Introduction

Preparing for his imminent immigration to the United States, Heinz Bähr (later Henry Bahr) returned to his hometown of Breisach am Rhein in 1937, photographing his extended family and members of the small provincial Jewish community. Donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the selection of farewell photos – a little over twenty in total – consists of portraits of individuals and photos of the local Jewish community inside and outside the local synagogue on a Saturday morning. As we will see, these photographs suggest resilience and self-confidence, themes that have become commonplace in the history of Jewish resistance to National Socialism. The photographs reveal, moreover, a community composed overwhelmingly of elderly individuals who appear to have been aware of the unique historical moment in which they lived. Yet, the images also remind us of how postmemory and the tendency to implicitly read the anterior future into photographs from the 1930s can colour our understanding of these photos. As Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer have noted, postmemory influences many aspects of memory formation. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's specific Holocaust narrative, as they note, is predicated on our retrospective knowledge of that which had not yet come to pass.Footnote 1 After all, neither Bähr nor those who stood in front of his camera did or could foresee the genocide that the National Socialists and their collaborators would begin only several years later. They had, by this point, witnessed persecution and arrests (more on this shortly) but, as I argue in the following pages, we must be careful to assess these images based on the imaginative horizons that were conceivable to those living at the precise time that the photos were taken. This article will thus address the drive to record individuals and the local Jewish community as they emerged from time-specific and very personal considerations as well as from an awareness of the significance of their own historical experience up until that time: namely, the community's clear decline as the pace of out-migration – already a phenomenon common to rural and provincial Jewish communities before 1933 – further accelerated as a consequence of persecution. It was in this specific context that many individuals involved in the production of the images, including Bähr and the various members of the local Jewish community in Breisach, appear to have been intent on recording what remained.

On a basic level, this article seeks, first, to offer insights into the experiences of two historiographically underrepresented – but in this specific case overlapping – groups during the National Socialist era: the elderly (especially elderly Jews) and Jews who lived in provincial towns.Footnote 2 It is well known that the elderly were particularly vulnerable under the National Socialist regime. As I will discuss in greater detail below, the older an individual was, generally the harder it was for him/her to immigrate. This led to a demographic, and gendered, imbalance: a disproportionate number of elderly people remained in Nazi Germany while many of their younger (especially male) family members were able to flee the country. However, to date, there is still very little research that explores the experience of many elderly German Jews who were unable to leave National Socialist Germany and perished during the Holocaust. Secondly, as I demonstrate, photography was not simply a means to represent the elderly through the eyes of younger Jews but, far more importantly, was an intergenerational practice of constituting communal memory. Through the example of the Bähr collection, we can see and analyse the self-perceptions of those who stood in front of and behind the camera as well as how these actors chose to represent historical processes on film and, in so doing, participate in the construction of the memory of individuals and the community to which they belonged.

This article furthermore explores the case of a provincial Jewish community as it recorded its own history during a period of intense urbanisation, emigration and flight. Much of the primary source material we have concerning the modern German–Jewish experience, including photographic sources, comes from Jews who lived in medium to large cities. The Bähr collection is thus exceptional for the underrepresented perspectives and momentous historical processes that are simultaneously reflected in the photographs. Through an analysis of the photographs Heinz Bähr took while visiting his childhood home of Breisach, this article demonstrates how Breisach's Jewish community, and in particular its elderly residents, sought to participate as individuals and as a community in the creation of memory, both visually and materially, recording their experiences. The images of the elderly in no way presented the subjects as mere ‘objects’ of the photographer's gaze. The photographs reveal conscious attempts both on the part of the photographer and the photographed to assert the enduring presence and personal relevance of those seen in the various images, their desire to be seen and remembered by a future viewer, and to create reproducible material artefacts to enable the dissemination of these claims for perpetuity. The photos also display a keen awareness of the historical uniqueness of the era and its significance, with the photographs highlighting the clear changes that the Jewish community of Breisach had experienced both over the course of the early twentieth century and then more drastically during the National Socialist era. To be sure, the photographs serve as an excellent example of cultural and spiritual resistance as the community consciously chose to stress its continued dedication to Jewish religious practice. Yet, we must remember the limits of their own knowledge. If they were aware of the historical significance of their era, it was not because of what was going to happen, but because of what had already, by late 1937, happened.

Already before the rise of National Socialism, the camera had become a popular tool for recording events, people and places for posterity, and Jewish individuals as well as Jewish communities were keen to take advantage of this new technology to similar ends.Footnote 3 With the National Socialist rise to power in early 1933, the desire to document and commemorate Jewish life gained new urgency and distinct rationales, and the photographic record offers a highly diverse reaction to the increased persecution German Jews faced under the National Socialist regime, attesting to the desire of many to push back against their marginalisation and reassert their belonging to society and the local landscape.Footnote 4 And, in many respects, it was photography's purportedly ‘indexical’ quality – namely, as it is understood within the history of photography, its ability to seemingly reflect that which really was – that privileged its use in memory creation and inspired attempts to create historical records.Footnote 5 Indeed, photography's ‘indexical promise’ itself appears to have been a contributing factor behind the decision to allow Bähr to take photos on Saturday, otherwise a time when taking photos would have been prohibited by religious law.Footnote 6

Nonetheless, as we will see throughout this paper, the assumption that photography is a ‘transparent medium’ has meant, as Hilde van Gelder and Helen Westgeest and others have rightly pointed out, that ‘one forgets one is looking at a mediated reality instead of reality itself’.Footnote 7 For as much as photography can depict its referent with remarkable precision, it nonetheless remains a form of representation. Even snapshots, as Brian Wallis has explained in the context of ‘vernacular’ photographyFootnote 8 more generally, ‘serve as vehicles for subjects, and viewers, to assert or investigate issues of personal identity, family affiliation, gender identification, class status, national affinity, or community membership – sometimes in conformity with societal norms but often pushing firmly against them’.Footnote 9

Yet, the current consensus on photography as a representational medium does not merely reflect an extension of the sociological approach to photography, which takes the latter to be a revelatory tool for understanding habitus and everyday visual conventions.Footnote 10 Instead, it is predicated upon a three-way relationship between the photographer, the person photographed, and the viewer. This Barthian understanding of photography makes room for an additional participant: the viewer who is invited to consider and find meaning(s) in the images and in the way they are represented, to read them as ‘communicative acts’.Footnote 11

One of the most common of these communicative acts is that of memory creation. Family photos, for example, are acts of ‘preemptive commemoration’: ‘Their purpose is to represent the moment: not just for immediate consumption, but also as it is to be remembered in the future, and by future generations’.Footnote 12 To be sure, the highly realistic nature of the photographed image has only helped to privilege its use in the process of memory formation and commemoration, with the added benefit that the photograph is itself a material possession that can be held, transported and viewed repeatedly.Footnote 13

At the same time, a photograph is not the person, but a trace of them, and the photo's relationship to memory is contested and contestable, since the two are not identical.Footnote 14 This renders viewing photographs not only an act of remembering, or even creating memory, but an act of identification and empathy. Barthes's famous search for a photo of his deceased mother that could reveal her essence is emblematic of the belief that not all photos represent their subject in such a way as to elicit an emotional response from their viewer. Instead, his quest for ‘the truth of the face that I had loved’ required that he as the viewer be able to identify with the photograph and be touched, even ‘wounded’, by a specific aspect of it.Footnote 15 While we might argue that Barthes himself was falling victim to some form of indexical fallacy in that he assumed that a photo could and did reveal something that was truly there, we cannot help but acknowledge that for most vernacular photographers, the assumption that photographs reflect and reveal something ‘true’ about a family member, friend or loved one undergirds the very logic of vernacular photography and compiling photo albums.

The viewer's act of looking at and re-viewing photographs makes them a participant in a process of meaning-creation that is continually (re-)created through each subsequent viewing.Footnote 16 Although the photographed subject cannot return the viewer's gaze – thereby precluding, in Levinas's reading, the possibility of the creation of a sense of responsibility between the viewer and the viewed – I would argue that Bähr's collection of farewell photographs reveals an attempt to express responsibility for the legacy of his nuclear and extended family as well as that of his community.Footnote 17

Yet, before we begin with an analysis of Heinz Bähr's small collection, we must first explore how it came to pass that the Jewish community of Breisach was, by the time Bähr visited in 1937, disproportionally composed of elderly individuals. What sociological and political circumstances led to such a situation? What did it mean to be elderly at the time? And how was the category of the ‘elderly’ even defined?

The Challenges and Dire Consequences of Defining ‘Old Age’

There is no universal definition for the ‘elderly’, no magic number that marks the passage into ‘old age’. Instead, the terms ‘elderly’ and ‘old’, far from reflecting a neutral, objective assessment based on chronological age, are subject to significant degrees of negotiation and are highly contested. They also have numerous value judgements attached to them, and these stereotypes and (mis)perceptions about chronological age, in general, can be used and abused by political apparatuses to bestow rights and responsibilities upon some groups while withholding them from others. From this perspective, several scholars have recently suggested that we see chronological age not as a simple biological fact but as a vector of power.Footnote 18

One of the most important markers then of the passage into ‘old age’ has been and still is the association of being ‘elderly’ with the inability to carry out ‘productive’ labour. In many societies today this distinction has, or at least can have, significant socio-economic repercussions, including discrimination in the workplace as older individuals are perceived as being less efficient and thus less desirable employees, discrimination that can even result in poverty.Footnote 19 For as much as these considerations have possibly negative outcomes for the elderly today, in National Socialist Germany they would have murderous consequences. As Katharina von Kellenbach notes, ‘senior citizens were especially vulnerable. They were unable to secure their survival by proving their worth as workers and by “organising” the necessities of life. They were perceived as a drain on shrinking economic resources and as a burden on the community’.Footnote 20 To give a sense of what was at stake as a result of these subjective understandings of age, it is worth considering select fragments of the discourse on professional training and retraining that took place among German Jews in the late 1930s.

Faced with increasing numbers of unemployed and the growing realisation that immigration would be the only sure way of securing one's material existence and finding safety, various Jewish institutions and organisations established, funded and ran programmes with the goal of helping to educate and retrain prospective Jewish emigrants.Footnote 21 Individuals, too, set about trying to find new professional opportunities. Marion A. Kaplan has noted that, up until 1937, for example, the Central Bureau for Economic Relief (Zentralstelle für jüdische Wirtschaftshilfe) helped roughly 20,000 individuals to finance professional training. Hachshara camps and programmes, too, were vital for preparing young Jews for work in agriculture and manual trades in Mandatory Palestine.Footnote 22 Yet, age and gender would play significant roles in determining who would be trained, what kind of training they would receive and what form or degree of support they would receive as they tried to emigrate from National Socialist Germany.

First, we should note that already before the rise of the National Socialists to power in 1933, German Jews were, on the whole, older than the non-Jewish population, and there were more Jewish women than men.Footnote 23 On top of this, however, there were additional important gender-based considerations that helped some individuals emigrate while hindering others. For instance, there were fewer training options for young women than there were for men; as Marion Kaplan has noted, boys were given ‘preferential treatment’ and were offered more choices for training and more subsidies to learn. As well, there was a clear reticence to encourage young, single women to emigrate alone, though the same logic was not applied to young, single men. Moreover, after Pogrom Night in 1938 and the arrest of many Jewish men, many families and organisations decided to prioritise helping Jewish men flee Germany, wrongly assuming that women were safer. Finally, many other women chose to stay behind to take care of ageing family members.Footnote 24 Together, this meant that by the end of the 1930s there was a significant demographic imbalance within the German-Jewish population with far more women, especially elderly women, still living on German soil. Jonathan Zatlin notes that by November 1941, the proportion of Jewish women had increased to 59.14 per cent of the entire Jewish population. Furthermore, by June 1942 the proportion of Jewish individuals above the age of 65 still living in Germany was approximately 35 per cent of the total Jewish population (though this was in part because the deportations of younger Jews had already begun).Footnote 25

None of this is to suggest, however, that it was easy for Jewish men to leave. The older a man was, the harder it was for him to find ways to flee Germany. In an article published in Jewish Social Studies in 1939, the author Rudolph Stahl explained the challenges that were entailed in the process of professional retraining, especially training that involved a clear decline in social prestige, making the process harder not only technically but psychologically as well:

Preparation for a manual vocation involves not only the acquisition of a certain amount of technical knowledge but also means a completely new mode of life for most of the pupils. The merchant who formerly sold his wares or kept his books, or the lawyer who formerly pleaded before the bar, belonged to a respected social class with its definite scale of values and judgments. The academician and professional ranked higher than the merchant, and the industrialist higher than the store-keeper. This social position did not necessarily always carry with it a greater financial income but it usually brought with it greater esteem from friends and the outside world.Footnote 26

The overwhelmingly middle-class professions, which German Jews had practised until the rise of the National Socialists to power, were now largely barred to them, and finding a job in the same profession abroad was particularly difficult considering language barriers as well as a frequent lack of networks and contacts. Most of the new jobs for which these would-be immigrants now trained were not socio-economically better ones; retraining often implied socio-economic decline and, in general, led to the de-embourgeoisement of a once overwhelmingly middle-class social group. Stahl, who had been responsible for professional retraining in Frankfurt am Main sometime before the publication of the article, argued that precisely because of these psychological challenges there was a natural age limit for ‘occupational retraining’. He wrote:

Experience has shown that individuals of more than about twenty-eight years of age [!] do not in general possess the capacity to adjust themselves either physically or psychically to new manual occupations. Even when physical difficulties are overcome, the intellectual and psychic attitudes of an older person usually prevent him from being able to remain true to his new calling in critical situations, and not to attempt to stray back to his old vocation.Footnote 27

He adds that a full 85 per cent of those being ‘retrained’ were under the age of twenty-six.Footnote 28 There is thus a good chance that many of those under the age of twenty-six were not being retrained but were learning a vocation for the very first time. Stahl's assessment is quite extreme, and there appears to be a self-fulfilling prophecy that undergirds his assessment. If most of those in (re)training programmes were young to begin with, then there is a good chance that this reality had in part to do with precisely the same negative perceptions about the very possibility of older adults, even those in their thirties, being able to adjust to new professional circumstances. In other words, the young were assumed to be more suitable for such training and thus received it.

Although Stahl appears to have been harsh in his assessment, he was certainly not the only one to discuss the challenges that conceptions about age posed for professional retraining. Erich Salinger somewhat more optimistically wrote for the Jüdische Wohlfahrtspflege und Sozialpolitik in 1938 that individuals between the ages of fifty and sixty could, at least theoretically, transition into new professions, but there were caveats: certain jobs were simply too physically demanding for those above fifty and the process would in any event not be easy and was possible only under certain circumstances. He advised that ideally one should seek a position that builds upon existing knowledge. A doctor, for example, could work in a laboratory, or as a physical therapist; a dentist could work as a dental technician.Footnote 29

The debate before the Second World War about the point at which one was considered ‘too old’ therefore revolved not only around the issue of one's ability to carry out work that was typically more physical in nature, but around the perception of a person's ability to adapt to new circumstances and new jobs. Teenagers and young adults were not only seen as being stronger and healthier, and thus more suited to physical labour, but also as being more psychologically flexible and resilient. Together, these considerations meant in practice that Jewish organisations both in Germany and abroad focused retraining and education programmes on the young (especially on young men), and allocated funding to other programs, like retirement homes, for the elderly.Footnote 30

To be sure, German Jews were acting not simply on the basis of their own preconceptions about age; similar age-based calculations were shared by the governments of countries to which Jews sought to emigrate and flee. From both within Jewish communities and from the perspective of governments around the world, the older one was the less ‘suitable’ and thus desirable one became as a potential immigrant. This would have dire consequences, since, especially as antisemitic persecution turned genocidal, the perceived ability to do manual labour was frequently the difference between immediate extermination and the possibility of surviving, albeit under inhumane and brutal conditions, another day.Footnote 31 Given this sinister calculus, historian Dan Stone has chosen to define the ‘elderly’ as anyone over the age of fifty-five (quite young in other contexts), precisely because anyone above that age ‘who survived the Holocaust was exceptional’.Footnote 32 The fact that so many elderly Jews perished also has consequences for historians since we are deprived of both a comparable volume and also many types of sources that younger Jews who either fled Germany or survived the Holocaust were able to record and deposit in archives or with family members (e.g., written memoirs). The violent dispossession and murder of so many German Jews above the age of fifty-five have created a fragmented historical record. From this perspective, Bähr's collection gains greater import.

Leaving Breisach: Self-Representation, Resistance and Memorialisation

Heinz Bähr's departure from Breisach reproduced the young, often male story of migration and flight from National Socialist Germany. To be sure, rural and provincial Jewish communities had already begun to experience a gradual demographic decline. The number of Jews living in Breisach peaked in absolute terms in 1880 when there was a total Jewish population of 564 individuals. From then on, the numbers steadily declined as younger Jews took advantage of professional opportunities in larger towns and cities. This demographic shift also coincided with the decline of its relative position in regional Jewish life: Breisach had been home to the district rabbinate until 1885 when it was moved to nearby Freiburg. By 1933 there were only 231 Jews remaining.Footnote 33 Throughout the nineteenth century, the Jewish community had accounted for a sizeable proportion of Breisach's population – accounting for slightly more than 16 per cent, many of whom made their living through trade (e.g., textiles, grain, and household goods), or owned small shops or pubs and restaurants.Footnote 34

Heinz Bähr's family had deep roots in Breisach and enjoyed a degree of standing within the community; his uncle, Hermann Bähr, served as the last parnass (a secular leader) of the Jewish community in the town. Yet, it was clear that Heinz too, like other younger Jews, had set his sights beyond the small town, even before the rise of the National Socialists. He chose to attend university and received a doctorate in law from the nearby University of Freiburg in 1933.

Despite what were described as friendly relations between Jews and their non-Jewish neighbours prior to the rise of the National Socialists, the town's Jews faced antisemitic persecution already in early 1933. On the evening of 31 March 1933 (i.e., the eve of the nationwide anti-Jewish boycott), a number of Jews returning from work in nearby Freiburg were arbitrarily arrested, held overnight and in some cases beaten. These arrests and violence apparently triggered a new wave of migration out of Breisach.Footnote 35

For his part, Heinz Bähr was unable to continue practising law after the National Socialist government passed the law excluding Jews from the civil service in September 1933 and he decided to move to Paris in 1934, where he opened a branch of his father's and uncle's business.Footnote 36 He succeeded in obtaining an immigration visa to the United States and was just shy of his twenty-eighth birthday when he returned to Breisach in 1937 for a final visit. During this time, he photographed his immediate and extended family, and members of the local Jewish community, roughly only more than a year before the local synagogue would be destroyed during Pogrom Night in November 1938.Footnote 37

Although Heinz would emigrate – like 149 other Jews who were still living in Breisach in 1933 – his parents (Julius and Natalie ‘Talie’ Bähr) along with his uncle and aunt (Hermann and Fanny Bähr) and one of his two cousins, Ruth, remained.Footnote 38 Heinz's other cousin, Margot, succeeded in fleeing to the Netherlands only later to be deported to Auschwitz with her husband and small daughter where they all perished. Heinz's mother would pass away of natural causes in 1939, but his father, aunt, uncle, and cousin Ruth would be sent to Freiburg and from there to the Gurs internment camp as part of Operation Wagner-Bürckel.Footnote 39 Hermann Bähr died of pneumonia at Gurs in January 1941, although Heinz would be able to rescue the other three by arranging and paying for their release and immigration to the United States.Footnote 40

Heinz Bähr's trip back home in 1937 and the photos he would take are thus some of the last photographic sources of Breisach's Jewish community before its tragic end. In the second half of this article, I will analyse several of the photographs that he took and how they functioned as statements of self-representation and commemoration, resistance and responsibility-taking. We will note how elderly Jewish members of the community, who served as the majority of the subjects of the photos in this collection, participated in the creation of these visual and commemorative acts. To these ends, I will focus most of my analysis on the two types of photos that we find in the series of images that Bähr took in Breisach, namely portraits of elderly members of the Breisach Jewish community and photographs of community members in front of and inside the synagogue on a Saturday morning.

Bähr's portraits are not simple snapshots of fleeting moments but portraits that as such imply cooperation between the photographer and the photographed subject. Moreover, by their very nature, these portraits represent consciously constructed statements informed by conventions that were inherited from the long tradition of hand-painted portraiture and that had already been adopted by portrait photographers in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 41 By that time, portrait photography had become commonly employed to mark important events and/or to create portable mementos that could be given to loved ones as tokens of affection.Footnote 42 To be sure, Bähr's portraits are not typical honorific portraits where the subject is elevated and looks into the distance in such a way as to suggest ‘a sense of purpose and destiny’.Footnote 43 Instead, the portraits are taken from a relatively close distance, with the viewfinder placing the viewer on the same level as the photographed subjects, lending a clear sense of both proximity and intimacy. Moreover, the subjects (Figures 1 and 2) do not look away from the camera in an act of contemplation, but instead return the photographer's gaze and thus seemingly look at the viewer of the photograph, creating a sense of connection between the two. The effect is clear. By virtue of the proximity of the viewer to the subject, the images appear to create or reinforce a relationship, elicit empathy on the part of the viewer, and even suggest a sense of (mutual) responsibility. To be sure, this sense of responsibility was not theoretical or metaphorical. As noted above, Bähr would struggle very hard and ultimately succeeded in rescuing several members of his family.Footnote 44 We can, nonetheless, add that Bähr's sense of responsibility seems to have extended to include responsibility for his family and community's legacy, a responsibility that he shared with those who posed for the portraits and thus participated in the co-constitution of communal and family memory. What is particularly striking about Bähr's collection of portraits is the relatively advanced age of those who sat for him. Indeed, here we do not find a single portrait of someone who appears to be under fifty; his mother, Talie, seen in one portrait (Figure 3), seems to be one of the youngest individuals photographed; she celebrated her fiftieth birthday that very year. To be sure, as Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer have noted, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum works according to its own, very specific logic in determining which objects, images, and artefacts it accepts into its collection, and which ones it does not.Footnote 45 There is thus a good chance that other photos from this visit exist and that this selection of photos was donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum precisely because so many of those depicted would die shortly thereafter – in a couple of cases the individuals died of natural causes, while others would be deported and murdered. At the same time, the age of those depicted in Bähr's photos also appears to give visual confirmation of the demographic realities of German Jewry by the late 1930s, which I explored above.

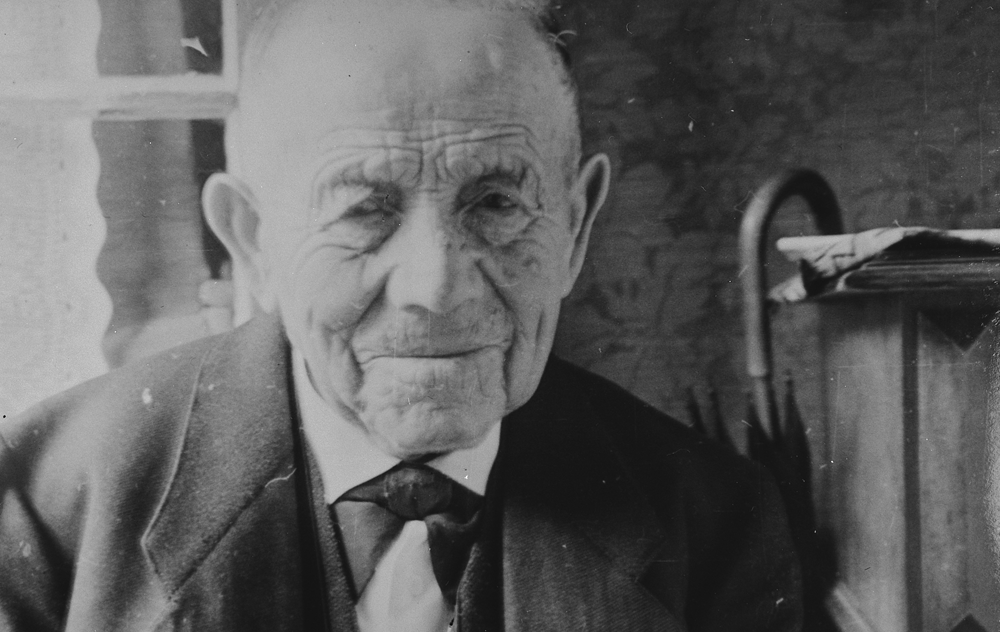

Figure 1. Close-up portrait of a Jewish man in Breisach, Germany (portrait of an elderly man identified as Leopold Geismar, a cousin of the Bähr family, who died in the Jewish Home for the Elderly in Gailingen in July 1939). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives # 69544. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

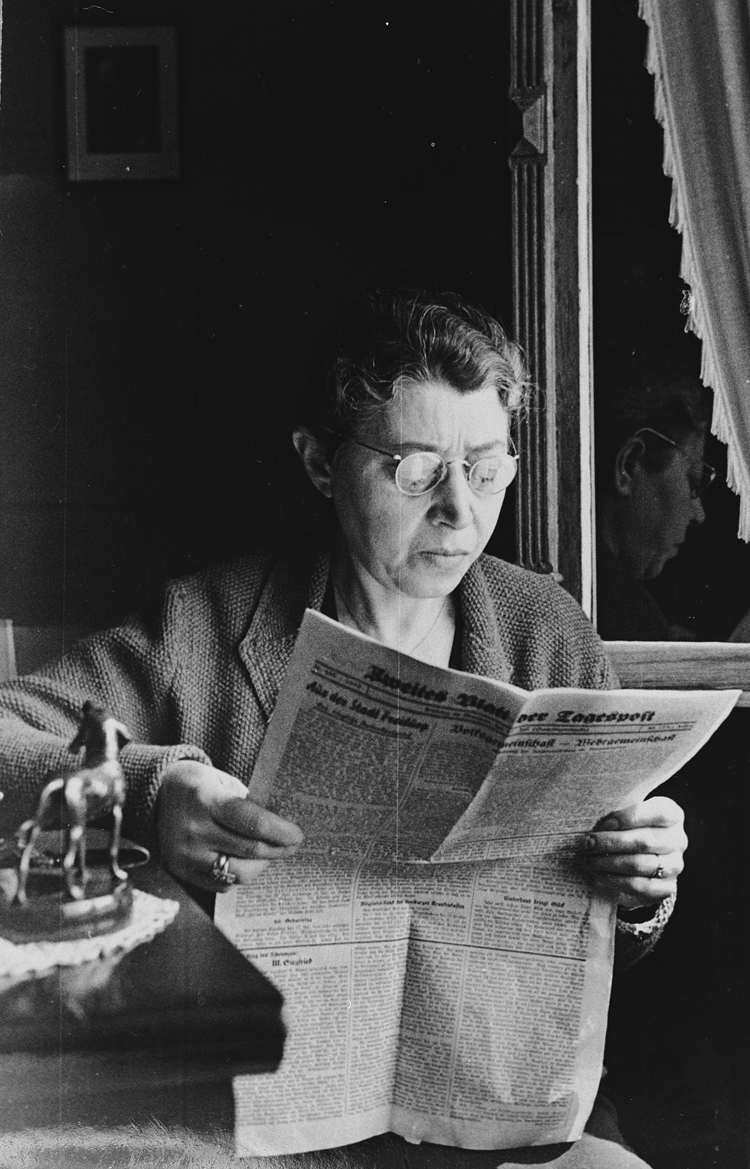

Figure 2. Close-up portrait of a Jewish woman in Breisach, Germany (portrait of Rosa Geismar, née Uffenheimer, born on 31 August 1879, in Breisach). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #69539. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Figure 3. A German-Jewish woman sits in her home and reads the newspaper (Talie Bähr, indoors, reading a newspaper, Breisach, 1937). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #69566. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Instead of statistics, however, Bähr's portraits literally give faces (and names) to the elderly.

Figure 1 is a portrait of an elderly man identified as Leopold Geismar, a relative of the Bähr family.Footnote 46 The man, dressed in a three-piece suit and tie, looks calmly and directly into the camera. His mouth is closed, and there is only a hint of a smile on his lips. A window is open, allowing the sunlight in, suggesting but not showing the town and world outside. Only a few further details are visible, including a fine white curtain and an umbrella hanging off a piece of wooden furniture, seemingly at the ready. The simplicity of the surroundings only further centres our attention on his face, which is set in the centre of the frame and absorbs our attention. Yet, unlike a passport photo, which also focuses on the sitter and their face, this image appears to seek to capture more than simply the biometric features of the man. Instead, it endows him with respect but also situates him in a domestic setting.

In contrast, taken outside in what appears to be a garden (though not necessarily a well-tended one), Bähr's portrait of Rosa Geismar (Figure 2) shows the fifty-eight-year-old posing at a slight angle.Footnote 47 Her head is turned to the camera, though she looks directly at the photographer. Like Leopold Geismar above, she is well dressed in clothing she might or could have worn on Shabbat. Her white hair appears to blend into the white wall behind her just as her black dress seems to blend into the dark foliage behind her. This staging seems to lend the effect that she is part of the physical environment around her, no less stable than the building behind her and no less rooted in, even perhaps an organic part of, the landscape and town. This visual instantiation of rootedness, while a common feature in German-Jewish photography during this period, done frequently to resist National Socialist claims to the supposedly inauthentic claim of Jews to the German Heimat,Footnote 48 also seems to suggest her immovability. While younger members of the community would and could move, like the plants and the building behind her Rosa appears not only to be a fixture in the landscape but fixed down to it.

While different in location and subject, in both photographs there is no external reference point, no clear indication of where the photo was taken; the emphasis is entirely on the person. The two individuals look directly into the camera. They are nicely dressed, serious and intent on being seen, but their lips are closed and they appear inactive. The images present aging witnesses. Through the direct and close-up angle, the focus on their eyes and the sympathetic framing, they are granted a degree of personhood and are not simply presented as demographic statistics. The gaze between subject and photographer to which the viewer is privy points to an attempt at co-constituting their memory, recording an authenticating image. However, while the photographs depict the individuals empathetically, they also appear to present them almost as emblems, even fixtures, of the town. Leopold Geismar is rooted in a domestic setting, blending into the furniture, just as Rosa Geismar seems to merge with the garden and building behind her. Even if Heinz Bähr hoped to help them leave Breisach, as he would other relatives, their rootedness highlights the challenges this would involve.

The staging and presentation of the two aforementioned portraits are noticeably different from Heinz Bähr's portrait of his mother (Figure 3), Talie Bähr, who is shown reading. She seemingly ignores the camera and instead focuses her attention on a local newspaper. The trope of reading has a long history in German literature and photography, and typically implies contemplation and Bildung.Footnote 49 However, by posing with a regional newspaper (here, the Freiburger Tagespost), and not a work of literature, the emphasis on the act of reading becomes a statement of concern for contemporary and, in this case, local issues. It further suggests a desire to remain informed, and participate even obliquely in local events, and expresses a desire for agency through this. Her portrait is doubled thanks to her reflection in the open window, giving a multidimensional view of her.

When compared with one another, the first two portraits (Figures 1 and 2) suggest participation in the documentation of the town and its people – the creation of a usable past – while the last image (Figure 3) points to a desire to remain in the present and perhaps plan for the future. Rosa and Leopold Geismar's portraits thus appear to show what we might expect: empathetic photographs of elderly residents whom Bähr was about to be leave behind.

Bähr's collection, however, also includes six photos taken outside the synagogue in Breisach, and an additional four taken inside – three showing community members participating in Saturday morning services. In addition to the photos taken by Bähr in 1937, there is yet another photograph taken outside the synagogue on a Saturday morning; it clearly was taken a number of years before Heinz's visit in 1937.Footnote 50 Its presence in the collection, by virtue of its earlier date, seems incongruent and requires explanation. Identified in Bähr's collection as having been taken between 1918 and 1933, the photo shows a group of individuals who are standing some distance from the photographer on what is labelled the Judengasse. All appear well-dressed, showing a prosperous and upstanding community. Everyone seems to be occupied, either walking or standing in small groups and engaged in conversation; only one or two people look towards the camera and thereby seem to acknowledge the presence of the photographer.

The photo is captioned as having been taken on Shabbat, suggesting that the community was willing to accommodate a transgression of Jewish law.Footnote 51 We might ask why. As mentioned before, already by the 1910s and certainly by the 1920s, provincial Jewish communities were well aware that they had entered their own twilight years with urbanisation increasing in pace. To be sure, many Jewish communities across Europe already by the tail end of the nineteenth century had begun collecting ethnographic material, especially from provincial and rural Jewish communities, in response to the dramatic changes that they witnessed and with the knowledge that unless they acted quickly, the last traces of their existence would be lost to posterity.Footnote 52 In this context, it is conceivable that the photograph was taken at a time when those present hoped to memorialise the community and its accomplishments (reflected in the elegant dress of all those present), just as they would have been cognisant that the rate of urbanisation would lead to its eventual decline.

On the surface, the presence of this particular photo in Bähr's collection seems to serve as a document of the longer history of the community to which he belonged. The image, however, reveals further nuances upon further inspection. Reproduced in other collections, the photo was shared by members of the Jewish community of Breisach. In two cases, the photo is credited to the collection of David Hans Blum, who was nine years younger than Bähr and also from Breisach, but apparently not a relative of Bähr.Footnote 53 The presence of this photo in Bähr's collection reminds us of the material quality of photography, as photos were shared by individuals and could serve as portable keepsakes, even many decades later. Yet, more critically, the photograph and its presence in Bähr's collection speaks to a longer process in which Jewish residents of Breisach memorialised the Jewish community and sought to create portable lieux de mémoire.Footnote 54

For Heinz Bähr, there are also a number of family connections represented in and through this photo. First, the image includes at least one member of Heinz's extended family: Rosa (Rosalie) Geismar née Uffenheimer, who is identified as standing third from the right and whose portrait we discussed above (Figure 2).Footnote 55 Thanks to the historian and archivist Uwe Fahrer, we also know that this photo was in fact taken some time before 1925 by Jakob Greilsamer, who was married to Auguste Greilsamer née Bähr.Footnote 56 Greilsamer took other photos of the Judengasse in Breisach in the early 1920s and it is conceivable, given these family and community ties, that Heinz Bähr was actively or tacitly encouraged to record family members, neighbours and the Jewish community during his visit, just as at least one family member had done years before. These family connections also suggest yet more opportunities for this specific photo to have made its way from one family member to another and into Heinz Bähr's possession. Critically, this photo gains importance for Bähr and his collection because it appears to serve, wittingly or not, as a prototype for Bähr personally and for the community more broadly to employ photography in order to create historical artifacts in the form of photographic mementos. Taken together, the presence of this photograph among Bähr's collection suggests a degree of active involvement behind the camera on the part of at least some of the older members of the community who we see also participate in front of the camera in Heinz Bähr's portraits.

Importantly, Bähr's own photos of the Jewish community on Saturday morning seem to reproduce the same general constellation we see in the earlier photo. Yet, the effect is tellingly different. Bähr's collection includes two photographs taken on the old Judengasse in front of the synagogue (Figures 4 and 5). In the first, we see more than fifteen individuals standing outside the synagogue.

Figure 4. German Jews congregate on the street outside the synagogue in Breisach after Saturday morning services (taken in the early 1920s by Jakob Greilsamer). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #69570. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Figure 5. German Jews congregate on the street outside the synagogue in Breisach following Saturday morning services. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #69569. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

In Figure 5, Fanny Bähr, Heinz's aunt, can be seen at the centre of the photograph wearing a white feather in her hat, standing to the right of the woman with a white hat. A young girl crosses in front of the group, lending a sense of movement to the image. She does not look at the photographer but turns her head away from him. In contrast, almost everyone else is looking at Bähr. This is very different from the earlier photo (Figure 4) where few sought out the gaze of the photographer or looked at the camera. Instead, in Bähr's image, those standing outside the synagogue appear to purposefully pose for the photo, as if to make sure that they could be seen and identified. We can also note that most of those photographed in this picture appear to be middle-aged, at the least, while certain other individuals, including the man to the far left wearing a hat and carrying a cane, are obviously much older (he is identified in another photo as Ferdinand Geismar, a cousin of the Bährs).Footnote 57 The contrast between the young and the old echoes contemporary intergenerational tensions within the Jewish community. It appears that in this ostensibly incidental image, Bähr's insider–outsider gaze on the community has captured a fundamental aspect of provincial Jewish life, which has been otherwise unarticulated.

In the second image (Figure 6), the young girl is seemingly replaced by an elderly, somewhat bent-over man who stands to the centre-right and captures our attention through a combination of his posture, his direct gaze at the camera and the lighter colour of his suit. He, too, is the subject of another photo taken outside the synagogue and is there identified as Leopold Geismar, who was roughly ninety-four years of age at the time.Footnote 58 Behind him, to his left and thus to the viewer's right, there is a young man in short trousers, one of the few individuals below middle age visible in the photo.

Figure 6. German Jews leave the synagogue on Judengasse at the end of Sabbath morning services. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #69563. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

On a simple demographic-documentary level, Figure 6 confirms the statistical realities of German Jewry in the late 1930s by highlighting the relatively advanced age of the community (some individuals appear to be middle-aged, but most are older). The lack of mobility in this photo seems to add a sense of rootedness, certainly when compared to the previous image. Whereas Figure 5 depicts a young girl in motion, here the older members of the community are strikingly fixed, concentrating on looking back at Bähr, the photographer. What is particularly noticeable, especially in comparison to the photo taken more than a decade before (see Figure 4), is that most individuals appear to make eye contact with the photographer and several clearly smile in his direction. To be sure, smiling for the camera had become such a simple reaction that it would have been an almost automatic response for many of those who saw Bähr with his camera in hand. Yet, enough photographic collections by German Jews during the National Socialist era demonstrate the frequency by which seemingly normal routines were used as defiant displays of private happiness in the face of worsening conditions in the public sphere.Footnote 59 If we assume that the objective of both photos – the one taken before 1925 and those taken by Bähr in 1937 – was to document the ‘normal’ routines of the community, then the effect of normality was achieved in the earlier photo by looking away from the camera and focusing instead on displaying authenticity by acting as if no camera were present. In Bähr's photos, in contrast, normality is achieved by acting out daily routines in conjunction with established conventions of photography, including posing and smiling for the camera.

Moreover, the insistence on presenting as normal a picture of life as possible was also reflected in the community's desire to record and commemorate its continuing celebration of Jewish religious rituals and services. To these ends, Heinz Bähr was given permission to take photos inside the synagogue during shabbat services. Here, though, we see a clear tension between the desire to display normality with the obvious fact that very little about Jewish life during the late 1930s was normal anymore. Thus, while they aimed to show continuity in their routines, despite everything that was happening around them, they sought to document their lives and their community precisely because of the dramatic changes that the community faced. This tension also goes some lengths toward explaining the desire of those in the photos outside the synagogue to look to the camera and have their presence and faces recorded.

The desire to commemorate the community, and the individuals who composed it, is reinforced by the fact that only one of these images shows a room without people (namely, a photo of the small chapel in the synagogue).Footnote 60 The other three focus not simply on the synagogue as a location and its ritual objects, but on people in the process of using that space, thereby making the synagogue a site of living and lived ritual. As we will see, the series of photographs taken inside the synagogue during the Torah reading on Saturday morning uses this key moment in the Shabbat morning service to demonstrate the community members’ collective desire to express pride in their synagogue and their tenacity in maintaining Jewish practice and, no less importantly, to do so in style (i.e., in their fine Shabbat clothing).

The first of these three photographs (Figure 7) is taken from somewhere either in the middle or back of the synagogue, giving a somewhat panoramic view of the beautifully decorated synagogue. We can see men seated at prayer, though they are only visible from behind. A portion of the women's gallery is visible at the top left-hand side of the photo. The focal point of the photo is the front wall of the synagogue, where we can see the elaborately decorated ark and the raised bimah next to which, on both sides, stand two large menorahs. On the bimah stand three well-dressed men with fine black top hats; one is reading from a Torah scroll. In the second photo, Heinz Bähr has moved closer to the front of the synagogue and is taking the photo from a seated or standing position amongst the seated men. Yet, the overall scene is similar to that in the first (Figure 7): the camera again focuses on the bimah where the cantor, Michael Eisemann, although his face is entirely blurred, is clearly reading from the open Torah scroll in front of him. He is again flanked on both sides by men, possibly the same seen in the first photo. There are two additional men seen seated on the benches in front of Bähr, apparently reading along with the cantor's chanting of the weekly Torah portion; both appear to be middle-aged or older.

Figure 7. German Jews gather for Sabbath morning prayers in the synagogue in Breisach. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #69550. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The third and final image from this series (Figure 8) seems to continue Bähr's gaze from where he sat or stood when he took the second photo. Men are seated and prayer books are spread out in front of them. This time, however, instead of focusing on the bimah, which is just to the right of where this particular photo ends, the viewer's gaze is quickly drawn to a black plaque on the wall thanks to the contrasting colours and the plaque's central place in the photo. Though somewhat blurry, the plaque is legible as a memorial dedicated to those who had fallen ‘as heroes for the Fatherland’ during the First World War. Here again, we find an instantiation of a double act of commemoration: first in the form of the plaque itself, and then secondly through the photograph of the plaque. If the first two photos in this series were clear indications of the community's desire to enact and remember its commitment to celebrating ritual life in its historic synagogue, the third adds yet another layer: spiritual resistance is joined here with a defiant reminder of German Jews’ sense of duty and willingness to serve and die for their fatherland. The images together forcefully convey a strong claim to a rooted German-Jewish identity that saw Jewish religious life and German patriotism as being wholly compatible.Footnote 61 The image conveys a sober commitment to remember these sacrifices in a personal and communal way. Many of the families who had lived for generations in Breisach had also seen family members serve and, in some cases, as the plaque attests, die in the Great War. The family name Geismar, again cousins of the Bährs, is visible among the list of those fallen, suggesting that the plaque commemorated Bähr's own extended family's story of loss. Just as many German Jews would photograph family businesses, homes and even graves before leaving, photographing this plaque reinforced a duality between continuity and commemoration, an important component of the act of leave-taking and farewell.Footnote 62 Nevertheless, it is not impossible that this image was taken to highlight a bitter irony and not simply to commemorate past sacrifice and dedication: as the last members of the Jewish community recorded for posterity how they had come together and prayed, the focus on an emblem of a country and society that no longer existed only further reinforced the disintegration of all that they had known.

Figure 8. German Jews gather for Sabbath morning prayers in the synagogue in Breisach. (German-Jewish men seated during prayer services in the synagogue in Breisach. In the background, on the wall, is a plaque commemorating the fallen community members who died ‘as heroes of the Fatherland’ during the First World War.) United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #69551. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Conclusion

Heinz Bähr's small collection of photographs presents a collective portrait of a small provincial Jewish community on what we now know was the eve of its untimely demise. Only slightly more than a year later, the synagogue would be destroyed and roughly thirty men were arrested and sent to Dachau. Yet, this story of persecution, destruction and death is not, and could not have been, reflected in the photos. Instead, both as individuals and as a community, those photographed in Bähr's pictures act as witnesses to not only or simply a provincial Jewish community in decline (a process that had started long before the National Socialist takeover) but, more importantly, to a living Jewish community. Bähr's photos in and outside the local synagogue on a Saturday morning show the community as its members actively and proudly make their way to the synagogue and participate in the Torah service. From this perspective, we can and should understand these images as acts of spiritual resistance. The photos, especially those taken outside, also seem to re-enact an earlier moment in time when the community had sought to capture its legacy in photographic form. This double act of continuity and commemoration is repeated in the synagogue as Bähr photographed a plaque dedicated to the fallen heroes of the Jewish community of Breisach, whose deaths were commemorated first through the plaque itself and then again in Bähr's photograph of it. The repetitive nature of commemoration reflects a historic consciousness of the community and its members, an awareness of the significance of the times in which they had lived and the dramatic changes they witnessed.

Moreover, the layers of commemoration give added meaning to Bähr's portraits. Their apparent lack of agency is overturned as we consider the multigenerational co-constitution of photographic lieux de mémoire. From possibly sharing earlier photos to participating in the images themselves, these same, mostly elderly individuals agreed to the recording of religious services for posterity and often readily sought out the camera's gaze both in order to mark their participation in Jewish communal life and as they posed at home and in gardens around the town. Photography is, by definition, a silent medium and there are limits to what can be said or conveyed in a given image. Yet, the photographs nonetheless reflect the intent of the elderly of the community to be seen and remembered, just as they point to Heinz Bähr's desire to authenticate their presence and record a lost German-Jewish way of life. In this sense, Bähr's photos record a relationship and a desire to take responsibility for those he photographed, if not always for their physical safety – an almost impossible task, though one he would nonetheless carry out in several instances – but for their legacy. His images ask the viewer to bear witness to the personhood, dignity and humanity of those photographed, to recognise them as proud Jews who maintained their heritage and were rooted and grounded in the town of their forefathers and foremothers.

Acknowledgements

My deepest thanks to Prof. Ofer Ashkenazi (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) for many insightful comments on an earlier version of this article and for his continued support. I would also like to thank Dr. Uwe Fahrer for his kind assistance in helping me uncover vital information about Figure 2 and the context in which it was taken. Research for this article was made possible by grants from the Israel Science Fund (grant no. 499/16) and the German-Israel Foundation for Scientific Research (grant no. I-107-111.5-2017).