A Introduction

Information has always been a valuable as well as often sensitive asset for companies, states and citizens. In this sense, the link between data flowing across borders and the need to protect certain national interests is not entirely new and has been made before.Footnote 1 In particular during the late 1970s and the 1980s, as satellites, computers and software were profoundly changing the dynamics of communications, the trade-offs between allowing data to flow freely and asserting national jurisdiction became apparent. Echoing concerns of large multinational companies, some states worried that barriers to information flows might hinder economic activities and looked for mechanisms that could prevent the erection of such barriers. Non-binding solutions were found under the auspices of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in the form of principles that sought to balance the free flow of data with the national interests in the fields of privacy and security.Footnote 2 Yet, as the OECD itself points out, while this privacy framework endured, the situation then was profoundly different from the challenges in the realm of data governance we face today.Footnote 3 Ubiquitous digitization and the societal embeddedness of digital media have changed the volume, the intensity and, indeed, the nature of data flows.Footnote 4

The value of data, as well as the risks associated with data collection, data processing, data use and reuse, by both companies and governments, has dramatically changed. Beyond the flawed mantra of data being the ‘new oil’,Footnote 5 many studies point at the vast potential of data as a trigger for more efficient business operations, highly innovative solutions and better policy choices in all areas of societal life.Footnote 6 This transformative potential refers notably not only to ‘digital native’ areas, such as search or social networking, but also to brick-and-mortar or physical businesses, such as in manufacturing or logistics.Footnote 7 Overall, the implications of big data availability and analytics are multiple and some of them far reaching.Footnote 8

Recent enquiries have shown that not only the sheer amount of data and our dependence on it have exponentially increased but also the ways governments assert control over global data flows have changed.Footnote 9 Exerting jurisdiction over online matters beyond borders, as exemplified by the seminal French judgment in the Yahoo! case,Footnote 10 or Internet censorship, as practised by China and many other states,Footnote 11 are well-known examples of control. Yet, the new generation of Internet controls seeks to keep information from going out of a country, rather than stopping it from entering the sovereign state space. Governments increasingly ‘localize’ the data within their jurisdictions for a variety of reasons.Footnote 12 To be sure, this kind of erecting barriers to data flows impinges directly on trade and may endanger the realization of an innovative data economy. The provision of any digital products and services, cloud computing applications or, if we think in more future-oriented terms, the Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI), would not function under restrictions on the cross-border flow of data.Footnote 13 Data protectionism also comes at a certain cost for the countries adopting such measures.Footnote 14

At the same time, while it may often be true that higher levels of data protection will amount to a trade barrier, one cannot disregard the legitimate desire of countries to safeguard the fundamental rights of their citizens, public interests and values that matter for their constituencies. The impact of data collection and data use upon privacy protection in particular has been, in recent years, widely acknowledged by scholars and policymakers alike, as well as felt on the ground by regular users of digital products and services.Footnote 15 The risks have only been augmented in the era of big data, which presents certain distinct challenges to the protection of personal data and, by extension, to the protection of personal and family life.Footnote 16 Indeed, big data puts into question the very distinction between personal and non-personal data. On the one hand, it appears that one of the basic tools of data protection – that of anonymization, i.e. the process of removing identifiers to create anonymized datasets – is only of limited utility in a data-driven world, as in reality it is now rare for data generated by user activity to be completely and irreversibly anonymized.Footnote 17 On the other hand, big data enables the reidentification of data subjects by using and combining datasets of non-personal data, especially as data is persistent and can be retained indefinitely with the presently available technologies.Footnote 18

Big data also puts into question the fundamental elements of existing privacy protection laws, which often operate upon requirements of transparency and user’s consent.Footnote 19 Equally is data minimization as another core idea of privacy protection challenged, as firms are ‘hungry’ to get hold of more and more data.Footnote 20 These challenges have not been left unnoticed and have triggered the reform of data protection laws around the world, best exemplified by the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).Footnote 21 The reform initiatives are, however, not coherent and are culturally and socially embedded, reflecting societies’ deep understandings of constitutional values, relationships between citizens and the state, and the role of the market, to name but a few.Footnote 22 The striking divergences both in the perceptions and the regulation of privacy protection across nations and in particular between the fundamental rights approach of the EU and the more market-based, non-interventionist approach of the United StatesFootnote 23 have also meant that conventional forms of international cooperation and an agreement on shared standards of data protection have become highly unlikely.

Against this backdrop of a complex and contentious regulatory environment, data and cross-border data flows in particular have become one of the relatively new topics in global trade law discussions. Many questions have been raised in this context, for instance, whether and how do the existing trade rules apply to data flows? How should they be classified – as a good or a service, and if categorized as a service, under which services sector do they fall? How do we address new trade barriers, such as localization measures? How can we reconcile the free flow of data and countries’ privacy, national security and other public interest concerns? How do we ensure that trade law accommodates the data-driven economy and enables global trade for the benefit of all? Which are the appropriate forum and the decision-making processes for moving the global data economy agenda ahead? Many of these questions are still open and this chapter will not give satisfactory answers to them all. It will nonetheless provide valuable information and insights about the current state of global trade law that may help policymakers down the road. In this sense, the chapter has a two-prong objective: first, it seeks to clarify the interfaces between the data-driven economy and existing trade law; second, and more importantly, it traces the regulatory responses and the emerging legal design in preferential trade agreements (PTAs) with regard to digital trade and data flows in particular.

B WTO Law as Pre-Internet Law

While PTAs are in the spotlight of this chapter, the multilateral forum of the World Trade Organization (WTO) cannot be simply ignored – on the one hand, because it matters in its own right as a set of hard and enforceable rules on trade in goods, services and intellectual property (IP) protection, and on the other hand, because PTAs are in many senses only an addition to these rules. Politically speaking, the failings of the multilateral system on certain issues have prompted action on those issues in the preferential venues and this is particularly evident in the area of digital trade, as revealed later.

The WTO agreements, the fundamental basis of international trade law, were adopted during the Uruguay Round (1986–1994) and came into force in 1995.Footnote 24 Despite some adjustments – such as Information Technology Agreement (ITA),Footnote 25 its update in 2015 and the Trade Facilitation Agreement,Footnote 26 WTO law has not fundamentally changed and is still very much in its pre-Internet state.Footnote 27 One could, of course, argue that laws need not change with each and every new technological invention.Footnote 28 And indeed, the law of the WTO lends credence to such an argument because it is in many aspects, both in the substance and in the procedure, flexible and resilient. WTO law can be qualified as relatively ‘hard’, as it involves deep intervention in domestic regulatory regimes and can impose certain sanctions for breach of obligations.Footnote 29 It is furthermore based on powerful principles of non-discrimination, such as the most-favoured nation (MFN) and the national treatment (NT) obligations, that address all areas of economic life and could potentially tackle technological developments better than new made-to-measure regulatory acts. Many of the rules with regard to the application of the basic principles, with regard to standards, trade facilitation, subsidies and government procurement do also operate in a technologically neutral way.Footnote 30

Another advantage of WTO law that may be highlighted is that despite its high degree of legalization and focus on economic rules, it also permits some flexibilities. One of those relates to the so-called general exceptions clauses formulated under Article XX of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) 1994 and Article XIV of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), which allow WTO members to adopt measures that would otherwise violate their obligations and undertaken commitments, under the condition that these measures are not be applied in a manner that would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between countries where like conditions prevail, or a disguised restriction on trade. Particularly interesting for this chapter’s discussion on data flows are the possibilities that Article XIV of the GATS may open for maintaining existing and adopting new data restrictions. Article XIV enumerates different grounds as possible justifications and includes two specific categories that are of pertinence for our topic: (a) those relating to public order or public moralsFootnote 31 and (b) those that are necessary to secure compliance with laws or regulations,Footnote 32 including such on ‘the protection of the privacy of individuals in relation to the processing and dissemination of personal data and the protection of confidentiality of individual records and accounts’.Footnote 33 Under this provision, it has been argued, for instance, that the rules of the GDPR may be found to violate the obligations of the EU under the GATS.Footnote 34

Finally, in terms of evolution of norms, it can be maintained that the WTO possesses the advantage of a dispute settlement system that can foster legal evolution.Footnote 35 There is strong evidence in the WTO jurisprudence for both the capacity of the dispute settlement mechanism and for the relevance of the Internet in trade conflicts.Footnote 36 The US–GamblingFootnote 37 case is a great example in this context, as it confirmed that the GATS commitments apply to electronically supplied services and clarified key notions of services regulation, such as likeness and the scope of the ‘public morals/public order’ defence under Article XIV of the GATS.Footnote 38

Yet, plainly assuming that the WTO’s ‘adaptive governance’Footnote 39 works will be flawed. Indeed, there are many reasons to question it and be rather sceptic about the match between the existing WTO rules, their implementation and evolution, and contemporary digital trade. Apart from the current political context, which may prevent new and forward-looking rule-making,Footnote 40 there are important hindrances in applying the GATS in the digital environment. In particular, the GATS commitments are based upon old pre-Internet classifications of services and sectors, and these have become increasingly disconnected from trade practices.Footnote 41 For instance, as the WTO law presently stands, it is unclear whether previously unknown things, such as online games, should be categorized as goods or services (and thus whether the more binding GATT or the GATS apply). Provided that no physical medium is involved and one decides consequently to apply the GATS, the classification puzzle is by no means solved: Online games, for instance, as a new type of content platform, could be potentially fitted into the discrete categories of computer and related services, value-added telecommunications services, entertainment or audiovisual services. One may also be unsure when there is an electronic data flow intrinsic to the service whether to classify this flow separately or as part of the traditional services.Footnote 42 Classification is by no means trivial,Footnote 43 as each category implies a completely different set of duties and/or flexibilities for the WTO members. If online platforms and the services they offer were to be classified as computer services, for example, states would lack any wiggle-room whatsoever and would have to grant full access to foreign services and services suppliers and treat them as they treat domestic ones – because of the high level of existing commitments under the GATS of virtually all WTO members.Footnote 44 On the other hand, were online games classified as audiovisual services, most WTO members would have the policy space to maintain and adopt restrictive and discriminatory measures.Footnote 45 The evolutionary interpretation of schedules of specific commitments, as affirmed in China–Audiovisual Products, while a positive development, does not necessarily help much to achieve legal certainty in such situations.Footnote 46 Neither does the finding that the GATT and the GATS are not mutually exclusive.Footnote 47

The classification dilemma, as particularly critical for digital trade, is an illuminating example of this state of paralysis but by far not the only one. Many other issues, although discussed in the framework of the 1998 WTO Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, have been left without a solution or even a clarification.Footnote 48 For instance and as a minimum for advancing on the digital trade agenda, there is still no agreement on a permanent moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions and their content.Footnote 49 Against the backdrop of pre-Internet WTO law and despite the recent reinvigoration of the e-commerce negotiations under the 2019 Joint Statement Initiative,Footnote 50 many of the disruptive changes underpinning the data-driven economy have demanded regulatory solutions outside the ailing multilateral trade forum. States around the world have used in particular the venue of preferential trade agreements to fill in some of the gaps of the WTO framework, clarify its applications and beyond that, address the newer trade barriers and accommodate their striving for seamless digital trade. Quite naturally for developments in preferential trade, the framework that has emerged as a result and now regulates contemporary digital trade is not coherent. It is neither evenly spread across different countries, nor otherwise coordinated. Indeed, it is messy and fragmented both with regard to the substantive rules and the agreements’ membership.

In the following section, the chapter provides an overview of the developments in PTAs in the last two decades in the area of digital trade governance. The information stems from our own dataset TAPED: Trade Agreement Provisions on Electronic Commerce and Data,Footnote 51 which ran a detailed mapping and coding of all PTAs that include chapters, provisions, annexes or side documents that directly or indirectly regulate digital trade. In the subsequent section, we look at the new rules on free data flows and their design across different PTAs. We then analyze in more detail the most sophisticated template for digital trade rules that we have so far – that of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and some subsequent developments in the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA). In the final section, the chapter offers some thoughts about the current state of global digital trade law and the prospects of governing data flows.

C Evolution of Digital Trade Provisions in PTAs

I Overview and Some Emerging Trends

From the 347 PTAs agreed upon between 2000 and 2019 and reviewed in TAPED, 184 PTAs have provisions related to digital trade.Footnote 52 The largest number of provisions is found in e-commerce and intellectual property chapters; overall, the provisions remain however highly heterogeneous, addressing various issues ranging from customs duties and paperless trading to personal data protection and cybersecurity. The depth of the commitments and the extent of their binding nature can also vary significantly. For instance, if one looks at the top countries that have entered into PTAs with e-commerce provisions,Footnote 53 the European Union occupies the first place with Singapore, yet it is only in the very recent EU PTAsFootnote 54 that there is a dedicated chapter on e-commerce and some substantive provisions – beforehand e-commerce provisions were only few, part of the services chapters and limited to mere GATS-level commitments and cooperation pledges.Footnote 55

Putting the digital trade provisions along a chronological line, it is evident that the inclusion of provisions in PTAs referring explicitly to electronic commerce is not a recent phenomenon, although it has evolved significantly in the past eighteen years. The first e-commerce provision dates back to the 2000 Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between Jordan and the United States.Footnote 56 Almost at the same time, New Zealand and Singapore agreed upon the Closer Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), including an article on paperless trading. Two years later, the Australia–Singapore FTA (SAFTA), concluded on 17 February 2003, was the first PTA to have a dedicated chapter on e-commerce. At the moment of this writing, specific provisions applicable to e-commerce can be found in 109 PTAs, mostly in dedicated chapters (79) (for details, see Table 1.1). The last eight years have witnessed a significant increase in the number of agreements with digital trade provisions. As shown in Figure 1.1, digital trade provisions are, on average, included in more than 68 per cent of all PTAs that were concluded between 2010 and 2019 and despite the fall in agreed upon deals, more of them include digital trade provisions. The rise in the total number of PTAs with such norms is driven mainly by bilateral PTAs: 84 per cent of total PTAs since 2000 and involves both developed and developing countries.Footnote 57

Table 1.1. PTAs concluded with digital trade provisions per year (2000–2019)

| Year | Total PTAs | WTO notified | Digital trade provisions | E-commerce chapters | % PTAs with digital trade provisions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 20 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 10.00 |

| 2001 | 23 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 8.70 |

| 2002 | 26 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 16.00 |

| 2003 | 30 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 20.69 |

| 2004 | 29 | 14 | 6 | 6 | 21.43 |

| 2005 | 17 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 33.33 |

| 2006 | 26 | 13 | 7 | 6 | 31.82 |

| 2007 | 20 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 29.41 |

| 2008 | 24 | 27 | 9 | 6 | 40.91 |

| 2009 | 23 | 21 | 6 | 3 | 19.05 |

| 2010 | 14 | 18 | 5 | 3 | 50.00 |

| 2011 | 19 | 15 | 2 | 2 | 18.75 |

| 2012 | 8 | 20 | 3 | 3 | 33.33 |

| 2013 | 14 | 22 | 9 | 6 | 64.29 |

| 2014 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 88.89 |

| 2015 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 50.00 |

| 2016 | 11 | 14 | 7 | 5 | 71.43 |

| 2017 | 6 | 18 | 3 | 2 | 33.33 |

| 2018 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 100.00 |

| 2019 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 100.00 |

| Total | 347 | 272 | 109 | 79 |

Figure 1.1. Evolution of PTAs with digital trade provisions (2000–2019)

Among the PTAs with digital trade provisions, it is evident that the number and level of detail have also increased significantly over the years, as depicted in Figure 1.2. In 2019, 13 is the average number of provisions found in e-commerce chapters of PTAs, with an average number of 2,527 words (see Table 1.2).

Figure 1.2. PTAs with digital trade provisions: average number of articles and words

Table 1.2. PTAs with e-commerce chapters: average number of provisions and words (2000–2019)

| Year | Total PTAs | E-commerce chapters | Average number of articles | Average number of words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 20 | 2 | 1 | 91 |

| 2001 | 23 | 2 | 1 | 838 |

| 2002 | 25 | 4 | 4 | 168 |

| 2003 | 29 | 6 | 8 | 395 |

| 2004 | 28 | 6 | 6 | 606 |

| 2005 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 541 |

| 2006 | 22 | 7 | 6 | 801 |

| 2007 | 17 | 5 | 7 | 753 |

| 2008 | 22 | 9 | 7 | 606 |

| 2009 | 21 | 4 | 5 | 606 |

| 2010 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 313 |

| 2011 | 16 | 3 | 3 | 318 |

| 2012 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 233 |

| 2013 | 14 | 9 | 7 | 640 |

| 2014 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 1,073 |

| 2015 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 842 |

| 2016 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 1,390 |

| 2017 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 357 |

| 2018 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 1,697 |

| 2019 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 2,527 |

At the moment of writing, the Singapore–Australia Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA), updated in 2016, is the PTA in force with the highest number of provisions in an e-commerce chapter (19 in total), with 2,997 words. As of 2020, the USMCA would overtake SAFTA, as the current text of its Digital Trade chapter has also 19 articles but comprising 3,206 words. The new dedicated digital trade agreements go well beyond: the US–Japan Digital Trade Agreement has 5,346 words, and the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) between Chile, Singapore and New Zealand contains 10,887 words.

II Overview of Data-Related Rules in PTAs

One can in general speak of the relevance of trade rules for data and data flows, as they matter for data in at least three ways: (i) because they regulate the cross-border flow of data by regulating trade in goods and services as well as the protection of intellectual property; (ii) because they may install certain beyond the border rules that demand changes in domestic regulation – for example, with regard to procedures with electronic signatures or data protection; and (iii) finally, because trade law can limit the policy space that regulators have at home.Footnote 58 Thinking of the layered structure of the Internet, one also ought to take into account the entire set of global economic law rules that regulate infrastructure (e.g. rules with regard to communication networks and services, technical standards and IT hardware) and applications and content (such as software, computer and audiovisual services), so as to understand the existing regulatory environment with regard to data flows.Footnote 59 In addition to this generic trade law framework, whose rules are found both in WTO law and in the WTO-plus preferential agreements, the last decade has also witnessed the emergence of entirely new rules that explicitly regulate data flows. This section provides a brief overview of these rules.

It needs to be mentioned at the outset that there is no common agreement on a definition of data flows in PTAs, despite the wide-spread rhetoric around the term and its frequent use in reports and studies.Footnote 60 One of the first agreements that targets data – the South Korea–United States FTA – stressed in its Article 15.8 ‘the importance of the free flow of information in facilitating trade, and acknowledging the importance of protecting personal information’ and encouraged the Parties ‘to refrain from imposing or maintaining unnecessary barriers to electronic information flows across borders’.Footnote 61 Later agreements, such as the CPTPP and the USMCA, that are analyzed in more detail later, speak of ‘cross-border transfer of information by electronic means, including personal information’Footnote 62 and this has become the most common wording thus far. The new generation of EU FTAs have been cautious with regard to data and has only recently started to promote the inclusion of provisions on the ‘free flow of data’.Footnote 63 In essence, what can be maintained is that so far in the trade policy discourse and in the treaty language, there has not been any clear definition but despite the different terms used, there seems to be a tendency for a broad and encompassing definition of data flows (i) where there are bits of information (data) as part of the provision of a service or a product and (ii) where this data crosses borders, although the data flows do not neatly coincide with one commercial transaction and the provision of certain service may relate to multiple flows of data. In this sense, ‘[t]he geography of data flows is very different from the geography of trade flows’.Footnote 64 In addition, it may be noted that there has not been a distinction between different types of data – for instance, between personal and non-personal data, personal or company data or machine-to-machine data.Footnote 65 Yet, personal information is commonly included explicitly in the data-related provisions in PTAs,Footnote 66 whereby the potential clashes with domestic data protection regimes become evident.

Overall, specific data-related provisions are a relatively new phenomenon and can be found primarily in dedicated e-commerce chapters of PTAs and only in a handful of agreements. The rules refer to both the free cross-border flow of data and to banning or limiting data localization requirements. Provisions on the cross-border flow of data can be also found in chapters dealing with discrete services sectors, where data flows are inherent to the very definition of those servicesFootnote 67 – this is particularly valid for the telecommunications and the financial services sectors, as shown in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3. Overview of data-related provisions in PTAs

| Data flows | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Financial services | Telecommunication services | Data localization | |

| Soft commitments | 16 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Hard commitments | 12 | 70 | 64 | 11 |

| Total number of provisions | 28 | 70 | 65 | 12 |

1 Rules on Data Flows

If we look at the evolution of data flow provisions in PTAs, there has been a sea change over the years. Non-binding provisions on data flows appeared early. Already in the 2000 Jordan–US FTA, the Joint Statement on Electronic Commerce highlighted the ‘need to continue the free flow of information’, although it fell short of including an explicit provision in this regard. The first agreement having such a provision is the 2006 Taiwan–Nicaragua FTA, where as part of the cooperation activities, the parties affirmed the importance of working ‘to maintain cross-border flows of information as an essential element to promote a dynamic environment for electronic commerce’.Footnote 68 A similar wording is used in the 2008 Canada–Peru FTA,Footnote 69 the 2011 Korea–Peru FTA,Footnote 70 the 2011 Central America–Mexico FTA,Footnote 71 the 2013 Colombia–Costa Rica FTA,Footnote 72 the 2013 Canada–Honduras FTA,Footnote 73 the 2014 Canada–Korea FTA,Footnote 74 and the 2015 Japan–Mongolia FTA.Footnote 75 In the same line, in the 2010 Hong Kong–New Zealand FTA, the parties agreed to ensure that ‘their regulatory regimes support the free flow of services, including the development of innovative ways of developing services, using electronic means’.Footnote 76

A slightly stronger commitment can be found in the 2007 South Korea–US FTA, where the parties, after ‘recognizing the importance of the free flow of information in facilitating trade, and acknowledging the importance of protecting personal information’, stated that they ‘shall endeavor to refrain from imposing or maintaining unnecessary barriers to electronic information flows across borders’.Footnote 77 More recently and as typically for EU-led agreements, the parties have agreed to consider in future negotiations commitments related to cross-border flow of information. Such a clause is found in the 2018 EU–Japan EPA,Footnote 78 and in the modernization of the trade part of the EU–Mexico Global Agreement, currently under negotiation. In the latter two agreements, the parties commit to ‘reassess’ within three years of the entry into force of the agreement, the need for inclusion of provisions on the free flow of data into the treaty. This signals a repositioning of the EU on the issue of data flows, as well as EU’s wish to couple this in due time with the high data protection standards of the GDPR.Footnote 79 The EU follows this model of endorsing and protecting privacy as a fundamental right also in its proposals for digital trade chapters in the currently negotiated trade agreements with Australia, New Zealand and Tunisia,Footnote 80 as well as in the EU proposal for WTO rules on electronic commerce.Footnote 81

The first agreement having a binding provision on cross-border information flows is the 2014 Mexico–Panama FTA. According to this treaty, each party ‘shall allow its persons and the persons of the other Party to transmit electronic information, from and to its territory, when required by said person, in accordance with the applicable legislation on the protection of personal data and taking into consideration international practices’.Footnote 82 A much more detailed provision in this regard is found in the 2015 amended version of the Pacific Alliance Additional Protocol (PAAP),Footnote 83 which was modelled along the negotiated text of the 2016 Transpacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) and which has since then largely influenced all subsequent agreements having data flows provisions, such as notably the CPTPP and the USMCAFootnote 84 – both endorsing a strong protection of the free flow of data, as discussed in more detail later.

2 Data Localization

In recent years, some PTAs have started to include specific provisions on data localization, by either banning or limiting requirements of data localization or data use. An important difference with the data flows provisions analyzed earlier is that almost all the provisions on data localization found in PTAs are binding.Footnote 85 The first agreement with such rules is the 2015 Japan–Mongolia FTA. The provision stipulates that neither party shall require a service supplier of the other party, an investor of the other party, or an investment of an investor of the other party in the area of the former party, to use or locate computing facilities in that area as a condition for conducting its business.Footnote 86 Later the same year, the 2015 amended version of the PAAP, and as strongly influenced by the parallel TPP negotiations, included a similar provision on the use and location of computer facilities.Footnote 87 In 2016, the TPP included a clear ban on localization, which was then replicated in the CPTPP and the USMCA. The diffusion of these norms is clearly discernible in subsequent PTAs, such as the 2016 Chile–Uruguay FTAFootnote 88 and the 2016 Updated SAFTA,Footnote 89 which closely follow the CPTPP template.Footnote 90

3 Privacy and Data Protection

Eighty-one PTAs in our dataset include provisions on privacy, usually under the concept of ‘data protection’. Yet, the way personal data is protected varies considerably and can include a truly mixed bag of binding and non-binding provisions (see Table 1.4), which is symptomatic of the very different positions of the major actors and the inherent tensions between the regulatory goals of data innovation and data protection.Footnote 91

Table 1.4. Overview of privacy-related provisions in PTAs

| Total number of provisions | 89 |

| Soft commitments | 81 |

| Hard commitments | 8 |

Earlier agreements dealing with privacy issues consist of non-binding declarations. The 2000 Jordan–US FTA Joint Statement on Electronic Commerce, for instance, merely declares it necessary to ensure the effective protection of privacy regarding the processing of personal data on global information networks, yet states also that the means for privacy protection should be flexible and parties should encourage the private sector to develop and implement enforcement mechanisms, such as guidelines and verification and recourse methodologies, recommending the OECD Privacy Guidelines as an appropriate basis for policy development.Footnote 92 Similarly, the 2001 Canada–Costa Rica FTA includes a provision on privacy as part of the Joint Statement on Global Electronic Commerce, with both parties agreeing to share information on the functioning of their respective data protection regimes.Footnote 93 Later agreements include cooperation activities on enhancing the security of personal data in order to improve the level of protection of privacy in electronic communications and avoid obstacles to trade that requires transfer of personal data.Footnote 94 These activities include sharing information and experiences on regulations, laws and programmes on data protectionFootnote 95 or the overall domestic regime for the protection of personal information;Footnote 96 technical assistance in the form of exchange of information and experts;Footnote 97 research and training activities;Footnote 98 the establishment of joint programmes and projects;Footnote 99 maintaining a dialogue;Footnote 100 holding consultations on matters of data protection;Footnote 101 or in general, other cooperation mechanisms to ensure the protection of personal data.Footnote 102

PTAs have also dealt with personal data protection with reference to the adoption of domestic standards. While some merely recognize the importance or the benefits of protecting personal information online,Footnote 103 in several treaties parties specifically commit to adopt or maintain legislation or regulations that protect the personal data or privacy of users,Footnote 104 in relation to the processing and dissemination of data,Footnote 105 which may also include administrative measures,Footnote 106 or the adoption of non-discriminatory practices.Footnote 107 Few agreements include qualifications of this commitment, in the sense that each party shall take measures it deems appropriate and necessary considering the differences in existing systems for personal data protection,Footnote 108 that such measures shall be developed insofar as possible,Footnote 109 or that the parties have the right to define or regulate their own levels of protection of personal data in pursuit or furtherance of public policy objectives, and shall not be required to disclose confidential or sensitive information.Footnote 110 Some PTAs add that in the development of online personal data protection standards, each party shall take into account the existing international standards,Footnote 111 as well as criteria or guidelines of relevant international organizations or bodiesFootnote 112 – such as the APEC Privacy Framework and the OECD Guidelines on Transborder Flows of Personal Data (2013);Footnote 113 or to accord a high level of protection compatible with the highest international standards in order to ensure the confidence of e-commerce users.Footnote 114 In a handful of treaties, the parties commit to publish information on the personal data protection it provides to users of e-commerce,Footnote 115 including how individuals can pursue remedies and how businesses can comply with any legal requirements.Footnote 116 Certain agreements put special emphasis on the transfer of personal data, stipulating that it shall only take place if necessary for the implementation, by the competent authorities, of agreements concluded between the parties,Footnote 117 or that the countries need to have an adequate level of safeguards for the protection of personal data.Footnote 118 Some treaties add that the parties will encourage the use of encryption or security mechanisms for the personal information of the users, and their dissociation or anonymization, in cases where said data is provided to third parties.Footnote 119

PTA parties have also employed more binding options to protect personal information online. A first option is to consider the protection of the privacy of individuals in relation to the processing and dissemination of personal data and the protection of confidentiality of individual records as an exception in specific chapters of the agreement – such as for trade in services,Footnote 120 investment or establishment,Footnote 121 movement of persons,Footnote 122 telecommunicationsFootnote 123 and financial services.Footnote 124 Certain agreements, mostly EU led, even have special chapters on protection of personal data, including the principles of purpose limitation, data quality and proportionality, transparency, security, right to access, rectification and opposition, restrictions on onward transfers, and protection of sensitive data, as well as provisions on enforcement mechanisms, coherence with international commitments and cooperation between the parties in order to ensure an adequate level of protection of personal data.Footnote 125 The USMCA was the first US-led PTA to include such a provision that recognizes key principles of data protection.Footnote 126

A second option lets countries adopt appropriate measures to ensure the privacy protection while allowing the free movement of data, establishing a criterion of ‘equivalence’ – meaning that countries agree that personal data may be exchanged only where the receiving party undertakes to protect such data in at least an equivalent, similar or adequate way to the one applicable to that particular case in the party that supplies it. This has been largely the EU approach and to that end, parties commit to inform each other of their applicable rules and negotiate reciprocal general or specific agreements.Footnote 127

A third, less used, option leaves the development of rules on data protection to a treaty body. For example, in the 2012 Colombia–EU–Peru FTA (which also now includes Ecuador), the Trade Committee may establish a working group with the task of proposing guidelines to enable the signatory Andean Countries to become a ‘safe harbour’ for the protection of personal data. To this end, the working group shall adopt a cooperation agenda that defines priority aspects for accomplishing that purpose, especially regarding the respective homologation processes of data protection systems.Footnote 128

D Substantive Developments in Digital Trade Governance

As evident from the earlier overview, the regulatory environment for data flows has been substantially shaped by PTAs. The United States has played a key role in this process and has sought to endorse liberal rules in implementation of its ‘Digital Agenda’.Footnote 129 The agreements reached since 2002 with Australia, Bahrain, Chile, Morocco, Oman, Peru, Singapore, the Central American countries,Footnote 130 Panama, Colombia and South Korea, all contain critical WTO-plus (going above the WTO commitments) and WTO-extra (addressing issues not covered by the WTO) provisions in the broader field of digital trade. The emergent regulatory template on digital issues is not however limited to US agreements but has diffused and can be found in other FTAs, as evident from the earlier overview. Singapore, Australia, Japan and Colombia have been among the major drivers of this diffusion but as earlier mentioned, the issues covered and the levels of legalization may still vary substantially.Footnote 131

Key aspects of digital trade are typically addressed in (i) specifically dedicated e-commerce chapters; (ii) the chapters on cross-border supply of services; and (iii) the IP chapters. The electronic commerce chapters show by far the most substantial evolution over time – moving from less to more binding and from a mere compensation for the lack of progress in the WTO towards new (and partially innovative) digital trade rule-making. In the former sense, they have included a clear definition of ‘digital products’, which treats digital products delivered offline equally as those delivered online, so that technological neutrality is ensured. The chapters also recognize the applicability of WTO rules to electronic commerce, and establish a permanent moratorium on duties on the import or export of digital products by electronic transmission. Critically, the e-commerce chapters, especially those of US-led agreements, ensure both MFN and NT for digital products trade; discrimination is banned on the basis that digital products are ‘created, produced, published, stored, transmitted, contracted for, commissioned, or first made available on commercial terms outside the country’s territory’ or ‘whose author, performer, producer, developer, or distributor is a person of another party or a non-party’.Footnote 132

The e-commerce chapters do also include rules that go beyond the WTO and next to provisions on IT standards and interoperability, cybersecurity, electronic signatures and payments, paperless trading and e-government, the rules on data flows are the most illustrative example in this context. In the following two sections, we look more closely at the most advanced template for digital trade chapters endorsed by the CPTPP and slightly further developed by the USMCA, including also some remarks on the dedicated US–Japan Digital Trade Agreement.

I The CPTPP

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Transpacific Partnership (CPTPP; also known as the TPP11 or TPP 2.0)Footnote 133 was agreed upon in 2017 among eleven countries in the Pacific RimFootnote 134 and entered into force on 30 December 2018. The CPTPP represents 13.4 per cent of the the global gross domestic product, or $13.5 trillion, making it the third largest trade agreement after the North American Free Trade Agreement and the single market of the European Union.Footnote 135 Beyond the broader economic impact and, more importantly, for the discussion of this chapter, the CPTPP chapter on e-commerce created the most comprehensive template so far in the landscape of PTAs. It comprises eighteen articles and includes a number of new features.Footnote 136 It is fair to note that the e-commerce chapter of the CPTPP ‘survived’ the TPP negotiations in its entirety and without any change, so in a sense it still very much reflects the efforts of the United States in the domain of digital trade rule-making.

The CPTPP sought for the first time to explicitly restrict the use of data localization measures. Article 14.13(2) prohibits the parties from requiring a ‘covered person to use or locate computing facilities in that Party’s territory as a condition for conducting business in that territory’. The soft language from the US–South Korea FTA on free data flows is now framed as a hard rule: ‘[e]ach Party shall allow the cross-border transfer of information by electronic means, including personal information, when this activity is for the conduct of the business of a covered person’.Footnote 137 The rule has a broad scope and most data that is transferred over the Internet is likely to be covered, although the word ‘for’ may suggest the need for some causality between the flow of data and the business of the covered person.

Measures restricting digital flows or localization requirements under Article 14.13 CPTPP are permitted only if they do not amount to ‘arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on trade’ and do not ‘impose restrictions on transfers of information greater than are required to achieve the objective’.Footnote 138 These non-discriminatory conditions are similar to the test formulated by Article XIV GATS and Article XX GATT, which, as earlier noted, is meant to balance trade and non-trade interests. The CPTPP test differs from the WTO norms in one significant element: while there is a list of public policy objectives in the GATT and the GATS (such as public morals or public order), the CPTPP provides no such enumeration and simply speaks of a ‘legitimate public policy objective’.Footnote 139 This permits more regulatory autonomy for the CPTPP signatories. However, it also may lead to overall legal uncertainty. Further, it should be noted that the ban on localization measures is somewhat softened with regard to financial services and institutions.Footnote 140 An annex to the financial services chapter has a separate data transfer requirement, whereby certain restrictions on data flows may apply for the protection of privacy or confidentiality of individual records, or for prudential reasons.Footnote 141 Government procurement is also excluded.Footnote 142

Pursuant to Article 14.17, a CPTPP member may not require the transfer of, or access to, source code of software owned by a person of another party as a condition for the import, distribution, sale or use of such software, or of products containing such software, in its territory. The prohibition applies only to mass-market software or products containing such software.Footnote 143 This means that tailor-made products are excluded, as well as software used for critical infrastructure and those in commercially negotiated contracts.Footnote 144 The aim of this provision is to protect software companies and address their concerns about loss of IP or cracks in the security of their proprietary code.Footnote 145

These provisions illustrate an important development this chapter alluded to earlier, namely, the evolution of digital trade rules that go beyond the WTO and do not simply entail a clarification of existing bans on discrimination or more liberal commitments. It is also evident that the new rules do not merely set higher standards, as is generally anticipated from trade agreements; rather, they shape the regulatory space domestically and may even lower certain standards. A commitment to lower standards of protection is particularly palpable in the field of privacy and data protection.

Article 14.8(2) requires every CPTPP party to ‘adopt or maintain a legal framework that provides for the protection of the personal information of the users of electronic commerce’. No standards or benchmarks for the legal framework have been specified, except for a general requirement that CPTPP parties ‘take into account principles or guidelines of relevant international bodies’.Footnote 146 A footnote provides some clarification in saying that ‘[f]or greater certainty, a Party may comply with the obligation in this paragraph by adopting or maintaining measures such as a comprehensive privacy, personal information or personal data protection laws, sector-specific laws covering privacy, or laws that provide for the enforcement of voluntary undertakings by enterprises relating to privacy’.Footnote 147 Parties are also invited to promote compatibility between their data protection regimes.Footnote 148 Overall, there is a priority given to trade over privacy protection. This commitment had been pushed by the United States, which subscribes to a relatively weak and patchy protection of privacy. Timewise, this insertion can be linked to the Schrems I judgment of the Court of Justice of European Union (CJEU) that struck down the EU–US Safe Harbor Agreement.Footnote 149

The CPTPP contains also rules on consumer protection,Footnote 150 network neutralityFootnote 151 and spam control,Footnote 152 although these are fairly weak. The same is true for the newly introduced rules on cybersecurity under Article 14.16, which identifies a relatively limited scope of activities for cooperation, in situations of ‘malicious intrusions’ or ‘dissemination of malicious code’, and capacity-building of governmental bodies dealing with cybersecurity incidents.

II The USMCA

After the withdrawal of the United States from the TPP, there was some uncertainty as to the direction it will follow in its trade deals in general and on matters of digital trade in particular. The renegotiated NAFTA, now referred to as ‘United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement’ (USMCA), casts the doubts aside. The USMCA has a comprehensive electronic commerce chapter, which is now also properly titled ‘Digital Trade’ and follows all critical lines of the CPTPP in ensuring the free flow of data through a clear ban on data localization (Article 19.12), providing a non-discrimination treatment for digital products (Article 19.4) and a hard rule on free information flows (Article 19.11).

The USMCA appears particularly interesting in two aspects. The first one is that it keeps the clause on exceptions that permits the pursuit of certain non-economic objectives. Article 19.11 specifies, very much in the sense of the CPTPP, that parties can adopt or maintain a measure inconsistent with the free flow of data provision, if this is necessary to achieve a legitimate public policy objective, provided that the measure (a) is not applied in a manner which would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on trade; and (b) does not impose restrictions on transfers of information greater than are necessary to achieve the objective.Footnote 153 Furthermore and departing from the standard US approach, the USMCA signals abiding to some data protection principles. While Article 19.8 remains soft on prescribing domestic regimes on personal data protection, it recognizes principles and guidelines of relevant international bodies. Article 19.8 recognizes ‘the economic and social benefits of protecting the personal information of users of digital trade and the contribution that this makes to enhancing consumer confidence in digital trade’Footnote 154 and requires from the parties to ‘adopt or maintain a legal framework that provides for the protection of the personal information of the users of digital trade. In the development of its legal framework for the protection of personal information, each party should take into account principles and guidelines of relevant international bodies, such as the APEC Privacy Framework and the OECD Recommendation of the Council concerning Guidelines Governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data (2013)’.Footnote 155

The parties also recognize key principles of data protection, which include limitation on collection; choice; data quality; purpose specification; use limitation; security safeguards; transparency; individual participation; and accountability,Footnote 156 and aim to provide remedies for any violations.Footnote 157 This is interesting because it may go beyond what the United States has in its national laws on data protection and also because it reflects some of the principles the European Union has advocated in the domain of the protection of privacy. One can of course wonder whether this is a development caused by the ‘Brussels effect’, whereby the EU ‘exports’ its own domestic standards and they become global,Footnote 158 or whether we are seeing a shift in US privacy protection regimes as well.Footnote 159

Finally, three innovations of the USMCA may be mentioned. The first refers to the inclusion of ‘algorithms’, the meaning of which is ‘a defined sequence of steps, taken to solve a problem or obtain a result’Footnote 160 and has become part of the ban on requirements for the transfer or access to source code in Article 19.16. The second novum refers to the recognition of ‘interactive computer services’ as particularly vital to the growth of digital trade. Parties pledge in this sense not to ‘adopt or maintain measures that treat a supplier or user of an interactive computer service as an information content provider in determining liability for harms related to information stored, processed, transmitted, distributed, or made available by the service, except to the extent the supplier or user has, in whole or in part, created, or developed the information’.Footnote 161 This provision is important, as it seeks to clarify the liability of intermediaries and delineate it from the liability of host providers with regard to IP rights’ infringement.Footnote 162 It also secures the application of Section 230 of the US Communications Decency Act,Footnote 163 which insulates platforms from liability but has been recently under attack in many jurisdictions, including in the United States, in the face of fake news and other negative developments related to platforms’ power.Footnote 164 The third and rather liberal commitment of the USMCA parties regards open government data. This is truly innovative and very relevant in the domain of domestic regimes for data governance. In Article 19.18, the parties recognize that facilitating public access to and use of government information fosters economic and social development, competitiveness and innovation. ‘To the extent that a Party chooses to make government information, including data, available to the public, it shall endeavor to ensure that the information is in a machine-readable and open format and can be searched, retrieved, used, reused, and redistributed.’Footnote 165 There is in addition an endeavour to cooperate, so as to ‘expand access to and use of government information, including data, that the Party has made public, with a view to enhancing and generating business opportunities, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises’.Footnote 166

The US approach towards digital trade issues has been confirmed also by the recent US–Japan Digital Trade Agreement (DTA), signed on 7 October 2019, alongside the US–Japan Trade Agreement.Footnote 167 The DTA can be said to replicate almost all provisions of the USMCA and the CPTPP,Footnote 168 including the new USMCA rules on open government data,Footnote 169 source codeFootnote 170 and interactive computer servicesFootnote 171 but notably covering also financial and insurance services as part of the scope of agreement. A new provision has been added with regard to ICT goods that use cryptography,Footnote 172 which complements the source code provisions and is similar to Annex 8-B, section A.3 of the CPTPP chapter on technical barriers to trade, which addresses practices by several countries, in particular China, that impose bans on encrypted products or set specific technical regulations that restrict the sale of such products.Footnote 173

E Conclusion

The era of big data has ushered in new challenges for global trade law. Policymakers are faced with the extremely difficult task to match the existing, largely analogue-based, institutions and rules of international economic law with the dynamic, scruffy innovation of digital platformsFootnote 174 and data that flows regardless of state borders. At the same time, and this only makes the task more taxing, it is evident that the regulatory framework that will be chosen will have immense effects on innovation and the fate of the data-driven economy,Footnote 175 as well as on fundamental rights beyond the province of the economy, such as the protection of citizens’ privacy. Despite the importance and the urgency of finding appropriate governance solutions, global trade law has not undergone a radical overhaul so far and legal adaptation has been slow and patchy, as this chapter showed. PTAs have become the preferred venue, where digital trade rules have been adopted – on the one hand, so as to compensate for the lack of progress under the umbrella of the WTO and on the other hand, and more importantly, so as to create new rules that address new trade barriers, such as data localization measures; new and pressing concerns, such as the acute need to interface trade and personal data protection mechanisms, and overall, to provide a regulatory environment that is conducive to the practical reality of digital trade and that provides a level of legal certainty for all actors involved. It has been the chapter’s objective to provide a better understanding of this newly emerged governance landscape by tracing broader developments and trends, by looking in particular at the data-related rules across PTAs and analyzing more closely the most sophisticated templates of e-commerce chapters so far, as found in the CPTPP and the USMCA.

The understanding of the existing rules on digital trade and their evolution over time is absolutely essential for future attempts of individual states and of the international community to grapple with the digital challenge. It may be important also for other governance actors, such as companies, think tanks, non-governmental organizations and even individual citizens who wish to more actively engage in the rule-making processes in trade agreements, which by definition tend to be behind closed doors and with little to none stakeholder involvement.Footnote 176 The experience gathered in PTAs may also be invaluable for the ongoing reinvigorated efforts in the WTO to reach an agreement on electronic commerce, as well as in new bolder deals that go beyond existing commitments and look at a range of emerging issues, such as digital identity, AI, electronic invoicing and open data, such as those covered under the DEPA.

As a final thought, one may stress that the data economy has placed higher demands on regulatory cooperation.Footnote 177 As the complexity of the data-driven society rises, enhanced regulatory cooperation seems indispensable for moving forward, since data issues cannot be covered by the mere ‘lower tariffs, more commitments’ stance in trade negotiations but entail the need for reconciling different interests and the need for oversight. In this context, while the paths for engaging in and advancing regulatory cooperation would ideally be followed in the multilateral forum,Footnote 178 preferential trade venues can serve as governance laboratories. The way forward may be truly bright but remains highly (and perhaps unfortunately so) dependent on the role that the key players, the United States, the EU and China, are willing to assume.

A Introduction

Innovation in information and communication technology (ICT) has been one of the key drivers of economic globalization. As a result, the volume of goods and services and, therefore, cross-border data flows have been increasing at an exceptional speed. The World Trade Organization (WTO) and its members have early on realized the importance of establishing global rules for guiding these processes. Already at its Second Ministerial Conference in 1998, the WTO adopted the Declaration on Global Electronic Commerce and called for the establishment of a work programme on e-commerce. The work programme has been implemented by four of the WTO’s bodies which have regularly reported on the developments,Footnote 1 and the General Council has periodically reviewed the progress of the programme. Based on the minutes of the meetings of the General Council, Figure 2.1 maps the number of interventions by WTO members related to the topic of e-commerce. The data shows important variation in terms of attention given to the topic over time. After a substantial interest on e-commerce–related issues in the late 1990s and the early 2000s, the preoccupation with the topic dropped dramatically from 2003 until around 2011. Overall attention has only picked up again in the past few years. In preparation for the Eleventh Ministerial Conference (MC11) in Buenos Aires in December 2017, e-commerce was back on the table and the subject of many of the interventions made in the General Council.

Figure 2.1. Interventions on e-commerce in the WTO General Council, 1995–2018

Following intensified discussions, seventy-six WTO members issued a joint statement on e-commerce during the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos in January 2019 in which they ‘confirm [their] intention to commence WTO negotiations on trade-related aspects of electronic commerce’, ‘seek to achieve a high standard outcome that builds on existing WTO agreements and frameworks with the participation of as many WTO Members as possible’ and ‘continue to encourage all WTO Members to participate in order to further enhance the benefits of electronic commerce for businesses, consumers and the global economy’.Footnote 2

Notwithstanding the newly found interest in e-commerce topics at the multilateral level, we observe that the WTO has been rather passive in its approach to address the data-related changes in the world economy. If regulatory solutions have been promoted, it was mostly driven by unilateral or extraterritorial approaches by the main trading powers. Given the absence of progress in rule-making in the WTO for some time now and a growing set of unilateral policies, the negotiators of preferential trade agreements (PTAs) have themselves attempted to shape the rule book for the twenty-first-century world economy – rules that would address needs resulting from an ever more integrated and data-driven economy. The first PTA that had an electronic-commerce provision was the Jordan–US PTA in 2000 and the first data flow provisions go back to the Korea–US PTA concluded in 2007. So, these types of provisions are a rather recent phenomenon in trade agreements, but it clearly shows that WTO members have shifted the venue for rule-making from the WTO to the world of PTAs starting in the early 2000s.Footnote 3

This chapter focuses on data-related provisions in PTAs and explores trends and patterns over time. We attempt to map clusters and models that have emerged. Related to this, we also focus on who the ‘rule-makers’ are in this regulatory area. If PTAs are best understood as ‘laboratories’ for global rule-making, we investigate in this chapter which governments are pivotal in pushing regulatory ideas and templates.

The chapter is organized as follows: first, we provide a short discussion of the literature that provides the backbone and rationale for the data collection. We then present particular indicators aggregated from the data that attempt to capture various salient dimensions of data flow–related provisions in PTAs. This is followed by an enquiry into the trends over time using these indicators, exploring the rule-makers’ roles through both text-as-data analyses and manual coding of data-related design features. Finally, we graphically explore bivariate relationships that speak to potential explanations why we would expect to see variation in PTA design in this domain. The chapter concludes by outlining possible next research avenues in the area of digital trade governance.

B A Look at State of the Art

Various strands of literature in international relations and political economy provide the backbone for collecting and analyzing PTA design features – some of them address general debates regarding the move towards more law, the relationship between multilateralism and regionalism or on rule-making versus rule-taking, the role of diffusion and debates specific to data flows and regulatory responses. We have mapped some of these debates in this chapter.

The call for more fine-grained information on the content of international agreements has been around for quite a while. Both the legalization as well as the rational design literatures provide useful guidance for choosing the types of design features to focus on.Footnote 4 Both literatures develop indicators and propose measures to account for treaties’ scope, degree of obligation as well as flexibility features. In particular in the trade literature on PTAs, various indicators have been further developed – such as with regard to the depth of an agreement which captures the degree to which measures may lead to increased market integrationFootnote 5 or with regard to various types of flexibility tools which allow for legally imposing barriers, normally for a limited period of time.Footnote 6 These conceptualizations are also insightful when mapping data flow provisions as part of PTAs.

Another strand of literature to which this chapter speaks is the work on regime complexity, which is usually defined as a set of non-hierarchical overlapping institutions.Footnote 7 The universe of PTAs with over one thousand agreements, where all WTO members are participating actors, serves as an interesting laboratory of how regime complexity affects the behaviour of states both in collaborative and conflictive fashions. Linked to the concept of regime complexity is the emerging attention given to diffusion drivers and effects,Footnote 8 which asks the essential questions of why states sign PTAs; what the role of competition with other trading nations is; how learning and mimicking from neighbouring countries impact the decision to engage in PTAs, or whether PTA signature and the treaty commitments are a result of coercion by powerful states that aim to have their templates and models reflected in as many treaties as possible. Both, the regime complexity theories and diffusion theories, provide strong testimony to how international treaties are interdependent and serve as a cautionary note of analyzing single agreements in isolation of other treaties. Within the study of international institutions and international trade, additional debates have emerged, focusing on the groups of countries that promote their own rules (‘rule-makers’) and the ones that are on the receiving end of global regulation (‘rule-takers’). This chapter focuses on the conditions under which rules diffuse using a mix of methods, including textual analyses.Footnote 9

Finally, research on trade and data flows can build on the work that has zoomed in on the relationship between the promotion of liberalization and a government’s objective to protect public interests. While the early trade literature focused on various linkages, such as trade and human rights and trade and environment,Footnote 10 more recently the concept of optimal protection of individual rights related to data protection has become more central. Following the old idea of ‘embedded liberalism’,Footnote 11 we are interested in how liberalization in data flows related to trade and services goes hand in hand with governments’ demands for flexibility or escape instruments to protect citizens’ interests in terms of privacy, and therefore pursuing social goals.

C Design Dimensions and Related Concepts

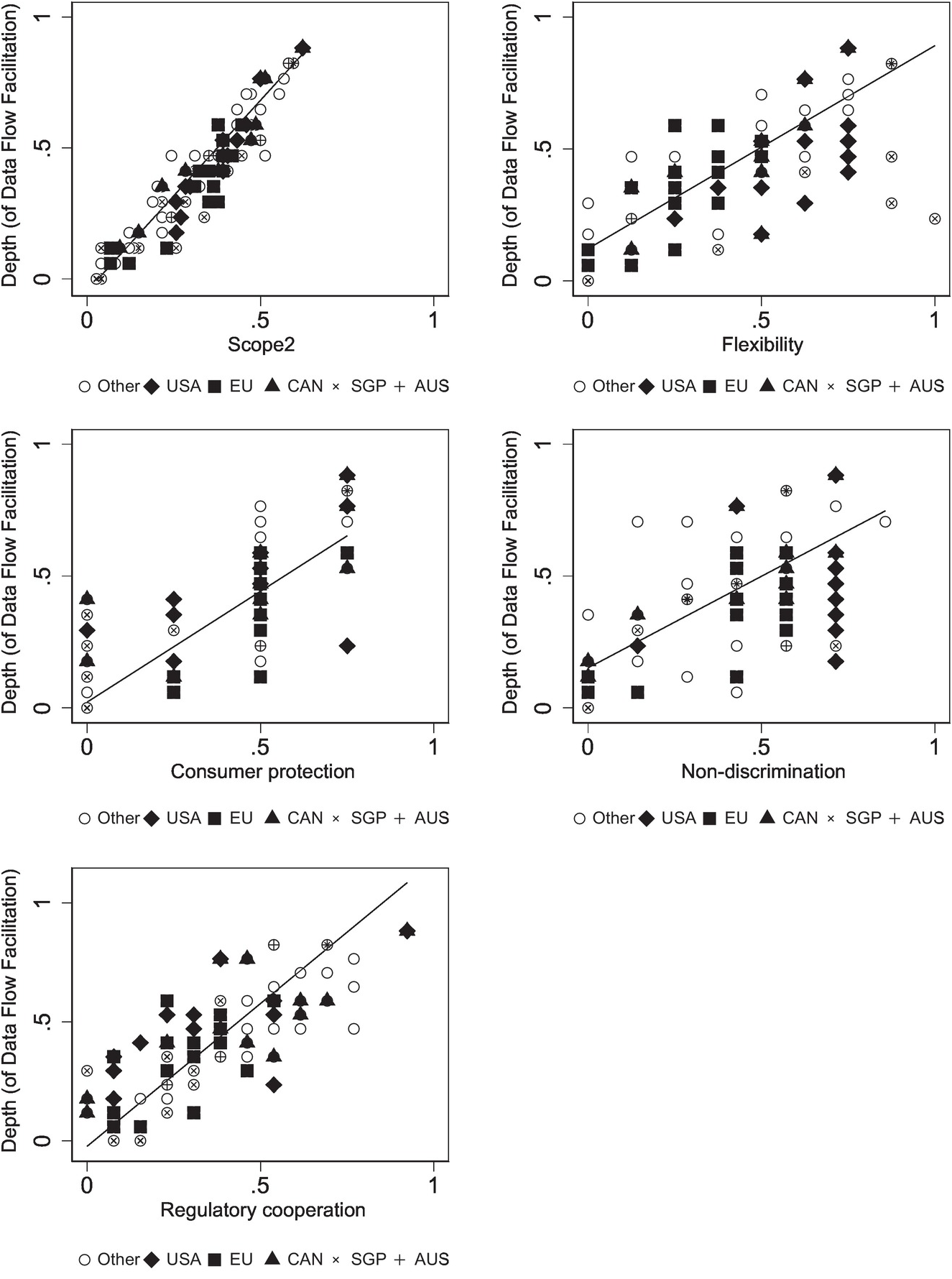

In recent years, research on trade agreements has made substantial progress by unpacking the various design features in PTAs to explore variation across treaties.Footnote 12 We follow this work by zooming in on data-relevant provisions. The data presented below is based on seventy-four single variables focusing, on the one hand, on the electronic commerce chapters and, on the other hand, on data-relevant provisions in other PTA chapters, including services, intellectual property rights and specific rules on ICT, data localization and similar content. The data is then aggregated to produce a number of indicators measuring various key dimensions derived from the earlier literature discussion. In the following, we briefly describe the different concepts and the types of variables that we draw upon to construct these.

I Scope

This concept measures the attention paid to data-related provisions. Scope is different from depth, as it does not capture the degree of obligation and commitment, but rather provides information about the extent to which the topic is covered within the agreement.Footnote 13 Therefore, we construct two different measures for scope or coverage: Scope 1 is the word count for the electronic commerce chapter; scope 2 is the number of total provisions found in the electronic commerce chapter. Scope 1 has a maximum of 3,206 words and the average value is 793. Scope 2 is an additive index which ranges from 0 to 74.

II Depth of Data Flow Facilitation

This measure comes closest to what is in the literature described as the depth of the agreement.Footnote 14 In this case, depth is thought of in relation to commitments, which tend to make trading easier when data transfer is involved. Here we create an additive index of seventeen variables that include rules for facilitating trade and providing for a regulatory environment to foster trade in data – these range from free movement of data commitments, promoting paperless trading and electronic signatures, and advocating self-regulation of the private sector to abstain from data localization measures. This additive indicator ranges from 0 to 17.

III Flexibility

As the literature on international institutions suggests that deeper commitments are also more flexible,Footnote 15 we constructed one indicator that focuses on eight escape and flexibility measures that we detected in the agreements’ texts. These include both general and specific exceptions to commitments as well as reservations. The flexibility indicator ranges from 0 to 8.

IV Consumer Protection

An important and more specific flexibility instrument consists of explicitly foreseeing ways to protect consumer interests. This indicator ranges from 0 to 4 and includes elements of individual rights in relation to data protection, Internet Governance principles, data localization measures or addressing spam.

V Non-discrimination

This indicator measures how much attention treaty drafters have directed to general principles related to non-discrimination, such as treating domestic and foreign actors equally as well as following the most favoured nation (MFN) clause. On top, we add references to the WTO commitments and the need for technology neutrality. The higher the indicator, the more negotiators embed trade agreements within the multilateral trading system aiming for more consistency across treaties.Footnote 16 The indicator ranges from 0 to 7.

VI Regulatory Cooperation

The final indicator measures the degree to which treaty drafters advocate various forms of regulatory cooperation. We compile commitments that call for cooperation on transparency, international alignment in regulatory fora or working together on cybersecurity issues. In addition, we explore whether the treaty mentions working groups or committees to implement the electronic commerce commitments. This indicator is a proxy for how much regulatory cooperation is foreseen in the treaty text. The indicator ranges from 0 to 13.

D Describing Trends and Patterns in Digital Trade Governance

In this section we discuss briefly the evolution of PTAs over time. We provide some descriptive statistics based on the indicators developed earlier, derive a better idea about who the rule-makers are and explore a number of bivariate relations which are suggestive about potential interdependence between design features, but also between treaty content and domestic practice.

The first agreement referring to electronic commerce was signed in 2000. Therefore, we deal with a rather novel issue area for trade regulation. There are no observations prior to 2000 while discussions within the WTO had been going on for a while. This is suggestive to the possibility that governments have prioritized the multilateral arena while then slowly turning to PTAs either because of lack of progress in the WTO (see Figure 2.1), or because of learning effects and development of various government strategies and potentially implicit models. Figure 2.2 shows the steady increase of e-commerce provisions, e-commerce chapters and provisions on free data flow both in absolute numbers and relative to the number of PTAs signed per year.

In total, we have identified ninety-nine PTAs that have at least one data-related provision. Table 2.1 provides the summary statistics for the different indicators outlined earlier and confirms the notion of considerable heterogeneity among PTAs.

Table 2.1. Summary statistics on the indicators

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope 1 | 99 | 793.2 | 669.2 | 17 | 3,209 |

| Scope 2 | 99 | 22.9 | 10.5 | 2 | 46 |

| Depth | 99 | 6.5 | 3.5 | 0 | 15 |

| Flexibility | 99 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 0 | 8 |

| Consumer protection | 99 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0 | 3 |

| Non-discrimination | 99 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 0 | 6 |

| Regulatory cooperation | 99 | 4.3 | 2.7 | 0 | 12 |

In the following figures, we zoom into a selection of indicators and illustrate their evolution over time. Figure 2.3 shows the Scope1 indicator, which captures the number of words related to the regulation of e-commerce and data flows. The median and range of the count of words varies considerably over time. We also observe a number of outliers, including Jordan–Singapore 2004, the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) in 2006 and Australia–Japan 2015. The latter one is an outlier for that year but is following an upward trend. We also observe large variation in the years 2016–2018.

Figure 2.3. The Scope 1 indicator, 2000–2018.

In Figure 2.4 we show the second scope indicator, based on the number of provisions related to the regulation of e-commerce and data flows. Again, we observe that scope increases; however, this does not occur gradually. In most years, we notice a considerable range of provisions as well as a number of outliers. Compared to other PTAs signed in 2006, CEFTA has only few provisions related to the regulations of e-commerce and data flows. In 2007, the same is true for the PTA between Japan and Thailand. In contrast, the Panama–US PTA in 2007 includes a rather large number of provisions on this topic. The PTA between Colombia and Costa Rica presents the top outlier in 2013, the PTA between Central America and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) the bottom outlier. Malaysia–Turkey and Canada–Ukraine present the two outliers in 2014 and 2016, respectively.

Figure 2.4. The Scope 2 indicator, 2000–2018.

Over time, we also detect an increase in the depth (Data Flow Facilitation) indicator (Figure 2.5). Following the above trend, the 2006 CEFTA agreement and the 2007 Japan–Thailand PTA indicate substantially shallower commitments than other agreements in these respective years. The outlier PTAs having substantially deeper commitments in 2013 than other agreements signed in that year are Colombia–Costa Rica as well as Colombia–Panama, most likely inspired by their commitments in one of their recent trade agreements with a rule-maker. In 2015, we observe in Mongolia’s first ever PTA with Japan also deeper commitments in terms of data flow facilitation.

Figure 2.5. The depth indicator, 2000–2018.

Turning to our flexibility indicator (Figure 2.6), we observe that already between 2004 and 2008 PTAs included higher levels of flexibility. Again, CEFTA presents the outlier in 2006, which is not surprising as it also scored low on scope and depth. The bottom outlier in 2015 is the PTA between Canada and Ukraine, which might be explained by the low trade flows in goods and services with substantial data content between the two countries. The top outlier in the same year is the PTA between Australia and Singapore, which could be a result of two countries with usually deep agreements.

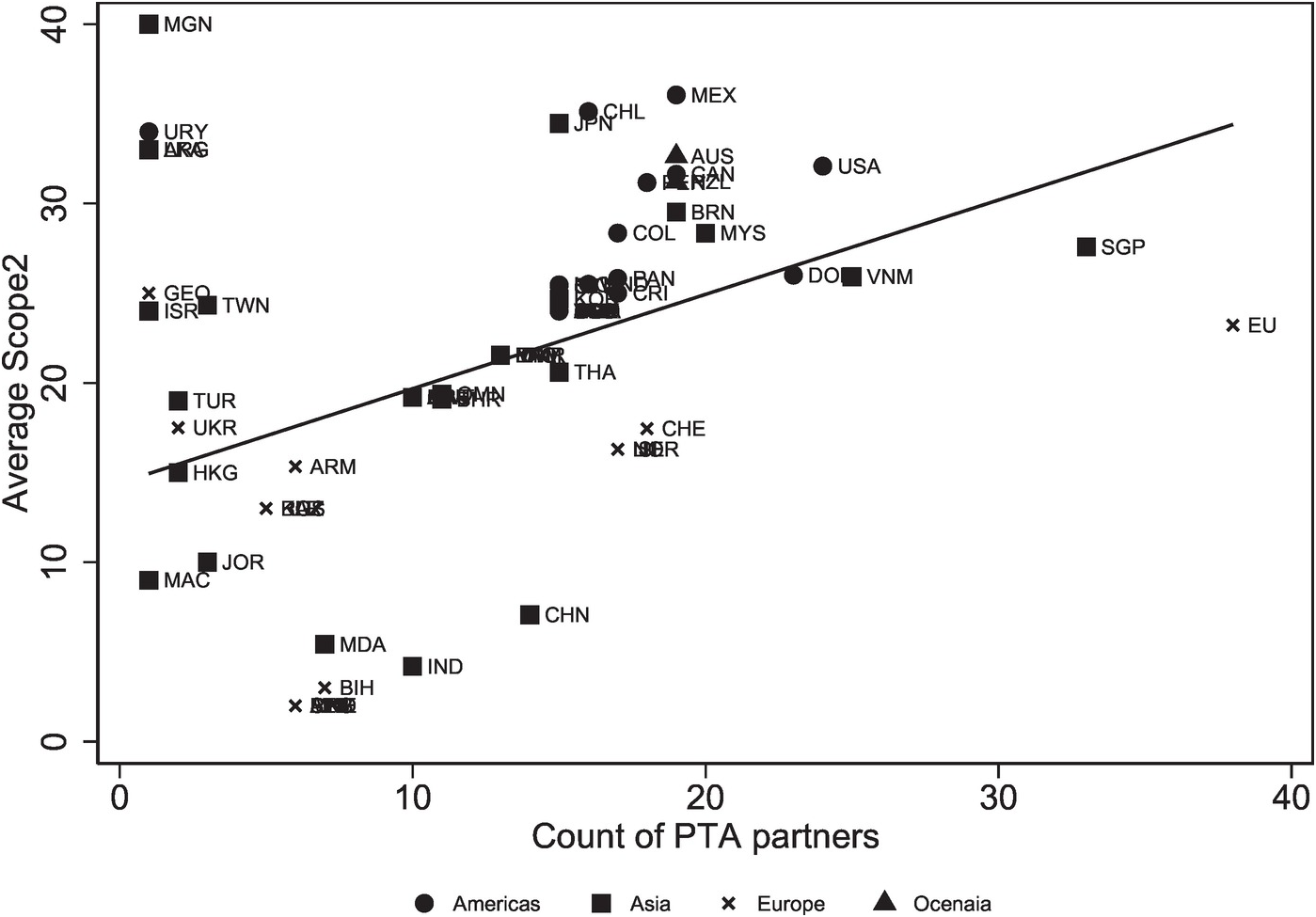

E Of Rule-Makers and Central Actors

The previous sections discussed the various indicators and illustrated their variation over time. In this section, we take a closer look at the signatory countries. In total, eighty-two countries (counting the EU as one actor) are involved in the ninety-nine PTAs which have data flow–related provisions since 2000. As illustrated in Figure 2.7, there is considerable heterogeneity in terms of the number of PTA partners by signatory and the degree of scope measured by the number of provisions. Since 2000, the EU has signed eighteen PTAs with thirty-eight partner countries and, on average, included twenty-three provisions on e-commerce and data flows. Mongolia (MGN) has only signed one PTA (with Japan). In this PTA, however, there are forty provisions on e-commerce and data flows. The United States has signed fewer agreements than the EU, but on average their scope is substantially higher. We also observe that the average scope of agreements with European countries is significantly lower than treaties with countries of the Americas. Oceania is also above average in terms of scope. Finally, African signatories of PTAs are not yet addressing data flow–related provisions. This is surprising given the potential of e-commerce for developing countries.

To illustrate this network of PTAs, we combine the average Scope 2 indicator and the count of PTA partner countries for each signatory country and represent this in Figure 2.8 using instruments of network analysis. In this network, the size of each country is proportional to its weighted centrality. That is, the size of each country is proportional to the product of the number of PTA partners and the average number of provisions on e-commerce and data flows included in all its PTAs. The width of the links is proportional to the number of e-commerce and data flow provisions in a given PTA. Figure 2.8 highlights that there are some countries that are central to this PTA network and therefore potentially influential in diffusing certain regulatory models on e-commerce and data flows. The European Union, the United States and Singapore stand out, but also other countries, such as Australia, Canada or Mexico, are pictured as central actors.

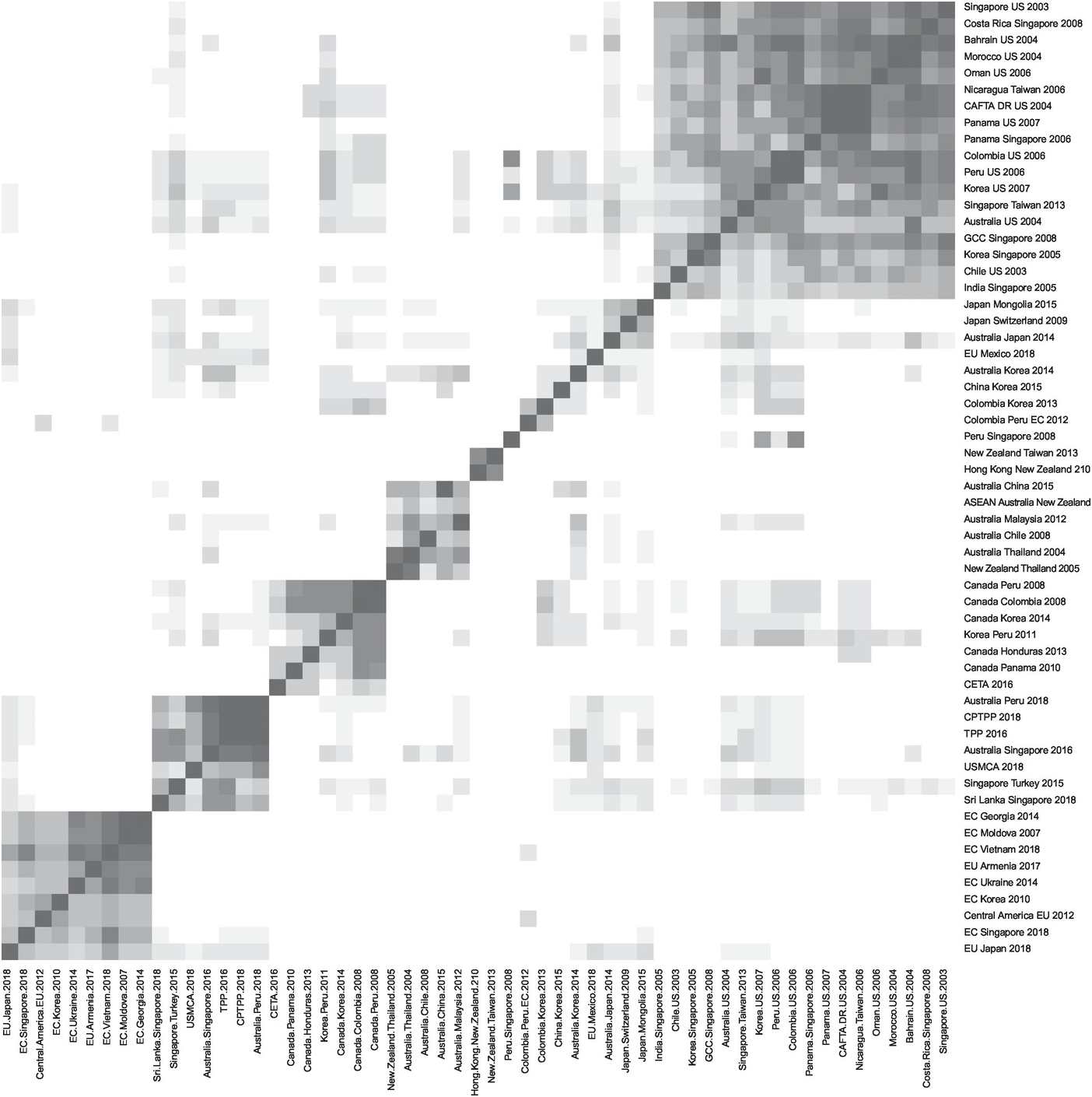

To investigate the patterns that can be graphically observed in the earlier network, we zoom into the subset of PTAs that have not only at least one provision on e-commerce and data flows but a full chapter. Out of the ninety-nine PTAs signed since 2000, seventy-two have a chapter related to e-commerce and data flows. Seven of these PTAs are signed between Latin American countries and only available in Spanish, leaving us with sixty-three PTAs that are available in the English language. Since Singapore and Australia renewed their 2003 PTA in 2016, we only include the latter PTA in this analysis – leaving us with a subset of sixty-two PTAs.

Relying on text-as-data analysis, we compare these sixty-two PTA chapters in the English language to detect potential patterns, more precisely, by employing the plagiarism software WCopyfind to measure the textual overlap between the PTA chapters. The programme allows for a number of refinements. We follow the convention to use a minimum of six consecutive identical words for a match.Footnote 17 All punctuation, outer punctuation, numbers, letter case and non-words are ignored. It should be pointed out that WCopyfind only reports the PTAs that have a minimum of matches between PTAs. In our case, the PTAs between Jordan and Singapore (2004), Canada and Jordan (2009), the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and Vietnam (2015) and between Canada, and the Ukraine (2016) appear to have too little overlap with the other PTAs and were consequently dropped by the programme.