Introduction

Western societies are increasingly polarizing. While there is mixed evidence on the extent to which citizens have become more extreme and divided in their political opinions – with some scholars finding proof of ideological polarization (Abramowitz and Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Webster and Abramowitz, Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017) and others rejecting this trend (Mason, Reference Mason2015; Draca and Schwarz, Reference Draca and Schwarz2021) – it is a well-established finding that citizens increasingly dislike and, in the worst case, even outright despise opposing political groups. In this light, scholars often speak about affective polarization, a trend where citizens develop a strong affective connection towards their own political side – the political in-group – and, perhaps even more worrying, increasingly dislike and feel animosity towards people with opposing political allegiances – the political out-group (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012). This dislike between political opponents often exceeds existing negative feelings between members of different ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups (Mason and Wronski, Reference Mason and Wronski2018; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018). For a long time, affective polarization scholars focused mostly on the USA (Iyengar and Westwood, Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Mason, Reference Mason2015, Reference Mason2016), wondering whether this phenomenon is exclusive to this country or to two-party system contexts. Recently however, investigations increasingly show that affective polarization is widespread, affecting democracies globally, both two- and multi-party systems alike (Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021; Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021a).

For democratic societies, growing levels of affective polarization, and particularly the growing hostility between opposing partisans, are highly problematic and disruptive, as they are linked to numerous potential negative consequences (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018). Politically, it could result in citizens who no longer speak with and listen to the political ‘enemy’. In the worst case, this may even cause citizens to reject election results (Hetherington and Rudolph, Reference Hetherington and Rudolph2015), as seen after the recent American elections of 2020. For coalition formation in multi-party systems, it can also pose problems as it may make elites unwilling to compromise with political opponents when they know they will get punished for it by their own followers who strongly dislike these opponents (Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020). Moreover, the animosity between political groups does not stay limited to the political arena, but tends to spill over to the social domain as well. Research has demonstrated negative consequences of partisan hostility in the job market, in economic behaviour, and even in people’s private dating life (Gift and Gift, Reference Gift and Gift2015; Huber and Malhotra, Reference Huber and Malhotra2017; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). On the long term, this trend therefore not only hurts the democratic legitimacy of a political system, but also erodes crucial social trust and cohesion within society.

Although scholars on affective polarization agree on its widespread occurrence and negative consequences, other questions still remain unanswered or prompt discussion. One such question is to what extent affective polarization, and specifically the hostility between opposing party electorates, are rooted in ideological conflict. Some scholars argue that the phenomenon mostly has an ideological basis and that the dislike between political opponents follows from their ideological disagreement (Rogowski and Sutherland, Reference Rogowski and Sutherland2016; Webster and Abramowitz, Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017; Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2021). Others, such as Iyengar et al. (Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019) and Mason (Reference Mason2013), however, claim that ‘affective polarization is largely distinct from the ideological divide’ (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019, p. 131). They point to group conflict theory and, while not ignoring that ideology still can play some role, argue that it is especially the salience of party identity as one’s social identity that drives the negative affect towards out-partisans. Identifying with a party makes people divide the political space into an in-group (our own party or parties) and an out-group (the other parties). Any such division automatically results in positive feelings for the in-group and negative feelings for the out-group (Billig and Tajfel, Reference Billig and Tajfel1973). According to this reasoning, even when political groups are not very ideologically different from one another, just being attached to a different political group or ‘tribe’ already results in negative feelings for the ‘others’ (Mason and Wronski, Reference Mason and Wronski2018).

So far, the discussion to what extent affective polarization is ideologically rooted has remained unresolved in the literature, partly because the field focused for too long solely on the USA (Rogowski and Sutherland, Reference Rogowski and Sutherland2016; Webster and Abramowitz, Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017; Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2021). Examining this question in a two-party system with only one political out-party electorate and therefore no variation in the ideological distance between electorates, makes it difficult to fully analytically examine the role of ideology in this context.

More recently, however, scholars have set out to study this question in (European) multi-party systems. Although findings show that social identity and partisanship do play a role in driving the negative feelings towards out-parties and partisans, they find that ideological differences equally (Viciana et al., Reference Viciana, Hannikainen and Torres2019 in Spain) or even more strongly (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018 and Reiljan and Ryan, Reference Reiljan and Ryan2021 in Sweden) explain these feelings. However, many of these studies focus solely on the affect towards the own party and the most disliked party, essentially reducing the complexity of a multi-party system back to only two parties or blocks (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018; Viciana et al., Reference Viciana, Hannikainen and Torres2019). Moreover, most focus on the negative affect and dislike towards political elites and/or parties rather than the affect towards fellow citizens (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018; exceptions include Viciana et al., Reference Viciana, Hannikainen and Torres2019, Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila, Reference Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila2021; Reiljan and Ryan, Reference Reiljan and Ryan2021; and Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021a). Yet, it is especially the reported and hypothesized negative effects of affective polarization on the level of citizens that drive most concerns. Moreover, as studies by Druckman and Levendusky (Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019) and Harteveld (Reference Harteveld2021a) show: evaluations of parties or elites and supporters are both conceptually and empirically very different, and correlate only moderately. This signals the importance of not only considering affect towards political out-parties and elites, but also to focus on feelings towards supporters of out-parties instead.

The present study contributes to this, whilst adding to the new and emerging body of literature studying affective polarization outside of the USA. We focus on the Belgian political context and use the analytical leverage this case provides to better understand to what extent affective polarization is ideologically rooted. Here, we focus specifically on the partisan hostility element of affective polarization, which, over time, increased more strongly than the positive feelings towards the in-group, and is more strongly driving the affective polarization trend (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila, Reference Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila2021). Belgium is a particularly well-suited case to answer this question as, due to its highly fragmented multi-party system, citizens have multiple political out-party electorates. Furthermore, importantly, there is strong variation in how ideologically close or distant these electorates are. This variation enables us to better tease out the role of ideology on the negative affect for out-party electorates, looking specifically at the perceptions of the different supporter groups, rather than working with one combined measure. In doing so, we can assess both the role of absolute ideological distance between citizens and different party-electorates, as well as the ideological distance citizens perceive between themselves and others. This way, we provide further insight into how affective polarization, and particularly out-group hostility, manifests itself in a multi-party system.

Group conflict theory vs. ideological conflict

Although polarization has been of central interest for political scientists, for a long time the field has focused on ideological polarization, the extent to which citizens become more extreme in their ideology (Abramowitz and Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008), or on elite polarization, the extent to which political elites are situated more at the political extremes (Dalton, Reference Dalton2008). It is only more recently that scholars have started looking at affective polarization. This type of polarization refers to a situation where citizens increasingly hold positive feelings towards their own party and its supporters, while disliking and even despising citizens with opposing political views (Webster and Abramowitz, Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017). Thus, in contrast to ideological polarization, affective polarization does not prescribe that citizens become more ideologically extreme and shift their political opinions further apart, but rather that political divisions form a stronger basis for citizens’ affective evaluation of certain groups (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012). However, there is disagreement in the literature about what lies at the root of it.

Within the field, we can broadly define two competing lines of research that explain what drives affective polarization, and particularly the negative feelings towards political out-groups. The first argues that these feelings find their roots in group-based conflict theory. According to this view, the dislike and hostility between different political groups are not per se based on their difference in opinions, as they sometimes do not even disagree very much over substantive political issues (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Mason, Reference Mason2015; Webster and Abramowitz, Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017). Rather, it is argued that affective polarization is the consequence of partisans’ different (emotional) group attachments and is actually somewhat comparable to supporters of different sports teams who loathe each other purely on the basis of their identification with one of the teams. This perspective bases itself heavily on long-standing findings from social psychology on social categorization, which show that, when made salient, even very trivial criteria – such as for instance being randomly divided in a red or a blue group – can already strongly foster group identities and result in the formation of an in- and an out-group (Billig and Tajfel, Reference Billig and Tajfel1973; Bigler et al., Reference Bigler, Jones and Lobliner1997). The us-vs.-them feelings that arise from this in- and out-group categorization spark animus and result in more negative and denigrating feelings towards the out-group (Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979).

Following this logic, affective polarization then especially takes place when party identities, or similar political identities such as ‘leftists’ vs. ‘rightists’ (Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021a), become more salient. As people identify more strongly with a party, the partisan division becomes a stronger criterion around which people form in- (i.e., supporters of their own party) and out-groups (i.e., supporters of other parties). These subsequently trigger positive feelings towards their own group and negative or even hostile feelings towards the out-party electorate. Ultimately, this literature strand therefore attributes the rising trend of affective polarization in many countries, mostly to developments such as more negative elite rhetoric in campaigns (Marien et al., Reference Marien, Goovaerts and Elstub2019), the surge of partisan news coverage (Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2013), and selective exposure on social media (Stroud, Reference Stroud2010), all of which increase citizens’ party or political identity and thus ultimately results in higher levels of affective polarization.

A second line of research rather argues that affective polarization, and the hostility between political opponents, is mostly embedded in the different ideological issue positions of political groups. Partisan hostility is thus clearly a function of the ideological conflict and differences between electorates (Rogowski and Sutherland, Reference Rogowski and Sutherland2016; Webster and Abramowitz, Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017; Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2021). According to this school of thought, it is not primarily the identification to a different party itself that creates a dislike for opposite party supporters, but rather the fact that these politically other-minded citizens hold different opinions, or at least support a political party that defends different ideological issue positions. The negative affect towards certain partisan groups is therefore not largely the result of social identity mechanisms, where the out-group is automatically perceived as ‘bad’, but rather comes into existence when citizens also disagree with one another politically and therefore feel ‘threatened’ by political opponents and/or ‘despise’ them for holding and supporting such ideas (Rogowski and Sutherland, Reference Rogowski and Sutherland2016).

This can work directly, as the negative affect may follow from the fact that supporters of other parties hold different political ideas themselves. In this situation party support serves mostly as a cue for someone’s political opinions, as one may assume that the electorate of a party more or less takes the same ideological stance as that party. One may, for instance, infer that voters of a radical right party will also hold more radical right ideas themselves, even though in reality this will not always be correct. Yet, it may also work indirectly, where even when one does not automatically assume that all party supporters take the same (extreme) ideological position as the party they vote for, just the fact that these people support a political party that takes such an opposite ideological stance may already be enough to generate dislike. Nevertheless, in both instances, it is clear that the negative affect is rooted in ideological differences and increases as the ideological distance between different party electorates and parties becomes larger. Ultimately, this line of research explains the rising trend of affective polarization, and particularly the growing animus towards political opponents across democracies in the last 10–20 years, by the increasing ideological polarization of citizens and elites during that same period.

So far, the question on whether affective polarization is rooted in group attachments or ideological differences has remained unresolved, although the first empirical evidence more strongly supports the latter perspective. Reiljan (Reference Reiljan2020) for instance, utilizing electoral survey data of 22 European democracies and the USA, finds a strong correlation between levels of ideological polarization and levels of affective polarization in countries. Yet, this does not tell us much about the connection between ideology and a negative affect towards political opponents at the individual level. In another study, conducted in the context of post-Brexit UK, Hobolt et al. (Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021) show how affective polarization is not always and only linked to partisanship, but that identification with opinion-based groups (‘Leavers’ and ‘Remainers’) can stimulate group-based negative feelings as well. Others have used experimental studies, manipulating the ideological position of fictional political candidates, to test how this influences the affective evaluation of these candidates. These studies find that citizens are more negative towards political candidates of the opposite party when these candidates take a more extreme ideological position (Rogowski and Sutherland, Reference Rogowski and Sutherland2016; Webster and Abramowitz, Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017; Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2021).

Nevertheless, given that most of these studies have been conducted in the USA and/or have focused on two competing groups, it remains difficult to disentangle party effects and ideological distance from one another, as there is only one out-group. Scholars have set out more recently to conduct research in the context of the European multi-party systems, but these studies often still focus only on the most disliked party supporters (Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018; Viciana et al., Reference Viciana, Hannikainen and Torres2019), or, much like their American predecessors, focus on affection towards political parties or candidates (Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila, Reference Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila2021; Reiljan and Ryan, Reference Reiljan and Ryan2021, but for an exception see e.g., Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021a). However, affection towards political candidates or parties is not necessarily the same, neither conceptually nor empirically, as affection towards supporters (Druckman and Levendusky, Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019) and there is only a moderate correlation between the two.

To more clearly disentangle group attachment from ideology, this study therefore focuses on the Belgian multi-party system, a context where there are several (out-)parties, all with different ideological backgrounds, and where there is thus much variation in the ideological distance between different electorates. We focus specifically on the feelings towards supporters of out-parties, rather than feelings towards the out-parties themselves. Ultimately, if the negative affect towards opponents is purely driven by group attachment, we should find that in a multi-party system such as Belgium, citizens dislike supporters of parties that are not their own more or less equally (Figure 1, top pane). Or that alternatively – given that in multi-party systems citizens may actually identify with two or three parties simultaneously (van der Meer et al., Reference Van der Meer, van Elsas, Lubbe and van der Brug2015; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021) – there is at least a division in two clear blocks, where people equally like supporters of parties from the own block and equally dislike supporters of parties from the other block (Figure 1, mid pane). If, however, it is rather rooted in ideological differences, then we should find that hostility towards supporters of other political parties depends mostly on how far these parties are ideologically removed from them, and that voters become more hostile towards electorates of other political parties when the ideological distance with these electorates increases (Figure 1, bottom pane). Given the evidence from previous USA and European studies, we position ourselves in this second school of thought and expect that the negative feelings towards opponents, and by extent affective polarization in general, has a strong ideological basis. Ultimately, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Figure 1. Three models of affective polarization in multi-party systems.

H1: Citizens show higher levels of dislike towards supporters of other parties when the ideological distance to this group is larger.

As an additional test, we also investigate to what extent the effect of ideological distance on negative affect is moderated by ideological extremity and political interest. If affective polarization is indeed strongly rooted in ideological conflict, then we should find that the relation between ideological distance with an electorate and the dislike for this group will be stronger for citizens who occupy more extreme ideological positions. From the literature, we know that these citizens tend to be more ideologically invested (Rogowski and Sutherland, Reference Rogowski and Sutherland2016). Consequently, we would expect that they perceive the stakes of the political competition to be higher and feel more politically ‘threatened’ by opponents with a different ideology, ultimately resulting in a stronger relation between ideological distance and the dislike towards other party electorates. The same can be expected for citizens that are more politically interested, who are also more ideologically invested (Webster and Abramowitz, Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017). Additionally, politically interested citizens are more aware of the ideological similarities and differences between themselves and the other party electorates. If it is indeed ideological differences that drive the negative affect towards other party electorates, then a necessary prerequisite is that citizens also perceive these differences. We thus expect political interest to moderate this effect.

H2: The effect of ideological distance on higher levels of dislike is stronger for citizens who take a more extreme ideological position.

H3: The effect of ideological distance on higher levels of dislike is stronger for citizens who are more politically interested.

Data and methods

To test our hypotheses, we focus on the case of Belgium, a country traditionally characterized by a strong political centre and a history of consensus politics (DeSchouwer, Reference DeSchouwer2012). As a democratic corporatist model with a strong welfare state, Belgium serves as a representative case for other countries with similar characteristics, such as the Netherlands and Norway (Hallin and Mancini, Reference Hallin and Mancini2004; Brüggemann et al., Reference Brüggemann, Engesser, Büchel, Humprecht and Castro2014). In addition, the country has a highly fragmented multi-party system, where parties are divided both among ideological and linguistic lines. Concretely, Belgium is split up in two separate language groups: the Dutch-speaking region of Flanders and the Francophone region of Wallonia. Each language group can be considered to have their own party system, as citizens cannot vote for parties from the other language group. This linguistic divide has long been the most prominent societal cleavage in Belgian society, although Westwood et al. (Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018) show that it is now trumped by party affiliation. In the latest elections of 2019, 14 parties participated; seven for each language group. Appendix A (online) provides an overview of the parties and a description of their ideology. These elections of 2019 showed high levels of volatility: one-third of the Belgians did not vote for the same party they voted for in the previous elections (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, van Erkel, Jennart, Celis, Deschouwer, Marien, Pilet, Rihoux, Van Haute, Van Ingelgom, Baudewyns, Kern and Lefevere2020). This also means that there is more variation in party identity strength than in the USA, with certain voters identifying stronger with the party they voted for than others.

This highly fragmented multi-party system of Belgium, combined with variation in party identity strength between citizens, enables us to disentangle party label cues from ideological distance, or, put differently, to analytically distinguish the two mechanisms of group attachment and ideological conflict from one another. Furthermore, the presence of the strong linguistic divide between the Flemish and Walloons, enables us to further contextualize the intensity of party-based negative affect in a relative matter. As pointed out by Westwood et al. (Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018), juxtaposing partisan divides in a country against other societal divides can be helpful in gauging the comparative magnitude of these chasms.

For our analyses, we rely on the post-electoral wave of the 2019 Belgian National Election Survey (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, van Erkel, Jennart, Celis, Deschouwer, Marien, Pilet, Rihoux, Van Haute, Van Ingelgom, Baudewyns, Kern and Lefevere2020), which was conducted in the period of 3 weeks after the elections of May 2019. 3878 people completed this wave; 494 were located in Brussels (12.8%), 1965 in Flanders (50.7%), and 1418 in Wallonia (36.6%). We focus here on Flanders and Wallonia, the two largest Belgian regions (N = 3384), as questions about affective polarization were not asked in the Brussels region. The survey was administered by Kantar TNS through their online panel, participants being selected as good representatives of Belgian society.Footnote 1

To map the extent to which respondents like or dislike supporters of different political out-parties, we employ the so-called ‘feeling thermometer’ scale. Feeling thermometer questions are the most common measurement in the field of affective polarization (Druckman and Levendusky, Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019). With the thermometer participants use a slider to indicate whether they feel ‘cold’ and ‘unsympathetic’ (0°), ‘neutral’ (50°) or ‘warm’ and ‘sympathetic’ (100°) towards certain groups. In our survey, respondents were asked to indicate their feelings towards supporters of all the seven parties active in their own region and towards both Flemings and Walloons in general.

Next, we asked respondents about their own ideological position. Specifically respondents were asked to position themselves on a 0–10 scale of political ideology, 0 being most left, 10 being most right and 5 being centre. We realize that respondents could consider being ‘leftist’ or ‘rightist’ as part of their political identity as well. We therefore compared the aggregate scores of each party electorate with the 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) data, where experts were asked to position the parties on an ideological dimension (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2020). We find a strong correlation (r = .96), indicating that our question, at least to a large extent, captures the ideological position of the respondents.

Respondents were also asked to position supporters of the different political parties in their region on that same left-right scale. We use these ideological questions in two ways. First, they enable us to calculate the average left-right position of each party electorate and thereby allow to measure how ideologically distant party electorates are. An advantage of this approach is that this enables us to measure the party electorate ideological positions directly, rather than inferring it indirectly from the party positions, as most other studies have done so far (e.g., Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021a). At the individual level, we then create a measure of ideological distance between a respondent and each party electorate by taking the absolute difference between the left–right position of this respondent and the average left–right position of the electorates (objective ideological distance). Second, we also create a measure of the respondents’ perceived ideological distance from each party electorate by taking the absolute difference between a respondent’s own left–right position and the left–right position that the respondent themselves gives to the party electorate (subjective ideological distance).

With regard to our analyses, we start with a descriptive overview of the feeling thermometer and show for each party electorate how they feel about the other party electorates. This provides a first insight into the affection scores between the different party electorates in a multi-party system. Next, we take a more detailed look at the relationship between respondents’ feelings towards electorates of different out-parties and the subjective and objective ideological distance with these electorates. Concretely, we stack the dataset so that each respondent is present as a case fiveFootnote 2 (Wallonia) or six (Flanders) times, each time linked to a different out-party electorate present in their specific region.Footnote 3 As we are specifically interested in feelings of partisan hostility, we only focus on respondents’ ratings of electorates of the out-parties and therefore the combinations/dyads where respondents rate supporters of their in-party – operationalized as the party for which they voted in the federal elections of 2019 – are omitted from the dataset.

Because of the nested data structure – the five (Wallonia) or six (Flanders) dyads between a respondent and each out-party electorate are nested within the respondent – we run multilevel linear regression models with the feeling thermometer score towards each out-party electorate as dependent variable. As the main independent variable, we add the ideological distance between the respondent and the respective out-party electorate. We test our hypotheses with both the objective ideological distance measure and the subjective/perceived ideological distance measure. The advantage of using the subjective measure is that it enables us to directly model how ideologically distant a respondent perceives other party supporters to be. A drawback of the subjective measure, however, is that this measure could be partly endogenous since disliking a group may also result in perceiving this group to be more ideologically distant. To solve this problem, we run the same models with the objective ideological distance as a more exogenous measure to see if we obtain similar results. By taking into account both the objective and subjective measures we get a more robust test of our main hypothesis.

We also add two independent variables to the model that (indirectly) measure party identification and thus tap into the group attachment mechanism. Although we are aware that more elaborate survey items measuring party identity strength in multi-party systems have been developed (for instance Bankert et al., Reference Bankert, Huddy and Rosema2017), the dataset we use only contains one variable that could be used to measure party identification strength, although in a more indirect manner, namely the propensity to vote (PTV). Concretely, respondents were asked to indicate on a scale from 0 (never) to 10 (certain) for each party how likely it is that they would ever vote for that party in future elections. Here, we take the score for the in-party and assume that respondents that identify stronger with their in-party score higher on this PTV-measure. We also include a second measure of party identity, namely whether the respondent already planned to vote for the in-party in the first pre-election wave. As partisanship stability is seen as a core characteristic of party identity (see Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018), we assume that respondents that were already certain about their vote before the start of the campaign have a stronger party identity.

To test the second and third hypothesis, we also add political interest and ideological extremity to the model. Political interest is measured on a 10-point scale running from 0 (no interest) to 10 (very interested). A variable for ideological extremity is created by rescaling the left–right self-assessment so that 0 means ‘center’ and 5 means an ‘extreme’ position on either the left or the right (a score of 0 or 10 on the original left-right scale). Finally, we add several control variables (gender, age, education), as well as fixed effects for the different party electorates that have been rated, to account for the fact that the dyads are also nested at this level.

Results

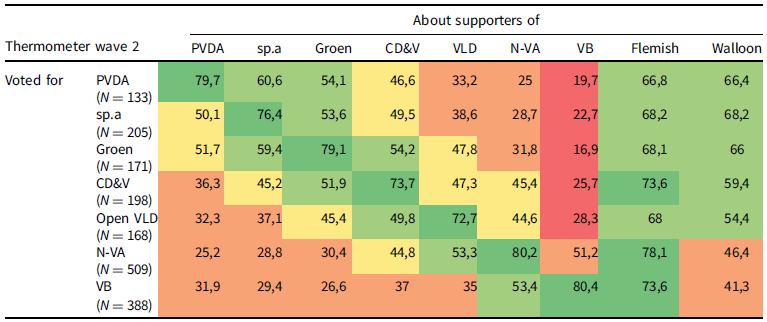

In Tables 1 and 2, we first turn towards the descriptive results of the thermometer measurement scores in both Flanders and Wallonia, and show for each electorate how they feel about the supporters of each of the parties in their region. In the tables, we sort the electorates based on the subjective left–right position they were given by respondents. Not surprisingly, the tables demonstrate that in both regions people generally give the highest score to supporters of the party they themselves voted for in the 2019 federal election. We also see that supporters of parties that are ideologically closer to their ‘own’ party receive moderately positive or more or less neutral scores. Supporters of parties that are ideologically further removed from their own party, however, receive much lower scores. In other words, voters of right-wing parties are quite positive about supporters of other right-wing parties, but display a negative affect towards supporters of more left-wing parties, and especially towards those supporters of the ideologically most extreme party on the left, the socialists (PVDA in Flanders; PTB in Wallonia). For the electorate of left-wing parties, the pattern is exactly reversed as they become more negative towards other electorates the more right-wing these are. Particularly in Flanders, we see that left-wing voters, and even voters in the centre, have strong negative feelings about supporters of Vlaams Belang, the ideologically most extreme right-wing party. These negative feelings are stronger than the reverse feelings of Vlaams Belang voters towards supporters of left-wing parties. We are not the only ones finding this asymmetrical pattern, as it has also been demonstrated in other countries (e.g., Reiljan and Ryan, Reference Reiljan and Ryan2021; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2022).Footnote 4

Table 1. Mean thermometer scores, Flanders

Note: Green cells designate higher scores in a row, red cells designate lower scores in a row.

Table 2. Mean thermometer scores, Wallonia

Note: Green cells designate higher scores in a row, red cells designate lower scores in a row.

As thermometer scores tend to tap into a more initial form of affect, rather than real-life consequences of negative feelings (Druckman and Levendusky, Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019), a corresponding measure of social distance was used as a robustness check. This measure shows similar, albeit slightly less outspoken results compared to the feeling thermometer scores, indicating a spill-over of out-party hostility to the social domain (see online Appendices B and C).

When looking at the scores, we can furthermore notice that in both party systems the partisan divide is stronger than the regional divide, in line with Westwood et al. (Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018). Voters are much more negative towards political opponents in their own region than they are towards residents of the other region. Even N-VA and Vlaams Belang voters – parties with a history of Flemish nationalism who are traditionally very critical towards Wallonia – are much more negative about supporters of Flemish left-wing parties than they are towards Walloon citizens. These differences are all significant at the P < .01 level. Although this suggests that the partisan divide is stronger than the regional divide in Belgium, the difference could also be partly driven by the fact that there are less social acceptability constraints on expressing hostility towards other partisans compared to expressing negative feelings to other regional or ethnic groups. Then again, Westwood et al. (Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018) reach a similar conclusion when conducting (more subconscious) trust experiments where the influence of social desirability is lower.

Taken together, the aggregate descriptives show that citizens do not dislike all out-party supporters equally in a multi-party system. Instead they become more negative towards supporters of other parties the further these electorates are ideologically removed from them. This gives strong initial evidence for our main hypothesis that partisan hostility is largely rooted in ideology rather than solely in-group attachments. This is also further supported when we calculate the correlation between the feeling thermometers scores that electorates give one another and the objective ideological distance between them, which is extremely strong. In Flanders, we find a correlation of r = −.83 (P < .01) between the affect score and ideological distance. In other words, here the ideological distance between two groups of electorates is an almost perfect prediction of the feelings these groups display to one another (at the aggregate level). In Wallonia, the correlation is slightly lower, but still high (r = −.70, P < .01).

To test our hypotheses more stringently, we next investigate the relation between (perceived) ideological distance and the affect towards supporters of a political party at the individual level, rather than at the meso-level as we have done so far. Do we find that respondents are more negative towards a group of party supporters when the subjective and objective ideological distance with this out-group is larger? To find out, we use the multi-level modeling strategy described earlier.

In model 1 (Table 3), we first regress the feeling thermometer score a respondent gives to the different out-party supporters on the subjective ideological distance from that group, controlling for several socio-demographic characteristics, political interest, and ideological extremity. The model demonstrates that there is a significant and strong negative effect of perceived ideological distance on the thermometer score. In other words, when citizens perceive a greater ideological distance between themselves and a party electorate, they also have more negative feelings towards this electorate. Specifically, the model shows that for each point that an electorate is perceived to be further away on the subjective ideological distance scale, the thermometer score that a respondent gives to a group of party supporters decreases by a striking 5.2 points (on a 0–100 scale). Of course, using the subjective measure of ideological distance does not fully exclude the possibility that the relationship may partly work reversed as well, and that a more negative affect towards a group may also cause people to perceive these groups as more ideologically distant. For this reason, we also run the same model with the objective ideological distance measure instead (model 6, Table 4). This model gives a similar result, with the objective ideological distance effect being even slightly stronger. These two models thus provide, first, support for H1 and suggest that partisan hostility has a strong ideological basis, with the negative affect between groups being the result of these groups disagreeing with one another politically.

Table 3. Ideology and affect – subjective ideological distance

* P < .05.

** P < .01; fixed effects for parties not depicted.

Table 4. Ideology and affect – objective ideological distance

* P<.05.

** P < .01; fixed effects for parties not depicted.

As explained in the theoretical section, another explanation behind negative feelings towards out-partisans may stem from group attachment and stronger feelings of party identification. For that reason, we next add the two variables measuring respectively party identity strength and party identity stability to our models to control for this alternative mechanism (model 2 and model 7). The models show no direct effect of partisan strength on out-group feelings. At the same time, we find that the other measure of party identity, party identity stability, does result in more negative feelings towards out-party supporters. Ceteris paribus, respondents who were already certain about their party choice before the start of the campaign, rate supporters of other parties on average four points lower. What we can also notice from these models is that the effects of both subjective (model 2) and objective (model 7) ideological distance remain stable when controlling for party identity strength and stability, and a comparison of the standardized coefficients – respectively −.520 (ideological distance) and −.083 (partisan stability) for the subjective model, and −.493 and −.098 for the objective model – suggests that the ideological effect is stronger than the party stability effect.

The measures of party identity vary at the respondent level, but, unlike the ideological distance measure, do not vary at the first, dyadic level. For that reason we perform a second, even stricter, test in model 3 and model 8 by adding an interaction between ideological distance and the two measures of party identity. This interaction serves two purposes. First, the two mechanisms of ideological differences and party identity may not be fully independent from one another, especially since some studies have shown that partisan identity can also partly influence citizens’ ideological positions (see for instance Kinder and Kalmoe, Reference Kinder and Kalmoe2017). The interaction will shed light on this interplay. Second, the interaction term enables us to better control for the (party) identity mechanism by teasing out the independent effect of ideological difference on out-partisan hostility. More concretely, if negative feelings towards out-party supporters are indeed rooted in ideological conflict, then we should find that even for respondents with a weak party identity the effect of ideological difference should still be significant and substantial. Both model 3 and model 8 show that this is the case. When we look at these models, we find a significant interaction effect, demonstrating that the effect of both subjective and objective ideological differences are stronger for respondents with a stronger party identity. This means that the effect of ideology can in part be explained by political group attachment and that the two mechanisms do not work fully independent from one another. Nevertheless, at the same time, we see in model 3 that even for voters that totally do not identify with their in-party (PTV score = 0 and party stability = 0) the thermometer score that a respondent gives to out-party supporters still decreases by 3.5 points for each point that an electorate is perceived to be further away on the subjective ideological distance scale. While this is higher for respondents that fully identify with their party (−3.452+(10 * −0.174)−0.524 = 5.7 points), it is still quite substantial nonetheless. Moreover, in practice this difference is much less outspoken, since even voters that do not really identify with their party still usually give the party they voted for a PTV score of 5. Similar conclusions are reached when we look at objective ideological distance in model 8.

Taken together, these results show that, although party identity does play a role in explaining partisan hostility as well, we are still left with a strong and substantial effect of ideological differences when controlling for this alternative mechanism. This supports our first hypothesis and shows that the higher animus towards supporters of out-parties is indeed to a large extent embedded in the larger ideological distance between these groups, even when taking into account alternative mechanisms.Footnote 5

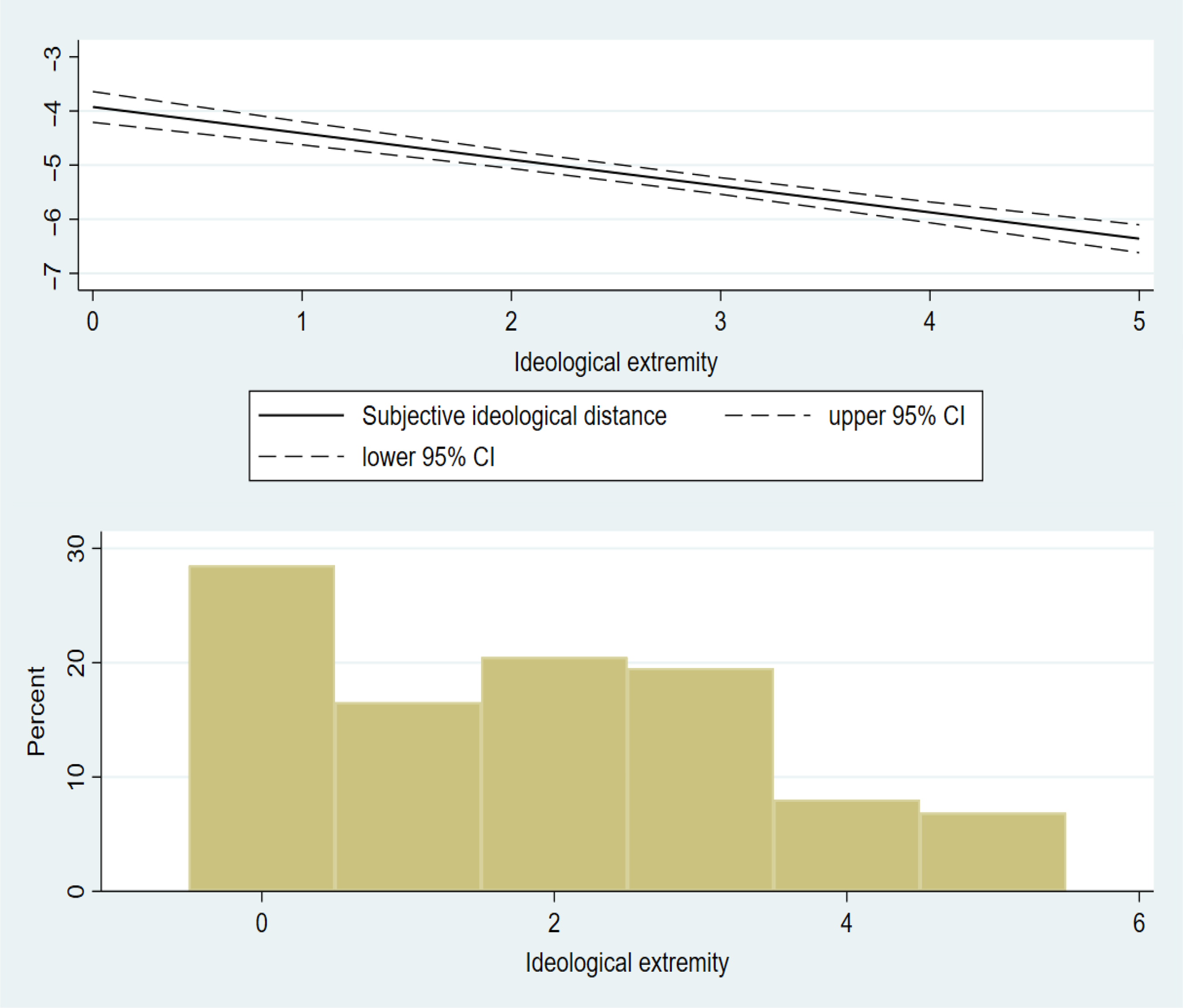

As we argued with the second and third hypotheses, if affective polarization is strongly rooted in ideological conflict then we should additionally find a stronger effect of ideological distance on dislike for citizens who occupy more extreme ideological positions and citizens with high political interest. In model 4 (Table 3) and model 9 (Table 4), we first add interaction terms between, respectively, subjective and objective ideological distances and ideological extremity. Both interactions are significant and show that the effect of ideological distance indeed becomes stronger for those citizens taking a more extreme ideological position. To gauge the strength of this moderation, we plot the interaction with the subjective ideological distance measure from model 4 in Figure 2. The plot shows that whereas for citizens in the centre (scoring 0 on ideological extremity) each additional point of perceived ideological distance results in a drop of 4.0 points in the feeling thermometer scores, this drop moves up to 7.9 points for respondents who take an ideological extreme position (scoring 5 on ideological extremity, which equals 0 or 10 on the left-right scale). Model 9 indicates that this moderation by ideological extremity is even stronger for the objective ideological distance measure.

Figure 2. Interaction between ideological distance and ideological extremity.

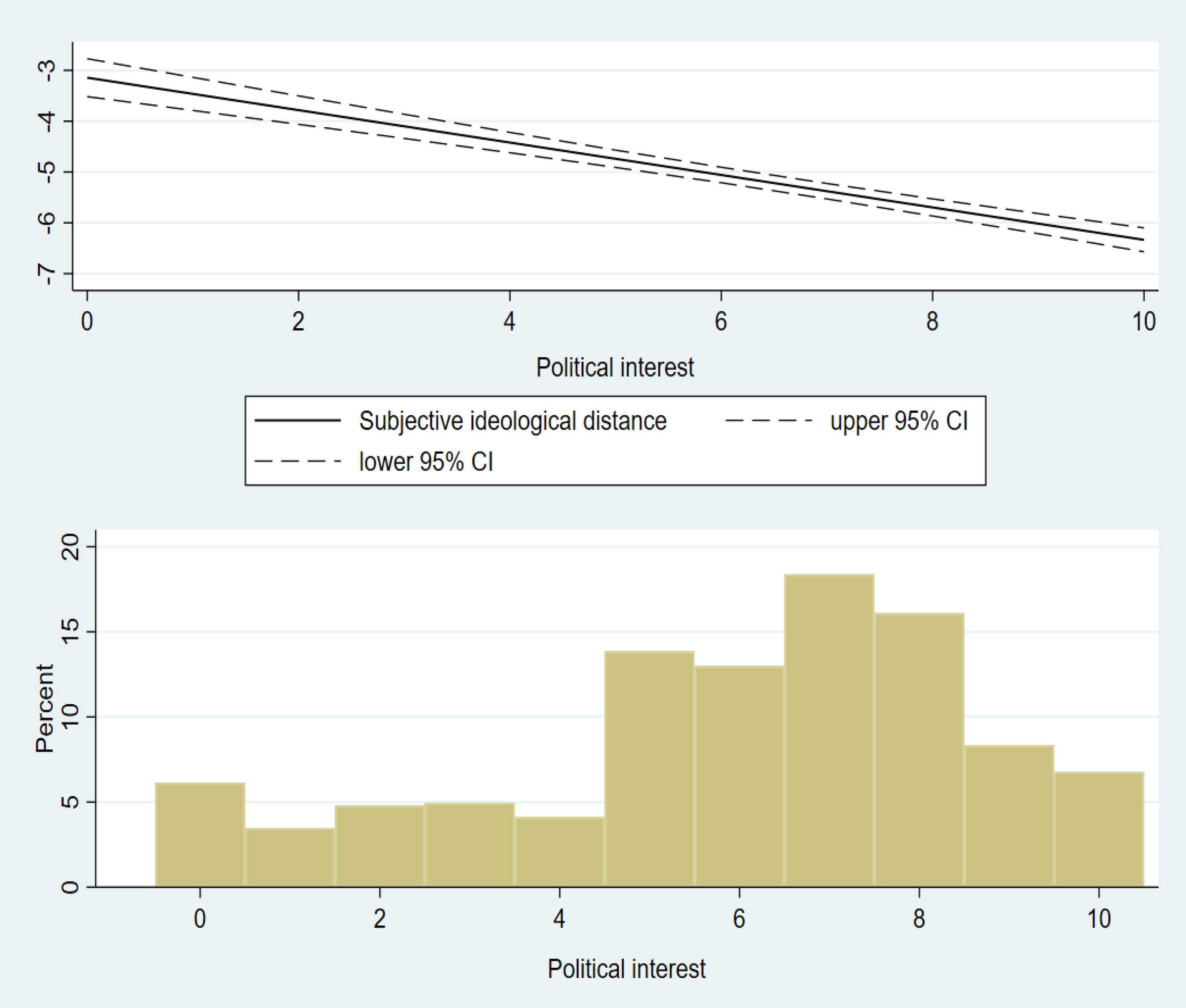

We can perform a similar test for political interest. In model 5 (Table 3) and model 10 (Table 4), we investigate the interaction between, respectively, subjective and objective ideological distances and political interest. In both models, we find that the interaction is significant. Although, even for citizens with low political interest, a larger ideological distance to another partisan group already results in more negative feelings towards that group, we see that this effect becomes stronger when political interest increases. To better gauge the strength of this moderation, we again plot the interaction with the subjective ideological distance measure in Figure 3. The interaction plot shows that for a citizen with no political interest at all, each point that the other partisan group is perceived to be further removed on the ideological score results in a drop of 2.3 points on the feeling thermometer score. For those respondents who have full interest, however, each additional perceived ideological distance point rather results in a decrease of 7.4 points. Moreover, model 10 shows that for the objective ideological distance measure (not plotted), this moderation by political interest is even stronger. This makes sense as the politically interested are more likely to also be aware of these objective ideological distances.

Figure 3. Interaction between ideological distance and political interest.

Altogether, we find support for hypotheses 2 and 3. Although (perceived) ideological distance results in less sympathy for political opponents among all citizens, this effect is stronger for citizens at the ideological extremes and among the politically interested. This is another indication that supports the notion that affective polarization is rooted in ideological differences between groups, at least in this multi-party context.

Conclusion and discussion

There is ubiquitous talk and concern about polarizing societies across the globe. Particularly the trend of affective polarization, where citizens dislike, or even despise, politically other-minded citizens, has researchers worried given the strong negative consequences it can have for democratic societies. Nevertheless, many questions about affective polarization still remain unanswered. This study set out to contribute to one such lingering question, and, utilizing the analytical leverage the fragmented Belgian multi-party system provides, has explored to what extent affective polarization, and more particularly the element of partisan hostility, find its roots in ideological differences. Specifically, we looked into the way out-groups are constructed when there are more than two options, and at the role of ideology in this process. Hereby we position ourselves in the discussion between those who argue that negative feelings towards political opponents, and by extent affective polarization, is more strongly driven by group attachments vs. those who argue that it is more strongly rooted in the ideological differences between different electorates.

Although our findings show that also group attachment, in the form of party identity strength and stability, partly drives partisan hostility, and can even to some extent explain the role of ideology, our results demonstrate that affective polarization is still to a large extent rooted in the ideological differences between different party electorates as well. Citizens become more negative towards out-party electorates as the ideological distance with these electorates increases and this holds both for citizens with strong and weak party identities, although we do see that the effect is a little bit stronger for the first group. These findings hold when using both an objective and a subjective measure of ideological distance. In addition, in line with what we would expect if affective polarization has an ideological basis, we find that this is particularly the case for citizens who are more ideologically invested, namely those with higher political interest and more extreme ideological views. The finding that affective polarization is to a large extent ingrained in ideological differences is somewhat worrying, as it shows that it has a rational basis, making it perhaps more difficult to overcome and to find solutions (Webster and Abramowitz, Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017).

We should acknowledge, however, an important limitation of the present study, namely its measurement of ideology. Despite the subjective and objective operationalization of ideological distance adding sophistication to our measurement, the self-placement on a left–right scale flattens the concept of ideology and does not take into account the multidimensional nature of the Belgian political landscape. Moreover, the answers given to this measurement are somewhat dependent on one’s interpretation of left and right. Respondents may see being ‘left’ or being ‘right’ as part of their political identity as well. Although the fact that we find a strong correlation of our left-right measure with the CHES left-right measure – which reflects a more objective measurement of the ideological position of parties – gives us confidence that we mostly capture the ideological position of the respondents, we cannot fully exclude the possibility that this measure contains an element of ideological identification as well. Future endeavours might thus incorporate a measure of ideology which better captures the more multidimensional character of political ideology (Lesschaeve, Reference Lesschaeve2017; Caughey et al., Reference Caughey, O’Grady and Warshaw2019). Relatedly, the role of consistency between partisan and non-political identity facets (sorting) was not taken into account here. Recent insights into the role of social sorting in spurring affective polarization in multi-party systems point to the importance of considering multiple aspects of identity (Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021b). As such, we encourage further research to delve into the relation between social identities, ideology, and affect.

Another limitation that we should acknowledge is that our results were obtained in one country at one point in time. Although Belgium serves as a representative case for many multi-party systems with similar characteristics, we underline the importance of conducting similar studies in other countries and contexts, as well as more longitudinal investigations. For instance, the fact that in Belgium voters are more volatile – although comparable to many other Western European countries with multi-party systems – and thus have a weaker party identity, could mean that the role of ideology as driver of affective polarization is more prominent than in, for instance, the USA, where party identities are stronger.

Lastly, the present paper has focused on out-group affect. This has enabled us to study the individual scores assigned to the different out-groups without resorting to singular, combined measures in which affect towards all parties are taken together (e.g., Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). Yet, not taking together these scores and not including respondents’ level of in-group affect does come at the cost of a more comparative and relative image of one’s level of polarization, which is a further limitation of this study.

Taken together, the present study provides insights into the manifestation of affective polarization, specifically out-group hostility, in a context with more than two parties. The fact that we find strong ideological roots of negative partisan affect points towards a potential rational basis for intense negative feelings towards supporters of parties that think differently. In the ongoing search for ways to alleviate affective polarization and its effects, it thus seems important to not only focus on how to increase tolerance of and empathy towards other groups, but also on boosting tolerance and legitimacy of other viewpoints.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000121.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge support from the FWO/FNRS Excellence of Science project RepResent (grant number: G0F0218N), the FWO Research Foundation Flanders (grant number: G068417N), and from the KU Leuven (grant number: C14/17/022). Furthermore, the authors extend their gratitude to the University of Antwerp research group Media, Movements, and Politics (M2P), KU Leuven’s Democratic Innovations and Legitimacy Research Group, and Eelco Harteveld for their insightful comments and helpful feedback.