Introduction

The negative medical and health impacts of disasters disproportionately affect developing countries. As assistance arriving from outside the disaster zone is often delayed, survivors typically move toward the impacted area to provide assistance immediately after a disaster occurs. This is a common phenomenon and Fritz and Mathewson used the term convergence to describe this activity in 1957.Reference Albahari and Schultz 1 Decades later, this behavior and the role of disaster volunteers, in general, were the subject of further discussion following the 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in New York City (New York USA). Influenced by this and other events, a definition for convergent volunteerism emerged, put forth by Cone et al. as “the arrival of unexpected or uninvited personnel wishing to render aid at the scene of a large-scale emergency incident.”Reference Fritz and Mathewson 2 Other terms including spontaneous and unaffiliated also were used to describe convergent volunteers.Reference Cone, Weir and Bogucki 3 , Reference Koenig and Schultz 4

Regardless of the terminology, a general consensus developed, reflected in these referenced publications, that convergent volunteers could be detrimental to disaster management efforts. Examples reinforcing this perspective included the death from falling debris of a volunteer nurse who attempted to assist victims without wearing proper protective equipment following the Oklahoma City (Oklahoma USA) bombings in 1995.Reference Ciottone 5 In addition to safety, authors have cited other concerns associated with convergent volunteers, including: medical oversight; accountability; liability; patient tracking; interference with operations; appropriate training; and the depletion of critical infrastructure.Reference Fritz and Mathewson 2 , Reference Cone, Weir and Bogucki 3 , Reference Martinez and Gonzalez 6 Nonetheless, other examples exist where convergent volunteers proved valuable in the initial response phase. Such events include the Armenian earthquake of 1988 when most of the initial rescue was accomplished by local personnel using simple tools, and the Boston (Massachusetts USA) Marathon bombing of 2013 when bystanders had applied limb tourniquets to victims before the arrival of the on-site volunteer physicians.Reference Cook 7 , Reference Macintyre, Barbera and Smith 8 Due to the somewhat negative connotation associated with the term convergent volunteers, the authors will refer to this group by the more neutral term, spontaneous volunteers, during the rest of this paper.

In an attempt to manage spontaneous volunteers, organizations and investigators have devised measures and guidelines to include volunteers in the disaster response without jeopardizing the overall management effort.Reference Albahari and Schultz 1 , Reference Fritz and Mathewson 2 , Reference Mitchell 9 - 11 These guidelines, however, are based on the requirement that governments or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) assume responsibility for disaster management upon arrival and would subsequently supervise volunteers, limiting them to specific tasks. These recommendations do not acknowledge the possibility that spontaneous volunteers could have utility and value unto themselves as independent entities and enhance community resilience. The controversy over the role of spontaneous volunteers remains unresolved. Until recently, no example existed of spontaneous volunteers providing an organized, independent, sustained, and effective response to a disaster that would meet international standards.

In August of 2013, heavy rains resulted in severe flooding around Khartoum in Sudan, causing a widespread disaster. An estimated 182,500 people were affected. 12 A group of spontaneous volunteer Sudanese youth, dissatisfied with the inadequate government response, formed a community-relief initiative called “Nafeer,” which translates to “a call for collective action” in Arabic. Nafeer effectively utilized social media to highlight the plight of people affected by the floods and directly provide disaster relief. It carried out several activities in flood-affected areas in Khartoum, acquiring local and international recognition. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA; New York USA and Geneva, Switzerland) praised the achievements accomplished by Nafeer. 13 The initiative was also featured in the New York Times. 14

The emergence of Nafeer potentially challenged the current perspectives surrounding the value and role of spontaneous volunteers still held by many in the disaster management community. Nafeer had complete autonomy in managing their disaster activities. The authors could find no evidence of a similar response by spontaneous volunteers that has previously been documented in the literature in which such a group demonstrated this level of organization and effectiveness in delivering aid. As such, an investigation ensued and described the disaster response adopted by Nafeer in flood-affected areas of Khartoum state, Sudan in 2013. Investigators then attempted to benchmark their response by evaluating its conformity to the core and minimum standards in essential health services as outlined in the Sphere Handbook. The Sphere Project was initiated in 1997 by a group of NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (Geneva, Switzerland) to develop a set of universal minimum standards in core areas of humanitarian response. The aim of the Sphere Handbook is to improve the quality of humanitarian responses by NGOs in situations of disaster and conflict, and to enhance the accountability of the humanitarian system to disaster-affected people. It’s also meant to serve as a monitoring and evaluation tool. The Handbook is the product of the collective experience of many people and agencies and is being updated periodically with its latest edition in 2011.Reference Kushkush 15

Methods

This investigation is a retrospective, descriptive case study involving: (1) interviews with Nafeer members that participated in the disaster response to the Khartoum floods in August of 2013; (2) examination of documents generated during the event; and (3) subsequent benchmarking of their efforts with the Sphere Handbook. Volunteers who held top administrative positions within Nafeer were identified through the organization’s social media accounts. They were subsequently contacted to request their participation and also were asked to identify additional leadership members and other individuals whom they thought would provide information relevant to the study. Those individuals, in turn, also were contacted and invited to take part. Members who agreed to participate were requested to provide all documents in their possession relating to Nafeer. Documents obtained were then reviewed and classified. Duplicates were identified and only one copy was included in the study. Participants were asked to describe their involvement with Nafeer and answer questions. This process involved several techniques: face-to-face interviews in Khartoum; Skype (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, Washington USA) meetings; phone calls; social-media messaging systems; and e-mails. One author (AA) traveled to Khartoum in June of 2015 and spent one month there specifically to gather data. Members’ statements were cross-referenced with the information present in the documents obtained, and any data that weren’t supported by these documents were subsequently discarded. Statements given by participants that contradicted each other also were discarded. Lastly, a summary of facts was assembled and presented to the participating members for final validation. This validated summary was then accepted by the authors. No formalized scripted interview or data collection tool designed prior to the study was employed by investigators. Previous review articles summarizing techniques for qualitative studies supported this approach. 16 , Reference Choo, Garro, Ranney, Meisel and Guthrie 17 Questions posed to subjects included their role in the response, how efforts were coordinated and managed, what types of aid were delivered, methods and sources of funding, and organizational structure.

Following collection and verification of the data, investigators compared Nafeer’s response with the Sphere Handbook’s six core standards, as well as the 11 minimum standards in essential health services. The core standards are general standards shared by all sectors involved in a humanitarian response, while the essential health service standards are rather technical standards dealing with the provision of health services to the affected population. The authors felt these guidelines represented the best “gold standards,” or benchmarks, available and were the most relevant to the purpose and nature of Nafeer’s activities. Nafeer’s compliance was compared with each benchmark based on the number of key indicators the organization’s response fulfilled for each standard or service. A standard was considered fulfilled if all of its key indicators were achieved, and partially fulfilled if at least one but not all of its key indicators were achieved. Conversely, a standard was deemed unfulfilled if none of its key indicators were achieved. If insufficient data existed to make this determination, the standard was considered unfulfilled. Finally, the number of Sphere standards fulfilled, out of the total of 17 standards included in the study, was calculated to determine the degree of conformity of Nafeer to the Sphere Handbook.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the European Master in Disaster Medicine (EMDM). This is a formally recognized Master’s program within the European Union and is jointly managed by two universities: the Università degli Studi del Piemonte Orientale in Italy and the Vrije Universiteit Brussels in Belgium.

Results

All seven leadership members of Nafeer’s Coordination Committee were contacted. Six agreed to participate in the study and provide documents, statements, and answers to questions. Ten other members were identified by the leadership as potential participants, five of whom agreed to enroll in the study. The number and classification of documents provided by the participants are listed in Table 1.

Table 1 Documents Obtained and Their Classification

Nafeer officially commenced its activity on August 2, 2013 with basic field-reporting of damage through its social media accounts. As more volunteers joined the initiative, Nafeer rapidly expanded and transformed from an initial small group focused primarily on real-time data collection to a community-led program providing aid to the disaster-affected population. It operated over a total period of 42 days, officially ending its operations on September 12, 2013. In total, Nafeer registered over 1,000 volunteers. However, it was not possible to verify the exact number of participants or all the details of their activities.

Goal and Activities

As its initial objective, Nafeer sought to determine the needs of the population impacted by the flood. It carried out a needs-assessment which identified both the essential requirements for the organization as well as those of the affected population. This needs-assessment was updated regularly and was the foundation on which Nafeer built its strategy, constructed its activities, and devised its plan of action. Nafeer’s goal was “to help fellow Sudanese who were affected by the flash floods and heavy rain that hit different parts of the country [Sudan] in August 2013.” Nafeer’s activities included: food provision; delivery of basic health care; environmental sanitation campaigns; efforts to raise awareness of the services Nafeer offered and the evolving status of the disaster; and construction and strengthening of flood barricades. Although Nafeer extended its activities to states other than Khartoum, the details regarding these activities were not available and were not included in the draft final report of Nafeer. It’s also unclear if the cost of its operations in other states was included in the final financial report.

Initiative’s Structure

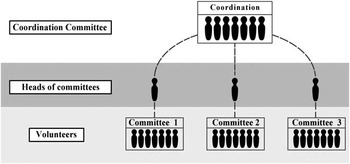

Nafeer adopted a flat-management structure, dividing itself into 14 committees, where each committee essentially functioned as an independent entity. A Coordination Committee was in charge of liaising between all committees (Figure 1). Names of Nafeer’s committees and their responsibilities are listed in Table 2. Members of Nafeer came from diverse professional backgrounds, including employees of corporations and NGOs, medical practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and university students.

Figure 1 Chart Illustrating the Organizational Structure of Nafeer.

Table 2 Nafeer Committees and Their Responsibilities

Nafeer utilized social media to achieve several objectives: bring attention to its cause, coordinate delivery of aid, and receive information about flood-affected areas. It also obtained a dedicated phone number that permitted the public to lodge reports. These reports were subsequently verified by Nafeer. More than 300 reports were received. However, the exact number, location, and nature of these accounts could not be confirmed. An on-line crowd map was created cataloging reports of floods, flood-related deaths, or any damage caused by rising water. This information also could be submitted via smart phone applications. Nafeer coordinated its activities with other NGOs working to help flood victims. It provided NGOs with volunteers, redirected redundant in-kind donations to them, and coordinated aid distribution in areas covered by the NGOs to avoid distribution overlap. Coordination also took place locally with the affected population. The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF; New York USA) provided Nafeer with input regarding the nature of food items to be distributed in a humanitarian disaster response. Further details of the coordination efforts with the community and other NGOs were not available.

Nafeer recruited volunteers and then organized training sessions and provided psychological support for them. The United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA; New York USA) helped Nafeer in training its volunteers. The UNFPA also lent them four cars for a month and provided them with hygiene and pregnancy kits to distribute. Ahfad University for Women (AUM; Omdurman, Sudan) also trained volunteers in psychological first-aid. Further details regarding the training offered by the UNFPA and AUM could not be found.

Nafeer used crowd-sourcing to fund its activities, receiving donations locally and internationally through its representatives outside Sudan. It also received in-kind donations. Nafeer’s total budget was US $328,097, of which 12% was spent on administration.

Achievements

The achievements of Nafeer, listed in its draft final report, include the distribution of aid items outlined in Table 3. Nafeer distributed aid in seven different localities. The activities of the Health and Sanitation Committee included two health days which took place one week apart. These health days included mobile medical and dentistry clinics supported by a mobile laboratory and pharmacy. They also included environmental sanitation campaigns. During the first health day, 613 patients were seen. Data regarding the classification of these patients by presenting complaints, diagnosis, or treatment were not available. Similar data for the second day also were not available. The Health Committee was also a member of a Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene task-force that also included UNICEF, Khartoum state Ministry of Health, Khartoum state water corporation, and World Vision (Monrovia, California USA). As part of this program, 103 Nafeer volunteers were trained on specific hygiene promotion messages, communication skills, and water chlorination techniques. These volunteers were later assigned specific work locations, but the partnership with Nafeer was terminated by the task-force five days after implementation. The Engineering Committee managed to construct and maintain flood barricades, but data on the number and distribution of these barricades were not available. These barricades, in some areas, were built in collaboration with the Sudanese Red Crescent Society and an organization called Sadagat. The latter is another NGO that worked closely with Nafeer.

Table 3 Items Distributed by Nafeer and Their Quantities

a Exact contents of a food bag is unavailable.

b The number of items in a box is unavailable.

c The number of bottles in a packet is unavailable.

End of Nafeer Activities

Nafeer operated independently for 42 days. Initially, the government of Khartoum state sought to restrict its activities. Later on, it threatened to terminate Nafeer’s operations under the pretext that the organization was an unregistered entity. Furthermore, if Nafeer were to continue its activities, it would have to register as an NGO. Nafeer maintained its position as an unregistered, community-led initiative, and saw the move to require registration as an NGO unwarranted. Fearing for the safety of its members, Nafeer decided to cease operations in order to avoid any altercation with the government’s well-known security apparatus. Nafeer decided to donate the balance of its budget to the registered NGO Sadagat, which Nafeer leadership trusted.

Nafeer and the Sphere Standards

Nafeer completely fulfilled three of the Sphere Handbook’s six core standards and partially fulfilled the other three. None of the essential health services standards were fulfilled. A list of the Sphere standards included in this study, their corresponding key indicators, and the authors’ consensus on their fulfillment are found in Table 4.

Table 4 Sphere Standards, Their Corresponding Indicators, and Authors’ Consensus on their Fulfilment

Discussion

After disasters, populations frequently experience delays in receiving aid from outside response organizations. Hurricane Katrina (Gulf Coast USA), the 2015 Nepal Earthquake, and the Ebola outbreak are examples. The emerging concept of community resilience is helping to address this shortfall by emphasizing development of local preparedness. One resource available to support a disaster response is citizens who spontaneously volunteer. However, the current published guidelines dealing with spontaneous volunteers are based on expert consensus, have not been validated, and were in large part developed before the emergence of the community resilience concept. They advocate perspectives characterizing such individuals as well-intentioned but ineffective and possibly dangerous. The guidelines restrict volunteers to pre-defined roles under the direct supervision of disaster managers or formal organizations. In contrast, examination of Nafeer represents a valuable opportunity to evaluate the role spontaneous volunteers can play in disasters when circumstances create the opportunity for an independently managed humanitarian response. Such circumstances occur frequently in Sudan and other developing countries. Prior to the creation of Nafeer, the absence of a rapid response by established disaster organizations have frequently left disaster-affected population without aid. It appears that Nafeer succeeded in rapidly transforming from a small group of volunteers to an organized and effective community-led initiative delivering aid to disaster victims. Not only did they succeed in providing access to basic medical care, but were in position to offer more sustained support such as psychological first aid and public health measures (ie, water, sanitation, and infrastructure). This last resource is particularly important as many individuals survive the initial disaster only to die later due to lack of access to basic public health resources such as shelter and clean water. Nafeer also successfully acquired and effectively managed substantial funds, spending 88% of donations on its activities. This figure is remarkably eight percent higher than the ideal percentage recommended for NGOs by the World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations (New York USA).Reference Ranney, Meisel, Choo, Garro, Sasson and Guthrie 18 Nafeer succeeded in bringing together a diverse group of students and professionals of different backgrounds, many of whom had not worked in the humanitarian sector before. It attracted national and international attention from both the public and the media to the plight of the disaster-affected population. Nafeer achieved all of this in six weeks, a relatively short period of time, and without any reported damage to property or personal injury to staff and its target population.

Structurally, Nafeer’s flat-management approach initially succeeded in creating an environment that enabled a diverse group of members to work together and offered them the autonomy needed to make decisions quickly. Its use of electronic platforms and social media to collect data and coordinate the organization’s response proved highly effective. However, as the number of committees and their associated responsibilities grew, the flat management structure actually inhibited the decision-making process, resulting in long meeting hours and increased frustration among its leadership. It is hard to predict how Nafeer would have evolved structurally if it had continued operation without pressure from the state government to cease activities.

Limitations

The main limitation faced while studying Nafeer was the lack of documentation required to facilitate the measurement of Nafeer’s conformity to the Sphere standards. Many of the statements provided by the members could not be verified by the documents provided, and therefore, were discarded. In addition, the members interviewed were asked about events that occurred two years previously, thus introducing the possibility of memory bias. Nafeer did not manage to write a final report, only a draft final report. This was due in part to the abrupt disbanding of the organization. The draft document is deficient in several aspects. Nafeer, itself, acknowledged in the report that the amount of aid items distributed was under-reported due to poor documentation during the early days of operations. Missing data required to evaluate Nafeer according to the Sphere standards were either not collected by Nafeer or unverifiable. All of the subjects interviewed did not have any knowledge of the Sphere project or its Handbook during their involvement with Nafeer.

The question of how to evaluate Nafeer’s achievements in delivering aid is a complex one. Besides its poor documentation, which partly caused the loss of significant amount of data necessary for its evaluation, Nafeer did not set specific objectives for itself based on which data elements (indicators) should be identified and subsequently measured. Even though the Sphere Handbook was chosen to benchmark Nafeer’s efforts, a specifically crafted template does not exist for evaluating community-led initiatives in disasters. The aim of the Sphere Handbook is to “improve the quality and accountability of the humanitarian response” by NGOs.Reference Kushkush 15 Although it does state that it can be used for monitoring and evaluation during the humanitarian response, it doesn’t specify an objective method to measure conformity to its standards. In addition, the authors of the Handbook envisioned using it to evaluate established humanitarian aid programs, not the activities of spontaneous volunteers. Lastly, it states that “conforming with Sphere does not mean meeting all standards and indicators; the degree to which agencies can meet standards will depend on a range of factors.” Indeed, the authors agree that the Sphere Handbook did not consider a range of both internal and external factors at play during Nafeer’s humanitarian response. The Sphere Handbook was simply not designed for community-led initiatives and showed significant limitations in effectively measuring groups such as Nafeer. It does not acknowledge how the negative impact of political forces influenced Nafeer’s response and how these forces led to the abrupt cessation of response activities six weeks after they began. It also does not take into account the limited legal protections and resources available for such an initiative. It is, therefore, understandable that Nafeer could completely fulfill only three standards and partially fulfill another three out of the 17 examined. Of the 53 indicators measured that comprise the 17 standards, Nafeer successfully met 20. Nonetheless, the authors acknowledge the Sphere Handbook remains the most widely-recognized benchmark for humanitarian interventions produced collectively by major international NGOs and is the best “gold standard” available. In the search for a template to evaluate Nafeer as an aid-providing initiative, it was not possible to find a better suitable alternative.

Conclusion

It appears that independent, community-led initiatives, implemented by spontaneous volunteers in countries where disasters can leave victims unaided, potentially can play a significant role in the humanitarian response and enhance community resilience. As the circumstances leading to the creation of Nafeer arise frequently in Sudan and in other developing countries, initiatives like Nafeer should be more thoroughly investigated and the possibility of incorporating them into the overall humanitarian response, both at the planning and implementation levels, be explored. Should the model illustrated by Nafeer prove robust, relevant bodies should consider issuing separate guidelines targeting spontaneous volunteer organizations to more effectively measure and guide this potential source of aid.