Chapter 1 Making space

I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space while someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged.1

To begin with the word: theatre, from the Greek theatron (θέατρον), means ‘the seeing place’ and ‘at the very basis of the phenomenon of theatre as it is found in a wide variety of cultures is the assumption of a particular spatial configuration suggested by the word theatre itself – a place where one sees’.2 David Wiles puts it succinctly when he writes: ‘Theatre is pre-eminently a spatial medium, for it can dispense with language on occasion but never with space.’3 However, Henri Lefebvre begins The Production of Space with a warning: ‘Not so many years ago the word “space” had a strictly geometrical meaning: the idea it evoked was simply that of an empty area.’4 The commonsense notion that space was simply an ‘empty area’ – the notion that Lefebvre challenged – has begun to have a particular resonance for theorists of theatre, in that it echoes Peter Brook’s influential definition. Since its publication in 1968, Brook’s opening to The Empty Space has often been taken to encapsulate the fundamental essentials of dramatic performance. However, as spatial theory has developed over the subsequent decades in the work of figures such as Lefebvre, Yi-Fu Tuan, Edward Soja, Doreen Massey, and others, the concept of an empty space has become increasingly untenable. ‘Theatre only “in all innocence” can occur in an empty space,’ as Alan Read puts it.5

Between the recognition that theatre is fundamentally a spatial form, and the parallel recognition that space can no longer be treated as an empty receptacle, it is time to begin thinking spatially about Irish theatre. In the early 1990s, Read could still observe that ‘the theatre image’s presence in time and space has, until recent work, been neglected’.6 If that balance has been redressed elsewhere, in an Irish theatre in which the playwright continues to be the dominant artist, analysis – and the theorisation of that analysis – still finds it difficult to go beyond the word. From the outset, this raises a problem. ‘Any search for space in literary texts will find it everywhere and in every guise,’ cautions Lefebvre, ‘enclosed, described, projected, dreamt of, speculated about’.7 He goes on to argue that in beginning to think spatially, we run the danger of confusing very different forms of space, and hence he insists that we need to disentangle and demystify space by distinguishing among three basic concepts: space as physical, space as mental (including logical and formal abstractions), and space as social.8 For Lefebvre, the distinction among these three categories is not in their form, or in their ontological status, but in their mode of production, a point that he states as a foundational principle: ‘(Social) space is a (social) product.’9

Lefebvre goes on to define three understandings of space – sometimes referred to as his ‘spatial triad’ – that can form the basis for a theory of theatre space. The first element is ‘spatial practice’, which is sometimes glossed as ‘perceived’ space, the commonsensical, ‘everyday’ space in which we live, and in which social life exists. This can be distinguished from ‘representations of space’, ‘which are tied to the relations of production and to the “order” which those relations impose, and hence to knowledge, to signs, to codes’. Also sometimes called ‘conceived’ space, this is the space of planners, of cartographers, and, to some extent, of theorists of space themselves. However, Lefebvre complicates what could be a fairly straightforward binary opposition of spatial relations – the perceived as opposed to the conceived – by differentiating these two categories from what he calls ‘representational space’, which he later refers to as ‘lived’ space, but which is ultimately more complex than either term suggests.10 For Lefebvre, ‘lived space’ ‘embodies complex symbolisms, sometimes coded, sometimes not, linked to the clandestine or underground side of social life, and also to art (which may come eventually to be defined less as a code of space than as a code of representational spaces)’.11

Lefebvre’s influence on a later generation of social and cultural theorists has contributed to a ‘profoundly spatialised historial materialism’,12 alert to the view that space is never simply ‘there’, never truly empty, but is produced through human agency. However, his influence on the theorisation of theatre has had less impact than, for instance, Judith Butler’s work on performativity, or other theorisations of the body. Lefebvre has informed David Wiles’s historical work on performance spaces,13 is cited by Gay McAuley in her Space in Performance (2000),14 and is a key influence on Alan Read’s Theatre and Everyday Life (1993), the title of which signals the impact of Lefebvre’s theorisation of ‘the everyday’. However, Lefebvre’s own comments on theatre are fleeting, if suggestive: ‘Theatrical space certainly implies a representation of space – scenic space – corresponding to a particular conception of space (that of the classical drama, say – or the Elizabethan, or the Italian). The representational space, mediated yet directly experienced, which infuses the work and the moment, is established as such through the dramatic action itself.’15

In these few sentences, we get a sense of the potential complexity that Lefebvre’s model brings to the theatrical event, and of its place within other spatial configurations, rippling outwards from the theatre building, to the city, to the national space, and beyond to a wider world. Lefebvre’s is not a structuralism that offers the sterile pleasure of nomenclature, of naming inert objects. Instead, his is a dynamic theoretical model, in which the three modes of producing space – the perceived, the conceived and the lived – interact, moment by moment. This makes it profoundly theatrical. For Lefebvre, space is produced not in the past tense but in the present continuous, just as happens in theatre. What is more, the production of lived space is participative, a process that involves not only performers, but also the audience. An audience, as Herbert Blau puts it, ‘is not so much a mere congregation of people as a body of thought and desire. It does not exist before the play but is initiated or precipitated by it; it is not an entity to begin with but a consciousness constructed.’16

The constitutive presence of an audience in the auditorium makes it possible to see the production of space in the theatre as a subset of the wider social production of space. However, there is at least one major difference between the production of space in the theatre and that which occurs in the wider society: in the theatre, there are strict spatial boundaries, defined according to explicit criteria; within those boundaries, a space is produced, but it only endures for the clearly defined duration of the performance. One consequence of this is that spatial production in the theatre must take place at an accelerated pace, with an intensity and focus that usually exceeds the rhythms of spatial production in the everyday world. As a result, theatrical performances are, as Bruce A. McConachie puts it (borrowing a term from Joseph Roach), ‘condensational events’,17 a concept that recognises the two-way flow from performance to the world outside, while at the same time acknowledging the intensity that is one of the definitional qualities of performance (and, as we will argue in Chapter 4, constitutes one of its attractions). In Ireland, however, this condensational quality is not always confined to the stage, but is shared by key moments in Irish history, particularly the 1798 Rising, Robert Emmet’s 1803 rebellion (of which there were at least ten stage versions between 1853 and 1905) and the Easter Rising of 1916. ‘When the Easter Rising began,’ observes James Moran, ‘some bystanders believed they were witnessing the opening of a play.’18 Hence, the concentrated, intensified production of space in performance is reliant upon spaces produced outside of the theatre; however, in a particular society or historical moment, those socially produced spaces may have already been the subject of intense, non-theatrical condensational spatial production, which alerts us to the difficulties of always tracing spatial boundaries of the theatrical precisely. To put it simply, a space may already appear theatricalised before it appears on stage.

The very existence of a designated ‘theatre’ (whether in the sense of a building, an institution, or a temporary site) is the product of a culturally specific set of spatial understandings. At the same time, once a space for theatrical production has been constructed, the real physical limitations of that space will have a formative effect on what takes place there. An extreme example can help to make this case: in 2007, the Performance Corporation, an Irish company specialising in site-specific work, staged a play, Lizzy Lavelle and the Vanishing of Emlyclough, in a sand dune on the Mayo coast. The nature of the performance space – the shifting movement of the sand, the cauldron shape created by the dune, the metaphorical connotations of sand – all played a constitutive role in the resulting performance, physically and conceptually. At the same time, audiences watching the play brought to the venue a set of expectations concerning the nature of theatrical space, which they were able to apply to a sand dune, a space in other respects utterly dissimilar to a conventional theatre building. The kind of interaction between the perceived space (the sand dune), the conceived (theatrical space), and the lived (the experience of taking part in a performance) may not be as obvious or as explicit as in a conventional proscenium arch theatre: but it happens in all theatre nonetheless. Indeed, the complexity and interpenetration of these various productive forces have been the focus of a small, but growing body of work, notably that of Herbert Blau and Marvin Carlson: ‘The way an audience experiences and interprets a play, we now recognise, is by no means governed solely by what happens on the stage. The entire theatre, its audience arrangements, its other public spaces, its physical appearance, even its location within a city, are all important elements of the process by which an audience makes meaning of its experience.’19 For the past century or so, it has generally been assumed that one of the conceptions of space that Irish audiences bring with them into the site of theatre (along with the concept of theatre space itself), has been the space of the nation. ‘The starting point here is the assumption’, argues Christopher Murray in his Twentieth-Century Irish Drama: Mirror Up to Nation, ‘that in the Irish historical experience, drama . . . and theatre . . . were both instrumental in defining and sustaining national consciousness’ – to which it might be added that the reverse was also generally assumed to be true.20 Again, as with the idea that there might be such a thing as an empty space, the idea of the national theatre has been subject to a critical debate, characterised by the idea that such a thing should not, in theory, exist – even if it clearly does. For Loren Kruger, ‘the idea of representing the nation in the theatre, of summoning a representative audience that will in turn recognize itself as a nation on stage, offers a compelling if ambiguous image of national unity, less as an indisputable fact than as an object of speculation’.21 If the idea of a national theatre constitutes a ‘conceived space’ saturating every pore of the national territory, the locations of ‘perceived’ sites of performance are not so evenly distributed. Theatre buildings are generally solid, substantial structures, which require concentrated populations, roads, public transport and legislation – in short, all of the apparatus of a functioning state, which is rarely constant through time, or distributed evenly throughout the national space. Thus, whether considered diachronically or synchronically, the parallel maps of the conceived and perceived spaces of a ‘national’ theatre will always have points at which they do not match.

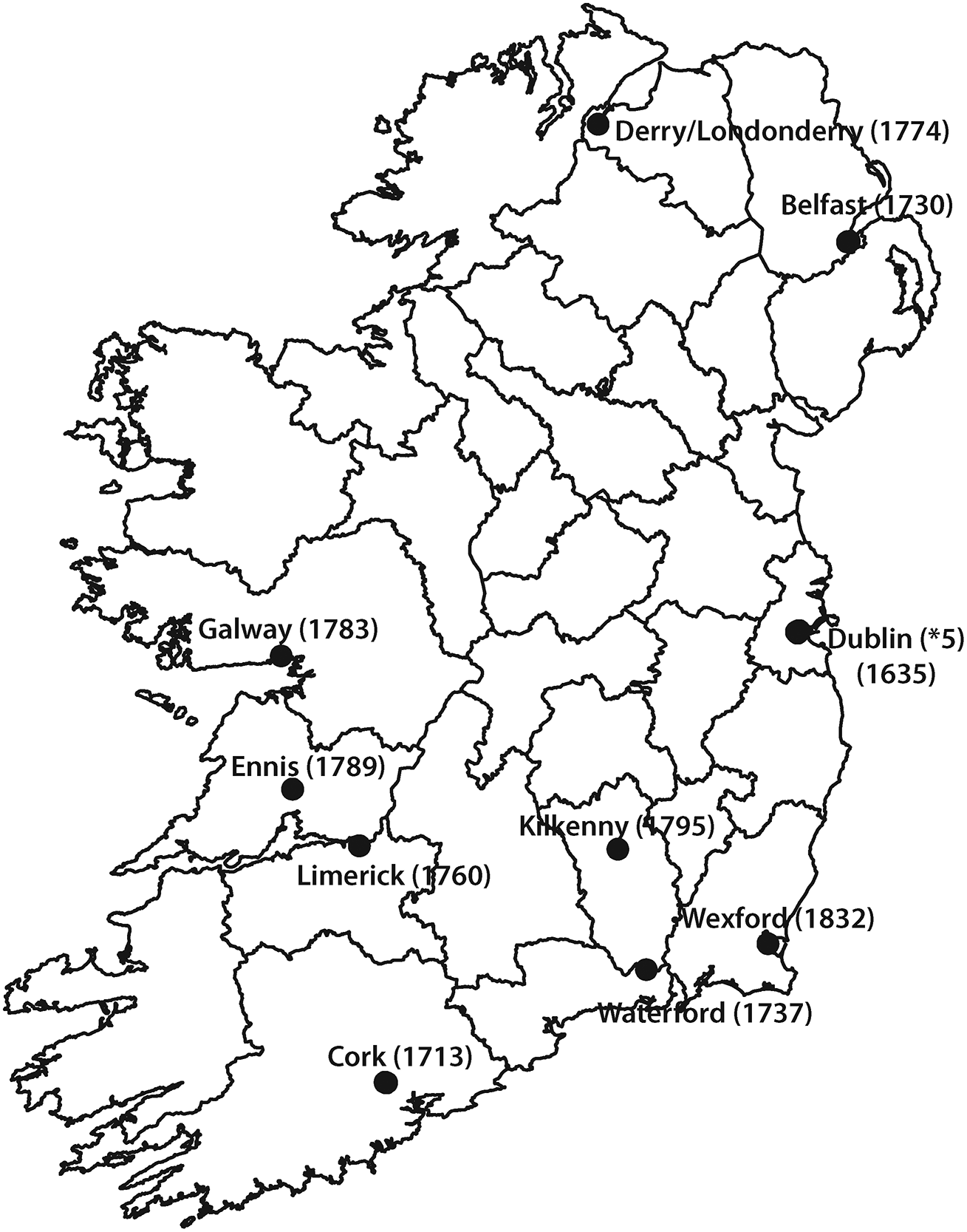

This is particularly true of Irish theatre. Like most theatre histories, the history of Irish performance spaces is discontinuous, marked by shifts and changes over time, which nonetheless leave their traces. Possibly because theatre requires a relatively stable urban society, the first Irish theatre building cannot be dated earlier than 1635,22 relatively late for a Western European country. That first theatre was an indoor Caroline platform stage in a building on Werburgh Street, just beside the colonial administrative centre of Dublin Castle, to which it was closely bound with ties of patronage. The Werburgh Street theatre lasted only a few short years, closing as a result of the political tensions leading up to the War of the Three Kingdoms in 1640. Following the Restoration, the first proscenium arch theatre in Ireland (and one of the first in the British Isles) opened in Smock Alley in 1662. Once again, located in what is now the western end of the Temple Bar district, this theatre was in what was then the nexus of power: Dublin Castle was only a few hundred yards to the south, the shadow of Christchurch Cathedral fell from the west, Trinity College, Dublin was a short distance to the east, and the Courts were visible just across the River Liffey. If maps of Ireland from the time marked the area surrounding Dublin as ‘The Pale’, defined by the reach of a centralised state, Smock Alley Theatre was at its geographical epicentre. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, that situation began to change, both as control of the state extended outwards, and as the theatre became less explicitly dependent on the patronage of Dublin Castle. By the 1730s, Smock Alley (along with a rival theatre in Aungier Street) began to tour to other urban centres in the summer season, principally to Belfast, Limerick, Cork, Kilkenny and Waterford. As theatre cultures developed outside of Dublin, this in turn led to theatre building in other Irish cities in the second half of the eighteenth century. By the time visiting touring companies came to dominate Irish theatre in the 1820s, there was thus a network of Irish theatres already in place. At this point, the shape of the Irish theatrical map changed, from an area defined by its centre (Dublin), to a network of points connected to the centre, and to the ports from which companies travelled back and forth to England. As with any map, there were blank spaces. Galway, in spite of being a centre of population for the western seaboard, rarely saw theatre in the eighteenth century; as a result, it had no substantial theatre building, and was thus bypassed by the major touring companies of the nineteenth century. Londonderry joined the Irish theatre world relatively early in 1741, and was included in tours throughout the second half of the eighteenth century. However, as it was increasingly left out of transportation networks over the course of the following century, so fewer and fewer plays were staged there, until it too was effectively off the map of Irish theatre.

The establishment of the Irish Literary Theatre by Yeats, Lady Gregory and Edward Martyn in 1897 initially seemed like an attempt, in spatial terms, to re-draw the Irish theatre map (Map 1). From 1903 onwards, after the dissolution of the original organisation and the subsequent creation of the significantly named Irish National Theatre Society, the company began to tour, initially to London, but soon travelling throughout Ireland, to England, Scotland, and, after 1911, the United States. Not long after it assumed the title of ‘National Theatre’, Yeats asked: ‘What is a National Theatre? A man may write a book of lyrics if he have but a friend or two that will care for them, but he cannot write a good play if there are not audiences to listen to it.’23 As Loren Kruger would ask of the imagined national audience: are they ‘spectator or participant? Incoherent crowd or mature nation?’24 In 1903, as the company set out for London, it was not clear whether a national theatre found its audience dispersed throughout the nation (which, in the case of post-Famine Ireland, could be extended to include its diaspora), or whether a national theatre could find a ‘representative’ audience in its capital; or, indeed, whether newspaper reports in Ireland of an Irish company playing in New York were enough to make that company part of the national imaginary. The question may have been conceptual, but it also had a concrete spatial dimension: it was another way of asking if in order to be ‘national’, a theatre had to tour nationally, or if it could remain based in the capital, with occasional forays overseas.

Map 1 Dates on which theatres first opened in Irish towns and cities, 1635–1832. The gradual and irregular spread of theatre culture outwards from Dublin in the eighteenth century can be traced in the pattern of theatre building. This period established the basic patterns of Irish theatre geography that persisted into the nineteenth century.

Nor was the title of ‘national theatre’ uncontested in those years. Apart from various groups who broke away from, or who competed with, what after 1905 became the company directed by Yeats, Lady Gregory and Synge, there was the question of Ulster, and the claim of Dublin to be the centre of Irish space. Tellingly, the Ulster Literary Theatre published a manifesto in the first issue of its journal Uladhin 1904, which contrasted the new venture in Belfast with ‘the stage of the Irish National Theatre in Dublin . . . where a fairly defined local school has been inaugurated’,25 thereby steadfastly refusing to recognise the Dublin theatre as anything other than another ‘local’ theatre. Although the Irish National Theatre Society Limited continued to tour, its spatial identity was effectively settled in 1904 when it moved to the site of its current home, on Dublin’s Middle Abbey Street, and came to be known by the name of the street on which it was situated: the Abbey Theatre. This gave the ‘national theatre’ a physically defined spatial identity. Physical space would be given institutional recognition after August 1925, when the company was given a state subsidy as the ‘national theatre’, giving substance to the assurance given to Lady Gregory, as early as January 1922, that the new Irish Free State government viewed the Abbey as ‘the “National Theatre” of Ireland’.26

Overlaying this centred map of Irish theatre history there is another, shifting map of Irish theatre geography, and a parallel theatre geography can be traced as hundreds of amateur theatres grew up around the island from the late 1920s onwards. Over time, the amateur movement organised itself into regional structures of competitive theatre festivals located in centres such as Tubbercurry and Killarney. In 1953, these regional competitions came together to create the national All-Ireland Theatre Festival. Significantly, this national theatre structure, which arose from the combination of individual regional theatre cultures, chose as its centre not the administrative capital of the state, Dublin, but the geographical centre of the island: Athlone. Hence, for much of the twentieth century, the lived experience of theatre for a great many Irish men and women outside of Dublin was of their local amateur theatre company, supplemented by a number of small touring companies (most notably that of Anew McMaster), who travelled regular circuits, often using the same venues as the amateur companies.

This dispersed geography first began to merge with the map of the state-sanctioned ‘national theatre’ in 1974, when the Irish Theatre Company was created as one of only three theatre companies to receive significant government funding in the Irish Republic (the other two were the Abbey and the Gate; the Lyric Theatre was the prime recipient of state subsidy in Northern Ireland). The following year, Druid Theatre Company was formed in Galway, and it soon took on touring to smaller towns as part of its remit. Field Day Theatre Company (formed in 1979) was even clearer in its understanding of the relationship between touring and functioning as a national theatre. While from the premiere of their first production, Translationsin 1980, Field Day were associated with Derry, their clear intention was not to be tied to any one location. ‘We toured Ireland, North and South, East and West’, co-founder Stephen Rea later told an interviewer, ‘and we started to have an agenda, which was to probe the condition that the country was in and to ask questions about it. We were sometimes attacked for being narrowly nationalist, but we were far from that.’27

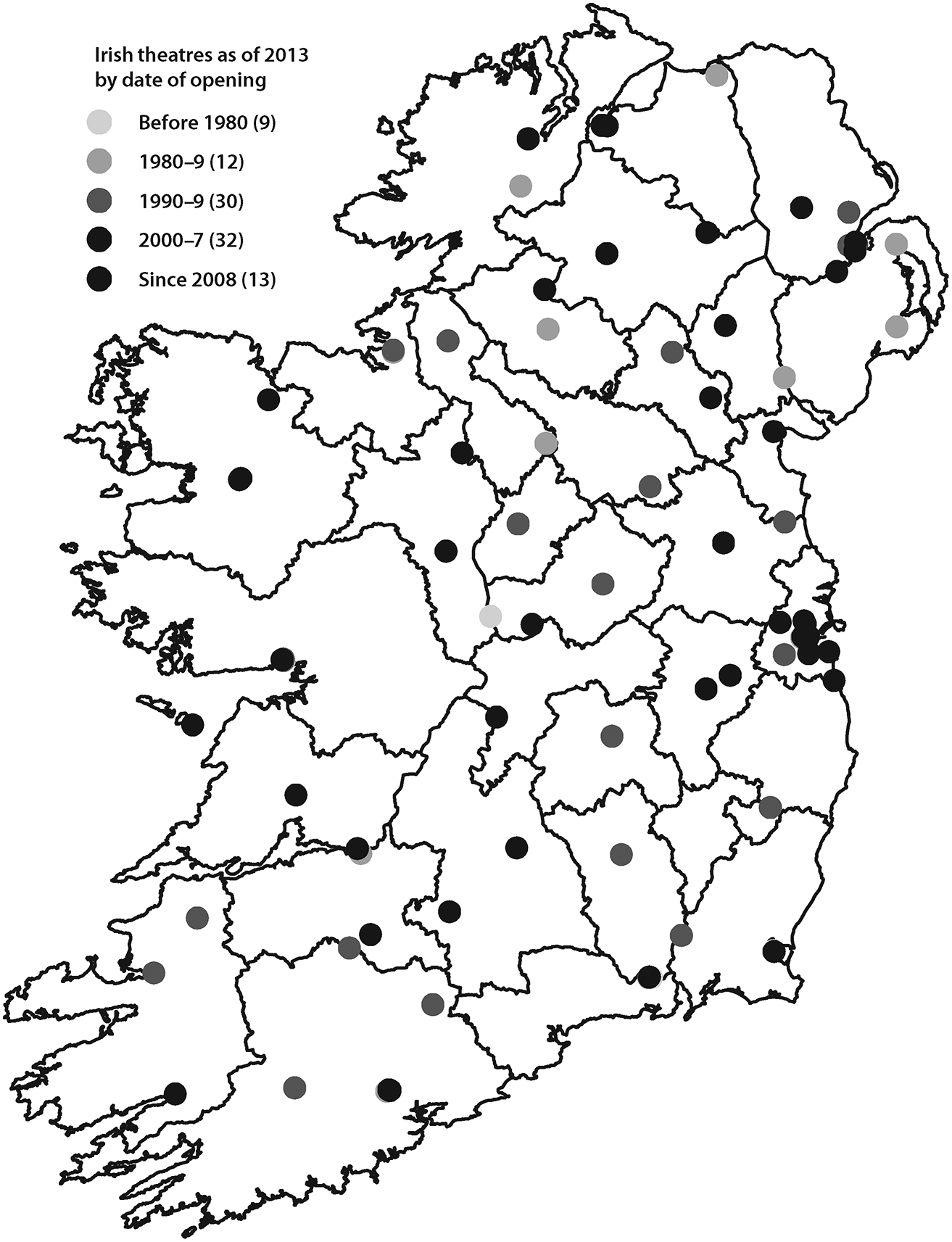

In retrospect, the burst of touring activity between 1974 and the mid 1980s now seems like the prelude to a period in which a dispersed Irish national theatre made the transition from the conceived to the perceived. Shortly after the early Druid and Field Day tours, arts funding bodies both in the Republic of Ireland and in Northern Ireland began to support the construction of regional theatre buildings (usually with the cooperation of local amateur or semi-professional theatre groups). There also was new support for professional theatre companies beyond the three main Dublin- and Belfast-based theatres (the Abbey, the Gate and the Lyric). In the greater Dublin area, a suburban necklace of theatres eventually circled the city: the Helix in Glasnevin; axis in Ballymun; Draíocht in Blanchardstown; the Civic Theatre in Tallaght; the Mill Theatre, Dundrum; and the Pavilion in Dun Laoghaire. Meanwhile, further outside of Dublin, theatres such as the Solstice Arts Centre in Navan, the Riverbank in Newbridge, the Hawk’s Well in Sligo, the Town Hall in Galway and the Ardowen Theatre in Enniskillen would create a theatre geography that was increasingly dispersed, if not decentred. By the first decade of the twenty-first century, the bulk of state funding would continue to be directed to the Abbey in the Irish Republic, and to the Lyric Theatre in Belfast, but the map of Irish theatre now had dots all over it (Map 2).

Map 2 A contemporary geography of Irish theatre: the locations of theatre venues in Ireland as of 2013 by date of opening, showing the shift in theatrical geography since 1980; only 9 venues pre-date 1980; 12 date from 1980–9; 30 from 1990–9; 32 from 2000–7; and 13 have been built since the beginning of the economic crisis in 2008.

If the idea of a national theatre constitutes, in Lefebvre’s terms, a conceived space, and the infrastructure of theatre sites constitutes its perceived space, attempts to align them have produced at least two paradoxical effects. First, as regional theatres have come into being around Ireland – from the Ulster Literary Theatre in Belfast in the first decade of the twentieth century, to more recent theatre companies such as Druid in Galway, Red Kettle in Waterford, or the regional arts centres that have multiplied since the 1980s – the effect has often been not to reinforce the sense of a national theatre culture, but to create multiple differentiated regional theatres. For an audience in Navan, for instance, there is a difference between watching a play that has been produced in their home town at the Solstice Theatre by a locally based company, and one that is on tour from a national theatre based in the capital, just as, for an earlier generation, there was a difference between watching a play that had originated in Ireland, and one that was touring from England, or from the United States. In other words, the spread of physical spaces for theatre around the national space did not necessarily reinforce the idea of a national theatre; it could, in fact, have the opposite effect, highlighting regional difference over national solidarity. Second, just as there is little to stop a book, once printed and in circulation, from migrating beyond the imagined space of the nation (or the jurisdictional space of the state), once a theatre production is on the road, there is every reason to continue beyond the bounds of the nation in search of new audiences. In the same interview in which Stephen Rea spoke of touring regionally around Ireland with Field Day, he spoke of being ‘very proud’ of the fact that, in his view, Field Day had made it easier for Irish plays to transfer to London. ‘It’s now considered normal, and the traffic of actors between Dublin and London, and Belfast and London is very simple and very easy, but it wasn’t then . . . Field Day had a lot to do with that.’28 Similarly, in the 1990s, Druid began a practice of premiering their plays in Galway (at the Town Hall Theatre) and, within a few days, opening in London (often at the Royal Court), and have since built up audiences in New York and Australia. Other companies based outside of Dublin have followed similar patterns of opening in their regional base, playing festivals in Perth, New York or Edinburgh, and only then, if at all, staging a Dublin run.

‘The question as to whether there can be such a thing as “national theatre” is a salient one,’ remarks Read:

That a theatre exists that operates under the aegis of a national title cannot be questioned. Nor can the very real material and spiritual effort and investment that have been directed to that entity. But there is a contradiction in the idea, and it remains an idea, of a theatre reflecting something which is in itself in good measure ‘imagined’.29

In 1784, on Dublin’s Fishamble Street (less than a hundred yards away from the Smock Alley Theatre), a theatre building opened proclaiming itself to be the National Theatre Music Hall: this would be the first (but not the last) time that an Irish theatre would describe itself as a ‘national theatre’. This first ‘national theatre’ in Ireland appeared less than two years after repeal of the Declaratory Act in 1782 created an independent Irish parliament, and the modern formulations of Irish cultural nationalism (and Irish republicanism) were taking shape. Any earlier than 1784 an Irish ‘national’ theatre would have been literally unthinkable, because the conceptual framework for thinking about the nation in terms of symbolic cultural institutions would not have existed. By returning to the moment at which the space of the nation was first produced, we begin to glimpse the source of the contradiction that Read notes, and of the paradoxes inherent in trying to align the perceived and conceived spaces of a national theatre. In Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson influentially argues that millions of geographically diffuse individuals, most of whom will never meet one another, come to think of themselves as a ‘community’, and ultimately as a ‘nation’, largely through the mediation of print capitalism. Anderson’s argument here is spatial, in that he imagines a geographically diffuse mass of individuals reading the morning newspaper, and thereby participating in ‘a mass ceremony . . . performed in silent privacy, in the lair of the skull. Yet each communicant is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands (or millions) of others of whose existence he is confident, yet of whose identity he has not the slightest notion’.30 This simultaneous ‘silent communion’ is one of the defining features of modern culture, Anderson argues, that allows an individual to share a bond of kinship with thousands or millions of spatially distant and anonymous others, facilitating the formation of ‘a national consciousness’.

As familiar as this argument is, aspects of it are worth developing in more detail, including the obvious point that, except in the case of linguistically defined nations such as Finland, there is nothing to stop print flowing promiscuously back and forth across borders, and thereby muddying the very concept of a national (as opposed to a state) boundary. Indeed, if we accept the point made by David Harvey and others, that the spatial orientation of capitalism is expansionist in an ever-extending search for new markets, whether in an earlier phase of colonial expansion or in a late capitalist phase of globalisation, it becomes apparent that a fatal flaw is built into the project of producing the national space through print. The same forces that bring it into being are constantly exceeding it, spilling out over the edges of the national territory and thereby puncturing its claims to authenticity or integrity – and this is equally true of theatre.

In Ireland, the role of theatre in producing the space of the imagined nation was both more central and more complex than that of either print or, indeed, broadcast media. Unlike copies of a newspaper, or a radio broadcast, a play in performance takes place in a clearly demarcated space at a clearly defined time. The audience for any given performance is limited to those people who are in the same place at the same time. Members of an audience are not, in Anderson’s phrase, an ‘imagined community’: they are a real, albeit temporary, community whose members’ relationship to one another is bounded by the temporal and spatial parameters of the performance as event. The audience is, as Blau would have it, initiated by the performance, and this in turn makes possible the work of producing the space. Hence, there is an argument to be made that theatre in performance can never be national, at least in Anderson’s sense of creating a simultaneous national field in the case of radio (or, in the case of print, a field with what we might call a ‘simultaneity effect’). Theatre takes place in a particular place, at a particular moment, before a community that is not imagined but is real (and hence is constrained by the size of the space). To put it another way, there will always be a disjunction between the perceived space of performance and the conceived space of the nation. In terms of the perceived space, theatre is not national at all; it is local.31

If theatre in performance creates an event that is by definition local, why is theatre – particularly Irish theatre – so often considered in the context of the national? Theatre in performance may actively resist many of the features of print that make it so conducive to the creation of a national consciousness, but this does not prevent the theatrical experience from being translated into print, radio, and online information sources. The publication of reviews and play scripts, and the accumulation of these sources in theatre histories reconfigures the temporally and spatially specific form of performance into the temporally and spatially diffuse form of print. Reading a review of a play, a dramatic script, or a theatre history involves sharing with those geographically distant and anonymous others that sense of ‘communion’ of which Anderson speaks, producing an imagined community. In this regard, theatre can only really be national at a remove. As Alan Filewood writes of the idea of a Canadian national theatre, where sheer geographical vastness makes the conceived space of a national theatre even less realisable (or, indeed, imaginable), a national theatre ‘in fact exists only in the nostalgic space of its own imagining . . . In many cases, it was not the performance per se but its critical reception as circulated amongst an influential elite of engaged peers that mattered.’32

Thinking about theatre space in this way brings us some way towards the ‘postpositivist theatre history’ for which Bruce A. McConachie called in 1985, one that takes seriously the idea that ‘social-historical roles, actions and perceptions constitute the fundamental stuff out of which theatrical events emerge’.33 In particular, McConachie has gone on in his later work to suggest that the spaces produced by a given theatre culture can be understood in relation to a particular historical mindset, or way of seeing the world. Focusing on the idea (and, indeed, the policy) of ‘containment’ in the USA during the Cold War in the 1950s, he writes that ‘“containment” was as ubiquitous in the dominant culture as was the spatial relations schema of “balance” in the culture of Enlightenment France’.34 He points to the work of Thomas Postlewait, who noted, in relation to the plays of Tennessee Williams, that Williams generally creates ‘three spatial realms that operate visibly and thematically in his plays: an enclosed space of retreat, entrapment, and defeat, a mediated or threshold space of confrontation and negotiation, and an exterior or distant space of hope, illusion, escape, or freedom’.35

A comparable spatial analysis of Irish theatre in the late nineteenth century would reveal that, as the post-Famine diaspora was spreading out across the world, Irish theatre had a spatial orientation that was likewise expansive. In this period Irish theatre was being integrated into an international theatre system based around large touring productions. The stages of the theatres these productions used were designed to produce rapid changes of large-scale spaces, which emphasised not only their depth and size, but their capacity for transformation. In effect, these stages produced a theatrical space that codified the expanding international spaces of the theatrical tour, whose parameters were sketched in railroad lines and steamship routes, and which followed the trajectory of capital to penetrate ever larger markets. The spatial orientation of this theatre, in other words, was centrifugal. Because the form was not unique to Ireland, the Irishness of Irish plays written for this globalised theatre had to be recognisable as Irish from Sydney to New York, from Paris to Dublin. As a consequence, the aesthetic of this form of theatre was primarily visual, producing a represented space of the nation that was visual, expansive and transformational. A play such as Dion Boucicault’s The Colleen Bawn (1860) could not simply refer to the lakes of Killarney, and assume that audiences around the world could imagine them; they had to be shown, produced on a stage that foregrounded its own height, depth and speed of transformation.

This theatre of visible space stands in marked contrast to the early Abbey Theatre, and Yeats’s stated desire that to ‘restore words to their sovereignty we must make speech more important than gesture upon the stage’.36 The name of the original organisation founded by Yeats – the Irish Literary Theatre – and the resounding opening of its manifesto, make clear the linguistic focus: ‘We propose to have performed in Dublin in the spring of every year certain Celtic and Irish plays, which whatever be their degree of excellence will be written with a high ambition, and so to build up a Celtic and Irish school of dramatic literature.’37 From the outset, the spatial scale of this theatre was small, both in the physical dimensions of the stage and in the audience that Yeats imagined, and this continued to be a feature of its successor organisations for a number of years. ‘It is a necessary part of our plan’, he wrote in 1904, ‘to find out how to perform plays for little money, for it is certain that every increase in expenditure has lowered the quality of dramatic art itself, by robbing the dramatist of freedom in experiment, and by withdrawing attention from his words and from the work of the players.’38 Moving from a theatre of visibly expansive space (which had existed in the nineteenth century) to a theatre of language had the effect of detaching the perceived from the conceived, in which there would always be more on the stage than could be seen. As Richard Allen Cave puts it, in Yeats’s early plays ‘visual austerity links with imaginative richness’. In plays such as Yeats and Lady Gregory’s Cathleen ni Houlihan (1902), he argues, the door in the stage set is not simply ‘the actors’ means of entering and leaving the playing space’ but is also the focal point in the play’s ‘spatial dynamics’ as the ‘imagined offstage world in these plays comes in time to be as important to the resolution of the dramatic action as what is depicted onstage by more traditional means’.39

Likewise, Alice Milligan’s The Last Feast of the Fianna (1900), produced by the Irish Literary Theatre, may have been constrained by technical and economic considerations, but the spaces it evokes extend significantly beyond anything that could be physically produced upon the stage in any literal representation: ‘A banqueting hall in the house of Fionn Mac Cumhal. The warriors of the Fianna are seated on benches round a fire which is in the centre of the floor. Behind the fire through an open door is seen a moonlight space of sea.’ In performance, diegetic references add significantly to this evocation of another spatial dimension as Oisín looks out and points. ‘Look! On the golden, curving strand I see a wave burst in foam. It is not a wave but a white horse, and a graceful woman is the rider.’ The final speech by Niamh only confirms that the spatial conception of this play, even if limited in absolute visual expression, extends into another dimension altogether:

Over the next decade, Yeats began working with the designer Edward Gordon Craig to create a series of moving screens that could be pivoted, rotated and folded to create instant transformations of stage space in the quest to find a form for making the invisible visible. ‘We shall have a means of staging everything that is not naturalistic,’ Yeats wrote excitedly to Lady Gregory on 8 January 1910, ‘and out of this invention may grow a completely new method even for our naturalistic plays’.41 As Eugene McNulty points out, this interest in creating non-naturalistic stage spaces was profoundly ideological in that for ‘the Abbey playwrights (Yeats and Gregory most notably) performance of the mythic as a utopian space, in that etymological rendering of utopia as a “no-place”’ was attractive precisely because it took them away from the politically disputed ‘real’ space.42

As defined by the messianic Marxist Ernst Bloch, utopia is ‘that which has never entirely happened anywhere, but which is to come’. And he identified the theatre as the site of its genesis but not, crucially, its realisation for ‘it always has to extend beyond the evening of the theatre’ and into the space of society.43 Yeats’s belief in the power of dramatic poetry to enable utopia in Ireland was compromised by dramas which were often too opaque and esoteric to engage audiences, while the socialist alternative to his aristocratic vision, such as represented in the short-lived theatre career of Fred Ryan, was stillborn in a society whose utopian visions were for national rather than social liberation. Progressively, however, across the opening decades of the twentieth century, all impulses to engender any manifestation of a utopian space subsided in a desire to stage worlds which contained, rather than excited, the suggestion of better alternatives to those dramatised. As seen in Sean O’Casey’s Dublin Trilogy, by the time of the Free State in 1922, the characteristic note was one of mourning for places promised but never entered.

However, and as will become apparent in more detail in the next chapter, one of the defining features of Irish theatre space in the first half of the twentieth century would be a tension between this utopian offstage space and the constraints of a visible onstage space. Historically, we can begin to trace the outcome of that tension in the rapid consignment of the Craig screens to the Abbey prop store and the parallel ascendance of the realist box set in the repertoire. The dominant space on the Irish stage thus became the metonymic representation of the nation – the cottage kitchen. Although Rutherford Mayne is associated with the Ulster Literary Theatre rather than the Abbey, his plays demonstrate the all-pervasive presence of this particular stage space as, with variation only in the names of the owners, the set directions for three of his most successful plays read: ‘The action takes place throughout in the Kitchen of William John Granahan’s house in the County of Down’ (The Turn of the Road, 1906); ‘The action takes place throughout in the kitchen of John Murray in the County of Down’ (The Drone, 1908); ‘The action takes place in the kitchen of Ebenezer McKie’ (The Troth, 1908). And when, as in The Turn of the Road, there is a staging of the world beyond that of kitchen, its function is only to confirm the reality of the latter: ‘Door at back, opening to yard.’44 If the nineteenth-century touring theatre against which the early Abbey defined itself was expansive and centrifugal in its spatial orientation, and the space of which Yeats dreamed was utopian, and centrifugal in a different way, the realism that would dominate Irish stages in the middle decades of the twentieth century was, for the most part, centripetal, enclosed and bounded. It was still arguably a politicised space; however, its politics were no longer utopian.

As Una Chaudhuri has argued, naturalist theatre can be understood in spatial terms as a ‘theatre of total visibility’, which ‘adumbrates a specific relationship between the performance and the spectator, connecting them to each other with an ambitious new contract of total visibility, total knowledge. The promise of the well-stocked stage of naturalism is the promise of omniscience.’45 Even when the full set of theoretical contentions underpinning naturalism is not in play, the realist stage remains, to use Jean Jullien’s 1890 formulation, ‘a slice of life artistically set upon the stage’.46 McConachie suggests that in creating a world in which all that is can be seen, realism (and, indeed, naturalism) acted out the logic of omniscience that had been inherent in proscenium arch staging since the Renaissance:

Historically, the positioning of the audience in proscenium staging developed from the perspectivism of Renaissance painting. As idealized in the Teatro Farnese, for instance, the all-seeing eyes of the Renaissance Prince at the center of the auditorium gazed toward a horizon line behind the proscenium and fixed objects in space according to their distance from his vision. With the proscenium arch as a picture frame organizing stage objects for this type of panoptic vision, the West discovered a means of transforming the assumptions of Cartesian philosophy into theatre architecture and viewing experience.47

Realism thus follows through on the logic of this panoptic vision to produce a ‘theatre of total visibility’, which is the product of a fundamentally empirical attitude to knowledge that implies that all that can be known, can be seen. As well as implying an omniscience of power, however, ‘total visibility’ suggests that all that exists in a culture is coherent and homogenous enough that it can be seen, at least synecdochically, in a single image. A culture in which it is felt that the heterogeneous, the complex, is impinging on its sense of unity could respond in a number of ways: one would be to close down all of those elements that could not be contained within a single frame; the other would be to acknowledge the image’s own inadequacy.

The dominant trends in Irish culture in the decades immediately after 1922 can be understood within these competing alternatives. Most obviously, as both the Irish Free State and the Northern Ireland state became increasingly aware of their own limitations, not only did enforcing those limitations became a matter of public policy: limitation was adopted as a defining characteristic of national identity. This was evident in aspects of public culture ranging from the Censorship of Publications Act (1929) to trade restrictions, to the adoption of an autarkic economic policy, with the result that, as Tom Garvin argues, ‘the notion of a static and unchanging order that was to be regarded as ideal was quietly accepted, gladly or fatalistically, by much of the population’.48 On the stage, the form of this ‘static and unchanging order’ was a stage space that was likewise bounded, and was readable at a glance: a country kitchen, largely devoid of the markers of either modernity or antiquity, a space that could provide the setting for a play located in any time over the past century or more.

Yeats’s experiments with the Craig screens may have been a dead end in the creation of an Irish spatial aesthetic, cut off with the curtailing of a utopian political culture. However, they suggest that a small stage with limited (or no) offstage space nonetheless had the potential to produce a theatrical space that, rather than reinforcing the inherent limits of the space, transcends them. This is one way in which to read the work of Micheál Mac Liammóir and Hilton Edwards in the Gate Theatre in the 1930s and 1940s. Edwards and Mac Liammóir began producing plays together in Dublin in the late 1920s, but found that the only available space for them was the Abbey’s second stage, the Peacock – a stage, as Mac Liammóir later wrote, ‘on which you could hardly swing a cat’: ‘so we decided we might as well throw discretion to the winds and be bold and daring for once, and we opened one night with Peer Gynt’.49Like the early stages on which the Irish Literary Theatre worked – the Molesworth Hall, St Teresa’s Hall, even the Abbey itself – the Peacock was a stage whose physical limitations were more pronounced than its possibilities, with a performance space only 6.3 metres across and 4.8 metres deep, raised a mere 0.5 metres from the auditorium floor. The Peacock stage was only technically a proscenium arch theatre, for there was no offstage space, the back wall of the theatre was not parallel to the front of the stage, and there was no way of making a backstage cross. The only way to give the stage the functionality of a full proscenium was to build a box set within the already tiny performance area, making it smaller yet again.

It was initially on this stage that Edwards and Mac Liammóir began creating scenic spaces that were neither mimetic nor bound by the limits of the stage in which they were produced. Their first production, that of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt in 1928, used two moving stair-shaped trucks, painted a solid black, which could be moved into different shapes – a valley, a pyramid, ocean waves – against an uplit sky-blue cyclorama; the effect, by all accounts, was to create a theatrical space whose expansiveness defied the actual physical limitations under which they were working. In the years that followed, working in the only slightly less restrictive space of the Gate Theatre in the eighteenth-century Rotunda Rooms, Edwards and Mac Liammóir would develop this expansive spatial sense into a distinctive art-deco-influenced style, particularly with productions of plays by Wilde and Sheridan. ‘Realism is not essential to drama,’ declared a contributor (probably Edwards) to the Gate’s short-lived magazine Motley. ‘For the theatre is not life. No realistic trimmings will make it so.’50 In other words, the same physical limitations that produced the confined domestic spaces of the peasant play in the Abbey (which in turn were to be replicated around the country in amateur productions) were equally capable, in the early Gate Theatre, of producing a non-representational, utopian theatre space. Where the theatrical space produced by the peasant drama of the Abbey was a space aware of its own confinement, barely acknowledging the dimension of depth in space, the theatrical space championed by Edwards and his collaborators at the Gate was (like the conceived Yeatsian space of the Craig screens) constantly breaking through limits, creating space that used three full dimensions to create an implicit critique of the determinism of physical space in the production of lived space. A space need not be as given; the theatre can make it otherwise through performance.

These two contrasting forms of Irish theatrical space can be mapped on to two contrasting conceived spaces of the nation. If the realism of the Abbey stage in the 1930s and 1940s produced the space of a nation defending its boundaries, the Gate constituted a differently imagined national space. Writing in Motley, in 1932, the playwright Denis Johnston proposed that a national theatre should exist not purely within the walls of theatre buildings, but should take the form of street processions, on occasions such as Easter, staging the spectacle of Irish history. At the same time, in its engagement with plays from outside of Ireland, the Gate was producing a conceptual space that refused to be constrained by geography or politics. In the same years that economic policies were restricting trade, and censorship was restricting the flow of non-Irish books, newspapers and films, the Gate was staging plays by writers such as Eugene O’Neill, Nikolai Evreinov, Karel Capek, Tolstoy and Goethe – producing a theatrical world that extended beyond the island of Ireland. ‘The “Gate” has not fettered itself by pseudo-national Shibboleths,’ wrote the playwright Christine Longford in Motley in 1932. ‘It has not tied itself to the letter of Nationality, which is death only too often to the spirit . . . No person or institution can justly claim to be international unless it is also profoundly national, or to be national while repudiating the best that the world has to offer for the nation’s good.’51

Between the restrictive space of the kitchen box set and the expansive space of the sky-blue scrim in the Edwards–Mac Liammóir Peer Gynt, it would be possible to trace a history of Irish theatre in the twentieth century as a dialectic of expansive and restrictive spaces. As we shall see in Chapter 2, the most important Irish plays since the beginning of the twentieth century have been those that have both produced and critiqued their respective spaces in the same gesture. Before moving on to that analysis, however, it is worth noting that arguably the National Theatre itself was responsible for the most extravagant renunciation of an enclosed, restrictive theatrical space when it moved into new premises in 1966. The original Abbey building had been destroyed by fire in 1951. Over the next fifteen years the architect Michael Scott, of the firm Scott Walker Tallon, who aligned themselves with the modernism of Mies van der Rohe, worked to create a brick cube on the original site that was the physical renunciation of tradition. As one member of the design team said at the time, ‘they tried to forget about every theatre built before’.52 The architect’s brief for the stage, as Scott understood it, was ‘to eliminate the feeling of disconnection between audience and players caused by the traditional proscenium arch’.53 If, as McConachie suggests, realism was the working through of the visual logic of the proscenium arch, the new Abbey stage (which nonetheless retained a modified proscenium) was intended to be a renunciation of that logic. As a result, the stage in the new national theatre was the very opposite of the contained spaces in which the Abbey aesthetic had been formulated. With a 22-metre-wide stage, extendable forestage, three large and flexible hydraulic traps, thirty counterweighted flies, hydraulic bridge, acoustic baffles, and a full lighting rig, the 1966 Abbey stage was designed for expansive transformations of space. A second space, the flexible studio of the Peacock, went even further in this direction, at least in terms of design, capable of being used in a variety of configurations (although in practice it was largely used as a small proscenium arch stage). However, rather than proving liberating, the stage of the 1966 Abbey has been challenging in terms of keeping the inherited repertoire alive: if the lived space of the Abbey in its early years was one in which limitations and constraints could be produced and transcended in the same gesture, the 1966 stage, by removing the limitations of the original space, also removed the tension that produced the possibility of their transcendence. From a spatial perspective, therefore, 1966 could be taken as the point at which the defining dynamic of Irish theatre space established in the early decades of the twentieth century gave way to a new version of the expansive spaces that had dominated the nineteenth-century theatre. Indeed, within a year of the new theatre opening, the Abbey staged its first production of a play by Boucicault, The Shaughraun (1874) in January 1967. At the time, it seemed like a return to the past; in retrospect, it may have been a premonitory glimpse of the globalised theatrical spaces that would emerge at the end of the century, as the defining, enclosed centripetal space of Irish theatre would come unravelled.