Although war and political conflict have grave consequences, increased national identification and community solidarity during wartime appear to protect mental health. Moreover epidemiological studies in Northern Ireland have indicated comparatively good mental health of the population during the 35-year period of political violence that has affected the region (Reference Cairns, Mallett and LewisCairns et al, 2003), colloquially known as the ‘troubles’. Given the chronic nature of the conflict, the scale of casualties in terms of total population (3500 fatalities from a population of 1.68 million between 1969 and 1998), the effects of the ‘troubles’ have been widely felt (Reference Hayes and McAllisterHayes & McAllister, 2001), and like other conflicts, the impact has not been distributed evenly across the population (Reference CairnsCairns, 1996). Worldwide, those most likely to be affected by conflict are the poorest (World Health Organization, 2002) and within affected countries, those reporting the most experience of violence tend also to be the most socially disadvantaged (Reference Bryce, Walker and GhorayebBryce et al, 1989; Reference Muldoon and TrewMuldoon & Trew, 2000).

The most common psychological consequence of war and conflict is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). To date only a limited number of epidemiological studies have examined the prevalence of PTSD post-conflict (Reference De Girolamo, McFarlane, Marsella, Friedman and GerrityDe Girolamo & McFarlane, 1996). However, these prevalences are often higher than those in countries where conflict is ongoing (Reference DeJong, Komproe and Van OmmerenDe Jong et al, 2003). The course of PTSD may well be linked to community and group identity, as is the stress process (Reference Haslam and ReicherHaslam & Reicher, 2006). In particular, the very high variability in levels of post-traumatic stress in referred and clinical samples in Northern Ireland might in part be attributable to social identity. For instance, Wilson et al (Reference Wilson, Poole and Trew1997) found an incidence of 5% of probable PTSD in police officers exposed to life-threatening incidents during the ‘troubles’ whereas Daly & Johnston (Reference Daly and Johnston2002) reported 67% among those held at gunpoint in a bar towards the end of the ‘troubles’. This comparatively low rate among police officers indicates the value of a consolidated identity to preserving mental health. The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), the police force in Northern Ireland during the ‘troubles’, was strongly identified with one community and officers were highly committed to its identity (Reference MulcahyMulcahy, 2006). However, those exposed in the bar incident were bystanders and the 1994 ceasefire had led many to believe the conflict was over.

The ability to cope with stress is intrinsically related to psychological and material resources (Reference Lazarus and FolkmanLazarus & Folkman, 1984), which are likely to be adversely affected by repeat traumatisation experienced during politically motivated conflict. Experience and appraisal of trauma tends to be related to both poverty (Reference MuldoonMuldoon, 2003) and social identity (Reference Haslam, Jetten and O'BrienHaslam et al, 2004).

The aims of this study were first to examine the population prevalence of PTSD in Northern Ireland post-conflict and to examine the relationship between PTSD and the strength of national identification. Second, although a comparatively affluent society, deprivation within the region remains a significant social issue and therefore we examined PTSD across socio-economic groups. Finally, lifetime experience of violence was assessed to determine the relationship between chronic traumatisation and PTSD.

METHOD

Sample

A random sample of household telephone numbers was drawn from domestic listings for Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. These numbers were matched with the relevant postal address and a letter was sent to selected households, explaining the nature and purpose of the study. Each household was then contacted by telephone. Where more than one adult resided in a household, the last birthday technique was used to randomise the selection of respondents included in the sample.

The survey was carried out using computer-assisted telephone interviewing, which facilitates interview monitoring via listening in facilities. A quota control mechanism controlled the number of respondents by location based on adult population statistics from the latest census (2001 Northern Ireland, 2002 Republic of Ireland). The final sample included 3000 participants, 2000 in Northern Ireland and 1000 in the border counties of the Republic. Overall 49% of those contacted refused to participate, with a 48% refusal rate in Northern Ireland and 52% in the Republic. Demographic factors profiled included age, gender, religious affiliation, residential jurisdiction, highest educational qualification and annual household income. The final sample was comparable to the census profile of the population (Table 1). The average length of interview in the survey was approximately 18 min. Fieldwork for the survey commenced on 5 October 2004 and was completed on 31 December 2004.

Table 1 Sample profile according to gender, age and jurisdiction

| Northern Ireland | Republic of Ireland | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 848 | 42 | 459 | 46 | 1307 | 44 |

| Female | 1152 | 58 | 541 | 54 | 1693 | 56 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18-24 years | 130 | 7 | 67 | 7 | 197 | 7 |

| 25-44 years | 744 | 37 | 309 | 31 | 1053 | 35 |

| 45-64 years | 737 | 37 | 456 | 46 | 1193 | 40 |

| 65+ years | 389 | 20 | 168 | 17 | 557 | 19 |

| Total | 2000 | 100 | 1000 | 100 | 3000 | 100 |

Measures

PTSD Checklist

The specific stress version of the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, a 17-item self-report instrument, was employed based entirely on DSM–IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The instrument has been used for screening in telephone surveys (Reference Schuster, Stein and JaycoxSchuster et al, 2001; Reference Schlenger, Caddell and EbertSchlenger et al, 2002) and is well regarded (Reference Solomon, Keane, Newman and CarlsonSolomon et al, 1996), with impressive reliability and validity (Reference Blanchard, Jones-Alexander and BuckleyBlanchard et al, 1996; Reference Walker, Newman and DobieWalker et al, 2002). Importantly, a highly sensitive and specific cut-off score of 30 can be used to identify people with the disorder (Reference Blanchard, Jones-Alexander and BuckleyBlanchard et al, 1996). In the first instance respondents were asked whether they had encountered a distressing event as a result of the ‘troubles’. Those who reported a particularly distressing event then completed the 17-item PTSD Checklist.

Identification with national group

Subsequent to stating their preferred national identity, respondents were asked to rate the importance of their national identity using four items from Luhtanen & Crocker's (Reference Luhtanen and Crocker1992) collective self-esteem scale. Higher scores indicate stronger national identity.

Experience of political violence

The development of the questions to assess experience of violence was guided by previous research (Reference MacksoudMacksoud, 1992). Questions were worded to maximise similarity between this and previous studies in Northern Ireland (e.g. Reference Cairns, Mallett and LewisCairns et al, 2003). Two further questions regarding respondents’ experience of the ‘troubles’ were included: one asked whether respondents viewed themselves as a victim of the ‘troubles’ (Reference Cairns, Mallett and LewisCairns et al, 2003); a final question asked whether they had used alcohol, prescription or other drugs to cope with their experiences (Reference Bleich, Gelkopf and SolomonBleich et al, 2003).

Ethical considerations

Participants were given details of the research in writing when invited to participate. The confidentiality and anonymity of all responses was assured; participants were also given the opportunity to refuse to participate and/or to withdraw at any time. A free-phone number where trained counsellors were available to discuss issues arising from the interview was provided at the end of all interviews. This service was active for 6 months from the start of the project. No calls were received at this number and no participant requested counselling via this system.

RESULTS

Of the 3000 respondents, 1269 (42%) reported experience of a distressing event as a result of the ‘troubles’ and thus were assessed for PTSD with the PTSD Checklist. Based on standard cut-off scores (Reference Walker, Newman and DobieWalker et al, 2002) 10% of respondents (n=299) had symptoms severe enough to warrant a diagnosis of PTSD. Of these 299 people, 239 were from Northern Ireland (12% prevalence) and 60 from the border counties of the Irish Republic (6% prevalence). This difference was significant (χ2=13.92, d.f.=1, P<0.01). No gender or religious differences were observed.

Characteristics of those with PTSD

Those classified as having PTSD were less likely to have third-level education (20 v. 31%; χ2 = 19.4, d.f.=7, P<0.01) and were more likely to be unemployed owing to job loss (4.3 v. 1.6%) or unable to work owing to illness (6.7 v. 1.3%; χ2 = 29.4, d.f. = 8, P < 0.01). People with PTSD were more likely to be in unskilled, partly skilled or manual occupations (10.6 v. 6.1%, 16.6 v. 13.5%, 13.8 v. 11.1% respectively; χ2 = 14.2, d.f. = 5, P < 0.01) (6.1%, 13.5% and 11.1% respectively). People with PTSD also reported lower average household incomes. In Northern Ireland, 33% of respondents with probable PTSD had a household income of less than £20 000 and 14% had an income of less than £10 000 per annum. In comparison, 24% of households overall reported an income of less than £20 000, with only 6% with an income less than £10 000. In the Republic, 32% of people with PTSD lived in a household with an income of less than €20 000 v. 16% for those without PTSD.

Table 2 Substance use to help with experiences related to the ‘troubles’ among those classified with and without probable PTSD according to the PTSD Checklist

| Substance | Probable PTSD (n=60) | Without PTSD (n=1029) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Alcohol | 38 | (12.7) | 22 | (2.3) |

| Prescribed drugs | 47 | (15.7) | 15 | (1.5) |

| Other drugs | 13 | (4.3) | 8 | (0.8) |

People with PTSD more frequently reported using alcohol to cope with their experience of the ‘troubles’ (12.7 v. 2.3%; χ2 = 48.785, d.f. = 1, P < 0.01). Similarly, 15.7% reported using prescribed medication to cope with the ‘troubles’ compared with 1.5% of the other respondents (χ2 = 95.801, d.f. = 1, P < 0.01). Finally six times as many people with PTSD reported use of other drugs to cope with the ‘troubles’ (4.3 v. 0.8%; χ2 = 11.361, d.f. = 1, P < 0.01).

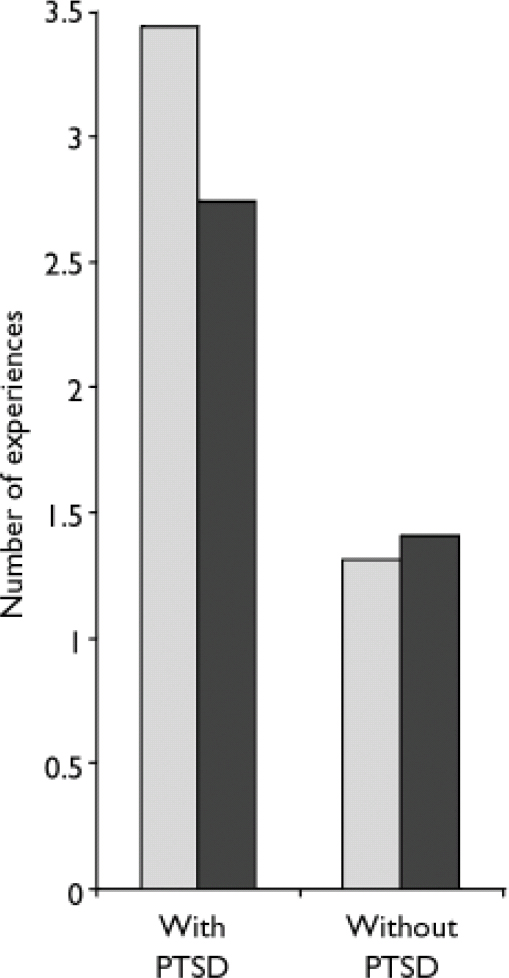

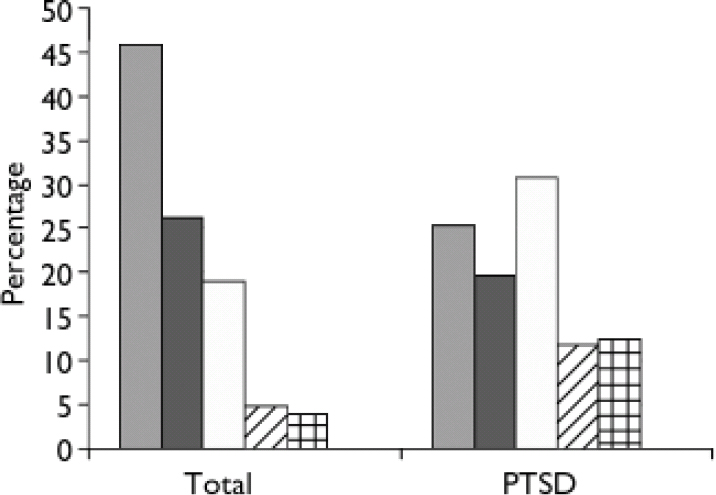

People with PTSD reported more direct (F(1, 1267)=149, P < 0.001) and indirect experiences (F(1, 1267)=85, P < 0.001) of the ‘troubles’ (Fig. 1). The importance attached to national identity was also related to PTSD. People with PTSD rated their national identity as less important (F(1, 1138) = 6.78, P < 0.01). Perceived victimhood was also related to PTSD symptoms (χ2=171, d.f. = 4, P < 0.001). Only 9% of respondents often or very often considered themselves victims of the ‘troubles’; however, 24% of those with PTSD stated that they often or very often considered themselves to be a victim of the ‘troubles’. On the other hand and perhaps more surprisingly, 46% of those with symptoms severe enough to suggest clinically significant PTSD never or rarely considered themselves victims of the ‘troubles’ (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 Mean number of direct and indirect experiences of the ‘troubles’ according to classification with the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist. PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; ░, direct experiences; ▪, indirect experiences.

Fig. 2 Percentage of total sample and subsample with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who consider themselves to be ‘victims’ of the ‘troubles’. ░, Never; ▪, rarely; □, sometimes; ![]() , often;

, often; ![]() , very often (the percentage answering ‘Don't know’ is too small to show).

, very often (the percentage answering ‘Don't know’ is too small to show).

DISCUSSION

Main findings

The prevalence of probable PTSD in Northern Ireland after a period of protracted political conflict is approximately 10%. This is higher than that observed in police officers exposed to life-threatening incidents during the same ‘troubles’, who have been reported to have a strong sense of shared identity (Reference MulcahyMulcahy, 2006). Similarly, the weaker national identities of people with probable PTSD suggests that social identity can protect mental health in situations of violence, in accordance with the integrated social identity model of stress (Reference Haslam and ReicherHaslam & Reicher, 2006). In conflict situations, identities underpin the conflict (Reference KelmanKelman, 1999) and consequently deliberate attempts to reduce the salience of these identities post-conflict (Reference Macginty, Muldoon and FergusonMacGinty et al, 2007) might inadvertently affect mental health. Clearly, longitudinal studies are needed to explore any such effects more fully.

The observed prevalence of PTSD is similar to that in other regions affected by long-term conflict, such as Israel and Sri Lanka, and higher than that observed subsequent to acute incidents such as the 9/11 attacks in the USA (Reference DeJong, Komproe and Van OmmerenDe Jong et al, 2003). Although there are clear differences between both the situations and the studies, overall the incidence of PTSD would appear to be higher in situations of ongoing or chronic political violence rather than subsequent to acute incidents. Similarly, we found that those with PTSD were more likely to report multiple direct and indirect experiences, with direct experience appearing to have a more powerful impact. This provides further evidence that previous exposure needs to be considered when evaluating the relative impact of traumatic events in situations of war and violence, not least because of the resource-depleting effects of multiple traumatisation.

However, half of our respondents reported that they had encountered no particularly distressing incident during the ‘troubles’. The impact of conflict is therefore not distributed evenly — some have suffered not at all and others have suffered greatly. Respondents of lower socio-economic status were disproportionately affected by PTSD. Although symptoms might contribute to disadvantage (as a result of disability and unemployment), the fact that many had low educational status suggests that social disadvantage increases the risk of developing PTSD. Of course, social disadvantage might also increase the risk of engaging with the conflict (Reference CairnsCairns, 1996), thereby increasing the risk of exposure to trauma. In reality, the coincidence of deprivation and multiple traumatisations in situations of political violence are likely to be twin, inextricably linked risks. That said, those identified as having probable PTSD represent a particularly vulnerable and disadvantaged group in terms of financial, psychological and social capital.

Methodological limitations

Although our sample was comparable to the general population in Northern Ireland, no details are available regarding the mental health status of non-respondents. Reluctance to participate is reflective of the ‘whatever you say, say nothing’ approach to engaging in any contentious discourse which is evident in many societies with conflict (Reference CairnsCairns, 1996). Indeed a similar Israeli study achieved a 57% response rate (Reference Bleich, Gelkopf and SolomonBleich et al, 2003). The limited verification of respondents’ accounts of distressing events is also important to the interpretation of the findings. Although the greater prevalence of direct and indirect experience in people with probable PTSD provides a form of verification through triangulation, it is possible that respondents did not actually experience life-threatening events personally. Although these limitations may act to alter overall patterns, a 10% prevalence rate is consistent with findings from Israel (Reference Bleich, Gelkopf and SolomonBleich et al, 2003) and estimates following explosions (25%; Reference Hayes and McAllisterHayes & McAllister, 2001) and being a victim of violence in Northern Ireland (14%).

Clinical implications

Many of those with symptoms suggestive of PTSD do not consider themselves victims of the ‘troubles’ and hence it is not surprising that some have resorted to self-medication instead of seeking professional help: our evidence shows a higher reported misuse of substances. Current government policy is targeting services towards ‘victims of the troubles’. Our findings suggest that advertising or targeting resources towards ‘victims’ might act as a barrier to those who have been most adversely affected. Finally, holistic approaches that consider previous traumatic experiences and socioeconomic background are crucial to understanding the impact of any specific incident in conflict situations.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by an award to O.T.M. from the Cross-Border Consortium under the EU Peace II Programme and was financed in part by the UK and Irish governments.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.