For this issue of NBC, we investigate a range of different approaches to the archaeology of ritual. The attribution of unexplained phenomena to ritual practice is something of a cliché in public perceptions of archaeology (just try googling ‘ritual archaeology cartoon’!), and even within the discipline there are those who remain sceptical that we can ascend Hawkes's ladder of inference (1954) to such dizzy heights. Yet several recent books coming in to the Antiquity office show how both theory and method are advancing our understanding of this complex concept. Sparked by the publication of two major volumes from Cambridge, we here take the pulse of the archaeology of ritual, and find it in rude health.

On ritual

Renfrew, Colin, Morley, Iain & Boyd, Michael (ed.). 2018. Ritual, play and belief, in evolution and early human societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 978-1-10714-356-2 £90.

Renfrew, Colin, Boyd, Michael J. & Morley, Iain (ed.). 2016. Death rituals, social order and the archaeology of immortality in the ancient world. New York: Cambridge University Press; 978-1-107-08273-1 £75.

Livarda, Alexandra, Madgwick, Richard & Mora, Santiago Riera (ed.). 2017. The bioarchaeology of ritual and religion. Oxford: Oxbow; 978-1-78570-828-2 £45.

Bergsvik, Knut & Dowd, Marion (ed.). 2018. Caves and ritual in medieval Europe, AD 500–1500. Oxford: Oxbow; 978-1-78570-832-9 £50.

Our first two volumes, both edited by Colin Renfrew, Michael J. Boyd and Iain Morley, come out of a major project funded by the John Templeton Foundation, entitled ‘Becoming Human: The Emergence of Meaning’. As the title suggests, the intellectual scope of the project goes well beyond archaeology, and the two symposia on which these books are based included scholars from a wide range of disciplines. The unifying theme of both, beyond ritual, is a commitment to the cognitive archaeological approach, which holds that material remains can be used to reconstruct the broad forms of belief within ancient societies, even if precise symbolic meanings remain elusive (Renfrew Reference Renfrew, Renfrew and Zubrow1994).

We will start with the topic that is perhaps less familiar to archaeologists. Ritual, play and belief, in evolution and early human societies brings the idea of play into the study of ritual and spirituality. Linking play and ritual together may seem somewhat left field, but, as Renfrew argues in a cogent Introduction (one of two, the other by Morley), they can be linked by the fact that neither is “devoted to immediately functional purposes” (p.13), and both have performative aspects. In the first section of the book, ‘Play and ritual: forms foundations and evolution in animals and man’, two biologists (Burghardt and Bateson), a psychologist (Smith) and two anthropologists (Morley and Dissanayake) set out why this link is important. Essentially, as play behaviours have been observed in many species of animals (and birds), but rituals are generally considered to be a distinctly human phenomenon, we can think of the former as an evolutionary precursor to the latter. Thinking about ritual in relation to play, then, becomes a useful heuristic tool in interpreting the archaeological record.

This is the aim of parts II and III of the book, where a series of case studies relating to different societies and their approaches to ritual, play and performance are presented. In part II, ‘Playing with belief and performance in ancient societies’, the focus is on the performative aspect of ritual. The geographic scope is impressive, moving from the Maya in Central America (Freidel and Rich), the North American Southwest (Halley), the Near East (Watkins, Garfinkel), China (Sterckx) and Malta (Malone). The importance of communal performative activities in the construction of group identity comes through well in each chapter. I particularly enjoyed Yosef Garfinkel's discussion of the use of masks and dancing rituals in the pre- and proto-historic Near East, as well as Sterckx's detailed chapter, heavily dependent on textual sources, on the perceptions of ritual and play in humans and animals in early imperial China. Part III, ‘The ritual in the game, the game in the ritual’, turns towards a specific form of play, the game, defined by Spivey in his chapter as “a voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles” (p. 253). Such a definition blurs the lines between rituals and games, and many of the chapters bear this out. Those by Morgan, Marinatos, and Spivey all focus on ancient Greece, where games based on hunting, bull-leaping and even combat were common and often performed in sacred spaces such as sanctuaries. Taube shows in his discussion of the famous Maya ball game that the entertainment aspect of the spectacle was intimately connected to rituals related to rainfall and fertility. Reading this section, I was struck by some of the parallels visible with our own rapidly secularising society, where sport can be bound up in ritualised practice related to performance and community belonging, from local group affiliations to national identities. As the legendary Liverpool manager Bill Shankley once said of football, ‘some people believe (it) is a matter of life and death [...] I can assure you it is much, much more important than that’!

Unusually for an edited volume, we end with not one but three conclusions, written by scholars invited as discussants to the original conference. This works very well as each demonstrates a thorough engagement with the preceding body of work as well as providing particular insights from the authors’ own ideas. Thus, Malafouris emphasises the role of material culture, and especially toys, in the development of both play and ritual, while Osborne makes a persuasive attempt at a separation of ritual, play and more quotidian activities. For Osborne, ritual and play share the quality of being not-normal, outside the realm of everyday life, but differ in that ritual is goal-oriented, whereas play, almost by definition, is aimless. Morley develops this theme into a small-scale model, based around the memorably named ‘pentagram of performance’. Overall, this is an extremely useful intervention in archaeological studies of both ritual and play. Even if one is not convinced, by the end, of a clear evolutionary link between the two, there can be little doubt that an intellectual one is proving very productive.

The second Cambridge book, Death rituals, social order and the archaeology of immortality in the ancient world, returns us to the (archaeologically) more familiar territory of death and mortuary remains. Renfrew provides another cogent introduction, although there are some discrepancies between the structure of the book as he describes it and the actual chapter groupings. He lays out the aim of the volume: to take a fresh look at the different ways that humans have dealt with death, and from there to try to get at how they may have conceived of it. References to cognitive archaeology are here more explicit. The following 26 chapters are written by a veritable smorgasbord of high-powered scholars, covering every inhabited continent and moving from the Middle Palaeolithic to Historic periods. These are organised thematically and, because the themes relate to increasing levels of complexity, loosely chronologically.

The first section deals with the period before farming, beginning with a discussion of the concept of death in modern animal species by biologists Piel and Stewart. Hyper social, large-brained animals such as elephants, dolphins and chimpanzees react to the dead bodies of their species in recognisable ways, suggesting a possible evolutionary trajectory towards modern humans. The next two chapters develop this theme using archaeological evidence to discuss concepts of death in the Lower and Middle (Zilhão) and Upper (d'Errico and Vanhaeren) Palaeolithic. Both treat this much debated subject with an impressive even-handedness, drawing on the latest archaeological discoveries. Together they support a gradual trajectory for the emergence of mortuary behaviour, beginning at least in the Middle Palaeolithic and significantly including Neanderthals and even perhaps earlier hominins, as opposed to the idea of a step change as a result of new cognitive abilities present in Homo sapiens. The second section moves us to the Neolithic, with several chapters examining the role of the dead in early sedentary societies. From Gobekli Tepe in Turkey (again) to Britain, via Jordan, Peru and Malta, we see how mortuary remains become embedded in delineations of territory and community as human groups began to live in larger numbers for longer periods. This theme is developed in section three, on the role of ancestors. Here, chapters by Snodgrass and Boyd, both dealing with the Greek mainland, are particularly interesting. Drawing on anthropological work and material evidence, they argue that the veneration of ancestors is a specific set of behaviours that has been generalised too widely in the archaeological community, but importantly, that it can be recognised in the material record. Section four deals with state-level societies, passing through the Royal Cemetery at Ur, elite burials among the Maya, Japan and Southeast Asia. In this section, I found Mizoguchi's (somewhat confusingly titled) account of the role of elite burials in early state formation in Japan the most stimulating. Elites were buried in massive key-hole shaped tumuli, some over 250m in length, the construction of which Mizoguchi argues re-enacted the birth of the world and brought together various sections of society into fictive kinship groups. In a very real sense, then, the absence brought about by death forged just the sort of imagined community we associate with states.

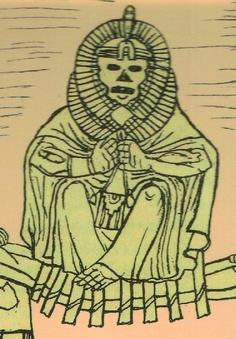

The penultimate section is the least coherent. Creese's paper on the Iroquois might have been a better fit in the section on ancestors, as seems to have been intended when Renfrew wrote his Introduction! Each of the chapters, however, generally considers the role of belief systems in state-level societies, including Buddhist India, Egypt and the Inka. D'Altroy shows how the complex, sun-based cosmology of the Inkas, so alien to the Spanish conquistadors who first encountered it, gave sufficient ‘life’ to the mummified bodies of elites that their destruction could be considered a second death. Citing the rapidity with which this belief system fell apart after the conquest, he argues that it was intimately bound up with institutions and ideologies of power supporting the Inka elites. The final section provides a pleasingly multivocal and informal set of conclusions. Wason's is perhaps the most conventional, drawing out major themes and future directions from the volume as a whole in a helpful bullet point format. Anthropologist Timothy Jenkins uses Durkheim to think about the way that archaeologists and anthropologists deal with comparison and complexity, both in relation to mortuary remains and more generally. Finally, the poet and novelist Ben Okri offers a non-academic perspective, reflecting on what it means to take an analytical approach to a concept as profound as death, and reminding us of the essential wonder that archaeology's material connections can invoke.

The intellectual coherence of these two volumes, particularly given the vast spatial and temporal span of the chapters, is impressive, and reflects the overarching topics chosen for each, the calibre of the scholarship and the nature of the meetings that brought them about. The latter were long affairs by today's standards—four days in the case of the death symposium—and evidently allowed for a great deal of productive discussion alongside individual papers. The inclusion of academics from outside archaeology clearly enhanced these discussions and resulted in much more thought-provoking books as a result. In archaeology, and indeed academia in general in much of the world, this kind of time and space is a luxury, and opportunities for residential symposia are relatively rare. Both of these books demonstrate just how productive they can be.

Our third book, The bioarchaeology of ritual and religion, is another collected volume, this time based on an EAA session at Istanbul in 2014. The main aim of the session was to “showcase new research on ritual and religion relating directly to perishable material culture, with the bioarchaeological disciplines other than osteoarchaeology, being at the centre of the research” (from the Preface). In a well-written and detailed Introduction, the three editors situate the volume firmly within what we might call the social turn in recent bioarchaeological research, with several articles published in the last decade calling for a deeper engagement with theory and, as a result, with major archaeological questions. Here, this results in a particular attendance to the processes and performative aspects of rituals, rather than the scientific study of the remains as they are presented in the archaeological record. The editors also use the Introduction to justify their decision not to invite osteoarchaeology to the party. They argue, rightly, that the bioarchaeological study of ritual has been dominated by analyses of death and the afterlife, meaning osteoarchaeology has dominated debates at the expense of other sub-disciplines. The second aim of the volume is to begin to right this wrong.

Somewhat gratifyingly, after the uneven divisions provided by the Renfrew volumes, the following 13 chapters are not parcelled out into subtitled sections. There are, however, rough groups based on scientific approach, moving from micromorphology through plant remains to animal bones (by far the largest group). Geographically we stay within Europe, as one might expect from an EAA session, with the UK, Italy and Spain dominating, and cameo appearances from Switzerland, Greece and Estonia. The chronological range is wide, beginning in the Mesolithic and ending in the medieval period, although again there are clusters of chapters in certain areas, notably the Iron Age and Roman period. I will not attempt to summarise each chapter, but rather discuss a few choice cuts that provide a flavour of the whole.

At High Pasture Cave on the Isle of Skye, McKenzie uses micromorphology to investigate potential ritual activities during the Iron Age. Faunal and botanical samples from the excavations revealed highly unusual assemblages, including a huge number of pig bones and large caches of barley. McKenzie adds to this by recovering evidence for major ritual burning events at the centre of the cave, as well as elevated phosphates, which she interprets as evidence for bloodletting and butchery. Riera Mora et al. examine a set of Late Bronze Age human remains from the cave site of Cova des Pas in Minorca. Using detailed sampling and pollen analysis, they are able to reconstruct an entire ritual sequence, with different species of flowers placed inside, and outside of, the shroud, alongside fruit offerings. Several chapters take advantage of the relative comparability of bioarchaeological datasets to assess ritual practice through time and space. Brettell et al. combine textual sources and plant residue analysis to identify “the limited palette of substance deemed appropriate for the mortuary sphere” (p. 53) in Roman Britain, and show how these were used to hide the decomposition of the body. A comparative analysis of faunal assemblages from cave sites in Bronze Age Italy allow Silvestri et al. to demonstrate the wide variety of animals with potentially symbolic properties, including hares, piglets, stags and dogs. By contrast, Best and Mulville make a convincing case for the specific symbolic importance of white-tailed eagles in mortuary practices of the Scottish islands, beginning in the Mesolithic and continuing into the Bronze Age.

After the excellent introductory chapter had developed a theoretical position, and given the wide variety of individual content chapters, each data-rich and engaging with the brief, I was expecting a conclusion that would draw some of the threads of the volume together. Unfortunately, such a conclusion is not provided. Instead, the final chapter is a rather anomalous essay by Brian Hayden on secret societies, which, although interesting, seems to have very little to do with bioarchaeology and is only loosely tied to ritual. This is a shame as the rest of the chapters stick to the premise well, demonstrating what close attention to taphonomy and context in combination with the latest scientific techniques can add to an understanding of past ritual practices.

We round off this issue's NBC with Caves and ritual in medieval Europe, AD 500–1500. The volume is edited by two prehistorians, who noted in their own research on prehistoric cave sites that the substantial medieval deposits they came across were not discussed by medieval archaeologists. The editors attribute this to two factors: firstly, the frequent disturbance of the upper levels in many cave contexts, precluding detailed contextual study of the most recent remains; and secondly, the architectural and art historical focus of much medieval archaeology, which pushes attention away from cave sites. We might also add the tendency for prehistorians to skip over evidence for later uses of caves and a consequent reluctance to publish such remains in full. Luckily, the editors are not from this school and instead decided to engage with the topic in its own right. One EAA session later and we now have 17 case-study chapters covering the whole of Europe, and, despite the book's title, discussing periods from the pre-Roman to the early modern. The majority of the chapters do focus squarely on Christian, or Christianising, Europe, and it is therefore interesting to think about ritual and religious practice during a period in which we know quite a lot about the actual beliefs of the practitioners, or at least think we do.

A strong emergent theme is the way that Christianity transformed cave use, both in the ways in which it interacted with, and often co-opted, ‘pagan’ belief systems, and through new ideas of ascetic contemplation that resulted in an explosion of eremitism and monasticism at cave sites. In some cases, the use of caves as sites of ritual practice reflects much longer traditions. Buster and Armit link Pictish symbols, dated to between 400 and 900 AD, and carved into the Sculptor's Cave site in north-east Scotland, to the long history of mortuary practice at the site, which goes back to the Late Bronze Age. They argue that the cave may have been perceived as a gateway to the underworld and that some of the symbols were designed to Christianise a pagan holy place. In Malta, Late Antique sanctuaries became Christian burial sites. Such relationships have been posited for many Early Christian holy sites, but several chapters downplay this interpretation, noting the absence of material evidence for pre-Christian rituals (for example, Dowd in Ireland, Schulze-Dörrlamm in Germany). More dramatically, Prijatelli shows how Christian attitudes to caves changed over time in Slovenia, and that intolerance of ‘pagan’ ritual practices may have led to the deliberate closure of cave complexes by Christian authorities. The striking thing about the papers presented here is the sheer diversity of ritual and religious practice that was going on in cave sites over the two millennia investigated. By bringing this to light, the editors, and authors, should certainly succeed in their aim to start a conversation on the uses of caves during the medieval period. Again, however, it would have been useful to direct these discussions by including some final thoughts to pull together the emergent themes from the mass of data presented. It seems that conclusions in books on ritual, like buses, are absent until three come along at once.

The volumes presented here point to a range of future trajectories for the archaeology of ritual. The rich theoretical depth, substantial engagement with other disciplines and detailed archaeological knowledge visible in the Renfrew-edited collections show how comparative cognitive archaeology can generate concrete steps forward. It is refreshing to see archaeologists leading projects of such ambition, tackling really big questions. At the same time, The bioarchaeology of ritual and religion demonstrates the immense capacity of archaeological science to add to our understanding of the material remains that we recover. One only has to think of the suite of techniques that could have been applied to the Royal Cemetery at Ur if it were excavated today to see the potential here—although admittedly it would take several hundred years to uncover Wooley's trenches in full if modern sampling protocols were followed. Finally, Caves and ritual reminds us that there are still large areas of the world, even in developed nations and during periods that we consider well evidenced, where very few sites of particular kinds have received any attention at all. We must hope that the future excavators of such places manage to combine deep theoretical engagement with cutting-edge scientific techniques.