1. Introduction

This paper discusses the interplay of semantics, syntax, and pragmatics of (complex) noun phrases in German dialects in Austria from a variationist perspective. We focus on language variation and change in the use of adnominal syntactic constructions of expressing semantic relations of possession. We examine the synchronic variation of these constructions by means of the first comprehensive apparent-time study of Austria’s traditional dialects.

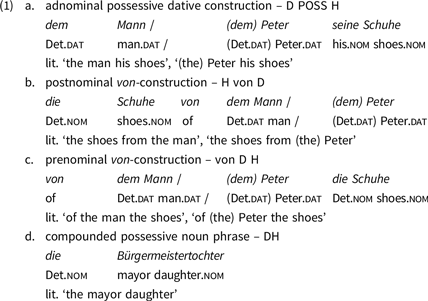

Speakers of German dialects have different syntactic variants at their disposal to express semantic relations of possession. The most widespread adnominal constructions considered to be used in nearly all traditional German dialects—including the German dialects in Austria—are summarised in (1).Footnote 1 These constructions, which we describe in more detail in Section 2, usually consist of two components: a possessor phrase that syntactically is the dependence (= D) and a possessum phrase, which is the head (= H) of the entire construction (Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b; Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm and Frans2003). Furthermore, many of these constructions have so called construction markers, “overt elements which show explicitly that D and H are related in a specific way” (Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm and Frans2003:621). In German dialects, these construction markers can be, for example, possessive elementsFootnote 2 (POSS) such as seine ‘his’ in (1a) or prepositions such as von ‘of’ in (1b, c).

Note that the postnominal (NP NPGEN) and the prenominal genitive constructions (NPGEN NP) in (2a, b), which are attested for earlier stages of German (OHG, MHG) and which are also used frequently in varieties of Standard German, are considered to have almost disappeared from the traditional German dialects and many non-standard varieties (Fleischer & Schallert, Reference Fleischer and Oliver2011:84–87).

Constructions of the type (2b), prenominal genitive constructions with proper names, are assumed to have survived in few dialects only (Fleischer & Schallert, Reference Fleischer and Oliver2011:86). In a handbook article, Koß (Reference Koß, Werner, Ulrich, Wolfgang and Wiegand1983) mentions Low German and Alemannic dialects; however, it does not become clear from his broad overview and the illustrating map (Koß, Reference Koß, Werner, Ulrich, Wolfgang and Wiegand1983:1244) whether he included idiomatically “frozen”, that is, unproductive genitive forms or not. Highest Alemannic dialects in the canton of Valais (Switzerland) are often mentioned as rare examples of a still productive use of genitive constructions (cf., Bart, Reference Bart2020; Bohnenberger, Reference Bohnenberger1913; Henzen, Reference Henzen1932; Kasper, Reference Kasper, Michael, Markus and Jürgen Erich2015a, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b; Wipf, Reference Wipf1910). Thus, it came quite as a surprise that Scheutz (Reference Scheutz2016:64-66) found instances of these constructions in South Bavarian dialects of South Tyrol (Italy). Unfortunately, little is known for the situation in Austria where South Bavarian (e.g., in Carinthia) and Highest Alemannic (in Vorarlberg) dialects also exist. Our assumption was that such genitive forms could be found in Austria as well.Footnote 3 If so, the question arises whether they manifest relicts of earlier and more widespread structures or innovations in Austria’s traditional dialects (e.g., through contact with standard varieties).

The fact that prenominal genitive constructions as in (2b)—if they are ever used in a certain dialect—are only attested with proper names (e.g., Peters Schwester ‘Peter’s sister’) and in some kinship expressions serving as proper names (e.g., Mutters Bruder ‘mother’s brother’) indicates that semantic properties of the NP affect the use of a certain syntactic construction.

Kasper’s studies on the syntax of Hessian dialects underline the complex interplay of semantic, spatial, and syntactic factors. Kasper (Reference Kasper, Michael, Markus and Jürgen Erich2015a, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b, Reference Kasper2017), for example, shows that even in a relatively small region like Hesse, dialects seem to license certain constructions according to semantic factors in different ways. The expression of kinship relations (e.g., die Tochter des Bürgermeisters ‘the daughter of the mayor’) can serve as an example here. In the dialects from the north and west of Hesse, the von construction (postnominal: die Tochter vom Bürgermeister, prenominal: vom Bürgermeister die Tochter) is preferred, whereas in the Central Hessian and Rhine Franconian dialect regions the adnominal possessive dative construction (dem Bürgermeister seine Tochter) is used more frequently (cf., Kasper, Reference Kasper2017:313). Moreover, with respect to the use of the adnominal possessive dative construction in the different dialects of Hesse, the position of the possessor (D) on the “empathy hierarchy” (following the modification of Kasper Reference Kasper2017) seems to play an important role (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Empathy hierarchy (modified from Kasper, Reference Kasper2017)

Whereas partitive (or meronymic) relations with an inanimate but anthropomorphic possessor (e.g., Fuß der Puppe ‘foot of the doll’) can be expressed by an adnominal possessive dative construction (der Puppe ihr Fuß) in the south of Hesse, this is not possible in the other dialects of Hesse where the adnominal possessive dative construction requires at least an animate possessor (Kasper, Reference Kasper2017:319). These dialects clearly prefer prenominal von-constructions, such as in (1c). Thus, the areal distribution of the adnominal possessive dative construction with anthropomorphic possessors in partitive/meronymic relations seems to indicate the spread of a grammaticalization process from the south to the north in this particular region (Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b).

Kasper (Reference Kasper, Michael, Markus and Jürgen Erich2015a, Reference Kasper2017) shows many more of these relationships for the dialects in Hesse. Aside from Kasper’s work on the particular situation in Hesse, there are few studies about the situation in other German dialects (cf., for example, Koß, Reference Koß, Werner, Ulrich, Wolfgang and Wiegand1983 for a broad overview of all German dialect regions; Kallenborn, Reference Kallenborn2019 for Mosel Franconian dialects; Nickel, Reference Nickel and Gabriele2016 for East Franconian dialects in Bavaria; Bart, Reference Bart2020 for Swiss German dialects). Apart from Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenz (Reference Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenzaccepted), who focus on sociolinguistic and stylistic factors of variation between standard varieties and dialects, and a small pilot study by Breuer and Bülow (Reference Breuer, Lars, Lars, Kristina and Ann-Kathrin2019:258–64), with data from Vienna, there are virtually no studies on German in Austria, and there is a complete lack of studies on adnominal possessive constructions in the dialects of Austria.Footnote 4

Thus, in view of the wide range of adnominal syntactic constructions to express semantic relations of possession in varieties of German, this article aims to explore the structure of the geographical variation of such constructions in Austria’s traditional dialects (Research Question 1). We will then try to find semantic and pragmatic factors in order to explain the main patterns of variation. In doing so, we want to re-examine the validity of previous attempts to explain possessive constructions—in particular, with respect to the conceptual domains of possession and the ranking of the possessor on the empathy hierarchy (Research Question 2). While semantic aspects of possessive constructions have so far been at the center of attention of the German research tradition (for an exception, see Demske, Reference Demske2001), we focus also on the role of pragmatics in this paper. Thus, we evaluate and discuss the concepts of accessibility and referential anchoring in the process of encoding possessive relations (Research Question 3).

In order to find answers to these three research questions, spoken/oral as well as written dialect data will be analyzed. The spoken/oral data come from guided interviews of 162 informants from forty rural locations in Austria. Additionally, 103 of these informants (from thirty-seven locations) responded to a written syntax questionnaire. The questionnaire data will be systematically compared to the data from the direct recordings.

In what follows, we will first explain the conceptual domains of possession and the above-mentioned constructions in more detail (Section 2). In Section 3, we will present our data and methods before we report the results in Section 4. Finally, the results will be summarized and discussed (Section 5). Section 6 will offer a brief conclusion.

2. The conceptual domains of possession and syntactic strategies to express them

There is a long and extensive research interest in linguistic forms that express the semantic relations of possession (e.g., Bart, Reference Bart2020; Behaghel, Reference Behaghel1923; Demske, Reference Demske2001; Heine, Reference Heine1997; Henzen, Reference Henzen1932; Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm and Frans2003; Lehmann, Reference Lehmann2002; Weise, Reference Weise1898; Weiß, Reference Weiß, Sjef, Olaf and Marika2008). It is important to note that the focus is not only on semantic relations, which can be defined as “ownership relations” in a narrow sense but also on source domains that encompass possessive relations in a broader sense, including particularly partitive/meronymic relations and kinship relations (cf., Heine, Reference Heine1997; Kasper, Reference Kasper, Michael, Markus and Jürgen Erich2015a, Reference Kasper2017). Thus, it is “notoriously difficult” (Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm and Frans2003:141) to clearly define and delimit the concept of possession from related concepts. Moreover, the concept of possession is “inherently vague or fuzzy” (Heine, Reference Heine1997:1).

In this section, we will first introduce the key domains of possession before we then describe and discuss the linguistic and sociolinguistic restrictions of the most important adnominal constructions of expressing them in Austria’s traditional dialects.

2.1 Possession: conceptual domains and concepts

Possession is a complex cognitive concept that is assumed to be composed of different conceptual domains and resources (cf., Heine, Reference Heine1997; Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b; Seiler, Reference Seiler1983). At the core is the domain “possession as ownership,” as, for example, in the usual reading of (3a). Other important domains are “kinship” relations (3b) and “partitive/meronymic” relations (3c).

A widely discussed aspect of the concept of possession is the alienability/inalienability distinction first established by Lévy-Bruhl (Reference Lévy-Bruhl1914). This distinction refers to the relationship between the possessum and the possessor. Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou, Martine and Yves2003:167), for example, defines that “alienable possession calls for a possessor that does the acquiring, while inalienable possession is inherent, intimate possession that does not need to be acquired.” Thus, alienability means that the possessum can change the possessor (and vice versa). In (3a), for example, Peter’s car can easily change hands. Therefore, the ownership relation between Peter and car needs to be established. This is different in (3b) and (3c) where the kinship and partitive/meronymic relation is inherently given and thus inalienable. There are, however, controversial cases in which it is not easy to define a relation as alienable or inalienable. This seems to be culture and language specific: “Languages do in fact differ considerably with regard to where the boundary between inalienably and alienably possessed items is located” (Heine, Reference Heine1997:11).

Furthermore, in German, the alienability/inalienability distinction is only loosely associated with linguistic structures. An important syntactic strategy to establish alienable possession is to use a form of predication such as in (4a). This, however, does not work easily with inalienable relations as shown in (4b) and (4c). In definite contexts, as is the case in (4b) and (4c), it is more common in our dialect data to use the adnominal constructions as exemplified in (1a-c) (see Section 4).Footnote 5

Apart from the alienability/inalienability distinction and the above-mentioned conceptual domains of possession, the empathy hierarchy (see Figure 1) also seems to play an important role when it comes to license the use of certain constructions.

In particular, the empathy hierarchy is relevant with regard to the semantics of the possessor phrase, which seem to license the use of certain constructions in relation to the above-given semantic domains of possession. It is, for example, often assumed (e.g., Zifonun, Reference Zifonun2003:102) that the adnominal possessive dative construction (DDAT POSS H) usually requires an animate possessor (D) or a possessor who/which is ranked higher on the empathy hierarchy (see Figure 1). This is indicated by the examples in (5):

As explained in Section 1—and at least for some dialect regions in Hesse (according to Kasper, Reference Kasper2017)—the empathy hierarchy needs to be expanded by the semantic category “inanimate but anthropomorphic” possessors (5d) like dolls, teddy bears, or garden gnomes (see Figure 1).

In sum, the syntactic variants to express adnominal possession are assumed to be related to the above-mentioned parameters ranging from the conceptual domains of possession over the alienability/inalienability distinction to the degree of animacy of the possessor phrase (Kallenborn, Reference Kallenborn2019; Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b; Shin, 2014). Of particular interest to our second research question is the fact that the syntactic variants for the adnominal expression of possession are in flux and assumed to be part of ongoing grammaticalization processes (Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b:63).

Therefore, in the following sections, we will take a closer look at the most widespread syntactic constructions of adnominal possession and their semantic and syntactic constraints in different geographical regions.

2.2 Adnominal syntactic variants of expressing possessive relations

The following sections focus on the description and discussion of those adnominal variants that are particularly relevant for the dialects in Austria (cf., Breuer & Bülow, Reference Breuer, Lars, Lars, Kristina and Ann-Kathrin2019:258–264; Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll & Lenz, Reference Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenzaccepted), namely, the adnominal possessive dative construction (2.2.1), pre- and postnominal von-constructions (2.2.2), and pre- and postnominal genitive constructions (2.2.3).

2.2.1 Adnominal possessive dative construction

The most prominent and most widely discussed construction to express possessive relations in German dialects is the adnominal possessive dative construction given in example (6). The construction usually consists of a dependent dative constituent ([dem] Peter in [6a]), which designates the possessor (D), as well as a possessive element in the third-person singular or plural (sein in [6]), which precedes the possessum that is the head (H) of the entire construction (Auto in [6]). Thus, unlike the other constructions, the adnominal possessive dative is restricted to the third person form of a possessor (cf., Ágel, Reference Ágel, Péter, Regina and László1993:9–11; for an exception, see Nickel, Reference Nickel and Gabriele2016:92). The possessor slot (D) can also be filled by pronouns as, for example, deictic (6b) or interrogative pronouns (6c). (For a detailed discussion of different [formal] syntactic interpretations, see Demske, Reference Demske2001; Haider, Reference Haider and Ludger1992; Rauth, Reference Rauth2014; Shin, Reference Shin2004; Weiß, Reference Weiß, Sjef, Olaf and Marika2008, Reference Weiß, Gunther and Guido2012; and Zifonun, Reference Zifonun2003.) Note that the adnominal possessive dative constructions show “a preference for definite possessors” (Nickel, Reference Nickel and Gabriele2016:92).

Despite the longstanding research interest in this construction (cf., for example, Bart, Reference Bart2020; Demske, Reference Demske2001; Kallenborn, Reference Kallenborn2019; Kasper, Reference Kasper, Michael, Markus and Jürgen Erich2015a, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b, Reference Kasper2017; Nickel, Reference Nickel and Gabriele2016; Weise, Reference Weise1898; Weiß, Reference Weiß, Sjef, Olaf and Marika2008; Zifonun, Reference Zifonun2003), no generally accepted term has been established for this type of construction. Following Kasper (Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b) and Kallenborn (Reference Kallenborn2019), we use the term “adnominal possessive dative construction.” Kasper (Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b:59) points out that the term adnominal possessive dative is a “nomenclature […] obviously based on the Standard German case system.” In the case systems of some German dialects, however, in which the genitive and dative is absent (particularly in Low German and Low Franconian dialects), the possessor phrase does not materialize as a dative (as the term suggests) but as an obliquus (‘Einheitskasus’). In contrast, most of Austria’s traditional dialects’ case systems still have a dative. Thus, it appears to be more adequate to speak of ‘adnominal possessive dative constructions’ regarding Austrian dialects.

The adnominal possessive dative construction is probably the youngest of the constructions under discussion in the history of German (see Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b), dating back to the fifteenth century (Fritze, Reference Fritze, Gerhard and Joachim1976:420,460). The construction is common in all dialects and other regional varieties of German (e.g., Behaghel, Reference Behaghel1923:638; Henn-Memmesheimer, Reference Henn-Memmesheimer1986:132–151; Kasper, Reference Kasper2017), but is considered non-standard by prescriptive grammars of German.Footnote 6 The adnominal possessive dative construction is further reported to be at the core of the concept of “possession as ownership” or alienable possession. Thus, the possessor is mostly considered to be human or at least animate (Behaghel, Reference Behaghel1923:638; Bernhardt, Reference Bernhardt1903:4; Wegener, Reference Wegener1985:49; Zifonun, Reference Zifonun2003:102). Kasper (Reference Kasper, Michael, Markus and Jürgen Erich2015a, Reference Kasper2017), however, has shown that this does not necessarily have to be the case in Rhine Franconian and Central Hessian dialects in Hesse, where inanimate but anthropomorphic possessors are possible (e.g., der Puppe ihr Fuß ‘the foot of the doll,’ see Section 1).

2.2.2 Prenominal and postnominal von-constructions

Two other important adnominal constructions for expressing semantic relations of possession are the postnominal (7a) (H von D) and prenominal von-constructions (7b) (von DH).

Possessive von-constructions were grammaticalized from formerly ablative/locative von-constructions (‘of’/‘from’ constructions), that is, these von-constructions that today express alienable and also inalienable possessive relations “make use of markers that once indicated, and in other constructions continue to indicate, spatial relations in German” (Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b:60).

In contrast to the adnominal possessive dative construction, postnominal and prenominal von-constructions are used in all varieties, registers, and speech styles (Kallenborn, Reference Kallenborn2019; Kasper, Reference Kasper2017), including both traditional dialects and standard varieties. This also seems to be the case in both the diaglossic dialect regions in the Bavarian-speaking parts and in the diglossic Alemannic regions of Austria (cf., Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll & Lenz, Reference Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenzaccepted).

Zifonun (Reference Zifonun2003:123) considers von-constructions and adnominal possessive dative constructions as “competing” variants in non-standard varieties of German with a clear complementary distribution. According to Zifonun, adnominal possessive dative constructions are used for animate possessors and von-constructions for inanimate possessors. This restriction, however, is too general, as is indicated by Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenz (Reference Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenzaccepted; see Section 2.3) and as will be shown in the findings of this paper (see Section 4). Further possible restrictions apply to prenominal von-constructions, in particular. According to the Duden Grammar (Reference Duden2016:840), they are almost exclusively used in spoken language when they refer to proper nouns. (This view, however, is challenged by Lang, Reference Lang2018). In any case, prenominal von-constructions are stylistically marked in contrast to postnominal von-constructions.

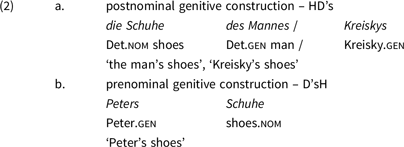

Regarding the three different conceptual domains of the concept “possession,” von-constructions can be used in all of them, as the examples in (8) illustrate:

It seems to be particularly interesting that, in contrast to adnominal possessive dative constructions (see Section 2.2.1), von-constructions can also take indefinite possessors (e.g., Das ist das Blatt von einer Eiche, ‘This is the leaf of an oak tree’).

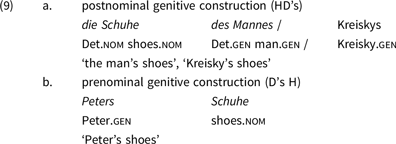

2.2.3 Pre- and postnominal genitive constructions

Even though postnominal (NP NPGEN) (9a) and prenominal genitive constructions (NPGEN NP) (9b) are often considered to have almost disappeared from non-standard varieties of German (Fleischer & Schallert, Reference Fleischer and Oliver2011:84–87), we take them into account in our study because of indications that they are still in use in some Austrian dialects (see Section 1).

Both genitive constructions are used to express alienable and inalienable possessive relations (cf., Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm and Frans2003). As we saw earlier (see Section 1), prenominal genitive constructions—even if the syntactic status of the genitive attributes is controversial (for details, see Demske, Reference Demske2001; Werth, Reference Werth2020)—are largely restricted to possessor phrases that are expressed as bare proper nouns (see Duden Grammar, Reference Duden2016:839). Syntactically, prenominal genitive attributes and determiners are mutually exclusive in the standard language, though in many dialects prenominal genitive constructions occur with articles (des Vaters Hut, lit. ‘the father’s hat’). Furthermore, prenominal genitive constructions cannot be used for partitive/meronymic relations in which the possessor is not human. In contrast, postnominal genitive constructions have less restrictions. They can be used for ownership and kinship as well as partitive/meronymic relations. With animate possessors consisting of bare proper nouns (das Auto Peters, lit. ‘the car Peter’s’), however, they appear to be at least stylistically marked.

As discussed above, some Bavarian and Alemannic dialects have preserved the prenominal genitive construction in the context of ownership and kinship relations (see Section 1).

2.3 Adnominal possession in Austria’s traditional dialects—first insights

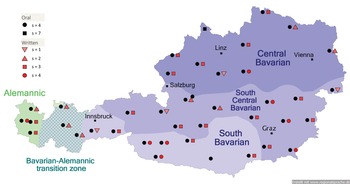

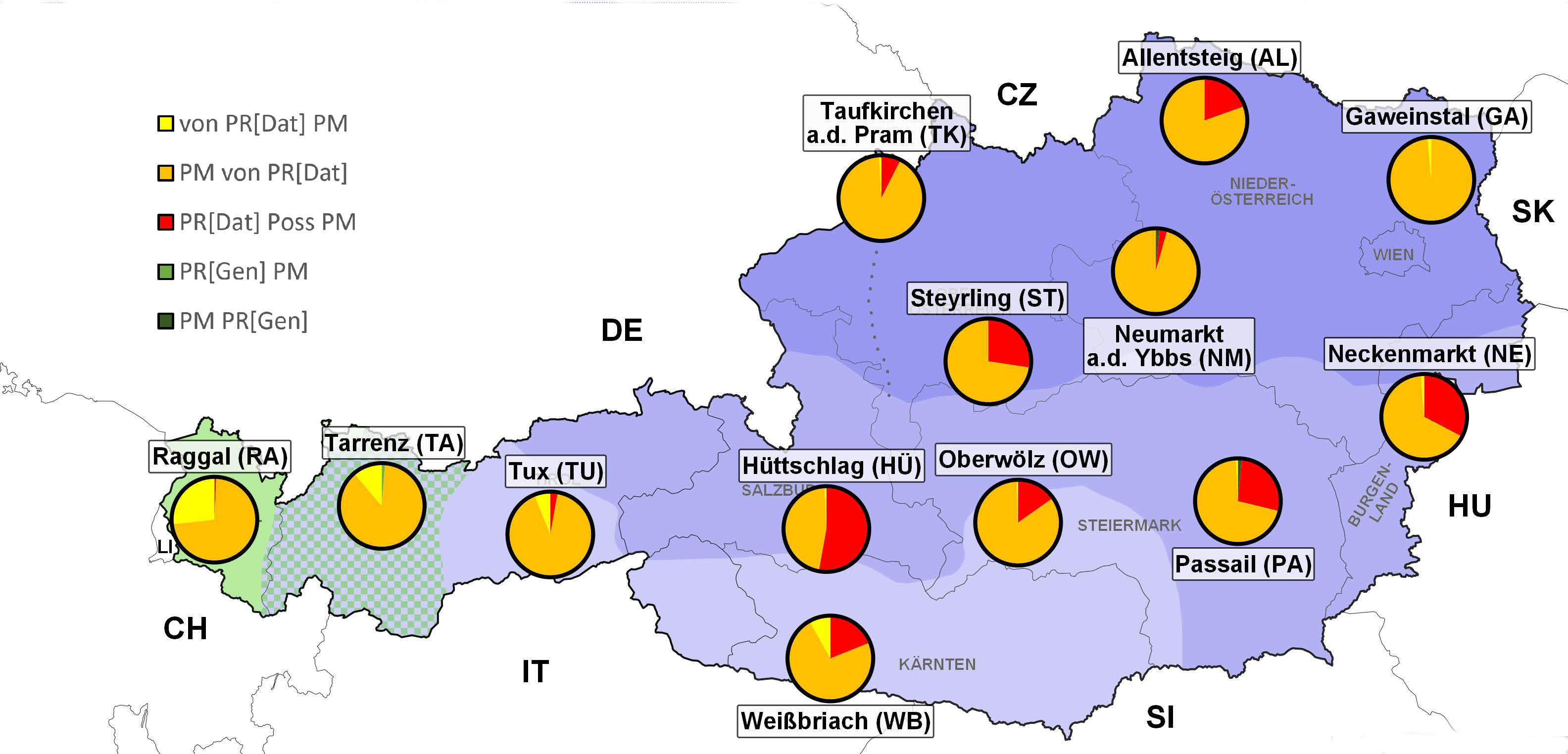

A first overview of the geographical distribution of the use of different constructions of adnominal possession in Austria can be obtained from a map of the Atlas zur deutschen Alltagssprache (AdA) (“Atlas of Colloquial German”) with data from 2012 (see Map 1).

Map 1. Use of syntactic variants to express possessive ownership relations (Elspaß & Möller, Reference Elspaß and Möller2003–).

The map shows the distribution of constructions for the phrase ‘Anna’s key’ in present-day urban colloquial German, displaying the most frequent (bigger dots) and second most frequent variants (smaller dots) per location. Data for this map were recorded via an online questionnaire for just over fifty towns and cities in Austria. The results reveal a clear west-east divide in Austria. Whereas in the west (i.e., in the states of Vorarlberg and Tyrol) the postnominal von-construction (der Schlüssel von der Anna, green dots) is reported to be used almost exclusively, in the rest of the country, except for the southern state of Carinthia, the adnominal possessive dative construction (der Anna ihr Schlüssel, pink dots) appears to be dominant at most locations.Footnote 8 Note that in both constructions, the proper noun is used with a determiner (der Anna ‘Det.dat Anna.dat’).

Evidently, an online survey on the use of colloquial language in urban areas does not say much about the language use in rural areas, let alone in traditional dialects. Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenz (Reference Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenzaccepted) provide insights into the use of different constructions of adnominal possession in rural Austria (see Map 2). They collected data from 147 informants in thirteen rural locations using laptop-supported so-called “language production experiments” (LPE; for this methodological approach, see also Breuer & Bülow, Reference Breuer, Lars, Lars, Kristina and Ann-Kathrin2019, and Lenz, Breuer, Fingerhuth, Wittibschlager & Seltmann, Reference Lenz, Ludwig Maximilian, Matthias, Anja and Seltmann2019) for different varieties (“intended base dialect” vs. “intended standard”). In the LPE dataset of Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenz (Reference Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenzaccepted) (n = 1,905 responses), the informants mostly used postnominal von-constructions (79.3%, n = 1,511) in the dialect run. 15.7% of the responses (n = 300) contained adnominal possessive dative constructions and 4.6% prenominal von-constructions (n = 88). Genitive constructions appeared only in 0.31% of cases (n = 6).

Map 2. Use of syntactic variants to express possessive ownership relations (LPE - dialect run) (Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll & Lenz, Reference Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenzaccepted:23)

Whereas the postnominal von-construction was used in all locations, the adnominal possessive dative construction appeared in all but three locations (see Map 2). Two of these three survey locations do not belong to the Bavarian area: Raggal, which is Alemannic, and Tarrenz, which is situated in the the Bavarian-Alemannic transition zone (here colored in green and in a green-blue crosshatch; for a localization of the dialect regions, see Map 3). The third location, Gaweinstal, situated close to the capital Vienna, is an exception insofar as it is the only location in the Central Bavarian dialect region showing no adnominal possessive dative construction in the LPE data. Noticeably, in the Alemannic dialect region, in which the adnominal possessive dative constructions are very rarely used, the prenominal von-constructions occur at a higher frequency than elsewhere (see Map 2). Regarding the factors age and level of education, Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenz (Reference Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenzaccepted) found no significant differences in the use of the constructions in the dialect run.

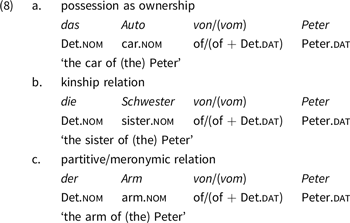

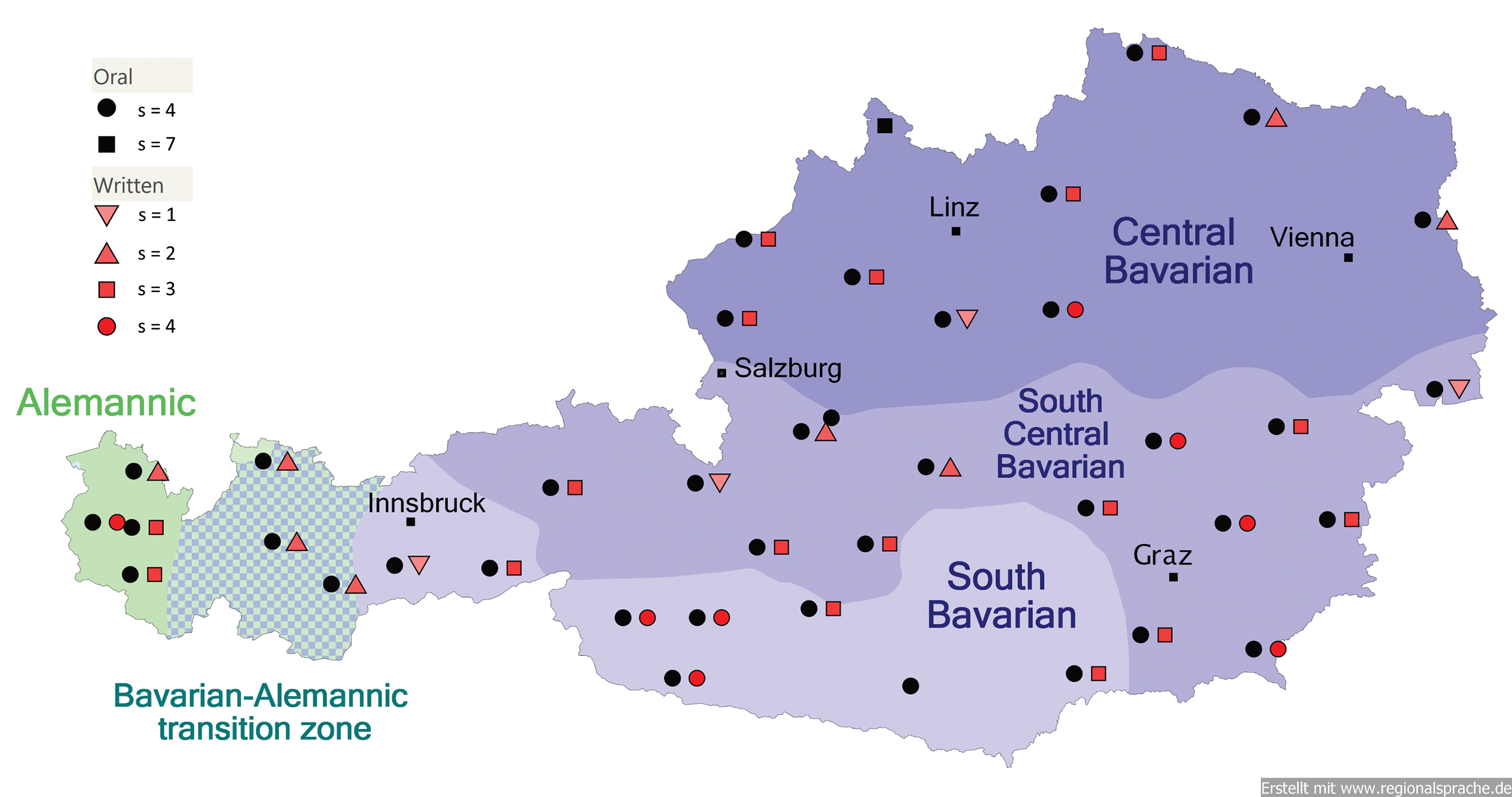

Map 3. Research locations and dialect regions (s = number of speakers)

3. Methods and data sample

The present study is based on a dialect survey that was conducted in forty small, rural villages all over Austria (see Map 3). As Map 3 indicates, most of the villages belong to the Bavarian dialect area, consisting of Central Bavarian, South Central Bavarian, and South Bavarian dialects (cf., Wiesinger, Reference Wiesinger and Herbert1983). Furthermore, seven locations are situated in the Bavarian-Alemannic transition zone and the small Alemannic dialect region in the west of Austria. Alemannic dialects differ to a large extent from most Bavarian dialects (for an overview cf., for example, Lenz, Reference Lenz, Joachim and Jürgen Erich2019).

3.1 Research design and informants

In every village, four speakers of the local dialect were surveyed.Footnote 9 Each sample consists of two older (65+ years) and two younger speakers (18–35 years), with one male and one female speaker per age group. In sum, our sample includes 162 informants. Furthermore, traditional dialectological criteria for sampling were applied (see, for example, Chambers & Trudgill, Reference Chambers and Peter1998). The older speakers can be regarded as NORM/Fs (= nonmobile, old, rural males/females). The younger dialect speakers can be characterized as almost equally immobile; they are (also) farmers or manual workers, and they were raised and have a family background in the respective location.

Two methods were used to collect data: direct dialect recordings and written questionnaires.

-

The direct dialect recordings were conducted by trained field workers based on a traditional dialect questionnaire. In the course of these interviews, the 162 informants had to complete several tasks: translation tasks, cloze tasks, and picture-naming tasks. In what follows, we focus on the translation tasks, in which the informants were asked to translate sentences from the standard language into their local dialects. In doing so, they not only had to adapt phonetic and morphological features but also syntactic features.

-

All 162 informants were also asked to complete a written questionnaire. This did not take place immediately after the direct survey because of the long duration of the recordings and in order not to overstrain the informants. Thus, they were requested to complete the questionnaire and send it back to the project team some days later. However, some informants were unwilling to complete a written questionnaire, others probably forgot about it (although having received reminders from the field workers). Despite these obstacles, a majority of 103 people from thirty-seven villages returned a completed questionnaire (see Map 3 for the number of informants per location).

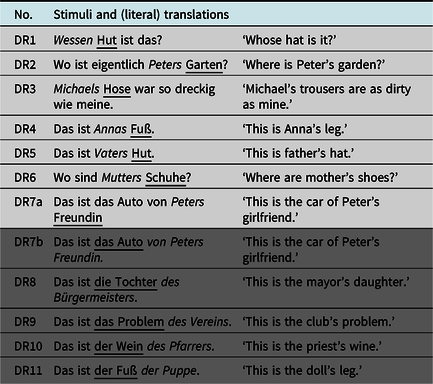

3.2 Stimuli

Table 1 shows the eleven stimuli sentences from the direct recordings (DR) chosen for the present study. The task of the informants was to translate the stimuli sentences into their local dialect. All stimuli contain at least one possessive relation, one stimulus sentence even two (DR7a, DR7b). While for the role of the possessum (see the underlined NPs in Table 1) both animate and inanimate entities are given in the questionnaire, for the role as possessor (see the italic NPs in Table 1) mostly proper names or nouns referring to humans are stipulated. The three exceptions include DR1, with an interrogative pronoun (referring to a human) as possessor, DR9, with a collective noun as possessor, and DR11, with an anthropomorphic entity as possessor.

Table 1. Stimuli sentences of the direct recordings (DR)

It is important to note that not only the semantics but also the syntactic forms of the possessor phrases differ in the stimuli: while for proper names and the terms Vater (‘father’) and Mutter (‘mother’) prenominal genitive constructions were used for the standard language stimuli (light shading), in the other stimuli postnominal genitive constructions were given (dark shading). One exception is DR7b in which the stimulus is a postnominal von-construction.

For the purpose of the present study, we additionally analyzed eight stimuli sentences from the written questionnaire (WQ) (see Table 2). All stimuli were designed as cloze tasks. The informants had to complete the beginnings of the sentences with the items in the brackets. Due to the context, all NPs in brackets should unambiguously be interpretable as either possessor (italic) or possessum phrase (underlined).

Table 2. Stimuli sentences of the written questionnaire (WQ)

Although most of the possessive relations in these stimuli coincide with those from the direct recordings (see Table 2), not all of them do (WQ1, WQ2, WQ6). It is noteworthy that, apart from two possessive relations with an anthropomorphic possessor (WQ1, WQ8), one stimulus also has an inanimate possessor (WQ2). Another difference between the direct recordings and the written questionnaire is that, in most written stimuli, the NP encoding the possessor is positioned after the NP giving the possessum (dark shading).

4. Results

In this section, we will present the results of our study. We begin by describing our findings from the direct dialect recordings (Section 4.1), which will then be compared with results from the written questionnaire data (Section 4.2). In both sections, we will start with introducing the general results before we address the stimuli-specific differences.

4.1 Direct recordings

As explained in Section 3.1, in the direct recordings (DR) the 162 informants had to translate eleven sentences containing possessive relations into their own local dialects. The total amount of stimuli is twelve, as sentence 7 comprises two possessive relations (DR7a and DR7b, see Table 1). In doing so, they mostly used the variants already explained in Section 2.2. In total, we got 1,929 responses, which we were able to include into the calculations (162*12 = 1,944 responses; fifteen responses could not be included in the analyses).

4.1.1 General findings

With 782.5Footnote 10 (41%) responses, postnominal von-constructions were used most frequently in the data, followed by adnominal possessive dative constructions with 705 (37%) responses. Somewhat surprisingly, genitive constructions occurred quite often (10%, n = 201), with prenominal genitive constructions clearly prevailing (94%, n = 189.5). Additionally, predications with gehören (‘to be owned by so./sth.’/‘to belong to so./sth.’) (5%, n = 103) and compounds (2%, n = 44.5) can be found in the data.

As Figure 2 indicates, speakers of both genders used these variants to a similar extent. Furthermore, we did not find any apparent-time effects in the data. Neither the gender differences nor the age-related differences are significant (based on Wilcoxon rank-sum tests). These findings account for stability (see Labov, Reference Labov1994:83).

Figure 2. Age and gender related differences in the direct recordings (s = number of speakers, t = number of tokens)

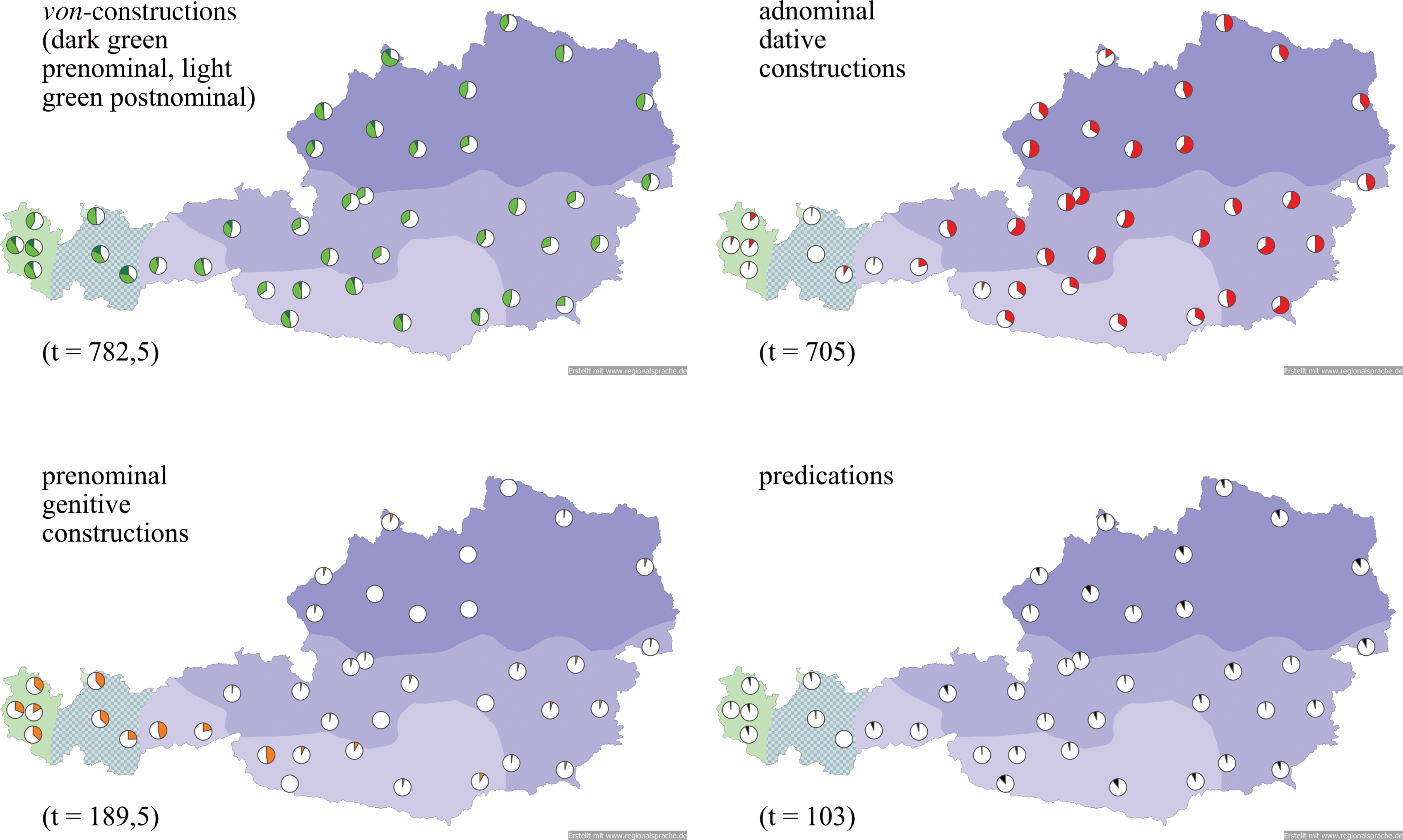

When it comes to the geographical variation of the variants, we find significant differences for most major variants. Whereas postnominal von-constructions occur in all regions quite frequently, the prenominal von-constructions are restricted to the western parts of Austria, particularly to the Alemannic and South-Bavarian dialect regions (see Map 4, top left). This also applies to the genitive constructions, which again are used more widely in the western parts of Austria (i.e., in the Alemannic and South-Bavarian dialect regions [see Map 4, bottom left]). It is noteworthy that the adnominal possessive dative constructions show an opposing geographical variation. Whereas adnominal possessive dative constructions seldom appear in the west (particularly in Vorarlberg and Tyrol), they seem to prevail in the other regions of Austria belonging to the Central Bavarian, South Central Bavarian, and South Bavarian dialect regions (see Map 4, top right). The predicative constructions, finally, show no clear geographical variation, since they occur in all regions as minor variants (see Map 4, bottom right).

Map 4. Geographical variation of different constructions of adnominal possession in direct recordings (t = number of tokens)

In sum, mainly the constructions with the possessor phrase preceding the possessum phrase are regionally distributed, leading to significant differences between the dialect regions in the west and the dialect regions in the center and east of Austria (see Table 3). In that respect, we also find a significantly negative relationship between adnominal possessive dative constructions on the one hand and prenominal genitive constructions (rs = –.641, p < .000***) and prenominal von-constructions (rs = –.473, p < .000***) on the other hand. Prenominal genitive constructions and prenominal von-constructions are neither positively nor negatively correlated.

Table 3. Significant differences between the dialect regions in the direct recordings based on Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (A = Alemannic, SB = South Bavarian, SCB = South Central Bavarian, CB = Central Bavarian)

Note that the distribution of the prenominal variants does not fully coincide with the traditional dialect regions in Austria (see Map 4). Rather, there are variants (e.g., prenominal genitive constructions; prenominal von-constructions) that are favored in the west and others (e.g., adnominal possessive dative constructions) that prevail in the east. As we will show in the next section, these spatial differences are also correlated with stimuli-specific differences.

4.1.2 Stimuli-specific differences

In Section 3.2, we already introduced the stimuli of the direct recordings (see Table 1). Figure 3 illustrates how often the various variants were used in response to the individual stimuli.

Figure 3. Stimuli-specific differences in the direct recordings (s = number of speakers, t = number of tokens)

It becomes obvious that, overall, the stimuli have to be divided into two major groups (with one exception):

-

On the one hand, six stimuli (DR2, DR3, DR4, DR5, DR6, DR7a) were predominantly translated using adnominal possessive dative constructions accompanied by using a significant proportion of genitive and prenominal von-constructions while at the same time using a low proportion of postnominal von-constructions.

-

On the other hand, there are five stimuli (DR7b, DR8, DR9, DR10, DR11) that were mostly translated using postnominal von-constructions, whereas adnominal possessive dative constructions were used only rarely and genitive constructions as well as prenominal von-constructions were hardly used at all.

-

One stimulus, DR1, seems to be an exception here since it is often translated using predicative constructions.

In order to explain these stimuli-specific differences, first we have to consider a formal factor, that is, the various formal features of the stimuli given in Table 1. What becomes evident is that those stimuli (DR2, DR3, DR4, DR5, DR6, DR7a) that were presented to the informants using a (prenominal) genitive construction tend to be translated with either an adnominal possessive dative construction, a prenominal von-construction, or a prenominal genitive construction. In contrast, those stimuli (DR7b, DR8, DR9, DR10, DR11) that were introduced using a postnominal genitive construction or, in one instance, a von-construction, were mostly translated using postnominal von-constructions. This trend indicates that the informants tend to preserve the positioning of the possessor phrase and the possessum phrase within the entire NP, which we can clearly attribute to priming effects. It is noteworthy, however, that the informants only partially echo the exact same construction.

As indicated in Section 4.1.1, language geography is a factor: while the informants from the eastern parts of Austria favor adnominal possessive dative constructions to place the possessor phrase in the first position of the entire NP, the informants from the western parts tend to use prenominal von-constructions and prenominal genitive constructions to do so. Interestingly, this geographical variation does not entirely coincide with traditional boundaries of dialect areas. In particular, informants from the South Bavarian dialect region show no uniform and consistent responses for the entire dialect area. Informants from the western parts of this region tend to favor the same variants as the informants from the Alemannic dialect region, whereas informants from the eastern parts of the South Bavarian dialect region tend to agree with the informants from the other Bavarian dialect regions in their responses.

There are some further differences between the different responses to the stimuli: as already mentioned, DR1 seems to be an exception. This may be the case because the stimulus in DR1 is an interrogative, not a declarative, sentence. Additionally, wessen (‘whose’) is encoding the possessor in DR1, that is, it is a lexeme that does not exist in the traditional dialects. This may have motivated the informants to realize very free translations without focusing on the possessive relation (e.g. Welcher Hut ist das? [‘Which hat is this?’]).

Stimulus DR7b (Das ist das Auto von Peters Freundin, ‘This is the car of Peter’s girlfriend’) also triggers an interesting pattern of responses since the informants almost exclusively used postnominal von-constructions for the translation. This might be caused by the fact that this stimulus sentence already contains another possessive relation (stimulus DR7a: Das ist das Auto von Peters Freundin). This possessive relation was predominantly translated by applying an adnominal possessive dative construction (e.g., Peter seiner Freundin, lit. ‘Peter his girlfriend’) or a prenominal genitive construction (e.g., Peters Freundin, lit. ‘Peter’s girlfriend’), while no prenominal von-constructions occur. A possible explanation for this is that a prenominal von-construction would cause an immediate succession of von (*das Auto von vom Peter der Freundin, lit. ‘the car of of Peter’s girlfriend’), which appears to be ungrammatical. The use of two consecutive postnominal von-constructions, however, is not ungrammatical (das Auto von der Freundin vom Peter, lit. ‘the car of the girlfriend of Peter’), though rarely used. Thus, the informants may have wanted to avoid a repetition of von-constructions in the same sentence. The fact that they also avoided using a possessive dative construction in DR7b ((dem) Peter seiner Freundin ihr Auto,Footnote 11 lit. ‘[the] Peter his girlfriend her car’) may be due to the fact that the focus of the entire sentence is the possessor phrase of stimulus DR7b (Freundin ‘girlfriend’), which becomes focused through the postnominal von-construction (e.g., das Auto von / vom Peter seiner Freundin, lit. ‘the car of [the] Peter his girlfriend’). Thus, the results indicate that the information structure of the entire NP could be relevant for the encoding of possessive structures.

This may also account for other differences illustrated in Figure 3. In contrast, neither the various conceptual domains of possession nor the distinction regarding alienability/inalienability (see Section 2.1) have any clear effects. To give an example, the stimuli encoding kinship relations triggered both relatively high and relatively low response rates of adnominal possessive dative constructions (see for example DR7a vs. DR8). The same applies to “possession as ownership” relations (see for example DR2 vs. DR10).

Interestingly, the inanimate anthropomorphic possessor Puppe (‘doll’) in stimulus DR11 (Das ist der Fuß der Puppe, ‘This is the doll’s leg’) is sometimes encoded using an adnominal possessive dative construction, though not very often. This might be explained by the low position of “inanimate but anthropomorphic possessors” (like ‘doll’) on the empathy hierarchy (see Section 2.1, Figure 1). When it comes to human possessors, we can see a major difference between possessors expressed by proper names and kinship expressions (DR2, DR3, DR4, DR5, DR6, DR7a) compared to those expressed by common nouns (e.g., DR8, DR10). Since only proper names and a few kinship expressions allow for prenominal genitive constructions in the standard language, this difference coincides with the effects of the position of the possessor phrase mentioned above.

In order to both deepen and validate the findings made in this section, we will compare the results of the direct dialect recordings with the written questionnaire data presented in the following section.

4.2 Written questionnaire

In addition to the direct dialect recordings, we also tested the target variables with a written syntax questionnaire. All stimuli (see Table 2) were designed as cloze tasks. The informants had to complete stimuli sentences with items that were presented in brackets (see Section 3.2) in their local dialect. Thus, in order to syntactically express the possessive relations given in the stimuli sentences, the 103 informants who filled in the syntax questionnaire mainly drew on the variants introduced in Section 2.2. In total, 846 responses were collected and analyzed.

4.2.1 General findings

In the questionnaire data, the informants used more von-constructions (66%, n = 557.5) than in the direct recordings, with an even bigger proportion (95%) of postnominal von-constructions (n = 527.5). The second most common variant is again the adnominal possessive dative construction (27%, n = 225.5), though it is used less often than in the direct recordings. All other variants are not very frequent; the proportion of genitive constructions (3%, n = 24) is only about a third as high as in the direct recordings, with, again, a much greater proportion (79%, n = 19) of prenominal genitive constructions. Hence, somewhat surprisingly, the written stimuli (in standard German) did not trigger a higher frequency of answers that would only echo the structure of written standard German forms (i.e., mainly genitive constructions). The proportion of predications (2%, n = 18) and other variants (3%, n = 21) in the written questionnaire is very low.

In sum, postnominal von-constructions clearly outweigh all other variants in the written questionnaire with again no significant differences between both age groups and genders (based on Wilcoxon rank-sum tests; see also Figure 4).

Figure 4. Age and gender related differences in the written questionnaire (s = number of speakers, t = number of tokens)

Due to the dominance of postnominal von-constructions, the geographical variation of the variants in the written questionnaire is less obvious. Nevertheless, there are certain differences, as Map 5 illustrates.

Map 5. Geographical variation of the variants in the written questionnaire (t = number of tokens)

As we expected, postnominal von-constructions can be found throughout the entire research area (see Map 5, in light green, top left), while prenominal von-constructions are more restricted. As in the direct recordings, prenominal von-constructions are primarily used in the western parts of Austria (see Map 5, in dark green, top left). The same applies to the prenominal genitive constructions (see Map 5, bottom left), while the adnominal possessive dative constructions are more frequent in the Central Bavarian and South Central Bavarian dialect regions (see Map 5, top right). Again, the predicative constructions have no clear geographic focus (see Map 5, bottom right). Thus, as Table 4 shows, the indirect written data confirm the geographical variation already indicated in the direct recordings (see Section 4.1.1), again with a significantly negative correlation between the use of adnominal possessive dative constructions and prenominal genitive constructions (rs = –.431, p < .000***). The use of other variants is uncorrelated. Whether the stimuli-specific differences in the results of the written questionnaire are similar to the results of the direct recordings will be considered in the following section.

Table 4. Significant differences between the dialect regions in the written questionnaire data based on Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (A = Alemannic, SB = South Bavarian, SCB = South Central Bavarian, CB = Central Bavarian)

4.2.2 Stimuli-specific differences

Similar to the direct recordings, the informants vary greatly in the written questionnaire data in expressing the different possessive relations given in the eight stimuli sentences (see Figure 5). Having said this, it can also be observed that the variants the informants used to express the exact same possessive relations differ substantially between the direct recordings and the written questionnaire (apart from WQ3a and WQ3b, see below). At first glance, however, there is no clear trend. In WQ4 (Das ist [Problem] [Verein], ‘It is [problem] [club]’), when compared to DR9 (Das ist das Problem des Vereins, lit. ‘This is the club’s problem’), more adnominal possessive dative constructions are used (e.g., Das ist dem Verein sein Problem, lit. ‘This is the club his problem’). The same accounts for WQ7 (Das ist [Tochter] [Bürgermeister], ‘She is [daughter] [mayor]’) and DR8 (Das ist die Tochter des Bürgermeisters, lit. ‘This is the daughter mayor’s’), respectively. For the stimuli WQ5 (Das ist [Hut] [Vater], ‘This is [hat] [father]’) and DR5 (Das ist Vaters Hut, ‘This is father’s hat’), the results are exactly the opposite.

Figure 5. Stimuli-specific differences in the written questionnaire (s = number of speakers, t = number of tokens)

One possible explanation is the presented order of the possessor phrase and the possessum phrase within the stimuli in the direct data and hence the priming effects in the interviews. This, at least, would explain why the direct “counterparts” of WQ7 and WQ4 (possessor phrase preceding the possessum phrase in the direct recordings) show a higher amount of adnominal possessive dative constructions, while the direct “counterpart” of WQ5 (possessum phrase preceding the possessor phrase in the direct recordings) shows a lower amount of adnominal possessive dative constructions. Apparently, the presented order of the possessor phrase and the possessum phrase within the stimuli plays a crucial role in the direct recordings due to the spontaneity and immediacy of the translations in the interview situation. Although it may seem that there are also priming effects in the written questionnaire data—in most stimuli the possessum phrase precedes the possessor phrase and hence there are more postnominal von-constructions in the indirect data—these effects cannot fully account for the differences shown in Figure 5. To explain the data in the written questionnaire, we have to consider other factors.

Only stimulus WQ3b (Das ist [Peter] [Freundin] [Auto]) was used predominantly with adnominal possessive dative constructions (e.g., Das ist das Auto von/vom Peter seiner Freundin, lit. ‘This is the car of (the) Peter his girlfriend’) and a considerable amount of genitive constructions (e.g., Das ist das Auto von Peters Freundin, ‘This is the car of Peter’s girlfriend’). This can be explained, first, by the fact that the proper name (Peter) in the possessive phrase (like the kinship term Vater ‘father’ in WQ5) ranks highly on the empathy hierarchy (see Figure 1). Second, it is noteworthy that the stimulus that has a similar structure in the direct recordings (see DR7b) is also used with the highest proportion of adnominal possessive dative constructions and a relatively high proportion of prenominal genitive constructions. Likewise, in the written questionnaire it is again the other possessive relation ([Auto] [Peter]) (WQ3a) that is rather rarely expressed as a prenominal construction. As in DR7b, our informants preferred postnominal von-constructions in WQ3a (e.g., Das ist das Auto von/vom Peter seiner Freundin). With this in mind, the patterns regarding WQ3a and WQ3b can also be attributed to the structural and pragmatic constraints already given in Section 4.1.2 for DR7a and DR7b.

What is more obvious in the data of the written questionnaire is the relevance of the empathy hierarchy: all three stimuli that have an inanimate possessor come with a rather low proportion of adnominal possessive dative constructions.

Nevertheless, the data show a difference between the stimuli that have an inanimate but anthropomorphic possessor (WQ1, WQ8), and the stimulus that has an inanimate and non-anthropomorphic possessor (WQ2). Regarding the latter, only once an adnominal possessive dative construction was used. This finding seems to confirm Kasper’s (Reference Kasper, Michael, Markus and Jürgen Erich2015a, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b) claim that adnominal possessive dative constructions can be used for ‘inanimate but anthropomorphic’ possessors but not for ‘inanimate’ entities in the possessor phrase.

The ranking illustrated in Figure 5 provides evidence for our assumption that the empathy hierarchy cannot fully account for the variation in the encoding of possessive relations. It leaves some open questions, such as why WQ4, which has no human possessor in a narrow sense (Verein, ‘club’), shows up as the stimulus with the second highest proportion of adnominal possessive dative constructions? As in the results for the direct recordings (see Section 4.1), neither the conceptual domains of possession nor the alienability/inalienability distinction can fully explain these differences.

5. Discussion

The analysis in Section 4 revealed several characteristics of adnominal constructions expressing semantic relations of possession in Austria’s traditional dialects. It is noteworthy that the direct and the indirect survey show very similar results with regard to the spatial distribution of the variants as well as their use per age group and gender. It is therefore not surprising that we found correlations in the responses of those 103 informants of whom both direct recordings and written questionnaires are available. To give an example: informants who tend to use prenominal genitive constructions in the direct recording also do so when answering the questionnaire (rs = .614, p < .000***). Accordingly, we can summarize that the use of translation tasks in the direct recordings and cloze tasks in the written questionnaires has no marked influence on the general results of this study and, ultimately, the consistency of the core findings in both task types provide evidence for the validity of the results.

In this section, the major findings will be discussed in greater detail. First, we address the geographical variation and the question of continuity and change. Second, we focus on possible explanations for the stimuli-specific differences that extend beyond the obvious priming effects in the direct recordings. Thereby, we aim to highlight the question of why each of the observed dialects allow for prenominal placement of the possessor.

5.1 Geographical variation

Regarding the geographical variation of the syntactic variants to express possessive relations, we can identify similarities and differences between the eastern and western dialect regions of Austria. The postnominal von-construction as well as the (much less frequent) predications seem to be evenly distributed all over Austria. Differences could be identified regarding the use of the adnominal possessive dative construction, the prenominal von-construction, and the prenominal genitive construction. While the informants from the western parts of Austria (i.e., in the Alemannic and some South Bavarian dialect regions) seem to favor prenominal von-constructions and prenominal genitive constructions to keep the possessor phrase in the first position of the entire NP, the informants from the central and eastern parts (i.e., in the Central Bavarian, South Central Bavarian, and some South Bavarian dialect regions) prefer adnominal possessive dative constructions. The latter use the prenominal von-constructions and the prenominal genitive constructions only very rarely or not at all.

We conclude that wherever adnominal possessive dative constructions occur, prenominal von-constructions and prenominal genitive constructions are not used and vice versa (see Sections 4.1.1 and 4.2.1). This is in line with Bart’s (Reference Bart2020) findings for Highest Alemannic dialects in Walser German in Switzerland, where prenominal genitive constructions prevail while adnominal possessive dative constructions are only marginally used.

Interestingly, the geographic distribution of the variants does not exactly coincide with the traditional dialect boundaries. This becomes particularly apparent for the South Bavarian dialect region where we have (besides postnominal von-constructions) prenominal von-constructions and prenominal genitive constructions in the west and adnominal possessive dative constructions in the east. This inconsistency within the South Bavarian dialect region may not be overly surprising, as the boundaries of dialect regions were determined on the basis of phonetic and phonological variants in traditional dialectological approaches. It is well known that syntactic variables do not necessarily coincide with phonetic and phonological variables because they tend to have a wider scope (see, for example, the discussion in Glaser, Reference Glaser2014). The west-east opposition in our data is further in line with Scheutz’s (Reference Scheutz2016) results for the South Bavarian dialects in South Tyrol. Scheutz (Reference Scheutz2016:66) reports a high number of prenominal genitive constructions for South Tyrol. The question, of course, remains whether the occurrence of these genitive constructions manifests relicts of earlier and more widespread structures in Austria’s traditional dialects or innovations due to contact with varieties of Standard German.

Considering that there are no apparent-time effects in our data, we can assume that the prenominal genitive construction is a rather stable feature in the language use of our informants. A flat pattern within an apparent-time analysis indicates either stability or communal change (Labov, Reference Labov1994:83). Regarding the findings of Bart (Reference Bart2020) on Alemannic dialects in Switzerland and Scheutz (Reference Scheutz2016) on South Bavarian dialects in South Tyrol, it is more likely that we are dealing with stability and continuity rather than with communal change. These findings also indicate that prenominal genitive constructions have survived in a broader area in High German dialects as has been reflected in the research literature so far (see also Lipold, Reference Lipold1976:264). Postnominal genitive constructions, however, can be regarded as largely diminished in the traditional dialects of the speakers (Fleischer & Schallert, Reference Fleischer and Oliver2011:84–85).

5.2 Prenominal possessive constructions, accessibility hierarchy, and referential anchoring

As already mentioned, the main regional differences occur with those constructions in which the possessor phrase is preceding the possessum phrase. This order could be elicited via priming effects quite often in the direct interviews, though it also occurs unprimed in both the direct and the indirect data. It is remarkable that every dialect in Austria has constructions that allow for this order, either in the form of the adnominal possessive dative construction or in the form of the prenominal von-construction and the prenominal genitive construction. This suggests that there is some function attached to this order. In what follows, we will argue and provide evidence that “referential anchoring” (Langacker, Reference Langacker, Taylor and MacLaury1995; Taylor, Reference Taylor1996) combined with the concept of “accessibility” (Bock & Warren, Reference Bock and Richard1985) is the key to explaining the positioning of the possessor within the entire possessive construction.

What all the prenominal variants seem to have in common is that they are restricted to phrases containing “prototypical” possessors (i.e., an animate or inanimate but anthropomorphic entity). Kasper (Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b) explains this pattern by linking animacy and agentivity. He identifies animate entities as intentional agents and, therefore, controllers. This makes them “‘real’ possessors, i.e., those executing control” (Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b:93). Kasper (Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b) subsequently proposes two conflicting principles: on the one hand, there is a “syntactic tendency to develop a H > D order within the noun phrase” (Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b:93) so that the possessum precedes the possessor; on the other hand, there is also a “language users’ cognitive strive for identifying the initiator/controller of any event as soon as possible.” Following from that, only entities with a high rank in the animacy hierarchy identified as controllers allow for the prenominal placement of the possessor.

If the assumption is correct that the link between agentivity and animacy accounts for the placement of the possessor phrase, one would expect “ownership relations” to be frequently expressed by prenominal constructions. In contrast, in “kinship relations” or “partitive/meronymic relations” they should be rather infrequent since the semantic feature of “control” does not play an evident role here (see for example the link between alienability and the various possessive relations given in Section 2.1). As our data indicate, this is obviously not the case. Ownership relations do not trigger a higher amount of prenominal possessive constructions, neither in the direct recordings (see Section 4.1.2) nor in the written questionnaire data (see Section 4.2.2). Differences in agentivity, linked with differences in animacy, generally cannot account for the actual stimuli-specific differences, at least if we do not assume, as Kasper (Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b) does, that possessive relations containing an animate possessor are generally interpreted as ownership relations.

This leads to another possible explanation, which Kasper (Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b) mentions, namely, definiteness. If we look at the historical development of possessive constructions in German, we can find that prenominal possessive constructions “‘climb up’ the referential expressions scale” (Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b:92; see also, for example, Demske, Reference Demske2001), so that today, in general, only “those referents whose identity is determined easiest in discourse remain in prenominal position” (Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b:92). Ultimately, a possible explanation for why all dialects allow for the prenominal placement of the possessor phrase has to consider definiteness as well as animacy. Both categories are highly interwoven (see, for example, Croft, Reference Croft2002:128–56).

One key concept employed to explain this interrelatedness is that of “accessibility.” Like animacy and definiteness, accessibility is not binary but a hierarchy defined by “the ease with which the mental representation of some potential referent can be activated in or retrieved from memory’” (Bock & Warren, Reference Bock and Richard1985:50). Both definiteness and animacy play a major role in constituting accessibility, since definiteness refers to the accessibility of concepts in a given context, whereas animacy accounts for the inherent accessibility of entities by virtue of their intrinsic semantic properties (see, for example, Vogels & Van Bergen, Reference Vogels and Geertje2013). What is common for accessible expressions (i.e., entities ranked highly in the animacy hierarchy or concepts placed highly in the definiteness hierarchy) is that they are more topical; this is why there is a tendency to place them earlier in a sentence (see, for example, Givón, Reference Givón1979). If we reconsider that the prenominal possessive constructions are restricted more or less to both definite expressions and animate entities, we can simply state that prenominal possessive constructions are limited to both inherently and contextually highly accessible concepts. All observed dialects seem to allow such concepts to be placed earlier in discourse.

Therefore, we argue that the concept of “referential anchoring” offers a plausible explanation for what we found in the data. In a nutshell, the concept of referential anchoring (for details, see Langacker, Reference Langacker, Taylor and MacLaury1995; Taylor, Reference Taylor1996) stipulates that the possessor phrase helps to access the referent of the possessum phrase in a possessive construction, hence serving as an “anchor” or “reference point.” In order to ensure optimal cognitive processing, the “anchor” has to precede the “anchored,” since “[t]he speaker […] invites the hearer to first conceptualize (‘establish mental contact with’) the one entity (the possessor), with the guarantee that this will facilitate identification of the target entity (the possessee)” (Taylor, Reference Taylor1996:17). To serve as good “anchors” and to facilitate the identification of the possessum phrase, the possessor phrase has to be highly accessible. Taylor (Reference Taylor1996:210–21) identifies two properties that make concepts accessible—which we already discussed above—namely, “discourse-conditioned topicality” and “inherent topicality.” Ultimately, we believe that “accessibility” and “referential anchoring” can serve as good explanations of our findings.

First, it accounts for the fact that these constructions favor proper names and kinship expressions. Proper names and kinship expressions are ranked highest in the “Monolexemic Possessor Accessibility Hierarchy” (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Maling, Skarabela, Kersti, David and Alan2013:11). Second, it explains why there are no obvious differences between the conceptual domains of possession since they are not accompanied by differences in accessibility. Third, it explains why inanimate but anthropomorphic entities behave “unusually.” It can be argued that they are, by virtue of their “quasihuman” properties, more accessible and thus better “anchors” than non-anthropomorphic entities (see Vogels, Krahmer & Maes, Reference Vogels, Krahmer and Maes2013).

Referential anchoring finally explains why prenominal possessive constructions are merely optional in all contexts in the observed dialects. Whereas animacy is an inherent property of an entity, accessibility is not. It is a context-dependent feature and thus driven by pragmatics. In order to find more evidence to support the assumption that both accessibility and referential anchoring account for possessive relations in Austrian dialects, it will be necessary to investigate more natural speech data. In any case, our data point in this direction. As shown in Section 4.1.2, those stimuli that were presented to the informants using a prenominal genitive construction tend to be translated with a prenominal possessive construction. One can claim that the possessor phrase in those stimuli is contextually more accessible through its placement when compared to the other stimuli in the direct recordings and to the stimuli that are analogously built in the written questionnaire. From this perspective, accessibility could explain why priming effects occur in our data that only seldomly echo the exact same construction but the same positioning of the possessor phrase.

6. Conclusion

This paper studied the geographical variation of syntactic constructions of adnominal possession and their development in Austria’s traditional dialects. We set out to explore the structure of this variation (Research Question 1). Based on data from direct recordings of 162 speakers from forty villages in Austria and on written questionnaire data from 103 of these speakers from thirty-seven villages, the analyses resulted in three main findings.

First, dialect speakers in Austria use a range of constructions in which a possessor phrase precedes the possessum information, in particular, the adnominal dative construction (or “adnominal possessive dative”), the prenominal genitive construction, and the prenominal von-construction. The only construction in the dialects where the possessum is followed by the possessor is the postnominal von-construction. Unlike in written Standard German, dialect speakers in Austria do not use the postnominal genitive construction.

Second, the use of the prenominal von-construction and adnominal dative construction shows a clear west-east opposition. The adnominal dative construction is frequently employed in the Bavarian dialect regions in the center and east of Austria but is hardly present in the west (i.e., in the Alemannic dialect regions and the Alemannic-Bavarian transition zone). In contrast, the prenominal von-construction is limited to the western dialect regions. This is largely in line with the findings of Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenz (Reference Goryczka, Wittibschlager, Korecky-Kröll and Lenzaccepted). Furthermore, the relatively few instances of (possibly archaic) prenominal genitive constructions are used exclusively in the regions in the west, especially in those dialect regions that are considered particularly archaic (cf., Bart, Reference Bart2020; Scheutz, Reference Scheutz2016). As we did not find any significant apparent-time effects in the data, this geographical pattern seems to be relatively stable.

Third, the geographic distribution of these syntactic features does not entirely follow traditional dialect boundaries, which are built on phonological features (e.g., in the South Bavarian dialect region). Thus, there is reason to believe that the dialect map of Austria based on syntactic features would be partly different from the “traditional” dialect map.

We then tried to find semantic and pragmatic factors to explain the main syntactic patterns in geographical variation (Research Question 2). In particular, we investigated the nature of the constructions highlighted above (i.e., constructions where a possessor precedes a possessum). We re-examined explanations that highlight the role of semantic properties of the possessor, such as animacy and agentivity, and the ranking of the possessor on the empathy hierarchy (cf., Kasper, Reference Kasper, Chiara, Agnes and Doris2015b). In contrast to such semantic approaches, we focused our attention on pragmatic factors (Research Question 3). In particular, we proposed to look at the concepts of accessibility and referential anchoring as the keys to an explanation for the syntactic sequence that is common to all three constructions mentioned. We provided evidence that it is urgent to shift the emphasis on the semantic properties of the possessors to their contextual role, hence their discursive-pragmatic properties. They could also explain the optional status of prenominal constructions in structures of adnominal possession in Austria’s traditional dialects.

Acknowledgments

The research for the present article was conducted within the framework of the project “Variation and change of dialect varieties in Austria (in real und apparent time)” by the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF), grant no. F 06002, as part of the Special Research Program “German in Austria” (SFB F 60). We would like to thank Dominik Wallner and Jan Luttenberger for collecting and Marlene Hartinger for annotating the data. Our thanks also go to Simon Kasper and Alexander Werth for helpful comments on an earlier draft of the paper.