The private health insurance market in Israel offers two voluntary products: the first, offered by the non-profit health plans (HPs), is referred to as supplemental insurance (SI); the second, provided by for-profit insurers, is known as commercial insurance (CI). Both types of cover play a complementary role, covering benefits excluded from the National Health Insurance (NHI) scheme such as dental health care for adults. They also play a supplementary role, providing faster access to care, greater choice of provider and improved amenities (in the private sector), and extended cover of services included in the NHI, such as more physiotherapy or psychotherapy sessions compared with what the NHI offers. The Israeli private health insurance market’s main distinctive feature is the very high levels of population coverage and dual coverage (almost all people who own CI also own SI).

We observe two trends in the health care market: (i) the decrease in the public share of health spending in the last two decades, followed by a sharp growth in private activity and private health insurance coverage; and (ii) the growth of the private health insurance market accompanied by various negative impacts on the public system’s financial sustainability, accessibility and availability of services and quality of care.

Analysis of the Israeli case highlights the complexity of integrating statutory and broad private (voluntary) health insurance. Integration efforts have created a range of, sometimes conflicting, incentives and disincentives, which have implications for achieving public policy goals such as choice, extended coverage, equity, solidarity and curbing government spending while maintaining a strong publicly financed health system.

Key features of the health system

Historical background

The structure of the Israeli health system was put in place before the establishment of the State of Israel (1948). Four non-profit HPs,Footnote 1 established between 1920 and 1940 by political parties or trade unions, insured their members and provided medical services. In 1948, the Ministry of Health took on the role of planning, regulation and supervision of the HPs, and began to provide selected health services and run hospitals (Reference Gross, Anson and TwaddleGross & Anson, 2002). Although health insurance was voluntary, by 1995 almost all citizens (96%) were insured, mainly by Clalit, which had a 62% share of the market. The HPs were only loosely regulated by the Ministries of Health and Finance, and could set their own benefits and premiums and reject applicants.

Between 1948 and 1995, the structure of the health system was repeatedly debated by government committees, but major stakeholders opposed reform, fearing nationalization of the health system and loss of powerFootnote 2 (Reference YishaiYishai, 1982; Reference Gross, Anson and TwaddleGross & Anson, 2002; Reference Schwartz, Doron, Davidovitch, Bin Nun and OferSchwartz, Doron & Davidovitch, 2006). In the 1980s, high inflation rates and economic recession led to a policy of reduced government spending, which affected Clalit in particular, as it had been highly dependent on the financial aid allocated by earlier Labour coalition governments. By 1988, Clalit had accumulated a deficit of US$700 million, which was endangering the stability of the health system (Reference ChinitzChernichovsky & Chinitz, 1995). Consequently, the government appointed a commission of inquiry into the financial crisis facing Clalit, inequality in service provision, labour unrest and public dissatisfaction with HPs’ services (Reference GrossGross, 2003; Reference Rosen, Bin Nun, Bin Nun and OferRosen & Bin Nun, 2006). The commission’s recommendationsFootnote 3 included:

NHI legislation to regulate competition among the HPs and increase the financial stability of Clalit; transforming hospitals into competing self-financed autonomous non-profit entities; and reorganizing the Ministry of Health to reduce its involvement in service delivery and strengthen its policy-making, planning and monitoring functions (Reference Gross, Anson and TwaddleGross & Anson, 2002).

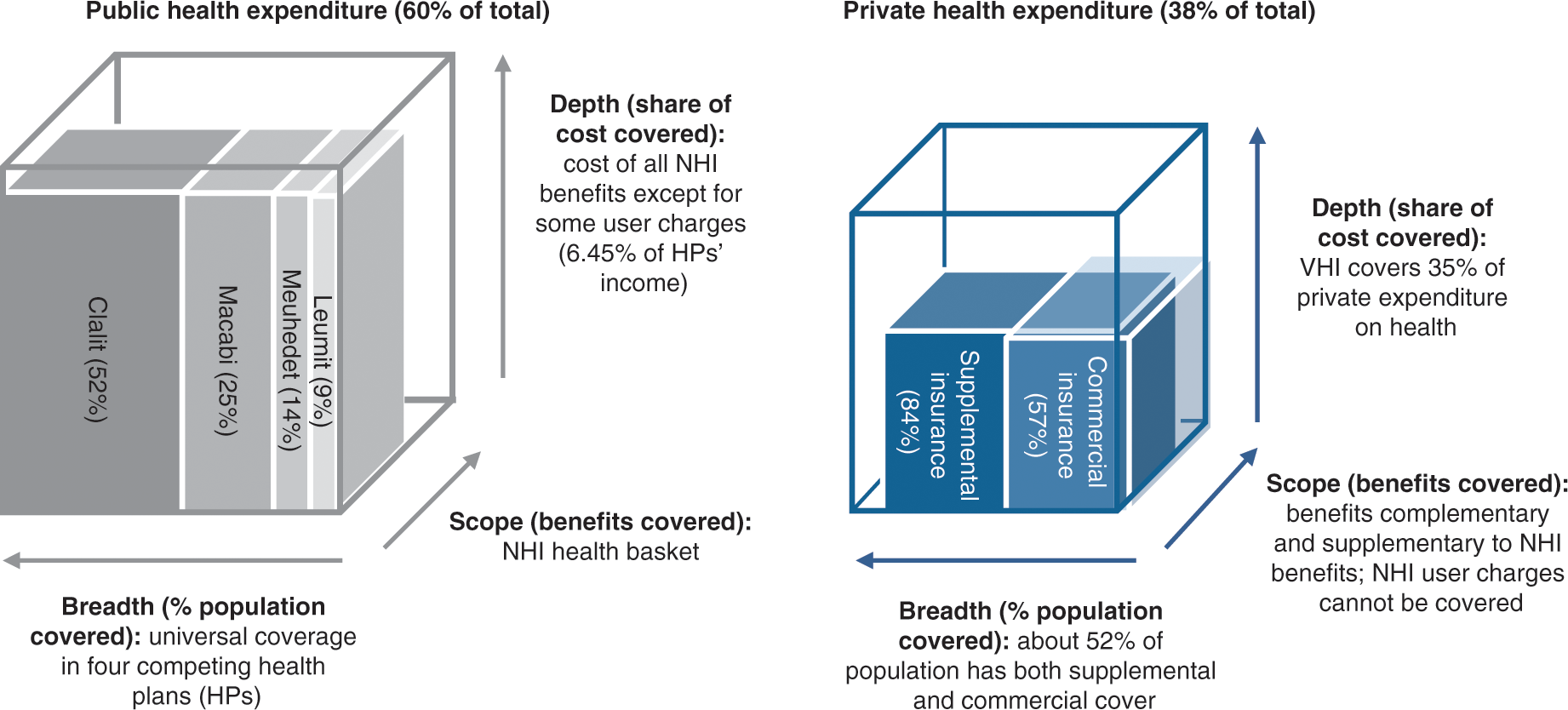

The development of NHI

The NHI Law came into effect in January 1995, adopting many elements of Reference EnthovenEnthoven’s (1993) managed competition model (Reference ChinitzChinitz, 1995; Reference Gross, Rosen and ShiromGross, Rosen & Shirom, 2001; Reference Gross, Anson and TwaddleGross & Anson, 2002; Reference GrossGross, 2003). It stipulates that all Israeli residentsFootnote 4 are entitled to a specified package of benefitsFootnote 5 that includes primary, secondary and tertiary care, emergency and preventive care, listed medications, diagnostic procedures and medical technologies. The Ministries of Health and Finance update the benefits package annually.Footnote 6 All residents must register with one of the competing non-profit HPs, which are forbidden by law to reject applicants, and six times a year they may choose to change HP (it is possible to make up to two switches over a period of 1 year). In 2013, Clalit had the largest market share (52.2%), followed by Maccabi (24.8%), Meuhedet (13.6%) and Leumit (9.0%) (Reference Horev and KeidarHorev & Keidar, 2014). Within the public system, HPs provide care (listed in the NHI benefits package) in the community and purchase inpatient and outpatient care from hospitals (about 80% of hospitals’ revenues come from services sold to HPs). Within the private system there are two types of private health insurance, with a broad coverage and a significant overlap (see Fig. 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Public and private health insurance coverage in Israel, 2016.

Alongside the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Finance plays a major role and must approve all Ministry of Health decisions that have budgetary implications. The two ministries share responsibility for monitoring the HPs’ financial performance (Reference Gross and HarrisonGross & Harrison, 2001; Reference Gross, Anson and TwaddleGross & Anson, 2002); setting the NHI annual budget, setting official price lists and physicians’ salaries and so on (Reference Brammli-GreenbergBrammli-Greenberg et al., 2016). Other powerful players with considerable influence over national policy-making include the Israel Medical Association and hospital managers.

NHI revenue collection, pooling of funds and allocation to HPs

The government determines the level of funding for the NHI benefits package, adjusting the previous year’s budget to take account of demographic changes, inflation and new health technologies. Most (88%) of the NHI budget is divided among HPs prospectively through a capitation formula that takes into account the insured members’ age, gender and place of residence (periphery or centre of the country). Another 5.5% of the funds are allocated to the HPs based on the number of members with one of five severe illnesses.Footnote 7 The remaining 6.45% is raised by the HPs retrospectively through user charges for outpatient medications and specialist consultations (Ministry of Health, 2014a).

Purchasing services and payment mechanisms

Tertiary care: Of the 45 general hospitalsFootnote 8 in Israel, 18 are publicly owned and account for 57% of Israel’s acute-care hospital beds. Another 40% of beds (16 general hospitals) are operated by non-profit organizations. The remaining 11 are for-profit hospitals, are smaller and operate only 3% of the beds. Hence, non-profit hospitals account for approximately 97% of the acute beds and 92% of acute admissions (Ministry of Health, 2014b). HPs pay for outpatient clinics and emergency departments in hospitals on a fee-for-service basis and for inpatient care via length of stay and activity-based payments. Prices are set by the government by a joint Ministry of Health and Ministry of Finance committee that sets maximum price lists for all hospital services (Reference Brammli-GreenbergBrammli-Greenberg et al., 2016). HPs contract with other providers (for example, diagnostic centres) predominantly on the basis of negotiated fee-for-service arrangements.

Primary and secondary care: The salaries of primary care physicians employed at HPs’ clinics and of hospital physicians and other professionals in the public sector (for example, nurses, pharmacists) are mainly determined through collective bargaining with the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Health. Contracts are used to remunerate independent physicians on a capitation basis. Payment methods of HPs for community-based specialists may also include a fee-for-service per procedure or a flat rate per shift. Some physicians take on private work on a fee-for-service basis. Most dentists work independently and set their own fee-for-service rates (Reference Rosen, Waitzberg and MerkurRosen, Waitzberg & Merkur, 2015).

Health expenditure

The proportion of GDP devoted to health care has fallen from 8.4% in 2001 to 7.4% in 2015, mainly due to cost control and rationing mechanisms. For example, in the area of outpatient care, HPs negotiate prices with pharmaceutical and medical technologies companies, negotiate salaries with contracted physicians and other professionals, and also control regional supply of workforce and services and can use waiting times as a rationing mechanism (Reference Brammli-Greenberg and WaitzbergBrammli-Greenberg & Waitzberg, 2017). HPs also negotiate price discounts with hospitals.

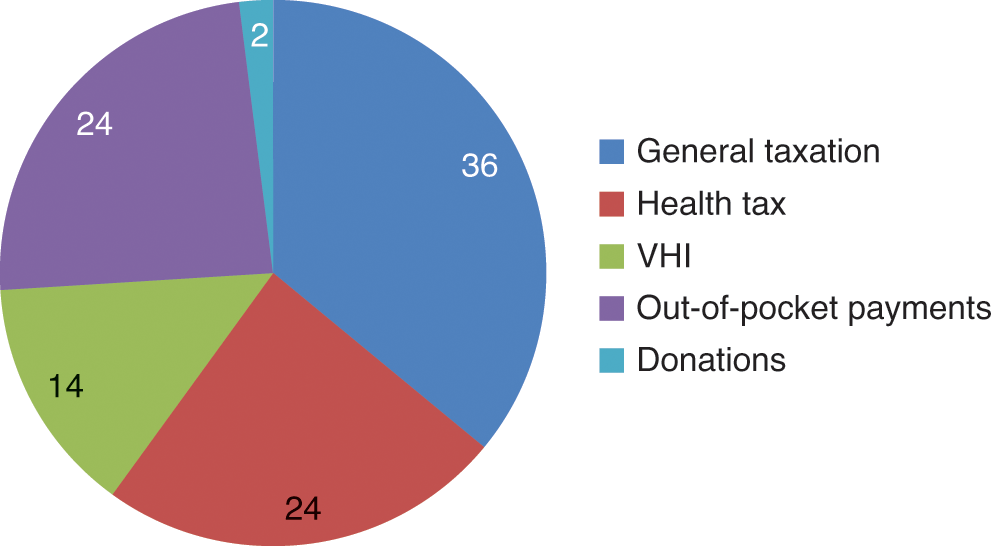

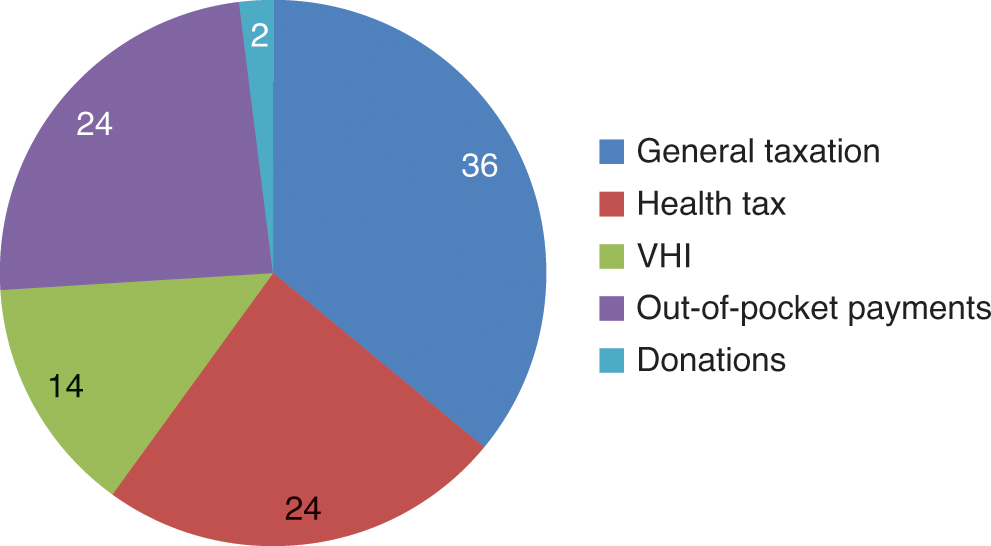

Rationing in the area of inpatient care includes supply-side restraints (for example, on workforce, number of hospital beds) employed by the Ministries of Health and Finance and cost containment measures such as maximum price-lists set by the government, caps on hospitals’ annual revenues from each HP and stringent control of salaries. The public share of health care funding decreased from 75% of total spending on health in 1996 to 60% in 2015 (see Fig. 8.2) and it is one of the lowest among OECD countries.

From Fig. 8.2 we can see that the dedicated income-related health tax funds only account for a quarter of total spending on health in Israel. The remaining public funding comes from government funds, the amounts of which are decided every year, therefore making this source somewhat volatile. Private spending is significant, especially the out-of-pocket component, described below.

Out-of-pocket payments

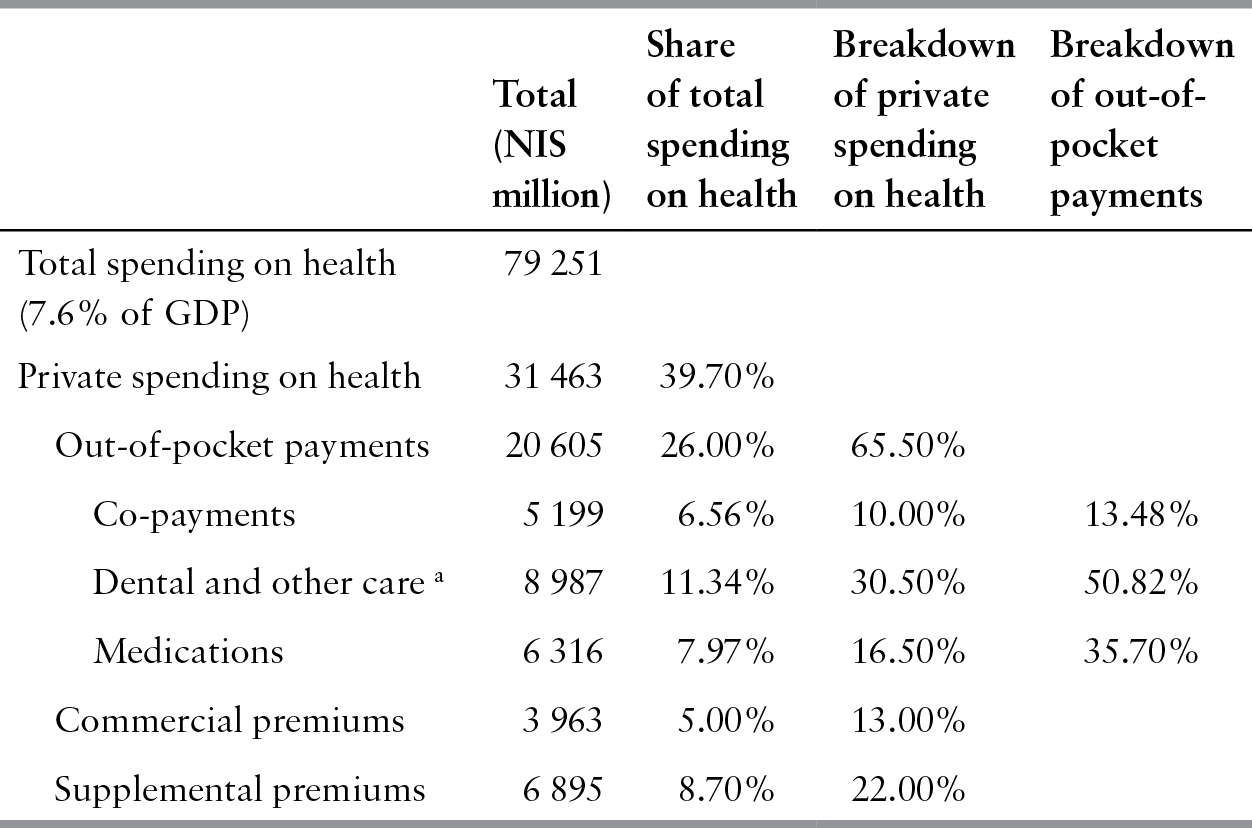

Out-of-pocket payments in Israel consist of user charges paid to HPs for visits to specialists and coinsurance for medications; and spending on services not included in the health basket. For example, households pay privately for dental care for people aged 12 and over, prostheses, hearing aids, medications not included in the medications basket, and services in the private sector such as private hospitals and private physicians (see Table 8.1 for a detailed breakdown of the private spending on health). Although private health insurance does not cover user charges, it covers services provided in the private market. Survey data from 2012 indicate that 35% of households’ health spendingFootnote 9 was for private health insurance premiums, 25% for dental care, 16% for medications and 24% for other services (Reference Horev and KeidarHorev & Keidar 2014).

Table 8.1 Breakdown of private health care expenditure in Israel, 2013

| Total (NIS million) | Share of total spending on health | Breakdown of private spending on health | Breakdown of out-of-pocket payments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total spending on health (7.6% of GDP) | 79 251 | |||

| Private spending on health | 31 463 | 39.70% | ||

| Out-of-pocket payments | 20 605 | 26.00% | 65.50% | |

| Co-payments | 5 199 | 6.56% | 10.00% | 13.48% |

| Dental and other care a | 8 987 | 11.34% | 30.50% | 50.82% |

| Medications | 6 316 | 7.97% | 16.50% | 35.70% |

| Commercial premiums | 3 963 | 5.00% | 13.00% | |

| Supplemental premiums | 6 895 | 8.70% | 22.00% |

Notes: NIS: New Israeli Shekel.

a Glasses, medical accessories, etc.

Overview of the private health insurance market

Market role, size and regulation

Supplemental insurance

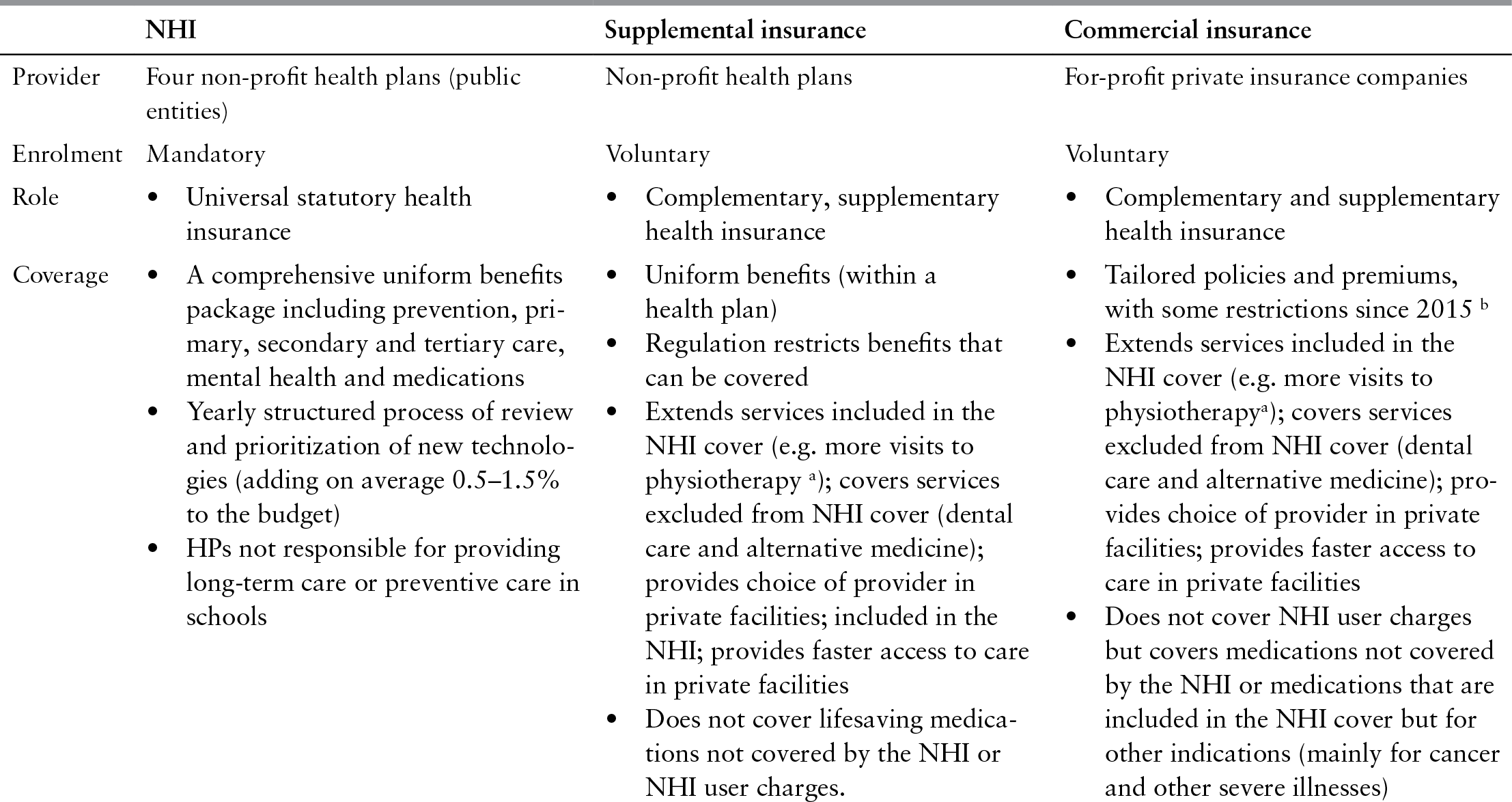

The NHI Law (State of Israel, 1994: Clause 10) allows the HPs to offer SI in addition to the mandatory NHI benefits package, and these are supervised by the Division for Regulating HPs at the Ministry of Health (see Table 8.2).

Table 8.2 Key features of the National Health Insurance and private health insurance in Israel, 2017

| NHI | Supplemental insurance | Commercial insurance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provider | Four non-profit health plans (public entities) | Non-profit health plans | For-profit private insurance companies |

| Enrolment | Mandatory | Voluntary | Voluntary |

| Role |

|

|

|

| Coverage |

|

|

|

| Terms and premiums |

|

|

|

| Regulation | Ministry of Health and Ministry of Finance |

Ministry of Health

|

Insurance Commissioner

|

Notes: HP: health plan; NHI: national health insurance

a These services are provided in private facilities. Services included in the NHI cover can also be provided in the private sector (for example, a private physiotherapist working under contract with an HP) or in HP facilities (for example, a physiotherapist directly employed in an HP facility).

b These restrictions include the requirement on commercial insurers to offer a so-called standard policy (since 2015) and charge mandatory user charges (since 2016).

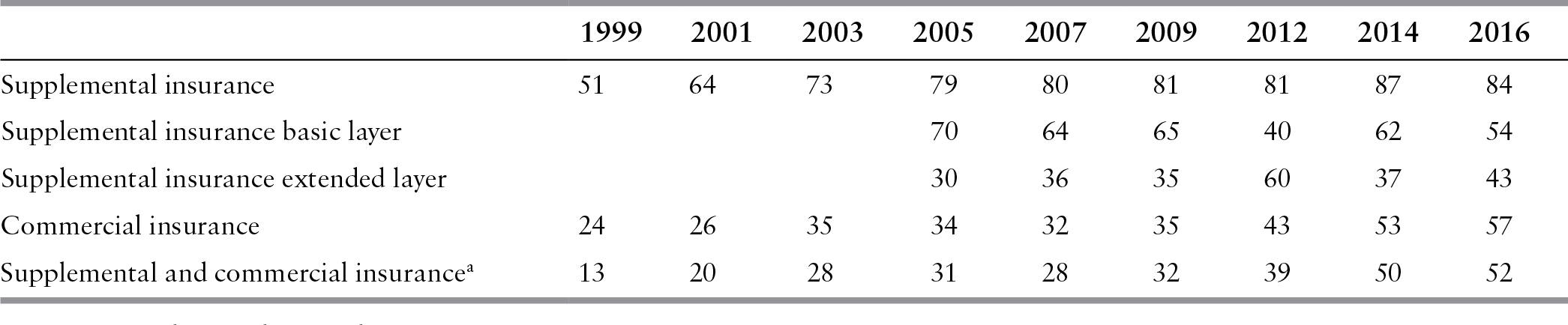

Table 8.3 Share of the adult population (22+) with private health insurance in Israel, 1999–2016

| 1999 | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplemental insurance | 51 | 64 | 73 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 81 | 87 | 84 |

| Supplemental insurance basic layer | 70 | 64 | 65 | 40 | 62 | 54 | |||

| Supplemental insurance extended layer | 30 | 36 | 35 | 60 | 37 | 43 | |||

| Commercial insurance | 24 | 26 | 35 | 34 | 32 | 35 | 43 | 53 | 57 |

| Supplemental and commercial insurancea | 13 | 20 | 28 | 31 | 28 | 32 | 39 | 50 | 52 |

Notes: Self-reported data.

a The share of adult population with supplemental insurance reflects ownership of at least one supplemental layer (basic or extended plan).

The Ministry of Health oversees benefits, premiums and user charges, as well as the financial stability of SI, approving their annual budgets and actuarial reports. The Ministry also regulates the interface with NHI benefits: first, to ensure that HPs do not give preference to SI members (for example, SI cannot cover shorter waiting times or offer an extended choice of provider at HP facilities; however, this is allowed in private clinics); and second, to ensure that SI compensates the NHI budget for use of HP facilities and staff.

Commercial Insurance

Commercial insurance is offered by private insurers and is regulated by the Insurance Commissioner at the Ministry of Finance. As for other insurance types, the Commissioner oversees policies to ensure the financial stability of insurers and protect consumer rights (through fair pricing and proper disclosure). Since the NHI legislation in 1995 and the subsequent growth of the commercial market, the Insurance Commissioner has strengthened regulation to protect consumer rights for this type of health insurance (see below).

A reform initiated in 2015 aims to increase transparency and enhance market competition, and recently additional regulation was set to limit the growth of the private provision and private insurance sectors. For example, a law stipulates that a physician who has started treating a publicly funded patient cannot provide that patient with a privately funded service during a period of at least 4–6 months (although, the physician can refer the patient to another doctor in the private system). Another law created a “standard policy” in the CI market with uniform coverage and uniform premiums by age groups for surgeries and specialists consultations only. For a detailed description of the reform see Table 8.4 and HSPM (2015, 2016).

Market structure

Residents can purchase SI from their HP only. Coverage ratesFootnote 10 are generally high, rising from 37% of the adult population in 1998 to 65% in 2001 and reaching 84% in 2016 (Reference Gross, Brammli-Greenberg and WaitzbergGross, Brammli-Greenberg & Waitzberg, 2008; Reference Brammli-GreenbergBrammli-Greenberg et al., 2019,). Coverage is also high among vulnerable population groups, with the exception of low-income individuals and Arabs.Footnote 11

Commercial insurance is offered mainly by five insurers, who account for 95% of commercial premiums. There are two types of policy-owners in the commercial market: (i) people who buy their policies directly from an insurer for a risk-rated premium based on age, gender and pre-existing conditions; (ii) organizations (for example, employers, labour unions) who purchase group policies for their members for a community-rated premium, reflecting the risk level of the group. The CI group policies have recently gained market share and are concentrated in the hands of two companies.Footnote 12, Footnote 13 In 2016, 57% of the adult population had CI. However, only 5% had CI alone; 52% had both SI and CI (see Table 8.3). The shares of adult populations owning CI are lower among vulnerable groups, especially lower-income individualsFootnote 14. Multivariate analysis reveals that the likelihood of having both types of cover is higher among younger people, highly educated people, those with high incomes and Hebrew speakers. Over half (53%) of those who have CI have a group policy (Reference Brammli-GreenbergBrammli-Greenberg et al., 2019)

The share of the Israeli population with private health insurance coverage has grown rapidly in the last decade. This growth was the major driver of growth in private spending on health: between 2002 and 2011 household monthly spending on SI and CI as a percentage of total household expenditure increased by, respectively 70% and 90% (Ministry of Health, 2012). Payments for private health insurance premiums (both supplemental and commercial) increased by more than 100% between 2005 and 2013, compared with an average increase of 18% in other insurance sectors. Per person spending on health funded by private health insurance skyrocketed by 50% between 2006 and 2011, increasing much faster than the average growth of 15% among OECD countries (see Fig. 8.3). Israel ranks third among OECD countries according to the share of population covered by private health insurance (after France and the Netherlands) (Ministry of Health, 2014d). Israel has also one of the highest shares of private spending in total spending on health among OECD countries (40% in Israel compared with 28% for OECD countries on average; OECD, 2017). In 2014, private health insurance represented about 35% of household expenditures on health, growing from 17% in 2000 (see Fig. 8.4).

Figure 8.3 Expenditure on private health insurance in Israel in per capita purchasing power parity US$ (2006 = 100), 2006–2013

Figure 8.4 Household expenditure on private health insurance in Israel (premiums and co-payments) as a share of total household expenditure on health, 2000–2014

According to the Ministry of Health, the private health insurance market is not achieving the goal of financing health care privately while reducing out-of-pocket payments: household spending on health has not changed over the last decade except for the sharp increase in spending on private health insurance premiums (Ministry of Health, 2012). Along with the increase in the share of private health insurance policy-holders in the adult population in the last decades, we have witnessed an expansion of dual coverage: 52% of the adult population own the two types of private health insurance; 92% of those who own CI own also SI, and 62% of those who own SI own also CI (Reference Brammli-GreenbergBrammli-Greenberg et al., 2019). It is worth noting that 100% of private health insurance owners are covered also by the NHI.

Private health insurance policy terms

Supplemental insurance

Since 1998, HPs have been forbidden to reject any applicants for SI, or limit coverage due to pre-existing conditions. Each HP may decide which services to include in its supplemental plan and determines its premium rates, which can differ only by age. Changes in the terms of SI policies are approved by the Ministry of Health and apply to all members. Premiums are based on yearly actuarial calculations, taking into account the benefits covered and the risk profile of members. Cover is provided for as long as the member pays the premium (those who have ceased paying can re-enrol, but will then face waiting times for services).

Health plans offer their members a choice of two SI layers: a basic plan and an extended plan with a higher premium. They also offer a group long-term care insurance (LTCI) policy, for which they contract with commercial insurers, who set premiums based on actuarial calculations (Reference 298Brammli-Greenberg, Gross and MatzliachBrammli-Greenberg, Gross & Matzliach, 2007). SI plays a complementary and a supplementary role in the health system. To date, it can provide: (i) services that are not included in the NHI benefits package (for example, adult dental care or alternative medicine); (ii) services that are covered by NHI, but only to a limited extent (for example, in vitro fertilization (IVF) and physiotherapy); (iii) care purchased from private providers that enhance choice and provide faster access or improved facilities.

Health plans use selective contracting to lower costs. They also impose user charges and waiting periods for SI benefits. Charges vary by service and may reach thousands of new Israeli shekels for major procedures (surgery, transplants, treatment abroad and fertility treatment). Waiting periods also vary by service up to a maximum of 24 months. Comparison of the SI benefits offered by each of the HPs reveals that they are similar in terms of the scope of services covered (Reference 298Brammli-Greenberg, Gross and MatzliachBrammli-Greenberg, Gross & Matzliach, 2007).

Commercial insurance

Commercial insurance also plays a complementary and a supplementary role in the health system; insurers are free to cover any medical service and offer several coverage options, including coverage for: (i) medical expenses such as surgeries and visits to specialists in Israel; implants and special procedures overseas; medicines (35% of CI health premiums in 2015), compensation for severe diseasesFootnote 15 (for example, receipt of a fixed sum, set at the insurer’s discretion, if the insured develops a severe illness such as cancer) (9%), (ii) LTC (39%) and (iii) dental care (6%). Each insurer offers several policies for each of these options (Ministry of Finance, 2015a).

Enrolment in CI is dependent on medical underwriting and, in individual policies, premiums are fully adjusted for risk (age, gender and health status) and pre-existing conditions. The exception is the standard policy for medical expenses introduced in 2015, in which premiums are standardized for age and sex groups, but insurers can also exclude individuals with medical conditions. Group premiums are lower than individual premiums for the same level of coverage, and usually less profitable. CIs offer access to private providers who are in the insurance network. Mandatory user charges for CI were stipulated by the Ministry of Finance since 2016 to reduce moral hazard.Footnote 16 Plans may involve qualifying periods and waiting times for receipt of service. Commercial insurers may offer customers incentives to use their SI cover first so that CIs only pay part of the cost, even though premiums were calculated for the full cost.

Market development and public policy

Development of the SI market

In the mid-1980s, the HPs responded to growing consumer dissatisfaction and the decline in government financial support by providing compulsory SI cover for an additional nominal premium (see Table 8.4). SI included a uniform package for all members, offering indemnity cover (rather than benefits in kind) for expensive new technologies (for example, transplants, life-saving surgery abroad, IVF) (Reference Cohen and BarneaCohen & Barnea, 1992; Reference 299Gross and Brammli-GreenbergGross & Brammli-Greenberg, 1996). Maccabi, which had offered voluntary as well as compulsory SI for decades,Footnote 17 extended its voluntary cover to include LTC, consultations with private physicians, private surgery and discounts for dental care (Reference Kaye and RoterKaye & Roter, 2001). In 1994, Meuhedet also introduced a voluntary plan covering LTC in addition to its compulsory plan.

The enactment of the 1995 NHI Law led to a significant expansion of the SI market. Under the new law, the HPs could offer only voluntary SI, for services not included in the NHI benefits package. The law stipulated that the NHI benefits package would include all the services provided by Clalit in both its core and compulsory SI covers, requiring Clalit to develop an entirely new voluntary SI. The other HPs made their compulsory SI voluntary and automatically transferred their members from the compulsory to the voluntary plan. Those who did not want SI had to notify the HP to dropout of the plan. This default registration resulted in very high rates of SI take-up (89% in Maccabi, 82% in Meuhedet and 50% in Leumit, compared with only 16% in Clalit’s plan in 1995) (Reference 299Gross and Brammli-GreenbergGross & Brammli-Greenberg, 1996).

Policy-makers allowed the HPs to sell SI cover alongside NHI in response to pressure from Maccabi and Meuhedet in the run-up to the NHI Law, to compensate them for an anticipated fall in revenue. Maccabi and Meuhedet’s membership base was relatively young and wealthy, their revenue from the new capitation formula would have been lower than it had been before the introduction of the NHI Law. Allowing them to sell SI reduced their opposition and facilitated parliamentary approval of the NHI Law (Reference GrossGross, 2003).

From 1995 to 1997, the structure of the private health insurance market became the focus of intense public debate over whether the HPs should be allowed to manage voluntary cover themselves or whether it should be provided by commercial insurers only, forcing the HPs to contract with them for their SI. Commercial insurers lobbied for this option, which was also supported by the Insurance Commissioner, who was concerned about the financial viability of SI managed by HPs (who had accrued large deficits in the past). The Ministry of Health and some academic shapers of public opinion also thought SI should be separated from the HPs, emphasizing its potential to compromise equality. Conversely, the HPs argued that SI would enhance equality by making better services accessible to a large share of the population (Reference Gross and Brammli-GreenbergGross & Brammli-Greenberg, 2001).

The regulations governing Israel’s SI market were drafted in 1998 (State of Israel, 1998). They aimed to design SI to gain from integrating private funding into the public system, while minimizing any negative impact on solidarity and equality, and to find an arrangement that would benefit the HPs and commercial insurers. As a result, the HPs were permitted to manage SI as separate financial entities with balanced accounts; SI would only provide benefits in kind and HPs must offer open enrolment and community-rated premiums (differentiated by age only); and LTCI would be provided exclusively by commercial insurers, who had the capacity to manage actuarial reserves, thereby safeguarding commercial market share. One of the most important changes brought about by the 1998 regulations was to allow SI plans to offer supplementary cover of services covered by the NHI by using private providers, that is, private consultation, private surgery, which meant enhanced choice of provider and reduced waiting times.

Despite the regulations in place, public debate over the structure of the SI market continued. Debate focused mainly on equality; on the separation of the financial management of SI and NHI benefits so that NHI funds would not indirectly subsidize supplemental business, and on the fact that eligibility waiting periods for supplemental cover might limit consumers’ ability to change HP (switching rates are low, at around 1.5% annually) (State of Israel, 2002; Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research, 2003, 2007). Regulation of SI has evolved in response to these concerns.

A 2002 regulation stipulated that income from SI would compensate the HPs’ NHI budget retroactively for the use of infrastructure and staff, so that NHI would not subsidize supplemental business. The Ministry of Health rules (Ministry of Health, 2005) include the following provisions: (i) SI annual expenses should not exceed annual revenue and premiums may be adjusted to that end without prior Ministry of Health approval; (ii) transfer of funds from the NHI budget to the SI budget is prohibited; (iii) there should be a strict separation in accounting and financial management of NHI and SI budgets; (iv) if SI benefits from administrative or other services charged to the NHI budget, it should compensate NHI for its share of the expenses (each HP has discretion to define these rates); (v) temporary SI excess revenue can be transferred to cover NHI deficits as a loan. A regulation introduced in 2010 abolished eligibility waiting periods for those who change HP. This was initiated by the Ministry of Health in response to the State Comptroller’s annual report, which criticized SI as a barrier to inter-plan mobility (State Comptroller, 2007).

The debate on the inclusion of life-saving medications

An ongoing debate that remains a central concern is whether the SI should cover life-saving medications. In 2007, the Ministry of Health approved new supplemental policies covering life-saving and life-extending medications.Footnote 18 These benefits were added to the extended layer of the SI plans, triggering intense public debate (Reference Gross and Brammli-GreenbergGross & Brammli-Greenberg, 2007). Due to Israel’s priority-setting process for medications, based on cost-effectiveness analysis, some of these medications cannot be included in the NHI benefits package and are only available on a private basis (Reference ShaniShani et al., 2000; Reference Shemer, Abadi-Korek and SeifanShemer, Abadi-Korek & Seifan, 2005).Footnote 19

The proponents of the inclusion of these medications in the SI cover claim that it can provide access to important medications that the public budget would not cover to a broad range of individuals; and it can increase the attractiveness of SI. The opponents of this policy argue that the vulnerable population that does not own SI will have no access to those medications, and it is a regressive way of funding. Moreover, once a medication is offered by the SI, the government may consider it less important to provide it through the NHI health basket.

Moreover, adding these benefits to SI cover put the HPs in direct competition with commercial insurers, particularly as they could offer cover more cheaply than commercial insurers. The latter therefore lobbied against the benefit extension. The Ministry of Health and the Knesset (Israeli parliament) also opposed it on the grounds that it would: (i) lead to inequality in access to health care; (ii) bind members to their HPs due to the relatively long waiting periods for eligibility; and (iii) weaken public pressure on the Ministry of Finance to add new medications to the NHI benefits package. The Ministry of Finance also feared that the change would increase total spending on health (Reference Gross and Brammli-GreenbergGross & Brammli-Greenberg, 2007).

Following this public debate, in 2008 the HPs were forbidden to include life-saving and life-extending medications in SI plans and the approval previously granted by the Ministry of Health was rescinded (State of Israel, 2008). After further heated debate, the Knesset’s Welfare and Health Committee approved the legislation. However, it ruled that the prohibition should be conditional on a substantial increase in public funding for NHI benefits over a 3-year period to compensate people for being unable to access these medications through SI.

The debate came back to the public agenda in 2015 when the Minister of Health declared that it is willing to allow the inclusion of such medications in the SI cover.

Development of the commercial market

The CI market was established in Mandatory Palestine in 1933. A single insurance company (Shiloach) marketed substitutive health policies chiefly as an alternative to HP services for the wealthy, providing indemnity coverage for primary, secondary and tertiary care purchased from private providers (Reference Kaye and RoterKaye & Roter, 2001). In the 1980s, the perceived deterioration in services provided by the HPs was accompanied by a proliferation of insurers entering the health market. By the early 1990s, a large number of firms (relative to the population’s size) were active (43 Israeli and 23 foreign insurance companies), although about 75% of the market was in the hands of six Israeli insurance groups, which provided more than 20 different health products (Reference Cohen and BarneaCohen & Barnea, 1992).

A 1990 survey indicated that 0.5% of the population had commercial substitutive cover and 13% had CI in addition to their HP membership. The CI market expanded significantly after the introduction of NHI, alongside the expansion of the supplemental market, which had raised consumers’ awareness of the benefits of purchasing additional cover. Commercial insurers understood the market’s potential – their health cover is extremely profitableFootnote 20 – and invested resources in marketing their own competing products.

Since 1995 there have been significant changes in the basic features of CIs, partly due to restrictions in the NHI benefits package and regulation of SI; partly due to direct competition with SI; and partly due to regulation of the commercial market. Insurers have developed new policies and new companies have entered the market. The health insurance share of total CI premium income has grown from under 5% in 1986 to 14% in 2006. The scope of benefits offered has also expanded. In 1991, most policies insured against terminal diseases and transplants (catastrophic risk) and only two companies covered private surgery and hospitalization in Israel and abroad. By 1996, most policies offered all of these things as well as LTC cover, other services covered by NHI or supplemental benefits (for example, IVF, ambulatory procedures, alternative medicine), and some services not covered by NHI or SI (for example, cosmetic surgery) (Reference 299Gross and Brammli-GreenbergGross & Brammli-Greenberg, 1996).

More recently, there has been a decrease in marketing of CI as an alternative to SI cover and an increase in marketing of CI as a supplement to SI, including through financial incentives. The prevalence of dual coverage has therefore risen from 5% in 1995 to 22% in 2001 and 52% in 2016 (Reference Brammli-GreenbergBrammli-Greenberg et al., 2019). CI has become an additional layer of insurance (with almost all of those who have CI having SI as well; see Table 8.2) rather than an alternative to SI, resulting in less direct competition between the two parts of the market.

Over time the commercial insurers’ marketing strategy shifted from selling health policies as part of life insurance packages to selling independent health policies with individually tailored benefits. Insurers also developed uniform policies, similar to the HPs’ supplemental plans, to attract group sales among trade unions and large employers (Reference 299Gross and Brammli-GreenbergGross & Brammli-Greenberg, 1996). These changes in marketing strategy combined with changes in the regulation of SI led to increased diffusion of CI in the Israeli population.

Commercial insurance is a very profitable product, with claims ratio of 58% in 2015 (46% for individual policies and 93% for group policies) and an annual (average) increase of 15% in premiums payments (Ministry of Finance, 2016). With people claiming SI coverage first (and having difficulties claiming CI coverage), it seems that CI is not being useful for those who have it (Reference Brammli-GreenbergBrammli-Greenberg et al., 2014; Ministry of Health, 2014d). Yet, CI coverage (and dual CI and SI coverage) has increased sharply in the last decade (see section on dual coverage below). The latest regulations from 2015 and 2016 (see Table 8.4) have attempted to limit dual coverage, curb growth in private health insurance coverage and reverse the trend of increasing private spending on health.

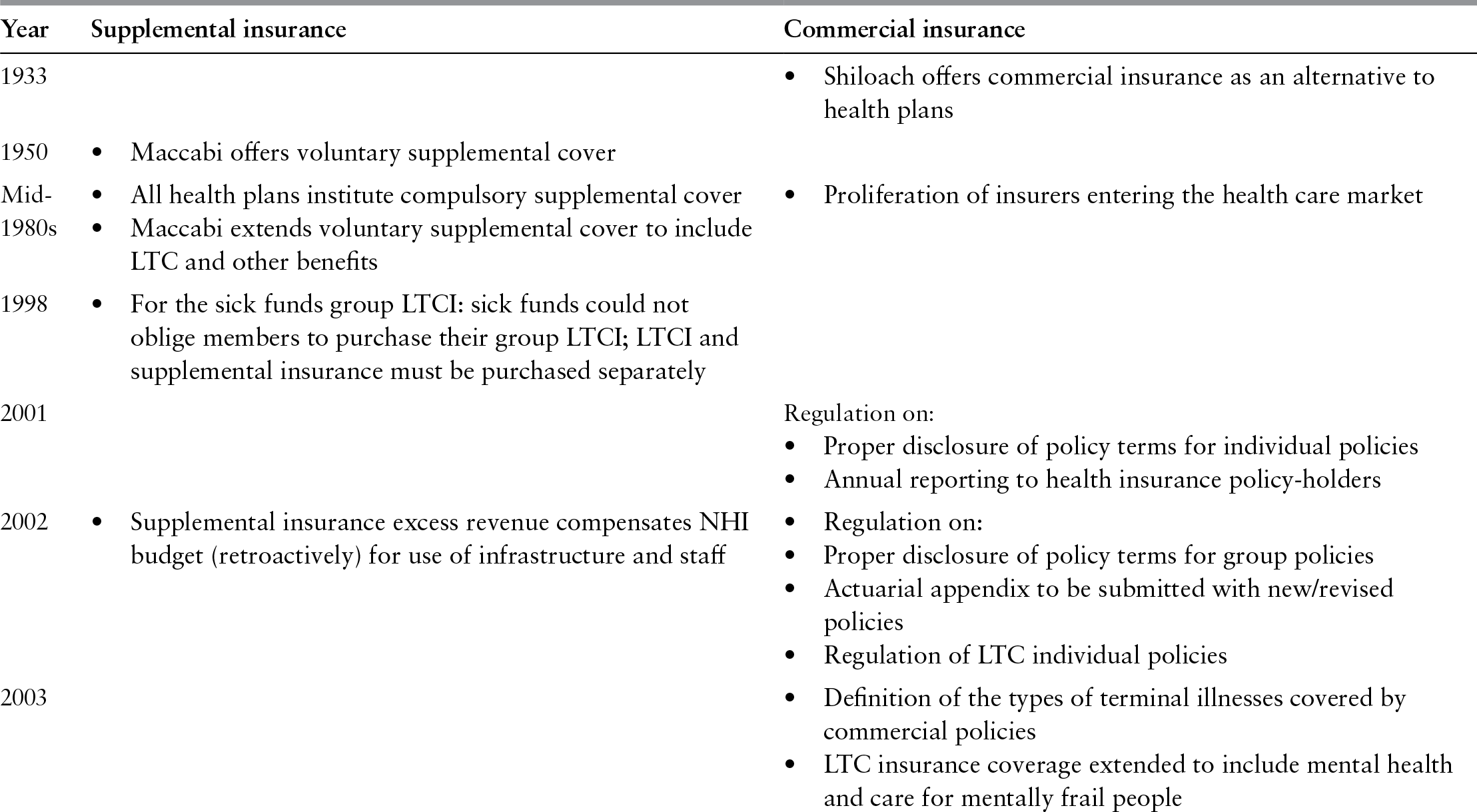

Table 8.4 Development of supplemental and commercial insurance markets in Israel, 1933–2017

| Year | Supplemental insurance | Commercial insurance |

|---|---|---|

| 1933 |

| |

| 1950 |

| |

| Mid- 1980s |

|

|

| 1998 |

| |

| 2001 |

Regulation on:

| |

| 2002 |

|

|

| 2003 |

| |

| 2004 |

| |

| 2005 |

|

|

| 2007 |

|

|

| 2010 |

| |

| 2015–2017 |

|

|

Note: CI, commercial insurance; HP, health plan; LTCI, long-term care insurance; NHI, national health insurance; SI, supplementary insurance.

Dual coverage and attempts to reduce this phenomenon

A major consequence of the private health insurance market complexity and inability of consumers to wisely choose coverage is the dual coverage phenomenon (see Table 8.3).

Besides the lack of information regarding private health insurance coverage and how to claim it, the insureds also face administrative barriers, such as the requirement to obtain pre-approval before accessing care and a time lag between payment for treatment and reimbursement. SI will only reimburse policy-holders for listed operations, medical implants and medications provided by listed providers selected by the HP. In practice, it is not easy to obtain lists of services and providers. Some are available at HP clinics, but members may not know this. Also, in spite of regulations for proper disclosure, supplemental and commercial policies may not be accessible to a lay person due to the use of legal jargon and unfamiliar concepts and the overwhelming amount of detail they contain. There is a large diversity in private health insurance products, with complex policies and a wide range of services offered. The policies vary in their contents and prices, and some insurance companies used to market different services (that is, coverage for medications/ surgeries/ severe diseases) as one bundled package, instead of allowing the purchase of separate coverage for each type of service. As a result, consumers may not have been able to compare among insurers and products, choose the most suitable coverage or take the full advantage of their benefit entitlements (Reference 298Brammli-Greenberg, Gross and MatzliachBrammli-Greenberg, Gross & Matzliach, 2007; Reference Brammli-GreenbergBrammli-Greenberg et al., 2014).

To keep up with the growth in the supplemental and commercial markets and with the growing competition between them, and to protect consumers from problems caused by double cover, the Insurance Commissioner intensified its regulation of commercial health policies. New regulations required proper disclosure of policy terms in individual (Ministry of Finance, 2001a) and collective (Ministry of Finance 2002a, 2005a) policies, which were to be set out in concise, user-friendly forms, using lay terms; annual reporting to policy-holders (Ministry of Finance, 2001b); an actuarial appendix to be submitted with new or revised policies (Ministry of Finance, 2002b); definition of the types of terminal illnesses covered (Ministry of Finance, 2003a); minimum standards for major medical procedures (Ministry of Finance, 2004a); regulations for approving premium increases (Ministry of Finance, 2005b); and the appointment of an actuary for health policies (Ministry of Finance, 2005c; Reference Brammli-Greenberg, Gross, Bin Nun and OferBrammli-Greenberg & Gross, 2006).

Recent regulation further attempted to tackle CI complexity and dual coverage. In 2015 the Ministry of Finance approved several changes aiming to improve transparency regarding coverage and prices, improve simplicity of insurance products so as to ease consumer choice of policy, thus enhancing competition among commercial insurers. Among others, the Ministry of Finance created a standard policy for health expenses, with set coverage of services (surgeries and specialist consultations), co-payments and premiums.

In order to tackle the lack of information on the part of consumers, in 2014 the Ministry of Health introduced a website that gives access to transparent information about the coverage of the NHI and private health insurance benefits packages. The idea is to empower insured individuals with knowledge and awareness of their rights and eligibility to benefits, so they can demand them from the HPs and/or private insurers; and if refused, they can refer the case to the supervisor (the Ministry of Health). This policy instrument addresses market failures related to information asymmetry and can potentially improve competition among the HPs and within the private health insurance market (Reference Brammli-GreenbergBrammli-Greenberg et al., 2014). The driving forces behind it were growth in the market and increased media exposure of evidence of information asymmetry and consumer confusion over the differences between CI and SI. It was also part of a broader effort by the Ministry of Finance to regulate the insurance and capital markets (Reference AntebiAntebi, 2005, Reference Antebi2006, Reference Antebi2007 oral presentations).

Another reason for the high level of double coverage in Israel was the fact that until 2014 the CI fully reimbursed the insured for surgeries from the first shekel, even if they were already paid for by the NHI or the SI. This means that the insured earned the cost of the surgery akin to a cash benefit.

In 2007, the Insurance Commissioner obliged insurers to offer new policies for private surgery that cover only those expenses that are not covered by supplemental plans (that is, supplementary to SI cover) (Ministry of Finance, 2007b). This was intended to safeguard consumers’ rights by preventing them from purchasing an expensive CI policy, which is difficult to claim, and preventing insureds from undergoing (unnecessary) surgeries based on economic considerations. Despite the greater economic viability of this type of policy, only 13% of the insured with individual CI and 18% of the insured with collective CI have such a policy.

In 2014 the Insurance Commissioner prohibited CI from reimbursing the insured for surgeries covered by the NHI or by the SI. This change is expected to lower dual coverage but it is too early to see its effects in the uptake of private health insurance.

Impact of the private health insurance market on national health spending

During the last decade, Israel has seen a steady growth in national spending on health in per capita terms. In 2005, national per person spending on health increased from US$1769 in 2005 to US$2822 in 2016 (current PPP prices). The main driver of that increase was the growth in private spending on health, which rose from US$672 per capita in 2005 to US$1120 in 2016 (OECD, 2017).

Private health insurance (supplemental and commercial) accounted for a significant share of the increase in private health spending. Both the price of private health insurance premiums and the number of insureds have increased significantly in recent decades. Premium receipts for SI increased by almost 200% between 2007 and 2014 (from NIS2.1 billion to NIS4.1 billion) and total income from payments for CI premiums for illness and hospitalization policies increased from NIS2.1 billion in 2003 to NIS5 billion in 2014 (a total increase of 240%) (Ministry of Health, 2014d; Ministry of Finance, 2015a).

Private health insurance is one of the main sources of funding for private health care providers, who contribute to the increase in demand for more private health care and consequently to the increase in private spending (Ministry of Health, 2014d). In recent years, policy-makers have been concerned with possible spill-over effects over the public health system derived from the sharp increase in private spending. In 2014 the Ministry of Health appointed an Advisory Committee to Strengthen the Public Health Care System, which gathered evidence regarding the exogenous negative effects of the private health insurance on the public health system and recommended diverse policy changes attempting to strengthen the public system (Ministry of Health, 2014d). Some of these recommendations were implemented in the 2015 reform, including efforts to improve information and transparency and reduce the dual coverage phenomenon (see above and also Reference Brammli-GreenbergBrammli-Greenberg et al., 2014).

It is also claimed that private health insurance promotes the policy goal of curbing government spending on health, thereby averting the need to raise taxes to cover the NHI budget. There are three arguments here. First, private health insurance reduces pressure on the government to increase the NHI budget because it provides people with access to benefits not covered by the NHI. Second, it provides access to private providers, apparently reducing the public workload and helping HPs to stay within their NHI budget. Third, the 2005 Ministry of Health rules oblige HPs to transfer profits from SI to cover deficits in their NHI budget, theoretically mandating private resources to fund the NHI. For example, in 2015 the HPs received NIS4.3 million from SI surpluses, which represented 8.7% of their total revenuesFootnote 21 (Ministry of Health, 2016).

However, evidence shows that private health insurance not only does not reduce public spending on health, but actually increases it. For example, because of cream-skimming by the private sector, public sector treats the most severe and complicated cases, including re-admissions and complications from surgeries performed in the private sector (Reference Tuohy, Colleen and StabileTuohy, Colleen & Stabile, 2004; Reference PaolucciPaolucci, 2012). Another adverse exogenous effect of the growing private sector (funded mainly by private health insurance) is the brain drain from the public to private sector. Most physicians in Israel practice in both sectors. Physicians in the private sector are paid more so they have strong incentives to reduce their public sector hours. Indeed, it seems that many senior physicians have reduced their public sector activity in favour of private practice, which has led to increasing waiting times in the public sector (Ministry of Health, 2014d). Finally, private health insurance and other types of private funding are a regressive way of funding health care, which entails problems of access to care among vulnerable populations.

Discussion and conclusion

National health insurance is the main tool for achieving most health-financing policy goals, including universal financial protection, equity in financing, equity of access to health care, incentives for quality and efficiency in care delivery and administrative efficiency. Supplemental and commercial private health insurance contribute to achieving some of these goals, but compromise others (Reference Zwanziger and Brammli-GreenbergZwanziger & Brammli-Greenberg, 2011).

Private health insurance contributes partially to financial protection by enhancing access to services, including a range of catastrophic and routine items. This in particular applies to SI, which is open to every resident for relatively inexpensive premiums (priced between €1.5 per month for a basic plan for members aged 0–17 years to €43 per month for an extended plan for people aged over 80 years). However, both supplemental and commercial cover undermine vertical equity because premiums are not income related and cover is lower among the most vulnerable population groups such as those with low incomes, Arabs and elderly. CI further compromises access by excluding policy-holders from benefits related to pre-existing conditions. They also lower horizontal equity by creating a two-tiered system of access to health care. For example, private health insurance owners wait less time to receive care, and have more choice of providers.

Reasons for expansion of the private health insurance market

Historical and political factors have played a prominent role in shaping the structure of the Israeli private health insurance market, in which private health insurance is offered both by commercial insurers and the non-profit HPs. When they were established, HPs could define their own benefits and premiums. In the 1980s they offered compulsory supplemental cover to increase revenue and improve quality, and two of them also offered voluntary supplemental cover. Following political pressure from those two HPs, the 1995 NHI reform allowed them to continue offering voluntary benefits, and the other two HPs subsequently introduced voluntary cover. Thus, the government adopted a structure integrating private and public insurance, in spite of the problems associated with the provision of both types of insurance by the same entity (Reference Gross and Brammli-GreenbergGross & Brammli-Greenberg, 2004).

Subsequent regulations reflect the policy importance placed on equality as well as political interest in responding to public opinion. The new rules introduced in 1998 were aimed at redesigning SI as a social insurance plan by prohibiting risk selection, defining premiums in a way that would make the healthy subsidize the ill, and by authorizing the Ministry of Health to regulate all future changes in policies and premiums. The strict regulation of SI is particularly striking in comparison to the loose regulation of other aspects of HPs’ conduct, such as quality of careFootnote 22 (Reference Gross and HarrisonGross & Harrison, 2001), and can be attributed to political desire to minimize the inequality resulting from supplemental cover.

Analysis of the growth of the CI market since 1995 underscores the role of market forces as well as the interests and power of the insurance companies. The expansion of the supplemental market raised consumer awareness of private health insurance and motivated commercial insurers to increase activity in this area, which enjoys relatively high profits. To gain a competitive edge, commercial insurers market their cover as a third layer on top of NHI and supplemental benefits (which they present as inexpensive and nonprestigious health insurance)Footnote 23, thus encouraging double cover. In addition, commercial insurers’ strong position in the Israeli capital markets and, consequently, in the economy, has enabled them to lobby for exclusive rights to cover two major risks not covered by NHI (LTC and life-saving/extending medications), leading to regulations that safeguard and may even increase commercial market share. Here, the support of the powerful Budget Division of the Ministry of Finance undoubtedly influenced the policy outcome (Reference Gross and Brammli-GreenbergGross & Brammli-Greenberg, 2007). However, as commercial market share has grown, regulatory intervention has intensified, mainly to protect consumers.

Cultural factors have also contributed to the growth of the private health insurance market. These include declining confidence in the scope and quality of public services and the growing importance of free choice of provider. The growing importance of choice appears to have replaced the pre-state, pioneering value of equality, not only in health care, but also in other public services, such as education and civilian security. This change is reflected in growing income inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient, which rose from 0.233 in 1950, to 0.376 in 2012. In a population survey conducted in 2014, 37% of respondents reported being confident that they would receive the best and most effective treatment within the NHI for a serious illness and 29% were confident that they would be able to afford treatment for a serious illness. These figures are low compared with high-income countries (see Fig. 8.5) and had declined compared with 2012 (Reference Brammli-Greenberg and Medina-ArtomBrammli-Greenberg & Medina-Artom, 2015). The declining confidence of the Israeli population in the public health system is also related to the declining share of public funding, which places Israel among the countries with the lowest share of public funds in total spending on health (60% compared with an average of 72% among OECD countries).

Figure 8.5 Public expenditure on health and confidence in the health system in Israel and selected OECD countries, 2012

The interaction between the private health insurance and the NHI system

The debate on the inclusion of life-saving medications in private health insurance cover highlights the close interaction between SI and the NHI system. Since the introduction of NHI, the supplemental market has been shaped by a combination of competitive forces and government intervention.Footnote 24 The latter has significantly altered the features of SI and the size and characteristics of the population it covers. This, in turn, has had indirect effects on the CI market.

The interactions between public and private cover are complex and the effects of these interactions are not always easy to establish. Private health insurance may distort incentives and resource allocation in the wider health system in different ways. For example, it covers benefits that people are willing to pay for but that are not necessarily cost-effective, which may not be the best use of the resources from a health system perspective. However, some cost-effective services – such as Herceptin for breast cancer and drug-coated stents – that were originally only provided in supplemental plans, have subsequently been added to the NHI benefits package. Yet, it is not clear whether private health insurance may serve as a tool to create public pressure to expand the publicly financed benefits package, or alternatively, it allows the government to exempt itself from the responsibility and duty of including certain services in the health basket once they are provided by private health insurance.

This interaction and the concerns that it creates have been vigorously debated in public and policy circles. Initially, there were pressures to curb the growth of private health insurance by forbidding HPs from offering supplemental plans. Today, in view of its market size, the possibility of doing so is less realistic and SI is accepted as an integral part of the health system. CI is also encouraged and given exclusive rights to cover services excluded from NHI, such as long-term care. The Advisory Committee to Strengthen the Public Health Care System has suggested that the close relationship between the private health insurance market and the NHI system is one of the reasons for the expansion of the former (Ministry of Health, 2014d). Nevertheless, the government is aware of the undesirable effects of private health insurance and therefore makes increasing use of regulatory tools to safeguard consumer interests and protect the public health system.

Future directions for the market and public policy towards it

Although many regard SI as compromising important social values, an issue that is frequently debated, the system endures. The HPs have exerted pressure to allow them to continue to cover private services, which are valued by their members and strengthen their competitive position in relation to commercial insurers, who also cover private services. Physicians and for-profit hospitals also benefit from the ensuing proliferation of private services, since it provides them with an opportunity to earn extra income. However, given that access to supplemental benefits is lower among the vulnerable population, and that SI has some adverse effects on the public system, the latest regulations attempted to improve the supplemental model to maximize its advantages and overcome its disadvantages, and also to limit the growth of private health insurance, particularly to curb dual coverage.

Observed trends suggest that growth in the supplemental market has reached a ceiling. However, although total coverage rates have stabilized, take-up is still relatively low among lower socioeconomic groups and minorities (the Arab population and immigrants from the former Soviet Union), so there might be potential for market growth, especially in the SI segment, which has lower premiums and is considered part of the public system. Other potential market growth is the creation of new layers of SI plans. Simultaneously, the CI may also create new health insurance products, although the coverage rate is already high compared with other countries.

Analysis of commercial insurers’ strategies shows that they are innovative and active in seeking opportunities to expand coverage to niches not covered by SI or to exploit weaknesses of the NHI. The CI market may therefore grow in future if commercial insurers succeed in preventing major changes to the SI, as they have done in the past, or if they manage to take further advantage of limits to public coverage and quality. Yet, this might be mitigated if the 2015–2017 reform succeeds in attaining its goal of limiting dual coverage.

Other factors that may strengthen the private health insurance market include population ageing and growth of chronic comorbidities (implying increased health care need and use), accelerated technological advances, and reductions in government spending leading to lower public spending on health care and greater privatization of care delivery. All this is accompanied by the growing trend of distrust of the population in the public system (Ministry of Health, 2014d).

In Israel, as in other countries, private health insurance is seen by policy-makers as a second-best option that enables the government to respond to public expectations for expanded health coverage without increasing public spending on health. However, the market’s effects are ambiguous. The alternative to reconciling the two insurance markets (public and private) without negative spillover effects on the public sector is to strengthen the NHI and make it more competitive towards private health insurance.