific product line, Faces, with only two posts of women kissing. Although overall highly accepted, several negative comments regarding the posts emerged on Natura's social media. Other campaigns portrayed same-sex female couples, and the ambivalent or polemic reaction was similar.

Repertoires of Mobilisation and the Rise of the Conservative (Evangelical) Backlash

As diversity marketing impacts on the sensibilities of conservative groups, the polemics often take the form of boycott calls against companies. Boycotts – consumers’ refusal to buy a company's product or service because the company takes a stand on ideological or economic values that is opposed to the consumer's personal opinions or beliefs – are one of the main historical forms of anticorporate action.Footnote 63 Their workings are limited not to inflicting economic losses, but also – and sometimes mainly – to causing symbolic harm, as brands’ reputations can be tarnished by boycott calls. In culture wars, where at least two parties confront each other, boycotts can be followed by their opposite: ‘buycotts’. These happen when a company's product or service is favoured by the opposing group, and therefore deliberately purchased, as a reaction to boycott calls.

Both conservative and progressive groups have used boycotts (or buycotts) as their predominant form of action against (or in support of) companies. The differences between the groups lie elsewhere, of course, in their contrasting attitudes towards social change. Following Hunter's characterisation,Footnote 64 conservative – or, in his terminology, ‘orthodox’ – groups rely on a transcendental and rigid moral framework, in which God or an avowed image of human nature provides the ultimate criteria for evaluating reality. For their part, progressive groups allow for the revision and modernisation of fundamental beliefs. Thus, tradition is reworked to reconcile with new circumstances. Given these underlying moral guidelines, the two camps have different motivations for engaging in public affairs. Conservatives have taken part in the public sphere most often in the form of countermobilisation against progressive movements.Footnote 65 Their boycotts also rarely involve mass mobilisations, but rather seek to build a strategic stance in the political sphere.Footnote 66

Conservative boycotts in the United States are suitable comparative instances, especially because Evangelicalism in Brazil derives from the intensive efforts of US missionaries.Footnote 67 In the United States, the repercussions of conservative boycotts have been noticeable since the 1980s. Facing boycott threats from religious groups, Pepsi pulled a TV commercial featuring pop singer Madonna in 1989 and cancelled their promotion of her world tour.Footnote 68 In 1994, furniture retailer IKEA was one of the first companies to air a commercial on US TV depicting a male gay couple. The commercial was heavily criticised by conservative groups, culminating in a bomb threat against a New York IKEA store that subsequently proved to be a hoax. In another exemplary case, the American Family Association (AFA) campaigned in 1996 against Disney Group's policies to extend insurance benefits to their LGBTQ employees’ partners. Later, the AFA campaigned against Ellen DeGeneres and her ABC television show, after she came out as lesbian.Footnote 69 Despite intense strife, these campaigns failed: IKEA did not withdraw the commercial, Disney maintained its gay-friendly policies and ABC continued to broadcast the DeGeneres show.

In Brazil, the conservative backlash against LGBTQ marketing and media visibility in general came comparatively late, in the 2010s. In another notable example, Rede Globo's soap opera Salve Jorge was boycotted in 2015 by Evangelicals for depicting a controversial saint who has origins in both African religions and Catholicism. African religions – such as Candomblé and Umbanda – suffer intense hostility from Evangelicals, as their holy figures and practices are deemed pagan or satanic. In addition to the influence of important religious leaders, these boycotts were also driven by clashes between TV networks. Owned by a prominent Evangelical pastor, Grupo Record – Globo's competitor in the mainstream TV business – actively called on its conservative audience to boycott Salve Jorge.Footnote 70 Soon after, the Evangelical caucus in Congress called on Evangelicals not to buy Natura's products for advertising in Babilônia, a soap opera with LGBTQ themes.Footnote 71

The political and cultural role of Evangelicals in the Brazilian conservative wave is considerable. Since the 1980s, religious congregations in Brazil have played a growing role in democratic politics. The rise of neo-Pentecostalism changed the competitive landscape for both the Catholic Church and non-Pentecostal Protestant leaders, leading to the ‘Pentecostalisation’ of both religious traditions, in the sense that they became more conservative.Footnote 72 Neo-Pentecostal churches began to expand in Brazil in the 1970s, attracting the public by offering healing rituals, performing exorcisms and promising spiritual solutions to family and financial problems.Footnote 73 The latter also introduced the ‘Prosperity Gospel’ to Brazil: this held out the prospect of inner-worldly salvation and favoured the emergence of affluent Evangelical groups. In the 2010s, Brazilian neo-Pentecostalism achieved considerable power, both through the sheer number of believers and places of worship, and in terms of its economic resources.

Worldwide, Evangelicals have become more involved in politics, and US Evangelicals have influenced their counterparts in Latin America when it comes to forging relationships with political parties, influencing lobbyists and fighting gay marriage.Footnote 74 The numerous neo-Pentecostal churches that emerged in Brazil during the 1990s and 2000s were particularly active against the overt depiction of same-sex couples in the media, forming the core of anti-corporate activism after 2014. The Evangelical community has elected many representatives to the Chamber of Deputies (the lower chamber of Brazil's National Congress). In 2019 they formed the nucleus of the caucus blocking LGBTQ rights and other progressive claims, with 90 members out of the total of 513 members of the federal Congress. These religious groups were a significant support base for the election of Jair Bolsonaro as president in 2018: he has repeatedly made derogatory comments about LGBTQ people during his political career. In the economic sphere, cosmetics companies have been one of the main targets of these groups’ activism in Brazil.

The Persistence of Diversity Marketing and Discourse

In this section we summarise what the materials we analysed reveal about Natura and Boticário's behaviour in the face of conservative criticism. The cases lodged with CONAR can serve as a first access point to the controversies surrounding LGBTQ-oriented advertisements. The Council's executive director reported how diversity themes are frequently the subject of advertisement battles, as citizens complain directly to CONAR when they feel offended by advertising of any kind. Complaints have become more frequent, as Brazilian advertisers are increasingly exploring themes that were once taboo.Footnote 75

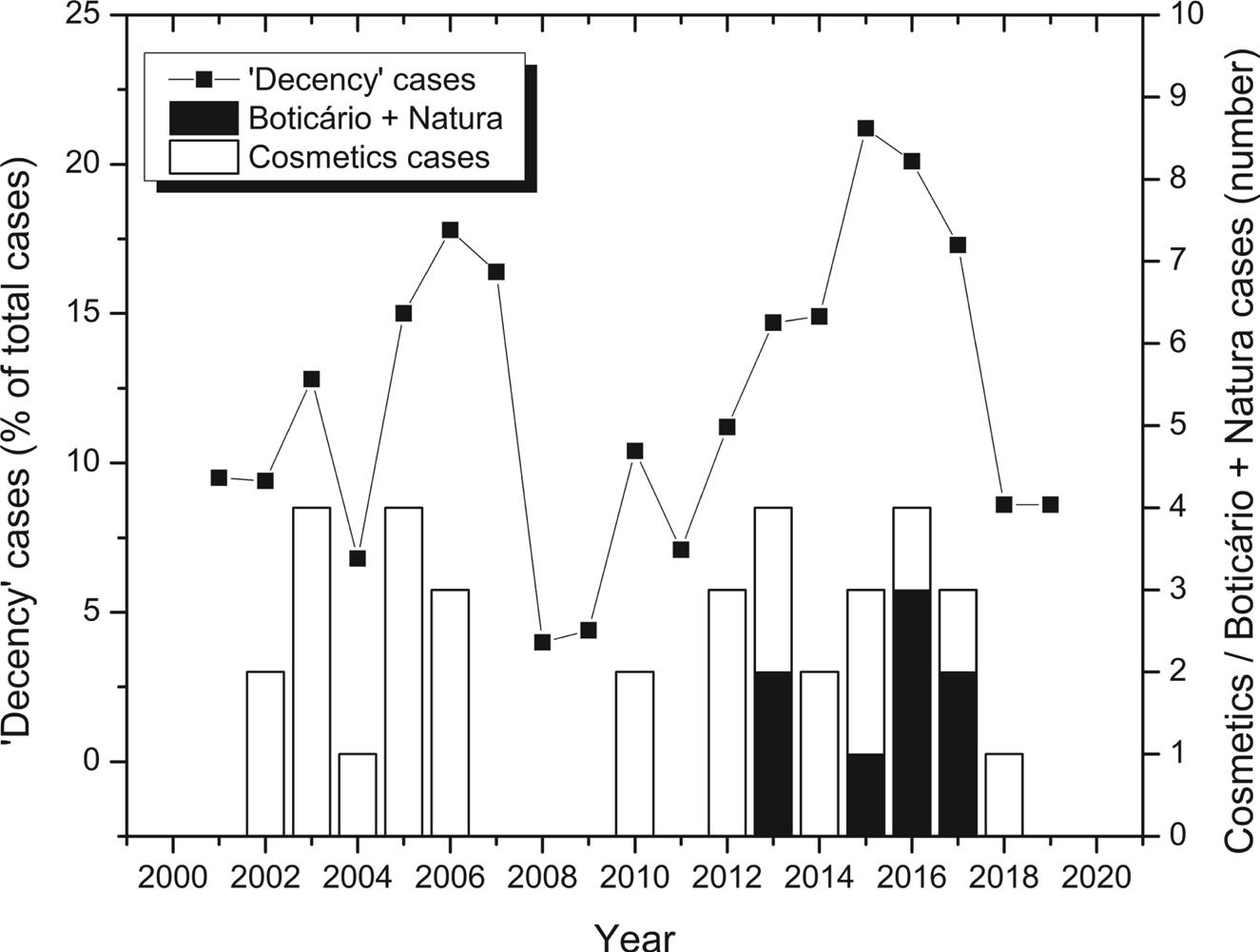

A look at CONAR's decisions over the last two decades offers some insights into trends in moral concerns and the targeting of cosmetics companies. Between 2001 and 2019, the annual number of cases it ruled on ranged from 241 to 448, with an average of 327. CONAR has 14 categories for the cases brought before it. Cases relating to inappropriate content in marketing are classified under ‘decency’. We counted all the cases in this class from 2001 to 2019, and specifically those involving cosmetics companies (see Figure 1). As cases classified under ‘decency’ originate mostly from consumer complaints, rather than from other companies or the Council itself, they may act as a barometer of this strand of contention over time. There are two peaks in cases concerning inappropriate content, one in 2005–7 and the other in 2013–17, separated by a quieter interval between 2008 and 2012. These peaks are accompanied by an increase in cases concerning cosmetics companies. While in 2005–7 complaints against these companies focused on Unilever bands, they started to include Boticário and Natura in 2013–17, as these companies ventured into less-conventional themes in their marketing campaigns. This parallels a qualitative change in the motivations of complaints by consumers. Before 2013, complaints concentrated on obscenity depicted in national and local campaigns. Thereafter, they also included the conservative agenda against the depiction of non-traditional gender roles and family models.

Figure 1. CONAR cases, 2001–19

Source: Authors' elaboration from data provided by CONAR.

We then closely analysed 20 cosmetics-industry-related complaints between 2012 and 2020, when the conservative groups gained new prominence. Overall, CONAR proved unreceptive to conservative contention against LGBTQ in marketing. All the rulings on cases related to moral outrage against advertisements were favourable to the companies involved. The same was true with regard to the eight complaints analysed against Boticário and Natura specifically. One particular case concerning Boticário is revealing of CONAR's stance with regard to conservative criticism. An advertisement for the Dia dos Namorados in 2015 depicting heterosexual and same-sex couples exchanging gifts sparked a strong reaction, receiving about 500 letters of complaint (apparently not coordinated) from viewers. After news of the criticism made it to the press, some 500 letters of support arrived at CONAR. Eventually CONAR ruled in favour of Boticário, arguing that the TV commercial portrayed the reality of contemporary society and that ‘advertising should not omit that reality’.Footnote 76

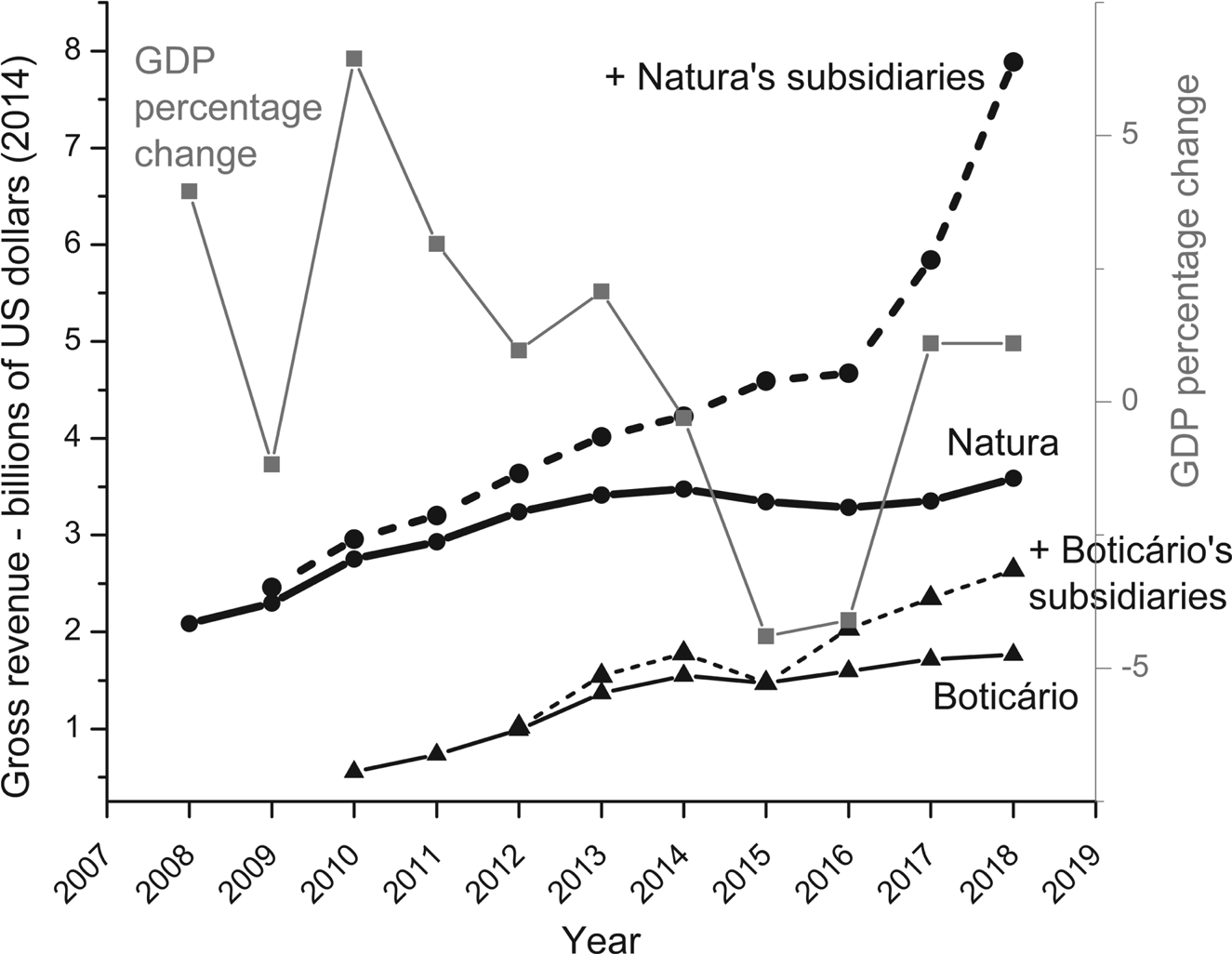

Though it is not easy to assess the impacts of consumer campaigns on companies’ economic indicators,Footnote 77 the financial performance of Boticário and Natura lends itself to some general remarks on how it has been affected both by the conservative wave and by economic crisis in Brazil. Figure 2 shows the gross revenue of each company and their subsidiaries, accompanied by the growth rate of the Brazilian economy 2008–18. Economic growth in Brazil plunged between 2013 and 2017 and has remained stagnant in the years since. In this crisis, the decrease in income was the sharpest ever experienced and the recovery to pre-crisis income levels has been very slow.Footnote 78 Both companies therefore experienced a downturn after 2014; the increase in their gross revenues came mostly from subsidiaries. In Natura's case, international acquisitions translated into increasing revenues that originated from foreign markets after the mid-2010s. This turbulent economic juncture coincides with the starting point of marketing campaigns depicting same-sex couples. More sophisticated statistical analysis would be required to measure the isolated net effects of protests and economic downturn.Footnote 79 However, we can speculate that the contribution of conservative resentment against companies to the drop in their revenue is minor, if any, in comparison with the impact of the recession of the mid-2010s.

Figure 2. Natura's and Boticário's gross revenue and Brazilian GDP growth

Source: Authors' elaboration from Boticário's and Natura's annual reports and data provided by Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, IBGE).

The companies’ public documents reinforce the perception that conservative criticism did not affect their policies. We examined Natura's annual reports (2001–18) and Boticário's annual sustainability reports (2013–18). We looked at their diversity policies, and at possible concessions in response to conservative activism and the general conservative political climate in Brazil after 2016. Overall, the companies state that they expanded their inclusivity policies. While diversity in terms of gender equality and ethnic anti-discrimination were already established, specific measures concerning the LGBTQ community first appeared in Natura's 2017 report and in Boticário's 2018 report, as an expansion of earlier policies.

As they convey the companies’ carefully cultivated brand images, these reports should be read with caution. A different glimpse into the concerns of top management and shareholders can be found in Natura's quarterly conference calls. Their transcripts reveal a different emphasis, as they very rarely focus on social, environmental and diversity issues. As for conservative activism, neither in the detailed reading nor in the textual analysis with Prospéro could we detect mentions of pressure from consumer groups. This suggests that, when it comes to overarching strategic planning and decision-making, companies do not consider the new conservative activism to be a major issue. The themes that appeared most frequently in these documents suggest a focus on typical business issues such as sales growth, employees and productivity, discussed against the background of Brazilian and foreign markets. Regarding factors that hinder business, participants in the conference calls exclusively highlight economic matters: the number of working days in the quarter, exchange rate effects on imported inputs, operational difficulties in new distribution centres, and changing market structure due to more intense competition.

Thus, a first batch of evidence suggests that the companies have persisted in diversity marketing and discourse. A noticeable aspect of the new activism against Brazilian companies since 2014 is that, although it has caused an uproar on social media and a considerable commotion in the public sphere, its impact in terms of boycott calls remains unclear. Activists themselves perceive consumer boycotts to be of limited effectiveness. Those leading both LGBTQ and conservative groups endeavour to establish boycotts of companies but have generally failed to mobilise their constituencies in large numbers, which they attribute to their own inexperience.Footnote 80 Although Evangelical political activism is backed by the growth of Evangelicals’ representation in Brazil's lower house of Congress,Footnote 81 their boycott attempts are often short-lived. ‘It does not work on account of the extremists. I used to joke that it works conversely as an advertisement for the product’, said the founder of a LGBTQ NGO, in existence since the 1990s.Footnote 82 Boycotts also seem not to be a part of the LGBTQ repertoire. ‘There is no boycott culture; no use thinking of that as a justification to try and mobilise our community.’Footnote 83 Moreover, a scholar and LGBTQ activist reports how ‘boycotts do not have much effect. They encounter a persistent problem we have with generating consumer awareness. The boycott culture is not yet well established, so I think that often only a few organised progressive circles answer this type of call. In turn, the movement ends up promoting other forms of consumption incentives for companies that support diversity policies.’Footnote 84

From the perspective of shareholders and senior management, the conservative reaction to the companies’ increased diversity efforts in marketing seems of little consequence. Firms’ financial documents, trade associations reports, Natura's quarterly conference calls with investors, and an interviewee from an investment fund do not mention the boycotts in their assessments of firms’ performance.Footnote 85 In short, as the main cosmetics companies encountered a slowdown, corporate top leadership framed fluctuations in economic and market terms, focusing on the national economic outlook and management problems rather than on conservative protest.

Compromises with Conservative Stakeholders and Public

While the senior echelons of the businesses generally ignore conservative protest, other company levels do however acknowledge it in at least three ways. First, in some instances, protests and calls for boycotts force companies to react. In the CONAR cases, media and public-relations departments are required to respond to some of the social-media criticism and to mount a defence. According to an LGBTQ activist, ‘now all makeup companies have inclusive advertising, so choosing not to represent LGBTQ audiences would be counter to the industry's now common and expected general marketing practices’.Footnote 86 When called on to respond to criticism by conservative groups, companies rely on the rhetoric of diversity. Companies claim they do not focus on LGBTQ issues in particular but instead assimilate and display the diversity of Brazilian society as a whole. ‘All consumers are equal’, and ‘the brand does not raise a flag – diversity is natural’, said a communications coordinator at Boticário.Footnote 87 She added that the company takes into account the mood of Evangelical stakeholders and consumers, so it mostly uses generic wording such as ‘all forms of love’. She explained the company's reasoning thus: ‘It encompasses LGBTQ issues, but it is diluted, so it is harder to generate counter-arguments to it.’ The controversy is then shifted towards a case for inclusion versus an exclusionary enterprise model. This symbolic framing also has an economic aspect, as diversity means business: companies aspire to relate to different social groups for commercial reasons.Footnote 88

The consolidation of targeting illustrates a second impact of conservative activism. Boticário created the sub-brand Quem Disse, Berenice? in 2012, aiming at youth consumers and non-traditional audiences. Natura launched its own ‘broad-minded’ product line, Faces, targeting consumers with similar profiles. It provoked a negative reaction among ‘conservative segments of society, but the company maintained its position and monitored negative comments, which did not surpass 20 per cent’.Footnote 89 Marketing for these niche brands is much more casual, compared with the marketing efforts of their parent companies. The LGBTQ community is portrayed in advertisements and other promotional actions. Usually restricted to internet media, marketing for these brands causes much less controversy because of its limited reach and the intentional marketing to consumers’ preferences.

A third effect of conservative contention lies in intra-company relations. Companies have to adapt their practices to dampen criticism from religious stakeholders. Advertising raises tensions among religious employees: ‘The majority of Natura's sellers are Evangelical Christians, and in direct selling they do not accept [LGBTQ-friendly advertising]. When [Boticário's advertising] depicted a man exchanging a Lovers’ Day gift with another man, not only did franchisees reject it but the sellers also reacted very badly’, reports a manager at Natura.Footnote 90 Considerable pressure is placed on firms by both sellers and franchisees. In the development of marketing and visual merchandise, different sales conferences are held with franchisees according to their importance and size. The material proposed by the franchiser is screened and discussed. The heterogeneity of the franchisees’ backgrounds poses some challenges for diversity marketing. Several of the franchisees are Evangelicals who are opposed to more liberal visual merchandising in their stores. The retail-design division in Boticário considers the franchisees’ profile when creating visuals for sales points, to avoid arousing discontent, according to an interviewee from the visual design merchandising team.Footnote 91 Natura also experiences tensions in its intra-company diversity actions. A significant proportion of its ‘consultants’ in Brazil are Evangelical women aged 35–40, who react negatively to non-traditional gender roles being depicted in marketing.Footnote 92 The content of the company's new releases is selectively sent to sellers according to their profile, with more inclusive themes omitted in the case of those who are religious. Though external conservative contention has not led to noticeable change, certain measures are necessary to constrain internal contention and assure the compliance of religious stakeholders.

Concluding Remarks: The Economics of Conservative Practices

In the 2010s, as social and environmental concerns developed in the Brazilian corporate landscape, cosmetics companies were at the forefront of diversity marketing. Although their marketing efforts were in line with certain trends in Western societies, these companies’ actions made them participants in culture wars and they became targets of the growing contention of conservative religious groups. Calls for boycotts by religious leaders and politicians in churches and other arenas, complaints submitted to advertising regulatory bodies, and large-scale outcries on social media are the primary methods used by conservative activists against cosmetics companies. How have the companies reacted? Have they rethought their inclusive stance and renounced diversity marketing?

What stands out in the material we examined is the varied ramifications of conservative backlashes at different business levels. On the one hand, companies overall neither withdrew campaigns nor revised their general commitments after negative conservative reaction to the overt diversity marketing that began in 2014. Besides addressing diversity issues in its reports since the early 2000s, Natura took a major step in 2016 with its Diversity Promotion Policy, expressly addressing LGBTQ inclusion. Boticário also continues to stress its concern for diversity in reports and projects funded by the company and by the Boticário Foundation for the Protection of Nature. Both companies have announced that they are maintaining and expanding inclusive policies for LGBTQ workers, such as equivalent parental leave for LGBTQ families. Awareness of LGBTQ discrimination is also a requirement for team leaders, report the brand and communication employees interviewed.Footnote 93

Our evidence also suggests that shareholders and senior managers do not consider conservative disapproval as an immediate financial threat. Trade-association reports consider only macroeconomic factors affecting firms. In the transcripts of Natura's quarterly conference calls with investors between 2014 and 2019, the actions of conservative groups were never mentioned. One of our interviewees – an analyst of an investment fund based in London – asserted that she had never even heard about the boycott calls against the company.Footnote 94 Our research found that conventional economic variables were the central concern of shareholders, and were the driving factors influencing the companies’ management. Drawing on the theories we discussed earlier, these results indicate that the failure of conservative groups in changing corporate attitudes from above is illustrative of the limited power they are still able to wield in the arena of private politics. Protest against LGBTQ marketing has been consistently visible in the public arena, though not entirely effective. Conservative advocates seem not yet to have the experience and other resources for mobilising effective boycotts. In contrast to their successful rise in institutional politics, Evangelical groups have not yet achieved the same power when confronting companies.

However, at the operational level, conservative protest could not be ignored by sales managers and brand communication and marketing teams. As front-line staff dealing with consumers and stakeholders, these parts of the corporate structure are more responsive to the challenges posed by the Evangelical public. In line with theories on critique and lasting social controversies,Footnote 95 we also found that companies resort to compromises and avoid making tensions explicit. Firms employ evasive strategies, such as targeted communications and variations in retail design, signalling compromises with their conservative stakeholders and the general public.

Overall, these insights from Brazil show how the growing contention involving companies align with some main features of the ‘private politics’ in the United States. On the one hand, influenced by US Evangelicalism, the new role played by Evangelical churches and leaders in the struggles concerning gender in Brazil has begun to parallel that of their northern counterparts. The emergence of anti-LGBTQ activism has also occasioned a renewal of strategies adopted by conservative groups in Brazil. The repeated complaints filed at CONAR since 2015 – as well as the recurrence of boycott calls by pastors, and the contentious social-media engagement – suggest a new pattern in conservative activism.Footnote 96 Despite their limited economic effectiveness so far, religiously driven boycotts have stabilised this new repertoire of contention amongst conservative segments of the Brazilian public. Also, the emergence of this anti-LGBTQ wave and the adoption of tactics used by US conservatives should be understood partially as a response to the institutionalisation of LGBTQ and also to feminists’ recent demands in Brazil.Footnote 97

On the other hand, companies’ responses to conservative criticism and their manifest political orientations express their increasing commitment to international guidelines regarding social responsibility, diversity and sustainability. Embedded in CSR and corporate sustainability, the banner of diversity became established in companies as this new business culture was introduced in Brazil in the 1990s and 2000s. Studies indicate that these progressive stances are now fairly entrenched in various sectors of Brazilian business.Footnote 98 Natura in particular plays a very active part in the promotion of corporate sustainability on the part of the Brazilian business community. This backdrop helps to untangle the persistence of diversity in marketing in the face of conservative protest. Conservative claims pressing for the suppression of an LGBTQ presence in advertising clash with established principles of what would be considered good corporate governance.

The article also has theoretical implications for social-movement studies, since they have yet to theorise about the recent conservative activism, especially in Latin America. The evidence analysed in this article yields some insights. We identified a repertoire of strategies including boycott calls and complaints to CONAR. The less apparent opposition of stakeholders to LGBTQ marketing should also not be ignored, as intrafirm relations turn out to be a relevant arena for conservative attempts to block progressive initiatives. In spite of the conservatives’ lack of influence over general corporate attitudes, we have not yet perceived substantive changes in how they engage in contentious politics against companies. As a possible explanation for this, religious leaders’ calls for boycotts – although so far unsuccessful in impacting on companies economically – might offer them substantial symbolic and political gains. They can capitalise symbolically on the controversies. Though calls for boycotts are mostly ineffective, conservative religious leaders will resort to them as long as they can instrumentalise outrage and gain prestige in the eyes of their followers, since calls for boycotts via social media simplify and individualise political contention, requiring less commitment and fewer risks than traditional collective action.Footnote 99

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the interviewees for their generosity with their time, as well as the anonymous referees and JLAS's editors for a number of helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier version of this paper.